Otoplasty: something old, something new. Reconstruction of the external ear using fresh cadaver...

-

Upload

geoffrey-campbell -

Category

Documents

-

view

215 -

download

1

Transcript of Otoplasty: something old, something new. Reconstruction of the external ear using fresh cadaver...

British .kxmal of Plastic Surgery (1983) 36, 262-266 @ 1983 The Trustees of British Association of Plastic Surgeons

Otoplasty: something old, something new. Reconstruction of the external ear using fresh cadaver homograft ear cartilage and a sternomastoid myocutaneous flap

GEOFFREY CAMPBELL

Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Wentworth Hospital, University of Natal, Durban, South Africa

Summary- By combining the very old concept of using fresh cadaver homograft ear cartilage with the more modern idea of a musculo-cutaneous flap, a new ear has been constructed for a patient who was considered unsuitable for standard reconstructive procedures.

The early cosmetic result appears satisfactory and the patient’s hearing has been significantly improved.

Notwithstanding the superb results produced in this field by the pioneers of reconstructive surgery and more recently by Tanzer, Brent and others, there remains a group of patients in whom dense scarring over the face and side of the head may preclude ear reconstruction by conventional techniques. If such patients are to receive a new ear it should be constructed in an unscarred distant part of the body and then in good time be transferred to its definitive site.

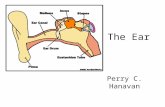

The concept

The arc of rotation of the classically described sternomastoid musculo-cutaneous flap is ideally suited as a vehicle for such a manoeuvre, provided a respectable ear could be constructed or placed at the root of the neck. This “ear” would of course lie in an inverted position so that when the flap was elevated it would assume its upright anatomical position (Fig. 1). The muscle bulk would, hopefully, restore the facial contour after radical excision of the dense scar tissue to create a “bed” for the new ear.

A backward glance Fig. 1

Harold Gillies once commented that failure to Figure l-Diagrammatic representation of the arc of rotation

provide acceptable ears for such patients of a Sterno-mastoid myocutaneous flap used as vehicle to

“ transfer the cartilaginous framework of a fresh cadaver ear that . . . does not lie in plastic surgery per se, but

rather in our inability to exploit it . . .“. He has been previously implanted into the lower part of the neck.

frequently used maternal ear cartilage to witness to his fine results, reminding us that much reconstruct ears for children and also made use of of his work was done in the pre-antibiotic era with fresh human cadaver ear cartilage (homograft) and instruments and sutures now relegated to medical fresh ox cartilage (heterograft). History bears museums.

262

CARTILAGE HOMOGRAFT EAR OTOPLASTY STERNOMASTOID MYOCUTANEOUS FLAP 263

Harold Kirkham read a paper to a meeting in Augusta, Georgia (USA) in 1939 in which he remarked “. . . what better framework than ear cartilage itself, if when transplanted it would remain as cartilage? . . .“. He used human cadaver ear cartilage for ear reconstructions and reported long-term success in some cases. In the same paper he noted that “. . . despite the opinion of some authorities that much transplanted ear cartilage is resorbed or converted to fibrous tissue, I have found this not to be the case . . .”

Monasterio when he visited South Africa in 1981, described his use of homograft cartilaginous nasal septum in rhinoplastic surgery and showed excellent results five years or longer after operation. He also discussed the potential value of homograft auricular cartilage in reconstructive surgery.

Finally a computer search of the literature referring to the use of fresh homograft ear cartilage in ear reconstruction encouraged me to attempt a clinical trial for the following reasons:

(9

(ii)

(iii)

As a complete unit, the architecture is obviously perfect. Provided all the perichondrium is removed antigenicity is low. In South Africa medico-legal provision is made for certain specialised hospitals to obtain fresh cadaver ears.

Case report

A 35year-old man presented a year after a vicious assault by repeated blows to the head with a panga. His left ear had been destroyed and its place taken by dense fibrous tissue. There was no evidence of a conchal fossa or an auditory canal. The post-auricular skin was very badly scarred. The only remaining portion was the apical rim of the helix and even this was distorted by fibrous tissue (Fig. 2). Clinical audiometry revealed absent air conduction but moderately good bone conduction that indicated a functioning inner ear mechanism. Assessment of the middle ear ossicles was not possible. The patient insisted on having some form of external ear reconstruction, expressing the hope that his hearing might also be improved. Though clearly bewildered by the surgical plan as explained he agreed to undergo surgery.

Preparation of donor cartilage

Having been notified of a suitable fresh cadaver (the body was still warm) an impression was taken of the donor’s left ear using silastic foam. This procedure took only five minutes. The ear was then surgically cleaned, removed in toto with a scalpel and taken immediately to

Fig. 2

Figure 2-Close-up view to show the ear destroyed by a panga assault.

Fig. 3

Figure 3-A fresh cadaver ear cartilage. The perichondrium has been removed and the cartilage fenestrated with a “leather punch”.

264 BRITISH JOURNAL OF PLASTIC SURGERY

the operating room where the skin and perichondrium were meticulously removed under the sterile conditions. The entire cartilage was then elaborately fenestrated using a sterile leather-punch which proved ideal for the job (Fig. 3). The cartilage was then washed in normal saline, sprayed with Betadine aerosol, wrapped in a single layer of Bactigras, sealed in Op-site membrane and placed overnight in a deep freeze.

Implantation of donor cartilage

The following day, under gene-al anaesthesia, the entire cartilage was implanted in an inverted position at the base of the patient’s neck above the left Sterno-clavicular joint. The lower end of the sternomastoid muscle was gently split to accommodate the conchal fossa and auditory canal. The cartilage was secured with a few strategically placed 6/O Dexon sutures. The remaining ear cartilage was bedecked by thinly undermined dermis which conformed well to the auricular convolutions (Fig. 4). The previously prepared soft silastic foam

Fig. 4

Figure 4-A fresh cadaver ear cartilage has been implanted at the root of the neck. Note its inverted position and its thin dermal cover.

ear-mould was now placed in position and secured by an Op-Site membrane which proved both reliable and comfortable. This mould maintained adequate contact between the dermis and the underlying fenestrated cartilage, without producing pressure-necrosis of the skin.

Ten days later the mould and skin sutures were removed. The patient received both prednisone and

antibiotics in decreasing dosages during the following three weeks, as this has been found to minimise the incidence of pyrexia and the appearance of tender lymph nodes in the submandibular region following implan- tation of homograft cartilage. A period of eight weeks elapsed while cartilage and dermal cover were allowed to settle.

Elevation of new ear

Nine weeks later, under general anaesthesia, the new ear was mobilised gently from the surrounding skin in the root of the neck and elevated as a musculo-cutaneous flap after dividing both the sternal and clavicular heads of sternomastoid. The neck incision was extended in a zig-zag fashion from the mastoid process to the root of the neck, the sternomastoid muscle was dissected and and then rotated upwards through an arc of 180” carrying the new ear with it. All the dense fibrous scar tissue was then excised from the previous site of the destroyed “missing” ear. This produced a defect sufficiently large to accommodate the new ear with its muscular pedicle. There was no evidence of the original

Fig. 5

Figure 5-The new ear has been elevated into position. Note the zig-zag neck incision and the skin-grafted donor site at the base of the neck.

CARTILAGE HOMOGRAFT EAR OTOPLASTY STERNOMASTOID MYOCUTANEOUS FLAP

auditory canal and the new cartilaginous canal was placed in close proximity to the tympanic membrane which was itself badly scarred. A few 6/O Dexon sutures held the new ear in position and the skin incision was closed with a subcuticular 5/O Dexon suture. A Penrose drain was placed at the root of the neck for 48 hours and a small split-skin graft was required to close the donor site at the root of the neck (Fig. 5).

Subsequent adjustments The bulkiness of the island flap with its new ear gave cause for some concern: so too did the absence of an auditory canal. Three weeks later a contouring operation was undertaken. The helix was thinned out through a peripheral incision and the conchal fossa given better definition. The cartilage for the new auditory canal was exposed, trimmed, widened and lined with a thick Thiersch graft. The new canal was then packed with acriflavine-wool round a polythene tube. Finally an ear lobe was constructed from the skin of the island flap (Figs. 6 and 7).

Audiometric assessment

Three months after surgery air-conduction had improved from zero to 50% of normal. Bone conduction Fig. 6

265

was also marginally improved. The patient was delighted Figure 6-Close-up appearance of the new ear. Its bulk has with this very modest improvement in hearing. been reduced and an auditory canal constructed.

Fig. 7

Figure ‘I-Final result showing the new ear and the upper part of the neck incision

266 BRITISH JOURNAL OF PLASTIC SURGERY

Critical evaluation

A reconstruction of this type takes time and effort. Each step is delicately poised between modest success and total failure. Donor ears may not be readily available and relatives of potential donors sometimes react unfavourably to the surgeon’s request for an ear.

The second stage of the operation involves a neck dissection, leaves a zig-zag scar in the neck and a small skin graft in the root of the neck. In dark-skinned patients the scars could well become hypertrophic. The folding of the sternomastoid muscle results in a bulge in the neck at the angle of the mandible, though this disappears within four months as a result of disuse atrophy. The important question of the permanency or

otherwise of the new ear cartilage will only be settled by the passage of time. However, the work of some colleagues in years gone by gives grounds for cautious optimism. If undertaken at all, this is a procedure which at this stage should be reserved for adult patients with severe scarring of the head for whom the creation of a new ear is of paramount importance.

The Author

Geoffrey Campbell, BSc, MB, CbB, FRCS, Plastic Surgeon, Division of Plastic Surgery, Wentworth Hospital, University of Natal, Durban, Republic of South Africa.

Requests for reprints to: Mr Geoffrey Campbell, FRCS, 12A Trent Place, Westville 3630, Natal, Durban, Republic of South Africa.