P r e p a r i n g T h e G r o u n d F o r A ‘ N e w E c o n o mi ......C o mmu ni t y – I nc l u...

Transcript of P r e p a r i n g T h e G r o u n d F o r A ‘ N e w E c o n o mi ......C o mmu ni t y – I nc l u...

Living An Emergent Life

Preparing The Ground For A

‘New Economic System’ In Piracanga

Mar Michelle Häusler

MA Economics for Transition Schumacher College

University of Plymouth

2016

1

ABSTRACT

This dissertation explores the preparation of the ground for a new economic

system for Piracanga, an eco-village and intentional community in Bahia, Brazil.

It is my account of the journey that brought me to this exact place in time to

witness and be part of the preparation and unfolding of a new economic system,

for the community and beyond.

Inspired in new economic theory, and working live as a ‘social practitioner’, I

share interactions through conversations, accounts and personal stories for the

unravelling of what wants to be brought to the surface and transformed. It is a

personal account, interwoven with stories and conversations with eco-village

and Inkiri community members. The piece attempts to bring the economic story

of Piracanga to life, whilst exploring deeper themes that emerged throughout the

study, such as power and control, inclusion and exclusion and the shadow within

a community.

2

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

With my deepest gratitude to Schumacher College, Jonathan Dawson and the

bursary fund for making it possible for me to embark on the Economics for

Transition Masters program.

I also feel a profound appreciation for Patricia Shaw who has guided me through

this journey and encouraged me to open my eyes to a new way of living. It has

been a life transforming experience beyond what words can describe or put

justice to, as at times it felt so uncertain and yet this was the biggest lesson for

me.

An enquire such as this would have been impossible without the cooperation and

openness of the Inkiri community and everyone living in Piracanga. I am

especially grateful to Angelina for trusting me, opening her home and the

community for me to ‘work the ground’ for the new economic system. I am

indebted to the people living in Piracanga for making the exploration a fun as

well as enlightening task, of whom many supported and took a keen interest in

my work. I am especially grateful to Diego and Humberto for the lovely team we

formed and many hours spent together during my time in the Inkiri community.

With deep gratitude to Ragi for the long reflective conversations we shared.

With profound appreciation to everyone who has been part of my journey during

the past years and at Schumacher College, for the contribution to my life and to

bringing this piece of work into being. A special thank you to Rachel for

dedicating herself selflessly in supporting the process of materialising this piece

of work and Brenda for keeping our home in Dartington warm during my

unplanned journey.

Deepest gratitude to my dearest brother, Marc, for being in my life and walking

this journey with me – you have been a greater support than you can fathom. To

my parents, for giving me the space to live my life, that at moments you do not

understand nor agree with, and my dear sister Nadia, thank you for being you.

3

TABEL OF CONTENT

ABSTRACT 2

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 3

INTRODUCTION 5

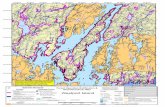

EXPLAINING THE LANDSCAPE 8 Piracanga Landscape 8 Locating Myself Within The Inkiri Community 12

MY STORY 14 Arrival In Piracanga 15 Coming To Piracanga – A Level Deeper… 16 The Finance Years 18 Spiral To This Moment 20

ENGAGING WITH THE LITERATURE 21 Economics And Complementary Currencies 22 Eco-Villages And The Transition Movement 24 Working As A ‘Social Practitioner’ 24

METHODOLOGY 27 Conceptual Approach 27 Practical Applications 28 Thesis Unfolding Process 29

THE ECONOMIC STORY 31 My Personal Process Of Writing The Account 32 A Brief Account Of The Economic Story 35 The Four Waves 36 Wave 1 37 Wave 2 40 Wave 3 41 Fourth Wave – A Beginning… 42

CROSS-CUTTING THEMES 43 Community – Inclusion And Exclusion 43 Power And Control 47 Freedom – Working Hours 49 Connection To The Local Community 50 The Shadow - Intentional Communities Vs. Transition Towns 52

EXPLORING OUR INNER WORLD 55 Workshops 55 The Lecture 59

CONCLUSION 61

REFERENCES 64

APPENDICES 68 Questionnaire 68

4

What shape waits in the seed of you to grow and spread its branches

against a future sky?

(David Whyte)

INTRODUCTION

Writing this title, ‘Preparing The Ground For A ‘New Economic System’ In

Piracanga’ brings back memories of a conversation I had with Angelina , the 1

leader of the Inkiri community in Brazil’s Piracanga where the thesis project was

based. Angelina was telling me about teachings she had channelled from the

1 In telling this story, I have used a combination of real and fictitious names, without indicating which is which. I have used real names where people wished, with their consent, especially in situations where their position would have made it impossible to provide any real anonymity. Elsewhere I have elected to use pseudonyms in order to provide some measure of confidentiality, although I am aware that the closeness of community life makes true anonymity virtually impossible.

5

natives that used to inhabit the land the Inkiri community now stands on. They

had talked to her about the way we plant seeds nowadays; about how we often

dig a hole whilst thinking about other things, placing the seed into the soil and

covering it up without presence or focus.

This process of bringing a new life to this earth is sacred, she told me. It is life

bearing, giving us nutrients and nourishment for our existence. What the Indians

had revealed to Angelina is that this is one of the most sacred connections that

exists between the natural world and ourselves.

I found the teachings they had passed on fascinating. The Indians said, for

example, that when planting, we should give our full attention to this sacred

process. The first step is for us to open the packet of seeds, whether they were

store-bought or collected and dried, and to hold these seeds in our hands,

honouring them as bearers of new life. Each small seed, they pointed out, has the

ability to grow into a plant or tree and to bear countless produce for our benefit.

The next step, they suggested, was for us to place each seed in our mouths to be

covered with our saliva. This saliva is the first water that the seed will receive.

Most significantly, it contains our information and, as all of life is connection and

our saliva bears aspects of our humanity, through this act, our information is

then passed on to the seed. The seed can integrate this information and be

shaped by it.

The final part of the process is to place the seed into the earth, our mother earth,

and cover it with soil. The soil should be well prepared to receive the seed,

providing the best possible conditions for it to thrive. Having had contact with

our saliva, the plant knows our needs and can develop the nutrients that we

humans most require.

As I write the title of my dissertation, this image is radiating profoundly within

me. I can see the Inkiri community and the land named Piracanga. The seed

6

embodies the dream that the Inkiri community carry of a new economic system

for their community and for the world. The saliva symbolises the knowledge and

experience that each person brings to nourish the seed; their shared dream. The

first contact with water is the essence that is brought from each individual to the

seed for the collective dream to grow. The soil is Piracanga itself and all the

potential contained within; grounded, waiting patiently for the right conditions

to bring forth new life.

The dissertation is the preparation of the soil in which the seed will be planted.

The Inkiri community has a dream to change the world. Starting with a new

economic system for their community, they carry a vision of their own currency,

a bank and a whole new way of organising their local economy that will change

the way people interact with each other. From there, they hope, these new ways

of doing can spread to other places, creating change on a far broader scale.

This document contains my account of how the people of Inkiri are preparing the

ground to plant the seed of a new economic system. My role in this process, along

with the process itself, is explored in the following chapters. I arrived in

Piracanga following a series of most improbable synchronicities; synchronicities

of the kind I have come, if not to expect, then at least, not to be too surprised by.

This is also part of the story.

This process of creation is still very much alive and continuing. The thesis will

therefore reach no conclusion nor paint a final picture of what is happening in

Piracanga. This document contains a snapshot of the current moment in time,

sharing insights with the reader about what has taken place so far and what is

emerging. The process is constantly evolving so new narratives are developing.

The more we ask questions and inquire, the deeper we go and the more that is

revealed. It is an unfolding that is infinite and will continue beyond my time here

at Piracanga.

7

Even After All this time The Sun never says to the Earth,

"You owe me." Look What happens With a love like that,

It lights the whole sky.

(Hafez)

EXPLAINING THE LANDSCAPE

Piracanga Landscape

Piracanga is the name given to an area of land purchased by a group of eight

people, approximately 13 years ago, that had travelled from various locations in

Europe. This group intended to create some kind of intentional community based

on a shared vision of a new way of living. Piracanga, an isolated beachside

settlement, was named after the river Piracanga that ran alongside the

purchased land.

8

This original group of eight knew each other prior to their arrival in Piracanga.

Their agreed leader was Angelina, who had had visions of this land in a dream

years before. From Portugal, Angelina had run a holistic centre previously and

was experienced in leadership and the dynamics of groups.

The land was divided into plots and collectively termed ‘the eco-village’, with

each person building a house on their land allocation. The original agreement

was to build on 10% of Piracanga and keeping the remaining 90% as natural

habitat. For many of this original group, the plan was to live only part of the year

in Piracanga, where they could be in retreat and have focused space for spiritual

practice.

As part of this establishment phase, a holistic centre named “Centro Universal do

Desenvolvimento do Ser” [CUDS] was set up. Translated into English as the

“Universal Centre for the Development of the Being”, CUDS, was invested in by

seven members. Over time, the ownership stake of the original seven members

have been bought out by the growing Inkiri community, who are slowly

acquiring full ownership of the Centre. In August 2016, the community signed a

lease to rent the buildings of CUDS for 10 years; it is currently being rebranded

Centro Inkiri.

Since its inception, CUDS has been the primary source of income generated

within Piracanga itself. Over time, CUDS has grown into a recognised and

respected centre of learning and healing, attended not only by Brazilians but also

by international visitors seeking a place for relaxation, healing and

self-development. Originally Angelina was the only teacher at the Centre, leading

courses in aura reading and dreams interpretation. This has since expanded,

with many more teachers and a vast amount of different courses being taught.

As the numbers of people at Piracanga grew, many disagreements arose over

vision and how this should manifest at a practical level. Over time, a subset of

people formally formed a distinct community within the broader Piracanga

9

eco-village. Termed ‘the community’ and more recently renamed ‘the Inkiri

community’, this initial group comprised 12 members village who shared a

dream for a new world. With Angelina as their leader, and sharing a spiritual

path, the group sought to collaborate on projects that would inspire humanity to

be happy, free and live their dreams.

Herein referred to as Inkiri, their mission is based on seven pillars, imagined as

sunrays of manifestation: self-knowledge; community; children; nature; arts;

creation and nourishment. Each of these pillars is a work-in-progress, with

ongoing work to clarify and deepen understanding of each. Each pillar has a

mission statement attached to it.

1. Self-knowledge - Search the truth inside of you

2. Community – Living in union serving the dream

3. Children – Creating conditions so that the essence can be manifested

4. Environment – To take care of the earth as our mother

5. Arts – To create beauty in everyday existence

6. Creation – Power of creating things with enthusiasm to transform our

reality

7. Nourishment – To nourish the body in harmony with the earth

Running alongside this process, there is an interwoven story involving the

Brazilian humanitarian and spiritual teacher Sri Prem Baba. Based in Alto

Paraiso, Sri Prem Baba has a large and rapidly growing community of followers,

both Brazilian and international. Sri Prem Baba connects back to a number of

different lineages including the Hindi tradition (and physically to a specific

ashram in Northern India), to western psychology and to the Shamanic Tradition

of the Forest. In some respects, his work is in constant evolution; in others, the

essence remains the same. At the very heart is the movement from fear to trust;

from fear to love. Seen from the Eastern perspective, the three pillars of the work

are: jnana yoga (self knowledge), a key feature of which is investigative or

analytic meditation; bhakti yoga (devotion) and karma yoga (service). The

10

specific healing and spiritual practices he uses have their roots in all of these

traditions.

Over time, Angelina and some others within Inkiri have connected with Sri Prem

Baba, formally becoming his disciples, and a decision has been made to

intentionally connect Inkiri to his teachings. At a practical level, Inkiri has

decided to adopt the core values espoused by Sri Prem Baba: honesty,

self-responsibility, kindness, dedication, service and beauty. I am also a follower

of Sri Prem Baba and it is through this connection that I became involved at

Piracanga.

There were no formal plans in the evolution of Piracanga. Everything that has

taken place over the years has been an unfolding of one event leading to another.

Based on size and its projects, Piracanga is considered one of the most successful

communities and eco-villages in Brazil. In fewer than 13 years, it has become a

reference internationally, with its model based on spirituality and harmony with

nature.

There are currently approximately 250 people living in Piracanga, 200 of which

are part of the eco-village and 50 of which make up Inkiri. The holistic centre,

renamed Centro Inkiri, CUDS, can accommodate up to 120 guests at a time, with

further accommodation options for another 100 people. The basis for CUDS has

continued to evolve: at one point it was solely focused on expansion and profit

maximisation, whereas now it is influenced by the work of Sri Prem Baba. There

are also many Inkiri projects that form the backbone of the community and

Piracanga. The education and holistic development projects include the school

for the children, Aura reading school, the Nature school, the University, the

Service school and Re-birthing school. Alongside these there are the projects that

are important for the functioning of Inkiris’ daily activities, such as the transport

project, the permaculture and recycling centre, the restaurant, the food shop, the

communications team and economics group. Piracanga is also known for its

creativity, brought to life through the cultural space, circus and clown project,

11

music school and ‘Acai do Mar’ a space for afternoon celebrations and

community cooking.

Locating Myself Within The Inkiri Community

Upon arrival, I struggled both to locate myself within the community and to

identify the role I was to play there. I was based specifically within Inkiri, yet I

was not officially part of Inkiri, yet I was included immediately, participating in

community meetings from my first day. Reading Allan Kaplan inspired me to see

my role as a ‘social practitioner’. His words resonated strongly within me: “Only

by entering into intimate relationship with the situation (thereby also becoming

part of the situation) will we be graced with enabling the situation to speak to

us” (2002). Beyond this, it was up to me to work out what this would actually

mean.

I became aware that while I could help them tell their story, I was also becoming

part of it; research moving beyond the mechanistic view of subject-object to one

of interrelating. Again, Kaplan’s words resonated.

There is no spurious objectivity here. The organism is already changing in response to a new relationship, which is the relationship between the practitioner and itself. Practitioners ‘interfere’ with precisely what they are researching. They become part of the system through the new set of relationships which is generated (Kaplan 2002).

What was apparent was that I needed to work from the inside out, by becoming

part of the organism, which in this case was the Inkiri community. My role was

not to impose any concepts, ideas and models but rather engage with what was

alive; to facilitate what wanted to be born. Shotter has described this same

phenomenon as ‘witness-thinking’, that our interaction affects the flow process

from within, “this kind of responsive understanding only becomes available to us

in our relations with living forms when we enter into dialogically structured

relations with them” (2005). Consequently I became ‘a part’ of the Inkiri

12

community, my role a subjective one of working from within the community to

enable what wants to be born to take form.

As I take on the dual role of observer-participant, I am both neutral and involved.

It is important for me to be aware of my social conditioning, past influences,

habits and judgements. Presence, awareness and spontaneity, as Patricia Shaw

(2006) emphasises, are key to this work; to be able to both be present to the

situation and observe our own processes, whilst acting spontaneously.

Self-knowledge is fundamental to the capacity to observe our own projections

and how we relate to situations as they arise. “Good acting comes when you have

rehearsed the play, but in the moment of performance you are spontaneously

recreating the play on the basis of the experience from the rehearsals” (Shaw

2006). Putting aside the “conscious controlling of the actions” and listening to

your body, opening the space for “being present” and “acting spontaneously”.

The account I provide in these pages contains much about my own personal

process, additional but inextricably interwoven with what it reveals about the

Inkiri community and what is happening there. I will admit to a certain level of

discomfort with this, not so much because of the information it provides others

about my own inner life, but more out of fear of appearing self-centred. Yet I am

realising that this inner journey is a vital and integral part of the greater

unfolding and learning. The evolution and growth takes place within as much as

it does on the outside: as I evolve, so too does my perspective and my capacity to

hold space for what wants to materialise. To hold this space of tension long

enough for the new to emerge, without the need to impose a solution or to

resolve the situation. The importance lies neither in the objects nor the outcomes

of a situation, (the ‘tangible’ results we observe), but in the space between these.

In Shotter’s words, “…Thus the outcomes of our inquiries are not to be measured

in terms of their end points – what they result in producing – but in terms of

what we learn along the way, in the course of their unfolding movement” (2012).

The invisible that can neither be seen nor touched, that is ever evolving. So here I

13

attempt to provide an account of these moments, leaving it for others to interpret

and to perceive, as it is not the outcomes that I believe matter as much as the

process from which others may draw inspiration from.

14

The Way It Is

There is a thread you follow. It goes among things that change.

But it doesn’t change. People wonder about what you are pursuing.

You have to explain about the thread. But it is hard for others to see.

While you hold it you can’t get lost. Tragedies happen; people get hurt or die;

and you suffer and get old. Nothing you do can stop time’s unfolding.

You don’t ever let go of the thread.”

(William Stafford)

15

MY STORY

What is it that brought me so unexpectedly to this place? How did I end up

helping to give birth to a new economic system in an isolated beachside

community in Brazil, hours from an airport, where the internet connection dies

each time it rains, when just a few short years before I had been a high flyer in

the world of international finance? Tom Anderson, a “wonderer and worrier”,

similar to myself, talks about turning away from the path that is not right

(Shotter, 2009) and this, as well as anything, sums up what happened to me.

And, as Anderson describes, having done this, alternatives, including most

unexpected ones, pop up almost by themselves…

Arrival In Piracanga

In the words of Angelina, leader of Inkiri, “Piracanga was ready for you and you

were ready for us”. It was a coming together that fit perfectly from the start. The

idea of a new economic system had been fermenting within Inkiri for some

months prior to my arrival yet no direct steps had been taken as a block existed

in the form of an influential community member, Lisa, who was not yet open to

the idea. Several times in the previous year she had wanted to resign from her

financial-related position within CUDS, but Angelina had convinced her to stay.

Three days before my arrival she had repeated her request but this time,

Angelina had felt the time was right so had supported her to do so. Through her

departure, the area of economy within Inkiri opened up and new possibilities

could be more freely explored.

I arrived at the exact right moment perfection one could say. The economic

group had been established and spent its first meeting, on Wednesday afternoon,

listening to the dream of having a new economic system. Two days later, on

16

Friday, Lisa had resigned, and the following Monday I arrived with the simple

and very small intention (!) of a short visit to learn more about the community.

Had I arrived a month before, Angelina and I would not have been having the

same conversations. On the day I arrived, Soraya and Flor, two young leaders at

the University, whom I had recently met and whom had inspired me to visit,

brought me to meet Angelina. It was only here that I realised they were

embarking on a project I have dreamt of for many years; building a new

economic system with a complementary currency and bank. Speaking for many

hours, (even missing dinner!), the initial encounter between Angelina and

myself, was incredibly vibrant. Many new ideas flowed between us.

The next day, Soraya and Flor brought me to meet Diego who had just assumed

responsibility for looking after the new economics group. Diego had studied

economics at Brazil’s leading school of economics and worked in finance for

several years before moving to Piracanga. Again, our connection sparked a lot of

creativity and we realised that we shared a similar dream. We also saw the

complementary nature of our backgrounds: he possessed the ground knowledge

of Piracanga and Inkiri, while I brought my past experiences in finance and the

theory I had been learning at Schumacher College.

During the first phase of my studies at Schumacher College, I had written an

assignment exploring a complementary currency for Greece and frequently

expressed my dream of designing a new financial system. I found the perfection

of this moment amazing; the different parts coming together, creating something

far beyond the composite parts. I could see in practice that each of us held

something so valuable that, alone, would be insufficient to bring about the dream

that was collectively held.

17

Coming To Piracanga – A Level Deeper…

Angelina and I share the same spiritual teacher, Sri Prem Baba, whom I, like

many of his followers, affectionately call Baba (meaning father in Hindi). She and

I both believe it is he, through the mysterious process of inner guidance, that sent

me here. This connection is part of what enabled us to relate so deeply,

instantaneously, and with so much trust.

Going another layer deeper into my connection with Piracanga, Baba is also the

reason I came to study transition economics at Schumacher College and hence

had something relevant to offer Piracanga in the first place. I attended

Schumacher College in Devon, United Kingdom, for the first time in July 2015. I

had arrived at the College following John Croft, founder of Dragon Dreaming,

with whom I had taken a course one month earlier in Germany. I had been

inspired and wanted to explore Dragon Dreaming further and a course being

held at Schumacher College was my only workable option.

I had never heard of Schumacher College but I fell in love instantly. It was the

first place in the world I felt safe and at home. During the course, Jonathan

Dawson, the head of Economics from the College, mentioned there was still

bursary funding available for students to undertake the Economics for Transition

Masters programme. I shared with him a little of my interests and background,

along with new ideas and paths I was exploring. He was very encouraging and I

decided to consider it for some future point, as I was already committed to

overseeing administration for parts of Baba’s upcoming ‘Brazil season’.

When I arrived in Brazil I discussed the Masters programme with several people,

each of whom said my eyes lit up talking about it. One very dear friend suggested

I speak with Baba directly about it and that I find someone to take over my

position so I could go to study. Despite the encouragement, I was still resisting

the idea as it ‘did not coincide with my plans’.

18

A few days later, on the first official day of Baba’s ‘season’, a Portuguese-English

man I knew distantly called Ragi arrived. ‘Coincidentally’, it was also the first day

of the master’s programme at Schumacher College: 1 September 2015. On this

day, I became very ill, with a strong sense that I was indeed in the wrong place. I

met with Baba to discuss the situation, with Ragi acting as translator. During this

conversation, Baba explained that he saw the economic system as being the basis

of everything on the material plane and that until this changed, nothing else

could. He also spoke about the importance of money and the energy it carries,

and encouraged me to pursue the course.

The following few days were a blur of arrangements enabling me to leave Brazil

and embark on my journey at Schumacher College. Ragi took over my

administrative role. To take a detour in the chronology of this story, unknown to

me at the time, Ragi is the son of Angelina and had helped to create Piracanga.

When, one year later, Angelina told him I was coming, Ragi told her what he

knew of me, having been part of my process the year before. He explained what I

was studying and suggested I could bring some interesting perspectives to them.

As I sit here in Piracanga writing up this story, Ragi has arrived for a short visit.

We acknowledge the incredible perfection of this unfolding, which helped me

enter the community so seamlessly. We observe the full circle involved: Ragi

taking over my administrative position with Baba so I could study, and me

completing my studies by applying teachings from the course he (however

indirectly) helped me enter, in a community he helped to create. We

acknowledge the perfection to this unfolding, so intricate and complex we could

never have orchestrated it ourselves no matter how hard we had tried.

I see the story in 3 dimensional form, layered like an onion with dynamics,

interrelationships and webs connecting across and between levels. I am

reminded, as I have been throughout this process, of the mycelium network

Stephan Harding would so eagerly speak about, living under the soil

redistributing nutrients and information between the whole forest and

19

decomposing plant material. I feel the strength of the connection between the

project and nature, and draw lessons from it for our emerging economic system.

The Finance Years

In order to understand why new economic systems are so important to me, it is

helpful to understand a little of my professional background. I entered into

conventional finance at a young age, idealistic, hard working, and determined to

succeed. Putting all my energy into work, I achieved a level of success that was

rare, even amongst that high achieving culture. In 2 years as a trader, I made

over $100m for the Bank I worked for; an amount almost unimaginable at the

time. In my second year trading, in a difficult economic climate, I was not only

one of the few to generate any profit, I actually generated more than any of my

colleagues, most of whom were older and more experienced.

As the years went by, I came to understand that this work required me to go

against my most deeply held values. I eventually reached a point where money

meant nothing to me. I felt defeated by what I experienced, by what I had seen

people doing and what I had lived through. Lies, manipulation, drugs,

prostitutes… each a part of the shadow side of the industry that was so well

compensated through power and money. As much as possible, I avoided the

politics and the power games that were such a dominant feature of the industry,

preferring to let my figures speak for themselves. As much as anything, I feel now

that this avoidance reflected my fear of ‘the game’ and perhaps of the shadow

itself.

With my soul feeling like it had been destroyed, and longing for another way of

living, I eventually accepted I had to leave. Leave behind deferred shares…

money… reputation…. I was asked by the European Head of Credit to return and

my reply encapsulated the essence of what I had come to understand: “Money is

not everything in life. You cannot buy me back with money.” There were

enticements and there were threats, some of which were ultimately enacted. I

20

was 26, and I walked away, vowing never again to put my energy into something

unless I truly believed in it.

Coming to Piracanga, five and a half years later, I was forced to reconnect with

this past. I had travelled extensively, inwardly and outwardly, and for the first

time I felt ready to open myself again to finance albeit in a completely new way.

My relationship to the Shadow surfaced as a key feature of both the inner and

outer work, here at Piracanga as it has in the previous years. As I dig deeper, I

learn that every person, organisation, community and place has its shadow,

always present no matter how idealistic the dream. I am learning to give this

shadow space rather than trying to fight it, as it is within this space that the

shadow can show itself and dissolve.

21

Spiral To This Moment

In the years following my departure from finance, (and aided by my previous

earnings), I devoted myself fulltime to personal exploration. I followed my inner

voice, which led me from one event to the next, gaining valuable and sometimes

painful lessons that prepared me for further steps. As I look back, I realise life is a

path comprising of unfolding experiences, not a destination. In hindsight, the

perfection of this path feels incredible to me given how so many things ‘went

wrong’ along the way: plans pulled from under my feet; having to change every

flight I booked in five years…. I have learned control is an illusion of the mind

and have been graced by an appreciation of the beauty of emergence. What

looked like chaos has yielded unimaginably wonderful, magical, fruit.

22

Take your well-disciplined strengths and stretch them between two opposing poles

Because inside human beings is where God learns.

(Rainer Maria Rilke, Just as the Winged Energy of Delight, 1924)

ENGAGING WITH THE LITERATURE

I envisage the experience of bringing this project to life as a large melting pot

within myself, where the subjects that most interested me during the Masters

programme at Schumacher College have been ingested, chewed upon and

absorbed. The project has allowed me to follow two of my greatest interests: new

economic theory (focused on money creation, complementary currencies and

new emerging economic practices) and, by working ‘live’ within a community,

the role of a ‘social ‘practitioner’.

My understanding of the numerous subjects that connect to this study have been

shaped and transformed by a large number of writers and practitioners. One of

23

my biggest teachings during this period has involved the assimilation and

combining of different literature and ideas with my outer engagement with the

world. Allowing these to simmer in me over the past months has shifted my

understanding and awareness of the way I engage with the world and prepared

me for the work with the Inkiri community.

Economics And Complementary Currencies

I have immersed myself with economic literature about money creation from

David Graeber, Tom Greco, Silvio Gesell, Charles Eisenstein, NEF, Positive Money

and others. A key insight I gained about money is that it is only energy on this

realm of existence and unlike, nature and life, it does not have cycles like humans

who are born and die, like all of existence. Money is created and self perpetuates,

yet, it has the power to buy anything on this plane. Michael Ende wrote in his

play ‘The Death Dance of Hamelin’ (The Pied Piper of Hamelin) about a

money-worshipping cult, treating it as God-like. He elaborated on money in his

famous book ‘Momo’. Both books, written in the 1970’s have become almost true

representations of our current society.

My keen interest took me deep into the subject of complementary currencies.

From academics such as Bernard Lietaer (2013), I explored the importance of

having multiple currencies. The ecological perspective fascinated me and is, I

believe, an essential dimension of future healthy economic systems. Lietaer

concurs that “it has now been proven that complementary currencies facilitate

transactions that otherwise wouldn’t occur, linking otherwise unused resources

to unmet needs, and encouraging diversity and interconnections that otherwise

wouldn’t exist” (2015).

Case studies on complementary currencies gave me a deeper understanding of

the subject and provided the basis for the work currently taking place in the

Inkiri Economics group. Particularly influential case studies included that of

24

Wögle, Austria and Chiemgauer, Germany , both of which included demurrage. 2 3

The WIR was a good example of a successful measure to iron out economic 4

shocks to the system in Switzerland, with over 75 years of positive results. JAK 5

Bank and its use of interest free loans in Sweden (in Swedish Krona) is

influential, as was Brazil’s Banco Palmas use of interest free loans (in its own 6

currency ‘Palmas’), on which the next phase of the community bank is modelled.

Together, this information has shaped my understanding of money and

complementary currencies, and helped provide a foundation for the Inkiri

currency. Lietaer (2012) draws his teachings from nature, which resonates with

the pillars of the Inkiri community and the work that is emerging from this

2 Wörgl, currency issued in the midst of the Great Depression in Wörgl by the town mayor Michael Unterguggenberger with which the small town was able to fend off the effects of the global crisis (NEF 2015). 3 Chiemgauer, launched in 2003 by a professor and 6 Waldorf students, 2013 recorded 160,000 paper Chiemgauer and 360,000 e-Chiemgauer in circulation driving over €7 million equivalent of turnover (NEF). 635 small and medium size businesses are part of the network, which meet around 50% of local peoples needs, with over 2500 users and 295 clubs (Jean-Vasile 2015). 4 The WIR in Switzerland is an interesting case to examine. It is an independent currency used between commercial entities in Switzerland. Starting in the depression in 1934, it has grown to include 60,000 members and has an annual turnover of around 1-2% of Switzerland’s GDP, or €1.5bn (CCIA 2013). 5 “Furthermore, we now also have empirical proof from 75 years of data from the WIR system in Switzerland that business-to-business complementary currencies tend to be countercyclical with the business cycle of conventional money: they actually help Central Banks in their task of stabilizing the national economy in terms of employment and in smoothing the swings in the business cycle” (Lietaer 2013). 6 Banco Palmas, a community bank established 1998 and since 2000 has been issuing interest free loans in its complementary currency called Palmas. It has now spread to over 100 locations across Brazil (NEF). “Today, the Palmas social currency is understood as a kind of complementary currency, circulating freely together with the national currency (R$ – Real) within the neighborhood. It is still viewed as an integral part of the of the local economic restructuring efforts driven by Banco Palmas that, together with productive microcredit, stimulate the consumption of locally produced goods and services. This proposal strengthens the market, stimulating demand. Through the community members’ strengthened purchasing power and with demand limited to local consumption, the flow of local production and distribution is promoted in the entire neighborhood” (Filho 2012).

25

project, a new economic ecosystem based in nature. The study and

understanding of the academic literature has given me the foundation for the

currency creation but most importantly the basis for the talks and lectures,

which emerged as part of the new economy movement in Piracanga.

Eco-Villages And The Transition Movement

In the field of eco-villages, I was particularly influenced by Jonathan Dawson’s

(2004) work on the setting up of community currencies in the Findhorn

community in Scotland and in Damanhur in Northern Italy. Both communities

successfully implemented community currencies and ‘banks’ in their

communities with countless economic and social benefits. These models,

especially Damanhur’s, were an inspiration for Piracanga , for who the next step 7

after implementation of the community currency is a community bank, Casa

Inkiri. What struck me however is that this literature is rather old (over 10

years). Since this time, there has been somewhat of a refocus from eco-villages to

transition town movements, with eco-villages experiencing a ‘dying out’

phenomenon due to aging populations. With many young people living in towns,

where transition towns are more prevalent, much of the recent research

conducted has focussed in this area. Amongst this literature, I was particularly

interested by Luigi Russi’s (2015) work on the Totnes pound, which highlighted

some important technical issues about implementing complementary currencies.

Working As A ‘Social Practitioner’

Of all the interesting thinkers in this area, I have been particularly inspired by

Patricia Shaw, Ralph Stacey, John Shotter and Allan Kaplan. Their ways of seeing

and engaging with the world have opened me to completely new perspectives

and ways of experiencing life. I have been hugely influenced by the work of

Patricia Shaw and her way of working within organisations. It has been a deep

7 The Inkiri community and Piracanga have a close relationship with Damanhur, who inspired the transition from an eco-village to a community.

26

honour to be able to not only read her work but also have experienced her work

in action, having her as my thesis supervisor and mentor on this path. She has a

talent for working with conversations, drawing from them deeper meaning and

allowing for presence to open up.

Along similar lines, Ralph Stacey’s work with complexity and cycles of deepening

sense making and reflexivity has taught me a lot about how to enter deeper

places of understanding. He provides a very strong theoretical and intellectual

mode of thought of how we might understand complexity and emergence, within

which the practice of working with conversation such as Patricia Shaw’s work is

embedded.

Ralph Stacey shows clearly how he draws on Norbert Elias’ work in order to

understand the importance of responsive processes of relating. He explores how

entire ways of life and ways of governing, and how entire nations have come into

being, through the endless iterations of complex responsive processes of

relating. By relating he means the endless mutual reciprocal process of

responding to each other through communicative activity. While one could term

this conversation, Elias talk more precisely about responsive relating,

continuously creating the emergence of I and We identities.

On similar lines, Allan Kaplan also works with conversations but he comes at it

through Goethe and phenomenological approach, whereas Shaw comes from a

complexity approach grounded in the theoretical perspective of Ralph Stacey.

Shaw, Kaplan and Elias’ engagement through conversation have shaped the way I

conducted my work as a ‘social practitioner’ in the field, I drew very much on

Shaw’s work as she guided me through the process, and enjoyed connecting to

Kaplan’s phenomenological approach to the unfolding of events.

Shaw draws on John Shotter in her work. Shotter’s work fascinates me,

particularly his ideas on engagement with life. Reading his works opened a door

for me into a different kind of awareness and way of seeing the world. Further,

27

Elias influenced me in how to cultivate what he calls the paradox of involved

detachment, in which you are deeply involved and yet attempt to maintain that

enlarged mentality where you hold conflicting perspectives in your imagination.

Attempting to see a broader dynamic and not getting trapped in a single view.

28

We are simultaneously actors as well as spectators on the great stage of life.

(Bohr, quoted in Honner, 1987, p.1)

METHODOLOGY

Conceptual Approach

I deliberately took a nonlinear approach to this Masters project and to the thesis

itself. Rather than developing fixed questions to answer or setting a hypothesis

to test, I set a clear intention to make space for a natural and synchronistic

unfolding of events; an approach that ultimately resulted in me arriving in

Piracanga. I do not wish to now pretend some other, more conventional

approach, masking the dissertation using a traditional subject-object academic

manner.

The thesis process has been an unfolding from within, taking shape as I

endeavoured to be fully alive through continuous engagement with the world. It

is very much research with and not upon a community, and I explicitly

acknowledge that I, along with the participants, have actively shaped and been

shaped by the process. Intentionality, synchronicity, trust and deep reflection

have been fundamental elements of the project, as has been the deliberate

closing to certain options in order to make space for others to emerge.

The approach has some parallels with the more widely known collaborative

inquiry approach from the field of action research. Although I feel I have gone far

beyond its boundaries, the collaborative inquiry approach did provide some

useful concepts and frameworks to draw upon in certain moments (e.g. the

process of working in cycles presented by Peter Reason, 2001). In truth though,

my approach was far too heavily based in emergence to fit so tidily into a

fourfold research cycle of planning, action, observation and reflection.

29

Many times, I chose to drop this structure and follow emerging threads. In this

respect, my approach was closer to Ralph Stacey’s (2002) use of iterative cycles

of deepening sense making and using reflexivity. 8

Some traditional researchers might feel what I have done is more accurately

described as the absence of an approach; at worst, a chaotic, disorganised

lurching from one random point to another, sewn together at the last minute in a

desperate attempt to impose some sense of order or deliberateness. To these

people I would suggest you have missed the point. As I see it, the way forward for

our species and our planet requires that we learn to engage with complexity. In

fact, I believe our very survival depends on it. This means we need to learn how

to sit calmly in the discomfort of not knowing, to dance with uncertainty, and to

surrender plans. This is as true in research as it is for any other aspect of life.

Ultimately, for me, this project has been a grand and challenging experiment in

doing exactly this.

Shaw (2006) emphasises this process in that, “It is not a question of whether we

improvise or do not improvise; the question is how much we try to control our

improvising or how much we are wiling to run the risk of not being on top of

what we are doing. Do we dare to trust that meaning will emerge as we are

spontaneously and skilfully working our way forward?”

Practical Applications

Throughout the dissertation period I explored and abandoned many ideas:

working with the feminine; doing a pilgrimage from my father’s homeland

Germany to my mother’s roots in China to teach workshops there for women in

8 “Reflexivity requires us to situate ourselves in the world as a co-creator of the situations in which we find ourselves: to question our assumptions and our role; what we may be saying and not saying; what we may be privileging and taking for granted” (Allen 2016).

30

finance; attending Pat McCabes’ gathering of women’s stories for the land and/or

Martin Shaw’s school of myth… Each was explored and subsequently dropped as

another more compelling door opened. I rented a house near Schumacher

College in order to stay in one place, something that initially felt important, yet

spent the majority of my time away from it when life proved otherwise. Flying to

Greece to dive deeper into presence and spontaneity on a more personal level;

returning to Brazil for ‘two weeks’ to spend time with Prem Baba, only to meet

Flor and Soraya who inspired me to come to Piracanga…

This approach has been deeply challenging. In some respects, it would have been

‘easier’ to take a more conventional approach, making more rigid plans and

holding to them. Saying ‘No’ to openings, new information and other possibilities.

But my time in finance has taught me well the price to be paid for ignoring one’s

inner voice and so, instead, I have had to make peace with continuously stepping

out of my comfort zone. I have had to learn detachment and to practice trust. To

let go of any idea that I know what happens next, or should happen next, and to

attune more closely to synchronicity, the voice of the Universe.

Interestingly my relationship to money became a focal point for me personally

during this time. At the same time as I was diving into the subject with Inkiri and

designing workshops on the subject, I was forced to examine my personal

relationship to scarcity. If I had made solely financially-based decisions, I would

not have ended up at Piracanga in the first place. I had invested in Martin Shaw’s

School of Myth, was paying rent in the UK and remaining in Brazil to visit

Piracanga meant paying extra money to change flights. Having made the decision

to go to Piracanga on other grounds, however, perhaps highlighting the way

Universal ‘flow’ can work, Angelina offered me the opportunity to be her guest

with a room in her house so I am not paying for food in the community kitchen.

Ultimately everything balanced out.

31

Thesis Unfolding Process

This has been a project of engagement: with ideas, with people, with myself and

with life itself. The main tools for this engagement have been conversations,

sometimes informal, and sometimes more formal (e.g. interviews, group

meetings and active discussions). Working with conversations, drawing on

Patricia Shaw’s (2002) method of actively engaging with situation and feeling

what wants to emerge. Working spontaneously. One of the important learnings

for me relates to the engagement between people: it is neither the events nor the

person but the relationship between them that is where life takes place. It is

through the interrelationship and being that emergence happens; where what

one could term ‘magic’ is created.

I held a number of workshops with people from Inkiri and the eco-village, which

enabled a more embodied way of engaging with participants. This brought

deeper levels of healing and self-knowledge regarding their relationships with

money. Open lectures and discussions with different schools within Inkiri, such

as the Nature School and University, also proved a great medium for transmitting

information.

The unfolding of the thesis topic is paralleled in smaller iterations, such as the

writing process. I started putting this piece together, knowing the task would

prove to be challenging. My first draft took the form of an orthodox research

paper; I made an account of the literature, methodology and results, in a very dry

fashion. It mirrored the conditioning of my thinking, academic education and

view of life. My second attempt moved deeper into the process that had played

out, taking a more linear, chronological approach. In the current version,

everything was turned on its head as I attempted to take the reader to a deeper

level, delving into the topics that emerged as most relevant from the second

draft. Deepening the reflections and connecting the story to the metaphor of the

land and ecology.

32

Don’t be satisfied with stories, how things have gone with others.

Unfold your own myth.

(Rumi)

THE ECONOMIC STORY

Throughout my time at Schumacher College and having taken part in Martin

Shaw’s School of Myth, I have come to realise the importance of story and how it

is framed and shared. The words we use and how we bring something to life on

the plane we live on are key to our relations. Our means of communication, how

we have received information from the past, how we currently communicate

with each other and what we will pass onto generations to come.

When I arrived, I asked several people to tell me the story of Piracanga. What is

the dream? What are the pillars of the community and its values? What is the

33

economic history of this place and why the current desire for change? I have

come to believe there is something very special, magical, about Piracanga and its

people who, like magnets, are drawn here from across Brazil, South America and

the world. I felt I would understand this and numerous other things better if I

could just tease out the story I assumed was waiting there to be shared with me.

Angelina gave me her account of the ‘Piracanga dream’ and what this place

means to her. She gave me a detailed account of having arrived on a fishing boat

years earlier, swimming to the shore and realising this was the land she had

dreamed of so long ago. Yet as I asked more questions of more people, it became

apparent that there was not yet an agreed, explicit story. No one could give me a

clear or consistent account of what has actually taken place.

Eventually I came to understand there was no single, coherent story of

Piracanga. As people shared their perspectives with me, it became obvious that

while some of the core details were consistent, people’s accounts and

experiences of them varied enormously. Focusing solely on the ‘agreed facts’

would clearly produce a very lifeless facsimile of the events surrounding the

community, meaning another approach was needed. In the end, what I thought

would be an easy task of finding out ‘the story’ actually became a creative

process in itself; the birthing of a rich story of this land, the community and its

people, where all dimensions of life are interwoven and connected.

My Personal Process Of Writing The Account

The process of helping ‘to give birth’ to the story of Piracanga and Inkiri

presented a considerable challenge for me. I had not anticipated this yet, as I

reflect now, the fact this was so hardly seems surprising. Perhaps naively, I had

thought identifying the economic story of Piracanga would be a simple and

uncontroversial task, collecting ‘some facts’ and putting it together in a cohesive

manner. What I experienced was quite different.

34

The story, or more accurately the stories I was being presented with by various

people, and the place I am writing it from are more important than I had

imagined. As the work I am doing is very subjective and I am part of the

unfolding, it is inevitably my perspective that is being presented here. The more

time I spend in Piracanga and the deeper I dig, the more evident it becomes to

me what the work of a ‘social practitioner’ actually is. I find myself deeply

questioning my ability to wisely discern what information I should present and

what I might withhold from the reader. It’s not simply deciding how to deal with

sensitive information; among other things, there’s information that feels

insignificant but may not necessarily be so. There are ramifications to my choices

and I cannot fully anticipate what those might be.

I have also struggled deeply with the tension that perhaps inevitably arises from

being ‘sponsored’ into the community by its leader. One member of the

community told me I am the only person he has known over the years who has

come to Piracanga as an ‘outsider’ and been allowed to participate so fully, and

exert so much influence. Add to this, I am (happily!) living as Angelina’s guest,

sleeping in Ragi’s room in the house and eating food she has paid for. The same

person told me I have been given more privileges than some permanent

members of the community.

Being embraced in this way has been a wonderful experience for me. Doors have

been opened, enabling me to begin to fulfil a personal dream of mine: to work

with others to explore new economic systems and tools. Being embraced with

open arms by Angelina and the Inkiri community generally has been wonderful

and I am grateful. I am very aware of the privileged position I am in.

At the same time, part of me feels indebted and potentially constrained by this

favoured position. I am conscious both that the experiences I am having are

shaped by this dynamic and that that the dynamic is shaping the way I am

behaving. One part of me feels open to inquire into all the avenues, using

Piracanga and the community as a fertile ground to explore what I have learnt;

35

yet the other part of me feels almost guilty to witness and bring to light that

which is not yet aligned with the dream. As had been the case in my banking

career, I was coming in contact with the Shadow and I was unsure how to

respond.

The inner tension I felt escalated over time, culminating in physical symptoms

including two days of dizziness, a churning stomach and pain throughout my

body. Even though I recognised that some of what I was observing were simply

natural tensions arising from differing perspectives, I was unsure how to write

about them. Confiding in Ragi, I realised that these tensions exists side by side

with the light. They are part of life. Denying the shadow is denying a part of the

whole; the dilemma of my position and how to represent the work reiterates the

role of the participant-observer. As an embodied witness, I experienced the

tension in movement within the community in my own body.

I also shared my dilemma with Patricia Shaw, my thesis supervisor, who

responded with the following:

Dear Mar Reading your mail I felt almost glad! The work is deepening and touching the

genuine complexity of our social/community/organisational lives as human beings – particularly the shadow as you say of what actually happens despite our dreams and good intentions. It is easy to work with dreams and the pristine unspoiltness of the future. This is why so many facilitators/consultants/leaders are so keen to keep this focus. Asking the questions about where are we now and how we come to here always opens up the multiple and often conflictual paths of experience that different people have lived through. Circumstances and situations may be held in common but the experience of them may be very different and all politics comes from the attempt to impose one version of the story and suppress others so that they fall into the shadow i.e. They are not in the light of the public domain but gather around the edges. It is important to understand this light/dark not so much as good/bad but as publicly acknowledged/suppressed.

It is not possible to institute a new economical way of living without addressing

political/ethical issues. The web of relating is a web of power-relating (Elias says that there are always imbalances of power in relations in terms of the continuous dynamics of inclusion/exclusion by which I and We identities are formed and evolve. (The often “horrific” events that bedevil so many

36

communities usually have dynamics of inclusion/exclusion at their source.) Hannah Arendt would say that the very essence of ethical political action is that it cultivates an enlarged mentality – a willingness to visit and inhabit the perspective of many players in any situation – only then do we see something “in the round”.

So to prepare the ground for a new economics is inevitably to turn over the soil, to

dig up old roots and bones. In the metaphor of working the land, this breaking up and aerating the soil is what allows nutrients to be re-absorbed and increases fertility for the new seeds.

I think it is essential to include this in your dissertation. Including your own

recognition of feeling mired in the favoured position you have under the protection of someone “in power” in the community. How do you use ethically the access this has allowed you on behalf the whole community and not become silenced by the apparent ties of patronage? How do you use your reflexivity (your ability to see the world in what is happening”) to encourage a fuller picture to emerge? One that allows people to live with and out of the past and not live in the past. These are true acts of leadership, whether your role is one of researcher, leader, consultant, facilitator – no matter.

You clearly are in the right place at the right time! This is difficult work – be modest

and gentle with yourself but seek a larger common truth/story that many can recognise themselves and their world in and which may allow them to go on from here in new ways…

Be care- full

Patricia Patricia guided me to see beyond ‘good and bad’ to that of what politics truly is,

the public acknowledgement and suppression of stories. This resonated, as I felt

my presence brought space in the community for stories that had been pushed to

the periphery to emerge. I had innocently embarked on a new economic system,

without taking into account the political structure of the place, which came to the

forefront during my time working the soil. Patricia showed me that the

credibility of my work, and people’s trust in me, stems from my ability to see and

bring to attention that I was indeed in a favourable position. Through naming it, I

could work deeply within the space I have taken within the Inkiri community.

37

A Brief Account Of The Economic Story

What follows is an attempt to condense years of life at Piracanga, experienced by

many, many people, and present it in a way that is meaningful, recognisable to

those involved and understandable to newcomers. Needless to say, this task has

been challenging. I am calling it the ‘economic story’ as economics is the focus of

the project, yet more truthfully, it is the story (or perhaps ‘a’ story) of Piracanga

generally, spiralling around with economics as its focal point. I have focused on

the seven years that have past since the community, newly named Inkiri, was

formally created from within the eco-village named Piracanga. This was the point

at which active attention was given to creating a deliberate economic life within

the community.

The act of committing this story to paper lends it an air of definitiveness and

permanence, yet in truth it has neither. This story is alive and constantly

evolving. It is non linear. After much thinking and several attempts at writing, I

have chosen to organise ideas by timing and by theme, both of which suggest a

linearity and discreteness to events that in truth does not exist. Woven

throughout are specific stories experienced and told to me during my time at

Piracanga, which serve both to illustrate and to shed light. I have endeavoured to

use these accounts as a starting point to reach deeper layers of meaning. Again I

am acutely aware of the impact I have on the shaping of the story.

The Four Waves

I have mentally organised Piracanga’s economic story into four phases, which I’m

calling ‘waves’. The first three have past while the fourth is what we are entering

into currently. I chose the term ‘waves’ because I feel it captures an essential

essence: they are movements of energy, flowing into each other, containing far

more than economics.

38

In my view the evolution mirrors, on a small scale, the transition that parts of the

world have passed through. Wave 1 can be viewed as a form of a

socialist/communist system, wave 2, the beginnings of a capitalist system, where

some autonomy has been incorporated, and wave 3 takes the community further

into a decentralisation process where full autonomy is given to projects. I see

this movement as a microcosm for the global economic changes that have taken

place and therefore an important ground for exploration of a new economic

system, where we create ways of living in harmony within nature instead of

separated from it. This transition is represented by the fourth wave Inkiri is

moving into. 9

For the most part, I have presented the story here in terms of key themes that

emerged through engagement with members of Inkiri. I did not actively seek out

these topics. Rather they emerged as key issues to be addressed during this

period of working the land, levelling the soil in preparation for planting and in

the process, uncovering old bones and allowing things to come to the surface.

Wave 1

This phase of Piracanga’s story is called ‘the magical period’. It opened seven

years ago, when the community was first created, when 20-30 people arrived in

Piracanga from Uruguay and Argentina over a ten-week period. The community

had no paid jobs for them so the people worked as volunteers, receiving

accommodation, food, transport and internet access in exchange for their efforts.

This system lasted for some time but was widely considered unbalanced as some

community members, in contrast, were earning over R$30,000 per month for

their efforts. Under the system at the time, however, there was no extra money to

pay them.

9 In a discussion with Angelina (as the aura reading school works around the energetic system of chakras) we talked about the idea of the economic systems having passed through the first three chakras, the root, sacral and solar plexus (as the 3 economic systems) and now moving into the fourth economic system, the heart chakra.

39

Out of the growing sense of inequality came a sense that radical change was

needed. Gabriel, Angelina’s husband at the time, proposed an experiment where

everyone would pay their money into a ‘fund’ and receive the same salary of

R$600 per month, covering everyone’s basic needs. Name ‘Fundo Magico’ (magic

fund), the idea was to use the money remaining after the base income was

distributed to fund new projects that would benefit the community. This system,

taking them to the other extreme of the spectrum, was in place for approximately

1.5 years.

How this experiment was perceived varied between people. There seems to be

consensus that a huge flourishing of creativity took place during this time, with

many new projects being created. In fact, most of the projects that currently exist

were born during this period including the cultural centre, university, nature

school and natural products. The courses in CUDS were full, the shop made a

good profit and the community started becoming very abundant. R$600 per

month was a lot of money for many people at that time, subsequently raised to

R$1000 per month after the implementation of a ‘Piracanga 1000’ campaign, and

largely people described feeling taken care of.

There was a sense of collaboration and camaraderie about this period that can be

connected back to this approach. In conversation, I was told how willing people

were to help each other and how everyone was working for the benefit of the

community as a whole, meaning no obvious division between yours and mine,

this project or that.

At the same time, there was a lack of clarity about what people did. Roles were

not defined and there was no connection between your activities and where the

money came from. I was told of a story of a man who would spend all day

walking around speaking to people, making connections and relaying

information. His role felt key in the networking of information and people yet no

one really knew exactly what he was doing.

40

This dramatic shift also presented challenges for some. One community member

explained to me that she had spent five hours shedding tears about the new

system, part of a very strong personal process around the shift. She was a

teacher, giving therapies and also owned properties in Piracanga which she

rented out for extra income. This system meant that 100% of the money she

earned inside Piracanga and 50% of any courses she gave outside would be paid

into the fund and, in return, she would receive R$600 per month. This was an

extreme shift in income for her and her family but she agreed to it as she trusted

the community decision at the time.

It had other consequences too. Another community member discussed how she

had always been very motivated and would constantly come up with creative

ideas to make money. The current café, ‘Acai do Mar’, started as a small table

where she sold baked goods made with her friends. She would create crafts and

sell them at the Saturday market. Under this new system, however, any extra

money she made had to go to the fund and she would receive the standard R$600

at the end of the month. Over time, she felt stifled and demotivated by the

system. In discussions, she termed this period ‘spiritual communism’, having

visited Cuba and witnessed a similar impact of the system on people there.

In time, it became apparent that changes were needed to the system. In addition

to the issues discussed above, two additional issues emerged. The first is that

there was an energetic imbalance in the system. Some people were working a lot

compared with others and receiving the same amount of money. Energetically,

they were receiving a lot less proportionate to their contribution. Secondly, there

were a few people who were noticeably disoriented within the system, trapped

in a lack of productivity. As they received a salary per month regardless of their

contribution, they lost motivation and started ‘free riding’.

I find the variation in people’s responses to the system fascinating. What I draw

from it is not a ‘failure’ of the system per se but rather its inability to adapt to

41

people’s needs. Kaplan (2005) suggests that we “…respect human freedom not in

theory but as the very essence of a social practice. We understand change as

erratic, dependent on context and underlying energy, involving complex social

transformation in tune with cultural realities, and we work to free situations and

release peoples’ energies to respond to intricate challenges and demands, rather

than creating systems for managing change”.

Wave 2

Lasting around nine months, wave 2 involved a shift towards a more capitalist

approach to the economy. Instead of receiving a fixed monthly salary, people

were required to find a job within a community project and, through that project,

generate an income for the community. Everyone still received the same amount

of salary (at this point R$1,200) per month, but now they were required to work

8 hours of work per day. Within each project, a bonus of 10% of the profit

generated was shared equally between all members each month. This was the

first time that income was organised within projects and that community

members were expected to assume responsibility for paying salaries. Previously,

they were paid centrally. Projects were given a three-month period to make the

transition to becoming autonomous, with the community fund aiding in this

transition.

During this period, projects became professionalised and, due to the 10% bonus

scheme, people felt incentivised to work hard on their projects. The transition

required that people assume a level of financial responsibility they may not have

previously experienced, which some found challenging. One of the project

leaders described this as a very difficult time for her as she possessed few skills

for managing project finances. Angelina recalls that this was one of the main

reasons she wanted the community to make this transition, to open a space for

people to see where they were in relation to money and to learn how to work

with it. She also recalled how Gabriel, her former partner, had been amazed at

how so many people had arrived at Piracanga with no means of making a living.

42

Inevitably some tensions emerged along the way. Some projects were more

profitable than others, meaning people received different amounts of money

depending on which project they were part of. A new system was implemented

where, every three-months, 10% of the total profits from the projects were

distributed across all who worked in them. Ultimately this was only

implemented for a short period of time.

Now that people had to make payments themselves, there was also a felt sense of

loss. From the inception of the community, everyone paid a monthly contribution

to the school of R$50, (now increased to R$70), and a further donation of 10%

salary to the community fund. Previously this money had been removed

automatically through the centralised financial management system, with people

receiving a net payment. Under the new system, people received a gross salary

and had to make the contributions themselves. One community member

explained how she felt she was receiving a lot less this way.

During this period, the sense of collaboration so present previously started to

break down as people became motivated to make more profit for their own

projects. Energy went into growing existing projects, meaning fewer new

projects were born, and community investments were also cut back.

The structure behind the system was very complicated and, at the project level,

there was still a lot of centralised control in this system. Such that the wages

were centrally agreed, and financial payments and accounts were taken care by

Lisa.

Wave 3

Wave 3 represents the system currently in place within the community and that

which it is in a deliberate process of evolving beyond. Set up over a year ago, it is

characterised by greater decentralisation and a more extreme form of capitalism.

43

Each project team has total autonomy over its decisions including what to pay

people and the amount donated to the community fund. Project teams have also

taken responsibility for project management; for the first time, dealing with all

project finances.

This has been a maturing process and there have been mixed results. Some

project teams lost track of their finances, keeping no records of project

transactions. Deliberate efforts to increase transparency within and across

projects led to financial information being shared across project leaders,

meaning shared knowledge of project and personal incomes, expenses and

community donations. This brought about some comparison and judgements,

and there was clear competition between project teams. Poaching occurred

where teams offered a desired person higher wages and there was generally a

strong sense of separation. It was suggested to me people had become blinded to

the interdependence that exists between projects and within the community,

believing they could create abundance alone. Instead of helping each other freely,

projects expected to be paid for their time and efforts, the focus shifted to

monetary benefits. These were the conditions into which I arrived and which

were helping to drive a desire for a new way forward.

Fourth Wave – A Beginning…

To better understand what is needed for the economic shift sought, the

economics team (including myself) developed a questionnaire for community 10

members. We consulted many sources including the Gross National Happiness

survey [GNH] in an attempt to obtain a full picture of people’s current positions

and their hopes for the future. All 45 members of the community completed the

questionnaire. The result we found most interesting was that people were very

happy in their jobs, working not for the money but to feel fulfilled. There was a

10 I have included the questionnaire in Appendix to give the reader a sense of the issues we explored. I did not include the detailed results as I felt it was beyond the scope of the current discussion.

44

strong consensus that the system was imbalanced and an openness to change. No

one opposed the idea of a local currency.

We are not subjects actively projecting meaning into things, but instead we become receptive subjects for the meaning which appears.

(Henri Bortoft)

CROSS-CUTTING THEMES

This chapter explores key issues that cut across the waves. This section was

perhaps the most difficult to write as it required me to connect people’s

experiences and accounts to particular themes, like exclusion or power and

control. As is always the case, there is no separation and everything connects.