PAST GLORIES THE GREAT LIBRARY OF ALEXANDRIA

-

Upload

duonghuong -

Category

Documents

-

view

238 -

download

3

Transcript of PAST GLORIES THE GREAT LIBRARY OF ALEXANDRIA

278

HISTORY OF MEDICINE

PAST GLORIESTHE GREAT LIBRARY OF ALEXANDRIA

Rachel Hajar, MD, FACC*

HEART VIEWS VOL. 1 NO. 7 MARCH / MAY 2000: 278-282

*Director, Non-Invasive Cardiac Laboratory, Cardiology andCardiovascular Surgery Dept., Hamad Medical Corporation,P.O. Box 3050, Doha, Qatar. E-mail:[email protected]

F abled in antiquity for its treasures of wisdom, the Library of Alexandria was the envy of the civilized world.

Alexandria was by no means the first great bookrepository, but because it contained antiquity’smost extensive collection of recorded thought, itundoubtedly was the greatest. The library becamea wonder of the scholarly world, eventuallycontaining, it was said, 700,000 manuscripts, andits facilities included an observatory, zoologicalgardens, lecture halls, and rooms for research.

For nine brilliant centuries, from around 300 BCto the 7th century AD, Alexandria was a place ofinspiration. Alexandria stood as a beacon oflearning and discovery and played a central rolein the development of medical thought andpractice.

The medical books in the library were dominatedby Greek theories. To appreciate fully Alexandria’simpressive position in the evolution of medicaltheory and practice, it is necessary to touch brieflyon the great thinkers, Plato and Aristotle, for theirideas and doctrines were the cornerstones ofWestern thought, which profoundly influencedscience and medicine in the West. Together withHippocrates before them, and Galen afterwards,their doctrines were the roots of pagan, Christian,and Muslim medical thought.

The Great Philosophers

“One might begin with philosophy but would endwith medicine; or start with medicine and findoneself in philosophy.” At first glance, Aristotle’s

“The world of books is the most remarkable creation of man. Nothing else that he buildsever lasts. Monuments fall; nations perish; civilizations grow old and die out; and, after anera of darkness, new races build others. But in the world of books are volumes that haveseen this happen again and again, and yet live on, still young, still as fresh as the day theywere written, still telling men’s hearts of the hearts of men centuries dead.”

Clarence Day, 1874 - 1935

saying may not seem relevant in today’stechnologically advanced medicine. But thequestions that pervade all of philosophy: “Who amI? What is the good life?” are as relevant today asthey were to the ancients because philosophy isa living tradition that has a bearing on how eachof us lives our lives. Indeed, the word, medicine(from Latin medicinus or medicina), refers to aperson, agency, or influence that affects well-being. The ideas of the philosophers Plato andAristotle were among the important influences thatshaped medical thinking.

Plato (c. 429 –347 BC), a contemporary ofHippocrates, a student of Socrates, and theteacher of Aristotle, became one of the mostinfluential thinkers in the history of the Westernworld. Plato’s interests lay mainly in the nature ofthe soul and matter, and his medical speculations,unsupported with direct experimentation, led to anumber of faulty conclusions about the humanbody, which persisted for several centuries. Hismethod of reasoning at a distance rather thanactual anatomy or the bedside signs wasresurrected and perpetuated in the Middle Ages.However, some of his teachings have a bearingon medical practice today, for he expected the idealstate to provide for the health of its citizens and toprevent poverty and overpopulation.

Aristotle (c. 384 – 322 BC), son of a physicianand pupil of Plato, also had a profound influenceon later medicine, especially among the Arabicauthors. Aristotle’s methods were based on carefulinvestigations of both animals and humans, andhis studies were milestones in science. Hedescribed the early development of the heart andgreat vessels and was the first to observe thebeating of the embryo’s heart. He described somedifferences between arteries and veins andidentified and named the great arterial vessel the

279HEART VIEWS VOL. 1 NO. 7 MARCH / MAY 2000: 278-282

aorta. He also taught that the fetus did not breathewhile in the uterus. But he believed in the doctrineof humors and placed the seat of intelligence inthe heart. He confused nerves with ligaments andtendons and linked veins from the liver to the rightarm and from the spleen to the left arm. Hence,he advocated bloodletting on the sidecorresponding to the location of the diseasedorgan.

The doctrines of Plato and Aristotle had a deepinfluence on science and medicine in the MiddleAges and the Renaissance. After the time ofHippocrates, groups of teachers and practitionerssplit into separate medical systems or cults. Greekmedicine after Hippocrates reached its zenith inAlexandria with the founding of its celebratedlibrary.

Founding the Library

Alexander the Great founded and named thecity after himself in 331 BC. He died in 323 BC inIraq. His defeat of the Persian Emperor Darius IIIbrought Egypt within the Hellenistic sphere ofinfluence. The Hellenistic world stretched from theArabian Gulf to Sicily and consequently, there wasa remarkable increase of knowledge aboutanimals, plants, minerals, and drugs.

After Alexander’s death, science gained aprominent place at the court of King Ptolemy, whoruled Egypt from 323 to 282 BC. King Ptolemy’smain cultural creations were the AlexandrianLibrary and the Museum (sanctuary of the Muses).The library gave poets, historians, musicians,mathematicians, astronomers, and scientists anopportunity to live and work under royal patronage.The results were grandly impressive. Euclidworked out the elements of geometry whereasPtolemy mapped the heavens. The poet andscholar Eratosthenes determined thecircumference of the earth. Ctesibius designed awater-clock and built the first keyboard instrument.Archimedes refined his theory that explained theweight and displacement of liquids and gases,Callimachus, the famous poet and librarian,catalogued the huge collection of scrolls andZenodotus produced authentic versions ofHomer’s epics by collating every known text thathe could find.

Collecting treasures of wisdom

Manuscripts and books are essential to sustainand nourish learning, scholarship, and

experimentation. To this end, the Ptolemy dynastyfounded the library “to gather under one roof allthe world’s knowledge”, an ambitious undertaking.Remarkably, that task was assiduously pursuedwith glorious and enriching results.

King Ptolemy I Soter empowered the oratorDemetrios Phalereus, “to collect, if he could, allthe books in the inhabited world.” The king alsosent letters to “all the sovereigns and governorson earth” requesting that they furnish works by“poets and prose-writers, rhetoricians andsophists, doctors and soothsayers, historians, andall the others too.”

Agents were sent out to scout the cities of Asia,North Africa, and Europe, and were authorized tospend whatever was necessary. Every possiblesource was explored, to the point that foreignvessels calling in at Alexandria were searchedroutinely for scrolls and manuscripts. Anything ofinterest found on board was confiscated andcopied. Transcripts were returned in due course,but the originals always stayed in the library. Akey work of Hippocrates carried by a travellingphysician is said to have entered the collection inthis manner. According to Galen, theseacquisitions were so commonplace that they werecatalogued under a special heading, “books of theships.” Galen further asserted that Ptolemy’srepresentatives borrowed the original dramaticworks of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripidesfrom the state archives in Athens by posting fifteensilver talents as a pledge against their safe return.What went back to Athens, however, were copies,the security deposit notwithstanding.

The Ptolemies wanted their Library to beuniversal. Not only should it contain the bulk ofGreek knowledge, but also writings from all nationsto be ultimately translated into Greek. Foremostamong non-Greek works were no doubt, theEgyptian “sacred records” from which Hecataeusof Abdera derived data for his Aegyptica.Manethon, the Egyptian priest who was familiarwith the Greek language and Greek culture,undertook to write a comprehensive history ofEgypt in Greek so that the library should have afull corpus of Egyptian records. Berossos, aChaldean priest, wrote a history of Babylonia inGreek and his book became well known in Egypt.

The “new medicine”

The great center of Greek learning at Alexandriasoon became world-renowned and was theleading medical school in antiquity, attracting

The Great Library of Alexandria

280 HEART VIEWS VOL. 1 NO. 7 MARCH / MAY 2000: 278-282

medical talent. Medical research in the AlexandrianMuseum became famous. Indeed, its reputationlasted long after the Ptolemaic dynasty ended withthe death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC.

Ptolemaic patronage encouraged a more purelyacademic interest, which may have been a distinctadvantage over other centers of study and trainingin medicine. In the Greek world before Alexandria,all members of the medical profession belongedto one tradition, the Hippocratic tradition. Theygenerally were called Asclepidae, in the sense thatthey were the spiritual descendants of Asclepius,the divine founder of the art of healing.

At Alexandria, dissection of corpses was aregular practice, probably for the first time inhistory. The two outstanding medical investigatorsin Alexandria were Herophilus (c. 330 – 260 BC)and his contemporary Erasistratus (c. 330 – 260BC). They were the two leading professors of the“new medicine”, which sprouted. Their writingshave been lost and most of our knowledge of thesetwo is derived from later commentators, especiallyCelsus and Galen in the Roman period. Celsusreported that they dissected, or at leastexperimented upon, living humans (Porter R, TheGreatest Benefit To Mankind, Harper Collins Publishers,London, 1997).

Herophilus had been a pupil of Praxagoras ofCos who was among the first to separate thefunctions of arteries and veins. The great effortsof Herophilus and his school were directed towardsa “scientific” medicine. In contrast with theclassified mass of physical observations anddisease descriptions of the Hippocratic School, theHerophileans were concerned with directknowledge and precise terminology. In order toachieve this, Herophilus embarked upon a newstudy of the human body, based on anatomy andhuman dissection. Tertullian, a representative ofthe Methodists in Rome, bitterly criticizedHerophilus’ pioneer work: “Herophilus thephysician or that butcher who cut up hundreds ofhuman beings so that he could study nature.”

But Galen was genuinely appreciative. Inconnection with the ovarian arteries and veinsobserved by Herophilus in his anatomy of thewomb, Galen admits: “I have not seen this myselfin other animals except occasionally in monkeys.But I do not disbelieve that Herophilus observedthem in women; for he was efficient in otheraspects of his art and his knowledge of factsacquired through anatomy was exceedinglyprecise, and most of his observations were madenot, as is the case with most of us, on brute beasts

but on human beings themselves.”As a result of his anatomical studies on the

nervous system, Herophilus proved that the brainand not the heart was the seat of intelligence, arevolutionary breakthrough for that period since itcontradicted a prevailing Arsitotelian concept.

Correspondingly, medical terminology benefitedfrom Herophilus’ original research work. For thefirst time many human organs were accuratelydefined and their parts and sections given specialmedical terms. Some of them in their Latin formare still in use. He named the duodenum from theGreek for “12 fingers”, this being the length of whathe found. In a number of cases he derived namesfrom the local Alexandrian scene; for example“pharoid”, having the shape of the lighthouse, forthe styloid process; “calamus scriptorius”, for thecavity in the floor of the fourth ventricle of thecerebrum, because it resembled the Alexandrian“writing pen”.

Like the ancient Egyptians, he pointed out thatthe heart transmitted pulsation to the arteries anddescribed extensive variations of the pulse indisease. He observed that the arteries were sixtimes thicker than veins and had different structure.But for all his brilliant, accurate, and objectiveobservations, Herophilus still believed in theancient doctrine of the four humors in histreatment. He used bleeding to evacuate theplethora of the humors.

Some of Herophilus’ pupils founded their ownindependent schools. One school, called EmpiricalSchool, founded by Philinus of Cos, and latersucceeded by Sarapion, a citizen of Alexandria,broke away from the Herophileans. The contrastwith the Herophileans was marked, for while thelatter directed their major energy to the study ofanatomy and physiology, the Empiricist’s interestlay in therapeutics and disregarded anatomy andphysiology, claiming that basically a disease mustbe treated experimentally. They developed theirown medical doctrine based on experiment (peira)or direct knowledge of the circumstances of aparticular case as well as precedent cures forindividual cases (historia).

The gap, however, between these two schoolswas bridged in the last century BC by Heracleidesof Tarentum, the most important Empiricist in theentire history of the Alexandrian school. Hecombined the best of the two schools; he practicedhuman anatomy and also developed surgicaltechniques, while maintaining the experimentalmethod of cure of his school. Among his knownbooks are a work on drugs, a symposium on

The Great Library of Alexandria

281

‘

HEART VIEWS VOL. 1 NO. 7 MARCH / MAY 2000: 278-282

dietetics and a history of the Empirical school.Regrettably, these works have survived only infragments, but Galen wrote a book on theEmpirical School. Only fragments of this book havesurvived in Greek, but the bulk of it has safely comedown to us in Arabic translation.

Erasistratos, Herophilus’ contemporary,emphasized physiological experimentation as wellas anatomical investigation. His main discoveriesconcerned the brain, which like Herophilusregarded as the seat of intell igence. Hedifferentiated between sensory and motor nervesbut confused ligaments with nerves as others hadbefore him. He associated ascites with a “hardliver”, probably cirrhosis. He also described theepiglottis and described its function of blocking offthe air passages during swallowing. He did notbelieve in humoral pathology and believed thatatoms were the basis of the body’s structure.These atoms required pneuma from the inspiredair to be activated and that they circulated inarteries which contained no blood.

The followers of Herophilus and Erasistratuswere involved in spiteful controversies forcenturies. Despite this, the Alexandrian doctorsdiscovered one life-saving technique: the ligatureof blood vessels. This enabled them to performoperations that were not possible before such asremoval of goiters and bladder stones, herniarepairs, and amputations.

In the 2nd century AD, Alexandria’s reputationin the study of medicine attracted Galen, the lastof the great physicians of the ancient world. Theimpact of Alexandrian medical learning on Galenwas so great that in his numerous writings, heimmortal ized much of what we know ofAlexandrian medicine. And as late as the 4t h

century AD the eminent historian AmmianusMarcellinus remarks: “Medicine continues to growfrom day to day, so that a doctor who wishes toestablish his standing in the profession candispense with the need for any proof of it by sayingthat he was trained at Alexandria.”

The fate of the library

In 48 BC during the Roman civil war, Caesar inhot pursuit of Pompey arrived in Alexandria wherehe learned of Pompey’s death and a civil war inEgypt between Cleopatra (fig. 1) and her youngerbrother Ptolemy XIII. Seeing himself outnumberedat sea, Caesar set fire to the ships. The fire spreadbeyond the ships, to other quarters of the city.Plutarch wrote: “When the enemy tried to cut off

his fleet, Caesar was forced to repel the dangerby using fire, which spread from the dockyardsand destroyed the “Great Library.” The 4th centuryhistorian Ammianus Marcellinus wrote of the“burning down by fire of a priceless library of700,000 books during the Alexandrian war whenthe city was destroyed in the time of Caesar.”

Great, indeed, was the loss of the Royal Library;yet, Alexandria was rich in its libraries. TheMuseum, in a separate building from the RoyalLibrary, survived the disaster, and after theannexation of Egypt by Rome in 30 BC, itcontinued to enjoy the protection of the emperors.The Museum hall had a fair collection of books,and the Daughter Library (a branch of the RoyalLibrary), in the Sarapeum (Temple of Sarapis)located in the Egyptian quarter, became theprincipal library in Roman Alexandria. Anotherbuilding, the Caesarion, also had a considerablenumber of books. In addition, it is said that MarkAntony presented to Cleopatra a gift of 200,000books from Pergamun, rival center of learning andculture in antiquity.

Alexandria thrived during the first two centuriesof Roman rule and the existing libraries enabledscholars to carry on the Alexandrian tradition ofscholarship. However, repeated wars andpersecutions took its toll; still intellectual lifecontinued to burn. But in AD 391, the Sarapeumand remaining libraries were totally destroyed bya Christ ian mob. The Christ ian EmperorTheodosius issued a decree sanctioning thedemolition of the temples of Alexandria. Thusbegan the war waged against pagan books byChristian extremists, not only in Alexandria but alsothroughout the empire. Ammianus Marcellinus, thehistorian, speaks of certain people in Rome who“hate learning like [hating] poison” and that“libraries were closed forever like the tomb.”

The Great Library of Alexandria

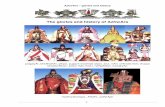

Fig.1. Cleopatra VII (left) and her son by Julius Caesar,Caesarion (right), making offerings. (Temple of Hathor,Dendera)

282 HEART VIEWS VOL. 1 NO. 7 MARCH / MAY 2000: 278-282

A church was built where the Temple of Sarapisonce stood, and in time, Alexandria again becamethe center of a new intellectual movement basedon Christianity.

Arab conquest in AD 642 put an end to Greco-Roman dominion and the center of learning wastransferred to Baghdad in the East and Cordovain the West. Scientific and intellectual life flourishedunder the Arab Empire but no doubt inspired byGreco-Roman scientific heritage. The majorsource of Greek medical books that reached theArabs was through Alexandria. Ibn Abi Sobiah(1204 –1270), a Syrian physician who authored a3-volume book on The Layers of Physicians,wrote: “Most of these [Alexandrian] books existand Al-Razi has referred to them in his book AlHawi.” Al Hawi is the 25-volume Encyclopedia ofMedicine written by Al-Razi (d. 920).

In the beginning of Arab rule in Egypt, 16 booksof Galen were considered the bibles of medicineand formed the core of medical teaching inAlexandria. These were translated into Arabic later.

References:

Mostafa El-Abbadi, Life and Fate of the Ancient Libraryof Alexandria, UNESCO, Paris, 1992.

Albert S. Lyons and R. Joseph Petrucelli II, MedicineAn Illustrated History, Harry N. Abrams Inc., New York, 1987.

Roy Porter, The Greatest Benefit To Mankind, HarperCollinsPublishers, London, 1997.

Jenny Sutcliffe and Nancy Duin, A History of Medicine,Barnes & Noble Inc., New York, 1992.

The Great Library of Alexandria

PTOLEMAIC EGYPT (ALEXANDRIA, 305 – 30 BC)

The Small Pulse, The Big Pulse, Anatomy,Diseases and Symptoms, Fevers, Humors, TheValue of Organs, and Drugs were a few of thebooks written by Galen.

Not a single stone remains of the Great Library,but its glorious life live on in books that it oncesought to shelter.

“Books are the legacies that genius leavesto mankind, to be delivered down fromgeneration to generation, as presents to thoseyet unborn.”

Joseph Addison, AD1672 - 1719© 2000 Hamad Medical Corporation.

When Alexander died in 323BC, his body was brought toEgypt and buried, first atMemphis, and then in a splendidtomb in the new city ofAlexandria. His vast empire wasdivided among his generals andEgypt became the share ofGeneral Ptolemy whosedescendants ruled the countryfor the next 250 years.Alexandria became the capital ofthe Ptolemy dynasty and wasrenowned as a center of Greeklearning. Although the Egyptianswere allowed to go on buildingtemples to their gods, Alexandriawas essentially a Greek ratherthan an Egyptian city. It wasknown as Alexandrea adAegyptum: Alexandria “beside”Egypt rather than within it, as if itwere a separate country in itsown right.

As a family the Ptolemieswere cruel and quarrelsome andthe women were as ruthless asthe men. The most famous of thePtolemies, Queen Cleopatra VII,had already killed an elder sister

and was fighting a war againsther younger brother whenJulius Caesar arrived in Egyptin 48 BC. To save his throneduring a revolt, Cleopatra’sfather had put Egypt underRoman protection and Romewas only waiting for an excuseto make the country part of hergrowing empire.

Cleopatra kept Egyptindependent by winningCaesar’s favor and, afterCaesar’s murder, that of MarkAntony’s. Cleopatra and Antonyboth killed themselves aftertheir defeat by Octavian. Theirlove story is immortalized byShakespeare in his play TheTragedy of Antony andCleopatra.

In 30 BC, Egypt became amere province of the RomanEmpire but Alexandria enjoyedspecial status and continued toflourish as the center ofscientific and intellectuallearning until the 4th century AD,when the city temples and theLibrary were completelydestroyed.

The Greek ruler Ptolemy V (205 – 180 BC) makes offerings to the sacred bull, believedto be the living incarnation of a god and revered since the beginning of Egyptian history.Bull-worship continued under the Ptolemies who introduced the cult of Serapis, a syncreticdeity combining the traits of Greek and Egyptian gods. Temples dedicated to Serapisknown as Serapeum, sprang up in Alexandria and throughout Egypt. The Temple ofSerapis in Alexandria housed part of the Alexandrian Library collection and becamethe principal library after Caesar’s fire destroyed the Royal Library.

278

HISTORY OF MEDICINE

PAST GLORIESTHE GREAT LIBRARY OF ALEXANDRIA

Rachel Hajar, MD, FACC*

HEART VIEWS VOL. 1 NO. 7 MARCH / MAY 2000: 278-282

*Director, Non-Invasive Cardiac Laboratory, Cardiology andCardiovascular Surgery Dept., Hamad Medical Corporation,P.O. Box 3050, Doha, Qatar. E-mail:[email protected]

F abled in antiquity for its treasures of wisdom, the Library of Alexandria was the envy of the civilized world.

Alexandria was by no means the first great bookrepository, but because it contained antiquity’smost extensive collection of recorded thought, itundoubtedly was the greatest. The library becamea wonder of the scholarly world, eventuallycontaining, it was said, 700,000 manuscripts, andits facilities included an observatory, zoologicalgardens, lecture halls, and rooms for research.

For nine brilliant centuries, from around 300 BCto the 7th century AD, Alexandria was a place ofinspiration. Alexandria stood as a beacon oflearning and discovery and played a central rolein the development of medical thought andpractice.

The medical books in the library were dominatedby Greek theories. To appreciate fully Alexandria’simpressive position in the evolution of medicaltheory and practice, it is necessary to touch brieflyon the great thinkers, Plato and Aristotle, for theirideas and doctrines were the cornerstones ofWestern thought, which profoundly influencedscience and medicine in the West. Together withHippocrates before them, and Galen afterwards,their doctrines were the roots of pagan, Christian,and Muslim medical thought.

The Great Philosophers

“One might begin with philosophy but would endwith medicine; or start with medicine and findoneself in philosophy.” At first glance, Aristotle’s

“The world of books is the most remarkable creation of man. Nothing else that he buildsever lasts. Monuments fall; nations perish; civilizations grow old and die out; and, after anera of darkness, new races build others. But in the world of books are volumes that haveseen this happen again and again, and yet live on, still young, still as fresh as the day theywere written, still telling men’s hearts of the hearts of men centuries dead.”

Clarence Day, 1874 - 1935

saying may not seem relevant in today’stechnologically advanced medicine. But thequestions that pervade all of philosophy: “Who amI? What is the good life?” are as relevant today asthey were to the ancients because philosophy isa living tradition that has a bearing on how eachof us lives our lives. Indeed, the word, medicine(from Latin medicinus or medicina), refers to aperson, agency, or influence that affects well-being. The ideas of the philosophers Plato andAristotle were among the important influences thatshaped medical thinking.

Plato (c. 429 –347 BC), a contemporary ofHippocrates, a student of Socrates, and theteacher of Aristotle, became one of the mostinfluential thinkers in the history of the Westernworld. Plato’s interests lay mainly in the nature ofthe soul and matter, and his medical speculations,unsupported with direct experimentation, led to anumber of faulty conclusions about the humanbody, which persisted for several centuries. Hismethod of reasoning at a distance rather thanactual anatomy or the bedside signs wasresurrected and perpetuated in the Middle Ages.However, some of his teachings have a bearingon medical practice today, for he expected the idealstate to provide for the health of its citizens and toprevent poverty and overpopulation.

Aristotle (c. 384 – 322 BC), son of a physicianand pupil of Plato, also had a profound influenceon later medicine, especially among the Arabicauthors. Aristotle’s methods were based on carefulinvestigations of both animals and humans, andhis studies were milestones in science. Hedescribed the early development of the heart andgreat vessels and was the first to observe thebeating of the embryo’s heart. He described somedifferences between arteries and veins andidentified and named the great arterial vessel the

279HEART VIEWS VOL. 1 NO. 7 MARCH / MAY 2000: 278-282

aorta. He also taught that the fetus did not breathewhile in the uterus. But he believed in the doctrineof humors and placed the seat of intelligence inthe heart. He confused nerves with ligaments andtendons and linked veins from the liver to the rightarm and from the spleen to the left arm. Hence,he advocated bloodletting on the sidecorresponding to the location of the diseasedorgan.

The doctrines of Plato and Aristotle had a deepinfluence on science and medicine in the MiddleAges and the Renaissance. After the time ofHippocrates, groups of teachers and practitionerssplit into separate medical systems or cults. Greekmedicine after Hippocrates reached its zenith inAlexandria with the founding of its celebratedlibrary.

Founding the Library

Alexander the Great founded and named thecity after himself in 331 BC. He died in 323 BC inIraq. His defeat of the Persian Emperor Darius IIIbrought Egypt within the Hellenistic sphere ofinfluence. The Hellenistic world stretched from theArabian Gulf to Sicily and consequently, there wasa remarkable increase of knowledge aboutanimals, plants, minerals, and drugs.

After Alexander’s death, science gained aprominent place at the court of King Ptolemy, whoruled Egypt from 323 to 282 BC. King Ptolemy’smain cultural creations were the AlexandrianLibrary and the Museum (sanctuary of the Muses).The library gave poets, historians, musicians,mathematicians, astronomers, and scientists anopportunity to live and work under royal patronage.The results were grandly impressive. Euclidworked out the elements of geometry whereasPtolemy mapped the heavens. The poet andscholar Eratosthenes determined thecircumference of the earth. Ctesibius designed awater-clock and built the first keyboard instrument.Archimedes refined his theory that explained theweight and displacement of liquids and gases,Callimachus, the famous poet and librarian,catalogued the huge collection of scrolls andZenodotus produced authentic versions ofHomer’s epics by collating every known text thathe could find.

Collecting treasures of wisdom

Manuscripts and books are essential to sustainand nourish learning, scholarship, and

experimentation. To this end, the Ptolemy dynastyfounded the library “to gather under one roof allthe world’s knowledge”, an ambitious undertaking.Remarkably, that task was assiduously pursuedwith glorious and enriching results.

King Ptolemy I Soter empowered the oratorDemetrios Phalereus, “to collect, if he could, allthe books in the inhabited world.” The king alsosent letters to “all the sovereigns and governorson earth” requesting that they furnish works by“poets and prose-writers, rhetoricians andsophists, doctors and soothsayers, historians, andall the others too.”

Agents were sent out to scout the cities of Asia,North Africa, and Europe, and were authorized tospend whatever was necessary. Every possiblesource was explored, to the point that foreignvessels calling in at Alexandria were searchedroutinely for scrolls and manuscripts. Anything ofinterest found on board was confiscated andcopied. Transcripts were returned in due course,but the originals always stayed in the library. Akey work of Hippocrates carried by a travellingphysician is said to have entered the collection inthis manner. According to Galen, theseacquisitions were so commonplace that they werecatalogued under a special heading, “books of theships.” Galen further asserted that Ptolemy’srepresentatives borrowed the original dramaticworks of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripidesfrom the state archives in Athens by posting fifteensilver talents as a pledge against their safe return.What went back to Athens, however, were copies,the security deposit notwithstanding.

The Ptolemies wanted their Library to beuniversal. Not only should it contain the bulk ofGreek knowledge, but also writings from all nationsto be ultimately translated into Greek. Foremostamong non-Greek works were no doubt, theEgyptian “sacred records” from which Hecataeusof Abdera derived data for his Aegyptica.Manethon, the Egyptian priest who was familiarwith the Greek language and Greek culture,undertook to write a comprehensive history ofEgypt in Greek so that the library should have afull corpus of Egyptian records. Berossos, aChaldean priest, wrote a history of Babylonia inGreek and his book became well known in Egypt.

The “new medicine”

The great center of Greek learning at Alexandriasoon became world-renowned and was theleading medical school in antiquity, attracting

The Great Library of Alexandria

280 HEART VIEWS VOL. 1 NO. 7 MARCH / MAY 2000: 278-282

medical talent. Medical research in the AlexandrianMuseum became famous. Indeed, its reputationlasted long after the Ptolemaic dynasty ended withthe death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC.

Ptolemaic patronage encouraged a more purelyacademic interest, which may have been a distinctadvantage over other centers of study and trainingin medicine. In the Greek world before Alexandria,all members of the medical profession belongedto one tradition, the Hippocratic tradition. Theygenerally were called Asclepidae, in the sense thatthey were the spiritual descendants of Asclepius,the divine founder of the art of healing.

At Alexandria, dissection of corpses was aregular practice, probably for the first time inhistory. The two outstanding medical investigatorsin Alexandria were Herophilus (c. 330 – 260 BC)and his contemporary Erasistratus (c. 330 – 260BC). They were the two leading professors of the“new medicine”, which sprouted. Their writingshave been lost and most of our knowledge of thesetwo is derived from later commentators, especiallyCelsus and Galen in the Roman period. Celsusreported that they dissected, or at leastexperimented upon, living humans (Porter R, TheGreatest Benefit To Mankind, Harper Collins Publishers,London, 1997).

Herophilus had been a pupil of Praxagoras ofCos who was among the first to separate thefunctions of arteries and veins. The great effortsof Herophilus and his school were directed towardsa “scientific” medicine. In contrast with theclassified mass of physical observations anddisease descriptions of the Hippocratic School, theHerophileans were concerned with directknowledge and precise terminology. In order toachieve this, Herophilus embarked upon a newstudy of the human body, based on anatomy andhuman dissection. Tertullian, a representative ofthe Methodists in Rome, bitterly criticizedHerophilus’ pioneer work: “Herophilus thephysician or that butcher who cut up hundreds ofhuman beings so that he could study nature.”

But Galen was genuinely appreciative. Inconnection with the ovarian arteries and veinsobserved by Herophilus in his anatomy of thewomb, Galen admits: “I have not seen this myselfin other animals except occasionally in monkeys.But I do not disbelieve that Herophilus observedthem in women; for he was efficient in otheraspects of his art and his knowledge of factsacquired through anatomy was exceedinglyprecise, and most of his observations were madenot, as is the case with most of us, on brute beasts

but on human beings themselves.”As a result of his anatomical studies on the

nervous system, Herophilus proved that the brainand not the heart was the seat of intelligence, arevolutionary breakthrough for that period since itcontradicted a prevailing Arsitotelian concept.

Correspondingly, medical terminology benefitedfrom Herophilus’ original research work. For thefirst time many human organs were accuratelydefined and their parts and sections given specialmedical terms. Some of them in their Latin formare still in use. He named the duodenum from theGreek for “12 fingers”, this being the length of whathe found. In a number of cases he derived namesfrom the local Alexandrian scene; for example“pharoid”, having the shape of the lighthouse, forthe styloid process; “calamus scriptorius”, for thecavity in the floor of the fourth ventricle of thecerebrum, because it resembled the Alexandrian“writing pen”.

Like the ancient Egyptians, he pointed out thatthe heart transmitted pulsation to the arteries anddescribed extensive variations of the pulse indisease. He observed that the arteries were sixtimes thicker than veins and had different structure.But for all his brilliant, accurate, and objectiveobservations, Herophilus still believed in theancient doctrine of the four humors in histreatment. He used bleeding to evacuate theplethora of the humors.

Some of Herophilus’ pupils founded their ownindependent schools. One school, called EmpiricalSchool, founded by Philinus of Cos, and latersucceeded by Sarapion, a citizen of Alexandria,broke away from the Herophileans. The contrastwith the Herophileans was marked, for while thelatter directed their major energy to the study ofanatomy and physiology, the Empiricist’s interestlay in therapeutics and disregarded anatomy andphysiology, claiming that basically a disease mustbe treated experimentally. They developed theirown medical doctrine based on experiment (peira)or direct knowledge of the circumstances of aparticular case as well as precedent cures forindividual cases (historia).

The gap, however, between these two schoolswas bridged in the last century BC by Heracleidesof Tarentum, the most important Empiricist in theentire history of the Alexandrian school. Hecombined the best of the two schools; he practicedhuman anatomy and also developed surgicaltechniques, while maintaining the experimentalmethod of cure of his school. Among his knownbooks are a work on drugs, a symposium on

The Great Library of Alexandria

281

‘

HEART VIEWS VOL. 1 NO. 7 MARCH / MAY 2000: 278-282

dietetics and a history of the Empirical school.Regrettably, these works have survived only infragments, but Galen wrote a book on theEmpirical School. Only fragments of this book havesurvived in Greek, but the bulk of it has safely comedown to us in Arabic translation.

Erasistratos, Herophilus’ contemporary,emphasized physiological experimentation as wellas anatomical investigation. His main discoveriesconcerned the brain, which like Herophilusregarded as the seat of intell igence. Hedifferentiated between sensory and motor nervesbut confused ligaments with nerves as others hadbefore him. He associated ascites with a “hardliver”, probably cirrhosis. He also described theepiglottis and described its function of blocking offthe air passages during swallowing. He did notbelieve in humoral pathology and believed thatatoms were the basis of the body’s structure.These atoms required pneuma from the inspiredair to be activated and that they circulated inarteries which contained no blood.

The followers of Herophilus and Erasistratuswere involved in spiteful controversies forcenturies. Despite this, the Alexandrian doctorsdiscovered one life-saving technique: the ligatureof blood vessels. This enabled them to performoperations that were not possible before such asremoval of goiters and bladder stones, herniarepairs, and amputations.

In the 2nd century AD, Alexandria’s reputationin the study of medicine attracted Galen, the lastof the great physicians of the ancient world. Theimpact of Alexandrian medical learning on Galenwas so great that in his numerous writings, heimmortal ized much of what we know ofAlexandrian medicine. And as late as the 4t h

century AD the eminent historian AmmianusMarcellinus remarks: “Medicine continues to growfrom day to day, so that a doctor who wishes toestablish his standing in the profession candispense with the need for any proof of it by sayingthat he was trained at Alexandria.”

The fate of the library

In 48 BC during the Roman civil war, Caesar inhot pursuit of Pompey arrived in Alexandria wherehe learned of Pompey’s death and a civil war inEgypt between Cleopatra (fig. 1) and her youngerbrother Ptolemy XIII. Seeing himself outnumberedat sea, Caesar set fire to the ships. The fire spreadbeyond the ships, to other quarters of the city.Plutarch wrote: “When the enemy tried to cut off

his fleet, Caesar was forced to repel the dangerby using fire, which spread from the dockyardsand destroyed the “Great Library.” The 4th centuryhistorian Ammianus Marcellinus wrote of the“burning down by fire of a priceless library of700,000 books during the Alexandrian war whenthe city was destroyed in the time of Caesar.”

Great, indeed, was the loss of the Royal Library;yet, Alexandria was rich in its libraries. TheMuseum, in a separate building from the RoyalLibrary, survived the disaster, and after theannexation of Egypt by Rome in 30 BC, itcontinued to enjoy the protection of the emperors.The Museum hall had a fair collection of books,and the Daughter Library (a branch of the RoyalLibrary), in the Sarapeum (Temple of Sarapis)located in the Egyptian quarter, became theprincipal library in Roman Alexandria. Anotherbuilding, the Caesarion, also had a considerablenumber of books. In addition, it is said that MarkAntony presented to Cleopatra a gift of 200,000books from Pergamun, rival center of learning andculture in antiquity.

Alexandria thrived during the first two centuriesof Roman rule and the existing libraries enabledscholars to carry on the Alexandrian tradition ofscholarship. However, repeated wars andpersecutions took its toll; still intellectual lifecontinued to burn. But in AD 391, the Sarapeumand remaining libraries were totally destroyed bya Christ ian mob. The Christ ian EmperorTheodosius issued a decree sanctioning thedemolition of the temples of Alexandria. Thusbegan the war waged against pagan books byChristian extremists, not only in Alexandria but alsothroughout the empire. Ammianus Marcellinus, thehistorian, speaks of certain people in Rome who“hate learning like [hating] poison” and that“libraries were closed forever like the tomb.”

The Great Library of Alexandria

Fig.1. Cleopatra VII (left) and her son by Julius Caesar,Caesarion (right), making offerings. (Temple of Hathor,Dendera)

282 HEART VIEWS VOL. 1 NO. 7 MARCH / MAY 2000: 278-282

A church was built where the Temple of Sarapisonce stood, and in time, Alexandria again becamethe center of a new intellectual movement basedon Christianity.

Arab conquest in AD 642 put an end to Greco-Roman dominion and the center of learning wastransferred to Baghdad in the East and Cordovain the West. Scientific and intellectual life flourishedunder the Arab Empire but no doubt inspired byGreco-Roman scientific heritage. The majorsource of Greek medical books that reached theArabs was through Alexandria. Ibn Abi Sobiah(1204 –1270), a Syrian physician who authored a3-volume book on The Layers of Physicians,wrote: “Most of these [Alexandrian] books existand Al-Razi has referred to them in his book AlHawi.” Al Hawi is the 25-volume Encyclopedia ofMedicine written by Al-Razi (d. 920).

In the beginning of Arab rule in Egypt, 16 booksof Galen were considered the bibles of medicineand formed the core of medical teaching inAlexandria. These were translated into Arabic later.

References:

Mostafa El-Abbadi, Life and Fate of the Ancient Libraryof Alexandria, UNESCO, Paris, 1992.

Albert S. Lyons and R. Joseph Petrucelli II, MedicineAn Illustrated History, Harry N. Abrams Inc., New York, 1987.

Roy Porter, The Greatest Benefit To Mankind, HarperCollinsPublishers, London, 1997.

Jenny Sutcliffe and Nancy Duin, A History of Medicine,Barnes & Noble Inc., New York, 1992.

The Great Library of Alexandria

PTOLEMAIC EGYPT (ALEXANDRIA, 305 – 30 BC)

The Small Pulse, The Big Pulse, Anatomy,Diseases and Symptoms, Fevers, Humors, TheValue of Organs, and Drugs were a few of thebooks written by Galen.

Not a single stone remains of the Great Library,but its glorious life live on in books that it oncesought to shelter.

“Books are the legacies that genius leavesto mankind, to be delivered down fromgeneration to generation, as presents to thoseyet unborn.”

Joseph Addison, AD1672 - 1719© 2000 Hamad Medical Corporation.

When Alexander died in 323BC, his body was brought toEgypt and buried, first atMemphis, and then in a splendidtomb in the new city ofAlexandria. His vast empire wasdivided among his generals andEgypt became the share ofGeneral Ptolemy whosedescendants ruled the countryfor the next 250 years.Alexandria became the capital ofthe Ptolemy dynasty and wasrenowned as a center of Greeklearning. Although the Egyptianswere allowed to go on buildingtemples to their gods, Alexandriawas essentially a Greek ratherthan an Egyptian city. It wasknown as Alexandrea adAegyptum: Alexandria “beside”Egypt rather than within it, as if itwere a separate country in itsown right.

As a family the Ptolemieswere cruel and quarrelsome andthe women were as ruthless asthe men. The most famous of thePtolemies, Queen Cleopatra VII,had already killed an elder sister

and was fighting a war againsther younger brother whenJulius Caesar arrived in Egyptin 48 BC. To save his throneduring a revolt, Cleopatra’sfather had put Egypt underRoman protection and Romewas only waiting for an excuseto make the country part of hergrowing empire.

Cleopatra kept Egyptindependent by winningCaesar’s favor and, afterCaesar’s murder, that of MarkAntony’s. Cleopatra and Antonyboth killed themselves aftertheir defeat by Octavian. Theirlove story is immortalized byShakespeare in his play TheTragedy of Antony andCleopatra.

In 30 BC, Egypt became amere province of the RomanEmpire but Alexandria enjoyedspecial status and continued toflourish as the center ofscientific and intellectuallearning until the 4th century AD,when the city temples and theLibrary were completelydestroyed.

The Greek ruler Ptolemy V (205 – 180 BC) makes offerings to the sacred bull, believedto be the living incarnation of a god and revered since the beginning of Egyptian history.Bull-worship continued under the Ptolemies who introduced the cult of Serapis, a syncreticdeity combining the traits of Greek and Egyptian gods. Temples dedicated to Serapisknown as Serapeum, sprang up in Alexandria and throughout Egypt. The Temple ofSerapis in Alexandria housed part of the Alexandrian Library collection and becamethe principal library after Caesar’s fire destroyed the Royal Library.