Outsourcing and the Personnel Paradox

-

Upload

kathleen-rose-sabalburo -

Category

Documents

-

view

218 -

download

0

Transcript of Outsourcing and the Personnel Paradox

8/3/2019 Outsourcing and the Personnel Paradox

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/outsourcing-and-the-personnel-paradox 1/10

Outsourcing and the Personnel ParadoxW illiam M, Fitzpatrick, Villanova University

Samuel A . DiLullo, Villanova University

IntroductionOutsourcing is designed to enhance organiza-tional competitiveness by subcontracting keyvalue-chain activities to other firms (Harrigan,1984; Razzaq ue and Sheng, 1998; Fitzpatrickand B urke, 2000). It has been estimated that at

current rates, 50% of U.S. manufacturing activi-ties may be outsourced to firms in 28 emergingor developing countries by 2015. Additionally,outsourcing of services by U.S. firms is expectedto lead to the migration of four million jobs tothese nations by 2008 (Merrifield, 2006).

The literature on virtual organizations hasassigned a descriptive term, " hub s," to firms thatextensively utilize outsourcers or independentcontractors to accomplish strategic objectives(Dickerson, 1998). Named for their resemblanceto the structure of a wagon wheel, organizationalhubs are the irreducible core or center of an or-ganization that unifies and links the efforts ofsubcontractors and outsourcers. Typically,organizational hubs comprise administrativeinfrastructures that facilitate m anagement ofactivities deemed essential to both the firm'score competencies and the coordination of itsoutsourcer activities (Gaibraith, 1995; Dick-erson, 1998; Goldman, 1998; Fitzpatrick andBurke, 2000). When outsourcing, hubs generallysubcontract business activities that are notcritical to their core comp etencies or can beperformed more effectively by other firms

(Webster, 1992; Christie,and Levary, 1998;Fitzpatrick and Burke, 2001; Rippin and Sayles,1999). Thus, outsourcing permits hubs to en-hance their performance by utilizing the corecompetencies of other firms (Buono, 1997).These can include 1) access to intellectual prop-erties, 2) unique manufacturing or service effi-ciencies, 3) lower costs due to governmentsubsidies, 4) specialized workforce talents orexpertise, and 5) lower labor rates (Cinelli andHuffman, 2006; Elliot, 2006; Kakamanu and

Portanova, 2006; Menifieid, 2006). These lasttwo core competencies often justify the off-shoring variant of outsourcing activities (Kass,2004; Kakamanu and Portanova, 2006).

In the United S tates, governmen tal authoritiesare concerned that firms are outsourcing to avoid

payroll taxes, workmen's compensation, over-time compensation, and legal liabilities associ-ated with the violation of labor or immigrationlaws (Osterman, 2005; Pearce, 2006). In a vari-ety of recent judicial rulings, the courts havesought to redefine compensatory and liabilityissues for firms or hubs when using subcontrac-tors (In Re FedEx Ground Packaging System,Inc., 2005; Braun Consulting Group, 2006;Baker v. Flint Engineering & ConstructionCO.^ 1998; The Coastal Corporation v. Torres,et ai, 2004). The redefinition of these legal andfinancial responsibilities has evolved from acareful exam ination of the degree of control thatfirms have over the business activities of theirindependent contractors. The purpose of thisarticle is to explore this emerging con trol doc-trine and examine how the application of thisdoctrine may erode some of the traditional legalprotections and labor cost advantages experi-enced by firms when using independent contrac-tors.

The Control Doctrine and theCom pensatory Status of Independent

Subcontractors

• Control and the legal determ inauts of em-ployee and independent contractor status

In the United S tates, the utility of outsourcingmethodologies for purposes of reducing laborcosts and financial or legal liabilities frequentlydepends on whether legal or tax authorities af-ford outsourcer personnel the status of either (a)hub employees or (b) independent contractors{In re FedEx Ground Package System, Inc.,

SAM ADVANCED MANAGEMENT JOURNAL

8/3/2019 Outsourcing and the Personnel Paradox

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/outsourcing-and-the-personnel-paradox 2/10

2005). The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) hasdeveloped legal criteria for establishing person-nel employment status (IRS, 2007). As evidentfrom the IRS g uidelines (see Table 1), personnelemployment status is largely contingent on thedegree of financial, behavioral, and relationalcontrol over them by hub organizations. From afinancial perspective, independent contractorsand outsourcers are generally responsible for (1)making their own asset investments to completetask assignments, and (2) are paid by the joband not reimbursed for job-related expenses.Conversely, employee status is conferred to em -ployees when they are paid wages or salaries,reimbursed for job-related expenses, and rely onhub organizations to provide tools, equipment,or other assets needed to perform their tasks.Employees are supervised and directed by man-agers of the hub organization. Behaviorally,

independent contractors exhibit higher levels ofindependence and autonomy with respect to theplanning, timing, sequencing, and work method-ologies associated with task activities. For inde-pendent contractors, job tenure expires at thecompletion of the project or task assignment. Ingeneral, employees have more continuous andlonger-term employment relationships with buborganizations.

These IRS guidelines for classifying person-nel have significant ramifications for the overallcost effectiveness and success of outsourcing

business models when used by hubs. As demon-

strated in recent litigation, affording "emp loyeestatus" to a hub's independent contractors cansignificantly increase labor costs (i.e.. overtimecompensation, social security contributions.Medicare contributions, unemployment taxes,etc.), administrative responsibilities, and down-stream civil liabilities for these hub organiza-tions (Osterman, 2005 ; In Re FedEx, 2005;Zavala v. Wal-Mart Stores, Inc., 2005; TheCoastal Corporation v. Torres, et al., 2004;Lavallie v. Pride International, Inc., 2004).

Con trol and the Revised CompensatoryStatus of Independent C ontractors

• Overtime com pensation, expense reim-bursements, employee benefits and payrolltaxes

In 2004, FedEx employed approximately 17,000

independent contractors as package deliverydrivers, who serviced either multiple routes orsingle work areas. In a case bought before theCalifornia Superior Court, single-route employ-ees sought to be classified as employees andthereby become eligible for a variety of em-ployee benefits and expense reimbursements.These plaintiffs argued that both the nature oftheir work and the control mechanisms deployedby FedEx to supervise them constituted an "em-ployment" rather than an "independent contrac-tor" relationship (Estrada et al v. FedEx Ground

Package System, Inc., 2006). By virtue of their

Table 1. IRS Criteria for Employee and Independent Contractor Status

Control Factor

Financial Control

Worker Investment

Expenses

Method of payment

Risk

Behavioral ControlSupervision

Tools and materials

Details of work

Other employment

Evaluation system

Relationship of Parties

Duration

Benefits

Employee

No investment

Reimbursed

Salary or wag es

No opportunity for profit or loss

Employer supervises

Supplied by employer

Controlled by employer

Works only for employer

Measures details

Extended continuous period

Provided benefits

Independent C ontractor

Significant Investment

Not reimbursed

By the job

Opportunity for profit and loss

No supervision

Supplied by worker

Controlled by worker

Works for multiple employers

Measures end result

Specific project

Receives no benefits

Adapted from IRS Guidelines (2007)

SUMMER 2007

8/3/2019 Outsourcing and the Personnel Paradox

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/outsourcing-and-the-personnel-paradox 3/10

operating agreements, single-route drivers were(a) governed by specific employment guidelines,(b) issued FedEx business cards, (c) wore cloth-ing and drove vehicles with FedEx logos, and(d) engaged in exclusive, long-term task activi-ties in support of FedEx business objectives. Inadjudicating the case, the California court heldthat the "EedEx Ground purposely created con-trois of an employment nature, hoping that inspite of those strictures, the status would still beseen and considered to be that of an independentcontractor" (Braun Consulting Group, 2004:7).These behavioral controls over single-route driv-ers were evident in a variety of ways. Thesedrivers received direct supervision and operatingguidelines from FedEx policy manuals or per-sonnel. Equipment (e.g., uniforms, vehicles, andbusiness cards) was provided to the drivers andincorporated FedEx logos. Additionally, the

employment relationship was long term with nospecific termination date or circumstances, anddrivers were contractually compelled to worksolely for FedEx. As can be seen from Table 1,each of these personnel requirements is moreconsistent with the behavioral characteristicsgoverning employees than those associated withindependent contractor/subcontractor relation-ships. This lawsuit (now on appeal) has gener-ated a variety of other class action suits againstEedEx by independent contractors seeking togain "em ployee status" (In Re F edEx, 2005).Should these lawsuits be decided in favor of the

plaintiffs, F edE x's cost efficiencies may erodelegally mandated expense reimbursements, em-ployee benefits, and payroll taxes associatedwith these newly classified "employees"(Osterman, 2005).

The Fair Labor Standards Act (1938) uses asimilar methodology for classifying independentcontractors and em ployees. In a 1998 case in-volving this Act (Baker v. Flint Engineering &Construction C o, 1998), a group of oil rig w eld-ers sought to legally modify their employmentstatus to qualify for overtime com pensation and

other benefits normally provided to employees.These welders had entered into a contract withBaker entitled an Agreement with IndependentContractor. This agreement indicated that theintent of Baker and the welders w as to "establishand maintain an 'independent relationship'rather than an employer-employee relationship"(Baker v. Flint Engineering & Construction Co.,1998:1439). However, in reviewing the natureof the work activity, the court established thatBaker exhibited behavioral and financial control

over these workers consistent with an employ-ment and not an independent contractor relation-ship. In justifying the reclassification of theseindependent contractors as employees, the courtexamined six critical factors, including: 1) thedegree of control exerted by the alleged em-ployer over the worker, 2) the worker's opportu-nity for profit or loss, 3) the worker's investmentin the business, 4) the permanence of the work-ing relationship, 5) the degree to which skill isrequired to perform the work, and 6) the extentto which the work is an integral part of the al-leged employer's b usiness" (Baker v. Flint Engi-neering & Construction Co., 1998: 1440).

In reviewing these criteria, the court notedthat the welders received significant directionand supervision from Flint's foreman. Weldersdepended on Flint's foreman for originatingwork schedules, rest breaks, sequencing tasks

with other construction crafts, and for providingwork orders. The court also concluded thatdespite being highly skilled, welders did notactively participate in work-related decision-making. Therefore, both the supervisory ar-rangement and the lack of decision-makingactivities were deemed to be evidence of Flint'sbehavioral control over the welders and found tobe inconsistent with the autonomy generallyafforded independent contractors. From a finan-cial perspective, independent contractors gener-ally have opportunities for business profit orloss. However, Flint paid its welders an h ourlysalary or wage. This precluded these workersfrom actually generating business profits orlosses. Additionally, while the welders wereresponsible for providing their own weldingequipment, this investment was considered mi-nor relative to the assets Elint had com mitted tothis commercial relationship. Therefore, thecourt concluded that Flint maintained a level offinancial control over the workers commensuratewith an employer-employee relationship. Perma-nence of the welder's working relationship withFlint was also found to parallel the job tenure of

other employees in the oil and gas industry andwas not deemed to be a significant factor in de-termining the workers' employment classifica-tion. Einally, since welding operations werecentral to Flint's core business activities, thewelders were deemed to support task activitiescharacteristic of essential employee functions.Therefore, despite signing independent contrac-tor agreements, welders were granted the statusof employees under the Fair Labor StandardsAct (1938). This made Flint liable for employee

SAM ADVANCED MAN AGEMENT JOURNAL

8/3/2019 Outsourcing and the Personnel Paradox

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/outsourcing-and-the-personnel-paradox 4/10

benefits and overtime compensation commensu-rate with this new employment status, whichresulted in an overall increase in their labor andoperating costs,

• Workmen's compensation and financialcontrol over independent contractors

Court rulings in The C oastal Corporation v.Torres (2004) present an interesting variation onthe issue of financial control, employment status,and liability for workmen's compensation.Coastal Corporation is involved in the refiningof petroleum products. Like many firms in thisindustry. Coastal Corporation sought to organizemany of its strategic business units as indepen-dent subsidiaries. Each subsidiary had its ownmanagement personnel who assumed responsi-bility for specific day-to-day operations of thebusiness unit. However, Coastal Corporation did

exhibit some generalized control and coordinat-ing capabilities over these business units by vir-tue of formulating a centralized budget.

One of these subsidiaries. Coastal Refining &Marketing, Inc., operated a refmery in CorpusChristi, Texas. In M ay of 1999, a pressure vesselat this refinery ruptured and subsequently ex-ploded, severely injuring a number of workers.The investigation found that the cause of therupture and explosion was likely due to internalcorrosion in the pressure ve ssel. The injuredworkers filed suit against Coastal Corporationfor gross negligence. They argued that by virtueof its budgetary authority over subsidiaries.Coastal had assumed responsibility for "controlover maintenance, turnaround and inspectionmatters at the plant. . . [and] by limiting expen-ditures, controlled and influenced its subsidiaryin a way that directly resulted in [the workers']injuries." (Coastal Corporation v. Torres, 2004:777, 779). Thus, under this legal theory of con-trol, the plaintiffs' attorney argued that CoastalCorporation was obligated to pay workmen'scompensation to the injured workers. Whenadjudicated before a district court, a jury held

Coastal Corporation to be liable for these work-ers ' injuries.

However, the appellate court reversed this jurydecision, largely based on an examination of thecontrol doctrine. The court held that generalbudgetary control over a subsidiary's operationdid not constitute direct control over o perationalresponsibilities. Thus, liability for workman'scompensation would only occur if Coastal hadcontrol over the means, methods, and detailsrelated to the implementation of work-related

safety policies. Therefore, the negligence-basedcontrol theory advocated by the injured workersfailed to dem onstrate the level of detailed behav-ioral or financial control needed to establishCoastal's liability.

• Workman's compensation and piercing thecorporate veil

Workman's compensation liability was also thesubject of the Lavallie v. Pride International,Inc. (2004) case. Mr. Lavallie was employed byPride International Personnel, Ltd (Pride Person-nel), an independent subsidiary of Pride Interna-tional, Inc. Pride Personnel recruited workers toprovide a variety of services for its corporateparent (Pride International). While performingservices on a ship owned by Pride Internationaland its subsidiaries, Mr. Lavallie suffered seriousinjuries to his lower back. Despite numerous

requests by Lavallie, neither Pride Internationalnor its subsidiaries agreed to pay his medicalfees or compensate him for his injuries. After sixmonths of unpaid medical leave, his employ-ment with Pride Personnel was terminated. Inhis subsequent lawsuit, Mr. Lavallie contendedthat the parent corporation of Pride Personnel(Pride International) was responsible for com-pensating him for injuries sustained while work-ing for one its subsidiaries. A s a matter of law,injured workers usually have recourse onlyagainst the corporate entity responsible for theliability and not its corporate parent (Baker v.Raymond, 1981). Therefore, in order to seekrecompense from the parent corporation,Lavallie's attorneys needed to establish the civilliability of Pride International by piercing thecorporate veil of ownership.

When organizations seek to establish each oftheir operating subsidiaries as independent cor-porations, they are attempting to insulate them-selves from the civil liabilities generated by theirprincipal business units. To establish civil liabili-ties of the parent for the activities of its off-spring, plaintiffs must pierce the corporate veil

of ownership by demonstrating that corporateparents exhibit significant control over the ac-tivities of their subsidiaries. In Baker v. Ray-mond (\9S\), the court established the ability oflitigants to establish civil liabilities for parentcorporations when their subsidiaries served asbusiness conduits or "alter ego s." This level ofdirection or control over subsidiaries erodes theindependence of these business units and makesthe parent corporation responsible for their ac-tions. In determining whether the corporate veil

SUMMER 2007

8/3/2019 Outsourcing and the Personnel Paradox

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/outsourcing-and-the-personnel-paradox 5/10

of liability has been breached, courts have exam-ined nine factors, including: "1) common stockown ership [i.e., does the parent own all of thestock in the subsidiary], 2) common directorsor officers, 3) whether the parent finances thesubsidiary, 4) whether the parent caused theincorporation of the subsidiary, 5) whether the

subsidiary operates with grossly inadequatecapital, 6) whether the parent pays the salariesand other expenses or losses of the subsidiary, 7)whether the subsidiary receives any businessexcept that given to it by the parent, 8) whetherthe parent uses the subsidiary's property as itsown , and 9) whether the directors and officers ofthe subsidiary act independently in the interestof that company or take orders from the parentand act in the parent's interest" (Lavallie v. PrideInternational, 2004: 3 ). In the Lavallie case, thehigh level of overlap in corporate officers be-

tween Pride International and Pride Personneland the undercapitalization of Pride Personnelwere considered by the court to indicate thesubsidiary's true lack of independence. SincePride Personnel was acting as a business conduitfor Pride International, it was held that the par-ent could be sued for civil liabihties generatedby its offspring.

Apparent C ontrol and the Civil LiabilitiesAssociated with Outsourcer ActivitiesAs a principle of law, employers are gen erally

not held to be legally accountable for civil li-abilities arising from the activities of their inde-pendent contractors. This liability shield stemsfrom the fact that employers have no direct con-trol over the activities of independent contractorsand their personnel (C larkson, Miller, Jentz andCross, 2004 ). However, in a variety of recentcourt cases involving medical practitioners, ap-plication of the "apparent agency doctrine" hascircumvented this liability shield (Alstott, 2004).The apparent agency doctrine is based in part onthe notion that appearances can be deceiving.Und er this doctrine, firms or hubs can be held

liable for the actions of their independen t con -tractors if these c ontractors are perceived byclients to be employees under the "apparentcontrol" of the hub. In Baptist Memorial Hospi-tal System v. Sampson (1998), the Texas Su-preme Court set forth criteria by which hospitalswould be liable for the actions of their indepen-dent contractors. This liability would be estab-lished to the degree that patients " ( 1 ) . . . had areasonable belief that the physician was theagent or employee of the hospital; (2) such be-

lief was genera ted by the hosp ital affirmativelyholding out the physician as its agent or em-ployee or knowingly permitting the physician tohold herself out [as such], and (3) [patients]. . . justifiably relied on . . . [this] .. . representa-tion of authority" (Baptist Mem orial HospitalSystem v. Sampson, 1998:949). Belief that a

physician is an employee and not an independentcontractor can occur when hospitals fail toovertly disclose this outsourcing relationship. InSword V. NKC Hospitals, Inc. (1999), the courtruled that this failure of disclosure could occureven when admission forms clearly stipulatedthat physicians working in the hospital wereindependent contractors. In this case, a matemitypatient was admitted to NKC hospital for deliv-ery of her child and subseq uently suffered fromanesthesia difficulties due to alleged physicianmalpractice. Advertisements for the women's

pavilion indicated that the hospital's medicalstaff was composed only of physicians specializ-ing in obstetrics and anesthesiology. In thecourt's opinion, this advertising program gavepotential clients the impression that (a) the hos-pital was the complete medical provider, and (b)the medical staff were NKC employees and un-der the direct control of the hospital. Addition-ally, other than the disclaimer on the admissionforms, the hospital used no other overt tech-niques to disclose their use of independent con-tracting physicians. Since the hospital hadcreated the appearance that these physicians

were employees, NKC was therefore required toassume legal liability for their action s.

Control, Empioyment Law, and Crim inalLitigation Risks

• Independent contractors and the hiring ofillegal workers

In 2001 and 2003, the Immigration and Custom sEnforcement Division (ICE) of the Departmentof Homeland Security conducted a variety ofemployment "raids" on Wal-Mart stores in 21

states. During these raids, 345 illegal aliens werearrested. These "illegals" were employed byindependent contractors providing janitorial andcustodial services to Wal-Mart. During the ensu-ing investigation and criminal complaint, ICEalleged thai Wal-Mart and its independent con-tractors were both complicit in violating theImmigration and Reform Act of 1986 (Pearce,2006). As noted, firms or hubs had traditionallynot been held liable for the actions of their inde-pendent contractors (Clarkson, Miller, Jentz and

SAM ADVANCED MANAGEMENT JOURNAL

8/3/2019 Outsourcing and the Personnel Paradox

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/outsourcing-and-the-personnel-paradox 6/10

Cross, 2004). However, ICE contended that Wal-Mart's complicity was evidenced by its permit-ting independent contractors to knowinglyassign "illegal wo rkers" to perform tasks in Wal-Mart stores. On May 18, 2005, the Departmentof Justice and ICE announced an out-of-courtsettlement of this issue. In exchange for drop -

ping the criminal complaint, Wal-Mart signed aconsent decree and paid an $11 million fine(Pearce, 2006). The terms of this consent decreeestablished new oversight responsibilities forWal-Mart when dealing with independent con-tractors. Wal-Mart was required to develop aprogram that would (a) monitor and verify thecompliance of independent contractors withimmigration laws, and (b) provide store manage-ment with training regarding their responsibili-ties in preventing unauthorized aliens fromworking in Wal-Mart facilities (P earce, 2006).

While the consent decree did not require Wal-Mart to admit guilt, it did establish a series ofnew legal responsibilities and fmancial liabilitiesfor Wal-Mart when dealing with the employmentpractices of independent contractors.

• Control and the redefinition of criminal andcivil liabilities when dealing with ou tsourcers

The Wal-Mart consent decree has potentiallybroad implications for others electing to useindependent contractors. Should the consentdecree evolve into an industry-wide precedent,

hubs may be forced to develop employmentoversight programs and assume added financialresponsibilities for the inadvertent or intentionalviolation of employment law by such contrac-tors. These oversight programs might also serveto reinforce the hub's behavioral control overindependent contractor activities. As noted in theprior discussion of IRS guidelines and selectedcourt cases, behavioral control has (1) often beenused as a legal justification for affording inde-pendent contractors the status of employees, and(2) created hub liabilities for a variety of unan-ticipated labor costs, taxes, civil and criminal

liabilities. Therefore, if applied to the activitiesof other hubs and independent contractors, theWal-Mart decree has significant implications forredefining the competitive value and cost sav-ings traditionally associated with the outsourcingbusiness model.

Control and O ffshoring V ariants ofOutsourcing StrategiesAs noted, hubs have often outsourced businessactivities to subcontractors in other countries to

exploit situational advantages in costs and spe-cialized workforce expertise (Kass, 2004;Kakamanu and Portanova, 2006). However,achieving these economic benefits is stronglycontingent on domestic labor and corporate lawsin the outsourcer's country of origin, and bilat-eral treaties or economic agreements that jointly

influence the strategic autonomy and responsi-bilities of U.S. hubs and their foreignoutsourcers (Offshore Outsourcing.org, 2007).An exam ple of a bilateral treaty with im plica-tions for behavioral and financial control andcost effectiveness of offshoring strategies is theU.S.-India Tax Treaty (Shah. 2006; Tax Conven-tion with the Republic of India, 1991). Article 9seeks to evaluate the independence of theoutsourcing relationship between hub organiza-tions and Indian outsourcers based upon a doc-trine of control. Therefore, if hubs exhibit

significant levels of managerial control overoutsourcer activities, the global profits they earnas a result of outsourcer work become taxable inIndia (Tax Convention with the Republic of In-dia, 1991). Article 5 of this treaty also indirectlyaddresses elements of the control doctrine indefining hub-outsourcer relationships and subse-quent tax liabilities. It states that the loss of au-tonomy by Indian outsourcers or businesssubsidiaries when dealing with hubs may resultin the reclassification of the Indian firms as per-manent establishments (RE.) of the hub. Underthe treaty, this is likely to occur if business ac-

tivities between the hub and Indian outsourcer orsubsidiary are not characterized by "arms-length" transactions (Shah, 2006). Erosion ofthese arms-length activities can occur when (1)hubs fail to establish more contract-orientedcompensation methodologies for outsourcers, (2)hubs use their own employees for prolongeddirect supervision of outsourcer business activi-ties, or (3) the Indian outsourcer or subsidiary ispermitted to negotiate contracts for the hub orconduct hub-related business outside of India.The first two of these criteria resemble elements

of the IRS fmancial and behavioral control doc-trines used to evaluate or determine independentcontractor status (IRS, 2007). The second andthird criteria also suggest that the outsourcer orsubsidiary is merely a business conduit for hubcompetitive activities. Should any of these threeconditions a rise, (a) PE . status can be affordedto the Indian outsourcer or subsidiary, and (b)global profits that the h ub earns on the IndianP.E.'s work are subject to Indian taxation. Th esetax liabilities may subsequently erode many of

SUMMER 2007

8/3/2019 Outsourcing and the Personnel Paradox

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/outsourcing-and-the-personnel-paradox 7/10

the cost savings traditionally associated w ithoffshoring strategies. These outcom es under theU.S.-India Tax Treaty are directly analogous tothe control issues and erosion of labor cost ben-efits experienced by hubs when outsourcing toU.S. firms.

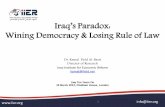

Managerial Implications and S uggestionsTo preserve the viability of the outsourcing orindependent contractor business model, firms

and hubs may have to revise the typical contract-ing methodologies used for coordinating theactivities of their subcontractor personnel. Asnoted in Figure 1, firms and hubs using indepen-dent contractors or outsourcers must be sure toimplement behavioral and financial controlmethodologies consistent with IRS guidelines,

court rulings, and international treaties to escapeadditional taxes, labor costs, civil and criminalliabilities. These control methodologies are

Figure 1. Control and the Management of Outsourcers and Independent Contractors

B E H AVI O RAL

C O N T R O L

APPARENT^

C O N T R O L "

FINANCIAL^

C O N T R O L "

1. Parent organizations should insure adequate

capitalization of their independent subsidiaries in orderfor them to achieve fmancial autonom y.

2. Parent organizations should create general financial

budgets only and avoid micromanagement of

expenditures by independent subsidiaries.

3 . Payments to independent contractors (ICs) should not

resemble wages/salaries. ICs should have the

opportunity to experience profits or losses and pay for

their own exp enses from contract fees.

1. Hubs should not maintain a direct

supervisory relationship with IC personnel.

2. Hubs should assign goals and provide

general project scheduling information toIC management .

3 . IC management should assume

responsibility for communicating work

goals, schedules, and quality control

objectives to their own personnel.

1. ICs should wear identification or uniforms

that specifically identify them as outsourcerand not hub personnel.

2. At hub service locations, signs and oth er

materials should notify clients that

ICs/subcontractors are being used.

3 . IC persormel should verbally inform clients

of their subcontractor affiliation.

10 SAM ADVANCED MANAGEMENT JOURNAL

8/3/2019 Outsourcing and the Personnel Paradox

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/outsourcing-and-the-personnel-paradox 8/10

designed to establish a level of true indepe n-dence between the activities of independent con-tractors, subsidiaries, and hubs. From a financialcontrol perspective, hubs must ensure that thefinancial linkages binding them to theiroutsourcers or contractors and subsidiaries per-mit these latter parties to exhibit sustainable

levels of indepen dence. For h ubs, the financialindependence of subsidiaries can be achieved byestablishing adequate capitalization and budget-ary autonomy among these latter firms. There-fore, parent firms and hubs must provide both anadequate resource base for their corporate off-spring and permit them to allocate and supervisetheir own expenditures without undue influenceor micromanagement (Coastal Corporation v.Torres, 2004). Relationships with independentcontractors should also exemplify elements offinancial independence. Consistent with IRS

(2007) guidelines. Figure1

proposes that thisfinancial independence be established by struc-turing payments to independent contractors sothat (a) compensation does not resemble tradi-tional wages or salaries, and (b) outsourcershave the opportunity to experience profits orlosses and assume responsibility for their ownexpenses (Baker v. Flint Engineering & Con-struction Co., 1998).

With respect to behavioral control, hubsshould give independent contractors significantautonomy with respect to the completion of as-signments and responsibilities. Creating thisautonomous relationship can be facilitated byensuring that hub s do not exercise significantoversight of the employ ees and activities of theirindependent contractors (IRS, 2007). Therefore,independent contractors should remain respon-sible for project managem ent activities, workscheduling, and quality assurance. When usingthe personnel of independent contractors to pro-vide services, hubs should act affirmatively toavoid the appearance of control and shouldclarify this employment status for clients andpatrons. To deal with this apparent control issue,

outsourcer personnel should wear identificationor uniforms signifying their independent con-tractor status and should inform clients of theirstatus. Hubs should also inform clients and cus-tomers of their use of independent contractorsthrough signs or other materials.

Conclusion

Outsourcing has been heralded as a strategypermitting firms and hubs to simultaneouslyincrease their competitive flexibility and reduce

a variety of costs and legal liabilities (Kakamanuand Ponanova, 2006; Merrifield, 2006; Cinelliand Huffman, 200 6). However, in the U nitedStates, the competitive benefits of this strategyare being targeted through legal doctrines ofcontrol (In Re FedEx Ground Package System.Inc., 2005; Baker v. Flint Engineering & C on-

struction Com pany, 1998). Consisting of behav-ioral, fmancial, and apparent dimensions, thisdoctrine of control has eroded the traditionalindependence of outsourcers by reclassifyingtheir personnel as employees of hub organiza-tions. When upheld by the courts, this reclassifi-cation has resulted in the imposition of newcompensatory obligations on those usingoutsourcers, independent contractors, or inde-pendent business subsidiaries. Many of thesefirms have now been required to assume fman-cial and legal responsibilities for overtime com-

pensation, workm an's compensation, payrolltaxes, and civil litigation costs or judgmentsgenerated by their outsourcer cadre (Osterman,2005). This, in turn, has raised the level of costsnot generally anticipated with business modelsbased on outsourcing (Osterman, 2005; LavallieV. Pride International, Inc., 2004). To bettermana ge these new fmancial and legal liabilities,this paper recommends that firms and hubsshould take affirmative steps to (1) understandthe legal complexities of the control doctrine asrepresented in emerging case law, and (2) intro-duce a variety of contractor management strate-

gies designed to preserve true independencebetween themselves and their outsourcer cadre.As noted by the courts, freedom from costs andliabilities may only accrue to firms that maxi-mize the autonomy of their outsourcers.

Dr. Fitzpatrick's teaching and publishing activi-ties are in the areas of strategic planning anddecision-making, competitive intelligence sys-tems, corporate security management, intellec-tual property m anagement, and organizationaldesign and general management. SamuelDiLullo, an attorney, teaches business law andconducts research on bankruptcy, contracts, andconstitutional and intellectual property law.

REFERENCESAlstott, A. (2004). Hospital liability for negligence of inde-

pendent contractor physicians under principles of appar-

ent agency. Journal of Legal Medicine. 25.485-504.

Baker v. Flint Engineering &Construction Company. (1998).

LU F. 3d 1436.

Baker v. Raymond.International, Inc. (I98t). 656 F. 2d 173.

SUMMER 2007 11

8/3/2019 Outsourcing and the Personnel Paradox

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/outsourcing-and-the-personnel-paradox 9/10

Baptist Memorial Hospital System v. Sampson. (1998). 969

S.W. 2d 94 5-950 .

Birch V. Illinois Bone & Joint Institute. Ltd. (2006). U.S. Dist.

Lexis 7022.

Buono, A. F. (1997). Enhancing strategic partnerships. Jour-

nal of Organizational Change Management^ /0 ,251 -266.

Braun Consulting G roup. (2004, Winter). FedEx Ground v s.

Ups; Two worldviews. Braun Consulting News, 1 (6) 1-6. Retr ieved Nov emb er 17, 200 6, f rom h ttp: / /

www.braunconsulting.com/bcg/newslaners/winter2004/

winter2004Lhtmi

Christie, P. M. J., and Levary, R. R. (1998 , July/Au gust). Vir-

tual corporations: Recipe for success. Industrial Manage-

ment. 40{4).l-[ I.

Cinelli, G. M., and Huffman, J. K. (2006). Outsourcing: Is it

really worlh the cost? Intellectual Property and Technol-

ogy Law Journal, 18(4), 21-23.

Clarkson, K., Miller, R., Jentz, G., Cross, F. (2004). West's

business law (9'' ed.l. Mason, OH : Thompson/South-West-

em .

Dickerson; C. M. (1998, January). V irtual organizations: From

dominance to opportunism. New Zealand Journal of In-dustrial Relations. 35-46.

Elliot, G. (2006). International outsourcing; Values vs. eco-

nomics. Quality Progress. i9(8) , 20-25.

Ernst and Young. (2006, June). Ruling on foreign companies

with captive business process outsourcing units. Interna-

tional Tax Review, 1.

Estrada et al. v. FEDEX Ground Packaging System. Inc.

(2006). Court of Appeal of California Lexis 10580.

Fair Labor Standards Act. (1938). 29 U.S.C.A. 203.

Fitzpatrick, W.M., and Burke, D.R. (2000). Form, functions

and financial performance realities for the virtual organi-

zation. SAM Advanced Management Journal. 65(3), 13 -

20 .Fitzpatrick, W.M., and D.R. Burke (2001, Auttjmn). Virtual

venturing and entry b arriers: Redefining the strategic land-

scape. SAM Advanced Management Journal, 66(4) , 22 -

30 .

Gaibraith, J.R. (1995). Designing organizations. San Fran-

cisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Goldman, S.L. (199 8. May/June). From bricks to bytes: Cre-

ating the virtual healthcare organization. The H ealthcare

Forum Journal. 4 5 ^ 7 .

In re FedEx Ground Package System. Inc. (2005). 381F. Supp

2dl380.

Internal Revenue Service. (2007). Employee or independent

contractor? Retrieved January 20, 2007, from http://

www.irsgov/govt/fslg/artic!e/0..id=l 10344,00.html

Kakanamu, P.. and Portanova, A. (2(X)6). Outsourcing: Its

benefits, drawbacks and other related issues. Journal of

the American Academy of Business, 9(2), 1-7.

Kass, E. (2004, February 2). On again, ofF again. Network

World, 34- 36 .Lao, N., and WU, T. C. (2006). Outsourcing operations: A

case of one machine tool manufacturer and its subcon-

tractor in Taiwan. The Business Review, 5(2), 155-162.

Lavallie v. Pride International. Inc. (2004) . 2004 WL

1950321.

Merrifield, D. B. (2006). Make outsourcing a core compe-

tency. Research Technology Management. 49(3), 10-13.

Pearce, J. (2006). The dangerous intersection of independent

contractor law and the immigration reform and control

act: The impact of the Wai-Mart settlement. Lewis and

Clark Law Review, 10, 597- 623 .

Offshore Outsourcing.org. (2007). Legal issues: Offshore

outsourcing. Retr ieved May 28. 2007. f rom http: / /

www .of fshoreoutsourcing.org/legal- issues-of fshore-outsourcing.asp

Osterman, R. (2005). A new division of labor: Independent

Contractor or employee. Sacramento Bee. Sunday Metro

Final Edition. Dl.

Razzaque, M. A., and Sheng, C. C. (1998). Outsourcing of

logistics fiinctions: A literature survey. InternationaUour-

nat of Physical Distribution and Logistics Mana gement,

25(2), 89-107 .

Shah . P. P. (2(X)6). Direct tax es: A dvance rulings. Retrieved

Nov ember 14, 2006 , from http://aiftpoinline .org/joum al/

mayO6/Direct_Taxes_Advance_Ruling.htm

Sword V. NKC Hospitals. Inc. (1999). 714 N.E. 2d. 142.

Rippin, K.M.,and Sayles, L.R. (1999). Insider strategies foroutsourcing information systems. New York: Oxford Uni-

versity Press.

Tax Conven tion with the Republic of India. (1991). Retrieved

May 28,20 07, from http://undefed.com/ForTaxProfs/Trea-

ties/lndia.pdf

The Coastal Corporation v. Torres, Bourland and Natividad

(2004). 133S . W. 3d776 .

Web ster. Jr., F.E. (1992 , October). The chan ging role of mar-

keting in the corporation. Journal of Marketing, 5 6 , 1 - 1 7 .

Zavala v. Wal-Mart Stores. Inc. (2005). 393 F. Supp 2d295.

"GLOBAL CHALLENGES AND GOVERNANCE"

SAM 2007 BUSINESS CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS AVAILABLE SOON IN CD FORMAT

To order please call: 361-825-6045 or e-mail: moustafa.abdeisamadfgitamiicc.edu

Special price $25.00 (postage for overseas $5.00)

12 SAM ADVANCED MANAGEMENT JOURNAL

8/3/2019 Outsourcing and the Personnel Paradox

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/outsourcing-and-the-personnel-paradox 10/10