PAIRED-COMPARISON AND TRIANGLE SENSORY METHODS COMPARED FOR USE IN PRODUCT IMPROVEMENT

-

Upload

charlene-james -

Category

Documents

-

view

222 -

download

0

Transcript of PAIRED-COMPARISON AND TRIANGLE SENSORY METHODS COMPARED FOR USE IN PRODUCT IMPROVEMENT

PAIRED-COMPARISON AND TRIANGLE SENSORY METHODS COMPARED FOR USE IN PRODUCT IMPROVEMENT

CHARLENE JAMES

General Nutrition Corporation, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15222l

Accepted for Publication October 24, 1985

ABSTRACT

m e use of the paired-comparison and triangle difference sensory techniques were compared in results obtained in the evaluation of a product reformulation. Both techniques were found to be statistically similar in sensitivity for discrimination, but not in preference between a presently marketed and a pro- posed new product formulation, when conducted as outlined in this study. It was shown that a no-difference option and two like samples should be incorporated into a paired-comparison test. A complete balanced order of sample presentation should be used in a triangle test. Either technique could be a useful tool in "in- house" benchtop reformulation of products.

INTRODUCTION

The proper use and evaluation of sensory evaluation testing in the product development decision making process is as important as other factors in a pro- duct's success in the market place (Civille 1978). Within product reformulation or in brand comparisons of two products, preference testing often is conducted because information on consumer preference is desired. However, if a preference test alone is conducted, researchers are making the assumption that the consumer panelists can actually distinguish between the two samples when differences between them may not be readily apparent. More validity could be placed on these preference judgments if it is first established that judges can dif- ferentiate between samples evaluated (Amerine et al. 1965). Therefore, several investigators have combined a standard discrimination test with preference (Woodward and Schucany 1977; Moskowitz 1983).

'Research was conducted at the Department of Home Economics, University of Arkansas through the support of the Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station, Fayetteville, Arkansas.

Journal of Food Quality 9 (1986) 175-IU. AN Rights Reserved. 0 Copyright 1986 by Food & Nutrition Press, Inc., Westpon, Connecticut. 175

176 CHARLENE JAMES

Discrimination tests that are most frequently employed by U.S. food com- panies are the pairedcomparison and triangle techniques (Brandt and Arnold 1977). The pairedcomparison and the multiplecomparison tests have been recommended over the triangle test because they are more economical to con- duct on an aliquot-for-aliquot basis, require less panel time, tasting, and laboratory preparation (Gridgeman 1955; Hogue and Briant 1957; Dawson et al. 1963; Larmond 1977). However, a comparison of the results obtained from the pairedcomparison and triangle techniques has led to contradictory results, which makes it difficult to select one method over the other for use in product development. Byer and Abrams (1953) found that results obtained from a pairedcomparison test reflected discrimination of higher significance than did those obtained from a triangle test in testing quinnone and dextrose aqueous solutions. However, the panelists were not evaluating the same factor in both tests. In the pairedcomparison test, panelists were asked to indicate the intensity of the known solution. However, in the triangle test, they were asked first to determine difference and then intensity of the samples. Filipello (1956) also showed that the triangle design was not as sensitive as the paired-comparison, but this was in the testing of thresholds of simple taste solutions and not complex food systems. Gridgeman (1970) showed that pairedcomparison results more sharply distinguished preferential differences between two treatments, but com- pared this to a more psychologically complex two-stage triangle test. This in- volved the presentation of four samples at once in which panelists were asked to separate samples into two like-pairs.

Other researchers have found comparable results between the two techniques. Dawson and Dochterman (1951) asked panelists to first indicate difference, then preference in the evaluation of two treatments of chocolate fudge. These researchers found no difference in precision between the two techniques as in- dicated by the percent of correct responses. Gridgeman (1955) also did not find either test to be superior in terms of panel sensitivity in the evaluation of primary flavors, tomato juice or ground beef. Hogue and Briant (1957) compared a multiplecomparison test with the triangle-test in the evaluation of green beans and squash and found that the triangle method was more precise because it in- dicated differences that the multiple comparison did not show.

Discrepancies among the reports on the comparison of these two techniques appear to be related to the type of sample being tested or the design of the ex- periments. Therefore, it was desirable to determine whether or not the paired- comparison and triangle tests were equivalent in precision and sensitivity in their use of "in-house " benchtop reformulation research of a complex food product for first difference and then preference evaluations.

PAIRED-COMPARISON AND TRIANGLE SENSORY 177

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Testing Conditions

Two treatments of both commercial whole- and speardill pickles were evalu- ated for difference and preference by both the pairedcomparison and triangle techniques. The wholes and spears were evaluated in separate testing sessions. The treatments were a presently marketed formulation and a proposed change in formulation. For both sensory techniques, the panelists were first asked to discriminate between or among the samples and then were asked to indicate their sample preference. The pairedcomparison and triangle techniques were evaluated in separate testing sessions. Any students, faculty, or staff personnel from the University of Arkansas who liked dill pickles and were available on the day of testing were obtained in either mid-morning or mid-afternoon to par- ticipate as consumer laboratory panelists. These panelists were seated in fully lighted isolated booths.

All pickle samples were coded with 3digit random numbers and served at am- bient temperature on white plates. The whole pickles were cut to remove the ends and then cut width-wise and served in quarters. The spears were cut width- wise and served in halves. A panelist did not receive a quarter or half from the sample pickle sample. Panelists were instructed to clear their palate with an un- salted cracker and water between the two tests that were conducted in a session, which gave the panelists about a 3 min rest between sample pairs or triads tested.

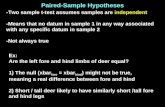

Paired-Comparison Design

Each panelist received two pairedcomparison tests at one session (Fig. 1). Four possible pair orders were presented, which included the present formula- tion (P) and the new formulation (N), N and P, P and P, and N and N. Sample presentation order was a counter-balanced complete block design. Each panelist received a pair of odd samples P and N (or N and P) and a pair of like samples P and P (or N and N) in one session. A total of 48 panelists participated in both the whole and spear pickle tests; therefore, results for each pickle sample are based on a total of 96 judgments.

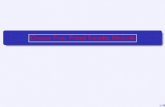

Triangle Test Design

Each panelist evaluated two triangle tests at one session (Fig. 2). Six possible triad orders were presented, which included P-N-N, N-P-N, N-N-P, N-P-P, P-N-P, and P-P-N. Half of the panelists were presented with P as the odd sample in their first triangle test and N as the odd sample in the second triangle test in a

I78 CHARLENE JAMES

KOSHER DILL PICKLES

You will be served two d i l l p i c k l e s twice. They may o r may not be the name products . numbers a r e l i s t e d below.

You w i l l n o t i c e t h a t the products a r e coded and t h a t these

Take s e v e r a l b i t e s of t h e sample on the l e f t f i r s t . Wait about 60 seconds and take a dr ink of water. Then t a s t e t h e second product i n the same way. You may go back and t r y the p i c k l e s aga in i f you wish.

Is there a d i f f e r e n c e between samples and 1 Y e s - No I f you found a d i f f e r e n c e , which sample do you p r e f e r i n ( c i r c l e which appl ies )

color : e i t h e r

tex ture : e i t h e r

t a s t e : e i t h e r

Other c h a r a c t e r i s t i c s : (p lease write in)

P lease c l e a r your p a l a t e with the cracker and water provided and r a i s e hand f o r second sample.

FIG. 1. PAIRED-COMPARISON SCORE CARD USED TO EVALUATE PICKLES FOR DIFFERENCE AND PREFERENCE

KOSHER DILL PICKLES

You w i l l be served 2 sets of d i l l p i c k l e samples. d i l l p i c k l e samples a r e i d e n t i c a l , t h e t h i r d is d i f f e r e n t .

1.

In each set, 2 of the

Take s e v e r a l b i t e s of each sample i n t h e order ind ica ted and i d e n t i f y the - ODD sample. (Please save some of the sample f o r ques t ions below).

Code Check Odd Sample

2. Which sample do you p r e f e r ? (check one) - d u p l i c a t e samples odd sample e i t h e r sample n e i t h e r sample

- - 3 . you prefer red one sample over t h e o ther , check one o r more reasons below

a s t o why you prefer red t h a t sample:

Prefer red Dill P i c k l e has a:

Better co lor - B e t t e r tex ture - B e t t e r t a s t e Other c h a r a c t e r i x ( p 1 e a s e w r i t e in ) :

Thank you f o r your p a r t i c i p a t i o n .

P lease c l e a r your p a l a t e with t h e cracker and water provided and push your t r a y through f o r your second and l a s t set of samples.

FIG. 2. TRIANGLE SCORE CARD USED TO EVALUATE PICKLES FOR DIFFERENCE AND PREFERENCE

PAIRED-COMPARISON AND TRIANGLE SENSORY 179

session. Odd sample presentation was reversed for the other half of the panelists. Sample presentation and test design was a balanced-incomplete block design. Fifty-four panelists participated in the tests for the whole pickles, which resulted in 108 total judgments for each sample. Only 32 panelists participated in the tests for the pickle spears, because of a limited supply of sample. Therefore, spear results are based on a total of 64 judgments.

Analyses

The number of correct judgments in both techniques were analyzed for signifi- cant difference using the expanded tables or the calculation given by Roessler ef al. (1978). Preference scores were tabulated and analyzed only for those samples in which the panelists correctly identified the difference between the samples.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Total correct discrimination evaluations of the pickles as analyzed statistically indicated that both the pairedcomparison and triangle methods resulted in similar sensitivity (Table 1). The panelists could not discriminate between the present and the new whole-pickle formulations by either sensory technique, and did discriminate between the two spear-pickle formulation by both senosry techniques. The difference in level of statistical significance shown between the two techniques for the spear pickles should not be equated with the magnitude of difference between the two samples or the two sensory techniques. Level of significance only indicated the likelihood that the difference is real and not due to chance. The significant correct judgments that indicated that differences existed should be interpreted with caution because the typical consumer still may not notice differences, as did the somewhat limited number of "in-house " panelists who participated. However, the nodifference result obtained with the whole pickles probably can be used as an indication that consumers will not find any difference because "in-house " panelists are usually more discriminate (ASTM 1968; Stone and Side1 1978). If the latter is the case, the probability that a non- discriminating consumer will choose one product should be the same as the pro- bability that the consumer will choose another product unless some other factor than sensory (such as price, advertising, etc.) has an influence on their decision (Woodward and Schucany 1977).

In the pairedcomparison tests, panelists could discriminate (P 5 0.001) be- tween the two treatments when presented with two unlike samples (Table 1). However, when two duplicate samples were presented, panelists could not cor- rectly determine that there was no difference. Therefore, it is suggested that if a paired-comparison method is chosen over the triangle method for testing product differences, each panelist should be presented with two paired-comparisons , two

180 CHARLENE JAMES

Table 1 . Number of correct judgmentshotal number of judgments that in- dicated if there was a difference between a present (P) and a new (N) dill pickle product

Dill Pickle Product Wholea Spears

Paired-Comparison

PN or NP 30/48*** 41/48***

PP or NN 15/48 18/48

Total 53/96 59/96**

TrianKle

PPN, NPP. or PNP 22/54 17/32**

NNP. P", or NF" 22/54 12/32

Total 44/108 29/64*

like samples and two different samples, as outlined in the above procedure. The total correct judgments from both paired comparison tests should then be taken into account before drawing any conclusions as to whether the differences detected were real. This would give more confidence in the results. Dawson and Dochterman (1951) found that both the pairedcomparison and triangle tests gave the same results, but the triangle test gave more confidence in the results because of the opportunity to eliminate judges who could not identify duplicate samples. To give equal confidence in the results based on this criterion, the pairedcomparison results in this study included those judges who could not identify duplicate samples by adding these judgments to the total number of judgments (Table 1).

In the triangle spear-pickle tests, results were influenced by which treatment was present as the duplicate or odd sample. Panelists could discriminate (F'< 0.02) between the spear-pickle samples only when the duplicate samples were the present formulation and the odd sample was the new formulation (Table 1). In the tabulation of preference responses of all the panelists who could correctly discriminate between samples in the triangle test, it was shown that the present formulation was preferred in taste more often than the new formulation (Table 2). Therefore, differences between treatments may have been more apparent when the preferred sample was presented as the duplicate samples, but not when it was presented as the odd sample. Other researchers (Amerine er al. 1965) also have shown that panelists preferred the sample presented as the duplicate

PAIRED-COMPARISON AND TRIANGLE SENSORY 181

Table 2. Percent of preference judgmentsa between a present and new dill spear-pickle product

S p e a r P i c k l e P r o d u c t P r e s e n t N e w E i t h e r

Pa i red-Compar ison

C o l o r

T e x t u r e

2 2 29 4 9

3 2 41 2 1

T a s t e 4 1 54 5

T r i a n g l e

Color 1 0 0 9 0

T e x t u r e 4 1 7 52

T a s t e 55 10 35

aBased on number of preference judgments/total number of correct difference judgments, which was 41 for the paired<omparison and 29 for the triangle tests.

samples when a preference judgment was included in a triangle difference test. For this reason, both samples should appear as duplicate and odd samples an equal number of times to balance the contrast effect of odd or duplicate sample bias on panelists’ evaluations.

Preference judgment percentages for color, texture, and taste of the spear pickles obtained in both sensory tests were not in complete agreement. Of the 41 correct difference judgments in the pairedamparison test (Table l), there did not appear to be a preference for either the present or new formulation in any sensory characteristic evaluated (Table 2). Since panelists did find a significant difference (PI 0.001) between these two treatments (Table I ) , these further non- significant preference evaluations indicate that one group of consumer panelists preferred one treatment and another group equally preferred the other. In the triangle test, the majority of the panelists had a preference in taste only for the present formulation over the new formulation. The whole-pickle preference results were not considered because there was not a significant difference in total number of correct difference judgments by either sensory technique (Table 1).

182 CHARLENE JAMES

CONCLUSIONS

Results obtained from the paired-comparison and triangle techniques appeared to indicate that the two techniques are statistically similar in sensitivity for discrimination, but not for preference between products if the tests are con- ducted as outlined in this study. If the pairedcomparison preference technique is used, it is suggested that a nodifference option and two like samples be incor- porated into the test. If the trianglelpreference technique is used, a complete balanced order of sample presentation should be used. Either technique with ap- proximately 50 in-house, nonexpert employees could be a useful tool in the in- itial phases of product reformulation.

REFERENCES

AMERINE, M.A., PANGBORN, R.M. and ROESSLER, E.B. 1965. Prin- ciples of Sensory Evaluation of Food, p. 374, 444. Academic Press, New York.

ASTM. 1968. Manual of Sensory Testing Methods, pp. 16-18, ASTM Special Technical Publication 434, American Society for Testing and Materials, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

BRANDT, F.I. and ARNOLD, R.G. 1977. Sensory tests in food product devel- opment. Food Prod. Develop. 11(8), 56.

BYER, A.J. and ABRAMS, D. 1953. A comparison of the triangular and two- sample taste-test methods. Food Technol. 7, 185-187.

CIVILLE, G.V. 1978. Case studies demonstrating the role of sensory evaluation in product development. Food Technol. 32(1 l), 59-60.

DAWSON, E.H., BROGDON, J.L. and MCMANUS, S. 1963. Sensory testing of differences in tastes. I. Methods. Food Technol. 17(9), 45-48, 51.

DAWSON, E.H. and DOCHTERMAN, E.F. 1951. A comparison of sensory methods of measuring differences in food qualities. Food Technol. $79-81.

FILIPELLO, F. 1956. A critical comparison of the two-sample and triangular binomial designs. Food Red. 21, 235-241.

GRIDGEMAN, N.T. 1955. Taste comparisons-two or three? Food Technol.

GRIDGEMAN, N.T. 1970. A reexamination of the-two stage triangle test for the perception of sensory differences. J. Food Sci. 35, 87-91.

HOGUE, D.V. and BRIANT, A.M. 1957. Determining flavor differences in crops treated with pesticides. I. A comparison of a triangle and a multiple comparison method. Food Res. 22, 351-357.

9, 148-150.

PAIRED-COMPARISON AND TRIANGLE SENSORY 183

LARMOND, E. 1982. Laboratory Methods for Sensory Evaluation of Food, p. 23, Public. 1637, Communications Branch, Agricultural Canada, Ottawa KIA OC7

MOSKOWITZ, H.R. 1983. Product Testing and Sensory Evaluation of Foodr, pp. 308-326, Food and Nutrition Press, Westport, Connecticut.

ROESSLER, E.B., PANGBORN, R.M., SIDEL, J.L. and STONE, H. 1978. Expanded statistical tables for estimating significance in paired-preference, paireddifference, duo-trio, and triangle tests. J. Food Sci. 43, 940-943,947.

STONE, H. and SIDEL, J.L. 1978. Computing exact probabilities in sensory discrimination tests. J. Food Sci. 43, 1028-1029.

WOODWARD, W.A. and SCHUCANY, W.R. 1977. Combination of a pre- ference pattern with the triangle taste test. Biometrics 33, 31-39.