Palawan Asset Accounts

-

Upload

no-to-mining-in-palawan -

Category

Business

-

view

2.632 -

download

21

description

Transcript of Palawan Asset Accounts

ENVIRONMENTAL AND NATURAL RESOURCES ACCOUNTING II PROJECT PALAWAN ASSET ACCOUNTS Fishery, Forest, Land/Soil, Mineral and Water Resources

Palawan Council for Sustainable Development Staff

National Statistical Coordination Board

United Nations Development Programme

ii

FOREWORD In 1994, the Palawan Council for Sustainable Development Staff (PCSDS) and the Provincial Government, together with the National Statistics Office (NSO) and the Bureau of Agricultural Statistics (BAS), had the occasion of working with the National Statistical Coordination Board (NSCB) for the pilot-testing of the compilation of the Gross Provincial Domestic Product. A first attempt at sub-regional disaggregation of the GDP, this exercise provided the basis for determining Palawan’s contribution to the national economy. This activity likewise paved the way for identifying the areas for improvement of the statistical data collection system in the province. As an offshoot of this undertaking, Palawan was again selected in 1998 as the pilot area for the institutionalization of the Philippine Economic-Environmental and Natural Resources Accounting (PEENRA) System at the provincial level. Focusing this time on the valuation of the asset accounts for five resources of Palawan, this activity was able to show that environmental and natural resources accounting could be successfully carried out at the sub-national level. Such activity could not have been achieved without the support and cooperation of the various data producing agencies operating in the province. On behalf of the Provincial Government of Palawan, I would like to extend our gratitude to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the sponsor of the second phase of the Environment and Natural Resources Accounting Project, NSCB and the United Nations Statistics Division (UNSD), for the technical guidance provided to us. I also commend the heads of agencies and technical staff who had actively participated in pursuing the realization of the objectives of this project. We take great pride that Palawan had initiated this worthwhile endeavor. Through this publication, we hope to disseminate the experience and outputs of Palawan as a pilot model towards the establishment of a provincial asset accounts of interested provinces. JOEL T. REYES Governor Province of Palawan

iii

FOREWORD This report contains the output of the technical working groups from 14 national agencies and local government offices in Palawan who were involved in the Environment and Natural Resources Accounting (ENRA) II Project. Funded by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the ENRA II Project included a provincial component which aimed to institutionalize the Philippine Economic-Environmental and Natural Resources Accounting (PEENRA) System at the provincial level. Following the methodologies adopted during the first phase of the project, asset accounts for five resources of Palawan, namely: land and soil, forest, fishery, mineral and water, were compiled by a technical working group for each resource. As the lead implementing agency in the province, the Palawan Council for Sustainable Development Staff (PCSDS) had spearheaded the operationalization of the project. To effectively undertake our tasks, we sought the participation of national agencies (Bureau of Agricultural Statistics, Department of Agrarian Reform, National Irrigation Administration, National Statistics Office, and the Department of Environment and Natural Resources) and the offices of the Palawan Provincial Government (Provincial Planning and Development Office, Office of the Provincial Agriculturist and the Environment and Natural Resources Office) and Puerto Princesa City Government (City Planning and Development Office and City Environment and Natural Resources Office). The Palawan Tropical Forestry Protection Programme, a project of the PCSDS and the Paltubig, Inc. were also active partners in this undertaking. Their participation and untiring support were instrumental in the achievement of the project’s objectives. All our efforts however could not have been effectively carried out without the guidance and supervision of the National Statistical Coordination Board (NSCB), the project’s overall lead executing agency. Indeed we are grateful for the opportunity given to us by NSCB and for their confidence that our provincial leaders and policy makers will find this project a significant exercise. The skills that were imparted to us by the NSCB staff will be put into test when we update the accounts in the future. The PCSDS fervently hopes that the cooperation shown to us by the various agencies with whom we have worked with will continue as we pursue the ultimate objectives of the PEENRA system.

JOSELITO C. ALISUAG Executive Director PCSDS

iv

FOREWORD Towards the Institutionalization of the Philippine Economic-Environmental and Natural Resource Accounting (PEENRA) System at the Provincial Level, the National Statistical Coordination Board is pleased to have been a part of the “Palawan Provincial Asset Accounts”, a product of the Environmental and Natural Resource Accounting II (ENRA II) Project funded by the United Nations Development Programme. Palawan, is so far the only province that has its own Provincial Product Accounts. As a pioneering output in environmental accounting at the subnational level, it is hoped that the Palawan Provincial Asset Accounts will greatly contribute to the development of Palawan and will serve as a model for other provinces. Indeed, this compilation of environmental resource accounts in Palawan from 1988 to 1999 covering six (6) resources namely land/soil, fishery, mineral, forest, water and wildlife resources, is a potent medium to bring to the fore the importance of environmental protection at the subnational level. The NSCB salutes the Palawan Council for Sustainable Development Staff for its dedicated work in pursuing the realization of environmental accounting in the province. The close collaboration among the various stakeholders -- the Provincial Government, other government agencies, non-government organizations and private institutions in Palawan, and the individual members of the Provincial Steering Committee and the Technical Working Groups (TWGs), is an experience that should inspire other provinces who wish to undertake the same activity. We acknowledge the United Nations Statistics Division (UNSD) for the technical assistance given and the UNDP for the financial support extended to the ENRA II Project.

ROMULO A. VIROLA Secretary General, NSCB

v

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Foreword List of Tables viii List of Figures xii List of Appendix Tables xv Executive Summary xviii CHAPTER 1. MARINE FISHERY RESOURCE 1.1 Introduction 2 1.2 Conceptual Framework 3

1.2.1 Scope and Coverage 3 1.2.2 Framework of the Asset Account 3

1.3 Operationalizing the Framework 5

1.3.1 Sources of Data 5 1.3.2 Estimation Methodology 5

1.4 Results and Discussion 7

1.4.1 Share of the Fishery sector to GPDP 7 1.4.2 Fish Catch and Fishing Effort 7 1.4.3 Sustainable Yield and Depletion 8

1.5 Recommendations 10 Acronyms 12 Definition of Terms 13 References 14 CHAPTER 2. FOREST RESOURCE 2.1 Introduction 16 2.2 Conceptual Framework 17

2.2.1 Scope and Coverage 17 2.2.2 Framework for the Asset Accounts 17

2.3 Operationalizing the Framework 18

2.3.1 Sources of Data 18 2.3.2 Estimation Methodology 19

2.4 Analysis, Results and Discussions 22

vi

2.4.1 Old Growth Dipterocarp Forest 22 2.4.2 Second Growth Dipterocarp Forest 25 2.4.3 Mangrove Forest 27 2.4.4 Rattan 29

2.5 Recommendations 31 Acronyms 33 Definition of Terms 34 References 48 CHAPTER 3. LAND/SOIL RESOURCE 3.1 Introduction 50 3.2 Conceptual Framework 50

3.2.1 Scope and Coverage 50 3.2.2 Framework for the Asset Accounts 50

3.3 Operationalizing the Framework 53

3.3.1 Sources of Data 53 3.3.2 Estimation Methodology 54 3.3.3 Underlying Assumptions and Limitations 57

3.4 Result and Discussion 58

3.4.1 Physical Asset Accounts 58 3.4.2 Monetary Accounts 63 3.4.3 Summary of the Land and Soil Resource 66

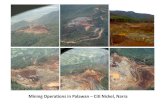

3.5 Recommendations 67 Acronyms 69 Definition of Terms 70 References 87 CHAPTER IV. MINERAL RESOURCE 4.1 Introduction 90 4.2 Conceptual Framework 92

4.2.1 Scope and Coverage 92 4.2.2 Framework for the Asset Account 92

4.3 Operationalizing the Framework 93

4.3.1 Sources of Data 93 4.3.2 Estimation Methodology 94

vii

4.4 Results and Discussion 95

4.5.1 Physical Asset Account 95 4.5.2 Monetary Account 97

4.5 Recommendations 98 Acronyms 100 Definition of Terms 101 References 108 CHAPTER 5. WATER RESOURCE 5.1 Introduction 110 5.2 Framework for the Asset Account 111

5.2.1 Scope and Coverage 111 5.2.2 Framework for the Asset Account 111

5.3 Operationalizing the Framework 112

5.3.1 Surface Water 112 5.3.2 Groundwater 112

5.4 Analysis, Results and Discussion 116

5.4.1 Physical Accounts of Surface Water 116 5.4.2 Physical Accounts of Groundwater 117

5.5 Limitations 119 5.6 Recommendations 119 Acronyms 121 Definition of Terms 122 References 130

viii

LIST OF TABLES

Table Number Title Page

CHAPTER 1. MARINE FISHERY RESOURCE

1.1 Gross Provincial Domestic Product Accounts, (Palawan 1988 and 1994) ……………………………. 7

1.2 Estimated Volume of Catch and Fishing Effort

of Marine Fishery resource, Palawan, 1983-1998 … 8 1.3 Estimated Marine Fishery Resource Depletion,

Palawan, 1983-1998 ….………………………….…… 9 CHAPTER 2. FOREST RESOURCE

2.1 Area Accounts of Old Growth Dipterocarp Forests, 1988-1999 (in hectares)…………………….. 23

2.2 Volume Accounts of Old Growth Dipterocarp

Forests, 1988-1999 (in thousand cubic meters)……. 23

2.3 Economic Accounts of Old Growth Dipterocarp Forest at Current Prices, 1988-1999 (In million pesos)……………………………………….. 24

2.4 Economic Accounts of Old Growth Dipterocarp

Forest at Constant Prices, 1988-1999 (In million pesos)……………………………………….. 24

2.5 Stumpage Value for Natural Forest Stands at

Current Prices, 1988-1999……………………………. 25

2.6 Area Accounts of Second Growth Dipterocarp Forests, 1988-1999 (in hectares)…………………….. 25

2.7 Volume Accounts of Second Growth Dipterocarp

Forests, 1988-1999 (In thousand cubic meters)……. 26

2.8 Economic Accounts of Second Growth Dipterocarp Forest at Current Prices, 1988-1999, (In million pesos)…………………………. 27

2.9 Economic Accounts of Second Growth

Dipterocarp Forest at Constant Prices, 1988-1999, (In million pesos)………………………… 27

2.10 Area Accounts of Mangrove Forests, 1988-1999….. 28

ix

Table Number Title Page

2.11 Volume Accounts of Mangrove Forests, 1988-1999, (In thousand cubic meters)…………….. 28

2.12 Rattan Resources Volume Accounts, 1988-1998

(In thousand lineal meters)…………………………… 29

2.13 Economic Accounts of Rattan at Current Prices, 1988-1991 (In million pesos)………………………… 31

2.14 Economic Accounts of Rattan at Constant Prices,

1988-1991 (In million pesos)………………………… 31

CHAPTER 3. LAND/SOIL RESOURCE

3.1 Sources of Data on Lands Devoted to Forestry, Agriculture and Built-up Uses………………………… 54

3.2 Physical Asset Account of Land Resources

Devoted to Forest Uses, Mainland Palawan, 1988-1998……………………………………………… 59

3.3 Physical Asset Account of Land Resources

Devoted to Agricultural Uses, Palawan, 1988-1998……………………………………………… 60

3.4 Physical Asset Account of Land Resources

Devoted to Built-up Uses, Palawan, 1988-1998……………………………………………… 60

3.5 Physical Asset Account of Soil Resources

Devoted to Forest Uses, Mainland Palawan, 1988-1998……………………………………………… 61

3.6 Physical Asset Account of Soil Resources Devoted to Agricultural Uses, Palawan, 1988-1998……………………………………………… 61

3.7 Adjusted Physical Area of Forest Lands by Type of Forest, in Hectares, Mainland Palawan, 1988-1998……………………………………………… 62

3.8 Adjusted Physical Area of Agricultural Lands by Type

of Farm, In Thousand Hectares, Palawan, 1988-1998………………………………………………. 62

3.9 Adjusted Physical Area of Built-up, In Hectares,

Palawan, 1988-1998…………………………………… 63

x

Table Number Title Page

3.10 Monetary Estimate of Land Resources Devoted to Forest Uses, Mainland Palawan, 1988-1998……………………………………………… 63

3.11 Monetary Estimate of Land Resources Devoted to Agricultural Uses, Palawan, 1988-1998……………………………………………… 64

3.12 Monetary Estimate of Land Resources Devoted to Built-up Uses, Palawan, 1988-1998……………………………………………… 64

3.13 Monetary Estimate of Soil Resources for Lands Devoted to Forest Uses, Mainland Palawan, 1988-1998……………………………………………… 65

3.14 Monetary Estimate of Soil Resources for Lands Devoted to Agricultural Uses, Palawan, 1988-1998……………………………………………… 65

3.15 Summary Table of Physical Asset Account of Land Use by Year, Palawan, 1988-1998………………….. 66

3.16 Summary Table of Monetary Asset Account of Land

Use by Year, Palawan, 1988-1998………………….. 67 CHAPTER 4. MINERAL RESOURCE

4.1 Mineral Deposit in Palawan, 1981………………..… 91

4.2 Nickel Physical Asset Accounts in Ore Form……… 96

4.3 Nickel Physical Asset Account in Metal Form…….. 96

4.4 Sand and Gravel Physical Account………………… 97

4.5 Nickel Monetary Account (Using Net Price Method at 15% Interest Rate, In Peso)……………. 98

4.6 Sand and Gravel Monetary Account (Using Net Price Method at 15% Interest Rate, In Peso)……… 98

CHAPTER 5. WATER RESOURCE

5.1 Physical Accounts Framework for Surface and Groundwater……………………………………….…. 111

5.2 Estimation Methodology and Sources of Data……. 114

xi

Table Number Title Page 5.3 Surface Water Physical Asset Account of Palawan,

1988-1998 (MCM)……….…………………………… 116

5.4 Physical Account of Groundwater in the Province of Palawan , 1988-1996 (MCM)…………………….. 118

xii

LIST OF FIGURES Figure Number Title Page CHAPTER 1. MARINE FISHERY RESOURCE

1.1 Catch by Commercial and Municipal Fishery Industry, Palawan, 1983-1998……………………… 2

1.2 Asset Accounts Framework for Fishery Resource… 4

1.3 Total Catch and Total Fishing Effort, Palawan,

1983-1998……………………………………………… 8

1.4 Sustainable Yield Effort Curve for Marine Fishery Resources, 1983-1998……………………………….. 10

CHAPTER 2. FOREST RESOURCE

2.1 Asset Accounts Framework…………………………… 18 2.2 Area and Volume Accounts of Old Growth

Dipterocarp, 1988-1999…………………………….…. 24

2.3 Area and Volume Accounts of Second Growth Dipterocarp, 1988-1999………………………………... 26

2.4 Area Change by Forest Type…………………………. 28 2.5 Volume Change by Forest Type……………………… 29

2.6 Volume of harvested/Cut Rattan as Compared

to the stock, 1989-1999…………………………….…. 30

2.7 Monetary Valuation of Rattan Forest Resource at Current and Constant Prices, 1988-1999………………………………………………. 30

CHAPTER 3. LAND/SOIL RESOURCE

3.1 Physical Accounts Framework for the Land/Soil Resource,………………………………….. 51

3.2 Monetary Accounts Framework for the

Land/Soil Resource…………………………..……….. 52

3.3 Summary of Physical Asset Accounts for Forest, Agriculture, Built-up and Other Land Uses, 1988 and 1998………………………………………… 66

3.4 Comparison of Monetary Value of Forest, Agriculture and Built-up Use………………………… 67

xiii

Figure Number Title Page CHAPTER 4. MINERAL RESOURCE

4.1 Asset Account Framework for Mineral Resource… 93

4.2 Actual Nickel Extraction by RTNMC, 1988 – 1998………………………………………….. 96

4.3 Sand and Gravel Reserve and Extraction,

1990 –1999…………………………………………… 97

CHAPTER 5. WATER RESOURCE

5.1 Precipitation vs. Basin Recharge vs. Direct Run-off, 1987-1998……………………………………………… 116

5.2 Surface Water Physical Account (Net Basin Recharge vs. Withdrawal vs. Closing Stock), 1988-1998…….. 117

5.3 Surface Water Withdrawal, 1988-1998…………….. 117 5.4 Groundwater Physical Account, 1988-1998……….. 118 5.5 Groundwater Demand in 1988 an 1998..…………… 118

xiv

LIST OF APPENDIX TABLES Appendix Table Number Title Page CHAPTER 2. FOREST RESOURCE

2.1 Physical Area of Forest Lands by Type, Mainland Palawan, 1985 and 1992……………………………….. 37 2.2 Physical Area of Forest Lands by Type, Mainland

Palawan, 1986-1992…………………………………….. 37 2.3 Adjusted Physical Area of Forest Lands by Type,

Mainland Palawan, 1986 –1989………………………… 37 2.4 Average Bole Volume by Species in Dipterocarp Old

Growth Forest, Forest, Palawan………………………… 38

2.5 Average Bole Volume by Species in Dipterocarp Residual Forest, Palawan……………………………….. 39

2.6 Average Rattan Occurrence in Dipterocarp Old Growth Forest, Palawan……………………………. 40

2.7 Average Rattan Occurrence in Dipterocarp

Residual Forest, Palawan………………………………. 40

2.8 Total Volume of Timber Production, In Cubic Meters, 1988-1999………………………………………………… 41 2.9 Total Volume of Confiscated Timber, In Cubic Meters, 1988-1999………………………………………………… 41

2.10 Total Area Covered within ISF/CBFM Concessions

andAgro. Forestry, 1988 – 1999……………………….. 42

2.11 Total Area of Implementation of Conservation Efforts (Second Growth Forest), 1988 – 1999………………... 42 2.12 Total Area of Implementation of Conservation Efforts

(Mangrove Forest), 1989 – 1995………………………. 43

2.13 Total Area Damaged from Kaingin and Forest Fires, 1991-1999…………………………………………………. 43

2.14 Total Rattan Harvest Manifestation, 1988-1999………. 44

2.15 Total Volume of Confiscated Rattan, 1989-1995…….. 44

2.16 Rattan Resources Volume Accounts, 1988-1999

(In thousand lineal meters)……………………………… 45

xv

Appendix Table Number Title Page

2.17 Economic Accounts of Rattan at Current Prices 1988-1999, (in million pesos)……………………… 46

2.18 Computation for the Stumpage Values for Rattan Resources, 1988-1998…………………….. 47

CHAPTER 3. LAND/SOIL RESOURCE

3.1 Physical Area of Forest Lands by Type of Forest, Mainland Palawan, 1985-1998, in Hectares………………………………………… 81

3.2 Forest Destruction by Cause, Mainland Palawan, 1991 – 1998, in hectares…………….………… 82

3.3 Conversion of Forest Lands to Other Uses, Mainland Palawan, 1988-1997………….……. 82

3.4 Areas of Reforestation by Municipality, Mainland Palawan, 1987-1998, in hectares... 83

3.5 Logged Area, Palawan, In Hectares, 1988-1992……………………………….….….. 83

3.6 Land Values, Palawan, In Hectares,

1987-1998…………………………………..….. 83

3.7 Erosion Hazard Assessment, Tamlang Catchment, 1985……………………….….…... 84

3.8 Slope Distribution, by Class Interval, Palawan, in Hectares, 1985………………..….. 84

3.9 Retail Price of Fertilizers, Philippines, 1988-1998…………………………………..…… 84

3.10 Daily Wage Rate for Agricultural Plantation,

Philippines, 1986-1997……………………..….. 85

3.11 Physical Area of Agricultural lands by Type of Farm, Palawan, in Thousand Hectares, 1980 and 1988 to 1999…………………………. 85

3.12 Kaingin Areas, Palawan, in Hectares, 1991-1998………………………………….…….. 85

3.13 Land Conversion from Agricultural to Other Uses

by Municipality, Palawan, 1989-1998…………. 86

xvi

Appendix Table Number Title Page 3.14 Mangrove Area Converted to Fishpond, Palawan,

in hectares, 1995 to 1998…………………………… 86

3.15 Physical Area of Built-up Area, Palawan, 1988 to 1998, in hectares…………………………… 86

3.16 Estimated Zonal Values of Lands, by type of Land Use, Palawan, 1985……………………….. 86

CHAPTER 4. MINERAL RESOURCE 4.1 Nickel Reserve of Mining Companies, 1996………… 104

4.2 Volume of Nickel Reserve and Metal Content by Rio Tuba Nickel Mining Corporation, 1987 – 1996……… 105

4.3 Summary of Sand and Gravel Reserve on Selected Rivers in Palawan, 1999……………………….……… 106

4.4 Computed Unit Rent and Resource Rent of Nickel Resource, Palawan, 1988 – 1998……………….…… 106

4.5 Computed Unit Rent and Resource Rent of Sand and Gravel Resource, Palawan, 1990 – 1999……….…… 107

4.6 Market Price per Unit Volume, 1988 – 1999……….… 107 CHAPTER 5. WATER RESOURCE

5.1 Estimated Basin Recharge, 1987-1998 (MCM)…….. 124

5.2 Palawan Annual Rainfall Data, 1987-1998 (mm)…… 124 5.3 Palawan Hydrometric Network Mean River

Discharge, 1986-1989 (MCM)………………………… 124

5.4 Agricultural Water Uses from Surface Water in the Province of Palawan, 1988-1998 (MCM)…………… 125

. 5.5 Total Area Planted with Crops, in hectare, 1988-1998 125

5.6 Physical Accounts of Groundwater, 1980-1987 (MCM) 125

5.7 Water Demand from Groundwater, 1980-1996 (MCM) 126

5.8 Palawan Population Data, 1980-1998………………. 127

5.9 Number of Establishments, 1978-1999……………… 127

xvii

Appendix Table Number Title Page

5.10 Livestock and Poultry Water Demand from, Groundwater, 1988-1994 (MCM)…………………….. 128

5.11 Livestock and Poultry Population, Number of Heads, 1988-1998………………………………………………. 128

5.12 Groundwater Recharge Based from Rainfall, 1980-1998………………………………………………. 129

xviii

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Palawan is one of the remaining islands of the Philippine archipelago with a relatively well maintained environment. In order to ensure the preservation of the remaining forest areas, coral reefs and other fragile ecosystems as well as to promote the wise utilization of its natural resources, Republic Act No. 7611, otherwise known as the Strategic Environmental Plan (SEP) for Palawan Act, was adopted in June 1992 as the province’s framework for sustainable development. To achieve a balance between development and conservation, all programs and projects in Palawan were subsequently aligned with the goals and objectives of the SEP. Complementary policies were likewise issued by the provincial government in consonance with the plan.

The selection of Palawan as the pilot area for the institutionalization of the Philippine Economic-Environmental and Natural Resources Accounting (PEENRA) was then a welcome opportunity for the local government and the Palawan Council for Sustainable Development Staff (PCSDS), the policy-making body tasked with the operationalization of the SEP, to have at hand a system that can provide the basis for the formulation of the policies that will promote the rational utilization of its resources.

The provincial component of the UNDP-funded Environment and Natural Resources Accounting (ENRA) II Project called for the compilation of asset accounts of five major resources, namely, fishery, forest, land and soil, mineral and water. Based on the experience at the national level, asset accounts were estimated by technical working groups whose members came from 14 national agencies and offices of the Provincial Government of Palawan and the City Government of Puerto Princesa. Attempts were made to compute both the physical and monetary valuation of the resources. However, due to data limitations, both physical and monetary accounts were established only for fishery, land/soil, and mineral resources. For surface and ground water, mangrove forest and fishery resources, only the physical accounts were compiled.

A major objective of the project in Palawan was the institutionalization of the PEENRA system. As the lead implementing agency and in the light of its mandate under R.A. No.7611, the PCSDS assumed the responsibility of sustaining the activities. Immediately after the termination of the pilot testing in June 2001, the PCSDS integrated into its regular annual plan the updating of the asset accounts. The PEENRA system became a component of an Environmental Monitoring and Evaluation System which was developed to determine the status of the environment in support to the implementation of the SEP. Currently, preparations are underway to formalize the arrangements with the agencies of the national and local government to cover data gathering and actual compilation of the accounts. The recommendations made by the technical working groups will also be pursued.

The highlights of the results of the accounting exercise in Palawan are summarized in the following sections.

xix

Fishery Resource The resources covered in this accounting exercise are municipal and commercial marine fisheries. Because of constraints in the data, the compilation was limited to the estimation of the volume of depletion and an approximation of the sustainable yield levels based on the Fox Model.

The fishery sector contributed 22.8 percent and 20.6 percent to the gross provincial domestic product for Palawan in 1988 and 1994, respectively. Despite efforts to protect the numerous fishing grounds and long coastline of Palawan, the resource showed signs of depletion. A comparison of the trends in 1988 to 1998 reveals that fishing effort increased at a faster rate than fish catch. In fact, during this period, the volume of catch rose by 3.0 percent while fishing effort, based on the total horsepower of both municipal and commercial vessels, grew by 21.4 percent.

The maximum sustainable yield of 101,954 metric tons, that is, the biomass that can be caught without jeopardizing the fish stock of any species, was reached at an effort of 65,629 horsepower. During the earlier years of the accounting period, the volume of catch exceeded the rate of natural growth. Depletion level was pegged at a comparatively high 20,727 metric tons in 1988 but this went down to 1,413 metric tons in 1990. In the next four years (1992 to 1995), the extraction level was below the sustainable yield. During this period, the local government’s active law enforcement and concerted conservation and protection programs of different sectors were believed to have contributed to the recovery of the marine ecosystem from previous destructive fishing practices. However, starting 1996, the result showed that production activities had again put pressure on the resource as evidenced by the harvested volume being greater than the resource’s natural growth. From a depletion level of 2,639 metric tons in 1996, it rose to 23,607 metric tons in 1998. Based on the experiences in the compilation of the asset accounts and results of the accounting exercise, the technical working groups had drawn up recommendations to improve the data collection system and the actual consolidation of information from the offices of the different data producers. Initial policy recommendations were put forward to address certain issues that are being confronted in line with the management and utilization of these resources. Mechanisms to institutionalize the accounting were likewise identified.

xx

Forest Resource The forest provides both ecological and economic benefits. Palawan is one of the country’s provinces endowed with rich natural resources and the forest ecosystem is characterized by a highly diverse flora and fauna. Palawan’s forest land of 647,090 hectares accounts for 43 percent of Palawan’s total land area. Due to commercial logging, which was allowed until 1992, old growth forest area declined by 52 percent (175,990 hectares) from 1988 to 1999. From the closing stock of 339,208 hectares in 1988, total forest area decreased to 163,218 hectares in 1999. Similarly, the equivalent volume of old growth dipterocarp timber was depleted by 2.9 million cubic meters per year, reducing its 1988 timber closing stock of 61.1 million cubic meters to its 1999 stock of 29.4 million cubic meters. The monetary value for old growth forest fell during the accounting period by P 2.6 billion or P 233.9 million annually at current prices. At constant prices, the value shrunk from P 55.3 billion in 1988 to P 26.6 billion in 1999. The depletion that resulted from the changes in the physical stock of old growth forest averaged P 860 million per year or an annual decline of 1.6 percent. The 1988 closing stock of second growth forest area was 216,057 hectares and increased to 392,406 hectare in 1999, representing an 82 percent increase. Second growth dipterocarp timber volume increased by 25,042 thousand cubic meters from 1988 to 1999 with an average annual increase of 2,277 thousand cubic meters per year. Several factors contributed to the increase including the prevalence of reforestation and assisted natural regeneration activities and old growth forest being converted to second growth forest. The monetary value of second growth forest, likewise, showed an increasing trend with an annual average increment of P 4.1 billion at current prices and P 1.0 billion at constant prices. Mangrove forest plays a vital role in directly preserving the islands surrounding marine ecology. However, because of the conversion to fishpond and harvesting, vast tracts of mangrove areas were lost at a rate of 683.5 ha per year. The total mangrove stock declined at a rate of 88,091 cu. m. per year from its 1988 closing stock of 4.6 million cubic meters to 3.7 million cubic meters in 1999. Rattan stock in both old growth and second growth forest decreased at a rate of 4.5 million linear meters annually draining its 1988 closing stock of 746.0 million linear meters to 696.6 million linear meters in 1999. Because of the decrease in the volume of stock of rattan, the value of its closing stock at current prices increased from P 590.0 million in 1988 to P 1.1 billion in 1999. At 1985 prices, the real value declined from P 508.9 million in 1988 to P 470.0 million in 1999, recording an annual decline of 0.7 percent.

xxi

Land and Soil Resources Land and soil resources are among the most important natural resources because of their direct relationship to plants that in turn provide environmental benefits, food and livelihood. Thus, it is imperative to understand the nature and characteristics of these resources in order to manage and conserve them properly. Palawan is the largest province of the country with a land area of 1,489,630 hectares. In 1988, about 43.4 percent of its total land area was devoted to forest area, particularly in Mainland Palawan, 11.6 percent to agriculture use, and a negligible 0.5 percent to built-up use. Meanwhile, a large proportion of about 44.5 percent was classified as reproduction brush, grassland, water bodies and shallow coast including the forest areas in the island municipalities. From 1988 to 1998, forest area decreased from 647 thousand hectares valued at P 31.9 million to 612 thousand hectares valued at P 75.9 million in 1998. It declined at an average annual rate of 0.5 percent equivalent to around 3,545 hectares per year. Given the general increase in the prices of land, there was a substantial increase of P 44.0 million in the value of forest area. An average of 1,494 hectares per year of forest area was converted to different agricultural uses. Such change in land use was attributed to the deforestation caused by logging and conversion to kaingin and other non-forest uses. It also includes conversion of mangrove forest areas into fishpond.

In 1988, the total agricultural land was 172,945 hectares with a monetary value of P 1.7 billion which increased to 217,697 hectares in 1998 with a value of P 5.3 billion. Meanwhile, more than 600 hectares of lands devoted to agricultural uses was recorded as legally converted into built-up areas. It is however observed that this area is quite small considering the change in built-up area from 1988 to 1998 of 34,796 hectares (equivalent to P 84.1 billion). Unreported illegal land conversion from agriculture to other land uses without the approval of DAR is one of the reasons for the large area that is left unaccounted for. The change in soil quantity, expressed in terms of nutrient loss, serves as an indicator on the extent of soil degradation. The amount of soil eroded, on the other hand, is a measure of soil depletion. In 1988, a total of 11.8 million metric tons was eroded from forest and agricultural lands. By 1998, the volume was estimated at 13.9 million metric tons. Some portions of the eroded materials are deposited in waterways and farmland, while others may be dissolved in water as they are carried downstream. The volume of sediment due to erosion from forest and agricultural area grew from 8.1 million metric tons in 1988 to 9.6 million metric tons ten years hence. The annual average nutrient loss from sediments, expressed in fertilizer equivalent, from both forest and agricultural lands were 22,959 tons of nitrogen, 487 tons of phosphorous, and 3,542 tons of potassium. In sum, the estimated value of degradation amounted to P 111.2 million in 1988 and increased to P 253.8 million in 1998 for both forest and agricultural lands.

xxii

Mineral Resource Among the metallic mineral deposits mapped in the province are nickel, chromite, copper, mercury, antimony, lead, gold, manganese, uranium, pyrite and iron. Meanwhile, the non-metallic reserves are silica, limestone, pebbles, marble, coal, sand and gravel. Nickel, which is the only metallic metal currently being put into commercial production, was included in accounting for the resource.

The opening stock of nickel ore in 1988 was placed at 412.7 million metric tons and had an equivalent volume of about 5.8 million metric tons of metal. By 1998, the volume of nickel ore had declined to 407.5 metric tons with a corresponding metal content of 5.7 metric tons. The metal content slightly varied during the period from 1.41 percent to 1.43 percent. In sum, the total extracted ore during the accounting period of 3.7 million dry metric tons contained 52 thousand metric tons of nickel metal.

In monetary terms, Palawan’s nickel reserve, valued at P 272.6 billion in 1988, increased by 1.1 percent to P 304.7 billion in 1998. The variable market price of nickel was noted during the period. The highest market price was recorded in 1989 at P 68.25 per kilogram and the lowest was in 1993, pegged at P 27.07 per kilogram.

Based on a 1999 survey of 15 rivers in Mainland Palawan which are the major sources of sand and gravel aggregates, the reserve was placed at 5.4 million cubic meters. The volume extracted increased at an average of 12.7 percent per annum. From the 1990 extraction of 19 thousand metric tons, the volume rose to 71 thousand metric tons in 1999 with equivalent monetary values of P 66.6 million and P 629.4 million, respectively.

xxiii

Water Resource Palawan consists of 191 catchments, 31 of which are identified as major catchments. According to the Master Plan Study on Water Resources Management of the Philippines conducted by the National Water Resources Board (NWRB) in 1977, only 15 percent or 2,242 square kilometers of the 14,896 square kilometers total land area of Palawan has available groundwater. The population depends mainly on the groundwater for its domestic, commercial and industrial consumption. On the other hand, a large proportion of the surface water is being consumed by the agriculture sector. For this specific undertaking, both the surface and groundwater resources were covered. Results of the estimation of the physical accounts of surface water showed an increase in stock from 15,023.0 million cubic meters in 1988 to 45,642.5 million cubic meters in 1998. The increasing trend in the demand for surface water in agriculture is still very small compared to the basin recharge. Thus, the available stock for surface water adds potential for the agricultural development of the province. The groundwater stock depends on the recharge from rainfall. The province experienced the lowest recharge in 1991 due to lower amount of rainfall particularly in the southern part of the mainland. The study showed an increase in abstraction of groundwater for domestic, commercial and industrial purposes from 24.4 million cubic meters in 1988 to 37.7 million cubic meters in 1998. The increase in abstraction may be attributed to the rapid increase in population brought about by migration.

Palawan Marine Fishery Resource

Environmental and Natural Resources Accounting

MARINE FISHERY RESOURCE 1.1. INTRODUCTION 1. Palawan is an archipelago of 1,780 islands and islets with a coastline of about 2,000 kilometers. It has an estimated water body of 49,408 square kilometers, coral reefs of 9,800 square kilometers (excluding Tubbataha and Kalayaan) and a mangrove forest of 46,445 hectares (JAFTA, 1992).

2. The province has numerous coves and bays with rich fishing grounds. About 64,400 fishers, majority of whom are migrants coming from Cebu, Iloilo and other provinces ply these waters. Palawan contributes roughly 40 percent to the total fishery production of the Philippines (BAS, 1998). Commercial and municipal fisheries registered an average production of 94,070 metric tons annually from 1988 to 1998 (Figure 1.1). Vessels classified under municipal fishery represented 77 percent of the total fishing boats. Similarly, about two thirds of the total catch in 1998 was contributed by municipal fishery. It is not surprising therefore that fish is the principal source of protein for the Palaweños whose per capita food requirement for fish is estimated at 30.66 kilos per annum (MHS, 1982).

Figure 1.1 Catch by Commercial and Municipal Fishery Industry,

Palawan, 1983 to 1998 (In Metric Tons)

10,000

20,000

30,000

40,000

50,000

60,000

70,000

80,000

90,000

1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998

Cat

ch (i

n m

etric

tons

)

CommercialMunicipal

3. In 1995, about 75 percent (NSO, 1995) of the total population resided in the coastal zone whose sources of livelihood were derived from the coastal/marine resources. Majority of the local residents engaged in municipal fishing, however some of them resorted to deep-sea fishing in order to increase production. One of the factors that influenced small fishers to go beyond the municipal waters was the declining catch.

Palawan Marine Fishery Resource 2

Environmental and Natural Resources Accounting

4. Human activities have been contributory to the deterioration of the coral reef, sea grass beds and mangrove forest that serve as shelter and nursery of spawning and juvenile fish. The problems besetting the fishery resource are also rooted to the destructive activities in the terrestrial area that cause siltation and sedimentation in the coastal areas. Moreover, the use of harmful fishing methods, such as trawl and dynamite fishing, and obnoxious substances like sodium cyanide, put pressure on the resource. Meanwhile, the mangrove forest in Southern Palawan has been destroyed through illegal mangrove tree debarking and conversion of mangrove forest into fishpond. The coral reefs are also deteriorating as disclosed by some researches. For example, out of 75 sites surveyed in 1997 to 2000 by the Palawan Council for Sustainable Development Staff (PCSDS) and Non-Government Organizations (NGOs) in Puerto Princesa City, Aborlan, Narra, Espanola, and Busuanga, only 12 percent were classified under excellent condition, that is, having a coral cover of at least 75 percent.

5. To address these problems and issues and to formulate appropriate plans and policies in accordance with the concept of sustainable development, comprehensive information on the status of the fishery sector is needed by planners and policy makers. It is for these reasons that accounting of the resource was pursued under the Environment and Natural Resources Accounting (ENRA) II Project. 1.2. CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

1.2.1 Scope and Coverage

6. The fishery resource accounts cover cultivated and non-cultivated fish stock and other aquatic animals. The former includes the stock of fish and other aquatic animals in fishponds and farms while the latter are found in the ocean and the inland and coastal waters. The study however is confined to non-cultivated fish stocks and due to data limitations, it covers only marine fishery resource for the period 1988 to 1998.

1.2.2 Framework of the Asset Account 7. The SEEA framework was used in the accounting of the resource both for the physical and monetary accounts. Below is the conceptual framework operationalized to come up with the fishery resource accounts for the Province of Palawan.

Figure 1.2 Asset Accounts Framework for Fishery Resource

Palawan Marine Fishery Resource 3

Environmental and Natural Resources Accounting

OPENING STOCK

Changes due to economic activity Depletion Total Catch Sustainable Yield Other Accumulation +/- Conversion of fish stocks to economic control Other Volume Changes due to natural or multiple causes + Natural growth - Natural mortality +/- Net migration - Mortality due to natural disasters or due to the

destruction of natural habitats Changes in Stocks Revaluation* CLOSING STOCK

*For monetary valuation only

Fish Stocks

8. The opening and closing stocks characterize the volume of the asset at a given point in time. Ideally, the stock is measured in terms of the biomass at the beginning and end of the accounting period.

Changes in Stock

9. Change in the volume of stock is affected by natural loss, fishing activity and recruitment. Fishing is an extraction activity resulting to reduction of stock. The level of fish catch that is beyond its natural growth occurring at a given point in time is considered as depletion. It occurs when total catch exceeds sustainable yield.

Other Accumulation

10. The positive or negative conversion of fish stocks to economic control is accounted as other accumulation.

Other Volume Changes

11. The variables classified under other volume changes may be due to natural or multiple causes. It consists of natural growth as additional stock and natural mortality as reduction to the stock. Mortality due to natural disasters or destruction of natural habitat is also a reduction to the stock. Meanwhile, net migration is either addition or reduction to the stock.

12. Due to data constraints, the accounting of the fishery resource was limited to the framework discussing the changes due to economic activity particularly on the depletion of the marine fishery resources. The methods used in the exercise is just an alternative approach to account for the resource rent based on the level of depletion, considering that depletion is only one of the changes in the balance sheet. The physical and monetary values of depleted commercial and municipal fish catch were presented as an initial output for the fishery resource accounting.

Palawan Marine Fishery Resource 4

Environmental and Natural Resources Accounting

1.3. OPERATIONALIZING THE FRAMEWORK

1.3.1. Sources of Data 13. The basic data requirements of the account using the Fox model are volume of catch and the fishing effort expressed in terms of horsepower. The Bureau of Agricultural Statistics (BAS) provided the data for total fish catch and producers’ price based on their surveys covering the period 1988 to 1998. Data on catch from 1983 to 1987 were retrieved from the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR) Statistical Profile. The total number of fishing boats and their corresponding gross tonnage and engine horsepower for commercial and municipal fishery were derived from the records of fishing vessel operators when they apply for a license from the office of the Philippine Coast Guard, BFAR and MARINA. Since these are available in raw form, processing of data on horsepower and gross tonnage from individual licenses issued to fishing operators was undertaken under the project1.

14. Gathered data were only restricted to a period of fifteen years covering 1983 to 1998. Data on total fish production, measured in metric tons, were gathered from landing centers and were classified into commercial and municipal fishing. Commercial fishing uses boats that are more than three gross tons while municipal fishing uses boats of three gross tons and below.

1.3.2 Estimation Methodology

Fish Stock

15. The Palawan Technical Working Group (PTWG) attempted to compute for the physical asset accounts of the fishery resource using the System of Integrated Economic and Environmental Accounting (SEEA) framework. However, results of stock assessment surveys of several reef areas of Palawan conducted independently by BFAR, PCSDS and NGOs were not sufficient to represent the stock of the province’s numerous fishing grounds.

Fish Catch

16. One of the data needed to derive variables on fishing effort, sustainable yield and depletion is the fish catch. Data on fish captured from commercial and municipal fishing were gathered focusing only on marine fishes. Fishery products such as shrimps, prawns and other invertebrates were excluded in the resource accounting. To show the status of Palawan’s fishery resource in terms of Maximum Sustainable Yield (MSY) for fishing, a series of data of at least fifteen years was compiled. An undercoverage of 20 percent was applied to compute for the total fish production (NSCB, 1994). It represents the assumed unrecorded fish catch in different landing sites not monitored by the survey conducted by BAS.

Fishing Effort

17. At the outset, the working group tried to estimate the stock based on the assumption that a coral reef yields an average 15.6 tons/km2/year (White, et. al.,

1 Processing of data from the files of individual operators was contracted in order to estimate the

horsepower of fishing vessels.

Palawan Marine Fishery Resource 5

Environmental and Natural Resources Accounting

1998). However, this method was not deemed acceptable to the UNSD consultant since it only accounted for the growth for a particular year and did not provide the initial stock. It was further recommended that ICLARM should be consulted on the establishment of the baseline data and development of a model that can be adopted for the regular updating of the accounts.

18. Finally, the group adopted the Fox Model the data requirements of which are fish catch and total fishing effort (expressed in horsepower) to be able to come up with an estimated catch per unit effort (CPUE), sustainable yield and depletion. Absence of published data on the number of fishing vessels, gears used and number of fishers prompted the processing of raw data on fishing effort from individual records of fishing boat operators from boat licensing offices, namely, MARINA, Philippine Coast Guard and BFAR.

19. Initial results of the data processing from the records of the afore-mentioned agencies showed a big leap in the horsepower from 1991 to 1992 and 1997 to 1998. One of the possible causes of the erratic trend was the failure of some fishing operators to register their vessels for the year although their operation was uninterrupted. In 1992, the recording system may have been affected by the transfer of responsibilities on boat licensing from the Philippine Coast Guard and MARINA. Missing records were also noted. There were some municipalities with zero registration which is considered impossible and therefore erroneous. Meanwhile, intensified law enforcement activities of national agencies and local task forces in 1998 was believed to have been instrumental to the increase in the number of registered fishing boats.

20. In view of these observations, the PTWG reviewed the raw data processed by the contractor and conducted a rapid appraisal of the economic life span of fishing boats. As a result, duplicate entries were cancelled and the records corrected. A minimum period of eight years was applied to a fishing boat starting from the year it was built. Based on the adjusted data, the total horsepower of commercial and municipal fishing vessels was derived. It is noted however that this computed horsepower is underestimated. The equivalent fishing effort of the fishing gear and the fishers were not covered because of the absence of an inventory of gears used while there were no data on the number of fishers by type of employment, that is, on the number of full-time, part-time time and occasional fishers.

Sustainable Yield

21. Sustainable yield was estimated using the Fox Model. The equation below was used (Philippine Asset Accounts, 1998):

Y = E exp (a + b E)

where: Y = catch or yield from the resource E = fishing effort per unit time a = constant b = regression coefficient

22. The regression coefficient was determined by establishing the relationship between the time series data on fish catch and the estimated fishing effort.

Depletion

Palawan Marine Fishery Resource 6

Environmental and Natural Resources Accounting

23. To compute for depletion, total actual catch was deducted from the sustainable yield. If the catch exceeds the sustainable yield, depletion then occurs. To value the cost of resource depletion, expressed as net rent, the net price method was used. Net rent is the value of the output per unit of measurement after deducting the expenses incurred in extracting the resource.

The equation used is as follows:

Depletion = Actual Catch less Sustainable Catch Net rent = Net price per unit x Depletion

1.4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

1.4.1. Share of the Fishery Sector to GPDP

24. Fishery is a major sector of the economy of Palawan. Estimates of the Gross Provincial Domestic Product (GPDP) in 1988 showed that agriculture, fishery and forestry accounted for about 54.2 percent of the provincial economy with fishery contributing 22.8 percent (Table 1.1). By 1994, the share of the fishery sector was slightly smaller at 20.6 percent but it still had contributed the second largest share to the total GPDP, next to agricultural crops.

Table 1.1. Gross Provincial Domestic Product Accounts, Palawan, 1988 and 1994 (In Million Pesos)

At Constant 1985 Prices Percent Sector 1988 1994 1988 1994

Agriculture, Fishery and Forestry

1,603.9

1,907.7

54.2

49.9

Agricultural Crops 602.0 866.0 20.4 22.7 Livestock and Poultry 166.2 253.3 5.6 6.6 Fishery 673.8 784.9 22.8 20.6 Forestry 161.8 3.4 5.0 0.1 Industry 459.7 636.9 15.6 16.7 Services 891.6 1274.4 30.2 33.4 G P D P 2,955.2 3819.0 100.0 100.0 Source: Development of the Gross Provincial Domestic Product (GPDP) Accounts for the Province of Palawan, NSCB, Provincial Government of Palawan, PCSDS, 1998 1.4.2 Fish Catch and Fishing Effort

25. During the entire 11-year accounting period, municipal fishery comprised the bulk of the total fish production (Table 1.2). On the average, catch of municipal fishers represented 74 percent of the total while commercial fishery accounted for the remaining 26 percent. Both municipal and commercial fishery showed an increasing trend in terms of catch.

26. Results of the comparative analysis of fish catch vis-à-vis fishing effort or the CPUE (Figure 1.3) also showed that the rate of increase in fishing effort was more than that of the fish catch. Total catch rose by 3.0 percent from 1988 to 1998 while fishing effort increased by about 21.4 percent.

Palawan Marine Fishery Resource 7

Environmental and Natural Resources Accounting

Table 1.2. Estimated Volume of Catch of Marine Fishery Resource,

Palawan, 1988 - 1998

Fish Catch

Year Municipal Fishery (in metric ton)

Commercial Fishery

(in metric tons)

Total (in metric

tons) 1988 54,284 28,622 82,907

1989 56,264 32,456 88,721

1990 69,349 20,348 89,698

1991 73,624 21,066 94,690

1992 67,136 15,380 82,517

1993 68,108 25,426 93,534

1994 73,556 24,076 97,632

1995 74,580 20,579 95,159

1996 73,256 20,890 94,146

1997 81,731 26,082 107,813

1998 81,605 26,356 107,960 Source: BAS Central

Figure 1.3. Total Catch vis-à-vis Total Fishing Effort

-

20,000

40,000

60,000

80,000

100,000

120,000

1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998

Tota

l Cat

ch (i

n m

etric

tons

)

-

20,000

40,000

60,000

80,000

100,000

120,000

Fish

ing

effo

rt (in

hor

sepo

wer

)

Total CatchFishing Effort (Hp)

1.4.3 Sustainable Yield and Depletion

27. Extraction of marine fish and utilization of the fishery resource in general cannot be left unregulated. However, in order to have a sound basis for managing and regulating the extraction of the resource, fish stock, sustainable yield and levels of depletion, if any, of the resource should be determined. Because attempts in this study to establish the sustainable yield was faced with the difficulty of meeting the data requirements of the SEEA framework, an approximation was arrived at using the Fox Model.

28. Table 1.3 shows the estimated sustainable yield and depletion of the marine fishery resource after combining the catch and effort of municipal and commercial fisheries. At the start of the accounting period in 1988, depletion was observed and

Palawan Marine Fishery Resource 8

Environmental and Natural Resources Accounting

continued until 1991 but at a decreasing rate; from 20,727 metric tons, the level of depletion went down to 1,413 metric tons. Apparently, efforts by law enforcement agencies to curb destructive fishing methods were becoming effective. During this time, the government introduced interventions to put a stop or at least minimize harmful fishing practices and restrain over-fishing. The local government organized the Bantay Dagat, an inter-agency task force that was formed to enhance the monitoring of the coastal areas and went further to apprehending violators of fishery regulations and other environmental laws. From 1992 until 1995, there was no recorded depletion of the marine fishery resource.

29. However, in 1996, depletion of the marine fishery was again evident. Starting at a volume of 2,639 metric tons, it dramatically rose to 20,153 metric tons in 1997 and went further up to 23,607 metric tons in the following year. It is believed that initial headway reached in combating illegal fishing activities and destruction of the marine ecosystems during the early 90’s may have not been sustained.

30. Figure 1.4 presents the Sustainable Yield – Effort Curve with Maximum Sustainable Yield estimated at 101,954 metric tons and effort at 65,629 horsepower.

Table 1.3. Estimated Marine Fishery Resource Depletion, Palawan, 1988-1998

Year Total Catch Fishing

Effort (Hp) Sustainable

Yield Depletion

1988 82,907 19,958 62,180 20,727 1989 88,721 25,462 72,946 15,774 1990 89,698 34,415 86,023 3,675 1991 94,690 41,695 93,277 1,413 1992 82,517 47,120 97,050 - 1993 93,534 59,256 101,441 - 1994 97,632 67,391 101,918 - 1995 95,159 89,816 96,517 - 1996 94,146 101,047 91,507 2,639 1997 107,813 108,593 87,659 20,153 1998 107,960 114,715 84,354 23,607

Figure 1.4. Sustainable Yield - Effort Curve for Marine Fishery Resource, 1988 – 1998

Palawan Marine Fishery Resource 9

Environmental and Natural Resources Accounting

50,000

60,000

70,000

80,000

90,000

100,000

110,000

- 20,000 40,000 60,000 80,000 100,000 120,000 140,000

Fishing Effort (in horsepower)

Sust

aina

ble

Yiel

d (in

met

ric to

n)

1988

1989 1990

19911992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

Estimated Maximum Sustainable Yield = 101,954 metric tons

Estimated Maximum Fishing Effort = 65,629 horsepower 1.5. RECOMMENDATIONS 31. There are indications that the fishery resource of Palawan is now facing threats. Based on the initial findings of the study, the volume of depletion of marine fishery resource is rising at an increasing rate. However, to have a more solid basis for evaluating the condition of the resource and in the formulation of the appropriate policy interventions, the SEEA framework should be fully operationalized. Foremost is the need to satisfy the data needs of the framework. Along this line, follow-on activities are recommended in order to meet the requirements of the fishery resource accounting, namely:

a. Resource assessment should be conducted to be able to establish the

fish stock. b. Close monitoring of fishing activities and regular collection of data

should be strengthened. Among the data that should be compiled are: (a) fish catch by species; (b) number of fishermen and terms of employment, that is, whether full-time, part time, or occasional; (c) number of fishing boats with corresponding horsepower; and (d) inventory of fishing gears.

c. The prevailing price of fishery products by species should be gathered

as well as cost of production to facilitate monetary valuation. d. Installation of Municipal Fishery Licensing System to keep a record of

operating fishing vessels. This will help in determining the pressure to the coastal area as a result of fishing. It will also provide baseline information that can be subsequently used for regulatory and revenue purposes.

Palawan Marine Fishery Resource 10

Environmental and Natural Resources Accounting

e. Strengthen collaboration with the provincial offices of national agencies and the municipal offices in the compilation of data that they generate through locally initiated surveys and in the exercise of their regulatory functions. These data should be incorporated into their regular reports.

f. Conduct of studies to gather a more comprehensive data on cultivated

and non-cultivated fish stock for both marine and fresh water bodies 32. Moreover, it is emphasized that the economy of Palawan is still hinged on the agricultural sector, in particular, crop farming and fishery, which are the population’s major sources of livelihood. While this study is focused on the fishery resource, it should not be overlooked that most fishers also cultivate small farm lots to augment their income. Further, because of the topography of the province, its coastal areas and marine resources are especially vulnerable to adverse environmental activities in the terrestrial areas. Aside from the destruction of the mangrove and marine ecosystems that have direct impact on the resource, activities in the terrestrial areas (e.g., lowland and upland farming) also affect the coastal areas. As such, depletion of the resource is not only the effect of harmful fishing practices but may also be the result of equally harmful farming techniques. Fishing and farming should therefore be addressed through parallel interventions. It is imperative that both sectors be afforded immediate attention in terms of policy and program formulation. 33. Meanwhile, efforts to mitigate the problems on illegal fishing call for stricter implementation of fishery laws and related environmental laws primarily to protect and conserve the coastal marine ecosystem and its natural resources. Formulation of municipal and barangay ordinances to support national policies is likewise recommended.

Palawan Marine Fishery Resource 11

Environmental and Natural Resources Accounting

ACRONYMS

BAS Bureau of Agricultural Statistics

BFAR Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources

CPUE Catch Per Unit Effort

GT Gross Tonnage

Hp Horsepower

ICLARM International Center for Living Aquatic Resources Management

MARINA Maritime Industry Authority

MSY Maximum Sustainable Yield

MT Metric Tons

NGO Non-Government Organizations

PCSDS Palawan Council for Sustainable Development Staff

PTWG Provincial Technical Working Group Members

SEEA System of Integrated Economic and Environmental Accounting

UNSD United Nations Statistics Division

JAFTA Japan Forest Technical Association

Palawan Marine Fishery Resource 12

Environmental and Natural Resources Accounting

DEFINITION OF TERMS

Depletion is the extraction of fishery resources beyond the rate of natural growth, measured as a positive difference between catch and sustainable yield. It occurs when the total catch exceeds the natural growth.

Commercial Fishing is fishing for commercial purposes in sea waters with the use

of fishing boats of more than three gross tons. Fishing Boat refers to the watercraft used for catching and transporting of

fish resources from seawaters. Fish Catch refers to the volume of fish landed by commercial and

municipal fishery industry. Fishing is the catching, gathering and culturing of fish, crustaceans,

mollusks, and all other aquatic animals and plants in the sea or in inland waters. It includes the catching of fish and aquatic animals like turtles; the gathering of clams, snails, shells and seaweeds; and the culturing of fish and oysters. Sport fishing or small sale fishing pursued as a hobby is excluded.

Fishing Effort refers to manpower, machine power and technology employed

in harvesting fishery resources yielding to catch per unit effort. It is measured in terms of horsepower.

Fishing Gears are equipment used in catching fish with or without the use of

boats. Marine Fishery refers to the fishing activity at the seawaters outside of the

coastal line.

Municipal Fishing is characterized by the use of simple gear and fishing boats some of which are non-motorized and with a capacity of three and less than three gross tonnage.

Horsepower is the work done at the rate of 550 foot-pounds per second and

it is equivalent to 745.7 watts

Palawan Marine Fishery Resource 13

Environmental and Natural Resources Accounting

REFERENCES Bureau of Agriculture Statistics. Production Fishery Production Statistics, Production

Statistics, BAS. 1988 – 1993. BAS, Quezon City. Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources. 1997 Philippine Fisheries Profile. BFAR.

Quezon City. Ilarina, Vivian. Compilation of Resource Accounts (Selected Case Studies) Fishery

Resources. International Workshop on Environmental and Economic Accounting. September 2000. Manila, Philippines.

Ministry of Human Settlements. Town Planning Guidelines and Standard, Economic

Sector, 1982. National Statistics Office. 1995 Census of Population (Palawan). Palawan Integrated Area Development Project, Phase II Final Report. Volume 2-

Production Component Annexes. February 1990. Philippine Asset Accounts. ENRA Report No. 2. May 1998. NSCB. Japan Forest Technical Association (JAFTA). Forest Register (Palawan). Information

System Development Project for the Management of Tropical Forest. 1992. White, Allan, et al. The Value of Philippine Coastal Resources: Why Protection and

Management are Critical. 1998. Coastal Resource Management Project. DENR and United States Agency for International Development. Cebu City, Philippines.

Palawan Marine Fishery Resource 14

Palawan Forest Resource

Environmental and Natural Resources Accounting

FOREST RESOURCE 2.1 INTRODUCTION 1. Palawan is situated in the southwest part of the Philippine Islands chain. Palawan stands as the country's largest province with its 1.5 million hectares land area. Tall mountain ranges bisect the province into east and west coast. The east coast has narrow beaches and a swampy shoreline, backed by plains and short valleys. The west coast is more rugged, with mountains rising up near the sea, and narrow lowlands. Palawan, often intriguingly described as "The Last Frontier" and "Paradise Lost", is home to vast rainforests, underground rivers and cave systems, mangrove swamps, and rare species of flora and fauna found only in the Philippines. Palawan’s forest area of 647,090 ha accounts for 43 percent of its total land area (NAMRIA, 1985 and JAFTA, 1992). 2. The objective of this study is to account for the physical and monetary stock of the forest resources from 1988 to 1999 and to determine the factors that contribute to the changes. Ultimately it aims to come up with relevant recommendations in the proper management of the resource.

3. Palawan’s forests are classified into four different types, namely, dipterocarps, submarginal, mossy and mangrove forest. Dipterocarp forests are further classified as either old growth or second growth. Old growth dipterocarp forests are virgin forests with no traces of commercial logging, while second growth dipterocarp forests are those with traces of logging (NSCB, 1998). The dipterocarp forest is the principal Indo-Malayan tropical rainforest formation. It is one of the world’s three main tropical rainforests in addition to the tropical American and African rainforests. Several layers of vegetation and a multiplicity of tree species characterize these tropical rainforests. The dipterocarp forest is not a pure stand of tree species belonging to the family Dipterocarpaceae but rather a mix forest consisting of species of various families with the dipterocarp as dominant component. 4. Philippine dipterocarps are mostly medium to large sized trees, unbranched to a considerable height and usually attain a height of 40 to 65 meters in diameter at breast height (dbh) or diameter above buttress (dab) of 60 to 150 centimeters. A few unusually large trees have been found to attain a dab as large as 30 cm, their boles are generally straight and regular (Whitford, 1911; Tamesis and Aguilar, 1951). In terms of economic importance, the family Dipterocarpaceae produces the greatest bulk of commercial wood in the country sold worldwide under the trade name “Philippine Mahogany”. Dipterocarp timber constitutes the bulk of our country’s log exports and wood for domestic building construction and infrastructure development (NSCB, 1998). 5. Mangroves are coastal trees or shrubs that are adapted to estuarine or even saline environments. The term mangrove refers to the individual plants, whereas mangal refers to the whole community or association dominated by these plants. Mangroves have characteristic features that allow them to live in marine waters (Calumpong and Meñez, 1996).

Palawan Forest Resource 16

Environmental and Natural Resources Accounting

6. Mangroves minimize soil erosion and pollution of seawater. Its extensive air root system traps eroded soil and industrial pollutants especially during strong rains; aids in reclaiming considerable land area, shelterbelt against tidal waves, typhoons and strong winds; wildlife habitat; increase fish and shellfish productivity; provides alternative wood supply, and industrial inputs such as resin for plywood, adhesive manufacture, fuelwood and high grade charcoal, tanning for dyeing hide into leather, viscose rayon for textile fabric manufacture; livestock feed supplement, medicine and wine, vinegar and thatching materials from nipa (Soriano and Fortes, 1987). It is also for these reasons that mangrove forests are drastically exploited. To address possible loss of mangrove genetic diversity or a much worse scenario of the entire mangrove forest area of the province being wiped out, Palawan’s mangrove area has been declared a Mangrove Swamp Forest Reserve on December 29, 1981. 7. Rattan is a climbing palm which has a versatile stem of high economic value. It is one of the most important non-timber forest products of Palawan. It is used in the manufacture of fine handicrafts, furniture and furniture components, binding materials, fish traps, hammocks, sleeping mats, carpet beaters, hats, walking sticks, tool handles and others. Palawan is a major source of rattan poles for furniture centers like Manila, Iloilo and Cebu. It is a major livelihood source for poor and indigenous communities who are tapped by most rattan permittees for cane gathering and processing. 8. Among the many non-timber forest resources, rattan is being prioritized in this accounting effort in view of its worsening state. Unlike bamboo, rattan is not so prolific. Since rattan is co-terminus with dipterocarp forests, rattan is subject to the damages caused by logging of its tree hosts. 2.2 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

2.2.1. Scope and Coverage

9. The system of forest resource accounting calls for the compilation of asset accounts for area (in hectare) and volume of standing trees (in cubic meter) and non-timber forest products. However, for this study, the accounting is limited to the asset accounts of dipterocarp forest (old growth and secondary growth), mangrove forest, and rattan. These resources were included in the accounting process because of their economic and ecological significance and in consideration of the availability of data.

2.2.2. Framework for the Asset Account

10. The forest accounts, in physical and in monetary terms, adopted the format presented on the next page. The opening stock represents the stock of resources at the beginning of the accounting period. Several factors account for the changes in stock including changes due to economic activities, other accumulation, and other volume changes representing the changes due to non-economic factors. Other volume changes include the statistical discrepancy equivalent to the difference between the computed closing stock (based on the framework’s identified factors) and the opening stock of the succeeding year. The closing stock for a year is equal to the opening stock of the succeeding year.

Palawan Forest Resource 17

Environmental and Natural Resources Accounting

Figure 2.1. Asset Accounts Framework

OPENING STOCK

Changes due to economic activity Assisted regeneration Legal Logging Unauthorized cutting Damage from logging

Other Accumulation

Forest Conversion

Other Volume Changes Stand growth Mortality Forest fires Natural Disasters

Changes in stock

CLOSING STOCK

11. Changes due to economic activity refer to human production activities as they affect the stock of resources. Assisted regeneration is caused by human intervention in regenerating natural forests such as plantations and reforestation activities. Legal logging refers to the commercial logging done by concessionaires from 1988-1992 when commercial logging was still allowed in the province. Legal logging data from 1993 onwards account for harvest manifestations from areas with known Certificate of Stewardship Contracts (CSC) as proof of right in the management of the awarded forest area. The item unauthorized cutting, on the other hand, accounts for illegally extracted resources as manifested by confiscated forestry products during apprehension. Damage from logging accounts for forest resource damages, which resulted in the actual conduct of the logging activity.

12. The item other accumulation covers forest conversions which mainly refers to clearing of forest to convert it to other uses such as for residential or industrial purposes. Under other volume changes, additions to the stock include natural stand growth and regeneration while reductions to the forest cover are mortality, forest fires and natural disasters.

2.3 OPERATIONALIZING THE FRAMEWORK

2.3.1. Sources of Data Physical Accounts 13. The base information for forest area was lifted from the 1992 JAFTA LandSat Thematic Mapper and 1985 aerial photographs from NAMRIA, covering mainland Palawan. Stock volume was projected using information available from the RP-German Forest Resource Inventory Project (FRIP). The project generated data on the inventory of standing volume, forest regeneration and minor forest products from national agencies and LGUs.

Palawan Forest Resource 18

Environmental and Natural Resources Accounting

14. For dipterocarp forests, data for depletion due to legal logging and unauthorized harvesting were taken from the Provincial Environment and Natural Resources Office (PENRO) and Community Environment and Natural Resources Offices (CENRO) of the DENR, Economic Intelligence and Investigation Bureau (EIIB), and Bantay Palawan, a multi-sectoral task force that conducts apprehension of illegal loggers. 15. For mangrove forests, data came from DENR-PENRO, CENROs, and Municipal Planning and Development Offices (MPDOs). Rattan data were lifted from the RP-German FRIP and records of the DENR-PENRO, Bantay Palawan and EIIB.

Monetary Accounts

16. Parameters used in the computation of stumpage value for rattan were supplied by the National Statistics Office, National Statistical Coordination Board and Pio Bote’s 1990 study on stumpage value for dipterocarp forest.

2.3.2. Estimation Methodology 17. Physical asset accounts for old and second growth dipterocarp forest and mangrove consisted of area and volume accounts while accounts for rattan were limited to volume only. On the other hand, the study came up with the monetary valuation only for dipterocarp forest and rattan. There was no available information on the stumpage value of mangrove forest.

Physical Asset Accounts, Area

a. Old Growth Dipterocarp Forest

18. In the compilation of the physical asset accounts, the forest stock in area terms were projections from the 1985 NAMRIA aerial photographs and 1992 JAFTA satellite imagery covering mainland Palawan only. Legal logging in old growth forests from 1988-1992 were still covered by Timber License Agreements before the implementation of the total commercial log ban in the entire province.

19. Other changes under other volume changes represent the statistical discrepancy (S.D.) or the unaccounted factors in the changes in area. It is derived as the reported closing area during the year, taken from the official sources, less the computed closing area, derived by summing up the opening area, changes due to economic activity, changes due to other accumulation and the identified other volume changes.

b. Second Growth Dipterocarp Forest

20. Changes due to economic activity include assisted regeneration/plantation or reforestation, the accounted legal logging and logging damage. Assisted regeneration comprised the area covered by those forest areas with Certificate of Stewardship Contracts (CSC) such as Integrated Social Forestry (ISF) Program, Community Based-Forest Management Agreements (CBFMA), Industrial Tree Plantation (ITP) and agro-forestry projects. Legal logging area was derived from the total area covered within ISF/CBFM

Palawan Forest Resource 19

Environmental and Natural Resources Accounting

concessions, ITP and agro-forestry areas times 80 percent1. The estimated damage due to logging was placed at 15 percent of logged area (legal and illegal logging) in old growth forests during the previous year. Other accumulation includes data covered by old growth forest converted to second growth forest and other non-forest land use and areas devoted/converted to kaingin or upland farming. The area converted from old growth to second growth is equal to the area logged in old growth forest in the previous year less 15 percent for log landings, roads and skidding/yarding trails. Other volume changes account for area covered by forest fires and statistical discrepancy (S.D.) or the unaccounted factors in the changes in area.

c. Mangrove Forest

21. Mangrove forest area was likewise derived from the same geometric projections as that of the dipterocarp forest. Changes due to economic activity includes plantation and reforestation efforts, which are treated as an addition to stock, and unauthorized mangrove harvesting, and charcoal making, which are treated as reduction to the stock. Mangrove forest conversions to fishpond development were the activities that contributed to area deductions under other accumulation and as such also treated as reduction to the stock. Statistical discrepancy (S.D.) was likewise accounted for under other volume changes.

d. Rattan

22. No separate area accounts for rattan were compiled since rattan thrives in the same area as that of dipterocarp forest.

Physical Asset Accounts, Volume

a. Old Growth Dipterocarp Forest 23. Opening volume was derived from area projections multiplied by harvestable volume of 180.2 cu. m. per hectare computed from the FRIP. Legal and unauthorized logging were regarded as depletion as adopted from actual data generated from EIIB, DENR-PENRO and CENRO’s monthly accomplishment reports. Other changes (S.D.) were computed using the same procedure as in the area accounts.

b. Second Growth Dipterocarp Forest

24. Opening and closing volume were likewise derived from the area projections in second growth dipterocarp following the same sources and multiplying the computed area by 142 cu.m. per hectare, harvestable volume for second growth dipterocarp forest based on the results of the FRIP.

25. Damage from logging, kaingin, and forest fires were treated as depletion from stock while old growth conversion to second growth was accounted as addition. All derivations were obtained using the same assumed 142 cu.m. per hectare harvestable volume. Meanwhile, stand growth under other volume changes was computed by multiplying the opening area with the annual growth rate of 4.735 cu. m. per hectare based on the study of Uriarte and Virtucio in 1988.

1 It is assumed that the actual area logged is 80 percent while 20 percent will remain as second growth forest.

Palawan Forest Resource 20

Environmental and Natural Resources Accounting

c. Mangrove Forest

26. Volume determination was based on a special study conducted by the PCSDS; the results of which showed that the average volume was 128.93 cu. m. mangrove timber per hectare. The mangrove timber volume was multiplied to the opening and closing area based on the 1985 NAMRIA aerial photographs and 1992 JAFTA LandSat TM.

27. Unauthorized harvesting data were lifted from DENR-CENRO, Roxas. Stand growth for other volume changes was based on young growth of 1.1 cu. m. per hectare per year derived from the study entitled Physical Forest Resources of Palawan by Carandang (1994).

d. Rattan

28. Data on rattan include the average rattan occurrence in both old growth and secondary growth forests. Separate estimates were made for rattan poles with diameters of less than two centimeters (< 2 cm) and that for poles greater than two centimeters (> 2 cm). The opening volume was computed based on the average rattan occurrence of 1,060.7 lineal meter and 946.3 lineal meter per hectare of < 2 cm poles in old growth and residual forests, and 393.2 lineal meter and 224.1 lineal meter for pole > 2 cm in the same types of forests, respectively, as indicated in the FRIP.