.ow Back Pain - Functional Movement

Transcript of .ow Back Pain - Functional Movement

.ow Back Painin Ath ie teS Peter Georgilopoulos

Peter Georgilopoulos is an APA Sports Physiotherapist currently working out of his private practice on the Gold Coast. He has

had numerous involvement with sporting organisations but most notable appointments were with the Australian Olympic Team

In Sydney and the Socceroos from 1990 - 2000. In this article, Peter discusses the common problem of low back pain and how

coaches may be able to help their athletes.

Throughout our lives, 85% of us will experience one significantepisode of low back pain. Statistically whilst 90% of thesecases will recover within a three month period, at least 50% ofthese initial cases will suffer one or more further recurrence oflow back pain at some stage beyond the initial episode.

Low back pain (LBP) is the most common disability aftectingthose under the age of 45 which may indicate that disc relatedproblems may account for a significant number of these cases.Beyond 45 years of age, discs tend to lose their plasticity aspart of a generalised degenerative (arfhritic) condition whereasdisc related pathology tends to occur in active, younger peoplewho overload their backs through work or sporf.

The sporting population, in particular, is at high risk of injuryeither through one specific overload or traumatic episodesuch as landing poorly from a jump or as a result of recurrentloading of discs and joints such as experienced by running.

Running in spikes, which öfters no shock absorbing qualities,running on hard surfaces, poor flexibility of supportingmusculature and other soft tissue structures can result inoverloading vulnerable spinal structures thereby exposingathletes to significant risk of injury.

The most common factor in predisposing athletes to gradualonset low back pain is poor weight bearing biomechanics. Flatfeet (pes planus) is one of the most common factors in whyweight bearing joints in the spine, as well as hips and kneescan incur excessive loading leading to joint inflammation, lackof flexibility and ultimately gradual onset of pain.

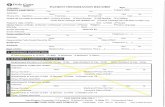

Musculoskeletal screening is therefore imperative inhelping to identify biomechanical anomalies that can lead toasymmetrical weight bearing in athletes and increased riskof low back pain. Leg length discrepancies, knocked kneeposture (genu valgum), bow legged posture (genu varus), hipjoint stiffness or pathology and scoliosis are also risk factorsin developing back pain (amongst other possible overuseconditions).

Common Sites of Low Back P

Athletes will experience the same type of spinal injuries andconditions as the general non-sporting population but havean increased risk of developing parficular spinal conditions

which may be related to repetitive loading associated withsome sports or exercises that may be commonly performedin training.

Endurance athletes can present with stress fractures of thespine, in parficular female athletes who may develop pseudo- menopausal alterations in their hormone levels linked totheir training which in turn can lead to a reduction in bonedensity. A reduction in bone density with prolonged andintense loading can easily progress to pathology.

Athletes underfaking repetitive spinal rotation with overloadsuch as javelin throwers can incur stress fractures andultimately fractures of the pars interarficularis, a bridge ofbone connecting the body of the verfebrae to the facet joints.This condition is well documented in cricket fast bowlers andis frequently seen in soccer players who repeatedly practicekicking "curved" corner kicks for the same reasons. Hurdlerscan incur disc trauma as a result of repeating the actionof landing from a height with the pelvis tilted and rotated.Improper form on the squat rack, performing dead lifts orheavy leg press when fatigued can also result in disc traumawhich may require considerable recovery time.

Being aware of possible risk factors in each discipline canlead to early intervention at the first sign of back pain, andmore imporfantly, highlight the imporfance to athletes of theneed to underfake a thorough recovery protocol following eachtraining session. A recovery programme should include multi-directional stretches to the lumbar spine, stretches to thepsoas and piriformis muscles, internal and external rotationof both hips as well as gently stretching the anterior hip jointstructures to regain hip joint extension.

Self traction (i.e. hanging loosely from a high bar helps to"decompress" impacted weight bearing structures such asdiscs, facet joints and hip joints.

Implications of Impact Loading the Lumbar Spine:As discussed previously, the lumbar spine is well placedanatomically to absorb extraordinary levels of repeatedimpact. The discs öfter significant force dispersement whilstthe normal lumbar lordosis (curvature) enables force to betransmifted throughout the spine evenly.

15

As we have also discussed earlier, deviation away from a"balance" spine can rapidly lead to specific overloading atone level or structure which can lead to disc, ligamentcus orbony trauma.

What is not often considered is the eftect of repeatedoverloading on neural (nerve) structures in the lumbar spine.

Athletes (and Coaches) are frequently faced with insidiousonset of progressive lumbar stiftness over several trainingsessions. Athletes may not necessarily report spine pain butmay report progressive "tightness" with associated buftock,groin and/or hamstring tightness.

Numerous researches have postulated the relationshipbetween the lumbar spine and hamstring injury. In two recentrandomised controlled studies by the author in associationwith Bond University, seventy two subjects were evenlydivided into three groups. Hamstring flexibility was recordedin all subjects prior to intervention. In the control group, nointervention was undertaken whilst the remaining subjectsunderwent sustained hamstring stretching for a period ofthree or six minutes or manual spinal joint mobilisation by theresearches for either a three or six minute duration.

Interestingly, the three minute stretching group did not showsignificant (>5%) improvement when reassessed whilst the6 minute stretching group displayed just beyond significant(>5%) improvement. By comparison both the three minuteand six minute spinal mobilisation groups displayed wellbeyond significant levels of improvement outperforming thestretching groups in both studies.

These results bring into question the importance of the iumbarspine and sciatic nerve in hamstring flexibility. Optimally,achieving hamstring flexibility may be best served by initiallystretching or mobilising the lumbar spine before undertakingstretches of the hamstring muscles.

Athletes should aim to achieve a measurable degree ofhamstring flexibility as part of their recovery strategy. It isreasonable to expect that track and field athletes achieveat least 90 degrees of straight leg raise lying in supinebefore attempting a training session. Failing to achieve ameasureable degree of hamstring flexibility can contributeto both hamstring injury as well as being a major factor inrecurrent back pain and resultant diminished performance.

Anterior hip joint starting position Anterior hip joint with overpressure

16

TFL stretch

ISelf traction

Piriformis stretch Psoas stretch

17

step 1 siump

Internai rotation of the hip External rotation of the hip

Copyright of Modern Athlete & Coach is the property of Australian Track & Field Coaches Association and its

content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's

express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.