PENNSYLVANIA...COVER: Photos of a guy in the dough stirring up favorite carp dough-ball receipes....

Transcript of PENNSYLVANIA...COVER: Photos of a guy in the dough stirring up favorite carp dough-ball receipes....

Photo by '•

IF Y O U DID THIS

You are ruining outdoor Pennsylvania!

Keep Pennsylvania Green

Keep Pennsylvania Clean

Don't be a litterbug!

COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA

H O N . GEORGE M . LEADER GOVERNOR

P E N N S Y L V A N I A FISH C O M M I S S I O N

R. STANLEY S M I T H , Pres ident WAYNESBURG

ALBERT R. HINKLE, V i c e - P r e s i d e n t CLEARFIELD

WALLACE DEAN MEADVILLE

GERARD A D A M S HAWLEY

CHARLES C. HOUSER ALLENTOWN

J O H N W . GRENOBLE NEW BLOOMF1ELD

EXECUTIVE OFFICE

Execut ive Di rector (Vacant)

H. R. STACKHOUSE Administrative Secretary

R. C. McCASLIN Comptroller

C O N S E R V A T I O N — E D U C A T I O N D I V I S I O N

J . ALLEN BARRETT Chief

FISH CULTURE

C. R. BULLER Chief Fish Culturist

GORDON L. TREMBLEY Chief Aquatic Biologist ARTHUR D. BRADFORD

Pathologist CYRIL G. REGAN

Chief Div. of Land and Water Acquisition GEORGE H. GORDON

Chief Photographer THOMAS F. O'HARA Construction Engineer

HATCHERY SUPERINTENDENTS Dewey Sorenson—Beliefonte Merrill Lillie—Corry & Union City Edwin H. Hahn—Erie T. J. Dingle—Huntsdale Howard Fox—Linesville J. L. Zettle— Pleasant Mount George Magargel—Reynoldsdale Bernard Gill—Tionesta John J. Wopart—Torresdale

ENFORCEMENT W. W. BRITTON

Chief Enforcement Officer

DISTRICT SUPERVISORS Northwest Division

CARLYLE S. SHELDON Conneautville, Pa.; Phone 3033

Southwest Division MINTER C. JONES

3«l W. Lincoln St., Somerset, Pa.: Phone 5324

North Central Division C. W. SHEARER

200 Agnew St., Mill Hall, Pa.; Phone 375

South Central Division HAROLD CORBIN

521 13th St., Huntingdon, Pa.; Phone 1202 Northeast Division

RALPH O. SINGER Tafton, Pike Co., Pa.;

Phone Hawley 3409 Southeast Division JOHN S. OGDEN

242 E. College Ave., York, Pa.; Phone 7434

P E N N S Y L V A N I A ANGLER

VOL. 2 4 , No . 8 AUGUST, 1 9 5 5

IX THIS ISSUE

THE T E M P E R A M E N T A L Y O U G H I O G H E N Y W i l b e r t N . Savage 2

EARLY A M E R I C A N S P O R T I N G M A G A Z I N E S Chas. M . Wetze l 6

C A R P — C H A M P O F T H E H E A V Y W E I G H T S M a t t Thomas 8

C A R P C O O K I N G J . Almus Russell 10

TICKS, U N W E L C O M E H I T C H H I K E R S G . Herndon Schneider (2

PICKEREL PACK P O W E R O N L I G H T T A C K L E Ray Ovington 14

SAFETY FIRST A F L O A T Don Shiner 16

C O M P A R A T I V E BASS F I S H I N G Richard Alden Knight 19

DEER, C A R I B O U , POLAR BEAR FOR BASS BUGS John F. Clark 20

MEET T H E N E W FISH C O M M I S S I O N E R 22

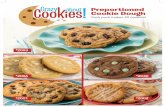

C O V E R : Photos of a guy in the dough stirring up favorite carp dough-ball receipes. Typical angler messes up Mom's po+s and pans, stinks up the kitchen, loads up the sink and takes off to tangle with a carp. See story on page 8.

Photos by Don Shiner

BACK C O V E R : Lake Wal lenpaupack, choice fishing, camping, boating, picnicking area, popular as a top Pennsylvania vacation spot.

George W. Forrest, Editor 1339 East Philadelphia Street, York, Pa.

The PENNSYLVANIA ANGLER Is published monthly by the Pennsylvania Pish Commission, South Office Building, Harrisburg, Pa. Subscription: $1.00 per year, 10 cents per single copy. Send check or money order payable to Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. DO NOT SEND STAMPS. Individuals sending cash do so at their own risk. Change of address should reach us promptly. Furnish both old and new addresses. Entered as Second Class matter at the Post Office, Harrisburg, Pa., under Act of March 3, 1873.

Neither Publisher nor Editor will assume responsibility for unsolicited manuscripts or illustrations while in their possession or in transit. Permission to reprint will be given provided we receive marked copies and credit Is given material or Illustrations. Only communications pertaining to manuscripts, material or Illustrations should be addressed to the Editor at the above address.

T he temperamental youghiogheny

IN AND OUT RIVER is the Youghiogheny winding thru three states. This sign, at Weber's Crossing is on Route 219 , identifies the Maryland branch. To the southwest the other fork

winds its way out of West Virginia.

THE NARROWS is visible here looking down river above Broad Ford. If you cannot pronounce "Youghiogheny" simply grunt "Yough".

PROBABLY very few of the many individuals who daily witness the Youghiogheny's quiet flow

into the Monongahela's more celebrated waters ever

pause to wonder where the Youghiogheny has its beginning; where it ranks in regional historical significance; what kind of countryside it mirrors throughout its headlong northerly course; how >' came to bear the name "Youghiogheny," etc. Yet this does not mean that the river, and the land through which it finds a sinuous passage are not worthy of classified entry-identity with our more widely acclaimed watercourses.

Far on the southerly side of the Mason and Dixon s Line the Youghiogheny manages a small beginning in two crooked-as-a-dog's-hind-leg forks—one in Maryland; the other in West Virginia's Preston County-The Maryland headwaters branch squirms well beyond Oakland, countyseat of Garrett County, running almost with stagnant quietness in glade-lands peppered with cattails and rank swamp grasses. An upstream trek from Weber's Crossing (on Route 219 two miles east of Oakland) would immediately bring you to a point where a lithe school boy could easily leap across the stream's normal width. Follow the writhing, shrinking stream a few more miles and pause to carefully study the earth's features ahead. It may surprise you to learn that you're almost within the frowning shadows of Backbone Mountain. From beneath this great upthrust hogback of earth and stone and windwhipped forestland trickle the icy-cold springs which form one arm of the infant Yough.

Out of the rugged fastness of Preston County the other fork tumbles from West Virginia's famed hills, crosses U. S. Route 50, and finds its way into Maryland near Crellin, a mining town which a score and a half years ago was credited with being the seat of an acid poison which killed enough fish, as one angler put it, "to build a fort if all the big ones would be

stacked up like hewn timbers . . ." Some people believed the poison came from mines in the region of Corinth, W. Va. Others were certain the evil killer was released by canneries putting up peas and corn, with cannery refuse going into the river. At any rate the deviltry was done, and in the end the mines

had to shoulder the blame; perhaps it was a combination of poisons which, together, became chemically much more lethal.

A short distance downstream from Oakland (A miles separate Crellin from Oakland) the two

2 PENNSYLVANIA ANGLER

By WILBERT NATHAN SAVAGE Photos by author & John T. Stagner

branches unite and the Youghiogheny is formed. An odd sidelight too amusing to omit is the parenthetical fact that officially the State Roads Department of both West Virginia and Maryland have bridge approach signs which read "Little Youghiogheny River." However, the West Virginia branch is known as the "Big Yough" to everybody in the area through which it flows. Only the Maryland headwaters branch is known as the "Little Yough" among regional native folk.

The length of the Youghiogheny is more than six score miles. It empties into the Monongahela at McKeesport at an elevation of less than 700 feet above sea level; yet its headwaters take shape in the foothills of a mountain range having an altitude of 3,320 feet! This, of course, is the aforementioned majestic Back-hone Mountain, which flings itself astride the Maryland-West Virginia border like a craggy rider straddling a steed. Little Wonder that the Yough flows with exciting swiftness at many Points, and has several exquisitely scenic waterfalls!

Thick laurel, catkin-clustered alders, and hardy willows line a great deal of the still-water-and-riffle stretches of the upper Yough. Ugly old water snakes, as big as they come, drape themselves on convenient shoreline flora; turtles and frogs sun themselves on partly submerged waterlogged timbers; and at night 'he fastidious muskrat, the stealthy mink, and the curious raccoon stamp their network of tracks in the soft water's-edge muck and sand. On a few feeder streams there are beaver colonies which, "i at least one instance, were reported to be increasing at a remarkable rate. Mankind, in the entire headwaters country, Populates the area sparsely. It is not uncommon for a tract of five thousand acres to contain not a single dwelling, save, perhaps, a rustic hunting lodge. For this is the land of the buck snd the doe and the alert wild gobbler. The entire population of Garrett County, Maryland, is less than that of the town of Connellsville, Pa. (Population 14,000); yet Garrett County is the largest county in the state of Maryland.

Although the Youghiogheny finds a significant position in tri-State history and in authentic tales of frontier adventure and military skirmishes, the resolute stream has known only minor ^cognition as a practical channel for navigation. If the river ever was uncertainly destined to see a flourishing day of water-borne traffic, man and the elements stepped in to oppose with determined and long lasting sinews of resistance. Specifically, man cleverly arranged railway opposition to any and all plans for extensive utilization of the river's cargo-carrying capacities; and Hoods of fierce proportions ripped out dams intended to form an early system- of slackwater transportation.

On February 9, 1850, I. E. Day, Engineer, submitted to the Commissioners of West Newton and Connellsville Navigation Company the results of a river survey started on November 3, 1849. From the head of the pool of Dam No. 2 on the Yough

BURNED AT THE STAKE by hostile redskins. Col. William Crawford under Gen. Washington's command, silently but steadfastly looks out over the Yough's waters, a region rich in history of America's struggles to build a nation. The statue is at

Connellsville.

(Please turn page)

AUGUST—1955 3

SCENIC, TREACHEROUS OHIOPYLE FALLS on the Youghiogheny at Ohiopyle. Rocks are slippery, river is up to 100 feet deep in spots. Victim of poor watershed practices years ago, the river floods easily,

destroys life and property.

MEASON HOUSE, home of Western Pennsylvania's first big-time ironmaster, Isaac Meason, • who operated furnaces on the Yough in early 1800's. His 20-room house^ built in 1802, is still in good condition and

occupied.

YOUGHIOGHENY RESERVOIR is fine picnic area ofie ' ;

boating, fishing, recreational facilities. The dam * " 248,800 acre-feet of water storage, is located '

Fayette and Somerset counties.

P E N N S Y L V A N I A A N G L E R

Navigation, at the borough of West Newton, the su r veying team bucked severe weather and completed their survey on November 22. The distance from their point of beginning to the Connellsville bridge was recorded as 25 and %ths miles, with a s tream drop of a little more than 122 feet.

Recommendations were made for nine dams and locks—six of UVz feet lift each; one of 14 feet lift and one of ten feet lift. Total cost of nine locks and nine dams was estimated at $211,805.10, representing a per mile cost of $8,347.00.

At the t ime of the survey the volume of the Youghiogheny was estimated to be more than 3,000 cubic feet per minute for normal-flow periods. The nine dams were planned to handle 36 boats a day. Rent to be paid by the vessels of commerce was set at $760.00 per annum.

A great deal of the planned work was carried out, but in 1865 disastrous floods seriously damaged the dams and from that time on they were permit ted to fall into a sorry state of moldering ruin. Even so, r iver transportat ion on the Yough did occur, with the mouth of Dunbar Creek above Connellsville usually being considered the head of navigation.

S. M. Berg, in a book devoted to Fayet te County history and na tura l resources, says: "Following the Revolutionary War period, Connellsville was one of the recognized flat boat building centers. Much later, from the Locomotive Works which stood on the west side of the river in the 1880's locomotives were floated down the river on flat boats . . . " (presumably at high-water periods) .

Salt works were located five miles up- r iver and produced about thir ty bushels of salt per day, most of which also was boated down the river to markets in the Pit tsburgh area. From 1843 until the early 1860's the Cochran Coal Interests of Dawson, Pa., m a n u factured coke and sent it down the Youghiogheny in flatboats to points on the Ohio River, to be used in the manufacturing business. Perhaps even then some shrewd thinkers knew that one day the Connellsville-Uniontown region would become the coke center of the world.

"From 1793 until 1827," Berg writes, "ferries were in operation in and around Connellsville. A ferry was operated near Lay ton (between Connellsville and West Newton) for many years, but was discontinued nearly a quarter of a century ago.

"At Somerfield, Somerset County, a substantial stone bridge 375 feet long was built across the Youghiogheny. It was completed in 1818. It connected the counties of Fayet te and Somerset on U. S. Route 40 . . . The bridge spanning the Yough at Ohiopyle, Pa., was built by Fayette County in 1854 . . . The first bridge across the Yough at Connellsville was a wooden structure, finished in 1800. A toll bridge from the day it was pu t into use, it had a short life, for it was carried away by floods in 1816. The second bridge, also a wooden structure, was built in 1818 and stood intact until 1827 when the span on the west

side fell as a heavily loaded wagon was passing over it. It was rebuilt at once, this also being a toll bridge. In 1831 a heavy ice gorge carried away most of the structure, which was rebuil t in 1832. In 1860 the entire bridge was swept away by floods . . . A sus pension bridge was built in 1862, but was replaced by a 606-foot five-span steel truss bridge in 1899 . . ."

The latter bridge is still in use, but was by-passed by a $2,500,000 modern mul t i -span on relocated Route 119, formally opened in November, 1953 when, in the midst of a colorful ceremony and lengthy parade a bottle of champagne was dropped on its massive 4-lane bosom from a low-flying aircraft. Other Yough bridges worthy of note: the steel truss bridge at Dawson, 775 feet long, built in 1883; and the railway bridge at Broadford, pu t into use in 1882. There's quite an old bridge (highway) at West Newton; and at Sang Run, Maryland, a bridge spanned the Yough long before the turn of the century. Heavy traffic has twice required replacement since 1921. Below Oakland an ancient span recently was replaced; and at Friendsville a modern span now serves where an old-time structure once creaked under unfair loads.

Today, much of the hillsides overlooking the Yough have been stripped of timber, bu t at one time some of the finest white pine ever rooted in American soil clothed the country of the upper Youghiogheny—particularly in the Piney Run region and the Muddy Creek flatlands. It is all gone now greedily snaked out by wheezing little engines on a narrow-gauge railway that completed its destructive mission more than thirty years ago. Many old fields now go down to meet the water 's edge. Cleared away and farmed at one time, they've been abandoned to the twining bittersweet, the wild grapevine, the bristling thorn and wild plum and s turdy crabapple.

In certain par ts of the river, fish are scarce; the death-knel l that took them from the stream many years ago has never completely stopped ringing: something mysteriously s tubborn has kept portions of the wate r from encouraging a full r e tu rn to the finny plentitude of bygone decades. Some of the most popular trout streams in the east empty into the Yough—Salt Rock Creek; Laurel Hill Creek; Hoye's Run; White Rock Creek, and others. The era of the modern auto has made these streams available to uncounted anglers. Very often, t rout with superb fighting prowess may be caught where a mountain s tream empties into t he Yough. Actually, there are sections of the river where carp and catfish and other finny tribefolk thrive, while minor stretches probably would fail to yield a mud-puppy or water turtle. This much, however, is encouraging and reassuring: the river is undergoing a slow transition toward a generally improved condition. Bass and other fish do well in the flood-control dam at Confluence. The time certainly is near a t hand when the r iver will be pure from headwaters labyrinths to its juncture with the Monongahela.

(Turn to -page 24)

AUGUST—1955 5

E airly american sporting magazines

DURING the 1700's the lot of the average American was one of hardship and privation. Basically, he

was a farmer whose struggle for an existence left little time for anything except hard work.

At that time the country was overrun with deep dark forests and swift flowing streams. Here and there, sometimes many miles apart, smoke could be seen curling upwards from the log cabin of some intrepid pioneer who had the temerity to start a clearing in the midst of this savage infested region. The country teemed with fish and game and while the capture of it afforded a certain amount of pleasure, yet the primary object of hunting and fishing was food rather than sport.

But around the close of the century a new era was

beginning to develop. The frontier was being pushed farther to the west and new settlers came pouring into the region. In a few short years clearings blossomed into prosperous farms. Pressure of work was lightening; the dread of Indians had ceased; and more time was now available for sports and the better things of life.

With the exception of The Sportsmen's Companion nothing of importance had as yet been written on the American sporting scene. However, in 1819 John S. Skinner of Baltimore published The American Farmer. The weekly was mainly devoted to farming and furnished informative material on how to select a good farm from the type of timber standing thereon; how to clear the ground and remove the stumps;

(i P E N N S Y L V A N I A A N G L E R

By CHAS. M. WETZEL

methods on brush burning utilizing the wood ashes for fertilizer; care of fruit trees and things of like Mature. In 1825 the magazine included The Sporting Olio the first sporting column to be published in the country. As viewed nowadays the sporting column left much to be desired but so favorably received that it tempted Skinner to enlarge its scope and publish a new magazine devoted exclusively to the subject.

In September 1829 the first monthly number of the •American. Turf Register and Sporting Magazine made its appearance. In the introduction Skinner made known its objectives:

" . . . But though an account of the performances of the American Turf and the pedigrees of thoroughbred horses will constitute the basis of the

work, it is designed also as a magazine of information on Veterinary subjects generally; and of various rural sports as Racing, Trotting Matches, Shooting, Hunting, Fishing, etc., together with original sketches of the natural history and habits of American game of all kinds; and hence the title, the American Turf Register and Sporting Magazine . . . "

The magazine today is one of the treasures of any sporting library. Complete runs (15 volumes 1829-1844) are seldom encountered and bring fancy prices when they appear at auction. The set at the Alfred B. Maclay sale (Parke-Bernet Galleries 1945) brought $1,150 but considerably higher prices have been recorded. And well it should, for this is the first sport-

(Turn to page 25)

AUGUST—1955 7

arp . . . champ of the heavyweights

RIGHT in your own backyard there's a rowdy roughneck fish which can tear up your tackle

and leave you mutter ing to yourself. Chances are, you've completely overlooked this walloping whopper. Most fishermen do—for the common carp is more cussed than caught.

As far as carp are concerned, that 's fine. They loll contentedly; they multiply by the millions, crowding our lakes and streams with an astonishing and oftentimes obnoxious abundance. But some day soon the tide will turn, and fishermen will take up tackle and go stalking these "river hogs" . . . for here is a "sport" fish which pulls no punches from start to finish in a fight.

Here and there, fishermen are beginning to wise up to what carp can do. In Des Moines, Iowa, a fisherman tied up traffic for two hours one day while a thousand spectators watched him work his way to victory over a twenty- two pounder hooked below a bridge right in the hear t of the city. Near Dayton, Ohio, there's a carp-fishing clan that concentrates on fishing the fast waters flowing from a flood-water sluice. With thirty feet of line dropped straight down into racing water, a fisherman cuts out a big chore for himself when he tangles with a fifteen-pound carp capable of running the heavy current at will. He has an afternoon of tussle ahead of him, and if he likes to eat carp, he has food enough to last for weeks.

Closed seasons for carp fishing are practically u n heard of, and most states allow taking carp by any method which will do no ha rm to their more-favored and less prolific game species. What more could a fish offer than the wit and bru te strength served up by these boisterous buglemouths? Yet to most fishermen they're a plague!

If plague they are, we plagued ourselves. They were imported to this country mainly because cai-p were highly favored as a food fish in Europe and still are.

Years ago carp lived only in Asia. There they graced the private fish ponds of the emperors to be harvested for the most festive occasions. Then Europeans transported them to their continent where they became choice fare on royal menus. In England, Izaak Walton, the sport fisherman's patron, picked carp as one of his favorite fish. "The carp is the queen of r ivers: a stately, good and very subtle fish," he wrote in his now classic Compleat Angler. "And my first direction is," h e continued, " that if you fish for carp, you must pu t on a very large measure of patience."

Carp fishing today is still a top-ranking sport in England and Europe . . . still demands the same "large measure of patience." It 's not scarcity which occasions the need for patience; it's the caution and cunning of the carp—the most difficult of all freshwater fish to catch, according to the British.

Carp fishermen in England and Europe go a t their sport with craftman's care and preparation. In fact, they make many of our best t rout fishermen appear to be superb blunderheads. They take careful account of the weather before going out. They never touch the bait with their bare hands, often scenting them with an aromatic such as anise to kill carp-scaring human odor. They wear rubber-soled shoes and may also wear heavy stockings over these, and they cover their faces—for they are certain a carp spooks quickly at the sight of a white face—with bee veils or daub them with mud. When they sight a school of carp, they creep along the bank on all fours, stalking the fish until they begin to feed.

Carp weighing more than ten pounds are classed as "big" in England, and when a fisherman chances upon that once-in-a-l ifet ime catch weighing twenty pounds or more, he promptly hies himself to a t ax i dermist to get his prize mounted for display over his fireplace or in his den or office. One Britisher said of the man who had caught the biggest carp ever landed in England, "He looked as if he had been in heaven and in hell and had nothing more to hope for from life."

Here in this country carp are much like the rabbits introduced to Australia. With few natura l enemies and little commercial marke t value or appeal to sport fishermen, carp soon spread unhindered throughout our natural waters. Many fishermen are convinced, in fact, that carp are entirely undesirable intruders— that they have pushed and evicted our game fish from their living quarters . But bielogists, who have studied the mat ter carefully, are less accusing. Carp, they say, inhabit waters often undesirable as habitats for many of our game fish. Carp can prosper, in spite of mud and pollution—in the "open sewer" streams and "cesspool" lakes which we have so ruthlessly provided.

Anxious farmers have scoured brush from their lands, cleaned out fence corners, planted soil-wrecking crops year after year—all to squeeze more and more income from every tillable square foot of land. And with each rain some of the farmers' topsoil has washed away. It has built up on the bottoms of streams and

(Turn to page 27)

P E N N S Y L V A N I A A N G L E R

By MATT THOMAS -Photos by Geo. H. Gordon, Chief Photographer,

Pennsylvania Fish Commission.

MIRROR CARP has scales in scattered patches on its body. Carp have been residents of Pennsylvania since 1879 when a number were brought from Washington, D. C. to the state fish hatchery at Donegal Springs near

Marietta, Pa.

\ 9ht

CA|j|, fully scaled, most commonly by Pennsylvania fishermen. In

!,. Rudolph Hessel brought 345 carp

% (;„' Germany for the United States _ Commission. First carp in Pennsyl-

Hg ° Were stocked largely in farm s' from where they spread into all

Parts of the Commonwealth.

AUGUST—1955

MOST people have a decided distaste for carp thru proxy. Though

they have never swished a bit of properly cooked carp around their palates, what they hear and what they read amount to heresy only. Gourmets with a yen for birds nest soup are considered idiosyncrats. Merely the mention of snails, rattlesnake steak or hog-brains is sufficient to overturn the best stomachs of those totally addicted to roast beef and mashed potatoes.

Many adults, much like children, must be queried . . . "how do you know you don't like it until you've tasted?" Now, before you put carp cookery in the category of lark's tongues or unicorn hoofs, go out, catch yourself a carp and try cooking it the right way. Only then can you give out with a rumor one way or the other.

Those who think they would object to the flavor of cooked carp should first soak the scaled, dressed, washed fish in strong salt water over night; then freshen the fish by putting it in cold water and bringing the water to a boil before removing it from the kettle. Now get to the recipes listed herein, pick out one that fits your kitchen utensils and spice or herb shelf, then proceed.

10

BOILED CARP (Modern Recipe,)

Temperature—boiling for Time—10-15 minutes

2 pounds carp 4 cups boiling water 1 tablespoon vinegar 2 teaspoons salt

Cut the dressed fish in large pieces, lay pieces on a plate, tie all in cheesecloth, and cover with boiling water to which the vinegar and salt have been added. Boil until the flesh leaves the bones. Remove to a hot serving plate and garnish with chopped chives.

BOILED CARP (Century-old Recipe)

Scale and clean a brace of carp, reserving the liver and the roe; take half a pint of vinegar, or a quart of sharp cider, add as much water as will cover the fish, a piece of horseradish, an onion cut into slices, a little salt, and a faggot of sweet herbs; boil the fish in this liquor, and make a sauce as follows: Strain some of the liquor the fish has been boiled in, and put to it the liver minced, a pint of Port Wine, two anchovies, two or three heads of shallots chopped, some salt and black pepper, a little Cayenne, a tablespoon-ful of Soy; boil and strain it, thicken with flour and butter, pour it over the carp hot; garnish with the roe fried, cut lemon, and parsley.

POACHED CARP WITH CURRY CREAM SAUCE

Temperature—simmer for Time—10-12 minutes

Carp fillets Boiling water Salt Lemon juice White wine

Place carp fillets in a shallow kettle, half cover with boiling water, season with salt and lemon juice, and add a dash of white wine. Cover kettle and

By J. ALMUS RUSSELL

simmer contents according to the thickness of the fish. Place the unbroken fillets on a hot platter and pour over them—

CURRY CREAM SAUCE 2 tablespoons butter 1 tablespoon minced onion 1 tablespoon flour

1% teaspoons curry powder 1 cup milk

Melt the butter. Add the minced onion and cook until tender. Stir in the flour mixed with the curry powder. Into this mixture pour the hot milk, cooking and stirring until the boiling point is reached. Strain before serving.

CARP SOUP 3 pounds carp, cut in chunks 2 quarts cold water 2 medium-sized onions, chopped 1 celery stalk, chopped

Salt Pepper

1 tablespoon minced parsley 1 cup milk 2 tablespoons diced salt pork

Fry the onion and celery with the salt pork. Combine with the other ingredients and seasonings. Simmer until the fish is ready to fall to pieces.

STEAMED CARP WITH WINE BROWN SAUCE

Clean, scale, and bone carp. Season with salt, pepper, and

paprika. Wrap fish in cheesecloth and steam

until flesh is tender. Remove from cheesecloth and place

on hot platter. Serve with—

Wine Brown Sauce 1 cup hot brown sauce (made with

fish stock) 1 cup red wine 1 tablespoon minced onion 1 small bunch savory herbs Saute the onion and herbs in butter. Then remove the onions and the

PENNSYLVANIA ANGLER

herbs, adding the but ter to the brown sauce. Heat mixture thoroughly and serve hot over the fish.

CARP CHOWDER Temperature—slow boil for

Time—40 minutes 2 pounds carp 1/3 pound salt pork 6 medium-sized potatoes 1 medium-sized can tomatoes 2 medium-sized onions, sliced 1 large sweet pepper, minced

salt, pepper, paprika Scale, skin, and clean the fish. Cut

in two- inch pieces. Cut pork in half-inch slices. Sprinkle a little pork in bottom of an iron kettle. Cover with a layer of fish, potatoes, tomatoes, and par t of Ihe onions and pepper. Season. Repeat the procedure unti l all of the ingredients are used. Cover with cold water and boil slowly as directed.

BROILED CARP

Cut the prepared fish into thick slices.

Season wi th salt and pepper. Cook on well-greased broiler from

10 to 20 minutes, turning slices to cook both sides evenly. Remove fish to hot platter, sprinkle with chopped parsley, and season with lemon juice.

STEWED CARP (Century~old Recipe)

Scale and clean a brace of carp, r e serving the liver and the roe; pour over the fish in a deep pan a pint of vinegar, which may be elder vinegar, if the flavor is preferred, with a little mace, th ree cloves, some salt and Jamaica pepper, two onions sliced, a

faggot of prasley, basil, thyme, and majoram; let them soak an hour, then put them in a stewpan with the v inegar, and other things, the liver chopped, a pint of Madeira, and th ree pints of veal stock; stew them an hour or two according to their size; take out the fish and p u t them over a pan of hot water to keep warm while the following sauce is made:

Strain the liquor, and add the yolks of th ree eggs beaten, half a p in t of cream, a large spoonful of flour, and a quar te r of a pound of butter, stir it constantly, and just before put t ing it over the carp, squeeze in the juice of a lemon. Boil or fry the roe.

FRIED CARP Scale and clean the fish. Split i t u p

the back, flattening the backbone. Sprinkle the fish on both sides with flour. Season with salt and pepper. F r y in a hot frying pan to a rich color, and serve wi th lemon juice.

SCALLOPED CARP WITH WHITE SAUCE

Temperature—350 deg. Fahr. for Time—30 minutes

2 cups cooked flaked carp 2 hardboiled eggs 2 cups whi te sauce 1 teaspoon salt Yi teaspoon pepper 1 cup but tered breadcrumbs

Chop eggs and add to the white sauce.

Arrange alternate layers of sauce and flaked fish in a greased baking dish. Cover with but tered breadcrumbs and bake as directed.

White Sauce

4 tablespoons but ter

4 tablespoons flour 1 teaspoon salt 2 cups milk

Melt fat in top of double boiler. Add flour and salt, s t i rr ing unti l

well blended. Add preheated milk slowly, stirring

constantly until a smooth paste is formed.

SAVORY FISH HASH

6 small link sausages 3 cups diced cooked potatoes 1 coarse chopped apple Yz teaspoon salt Ys teaspoon pepper 2 cups flaked cooked carp Juice of Yz lemon 1 boiled beet 1 tablespoon minced watercress

F r y sausages and drain. Pour off half of the fat. Mix the potato and apple in a frying pan, season wi th sal t and pepper, and stir unti l thoroughly heated. Then add the fish and cook slowly until browned, adding more fat if necessary. Place on a hot plat ter , sprinkle with lemon juice, and garnish with the sausages, sliced beet, and watercress.

PANFRIED CARP 2 small firm carp with heads and

tails left on. Sprinkle the scaled, cleaned fish with salt and pepper. Roll fish in cornmeal unti l lightly covered. F r y in hot frying pan in hissing hot fat. Brown well on both sides and serve hot.

{Turn to page 32)

AUGUST—1955 11

X ieks—unwelcome hitch-hikers

IMiata*,* ' ! * 1 J . ' , r v * v

TRANSFUSION TACTICS usually commence on neck at base of hairline, where, if not promptly discovered, tick gets free blood donation. Dreaded Rocky Mountain fever is transmitted to humans by the spotted-fever

tick, rare in this area.

BLOW-UP of tick in "flattened" stage ready to take on any host available as a blood donor. Body is now about 3 16-inches in

diameter, tick has eight legs.

GORGED FEMALE, in comparison to "flattened" stage, is now one-half to three-quarters of an inch in length and many times larger in

bulk. She will lay as many as 3,000 eggs.

13 PENNSYLVANIA ANGLER

By G. HERNDON SCHNEIDER (Photos by the author)

TICKS are creepy little characters we often find on us after being

outdoors. We pick or flick him off with an unpleasant feeling. There's a reason for this feeling of revulsion when you know he's there to make a meal off your blood, not fussy about what type it may be. Chances are you're not the victim he'd ra ther have, but if left u n disturbed or unnoticed until a suitable spot on your hide is found, he'll settle for a transfusion from you instead of from your dog or another animal he prefers.

The little fellow we call the "wood-tick" can really be one of several ticks which infest Pennsylvania. Most likely, the ones making contact with you

would be the Eastern dog-tick, or possibly the brown dog-tick, a ra ther r e cent importation from the southern states. The spotted-fever tick, known carrier of spotted fever, or Rocky Mountain fever, is not native to the state of Pennsylvania, bu t within r e cent years, several cases of this serious malady have occurred in the east. Our Eastern dog-tick can also be a carrier of this sometimes fatal disease, which can be transmitted from animal to man, and from mother tick to eggs and future off-spring.

As the average individual sees them, they're either the little flat leathery tick you pick up during excursions astream or afield; or the swollen,

EGG LAYING, over a ten-day to two week period is done by gorged female. These eggs hatched within

three weeks of deposit.

gorged tick you find on your dog in a spot not too easily scratched. From a scratching angle anyone who knows the tick fairly well finds they're made of pret ty tough material . To merely step on one in the stage they're picked up in the field is not enough to put him out of business or even discourage his appetite.

Ticks are not insects in the t rue sense of the word, since all insects have six legs in their adult stage. If you will take closer look at the tick you picked up you'll notice there are eight legs present. This count puts the tick in the same class with other Arachnids such as all our spiders and their near-relat ives, the scorpions, crawfish, crabs, and lobsters. However, in the young, or "nymph" stage, most ticks we meet spend a portion of their life as a six-legged baby.

To study the life history of our be t te r -known ticks in this region, we should begin with a fully gorged female ready to leave her host, pe r haps a dog allowed to run afield occasionally, or a warm-blooded animal the size of a rabbit or larger. After feeding the gorged adult will drop off its host and continue about the bus i ness of digesting its meal for possibly one to three or more weeks, after which time egg-laying will begin. The adult tick probably seeks some place of concealment for protection of the eggs, near the drop-off point, since they are ra ther sluggish when fully distended.

The eggs, some two or three thousand, are laid in a mass and when egg-laying is completed the eggs constitute a bulk approaching the size of the female when leaving her host. When hatching, the little creatures that emerge are not the eight-legged ticks we recognize as adults, but are known as "seed-ticks," and have but six legs. Very tiny, these little fellows scatter

(Turn to page 29)

AUGUST—1955 13

p iekerel pack power on light tackle

LABEL him grass pickerel, green pike, banded pickerel, chain pickeral, jack or just plain

pickerel, but tangle with him once on light tackle and you'll call him one of the scrappiest fish that swims. Someone has said that all things are relative and so it goes with Mr. Pick. He's a junior lightweight in comparison with his big brothers, the pike and musky, but when you reduce your tackle to his size, he packs a real wallop. Seldom running to more than seven or eight pounds of fightin' flesh, he'll give you many times what you asked for.

As the poor man's musky, he's everything his older brothers are, only in miniature. He's the scoundrel of his territory, a gangster among fishes and like the pike and musky, a devil who'll kill just for the fun of it. Savage, unpredictable and stubborn! Many are the times I've fished over water I have known to contain big pickerel and thrown everything in the book without results. He's a real killer to the ego when he clams up in his smug little way and you spend hours of fruitless casting without so much as a strike for your efforts. One thing is certain however, Mr. Pickerel serves as a dress rehearsal for the time when you'll tackle the pike and the musky. Yes, he'll offer a series of experiences that are bound to stand you in good stead when that great day comes.

He's as common as fleas on a dog. There are few

ponds and lakes in the forty-eight states where you won't find him a popular, solid citizen of the weed beds. Like the rabbit, he seems to thrive next door to civilization, openly defying fishing pressure, seldom putting a call in for re-inforcement from the hatchery and outlasting largemouth bass in semi-polluted waters or areas in a lake unsuitable for other game fish.

He's as pretty as he is ferocious, his tonal effects varying widely, depending largely on the general water depth and conditions. Sometimes he is dressed a very mild pastel green with darker brownish-olive chain markings. Other times he's garbed mostly in bronze-brown with distinct black chain links. The most common coloration, however, is dark to olive green on the back and sides, with jet black chains blending into a pale yellow and dissolving into a mother-of-pearl white. Both upper and lower gill plates and gill covers are scaled, making him readily distinguishable from the pike and musky, neither of which have scales on their gill covers.

If fly fishing is your choice, lure him with a flashy colored bucktail or streamer. Red and white, orange and black, black and white streamers sometimes trailing a pork rind take him readily. If you are fishing during hot summer days there is one rule to remember . . . put them down deep. When you are sure the fly is deep enough begin a very slow re-

U PENNSYLVANIA ANGLER

By RAY OVINGTON

trieve so the hooks will brush by the weed stems, then start twitching in short je rks .

Weedless hooks and lures are a must and one of the best is the lead and buektail j ig-type fly de veloped recently in Florida to imitate the small crabs the bonefish feed on. My first experience with the lure was while bonefishing with Don McCarthy at Walker Cay, Bahamas, and I had such overwhelming success with it there, I decided to t ry it back home as a crawfish imitation for pickerel and bass.

Jus t the other night it came through with flying colors. Bob and I had been out for the better par t of an hour and neither of us had had a strike save a few surface sucking nibbles from giant sunfish. I handed Bob one of the bonefish lures and snapped another on my own spinning line.

"This thing sure works well, gets down deep wi th out fouling up," was his first comment.

"Work it a little slower, Bob," I suggested. Don't be afraid of getting it caught just keep it bouncing on the bottom and see wha t happens."

A couple of casts later his reel drag let go in three short jagged pulls.

"Something's got it and it's no snag!" he yelled. It was a small fifteen inch pickerel and he had

taken the lure well down in his troat. We immediately opened him. up to see wha t he had been eating and found his gullet filled with crawfish. Evidently the

imitation looked very much like the real thing. In many sections a small spinner trailing a red

and white fly is ha rd to beat. I learned to use this combination in the Upper Michigan peninsula country and have since relied heavily on it for pickerel and other game fish. It is quite surprising tha t more angler's tackle boxes don't contain these. They were very popular many years ago and I can remember my Dad using them on pike and bass when all else failed.

Believe it or not, small popping bass bugs will also take pickerel, though their use is limited to calm waters where lush growth of trees, vines and brush come down to the water . Evidently, Mr. Pick's eyes are used to looking here for succulent moths, grasshoppers and other tasties well imitated by the bug. Accurate casts are the rule, so throw the bug right to the edge of the shore or windfall. Work well the holes between the clusters of lily pads and surface weed patches, for these are the hiding places of many a good chain snake.

If your rod is old reliable, the bait caster, work an underwater diving plug slowly any hour of the day, fishing the shallows and under old windfalls, overhanging rock ledges and anchored rowboats.

Sometimes the bigger the plug, the faster he a p pears, bearing out the old thesis: "Big lure . . . big fish." Red and white, green and white, orange, are

(Turn to page 29)

• B M t t |

AUGUST—1955 15

a afety

M i i ' M

A float

By DON SHINER (Illustrations by Author)

RECENT years have brought a great increase in t he number of boats

afloat on the lakes and inland wate r ways of Pennsylvania. Biggest pe r centage of those afloat are fishermen, taking full advantage of this flexible means to reach formerly inaccessible fishing spots. Boating adds new enjoyment to angling, but the thrill of gliding smoothly across placid water ways holds an immeasurable amount of outdoor fun, a fast growing form of recreation. With this steady increase in boating enthusiasm each year, it becomes increasingly necessary to p ro mote and exercise common sense afloat to insure boating safety.

First step aboard—Limit your load-Common sense afloat begins with the

first step aboard. Having arrived at a particular lake, fishermen a re naturally anxious to get started, to shove the boat from shore, glide to some likely cove and begin casting. Hurrying, safety rules are often forgotten with the result an accident may occur before the boat actually leaves

•J,Turn to page 18)

16

WRONG WAY to enter a boat loaded with tackle. Off-balance, stepping into a pitching boat may give

this angler a ducking.

RIGHT WAY is »° h f / w , the" '

QUICKEST WAY TO PARADISE is to smoke while filling the gas tank. One tiny spark can blow things around

a bit.

BUZZING A FISHER' jerks but it can t»e

fun of oth«' pai*

fk fish'ng

•II

K.

P E N N S Y L V A N I A A N G L E R

ii^Wi 9 e t i n t o b o a t ' DANDY WAY to load a motor. This guy has got to

go . . . right into the drink)

THAT'S RIGHT, Elmer, get into the boat, then hikf the motor from the wharf.

mmm, man/mm

sPort

Na s spoiling the

""t. °* room when

NUMBER OF SEATS in a boat doesn't mean you've got to fill 'em. Overloaded boats are easily swamped, one of the top reasons why many Pennsylvanians drown

each year.

OVERPOWERED is this boat with two many horses. Fit the motor to the boat and keep speed in hand to

avoid grief or sorrow later.

AUGUST—1955 17

the wharf. Climb aboard the craft sensibly. Assist others in entering the boat.

The number of seats in a particular boat certainly does not indicate its capacity! The seats are there to permit a variety of seating arrangements but not to be all occupied at the same time by husky individuals. The average boat, 12 to 15-feet in length, typical of those owned or hired by fishermen, seldom has a capacity exceeding three persons. And for balance, safety, speed and comfortable fishing, the load should be distributed evenly from side to side, from bow to stern. If the bow looms far out of the water, passengers should move to balance the load. Changing seats should be done only when absolutely necessary, once the boat gets underway and only then when the motor is slowed or stopped or the craft steadied by dipping the oars.

Carry life insurance

A life jacket for each child, a bouyant cushion for every adult in the boat is basic common sense afloat. The fisherman may know how to swim, but mishaps sometimes occur which cause the boat to capsize. In such emergencies a life preserver's value far exceeds

(Turn to page 30)

LAW REQUIRES l ights at night so i n stal l them according to the regulat ions. Copies of laws are issued w i th your motorboat license . . . read them careful ly and obey. They're wr i t t en fo r

your own specific protect ion.

LIFE JACKETS proper ly f i t ted for children is just plain common sense and precaut ion, removes much worry f rom operator of the boat. Law requires carry ing H'e

preservers for every occupant.

SIT DOWN in a boat! Standing up for any reason •*

dangerous and you ' re asking for serious t rouble and a dunking.

WRONG WAY to drop the anchor. Do your shot-put t ing somewhere else, drop the anchor quiet ly over the side for

better fishing.

IS PENNSYLVANIA ANGLER

€ omparative bass fishing

BY RICHARD ALDEN KNIGHT

DURING the months of May and June, I was in Florida, gathering

material for a series of magazine articles. While there, I fished for big, summer-run tarpoon — fish running from 75-200 pounds. The equipment I used was standard tournament tackle —nine foot six rod, single action reel, GAF flyline and fifteen pound leader. I managed to hook nineteen of these brutes and landed only one—a minnow by local standards scaling 48 pounds. I returned home with sore arms and a strained back, questioning the sanity of an individual foolish enough to wage the unequal struggle of man vs. tarpon.

It occurred to me on the way home what I had been doing for a good number of years. Here I was heading back for the opening day of bass fishing. When I went out, I would be using the same rod, line and reel I had used in Florida to tangle with fish many times larger. It all did not add up.

A smallmouth is perhaps one of the most determined fish which swims in fresh water. Even a small one—say a pound—will give you an argument on heavy tackle let alone light. But look at it realistically. What chance has a fish of one pound against a big flyrod, an eight pound leader and a well-set hook? Very little I'm afraid. He gets railroaded and there is little if anything he can do about it.

During trout season, when the water level fell and the hatches became infinitesimal, I lengthen my leader to 14 feet and dropped my leader diameters to 6x and smaller. When I hooked a one pound trout—by no means as tough a customer as a bass of equal weight—on this hair-fine outfit, I found there was as much skill and care required in landing him as there was in landing those big tarpon

in Florida. One mistake meant a lost fish.

I do most of my bass fishing in the North Branch of the Susquehanna between Towanda and Wyalusing. In this stretch of long pools and deep riffles are some truly monstrous bass. Each year, I manage to take one or two really nice fish on a top water bug. Here again, I also hook and seldom lose a large number of small bass. As a result, the success of each trip was not measured in the quality of the fishing but rather the number of LARGE fish caught. Came a day when the big fish weren't feeding and I would not derive as much enjoyment from it as others. This, somehow, did not seem right to me.

When I was a boy, in my very early teens, I used to fish with my Dad in the West Branch of the Delaware River near Deposit, New York. As my hand was not large enough and strong enough to handle a big bug rod, I used an eight foot trout rod and a streamer fly. I can think back now and remember how pleased I was with a fish of a pound or better. The fight a bass of this size can wage against tackle scaled in proportion is amazing.

This year, I decided to change my whole line of thinking on bass fishing. To be sure, I still enjoy using a bass bug and seeing an old buster sail into it. But here is what I did.

The North Branch, like any other river, has portions of its length which are easy to wade. These shallow riffles and fiats, often not over three feet in depth, provide a cafeteria of sorts for feeding fish. During periods of activity, bass cruise these spots hunting for their daily meals. Rigging up with a light rod, 2x nylon point, and two small streamers tied on No. 6 hooks, I combed the riffles and pockets all

day. By conservative estimate, I must have taken forty bass. Of this number, perhaps one-fourth of them were undersized, half of them were legal to a foot in length and the remainder made up as nice a mess of fish as I have ever taken. The biggest, a stocky eighteen incher, was taken in less than two feet of water at the base of a pebble bar. Two others, both nice fish, fell on the fly within twenty feet of me. In short, I had one whale of a good time.

Sure, I lost fish! I wouldn't enjoy a day on any stream if I didn't get busted up once in a while. I had five fish wrap me around rocks and snags before I could do much about it. A big bass on tackle such as I was using has very definite command of the situation for a while. It took me over twenty minutes to land the largest one. On regular bug equipment, I would have whipped him in less than ten. Sound like fun? Here's what to do.

Use any light trout rod, preferably eight feet in length so that you can handle a fair length of line easily. Balance this outfit with a reel containing at least fifty feet of backing and a line to fit the rod—probably an HDH. Your leader should be at least eight feet in length, preferably ten. Taper it down as light as possbile. Do not go any heavier than 2x if you really want to get the most out of your day.

To your leader, attach a pair of small streamers. The day described above, I was using a KNIGHTHAWK as the tail fly and a MICKEY FINN on the dropper. This combination worked very well for me. But there, is a matter of personal choice. Any reliable pattern will take fish. Just be sure that the hook size does not exceed No. 6. By

(Turn to page 32)

AUGUST—1955 19

D eer + caribou •+- polar bear = bass bugs

CERTAINLY it's an odd equation by any stretch of the mathematical

imagination but take 'em piece by piece or all together, they work. You can prove it by taking up scissors, s tar t snitzing away at an old deer hide. Then if you can keep your reason be fore starting off on a tangent to cut out paper dolls, you'll come up with a feat of barbering, a credit to the tonsorial arts. The final product is a bass bug, a cross between a song sparrow and a 'possum.

Now we don't want to get you started on these bugs if you do not intend to use them. For some strange reason, bass appear to like the taste of the dadgummed things. But then bass bite on many other assorted items such as pig hide which has no hair attached. Here, we go into reverse, we use the hair and throw the hide away. If you ' re confused just skip it and get out the vice . . . here we go.

Tying the deer hai r bug is fairly simple after you've practiced a little while. And you can tie them with a minimum of tools and materials.

Here is a run -down of the basic stuff you will need:

Fly tying vise

Heavy, waxed tying thread

Small scissors for t r imming

Fly head cement

An assortment of hooks (No. 1/0 to about No. 10)

Wool yarn—for tails (yellow and red is best)

Deer body hair—natural and dyed (caribou hair is a good body ma te rial also)

Bucktail in various colors—for wings (also polar bear hair)

If you are a tyer of the conventional types of flies, then you probably have most of these materials on hand.

It's best to make your first practice bugs as large as possible. Then, when you become more proficient, you can go on to the smaller sizes.

Begin, 'toy clamping a hook in the vise. Be sure it is clamped securely because you will have to exert quite a bit of pressure on the tying thread.

Next attach the tying thread as you would for the conventional fly (by wrapping one end under itself).

Select a piece of wool yarn about six inches long and tie it in place at the rear of the hook, for a tail. It's best to leave it long until you have tr immed the body hai r to shape. Otherwise you might cut it off during the tr imming operation.

Now we come to the body of the bug. Get out your piece of deer skin and select a bunch of hair about Vs" thick. Cut it off as close to the skin as possible.

Then holding the hai r in your left hand, lay it horizontally on top of the hook. Take two loose tu rns of thread over the middle of the bunch of hair. Start tightening up on the thread, and at the same time letting go of the hair with your left hand.

This causes the hair to twirl around the hook, and flare out, much the same as a feather hackle on a regular dry fly. Pu t quite a bit of pressure on the thread. Push the fibers towards the rea r of the hook and take several turns of thread up against the butts to hold the hair in place. It 's a good idea to tie a couple of half hitches to prevent the thread from slipping.

20 P E N N S Y L V A N I A A N G L E R

Select another bunch of hair and proceed as you did with the first bunch. You can better determine the amount of hair to use after you have tied a few practice bugs. Be sure to keep the bunches of hair as close together as possible. This will insure a tight compact body.

Continue tying in hair until you reach the point where you want to attach the wings. Then, tie four or five tight half hitches in the thread.

Remove the bug from the vise and trim the body to the desired shape. You can also cut the tail to length after the body is t r immed.

AUGUST—1955

Replace the bug in the vise. Select a bunch of bucktail and tie

on at the front of the hook in much the same way as you would tie on the usual upright bucktail wings. Then

divide the wings in two equal parts and criss-cross the thread between them until they lie down in a spent wing position. A drop or two of head cement at the but ts will help them hold their shape.

After the wings are secured by a couple of half hitches, then tie in another bunch of hair at the head of the bug. Tie off the thread with a whip finisher or four or five half hitches, then cut the thread from the hook.

By JOHN F. CLARK (Drawings by the w r i e r )

TOP VIEW

All that remains is to tr im the last bunch of hai r to form the head and then apply several coats of head cement to the thread.

Don't be discouraged if your first attempt looks like something the cat dragged in. With a little practice you should be able to turn out first rate bass bugs.

Here are a couple of color combinations that I've found to work best:

Tail—red ya rn Body—natural brown deer hai r Wings—white bucktail

Tail—yellow and red ya rn Body—alternating bands of brown

deer hair and caribou hair Wings—white bucktail

(Turn to page 32)

21

NEW COMMISSIONER APPOINTED BY GOVERNOR LEADER

JOHN W. GRENOBLE, appointed to serve on the Pennsylvania Fish Commission until the second Tuesday in January, 1958, comes from New Bloomfield, Perry County. He is engaged in engineering and construction

in several parts of the state. He succeeds Major General A. H. Stackpole of Dauphin, who resigned. Grenoble will represent the Sixth District, embracing Dauphin, Lebanon, Cumberland, York, Perry, Adams, Franklin and Lancaster Counties.

Mr. Grenoble, a graduate of Drexel University, received his Masters Degree in Engineering from the University of Alabama. He is married to the former Beatrice L. Hoffman of New Bloomfield, and the father of two children; a daughter, Silver E., a pre-med student at the University of Alabama and a son, William J., who was graduated from Mercersburg Academy June 4, and will enter an engineering course in the University of Alabama this fall.

Prominently identified in local and statewide sportsmen's circles, John Grenoble will be a valuable asset to the Pennsylvania Fish Commission.

OPTIMIST CLUB members helping a young angler measure his fish for the record.

BIG BASS, a 15-inch largemouth, met Ms doom when Robert Bender, Harr isburg put the

steel to him.

Harrisburg Optimists Sponsor Successful Opening Day at Italian Lake July 1

More than 500 youths registered and vied for prizes at the Italian Lake Fishing Project sponsored by the Harrisburg Optomist Club. Some 1500 are expected to participate in the "fishing for youth" movement by the end of the 1955 season when prizes will be awarded to boy or girl for the largest fish in each species caught: bass, carp, catfish, sunfish and bluegills.

The lake has been well stocked with 1500 bass and 600 catfish. Prize winners landed will also be eligible for honors offered b^ Fishing, Inc., of Chicago, a national youth's fishing organization. Last year, the Italian Lake project had two national winners.

WINNERS, l - r—Bi l ly Nordia, 12, Harrisburg, snagged a 13-inch catfish whi le Jerry Kapp,

12, Steelton, displays his 12-inch cat.

BROKEN ARM didn' t keep Douglas Plank, Paxtang, sidel ined. Here he is w i t h bud'" sl inging bai t around w i th one good " i " 9 '

•zz PENNSYLVANIA ANGLER

LINE-UP along Italian Lake. Project is sponsored each year by Harrisburg Optimist Club

vitally interested in youth work.

LAZY FISHER My bait is in the water,

But there's much too much to The bass may strike like fury

And escape for all of me . . . A squirrel swims the river,

Like a fur-clad water snake; Climbs a silvery sycamore

And gives himself a shake. Diamonds drop upon my hand

From his dripping plume— He sees me—tells me off—retreats

To his private room. A catbird in the alders

Is scolding like a shrew, Complaining at my presence

And the work she has to do. Walton's kin comes down the stream—

With four fish on a string: "Any luck today, my friend?"

"I haven't caught a thing!" He smiles a most superior smile—

And hooks another onel . . . Oh, well, I met some woodland friends

And wallowed in the sun. —MARION DOYLE.

Sykesville Club Sponsors First Fishing Rodeo for Youngsters

More than 400 boys, girls and adults at tended the first fishing rodeo sponsored by the Sykesville Sportsmen's Club at Reed's Dam near Sykesville, Pa., on July 2. The dam was stocked with t rout and closed to fishing until after the rodeo. Walter Zilenski, Jr., registrant for the contest, stated more than 200 youngsters under 16 years of age vied for the prizes awarded by the club. Of the 75 fish caught, Pat ty De-church of Sykesville landed the largest fish. She also received prizes for catching the largest fish and the most fish; Gwendolyn Muth, age 3, was youngest girl registered in the contest.

Pete Kruzelac, Jr., Sykesville took a prize for catching largest fish; next largest honors went to Walter Shed-lock of York, Pa. Tied for catching most fish were Lar ry Gulish and John Peace of Soldier, Pa. Youngest boy registered was Donnie Monico, 2, of Sykesville.

Directing the affair were Dean R. Davis, Fish Commission warden and Claud Kelsey, state game protector. Both gentlemen guided the youth in proper use of equipment and explained laws governing fishing. C. R. Mitchell of Lamar, superintendent of Lamar Fish Hatchery and interested club members also helped make the affair a big success.

TAKE A BOY

OR GIRL

FISHING!

Al Larsen, (at extreme right) fishery biologist at the Erie Hatchery, Pennsylvania Fish Commission, points out interesting features of a pound net to viewers of the Sportsman's Club on Erie's WSEE-TV during a recent telecast. Bill Walsh, (center) who conducts the show invited Mr. Larsen to discuss a biologists's work and how it related to better fishing. Earlier in the program Larsen showed how fish are tagged in Lake Erie and Presque Isle Bay so biologists can follow their movements, help Introduce

conservation measures from research.

AUGUST—1955 23

THE TEMPERAMENTAL

YOUGHIOGHENY

(From page 5)

The Youghiogheny is not a gentle river. When heavy rains drench the sharply rising hillsides along its course it booms up at an alarming rate and goes on a violent rampage in a style all its own. It can pile up a million dollars property damage estimate in a few terrifying hours . When a flood strikes, like the one in October, 1954, it is not unusual to see anything from a dwelling to a panic-str icken pig being helplessly swept downstream. Tributaries, normally s m a l l , like Mountz' Creek at Connellsville, become wild enough to overturn tractor-trai ler rigs and rip out s turdy bridges, while the river itself pounds its banks and makes life wretched in every low-lying Yough Valley community—towns such as Smithton, Dawson, West Newton, Connellsville, Friendsville, Confluence, etc. The time has long since passed when the rain-swollen stream was used to profitably float rafts of logs to mills where they'd be t r a n s formed into the much needed lumber of early times.

As far back as 1828 railroads were fighting to en ter Pi t tsburgh via the r iver-carved grade in the Youghiogheny Valley. The most famous of these wrangles was the Balt imore-Philadelphia rivalry. In 1837 a group of men obtained a charter for a ra i l road from Connellsville to Pit tsburgh. But the plan fell through, was r e newed in 1843; and in 1857 the Connellsville - Pi t tsburgh railroad was opened on a cold January day. The panic of 1857 slowed rail traffic, as did the prospects of the Civil War. Later the railway was accused by certain political big-wigs of misusing its charter. This brought on a series of lawsuits, and not until January 1868 did the State Supreme Court set forth a ruling. The favorable nod went to the railroad, and operations resumed. The victor had forever nipped in the bud all dreams of those financially able to establish the river as a big-time cargo carrier. The puffing of engines spelled out overwhelming practical competition for the t ransportation do'llar. Tr iumph was destined to be on the side of the Iron Horse along the echoing hills of the temperamental Yough.

Two large dams are in the upper Yough country. One is at Confluence— the Youghiogheny River Reservoir, a Federal flood control dam with no power generating equipment. It has a breastwork 184 feet high, drains an area of 484 square miles, and provides about 248,800 acre-feet of water storage. Mountain streams tumbling into the reservoir area are helpful in keeping the fish happy. Some very large bass have been taken from the dam, and it is generously alive with young fighting members of the broad-fellow finny tribe. The dam is in Fayette and Somerset Counties, Pennsylvania, and Garret t County, Maryland.

The ether dam, also in Garrett County, actually is not directly on the Yough, bu t is situated on a t r ibutary called Deep Creek. This is Deep Creek Lake, with its depths up to 150 feet, and its astounding abundance of fish— bass, perch, etc. Also, its hundreds of summer cabins dotting a 75-mile shoreline, for this is a resort area; and the waters from the dam, completed in the early 20's, supply the element of power for a two-generator hydro-electric plant. From the powerhouse a tailrace leads the water to the Yough—a distance of only a few hundred feet. Interestingly enough, this plant is owned by the Pennsylvania Electric Company and power generated there is sent over the hills and farmlands to a thriving Pennsylvania city—high and friendly Johnstown in Cambria County.

How did the Youghiogheny get its name? There are so many interpretations of the word that it's difficult to say. But it is generally accepted that the word was derived from the Indians and means "a river flowing in a roundabout course." Both the Delaware and Shawnee Indians are credited with having tossed around such words as Juh-wiah-hanner , Yok-yo-gane, etc. One old map even has it listed as Yoxhio-Geni. Some compromising evidently took place along the way and someone came up with the h a r d - t o -spell Youghiogheny. It has been spelled thus for many decades.

In Washington's expedition of 1754 and in Braddock's expedition of 1755, both men crossed the Yough a number of times at "Stewart 's Crossing at the lower end of Connellsville." Dr. George P. Donehoo's Indian Village and Place Names in Pennsylvania also says: "Washington encamped for several days at Great Crossings, which was near Somerfield, Pa., in order that he might examine the stream, with a

view of transporting supplies by water. He also went to Turkey Foot (Confluence) which he said was a convenient place to build a fort."

Indians of various tribes, including the Iroquois, once occupied land along the Yough. A number of Indian graves have been unearthed during agricultural activities in recent years. About seven miles above Friendsville, Maryland, and within a stone's throw of the Yough, a farmer plowed out a number of Indian skeletons, crude hatchets, "pounding stones" used to make meal from corn, arrowheads, etc. Some very old coins, beads and trinkets were also found in the same field, giving ev i dence that traders, perhaps ill-fated, once were active in the region.

Western Pennsylvania 's first big-time ironmaster, Isaac Meason, operated furnaces on the Yough in the early 1800's. He made kettles and other castings; and today his 20-room home, built in 1802, still is in good condition and is occupied by two families. It is near the Connellsville airport—one of the t ruly splendid old landmarks of the Keystone State.

Perhaps the most unforgettable settler along the Yough of yesteryear was Col. William Crawford. For years he occupied a simple cabin on the west bank of the Youghiogheny at Connellsville. When, in May 1782, General Washington commissioned Crawford to command a regiment of crack-shot soldiers assigned to the task of put t ing down particularly bruta l Indian a t tacks, the fearless leader went to Fort Pitt and set out on the mission tha t was to be his last.

The quest for redskins led Crawford and his 462 men to the Ohio River country near Sandusky. There the cunning Indians, with the help of white renegades, surprised and s u r rounded the entire regiment. Many were killed. Some escaped. Crawford was captured. On June 12, 1782, the Indians burned him at the stake, two hours being required to still his powerful body.

Today a bronze statue cast with diligent care in Crawford's rugged likeness stands on the front-approach grounds of the Carnegie Library at Connellsville. Solemnly, valiantly, steadfastly, it gazes out over the Yough's waters, passive at this point, with dignity and a singular expression of purpose—a fitting memorial to one who gave his life for his country, his State, and especially the scenic Valley of the Youghiogheny which h e so dearly loved.

24 P E N N S Y L V A N I A A N G L E R

LONGNOSE GARS (Lepisosteus osseus), commonly known as gar pike are found in Conneaut Lake and Lake Erie and is one of three species found in the United States. This pre-historic savage killer was a resident of Pennsylvania for thousands of years, remains after animals of the

dim, dark past have long since vanished from the earth.

—Pennsylvania R = h Commission photo by Geo. H. Gordon, chief Photographer.

EARLY AMERICAN SPORTING MAGAZINES

(From page 7)

ing magazine published in America! Not only does it include extremely interesting accounts of American sports, but its contributors include such well known persons as J. Fenimore Cooper, Audubon, Catlin, Elliott, Herbert , Por ter and many others. It is not generally known that the May- June 1839 number contains the first appearance in print of Frank Forester 's (Henry William Herber t ) A Week in the Woodlands. This famous sporting classic was incorporated in book form six years later under the title The Warwick Woodlands; and when a copy appeared at auction in 1945 it realized the sum of 1,100 dollars.

The magazine passed through several ownerships and was finally acquired in 1839 by William T. Porter, a colorful New York sportsman. It continued under Porter 's editorship unti l 1844 when through the unwillingness of

subscribers to pay their subscriptions the publication was discontinued.

The second sporting magazine in America, Porter 's Spirit of the Times made its initial debut Dec. 10, 1831 under the jurisdiction of William T. Porter. Later, when Porter acquired the American Turf Register in 1839, he promised the two papers would not carry identical material . And he was t rue to his word. Whereas the American Turf Register dealt with sports in a serious and informative manner, the Spirit of the Times constantly stressed the lighter side. Extremely humorous sporting accounts—many surpassing those of Surtees, appear in its pages and the best of -these were later e x tracted and published in book form by Porter. Some like The Big Bear of Arkansas, A Quarter Race in Kentucky, Odd Leaves from the Life of a Louisiana Swamp Doctor and Streaks of Squatter Life are pure gems and portray in a realistic manner the dancing, drinking, fighting, tobacco chewing and sporting events contemporary with the period. All are i l lustrated by the famous Darley and bring

fabulous prices when they appear at auction.

The Spirit of the Times is perhaps even more rare than the American Turf Register. No complete file exists and the early numbers are extremely scarce. A supposedly complete set was offered some time ago for $6,000 which gives one an idea of its rari ty. Individual volumes when they appear at auc tion bring up to $100 or more. The paper, folio in size, was published weekly from 1831 to 1861 and comprises 31 volumes.

After the death of Por ter in 1858 the magazine was continued under the editorship of E. E. Jones unti l 1861 when the last issue of Porter 's Spirit of the Times appeared. In 1864 the paper was reactivated by George Wilkes and was then known as Wilke's Spirit of the Times until 1868 when it resumed the title Spirit of the Times. It continued thereafter to furnish sporting information but began to de cline with the appearance of Turf, Field and Farm, eventually died a na t ural death in 1892.

Following the Civil War, Turf, Field

AUGUST—1955 25

'You shoulda been here yesterday, they were bitin' on cloud 944 ."

and Farm, under the editorship of Hamilton Busbey, became the dominant sporting magazine. The paper was folio in size, published weekly and ran from 1865 to 1903. With the appearance of Forest and Stream in 1873 it began to lose subscribers for up to that time it was the only paper that faithfully chronicled American general sporting events. One of the main contributors was Frederick G. Skinner, the son of John S. Skinner, founder of the American Turf Register. Skinner's Reminiscences of an Old Sportsman written over the initials of F. G. S. were of absorbing interest and were reprinted in book form in 1936 by Harry Worcester Smith under the title A Sporting Family of the Old South.

And now we come to perhaps the greatest sporting magazine of them all. On August 14, 1873, Charles Hallock, then forty years old, issued the first number of Forest and Stream, a weekly sporting magazine destined to play an important part on future matters pertaining to the conservation of fish and game in America.

The undertaking was fortunate in its parentage for of all men of his day Hallock was the one most generally equipped to plan the new publication and to successfully launch it. All his life he had been an ardent sportsman; a past master in the art of angling, a genuine lover of woods and wild life, a traveler of rich experience and an explorer who had experienced many an arduous campaign. He possessed an extensive knowledge of the sporting resorts of the country and enjoyed a wide acquaintance with sportsmen, naturalists and public men. He was gifted with a literary style of alluring grace and charm fortified with long experience as a newspaperman. Thus, in every respect, he was admirably fitted not only to project the undertaking but to accomplish the self imposed task.

Up until this time conservation was practically unknown, except by a very few who had the vision to perceive that measures had to be taken immediately to prevent fish and game in the East becoming totally extinct. Fishing was becoming poorer and poorer. When the magazine made its initial appearance the word "sportsman" was in such questionable repute that the "New York Sportsmen's Association" thought it necessary to change their title to tb,e "New York State Association for the Protection of Fish and Game."

The early numbers of Forest and

Stream in addition to its hunting and fishing news—contained articles on Gardening, Baseball, Billiards, Cricket, Croquet, Chess, Turf and Indians. Naturally, the latter gradually faded out of the picture.

Early contributors included Emerson Hough (The Covered Wagon), Thad-deus Norris (The American Angler's Book), Seth Green (Trout Culture), William C. Harris (The Fishes of North America That Are Captured on Hook and Line), Wakeman Holberton (The Art of Angling), Fred Mather (In the Louisiana Lowlands), Robert B. Roosevelt (Superior Fishing), George W. Sears or Nessmuk (Woodcraft). Thomas S. Steele (Canoe and Camera), G. Brown Goode (American Fishes), Charles Lanman (Adventures in the Wilds of North America), the famous fly tyer Sara McBride and a host of others.

From the beginning the magazine was a faithful chronicler of the times. Prices of game in the New York markets were published, but later an active stand was taken by the journal against such market hunting. Here and there one notices a movement started for the protection of fish and game; the determined stand taken against stream pollution and various editorials avowing an organized effort had to be made if any improvement was to be obtained.

Meanwhile Forest and Stream was gaining an enviable record. Subscriptions came pouring in and nine months after the magazine started Hallock sold a one-third interest in the capital stock to William C. Harris for $8,500. Harris then took over the business end

of the publication. Under the guidance of Hallock and Harris the magazine flourished. In 1877 it absorbed Rod and Gun and was henceforth known as Forest and Stream and Rod and Gun. In 1880 Hallock ceased all connection with the journal, having sold out to George Bird Grinnell, who henceforth served as its president. And so it continued until 1930 when publication ceased.

In looking over the files of Forest and Stream one is amazed by the wealth of detail covered. Here one passes through the period of change from the muzzle-loader to the breech loading shotgun; how from vast tracts of sporting country, the game had been annihilated or driven out; how public sentiment had grown in support of wiser conduct and better laws; how the game haunted wilderness had been converted into pleasure resorts and settlements; how fish culture, from the groping experimental stages recorded in 1857 had accomplished economic results of transcendent importance in stocking and restocking the waters. The story of all this had been written from week to week. One need hardly go beyond its file for contemporaneous records on all subjects properly within its scope; effacement of the American buffalo, the introduction of the brown trout, the successful stocking of rivers from the Atlantic westward to the Pacific with valuable food fishes . . . in a word, the growth of sportsmanship.

In comparison with the earlier magazines Forest and Stream cannot be considered rare, yet I doubt if there are more than one or two complete

26 P E N N S Y L V A N I A A N G L E R

files in existence. I have never seen one. At present it can be construed as an embryonic collector's item, and it awaits a more discerning day for its t rue worth to be appreciated.

The American Field sprung into existence in 1874. While the subject mat ter was mainly shooting, hunt ing and dogs, it also included material on yachting, cycling, athletics, na tura l h i s tory and fishing. The weekly is still enjoying a long successful run.

The first American magazine devoted exclusively to fishing was The American Angler. This weekly edited by William C. Harr is ran from 1881 to the early nineteen twenties. Like Forest and Stream its contributors included the foremost anglers of the period. All phases of angling are covered within its pages and particularly interesting are the first American references to dry fly fishing, then a new and fascinat ing method of taking trout on the surface of the water .