Paper 3: Rebellion and disorder under the Tudors, 1485-1603

Transcript of Paper 3: Rebellion and disorder under the Tudors, 1485-1603

Sampl

e – F

or re

view a

nd

plan

ning

pur

pose

s onl

y

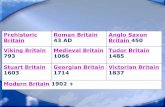

155015401530152015101480 1500

Rebellion and disorder under the Tudors, 1485–1603

KEY QUESTIONS

• HoweffectivewerethekeydevelopmentsinTudorgovernmentandadministration?

• HowdidtherelationshipbetweenthestateandtheChurchchange?

Changes in governance at the centre3.1

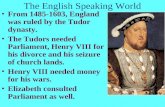

InTRoduCTIonThe first Tudor monarch was Henry Tudor, who became Henry VII in 1485 after his victory over Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth. In the 50 years before Henry came to the throne, England had been torn apart by a civil war between two rival families, who had both claimed the right to be king. As a result of these events, by 1485 the traditional role and powers of the monarchy seemed to be under threat. Henry had many rivals with much better claims to the throne than he, who would be encouraged by his own actions in overthrowing Richard to try the same tactics themselves. But Henry VII survived and went on to found a dynasty that would last for over 100 years. Apart from a brief crisis in 1553, the throne passed from monarch to monarch by inheritance. During this period the power of the monarchy was restored and extended and, although there were challenges to it, the Tudor monarchs were always able to defeat these threats.

How effeCTIve weRe THe key developmenTs In TudoR goveRnmenT and admInIsTRaTIon?The role of the monarchy, nobility and gentry in Tudor EnglandTudor society was based on hierarchy; each person had their place, or rank, and was expected to be obedient to those who were their social superiors. At the top of this structure was God; under God was the monarch. In theory, because they were chosen by God, the monarch could rule as they wished, but in practice, their power was limited because they needed the support of the nobility and gentry to rule the country. Monarchs in the Tudor period had no standing army or police force and were reliant on the nobility and gentry to carry out these roles in local government. A wise monarch would make sure that they both controlled the nobility and gentry, but also listened to them, as they were the eyes and ears of the ruler at a local level. If there was local disorder, it would be the local nobility or gentry who would be responsible for dealing with the trouble. Before Henry VII came to the throne, and during his reign, some nobles joined or led rebellions against the

1485 – Henry VII defeats Richard III at Bosworth

1509 – Accession of Henry VIII

1515 – Hunne case causes anti clerical feeling in parliament

1523 – Parliamentary opposition to high levels of taxation

1529 – Fall of Wolsey; beginning of the Reformation Parliament

1547 – Accession of Edward VI

1549–52 – Radical religious reform, including the First and Second Prayer Books

1504 – Parliamentary opposition to Henry VII’s taxation

1533 – Act in Restraint of Appeals

1534 – Act of Supremacy

1540 – Establishment of new Privy Council

Sampl

e – F

or re

view a

nd

plan

ning

pur

pose

s onl

y

160015901580157015601550

3.1Changes in governance at the centre

monarch. Henry Tudor himself had been a member of the nobility who was able to defeat the king. Noble challenges to the monarchy continued in the early years of his reign, but became increasingly infrequent under Henry VIII and his children. One of the political developments under the Tudors was the increasing control that the monarch was able to exert over their nobility. This was linked to the changing role of the nobility in central and local government.

1555 – Parliamentary opposition to the exiles bill

1562 – Convocation passes the Thirty-Nine Articles

1553 – Accession of Mary Tudor

1597, 1601 – The monopolies debates in parliament

1554 – Repeal of the Act of Supremacy; England returns to Rome

nobility and gentryBelow the monarch were the nobility and gentry. In the period from 1485 to 1603, it was these groups who helped the monarch to govern. The nobility was a group of men who held the highest titles below the king, such as duke, earl or viscount. Under the Tudors, there were between 40 and 60 men who held these titles, with the numbers fluctuating according to royal policy and natural wastage as families died out. The population of England grew from just over two million in the early 16th century to just over four million by 1600. Within this population, the nobility were a tiny, but powerful minority and it is estimated that these families held roughly ten percent of the land that was available for cultivation. The nobles saw themselves as the natural friends, advisers and military leaders of the monarch. They relied on the monarch to protect their lands and property; the monarch in turn relied on them to carry out government locally. When members of the nobility did become involved in rebellion against the monarch, it was usually because this relationship had broken down.

God

The monarch

The nobility: dukes, earls,

viscounts, barons, lords

The gentry: knights, esquires

Yeomen and artisans

Peasants

Vagrants and beggars

figure 1.1 The structure of Tudor society.

1558 – Accession of Elizabeth I

1559 – Establishment of the Elizabethan religious settlement

1576 – Peter Wentworth challenges Elizabeth in parliament

1585 – Beginning of war with Spain; Lord Lieutenants system becomes permanent

Sampl

e – F

or re

view a

nd

plan

ning

pur

pose

s onl

y

12

Rebellion and disorder under the Tudors, 1485–16033.1

Below the nobility, there were about 5,000 gentry families, made up of knights and esquires. In 1490, there were about 375 men with the title of ‘knight’, which meant that they were called ‘Sir’; this number had risen to 600 by 1558, and had declined slightly to 550 by 1603. Esquires were of a slightly lower rank than knights, and did not have a title. Like the nobility, the gentry originally had a military role, but by the Tudor period they too were increasingly involved in local government. The gentry were landowners as well, though their estates were generally less extensive than those of the nobility. Although Tudor society was hierarchical in nature, it was possible to rise through the ranks, through service to the king, marriage or inheritance. Conversely, it was also possible to lose rank, through political miscalculation or because of economic hardship.

yeomen and artisansBelow the land owning elites of Tudor England were the emerging groups known as yeomen and artisans. Yeomen were prosperous farmers who tended to own their own land. Historian John Guy has estimated that there may have been about 60,000 of these men by 1600. Because they owned their lands, these farmers tended to be relatively financially secure because they were less affected by price rises or rent increases. Artisans were skilled craftsmen who often lived in towns or larger villages. Skilled craftsmen became particularly prosperous in the wool and cloth industry, which was the main English export throughout the Tudor period. In the earlier Tudor period, before 1549, it was often members of the yeomanry or skilled craftsmen who provided the leadership and shaped the demands of popular rebellion. This was because they were often better-educated and were the natural leaders of their communities. In the second half of the Tudor period, however, this group was less involved in rebellion as it became more involved in local government.

peasantsAlthough Tudor towns were growing, the majority of England’s population still lived and worked in rural communities, and England’s economy remained based on agriculture. The peasantry worked on the land for the local landlord for wages. Usually, peasants did not own the land on which they lived and on which they were reliant for the production of food for their own survival. They were the most vulnerable to social and economic changes, such as poor harvests, epidemics and price and rent increases. It has been estimated that about two-fifths of the English population were living on the margins of subsistence; any social and economic crisis would be likely to push this group into real hardship, anger and rebellion.

vagrants/beggarsVagrants and beggars were people without masters who roamed the countryside. In Tudor society, they were particularly feared because every person was supposed to be under the control of their social superiors. In addition, this group was seen to be a threat to social order because their movement around England could lead to the spread of rumours and dangerous ideas. As a result, vagrants and beggars were harshly treated and punished under Tudor Acts of Parliament.

1 Make your own copy of the chart in Figure 1.1 and annotate it to show the roles of different social groups in Tudor society.

2 Which group do you think might pose the greatest threat to a Tudor monarch and why?

3 If you were a councillor to a Tudor monarch, what policies would you advise them to follow to improve social and political order?

aCTIvITy knowledge CHeCk

The monarchy and governmentTudor monarchy was personal – as long as the monarch was able to do so, they would make key decisions about policy. Although a sensible monarch would be seen to take advice, even if they did not act on it, they still ruled England and made the important decisions on matters such as religious and foreign policy. Given the importance of the monarch in the government of England, it was essential that the ruler was adult, competent and male – it was assumed that women were incapable of ruling on their own. It was the monarch’s duty to protect their country from invasion (and, if

Sampl

e – F

or re

view a

nd

plan

ning

pur

pose

s onl

y

13

Changes in governance at the centre 3.1

necessary, to lead an army into battle), and to protect the rights and privileges of their subjects; they could not rule exactly how they pleased. Their powers were curbed by Magna Carta (written in 1215) and by the development of other branches of government, such as parliament and the Royal Council. Monarchs who had tried to ignore these constraints, such as Richard II (r.1377–99) and Richard III (r.1483–85), had been labelled tyrants and overthrown.

By 1485, a complex system of government had evolved which could both help and hinder the monarch in their rule. These systems included more informal bodies, such as the Royal Court and, from Henry VII’s reign, the Privy Chamber. There were also more formal institutions, such as the Council, and financial and judicial systems. These institutions were central (national) and, apart from the Court and Privy Chamber, they tended to remain in London, which was the capital city and the seat of government.

what was the Royal Court?Not to be confused with the legal Courts of Justice, the Royal Court served the monarch; wherever the monarch was, the Court would follow. The Court was important for display and entertainment and was an informal source of power. Under the Tudors, those who wanted power or influence would tend to come to the Court in search of patronage. Those who succeeded in gaining patronage at Court could then build up enormous power and wealth, though they remained dependent on access

The monarch

The Court

The Exchequer

Parliament

Central law courtse.g. King’s Bench

Regional councilse.g. the Council of the North

Justices of the Peace

Lords Lieutenant

Sheri�s

Escheators

ChamberHousehold

Privy CouncilSecretary

national government

local government

figure 1.2 The structure of Tudor government

1 Make your own copy of the diagram above. With two colours, highlight the main strengths and weaknesses of the system.

2 What changes might a Tudor monarch make in order to strengthen their control of central government?

3 As you read the next section (pages 12–19), annotate your copy of the chart to show:

a) how each institution worked

b) the changes made to the function of each institution

c) continuities with earlier methods or functions (lack of change).

aCTIvITy knowledge CHeCk

patronageThe distribution of land, offices or favours, through direct access either to the monarch or to their chief ministers.

KEY TERM

Sampl

e – F

or re

view a

nd

plan

ning

pur

pose

s onl

y

14

Rebellion and disorder under the Tudors, 1485–16033.1

to the Court in order to secure this. The Court was also important for display. It was important for the Tudor monarchs to emphasise their power and wealth to important visitors, and the Court allowed them to do this through elaborate and expensive displays, such as tournaments and plays.

what was the role of the Royal Household?The monarch and his family were served by a wide range of people who moved about the country with them. The Household was usually responsible for the ruler’s domestic needs. Hundreds of people were employed in the kitchens, laundries and gardens, and were mostly menial servants, though they were controlled by high-level officials known as the Board of the Green Cloth. The Household could grow or shrink according the personal needs of the monarch and his family, and was sometimes criticised when it became too large and costly. There were occasional attempts to reform how the Household worked and to reduce its expenses: for example, Thomas Wolsey issued the Eltham Ordinances in 1526 to try to achieve this, but they were unsuccessful because Wolsey did not have sufficient control over appointments or the desires and wishes of the king himself.

what was the role of the privy Chamber?Served by the Household, the monarch’s living arrangements were structured in such a way that access to them was closely controlled. As the diagram of the Tudor Palace of Hampton Court shows (Source 1), even the rooms of the Palace were laid out to ensure that the monarch had some privacy. The Great Hall was still used for feasting and formal events, but beyond it was a series of increasingly private rooms. At Hampton Court, this included a guard room – known as the Watching Chamber – through which all visitors had to pass. There was also a Presence Chamber, which was a throne room and where the monarch would dine. It was also a place where news and gossip could flow. Beyond the Presence Chamber was the truly Privy (or private) Chamber, which was actually a series of rooms where the king and his family lived.

Changes made to the structure and function of the Household, 1485–1603The Privy Chamber grew in political importance during the Tudor period. From 1495, when Henry VII increasingly feared betrayal from those he trusted, the Chamber was used to restrict access to the monarch. Henry created the Yeomen of the Guard, who acted as his personal bodyguards and guarded the entrance to his private rooms. Such was Henry’s distrust of those around him that he also used the Chamber to collect and store royal income, which he monitored personally. This system of Chamber finance had the advantage that Henry always had access to ready money, but had the disadvantage that it was a system reliant on the monarch’s ability and interest in controlling royal income. Tudor monarchs after Henry VII did not have the time or inclination to follow this system and the use of Chamber finance lapsed.

David Starkey’s work has shown that under Henry VIII, the Privy Chamber became an important political hub. The Chamber had its own staff, who from 1518 were known as the Gentlemen of the Privy Chamber. The most important of these was the Groom of the Stool, in charge of the royal commode or toilet. Under Henry VIII, these positions were filled by Henry’s most trusted friends, who were usually men from the nobility or gentry. These men were not simply servants. Because of their intimate and daily physical contact with Henry, they were also his advisers and were often also employed in more ‘formal’ areas of government. For example, between 1520 and 1525, Gentlemen of the Privy Chamber were sent on diplomatic missions to France and on a military expedition against the Scots.

The eltham ordinancesReforms which proposed a smaller Council of 20 men who would travel with the king. It was also an attempt to reduce the number of ‘hangers-on’ around the king and thus reduce the size and cost of the Household. Although the Ordinances were presented as a cost-cutting measure, in reality it was another attempt by Wolsey to restrict access to the king and control the political influence of those close to him in the Chamber.

KEY TERM

Access to the monarch via the Privy Chamber was one route to power and influence in the Tudor period and was an opportunity to influence the direction of government. By the 1540s, this also meant control of the dry stamp, which was kept by Gentlemen of the Chamber. Henry VIII’s aversion to paperwork had led to the introduction of the dry stamp as a method of putting the king’s signature to documents quickly and easily. Control of the dry stamp could give its owner enormous power. In the 1540s, the faction led by Edmund Seymour, Earl of Hertford, and John Dudley, Viscount Lisle, gained control of the stamp using members of their faction within the Privy Chamber, notably Sir Anthony Denny. This enabled them to make alterations to the king’s will in their favour in 1547, which brought them increased power and influence in government. Under Edward, a young boy, access to him and to the dry stamp was again controlled through the Privy Chamber, which was filled with supporters of the king’s protectors, first Seymour, then Dudley.

The dry stampAn embossed stamp was made of the king’s signature. This could be stamped onto documents; the signature could then be inked in. Possession of the dry stamp could give the holder considerable power over aspects of government such as grants of land, offices and titles.

factionAn informal group of people at Court who had similar aims or ideas. Factions would seek to influence the monarch by gaining positions which allowed access to their ruler. Factions became increasingly common with the religious and political upheavals of the 1520s and 1530s. They often formed around key individuals with particular religious beliefs; in the 1530s and 1540s, historians often refer to a ‘conservative’ faction which sought a return to Catholicism and Rome, and a ‘reformer’ faction which worked for more religious change.

KEY TERMS

Sampl

e – F

or re

view a

nd

plan

ning

pur

pose

s onl

y

15

Changes in governance at the centre 3.1

PlanshowingthelayoutofHamptonCourtPalaceasitwasduringthereignofKingHenryVIII,fromThe History of Hampton Court Palace in Tudor TimesbyErnestLaw,publishedLondon1885(litho).ThePresenceChamberandPrivyChambercanbeseenonthisplan.

SOURCE

1

HenryVIIIinhisPrivyChamber,apenandinkdrawingbytheartistHansHolbein(c1497–1543).HolbeinwasemployedbyHenryasaCourtartistinthe1530sandwasknownforhisrealisticportraitsofHenryVIIIandmanyofhiscourtiers.

SOURCE

2

How did the role of the privy Chamber change under mary and elizabeth?The role of the Privy Chamber began to change with the accession of female monarchs, Mary and Elizabeth. Because the role of the Chamber involved close physical contact with the ruler, under a woman these roles were filled by other women rather than men. This did not mean that the Chamber lost its political role entirely. Mary’s female attendants, such as Frances Waldegrave and Frances Jerningham, were her former servants who had Catholic sympathies and were married to male members of Mary’s Household, Edward Waldegrave, the Master of the Great Wardrobe, and Henry Jerningham, the Captain of the Guard. These women undoubtedly had influence with the queen. Indeed, Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, wrote to his ambassador Simon Renard to tell him that some of the ladies were taking advantage of their position of trust to gain patronage and favours. In one way, however, Mary kept more control over the Privy Chamber – her dry stamp was kept under lock and key and she seems never to have allowed its use by her administrators. Under Elizabeth, the Chamber continued to decline in political importance. Elizabeth did appoint the wives of her key councillors to her Privy Chamber, for example the wife of the Earl of Leicester, but reforms carried out in 1559 meant that members of her Household were also members of her Council. From then on, politics and major decisions were determined through the formal channels of her Council, rather than through the informal route of the Chamber.

what was the role of the Council?The Royal Council was a more formal body which had existed since medieval times to advise (‘counsel’) the monarch. The monarch chose who should be on their Council and did not have to take their advice, though it was often in their best interests to at least listen to its views. The Council also helped the monarch with the day-to-day running of the country and could act as a judicial court when there were high-profile legal cases which could not be solved through the normal courts of law. In particular, the Council dealt with legal cases relating to the nobility. However, it could also be divided by faction, and its political importance varied depending on the style of rule adopted by different monarchs. The role of the Council did change during the period, however, becoming increasingly formal and ‘professional’ in its role, especially after 1540 (see below on pages 16–18).

what was the role of the Royal Council under Henry vII?Under Henry VII, the Royal Council was a larger, more informal body than it was to become under Henry VIII. Between 1485 and 1509, over 200 men attended Council meetings, though not all at the same time. Henry’s Council consisted of a mixture of members of the nobility, churchmen, royal officials and lawyers. He was careful to include men who had served under his Yorkist predecessors, Edward IV and Richard III; Henry’s Council included 22 men who had served Edward and 20 who had served Richard. As Henry was a usurper, with no experience of government, who had lived most of his life in exile, such men were crucial in helping him to establish and secure his position on the throne. Several, such as John Morton, went on to have long and distinguished careers in his service. Because Henry did not

Look at Sources 1 and 2.

1 What do these sources suggest about the role of the Privy Chamber in Tudor government?

2 Why do you think that this system might have developed?

3 What might be the advantages and disadvantages of this system?

aCTIvITy knowledge CHeCk

Sampl

e – F

or re

view a

nd

plan

ning

pur

pose

s onl

y

16

Rebellion and disorder under the Tudors, 1485–16033.1

hold regular parliaments, his Councils played an important part in gathering information about popular opinion and the mood of the country, as well as advising him on the best policies to pursue. In addition, Henry also made use of ‘Great Councils’. These were special gatherings of all members of the nobility and his Councillors. These were used when Henry needed to be seen to consult his nobility on important issues to do with war and taxation. Henry held five Great Councils between 1487 and 1502; this was a cunning tactic as it made it seem as if he were including all the nobility in his decisions, though in fact he had already made up his mind about what to do. In 1492, for example, when he wanted to end his invasion of France, he made sure that he consulted all his nobility and made them sign a document agreeing to retreat. This tactic also made it harder for the nobility to argue with his decisions.

The Royal Council under Henry vIIIWhen Henry VIII came to the throne in 1509 he was nearly 18. His father, Henry VII, left a Council in place to help his young son to govern. This Council was made up of experienced administrators, such as the Archbishop of Canterbury, William Warham and the Bishop of Winchester, Richard Fox. Both of these men were senior members of the Church hierarchy, which was common for members of the Council in this period. Both also supported Henry VII’s policy of not engaging in expensive foreign wars. This was not a policy supported by the young Henry VIII, who had been trained as a warrior and wished to prove himself against England’s old enemies, France and Scotland. Within two years, Fox and Warham’s influence over royal policy had been undermined; they were replaced by Thomas Wolsey, who rose to power because he was able to give Henry what he wanted – war.

Wolsey remained the dominant influence in politics until 1529, when he fell from power. He was the first of the king’s chief ministers and was responsible for undertaking much of the day-to-day running of government in which Henry had no interest. As a result of Wolsey’s dominance, the Council retained its traditional functions. It was still a fairly large institution of perhaps 40 members, most of whom would not attend on a regular basis. However, in 1526, Wolsey was planning in the Eltham Ordinances to reduce this to 20 men who would meet daily. Although Wolsey’s plans initially came to nothing, by 1540 a Council such as the one he had planned had emerged; this became known as the ‘Privy Council’, and by Elizabeth’s reign was responsible for much of the daily running of the country, especially administration and legal matters.

The reform of the Privy Council, 1540The role of the Privy Council changed considerably in 1540. As part of his ‘Tudor revolution in government’ thesis, Geoffrey Elton argued that the changes to the Council actually occurred in 1536–37, when there was a ‘conscious act of administrative reform designed to modernise the existing King’s Council’. Elton argued that this was part of Thomas Cromwell’s attempt to modernise and reform the government of England, which brought about lasting change to how the Tudor system operated. Most historians would now reject this claim. For example, John Guy argues that

although there were changes to how the Council worked in 1536, these developments were a temporary response to the crisis provoked by the Pilgrimage of Grace in that year. The smaller Council that met in 1536–37 was an emergency body filled with the king’s most trusted advisers. Many of these men were political enemies of Cromwell, such as the Duke of Norfolk. If Cromwell had really instigated these changes, he would not have filled the Council with the men who resented him the most (and were responsible for his fall in 1540). It was only after Cromwell’s fall and execution in 1540, that real and lasting changes to the Council took place.

The changes to the Privy Council which happened in 1540 were permanent ones which lasted for the rest of the period. After Cromwell’s fall, there was a need to restructure Henry VIII’s government so that it could continue to work without Cromwell, who had manipulated his position as King’s Secretary in order to wield power and influence the king. Henry’s reign to 1540 had been dominated by the personalities and influence of his two chief ministers, Thomas Wolsey and Thomas Cromwell. Both of these men had come from relatively humble backgrounds, and their power was resented by the traditional members of the nobility, who saw themselves as the natural advisers of the king. After Cromwell’s fall, the Privy Council turned itself into a ‘chief minister’. This meant that the members of the newly formed Council were collectively responsible for much of the work which had previously been performed by Wolsey and Cromwell. For example, the Duke of Norfolk, a member of the new Council, insisted that anyone wishing to conduct business with the Council should write to them as a group, not to an individual. This change meant that no one individual was able to wield the amount of power on their own that Wolsey and Cromwell had; for the rest of Henry’s reign, there was no ‘chief minister’. This trend continued under Edward and Mary. Under Elizabeth, the man who could have assumed this role, William Cecil, preferred to use his position as the queen’s Secretary instead, and deliberately avoided the use of the term ‘chief minister’, although he did act as such.

To what extent did the membership of the Council and its relationship with the monarch change from 1540?The Council, from 1540, also changed decisively in its membership and its role. From 1540, its membership was considerably reduced and was fixed to include just the most trusted advisers of the monarch. This was in direct contrast to the Council of Henry VII, which had 227 members, many of whom attended only infrequently; before 1536, Henry VIII’s Council had included up to 120 members. From 1540, the membership of the Council was reduced significantly, as Figure 1.3 shows. Although in the reigns of Edward VI and Mary it was not yet fully apparent that these changes were lasting, the trend was continued under Elizabeth, when membership of the Council narrowed still further. The reasons for these fluctuations reflected the individual styles and needs of the monarchs. The number of councillors under Edward VI grew because Edward was a child, and a larger Council was needed in order to govern the country while the king was too young to do so himself. While Edward was under the control of his uncle, Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, the Council’s role was undermined because Somerset preferred to make decisions and rule using men from his own

Sampl

e – F

or re

view a

nd

plan

ning

pur

pose

s onl

y

17

Changes in governance at the centre 3.1

household such as Sir John Thynne. These men were loyal to Somerset and were given key roles in the king’s household and chamber, which allowed them to influence Edward. For example, Somerset’s brother-in-law, Sir Michael Stanhope, was made chief gentleman of the Privy Chamber and groom of the stool; and he also controlled the dry stamp, but Stanhope was never a member of the Council. Although these developments might seem like a reversal of the changes of 1540 and a return to government that was focused on the control of the Privy Chamber, the Council was able to reassert itself, showing that its importance in government had increased. In 1549, when rebellion broke out in the West Country and East Anglia, it was the Earl of Warwick (later the Duke of Northumberland), a member of the Council, who led the attack on Somerset which brought him down. Northumberland, who replaced Somerset as Edward’s protector, was careful to be seen to govern through the Council, reasserting its new importance in Tudor government since 1540. This explains the apparent increase in Council numbers by 1552, though historian Dale Hoak has shown that actually there were about 21 active members. This did not mean that the Council was the most important institution in the country. Power still remained with the monarchy; Warwick was careful to manipulate not only the Council, but also the king, by ensuring that key supporters such as Sir John Gates controlled access to Edward. The decision to implement the ‘devise for succession’ (the plan to remove Mary Tudor from the succession and replace her with Lady Jane Grey), was the work of Edward and Northumberland alone.

Under Mary, a larger number of men were appointed to the Council in an attempt by the queen to be inclusive. However, only a small core of this group were active regularly. Meetings were run by experienced administrators such as William Paget, and returned to the pattern seen in the 1540s. The average attendance at Council meetings in 1555 was 12; only eight councillors attended over 50 percent of meetings. Elizabeth’s reign continued this trend; by the end of her reign, the changes begun in 1540 had become permanent. Not only had the Council become a permanent, small group of trusted advisers, but the focus of their work and their role had also changed.

Henry VII’s reign 227

1509–29 (under Wolsey) 120

1536–37 19

1540 19

1548 22

1552 31

1553–58 50

1559 19

1586 19

1597 11

1603 13

figure 1.3 The Size Of The Council, 1485–1603

How did the work of the Council change from 1540?

To call in the debts and provide for money…

… To give order for the ships and to appoint captains and others to serve in them…

To give order for victuals necessary to be sent to Calais, Berwick etc. [English garrisons]…

To consider what laws shall be established in this Parliament and to name men that shall make the books thereof…

To appoint men to continue in the examination of the prisoners [from Wyatt’s rebellion].

To consider what lands shall be sold, and who shall be in the commission for that purpose…

To appoint a Council to attend and remain at London [Tower]…

To give order for the furniture and victualing of the said Tower…

FromtheCouncil’sregisters,theofficialrecordsoftheCouncil’sactionsandbusinessfromthereignofMary,February1554.ThissectionliststhebusinessdiscussedandwhowastoberesponsibleforactingondecisionsmadebytheCouncil.ThismeetingtookplaceonemonthafterSirThomasWyatt’sunsuccessfulrebellionagainstthequeen.

SOURCE

3

sir Thomas wyatt’s rebellion (1554)Sir Thomas Wyatt and a group of Protestant gentry and nobility plotted a rising in protest over Mary I’s marriage to Philip II of Spain. The marriage was one step in Mary’s plans to return England to full Roman Catholicism, but some Protestants felt threatened by this. The plotters may even have been considering removing Mary and replacing her with her Protestant sister Elizabeth. However, the rebellion failed; Wyatt and his conspirators were imprisoned in the Tower, tried and executed for treason.

EXTEND YOUR KNOWLEDGE

Read Source 3.

1 What do these tasks suggest about the relationship between the Council and the monarch?

2 With a partner, put these tasks in order of priority – which do you think would be the most important of the tasks carried out by the Council? Which would be less important?

aCTIvITy knowledge CHeCk

As the list of tasks from the Council’s registers (Source 3) suggests, the work of the Council from 1540 was increasingly varied. The significance of the changes made in 1540 gave new powers to the Council; it could now issue collective proclamations and orders in the monarch’s name and did not have to wait for explicit instructions from the monarch before it did so. From 1540, it also had its own clerk who recorded meetings. From Mary’s reign onwards, the new role of the Council in government was

Sampl

e – F

or re

view a

nd

plan

ning

pur

pose

s onl

y

18

Rebellion and disorder under the Tudors, 1485–16033.1

as well as control of the monarch’s personal (or privy) seal, which made royal documents official. This meant that the Secretary could be very influential, and in the hands of Thomas Cromwell, the position grew in importance, though this importance was not sustained after Cromwell’s fall.

Although Cromwell was never appointed to the highest office in Tudor government, Lord Chancellor, this did not matter because he was able to manipulate his position as Henry VIII’s Secretary to make himself the most powerful man in the country next to the king. Cromwell had become Henry’s Secretary by 1534. He used his position to control Council meetings and his access to the king’s private correspondence meant that he had detailed knowledge of Henry’s day-to-day business. However, following Cromwell’s fall in 1540, the post of Secretary declined in political importance again. The post was even split between two men for the first time, Thomas Wriothesely and Ralph Sadler, neither of whom was ever as powerful as Cromwell. It is likely that the decision to split the post was partly in response to the increased amount of work which the Secretary undertook. Appointing two secretaries may also have been an attempt to ensure that no one man could exploit the position to his own advantage. The role of Secretary only became more important again when Elizabeth’s most trusted adviser, William Cecil, was appointed to the role in 1558. He continued as Secretary until 1572. Later Secretaries were equally influential; Francis Walsingham, who

reflected in the fact that it had its own seal, though this did not override the dry stamp. Increasingly, the Council was seen as a body which served the state of England, rather than being private servants of the monarch. This did not mean that they supplanted the power of the monarch, who still took key decisions of policy relating to religion, foreign policy and the security of the realm. Moreover, the Council was very much under the control of the monarch. Elizabeth’s Council would meet wherever the queen was staying; often this was at the central palaces of Whitehall or Hampton Court, but when Elizabeth went on progresses, her Council would travel with her. But as Tudor government expanded further into the localities and the volume of administrative work increased, the amount of work done by the Council increased as well. Much of this work was day-to-day administration of the government’s affairs, but the Council had to meet increasingly often to deal with this. In the period from the 1520s to the 1560s, the Council usually had meetings three or four times a week; by the 1590s, it was meeting every day, sometimes twice a day.

sealTudor documents were made official by the use of a wax seal. Hot wax would be poured into a mould to create a design when the wax cooled. A seal also gave a measure of security for secret or controversial instructions. When the seal was broken, it would be obvious that the document had been read. There were a variety of seals which represented different institutions of government. The monarch had their own privy (private) seal; the keeper of this seal could therefore wield great power. The Lord Chancellor had control of the great seal. The fact that the Council also acquired its own seal suggests that it was becoming an important institution of government in its own right.

KEY TERM

The development of the role of Secretary

When the Council meeteth, have a care that the time be not spent in matters of small moment, but to dispatch such things as shall be propounded unto them, for you shall find that they will not meet so often as you would desire, sometimes for sickness and sometimes for other employment… When there shall be any unpleasant matter to be imparted to her Majesty from the Council, or other matters to be done of great importance, let not the burden be laid on you alone but let the rest join with you…

A secretary must have a special cabinet whereof he is himself to keep the key, for his signets, ciphers and secret intelligences… I could wish that the secretary should make himself acquainted with some honest gentlemen in all the shires, cities and principal towns and the affection of the gentry… It is convenient for a secretary to understand the state of the whole realm…

Things to be done with her:

Have in a little paper note of such things as you are to propound to her Majesty and divide it into the titles of public and private suits [requests]… Learn before your access her Majesty’s disposition by some of the privy chamber, with whom you must keep credit, for that will stand you in much stead… When her Majesty is angry or not well disposed, trouble her not with any matter which you desire to have done, unless extreme necessity urge it. When her Highness signeth it shall be good to entertain her with some relation or speech whereat she may take some pleasure.

FromRobertBeale’s‘TreatiseoftheofficeofacouncillorandsecretarytoHerMajesty’(1592).Bealewasbrother-in-lawtoSirFrancisWalsingham,thequeen’sSecretary.BealeworkedasaclerktotheCouncilandwouldstandinforWalsinghamwhenhewasaway.The‘treatise’wasBeale’sadviceonhowtobehaveasaSecretaryandCouncillor.

SOURCE

4

Read Source 4 then answer the following:

1 According to Beale, what were the main duties to be carried out by the Secretary? Which do you think he would consider to have been the most important?

2 Discuss with a partner: what does the type and range of tasks undertaken by the Secretary reveal about his relationship with the monarch and the Council?

3 What would be the advantages and disadvantages for Elizabeth of using a Secretary in these ways?

aCTIvITy knowledge CHeCk

The role of Secretary to the Tudor monarchs first became politically important in the 1530s, when Thomas Cromwell was dominant. Originally, the role was one of personal secretary to the monarch and the Secretary was part of the Royal Household. Holding the position meant close personal access to the monarch,

Sampl

e – F

or re

view a

nd

plan

ning

pur

pose

s onl

y

19

Changes in governance at the centre 3.1

was also Elizabeth’s spymaster, held the office from 1573 until his death in 1590. He was followed by William Cecil’s son, Robert. In this period, although there were always two Secretaries, one was usually much more dominant than the other.

During Elizabeth’s reign, the post of Secretary became permanently important. This was because the men appointed to the post chose to use it to enhance their own power and to conduct the day-to-day running of the government on the queen’s behalf. As the memorandum by Robert Beale suggests, the duties of the Secretary were many and varied. The Secretaries needed to be tactful because they had to deal with the queen; they also needed to ensure that Council meetings were well-run; besides these duties, they also had to sift through enormous amounts of information that were sent to them. Sometimes, the role of the Secretary could be a dangerous one. William Davison, who became Secretary in 1586, had the responsibility of keeping the death warrant which had been issued for the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots, Elizabeth’s Catholic rival for the throne. Davison had to get Elizabeth’s signature for this document, which she gave very reluctantly, telling Davison not to send the warrant, but to keep it safe. The Council decided that the warrant should be sent and Mary was executed. When she found out, Elizabeth was furious and blamed Davison. He was tried, imprisoned and forced to pay a fine of 10,000 marks, a huge amount. Although Davison was eventually released in 1589, he was never employed by the queen again.

The example of Davison shows just how exposed the Secretary’s position could be, as well as the continuing importance of both the Council and the queen in government. It was always the queen who appointed the Secretary; after Walsingham’s death in 1590, she refused to fill his post for six years. Nevertheless, ambitious men continued to want the role because of the great power which came with it. From 1596, when he was finally appointed, Robert Cecil used his position as Secretary to build up a network of supporters. He had access to the queen’s correspondence, which included both information about offices and positions available, as well as requests for these offices. Cecil was able to ensure that patronage was distributed to his own clients, while ensuring that the followers of his rival, the Earl of Essex, were not rewarded.

The establishment of the post of Lord LieutenantTudor central government also extended with increasing directness into local communities, especially through the development of the post of Lord Lieutenant. Before the mid-16th century, local government was carried out by the nobility and gentry and, increasingly, the ‘middling sort’ (the yeomen and artisans). The roles carried out by these groups included presiding over legal cases as Justices of the Peace (JPs) and collecting taxation. In the absence of a standing army or police force, local communities, led by members of the local gentry and nobility, were responsible for upholding law and order and raising armies to fight for the king. Because this role gave considerable power to the land owners, it was important for the monarch to be able to trust them. It was also possible for those in power locally to abuse their position; during the Wars of the Roses, noblemen had

raised armies against their own king. They were also capable of manipulating the local legal system in order to protect their own families and friends. In addition, the system was reliant on local officials, who were unpaid and not necessarily well-suited to their roles. The system of Lord Lieutenants developed over the period as part of the Tudor monarchs’ attempt to solve these problems, especially the recruitment for royal armies, and to increase royal control of the regions.

The first developments in the extension of royal power into the localities and the improvement of military recruitment began in the reign of Henry VIII as a response to the demands of foreign war and the threat of domestic rebellion. In 1512 and 1545, he gave commissions to members of the nobility to organise defence against the threat from France and Scotland, with whom England was at war. In 1536, he issued commissions to deal with the threat posed by the Pilgrimage of Grace rebellion. In 1549, the Duke of Northumberland, who was acting as Protector for the young Edward VI, appointed members of the nobility as Lieutenants to deal with the trouble caused by the serious rebellions of that year. Northumberland’s Lieutenants were expected to have both a policing and a military role at local level. Under Mary I, there was a further attempt to formalise this system, again in response to the demands of war with France. In 1557–58, Mary’s nobility and gentry found it very difficult to muster and recruit troops. Mary’s response was to divide the country into ten lieutenancies, with each Lieutenant being responsible for the defence of their region and military recruitment. However, this was a temporary arrangement which did not survive once the threat of French invasion had diminished in 1558.

Under Elizabeth I, the post of Lord Lieutenant became a permanent one. Once again, the development was in response to the war with Spain, which began in 1585 and lasted until 1604. With the beginning of this war, Lord Lieutenants were appointed to each county, together with a deputy to help them in their work. Many of these appointments were for life because the war lasted so long. Initially, their work was organisation of the war effort; they were responsible for the recruitment of the national militia (army). The commission given to the Lieutenants was to organise the mustering of all available men to fight in the wars; the Lieutenants also had to ensure that their armies were properly armed, trained and disciplined. All local officials were expected to help and obey the Lieutenants. This system was particularly effective because it harnessed the most powerful men in the country, the nobility, in the service of the Crown. Traditionally, the nobility had always seen themselves as defenders of their country; the Lord Lieutenant system reinforced this idea. However, the Lieutenants were directly answerable to the monarch; they were raising troops for a national army, not for their own ‘private’ armies, as had been the case before 1585. If they disobeyed orders, they could be punished. It was also very common for members of the Council to act as Lord Lieutenants as well. This enhanced the links between the central government and the localities, especially because it was the Council who ran the war effort on Elizabeth’s behalf. The Lord Lieutenants were able to gather information about local conditions, which meant that the system of recruitment and military organisation ran more smoothly, although it was possible for local communities to close

Sampl

e – F

or re

view a

nd

plan

ning

pur

pose

s onl

y

20

Rebellion and disorder under the Tudors, 1485–16033.1

ranks against the Lieutenant and refuse to co-operate. This happened in both Suffolk and Wiltshire in the 1590s. Nevertheless, the introduction of the Lord Lieutenant system enhanced the ability of the monarch to control their country more directly than ever before. In some ways, however, the system was not really an innovation, because it still relied on the nobility in their traditional military role.

A Level Exam-Style Question Section C

‘The key factor in upholding and extending royal authority in the years 1485–1603 was the development of the institutions of central government.’

How far do you agree with this claim? (20 marks)

TipYou need to define what is meant by ‘institutions of central government’. This could mean the Secretary, Council or Lord Lieutenants, for example.

How dId THe RelaTIonsHIp beTween THe sTaTe and THe CHuRCH CHange?Church–state relationsParliament was a medieval institution which had gained important powers by the start of the Tudor period. These included: the sole right to grant taxation and the sole right to pass laws (Acts of Parliament). When a monarch needed taxation to supplement their income (usually for war or another emergency), it was usual for them to summon parliament. However, monarchs also retained the right to veto any laws which they did not like, and to summon and dismiss parliament at will. In fact, there were long periods when parliament did not meet at all, and unlike parliament today, it was not involved in day-to-day government. However, most monarchs would call parliament periodically. It was an important opportunity for them to test the mood of the country and to communicate their policies to the Members of Parliament (MPs), and thus to the localities.

How was parliament organised?Parliament had two chambers, the unelected House of Lords, where hereditary peers and Bishops sat, and the House of Commons, which was filled with elected MPs. Two MPs were elected to represent each county of England, and some boroughs (towns) also had the right to send MPs to parliament. To vote in a county, it was necessary to own property which generated income worth 40 shillings (£2) per year. This meant that voting, when it happened, was restricted to those wealthy enough to own property outright. In many cases, however, MPs were elected uncontested – there was no competition for the seat. It was also common for members of the nobility to exercise patronage to ensure their clients were elected. The powerful dukes of Norfolk could usually influence the return of MPs in up to eight boroughs. Parliament, tended to represent the interests of the landed gentry and nobility. To pass an Act of Parliament, a bill had to be heard in both the Commons and Lords before being given royal assent by the monarch. While parliament was usually on the same side as the monarch, this did not mean that it could always be relied on to do what the monarch wanted and, as the century progressed, the Commons became more confident and needed more careful managing. In particular, tensions arose over taxation and finance, religion and the royal succession. These developments were largely due to the changes in the balance of power between state, Church and parliament in the mid-Tudor period.

The role of parliament under Henry vIILike most kings before him, Henry VII was forced to call parliament periodically because he needed grants of taxation to fund wars or the defence of the country from hostile foreign invasion. Because Henry was a cautious monarch who preferred not to pursue an ambitious foreign policy, however, he needed to call parliament increasingly infrequently as his reign progressed. In total, Henry summoned parliament seven times in a reign lasting 24 years; parliament sat for a total of 72 weeks during that period. The last meeting of parliament in his reign was in 1504. To modern eyes, this lack of use of parliament may seem suspicious, but to Henry’s contemporaries, the infrequent parliaments would have seemed entirely usual. England was at peace, Henry did not need taxation, and long gaps between parliaments were not uncommon throughout the Tudor period.

Sampl

e – F

or re

view a

nd

plan

ning

pur

pose

s onl

y

21

Changes in governance at the centre 3.1

Monarch Dates of parliamentary sessions

Henry VII 1485, 1487, 1491, 1495, 1497, 1504

Henry VIII 1510, 1512–14, 1515, 1523, 1529–April 1536, June–July 1536, 1539–40, 1542–44, 1545–47

Edward VI 1547, 1548–March 1549, November 1549–50, 1552

Mary I 1553, April–May 1554, November 1554–55, 1558

Elizabeth I 1559, 1563–76, 1571, 1572–81, 1584–85, 1586–87, 1589, 1593, 1597–98, 1601

SessionsofTudorparliaments,1485–1603–takenfromJ.Loach,Parliament under the Tudors,Oxford(1991).Notethatthesedatesshowthetotalamountoftimeaparticularparliamentwasinsessionbeforenewelectionswereheld.Parliamentdidnotsitcontinuously.

EXTRACT

1

When Henry did call parliament, it was because he needed a grant of taxation. On each occasion, parliament granted the requested money without argument, except in 1504. In the parliament of 1504, Henry was forced to accept a smaller sum in taxation than he had originally asked for, as a result of opposition from the Commons, which was reluctant to grant the sum requested. These tensions had happened before in late medieval England. Since the early 14th century, the Commons had acquired the right to challenge the monarch about taxation and could even threaten to withhold taxation until their grievances had been addressed. During the period, the Commons would occasionally revert to this tactic, though it was very unusual and no Tudor monarch was ever refused taxation.

Slightly less conventionally, Henry used the first parliament that met after his victory at Bosworth to enhance his claim to be king. Parliament acknowledged his claim to the throne and passed a series of Acts of Attainder, convicting Henry’s enemies. However, Henry was careful to use parliament only to make his claim more secure; there was never any suggestion that parliament had the power to grant him his claim to the throne. Henry’s descendants would use parliament to give legal status to the Tudor succession.

act of attainderA medieval innovation which allowed a king to declare someone guilty by Act of Parliament without the need to put them on trial. Under an Act of Attainder, all property of the accused was declared forfeit. This was a particularly powerful political weapon, and Henry VII used it against his Yorkist enemies and those who plotted against him. Acts of Attainder were reversible and Henry used this as a way to control those he did not trust; good behaviour could secure a complete or partial reversal of the original Act.

KEY TERM

The early parliaments of Henry vIII, 1509–23Parliament met only four times between 1509 and 1529: in 1510, 1512–14, 1515 and 1523. Its role in this period was mainly to grant taxation to fund Henry VIII’s wars, because unlike his father, the new king wanted to prove himself on the international stage with wars against England’s traditional enemies, France and Scotland. When his wars were going well, especially in 1513, it was usually not too difficult to persuade parliament to grant taxation for the defence of the realm. However, by 1517, most of the initial gains made by Henry had been lost, and as the burden of taxation increased, with little to show for it, parliament became less keen to grant increasing amounts of money. This was partly because, as landowners, the MPs feared rebellion brought about too much taxation. As members of local society, they were well aware of the amount of grumbling and resistance. In 1523, this led to Wolsey meeting stiff opposition from the Commons to exact the amount of taxation he wanted. By this date, £288,814 had been raised in taxation, not to mention ‘loans’ which had not been repaid, totalling £260,000. Given this burden, it is not surprising that when Wolsey tried to persuade the MPs by addressing them personally, he was met with a stubborn silence.

Apart from the tensions in 1523, however, relations between the king and parliament remained harmonious and there was little alteration in the pattern that had been established by Henry VII. This was to change dramatically from 1529, with the beginning of Henry’s attempt to use parliament to get an annulment of his marriage from Catherine of Aragon.

Sampl

e – F

or re

view a

nd

plan

ning

pur

pose

s onl

y

22

Rebellion and disorder under the Tudors, 1485–16033.1

The role of the Tudor Church before 1529Before 1529, the Roman Catholic Church in England was enormously powerful. Since the early Middle Ages, the Church had grown in wealth and influence. The Church had its own complex structure and hierarchy. At times, this structure would work in harmony with the Tudor monarchy; at other times, there could be serious disputes over control of policy.

At the head of the Catholic Church was the pope, who it was believed was placed in this position by God. Technically, the pope had the power to appoint senior churchmen such as cardinals, archbishops and bishops. In practice, these appointments often reflected the wishes of the English monarchs, especially as England was hundreds of kilometres away from Rome, where the pope normally lived. Roman Catholic beliefs and practices permeated every aspect of ordinary people’s lives. Children were baptised into the Church and later went through a confirmation of their Christian faith. The Church performed marriages and funerals, and was often a key source of alms (charity for the poor) and care for the sick and elderly. Church festivals celebrating important dates in the Church calendar, such as saints’ days, Lent, Easter and Christmas, were key events in most people’s lives, to the extent that most legal documents would be dated by referring to the closest religious festival in date rather than to a weekday or month. The Church taught that Heaven, Hell and Purgatory were real places; how people lived their lives on earth could affect what happened to their souls after death. The Church preached that people could help their souls by performing good works, confessing their sins to a priest, praying to the saints for help, and going on pilgrimages. Attendance at regular Church services was also crucial. The most important part of the service, known as the Mass, was a celebration of the Last Supper which Jesus had with his disciples. Bread and wine would be blessed (consecrated) by the priest and it was believed that, during this process, the bread and wine became the body and blood of Jesus. This belief was known as transubstantiation.

In addition, the Church was the main source of education and learning. The papacy guarded the Church’s right to monitor and censor ideas, and would prosecute those who seemed to challenge its teaching as heretics; if found guilty of heresy, the punishment could include burning at the stake. Church services and the Bible were in Latin, not English, which meant most of the congregation would not have been able to understand what their priest was saying. However, for a clever boy, the Church was the route to power and increased status in society. Churches and monasteries offered boys the opportunity to learn to read and write, and the chance to go to one of the two English universities, Oxford or Cambridge. A career in the Church offered many opportunities to rise to the top of society, despite a lowly background – Thomas Wolsey is a good example of this route into power. He began his career as the son of an Ipswich butcher, yet through a Church education and career, he was able to rise to be Henry VIII’s Chancellor and chief minister.

In the period before 1529, the Church had both supporters and critics, which has led historians to debate its continuing popularity and relevance to ordinary people’s lives. On the one hand, the Church and its clergymen were undoubtedly wealthy and powerful. Humanist thinkers criticised this on the grounds that in the Bible, the original Church was supposed to be poor and its priests were supposed to be humble. In addition, they criticised the Church for its corruption and exploitation of people’s fear of what would happen to their souls after their deaths; the practice of the sale of indulgences was a particular target for criticism. The Church was seen to be out of touch; services in Latin meant that ordinary worshippers could not understand what was being said, while the worship of saints was seen to be both superstitious and non-biblical. Many clergymen held multiple posts (a practice known as pluralism), which meant that they had little contact with the people they were supposed to serve. This antagonism towards the Church is often called anti clericalism.

HumanistHumanist thought emerged in Europe in the later Middle Ages as part of the Renaissance (the ‘rebirth’ of education and thinking). Humanists such as Desiderus Erasmus did not want to break from the Catholic Church, but they were often critical of the superstition, wealth and corruption within the Church. They argued that the Church needed to be reformed from within.

IndulgencesA document which could be bought from Church officials, it offered forgiveness for sins and promised to decrease the amount of time that a soul would spend in Purgatory.

KEY TERMS

On the other hand, it should not be assumed that the break with Rome which occurred under Henry VIII was the inevitable result of anti clerical feeling. The wealthiest in society left money in their wills to pay for priests to pray for their souls after their deaths. The Church was also endowed with vast landed estates, which meant that by the Tudor period it was the biggest landowner in England. In addition, the Church, and the traditions and festivals associated with it, were still a part of everyday life. This was particularly true in the more remote regions of England, such as Yorkshire, Lancashire, Cornwall and Devon. There is also considerable evidence that the Church retained its popularity and appeal as ordinary people continued to make contributions, their local church to buy new jewels and vestments (priests’ clothing). Building or rebuilding local churches was also widespread: almost two-thirds of English parish churches were built or rebuilt during the 15th century. The English Church retained its place as an essential part of everyday life.

purgatoryIn the doctrine of the Catholic Church, it was believed that Purgatory was the intermediate place that existed between Heaven and Hell. It was believed that most people’s souls would go to Purgatory on their deaths. As the name implies, Purgatory was where a soul was ‘purged’: the soul would undergo purification until it was pure enough to go to Heaven. Purgatory was not supposed to be a pleasant place for the soul, which was why prayers for the souls of the dead were so important in shortening the time a soul spent being purified.

KEY TERM

Sampl

e – F

or re

view a

nd

plan

ning

pur

pose

s onl

y

23

Changes in governance at the centre 3.1

AsaleofindulgencesduringtheTudorperiodinEngland.Indulgenceswerepardonsforsins,soldbytheCatholicChurchtoraisemoney.Fromacontemporaryprint.

SOURCE

5

1 Look at Source 5. On your own copy of this picture, label: a) what you can see in the picture; b) what this picture suggests about the role of the Church before 1529.

2 What are the strengths and limitations of this source for a historian trying to find out about the role of the Church in early Tudor England?

aCTIvITy knowledge CHeCk

Relations between the Tudor state and Church before 1529The relationship between the temporal power of the monarch and their government (the state) and the spiritual power of the Church was often harmonious in the period before 1529. At other times in the period, the monarchy and the Church could become rivals. Tensions tended to arise over the power and privileges of the Church, especially when they appeared to be undermining or challenging the power of the monarchy over England; particular flashpoints were the appointment of senior churchmen and the Church’s rights over sanctuary and benefit of clergy. A further source of tension was the ability of the papacy, based in Rome, to intervene in English Church affairs. English monarchs tended to guard their powers and rights to control the English Church very carefully; papal, foreign intervention could be seen as an attack on the power of English kings.

As a usurper, Henry VII particularly needed the support of the Church, as this equated to support from God for his victory at the Battle of Bosworth and the death of Richard III. Henry was careful to uphold the traditional privileges of the Church, except when they seemed to threaten his own power. For example, Henry was prepared to override the sanctuary laws in order to arrest Humphrey Stafford, who had plotted to rebel against him in 1486. In 1489 and 1491, Henry passed laws tightening controls over who could claim benefit of clergy, but this seems to have been part of an attempt to ensure that those claiming this privilege were genuinely members of the clergy. It was not intended as an attack on the Church’s powers. Furthermore, Henry’s relationship with the papacy

sanctuaryUnder English law, anyone accused of a crime could seek sanctuary in a church. This meant that they were protected by the Church from arrest by the authorities. Someone seeking sanctuary could take advantage of this arrangement for 40 days. After this time, they had to give themselves up to the authorities for trial or confess that they were guilty and leave England. Henry VII claimed the right to override this law when the accused person had committed treason (the most serious crime).

benefit of clergyAny criminal who could prove that they were a member of the clergy could be tried in a Church court rather than a royal court and avoid harsher punishments.

KEY TERMS

Sampl

e – F

or re

view a

nd

plan

ning

pur

pose

s onl

y

24

Rebellion and disorder under the Tudors, 1485–16033.1

anticlericalismDislike or criticism of the Church and its clergy. Anticlerical sentiment can found as early as the 14th century; it was not new in the reign of Henry VIII. Although anticlericalism did pave the way for the growth of Protestantism, it was possible to be a member of the Roman Catholic Church, yet be critical of it.

KEY TERM

The Hunne CaseRichard Hunne was a London merchant. In 1511, his infant son died, and the local parish priest asked for the usual mortuary fee (payment for burial). Hunne refused to pay and was sued in the Church courts, which found against him. Hunne was then accused of heresy and sent to the Bishop of London’s prison. In December 1514, Hunne was found hanged in his cell. The Church claimed it was a case of suicide. Despite his death, Hunne was still put on trial for heresy. He was found guilty and his corpse was ceremonially burned. This case caused considerable anger and resentment in London and fuelled anticlericalism in parliament.

EXTEND YOUR KNOWLEDGE

Despite these criticisms, state–Church relations remained relatively cordial in the early years of Henry VIII’s reign. Henry regarded himself as a loyal Catholic – he even published a book, Assertio Septem Sacramentorum (The Defence of the Seven Sacraments), in support of the teachings of the Catholic Church and attacking the ideas of the reformer, Martin Luther. Henry’s chief minister from c1511 to 1529, Thomas Wolsey, was a clergyman. Like Henry VII before him, Henry’s relations with the papacy were good enough for him to be able to secure for Wolsey a whole series of top-level positions in the Church, including the bishoprics of Durham, Bath and Wells, and Tournai (France), which Wolsey held simultaneously. Wolsey was eventually promoted to the second-highest position in the English Church, the Archbishopric of York in 1514. In 1515, the pope also appointed him to the position of Cardinal; this meant that Wolsey was one of the most powerful men in the European Catholic Church, with the power to elect the next Pope and even the potential to become Pope himself.

As Cardinal, Wolsey was more powerful even than the Archbishop of Canterbury. Wolsey would not have achieved these positions if he had not been trusted by both Henry and the papacy, and if Henry and the papacy had not been prepared to co-operate with each other in his appointments. However, Wolsey’s all-powerful position meant that it was easier for him to control both the English Church and the government of the realm, and because of his power the Church lost some of its independence from the monarchy. As a senior churchman, Wolsey’s role was at times ambivalent. He was prepared to make reforms to the Church; between 1524 and 1529, he closed 30 monasteries which had decayed into corruption. But he used the money from these monasteries to found a school in Ipswich and an Oxford college in his name. Wolsey was also Henry VIII’s faithful servant and chief minister. Before 1527, Wolsey was able to be loyal to both the pope and the English monarchy, but from this date, his loyalties became increasingly divided. This was because Henry wanted to get an annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon from the pope; as a loyal servant of the king, Wolsey was obliged to arrange this, but as a senior member of the Church, he also owed obedience to the pope. As a result of these divided loyalties, Wolsey eventually fell from power in 1529 and died on his way to trial in 1530. In the years following his fall, English Church–state relationships changed drastically.

was good. A sign of this was that he was able to ensure that the pope appointed Henry’s own candidate, John Morton, to the top position in the English Church, Archbishop of Canterbury.

In the first 20 years of Henry VIII’s reign, this trend continued, although there were occasional flashpoints. Anticlericalism did exist in Tudor England and was sometimes expressed in parliament. A good example of this was the parliaments which met in the years between 1512 and 1515. In 1512, there was another Act to limiting benefit of clergy, although on its own, this Act may be seen as a continuation of the process begun by Henry VII. In the parliament that met in 1515, however, anti-clerical feeling was exacerbated by the Hunne affair, in which a rich London merchant accused of heresy had been found dead while in the Bishop of London’s prison. The Church claimed that he had committed suicide, but it was rumoured that Hunne had been murdered. Parliamentary criticism in this case focused on the power and corruption of the Church.

Sampl

e – F

or re

view a

nd

plan

ning

pur

pose

s onl

y

25

Changes in governance at the centre 3.1

martin luther and reformer ideasMartin Luther was a German monk who challenged the teachings of the Catholic Church. His Ninety-Five Theses (1517) attacked practices such as the granting of indulgences. Luther went on to reject Catholic teaching on Purgatory and transubstantiation. His ideas were spread widely across Europe and influenced some English courtiers, such as Thomas Cromwell, Thomas Cranmer and Anne Boleyn. Luther’s reformer ideas eventually became known as ‘Protestantism’.

EXTEND YOUR KNOWLEDGE

1485Henry Tudor becomes king after victory at

Bosworth1515

Thomas Wolsey appointed cardinal by the pope

1529Fall of Wolsey

1534Act of Supremacy

1552Second Book of Common Prayer published

1547Accession of Edward VI who had reformer views

1549First Book of

Common Prayer published

1554Act of Supremacy

repealed; Mary returns England to Rome 1559

Accession of Elizabeth I who was cautiously Protestant

1559Second Act of Supremacy and Act of Uniformity

1486Henry’s right to be king confirmed by the papacy

1527Henry begins annulment proceedings

TIMELINE: RELATIONS BETWEEN THE CHURCH AND STATE, 1485–1603

1533Act in Restraint of Appeals

1562Convocation publishes the Thirty-Nine Articles

1577Elizabeth suspends Edmund Grindal, Archbishop of Canterbury

1587Anthony Cope and Peter Wentworth attempt

to introduce their own Prayer Book through parliament

1593Act against Seditious Sectaries

1566The ‘vestments controversy’ leads to the

publication of the ‘Book of Advertisements’

1 Make lists to show the strengths and weaknesses of the Church from 1485 to 1529.

2 Why do you think the relationship between the monarchy and the Church was sometimes tense? What could be done to resolve these problems?

aCTIvITy knowledge CHeCkSam

ple

– For

revie

w and

plan

ning

pur

pose

s onl

y

26

Rebellion and disorder under the Tudors, 1485–16033.1

background to the act of supremacy (1534)In 1527, Henry VIII began to challenge the legality of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon. After 18 years of marriage, Catherine had produced one living daughter, Princess Mary, but no living son. She was now past child-bearing age and Henry had fallen for the younger Anne Boleyn. During the 1520s, Henry became convinced that he was being punished by God for marrying Catherine. In Henry’s eyes, God had not granted him the son and heir he so desperately wanted to secure his dynasty. As a result, Henry decided to seek an annulment of his marriage to Catherine from the pope. Unfortunately for Henry, he was unable to get his annulment from Catherine. The pope, Clement VII, was under the control of Catherine’s nephew, Charles, the Holy Roman Emperor and ruler of Spain. Because of this, Clement was unable to give Henry an annulment. By 1529, Henry was frustrated and looking for another method to end his marriage and marry Anne. Wolsey had fallen from power as a result of his inability to help Henry; in his place, Thomas Cromwell began to rise in Henry’s service. It was Cromwell who found the solution to Henry’s problems by using parliament to break from papal control and to place Henry at the head of the English Church. This, in turn, allowed Henry to announce that his marriage to Catherine was void. Although neither Henry nor Cromwell was thinking of the long-term consequences of their actions, the results of the break with Rome would have a permanent impact on the relationships between the state, Church and parliament.

annulmentThe annulment of a marriage means that the marriage was never valid in law. It is different from a divorce, which ends a marriage which has broken down, but was legal to begin with.

KEY TERM

1529Mortuaries Act

1533January: Anne Boleyn’s pregnancy is

announced; Henry marries Anne in secret

April: Act in Restraint of Appeals

May: Henry’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon is annulled by Thomas Cranmer (Archbishop of

Canterbury)

1536Act for Extinguishing the Authority of the

Bishop of Rome

1532Act in Conditional Restraint of Annates

Submission of the Clergy

1534Succession Act

Act of Supremacy

Treason Act

TIMELINE: KEY ACTS OF THE REFORMATION PARLIAMENT, 1529–36

annatesPayments which churchmen made to Rome when they were appointed to a new position in the Church.

ConvocationThe Church’s own version of parliament which included representatives of local parish clergy plus bishops. Convocation was split into a lower and upper house, and was responsible for deciding how much tax the Church should pay to the monarchy and for making its own canon (Church) laws. The power of Convocation was attacked by Henry VIII in the 1530s.

KEY TERMS

From 1532, Thomas Cromwell had risen to become Henry’s chief minister and he took charge of the king’s attempts to get an annulment from Catherine. Parliament had been called in 1529, in an attempt to put pressure on the papacy to grant an annulment. Before Cromwell’s rise to power was complete, parliament had already been used to threaten the English Church through the passing of the Act in Conditional Restraint of Annates, which put a temporary stop to payments to Rome and was the first step on the path that was to lead to complete rejection of the pope’s power in England. Cromwell took advantage of the anti clerical feeling in the Commons to take the pressure on the Church further. In 1532, he used anti clerical feeling to force the clergy of the English Church to submit to Henry. In the Submission of the Clergy, English churchmen agreed to accept Henry’s power over them; they were not allowed to call Convocation without his permission, nor were they allowed to pass canons (Church laws) without his agreement. Through these early Acts, Henry and Cromwell restricted the legal and financial power of the English Church.

Sampl

e – F

or re

view a

nd

plan

ning

pur

pose

s onl

y

27

Changes in governance at the centre 3.1