Opioids for LBP Meta-Analysis JAMA

-

Upload

paul-coelho-md -

Category

Healthcare

-

view

86 -

download

0

Transcript of Opioids for LBP Meta-Analysis JAMA

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

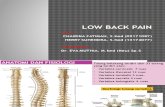

Efficacy, Tolerability, and Dose-Dependent Effectsof Opioid Analgesics for Low Back PainA Systematic Review and Meta-analysisChristina Abdel Shaheed, PhD; Chris G. Maher, PhD; Kylie A. Williams, PhD; Richard Day, MD; Andrew J. McLachlan, PhD

IMPORTANCE Opioid analgesics are commonly used for low back pain, however, to ourknowledge there has been no systematic evaluation of the effect of opioid dose and use ofenrichment study design on estimates of treatment effect.

OBJECTIVE To evaluate efficacy and tolerability of opioids in the management of back pain;and investigate the effect of opioid dose and use of an enrichment study design on treatmenteffect.

DATA SOURCES Medline, EMBASE, CENTRAL, CINAHL, and PsycINFO (inception toSeptember 2015) with citation tracking from eligible randomized clinical trials (RCTs).

STUDY SELECTION Placebo-controlled RCTs in any language.

DATA EXTRACTION AND SYNTHESIS Two authors independently extracted data and assessedrisk of bias. Data were pooled using a random effects model with strength of evidenceassessed using the grading of recommendations assessment, development, and evaluation(GRADE).

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES The primary outcome measure was pain. Pain and disabilityoutcomes were converted to a common 0 to 100 scale, with effects greater than 20 pointsconsidered clinically important.

RESULTS Of 20 included RCTs of opioid analgesics (with a total of 7925 participants), 13 trials(3419 participants) evaluated short-term effects on chronic low back pain, and noplacebo-controlled trials enrolled patients with acute low back pain. In half of these 13 trials,at least 50% of participants withdrew owing to adverse events or lack of efficacy. There wasmoderate-quality evidence that opioid analgesics reduce pain in the short term; meandifference (MD), −10.1 (95% CI, −12.8 to −7.4). Meta-regression revealed a 12.0 point greaterpain relief for every 1 log unit increase in morphine equivalent dose (P = .046). Clinicallyimportant pain relief was not observed within the dose range evaluated (40.0-240.0-mgmorphine equivalents per day). There was no significant effect of enrichment study design.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE For people with chronic low back pain who tolerate themedicine, opioid analgesics provide modest short-term pain relief but the effect is not likelyto be clinically important within guideline recommended doses. Evidence on long-termefficacy is lacking. The efficacy of opioid analgesics in acute low back pain is unknown.

JAMA Intern Med. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.1251Published online May 23, 2016.

Supplemental content atjamainternalmedicine.com

Author Affiliations: Authoraffiliations are listed at the end of thisarticle.

Corresponding Author: Andrew J.McLachlan, PhD, Pharmacy and BankBuilding A15, Faculty of Pharmacy,University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW2006, Australia ([email protected]).

Research

Original Investigation

(Reprinted) E1

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/ by Paul Coelho on 05/23/2016

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

L ow back pain is a common health problem and the lead-ing cause of disability worldwide.1,2 While manage-ment guidelines encourage the prescription of simple an-

algesics for low back pain (eg, paracetamol or nonsteroidalantiinflammatory drugs [NSAIDs]), many people with low backpain are prescribed opioid analgesics.3,4 Findings from theUnited States show that more than half of the people regu-larly treated with prescription opioid analgesics have chroniclow back pain.4 Similarly in Australia the 3 most commonly pre-scribed drugs for back pain are opioid analgesics or opioid an-algesic combinations: oxycodone (11.7%), tramadol (8.2%), andparacetamol and codeine combination (12.1%) (percent of allprescribed medicines for back pain).5,6

Despite the widespread use of opioid analgesics for peoplewith low back pain, there remains uncertainty about 3 centralissues that would guide rational prescribing of these medi-cines for the treatment of people with low back pain. Two re-cent high-quality systematic reviews have shown that, be-cause of a lack of trials, there is uncertainty regarding the efficacyof opioid analgesics for people with acute low back pain7 andalso when these medicines are used long term for chronic lowback pain.8 There is also uncertainty regarding the optimal dos-ing of opioid analgesics because, to our knowledge, there hasbeen no systematic evaluation of how the dose of these medi-cines may influence the size of any treatment effect for peoplewith low back pain.9-14 Finally, there has been little consider-ation of the extent to which an unselected group of opioid-naïve people with low back pain would tolerate or respond toan opioid medicine. For example, many opioid trials use an en-richment study design and exclude participants who do not tol-erate or adequately respond to the opioid analgesic in the run-inphase. Some trials also exclude participants who do not re-spond to or tolerate the opioid analgesic in the randomized phaseof a trial, and therefore the estimate of treatment efficacy is de-rived from only a proportion of participants who were en-rolled in the study to receive opioid analgesics.

The aims of this systematic review were to (1) evaluate theefficacy of opioid analgesics in the management of low backpain, (2) investigate the effect of opioid dose and enrichmentstudy design on treatment effect, and (3) quantify treatmentdiscontinuation (owing to adverse events and lack of effi-cacy) and loss to follow-up in the run-in and randomized phasesof trials.

MethodsData Sources and SearchesMEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Database of Systematic Re-views, CENTRAL, CINAHL, and PsycINFO (inception to endSeptember 2015) were searched for randomized clinical trials(RCTs) evaluating opioid analgesic medicines for nonspecificlow back pain (eTable 1 in the Supplement). In addition wescreened reference lists of included RCTs and relevant sys-tematic reviews to identify additional RCTs (Figure 1). We in-cluded only RCTs enrolling patients with nonspecific low backpain15 (ie, low back pain where a cause [eg, fracture, infec-tion] had not been identified).

After screening titles and abstracts of retrieved studies, 2reviewers drawn from a pool of 3 reviewers (C.A.S., A.J.M., andC.G.M.) independently inspected the full articles of poten-tially eligible RCTs to determine eligibility, with disagree-ments resolved by consensus.

Study SelectionWe included studies in any language evaluating single-ingredient or combination medicines containing an opioid an-algesic for nonspecific acute or chronic low back pain. Studyselection was not restricted by pain duration, comorbid con-dition(s), or concurrent nonopioid or nonanalgesic medica-tion use (eg, to treat hypertension) provided that participantswere stabilized on these medications and the pattern of usewas unchanged throughout the study. We included the ana-tomical therapeutic chemical (ATC)16 codes for drug classes rel-evant to this review in the search.

Figure 1. Summary of Search

17 Articles identified through hand search of reference lists

14 985 Articles identified from databases:

5302520818941865340

MEDLINE

EMBASE

CENTRAL

CINAHL

PsycINFO

376 Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

1908 Duplicates

12 899Studies excluded

Not relevant to topic

13 094 Study titles screened for eligibility

195 Articles identified for abstract review

46 Articles identified forfull review

20 Studies included

Trials excluded

23 Ineligible outcome measure

3 Ineligible study population

149 Trials excluded

24 Other

59 Ineligible outcome measure

12 Ineligible comparison or control

54 Not specific for low back pain

Key PointsQuestion What is the efficacy, tolerability, and dose-dependenteffects of opioid analgesics for low back pain?

Findings In this systematic review we found that recommendeddoses of opioid analgesics (range 40.0-240.0-mg morphineequivalents/day) did not provide clinically meaningful pain relief(> 20 points on a 0-100 point pain scale) in people with chroniclow back pain.

Meaning For people with chronic low back pain who tolerate themedicine, opioid analgesics provide modest short-term pain relief,but the effect is not likely to be clinically important withinguideline-recommended doses.

Research Original Investigation Effects of Opioid Analgesics for Low Back Pain

E2 JAMA Internal Medicine Published online May 23, 2016 (Reprinted) jamainternalmedicine.com

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/ by Paul Coelho on 05/23/2016

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Placebo-controlled RCTs and RCTs comparing 2 drugs fromthe same class or different doses of the same drug were eli-gible for inclusion. Trials were included if they reported pain,disability, or adverse events outcomes. Trials involving pa-tients with a range of pain conditions were included if resultsfor participants with low back pain could be separatelyextracted.

Data Extraction and Quality AssessmentTwo reviewers (C.A.S., C.G.M.) independently extracted out-comes data from published studies. Missing data were ob-tained by contacting authors or estimated using the methodsdescribed in the Cochrane Handbook.17 Analysis of data froma crossover trial was performed according to recommenda-tions in the Cochrane Handbook.17

Risk of bias was assessed using the 11-item PEDro scale(eTable 2 in the Supplement),18-20 a valid and reliable methodof rating methodological quality of individual RCTs.18-20 Eachitem (excluding the item for external validity) was scored aseither present (1) or absent (0) to give a total score out of 10.Rating of trials was carried out by 2 independent raters (C.A.S.plus A.J.M. or C.G.M.) with disagreements resolved by an in-dependent third rater (eTable 3 in the Supplement). Trials scor-ing less than 7 out of 10 on the PEDro scale were consideredto be at high risk of bias; those scoring 7 or more were consid-ered to be at low risk of bias.18

Data Synthesis and AnalysisPain and disability outcomes were converted to a common 0to 100 scale (0, no pain or disability, to 100, worst possible painor disability). The pain intensity measures used in the re-trieved trials were visual analog scale (VAS) scores (scale range,0-100) and numerical rating scale (NRS) scores (range, 0-10).The NRS was converted to the same 0 to100 scale as in the VASbecause these 2 pain measures have been shown to be highlycorrelated and, when transformed, can be used inter-changeably.21 The disability measures used to calculate pooledeffects were Oswestry Disability Index scores (range, 0-100) andRoland–Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ) scores (range,0-24). The RMDQ scores were converted to the same 0 to 100scale as in the Oswestry Disability Index because these 2 ques-tionnaires are highly correlated and share similar psychomet-ric properties.22

We present results as mean differences (MDs) rather thanstandardized mean differences (SMDs) because the bench-marks for clinically important difference in pain and disabil-ity are expressed in points on a 0 to 100 scale, not proportionsof a standard deviation.12,13 We considered a 10-point differ-ence on this 0 to 100 point scale as a ”minimal” difference anda 20-point difference as “clinically important” difference, con-sistent with the proposed thresholds for clinically importantchanges in the chronic pain12 and low back pain literature.13 Toreflect the way that patients typically rate their pain, we con-sidered differences of less than 10 points (out of 100) on thepain or disability scale as unlikely to be noticed by most pa-tients; some patients would notice a difference in the range of10 to 20, points and most people are likely to notice a differ-ence greater than 20 points on the pain or disability scale.

We considered short-term pain relief (follow-up < 3 months)as the primary outcome. Outcomes were grouped into 3 timecategories (with respect to follow-up): short-term (<3 months)intermediate-term (≥3 months, <12 months), and long-term (≥12months). Where multiple time points were available for a singlecategory, the time closest to 6 weeks was chosen for short-term follow-up, 6 months for the intermediate-term, and 12months for the long-term. We conducted a separate analysisto calculate treatment effect sizes for placebo-controlled trialsevaluating combination opioid analgesics containing a simpleanalgesic (eg, paracetamol).

Where there were multiple comparisons from a singlestudy, we divided the number of participants in the commonarm by the number of comparisons, according to recommen-dations in the Cochrane Handbook.17 Meta-analysis was car-ried out using RevMan review management software (ver-sion 5.1) and Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software (version3, Biostat).23 Pooled effects were calculated using a random ef-fects model. Where possible, we explored possible causes ofheterogeneity where I2 values were greater than 40%.

We used the grading of recommendations assessment, de-velopment, and evaluation (GRADE) criteria24 to evaluate theoverall quality of the evidence for an intervention. This methodis described elsewhere,25,26 but briefly the quality of evi-dence was downgraded a level for each of 4 factors: poor studydesign (≥25% of trials, weighted by sample size, had a lowPEDro score [<7 of 10]), inconsistency of results (≥25% of thetrials, weighted by sample size, had results which were not inthe same direction), imprecision (sample size <300), and pub-lication bias (assessed using funnel plot analysis/ Egger re-gression test). Where Egger regression 2-tailed P value was lessthan .10, the overall quality of evidence was downgraded by 1level.27 We did not assess for indirectness (when the trial con-text is not the same as the review question) because this re-view encompassed a specific population. The quality of evi-dence was defined as “high quality,” “moderate quality,” “lowquality,” and “very low quality.”24

As our primary analysis, the pooled effect of single-ingredient opioid analgesics was evaluated at short-term fol-low-up. To evaluate the effect of opioid dose we converted alldoses of opioid analgesics to morphine equivalent doses28 andconducted metaregression to determine the effects of the log-transformed morphine equivalent dose on treatment effect size(for single ingredient opioid analgesic trials). We also con-ducted a simple stratified analysis exploring pooled effects at100 mg or more and less than 100 mg morphine equivalentsper day.

For each trial we collated the number of participants re-ceiving an opioid analgesic who were withdrawn from the trialbecause of adverse events, lack of efficacy, or were lost to fol-low-up, in both the run-in and trial phase of a study. The pro-portion remaining were those who contributed data to the tri-al’s estimate of treatment efficacy. In addition, we explored theeffects of study design (enrichment design [in which patientswho tolerate and respond to the trial medicine in the run-inphase are allowed to continue to the randomization phase ofthe study] vs nonenrichment) on treatment effect usingmetaregression. At the same time we investigated the effect

Effects of Opioid Analgesics for Low Back Pain Original Investigation Research

jamainternalmedicine.com (Reprinted) JAMA Internal Medicine Published online May 23, 2016 E3

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/ by Paul Coelho on 05/23/2016

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

of opioid dose on treatment effect. We entered both items inthe 1 model and report results from this multivariate model.

ResultsA total of 20 trials of opioid analgesics (a total of 7295 partici-pants) were included in this review (see Table). Nineteen opi-oid analgesic trials evaluated participants with chronic low backpain, and 1 head-to-head trial evaluated participants with sub-acute low back pain. Seventeen RCTs compared an opioidanalgesic with placebo and 3 trials compared 2 opioid anal-gesics.29-31 None of the trials evaluated long-term use or out-comes, the maximum treatment period was 12 weeks, and themaximum follow-up was also 12 weeks. Seventeen of the 20trials reported industry funding. The medicines used in thesetrials were oral hydromorphone,32 oxymorphone,29,33,34

morphine,30,35 tramadol monotherapy31,36-38 or in combina-tion with paracetamol,31,39-41 tapentadol,42 oxycodone mono-therapy,42-44 oxycodone in combination with naloxone,45 ornaltrexone,44 transdermal buprenorphine,43,46,47 transder-mal fentanyl,30 and hydrocodone.48 The trials were typicallyof high quality with a mean (SD) PEDro score of 7.8 (1.5). ThePEDro ratings are summarized in eTable 2 in the Supplement.

Treatment Efficacy: Pain and Disability OutcomesPain OutcomesThere is moderate-quality evidence from 13 studies of chroniclow back pain (3419 participants) of an effect of single-ingredient opioid analgesics on pain in the short term; mean dif-ference (MD), −10.1 (95% CI, −12.8 to −7.4) (Figure 2). There ishigh-quality evidence from 6 studies (2605 participants) thatsingle-ingredient opioid analgesics relieve pain in the interme-diate term; MD, −8.1 (95% CI, −10.2 to −6.0). Combination opi-oid analgesics containing a simple analgesic showed moderateevidence of pain relief in the intermediate term; MD, −11.9 (95%CI, −19.3 to −4.4). Results from a single trial of the combinationof tramadol/paracetamol provided very low quality evidence ofpain relief for the short term; MD, −8 (95% CI, −16.2 to 0.2).41

The effects of single-ingredient and combination opioids wereminimal and approximately half the 20-point threshold for clini-cal importance. A funnel plot of standard error by treatment ef-fect for the short and intermediate term is shown in eFigures 1and 2 in the Supplement, respectively. The evidence for short-term efficacy was downgraded 1 level for publication bias (Eg-ger P= .007). There were no long-term outcomes data.

Disability OutcomesThere were limited data on disability outcomes. Results froma single trial showed no significant effect of the combinationof tramadol-paracetamol41 on disability for the short term; MD,−6.2 (95% CI, −8.5 to 20.9), and results from another singletrial40 of the tramadol-paracetamol combination showed nosignificant effect for the intermediate term; MD, −3.7 (−11.8 to4.4). The evidence from these trials is of very low quality.A single study of morphine35 showed no clinically significantreduction in disability for the short term; MD, −6.3 (95% CI,0.5-12.1), with the evidence being of very low quality.

See eTable 4 in the Supplement for overall grading of evi-dence and eTable 5 in the Supplement for morphine equiva-lent conversions.

Effect of Opioid Dose and Enrichment Study Designon Short-Term Treatment EfficacyIn the 13 RCTs evaluating short-term efficacy, the morphine-equivalent dose ranged from 40.0 mg to 242.7 mg per day.Seven of the 13 RCTs used an enrichment study design wherebyonly the participants who responded favorably to the studymedication, and tolerated the medicine in the trial run-in phase(prerandomization) were eligible to continue in the trial properand be randomized to the study treatment. Trial resultsgrouped by log opioid dose and enrichment study design areshown in Figure 3A and B, respectively. Results from the strati-fied analysis are shown in Figure 3C. The meta-regressionmodel, including log opioid dose and enrichment study de-sign, showed there was a significant effect of opioid dose ontreatment effect, with a 12.0 point greater pain relief for ev-ery 1 log unit increase in dose (P = .046) (ie, 10 mg of mor-phine equivalents). The model predicts that clinically impor-tant effects are not seen within the dose range evaluated(≤240-mg morphine equivalents per day). The effect of en-richment study design was not statistically significant (P = .69).Together, log morphine-equivalent dose and enrichment studydesign accounted for 11% of variance in treatment effect.

Results from the multivariate analysis exploring dichoto-mous dose and enrichment study design showed no statisti-cally significant effect of dose (P = .52) or enrichment studydesign (P = .40).

Treatment Discontinuation and Loss to Follow-upThe proportion of participants given an opioid analgesic whowere withdrawn from a trial owing to adverse events or lackof efficacy and the proportion lost to follow-up are shown inFigure 4 with more detailed information in eTable 6 in theSupplement. In the 8 trials (10 treatment contrasts) using anenrichment study design, only 20.3% to 48.4% remained inthe trial and contributed data to the efficacy estimate, and inthe nonenrichment study design this was 39.8% to 75.0%. Ir-respective of study design, the predominant causes for drop-out were adverse events or lack of efficacy, with half of trialshaving 50% of participants drop out owing to these 2 rea-sons. Even in the enrichment trials, where participants en-tered the trial only if they tolerated and responded to the medi-cine in the run-in phase, from 31.4% to 61.9% withdrew owingto adverse events and 3.3% to 29.6% withdrew owing to lackof efficacy in the randomized phase of the trial.

Eight trials32-34,37,38,40,42,47 provided details on the pro-portion of participants experiencing at least 1 adverse eventin the run-in and/or RCT phase. Overall, the median rates (in-terquartile range [IQR]) of adverse events in the RCT phase were49.1% (44.0%-55.0%) for placebo and 68.9.% (55.0%-85.0%)for treatment groups (risk ratio [RR], 1.3; P < .01). Common ad-verse events reported by participants in opioid analgesic trialsincluded central nervous system adverse events (headache,somnolence, dizziness), gastrointestinal tract adverse events(constipation, nausea, vomiting), and autonomic adverse

Research Original Investigation Effects of Opioid Analgesics for Low Back Pain

E4 JAMA Internal Medicine Published online May 23, 2016 (Reprinted) jamainternalmedicine.com

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/ by Paul Coelho on 05/23/2016

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

events, such as dry mouth. In some studies,33,34,38 over halfof participants who experienced an adverse event completedthe study. Studies rarely reported the severity or duration of

adverse events, therefore it was not possible to categorize ad-verse events based on severity (see eTables 7 and 8 in theSupplement).

Table. Characteristics of Included Studiesa

Source

PatientPopulationBaseline Setting Intervention Comparison

Length ofTreatment Follow-up

EligibleOutcomeMeasure(s)

IndustryFunding

Allanet al,30

2005

680 Patientswith chronic LBP;265 M, 415 F,mean age, 54.0 y

Multicenter Transdermal fentanyl,25 μg/h every 3 d,n = 338

Oral morphine,30 mg per 12 h,n = 342

13 mo 1 wk,13 mo

VAS Unclear

Buynaket al,42

2010

965 Patientswith chronic LBP;406 M, 559 F,mean age, 49.9 y

85 US centers15 Canadiancenters3 Australiancenters

Tapentadol(100-250 mg twicea day), n = 313 oroxycodone MR (20-50 mgtwice a day), n = 322

Placebo,n = 313

12 wk 1, 8, 12 wk NRS (meanNRS over 12-hperiod)

Yes

Chu,35

et al2012

139 Patientswith chronic LBP;78 M, 61 F,mean age, 41.9 y

Clinicalcenters,Stanford

Morphine mean endtitration dose, 78 mg/d,n = 48

Placebo, n = 55 1 mo 1 mo VAS (mean VASover preceding2 wk)

Unclear

Cloutieret al,45

2013

83 Patientswith chronic LBP;39 M, 44 F,mean age, 51.3 y

10 Canadiancenters

Combination controlledrelease tablet oxycodone,10 mg + naloxone, 5 mg(increasing to≤40 mg/20 mg) twice perday, n = 32

Placebo, n = 31 8 wk Week 8 VAS (mean VASover past mo)

Yes (PurduePharma)

Gordonet al,46

2010

79 Patients withchronic LBP; 31 M,47 F (1 unclear),mean age, 50.7 y

13 Canadiancenters

Transdermalbuprenorphine, 10 μg/h(max ≤40 μg/h) worn for6-8 d, n = 37

Placebotransdermalpatch, n = 42

8 wk 8 wk VAS (meandaily VAS)

Yes (PurduePharma)

Haleet al,32

2010

266 Patientswith chronic LBP;132 M, 134 F,mean age, 48.6 y

66 Centers inthe US

≥12 mg and ≤64 mghydromorphone MR/d,n = 133

Placebo,n = 133

12 wk 1, 8, 12 wk NRS Yes (EndoPharmaceuticals)

Haleet al29,2005

329 Patientswith chronic LBP;174 M, 155 F,mean age, 45.5 y

Clinical centersin the US

Oxymorphone MR79.4 mg/d, n = 71 oroxycodone MR,155 mg/d, n = 75

Placebo, n = 67 18 d Days 7 and18

VAS (measured4 h aftermorning dose)

Yes (EndoPharmaceuticals)

Haleet al,34

2007

142Opioid-experiencedpatients withchronic LBP; 78 M,64 F, mean age,47.1 y

30Multidisciplinarypain centers inthe US

Oxymorphone,20-260 mg/d, n = 70

Placebo, n = 72 3 mo Day 10,<3 mo

VAS (mean VASover past 24 h)

Yes (EndoPharmaceuticals)

Katzet al,33

2007

325 Patients withchronic LBP;216 M, 109 F,mean age, 49.8 y

Multicenter US Oxymorphone MR,39.2 mg/d (meanstabilized dose),n = 105

Placebo,n = 100

12 wk Weeks 1and 8, 90 d

VAS Yes (EndoPharmaceuticals)

Pelosoet al,39

2004

336 Patients withchronic LBP;126 M, 210 F,mean age, 57.5 y

US Combination tabletcontaining tramadol,36.5 mg + paracetamol,325 mg (max 8 doses/d),n = 167

Placebo,n = 169

91 d 91 d VAS (meanVAS within thepreceding 48 h)

Yes (Ortho-McNeilPharmaceuticals)

Perrotet al,31

2006

119 Patientswith subacute LBP;50 M, 69 F,mean age, 55.3 y

Multicenterin Germany

Combination tabletcontaining tramadol,37.5 mg + paracetamol,325 mg; max 8 doses/d,n = 51

Tramadol,50 mg,monotherapy;max, 8 doses/d,n = 48

10 d Day 10 VAS Yes (GrünenthalGmBH Aachen,Germany)

Raucket al,48

2014

510 Patientswith chronic LBP;235 M, 275 F,mean age, 49.0 y;NRS>4.0

59 Sites inthe US

Hydrocodone,20-100 mg every 12 h,n = 151

Placebo,n = 151

12 wk Day 85 NRS Yes (Zogenix)

Ruoffet al,40

2003

318 Patientswith chronic LBP;117 M, 201 F,mean age, 53.9 y;VAS ≥40 mm

29 Centersin the US

Combination tabletcontaining tramadol,37.5 mg + paracetamol,325 mg, 1-2 tablets4 times/d, n = 91

Placebo, 1-2tablets,4 times/d,n = 74

91 d 91 d VAS (mean VASover preceding48 h) RMDQ

Yes (Ortho-McNeilPharmaceuticals)

Schiphorstet al,41

2013

50 Participantswith chronic LBP;16 M, 34 F,mean age, 43.0 y;NRS ≥4.0

2 Rehabilitationcenters in theNetherlands

Combination tabletcontaining tramadol,37.5 mg + paracetamol,325 mg, 1-2 capsules≤3 times/d, n = 25

Placebo, n = 25 14 d 14 d VAS Grünenthal BVand StichtingBeatrixoord,The Netherlands

Schnitzeret al,36

2000

254 Patientswith chronic LBP;127 M, 127 F,mean age, 47.1 y

26 Centersin the US

Tramadol,200-400 mg/d,n = 127

Placebo,n = 127

4 wk 49 d VAS (meanVAS withinpreceding 24 h)RMDQ

Yes (Ortho-McNeilPharmaceuticals)

(continued)

Effects of Opioid Analgesics for Low Back Pain Original Investigation Research

jamainternalmedicine.com (Reprinted) JAMA Internal Medicine Published online May 23, 2016 E5

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/ by Paul Coelho on 05/23/2016

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Head-to-Head TrialsTreatment effects for head-to-head opioid analgesic trialsare shown in eFigure 3 in the Supplement. There was a sta-tistically significant difference in treatment outcomebetween different strengths of transdermal buprenorphinefor both the short and intermediate term, with the 20-μg/hpatch providing greater pain relief than the 5-μg/h patch(MD, 4.8 [95% CI, 0.6-9.0] and MD, 6.7 [95% CI, 2.3-11.2],respectively). Oxycodone, 40 mg per day, provided greaterpain relief than transdermal buprenorphine, 5-μg/h, for boththe short and intermediate term (MD, 5.9 [95% CI, 1.6-10.2]and MD, 7.6 [95% CI, 3.0-12.2], respectively). An evaluationof morphine equivalent conversions (eTable 5 in the Supple-ment) showed similar mean daily morphine equivalents forthese trials, providing a plausible explanation for the smalldifference.

DiscussionThis review has found that there is evidence that opioid an-algesics relieve pain in the short and intermediate term forpeople with chronic (but not acute) low back pain, but it is un-certain if they improve disability. Treatment effects are small,being half the threshold for clinical importance. The medi-

cines are also commonly associated with adverse events. Wefound some evidence of a greater effect of opioid analgesicswith larger doses; however, the effects are not likely to be clini-cally important even at high doses. A detailed analysis of drop-outs from trials revealed that under half of participants enter-ing these trials contributed to treatment effect size estimates.There is no evidence on long-term use and limited evidencefor acute low back pain.

The strengths of this review include a consideration of opi-oid dose and study design as well as a comprehensive searchstrategy covering single-ingredient and combination opioid an-algesics used to treat low back pain. The PEDro scale was usedto assess risk of bias because it has acceptably high clinomet-ric properties,18-20 whereas limitations have been reported forthe Cochrane risk of bias scale.49,50 Limitations of this reviewinclude possible publication bias, as only studies published inpeer-reviewed journals were included. A limitation of the meta-regression is that it does not account for variability in dose re-sponse as a result of duration of treatment or intrinsic factors(eg, genetic variability).

Our review challenges the prevailing view that opioidmedicines are powerful analgesics for low back pain. Opioidanalgesics had minimal effects on pain, and even at highdoses the magnitude of the effect is less than the acceptedthresholds for a clinically important treatment effect on pain.

Table. Characteristics of Included Studiesa (continued)

Source

PatientPopulationBaseline Setting Intervention Comparison

Length ofTreatment Follow-up

EligibleOutcomeMeasure(s)

IndustryFunding

Steineret al,43

2011

660 Patientswith chronic LBP;346 M, 314 F,mean age, 50.0 y

75 Centersin the US

Transdermalbuprenorphine, 20 μg/honce weekly, n = 176 ortransdermalbuprenorphine, 5 μg/honce weekly, n = 221 oroxycodone, 40 mg/d,n = 219

Oxycodone,40 mg/d ortransdermalbuprenorphine,20 μg/h onceweekly ortransdermalbuprenorphine,5 μg/h onceweekly

12 wk Weeks, 4,8, 12

0-10 Pointpain scale(mean painwithinpreceding 24 h)

Yes (PurduePharma)

Steineret al,47

2011

541 Patientswith chronic LBP;242 M, 298 F,mean age, 49.4 y

86 Centersin the US

Transdermalbuprenorphine, 10 μg/honce weekly, n = 257

Placebo,n = 283

84 d 8 wk 0-10 Pointpain scale(mean painwithinpreceding 24 h)

Yes (PurduePharma)

Uberallet al,37

2012

355 Patientswith chronic LBP;135 M, 220 F,mean age, 58.5 y

31 Sites inGermany

Tramadol MR, 200 mg/d,n = 107

Placebo,n = 110

6 wk 4 wk NRS (meanNRS withinpreceding 24 h)

Yes (TEVAGermany)

Vorsangeret al,38

2008

386 Patientswith chronic LBP,192 M, 194 F,mean age, 47.8 y;VAS ≥40 mm

30 Clinicalcenters inthe US

Tramadol MR, 300 mg/d,n = 127 or tramadol MR,200 mg/d, n = 129

Placebo,n = 126

12 wk 1, 8 and12 wk

VAS (meanVAS)

Yes (Biovail Corp)

Websteret al,44

2006

719 Patientswith chronic LBP;277 M, 442 F,mean age, 48.1 y

45 Sitesin the US

Oxycodone + low-dosenaltrexone 4 times/d(oxycodone34.5 mg/d + low-dosenaltrexone), n = 206 oroxycodone, 4 times/dn = 206 (39 mg/d) oroxycodone + low-dosenaltrexone twice a day,n = 206 (oxycodone,34.7 mg/d + low-dosenaltrexone)

Placebo n = 101 12 wk Weeks 1and 12

VAS (currentmean painintensity)

Unclear

a All treatments given orally unless otherwise indicated.Abbreviations: LBP, low back pain; max, maximum; MR, modified release form; NRS, Numeric Rating Scale; RMDQ, Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire;US, United States; VAS, visual analog scale.

Research Original Investigation Effects of Opioid Analgesics for Low Back Pain

E6 JAMA Internal Medicine Published online May 23, 2016 (Reprinted) jamainternalmedicine.com

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/ by Paul Coelho on 05/23/2016

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Importantly, the magnitude of the treatment effect weobserved is similar to that reported for NSAIDs vs placebo inthe Cochrane review of NSAIDs.51 This review focuses on themagnitude and clinical significance of treatment effects12,13

and presents a more detailed evaluation of run-in failure,treatment discontinuation, and loss to follow-up comparedwith existing reviews.7,9,10 Typically, the trials’ estimate oftreatment effect was derived from approximately 50% of par-ticipants who initially entered the trial, with participantswithdrawn mainly because they did not tolerate or respond tothe medicine. Taken together, these issues suggest therewould be much lower treatment effects among unselectedgroups of people new to these medicines.52

An unexpected finding of our study was that the use of anenrichment design was not associated with an exaggeratedtreatment effect. This result is in alignment with that of a studycomparing enriched and nonenriched trials of opioid analge-sics for chronic noncancer pain, in which it was similarly notedthat enriched study designs do not significantly influence theestimates of treatment efficacy.53

An important feature of this review is that we also con-ducted a metaregression to explore association between theopioid analgesic dose and treatment effect and found there isa 12.0-point increase in pain relief for every 1 log unitincrease in morphine-equivalent dose. Adjusting for use ofan enrichment design, the predicted treatment effect was a

Figure 2. Effects of Opioid Analgesics on Short-term and Intermediate-term Pain Outcomes

−30 0 20−10 10

Mean Difference (95% CI)

−20

Source

Short−term enrichment design

Dosage, mg

Opioid Placebo Mean Difference(95% CI)

FavorsOpioid

FavorsPlacebo Weight, %Mean (SD) Total Mean (SD) Total

Vorsanger et al,38 2008a 35 (26) 129 40 (25.9) 6340.0 −5.0 (−12.8 to 2.8) 5.4

Schnitzer et al,36 2000 35 (27.9) 127 51 (29.8) 12748.5 −16.0 (−23.1 to −8.9) 5.8

Vorsanger et al,38 2008b 34 (23.7) 127 40 (25.9) 6360.0 −6.0 (−13.6 to 1.6) 5.5

Katz et al,33 2007 33 (24.6) 105 45 (27.9) 100117.6 −12.0 (−19.2 to −4.8) 5.7

Rauck et al,48 2014 4.8 (15.6) 151 9.6 (15.5) 151119.0 −4.8 (−8.3 to −1.3) 8.3

Hale et al,32 2010 31 (19.4) 133 41 (18.8) 133152.0 −10.0 (−14.6 to −5.4) 7.6

Hale et al,29 2005a 6.5 (23.8) 75 27.5 (23.8) 33232.5 −21.0 (−30.7 to −11.3) 4.3

Hale et al,29 2005b 8.5 (23.9) 71 27.5 (23.8) 34238.2 −19.0 (−28.7 to −9.3) 4.3

Hale et al,34 2007 31 (16.8) 49 55 (15.4) 18242.7 −24.0 (−32.5 to −15.5) 4.9

Subtotal (95% CI) 722967 −12.4 (−16.9 to −7.9) 51.9Short−term nonenrichment design

Uberall et al,37 2012 −21 (20) 107 −20 (18) 11040 −1.0 (−6.1 to 4.1) 7.2

Webster et al,44 2006b 41 (25.1) 206 54 (28.7) 3351.8 −13.0 (−23.4 to −2.6) 4.0

Webster et al,44 2006a 42 (25.5) 206 54 (28.7) 3452.1 −12.0 (−22.4 to −1.7) 4.1

Cloutier et al,45 2013 48.6 (23.1) 32 55.9 (25.4) 3154.8 −7.3 (−19.3 to 4.7) 3.3

Webster et al,44 2006c 39 (25.3) 206 54 (28.7) 3458.5 −15.0 (−25.3 to −4.8) 4.1

Gordon et al,46 2010 40.9 (20.2) 37 48 (22.5) 4260.0 −7.1 (−16.5 to 2.3) 4.5

Chu et al,35 2012 −21.1 (15.9) 48 −12.5 (19.2) 5578.3 −8.6 (−15.4 to −1.8) 6.0

Buynak et al,42 2010a 46.2 (17.5) 171 53.8 (19) 8879.5 −7.6 (−12.4 to −2.8) 7.5

Buynak et al,42 2010b 47.4 (20.6) 201 53.8 (19) 89114.9 −6.4 (−11.3 to −1.5) 7.4

Subtotal (95% CI) 5161214 −7.3 (−10.0 to 4.6)Total (95% CI)

I2 = 64%

12382181 −10.1 (−12.8 to −7.4)

48.1100

Total (95% CI)

I2 = 16%

9081697 −8.1 (−10.2 to −6.0) 100

Intermediate−term enrichment design

Steiner et al,47 2011 38.1 (19.4) 257 43.9 (21.2) 28236.0 −5.8 (−9.2 to −2.4) 23.5

Vorsanger et al,38 2008a 38 (26) 129 39 (25.9) 6340.0 −1.0 (−8.8 to 6.8) 6.5

Vorsanger et al,38 2008b 33 (23.7) 127 39 (25.9) 6360.0 −6.0 (−13.6 to 1.6) 6.8

Katz et al,33 2007 31 (24.5) 105 47 (27.9) 100117.6 −16.0 (−23.0 to −8.8) 7.5

Hale et al,32 2010 32 (19.4) 133 41 (18.8) 133152.0 −9.0 (−13.6 to −4.4) 15.7

Subtotal (95% CI) 641751 −7.6 (−11.5 to −3.6) 60.1Intermediate−term nonenrichment design

Webster et al,44 2006b 42 (25.6) 206 52 (30.5) 3351.8 −10.0 (−21.0 to 1.0) 3.5

Webster et al,44 2006a 43 (25.5) 206 52 (30.5) 3452.1 −9.0 (−19.8 to 1.8) 3.6

Webster et al,44 2006c 40 (25.3) 206 52 (30.5) 3458.5 −12.0 (−22.8 to −1.2) 3.6

Buynak et al,42 2010a 46.2 (16.4) 145 55.1 (18.3) 8379.5 −8.9 (−13.7 to −4.1) 14.9

Buynak et al,42 2010b 46.4 (19.9) 183 55.1 (18.3) 83114.9 −8.7 (−13.6 to −3.8) 14.3

Subtotal (95% CI) 267946 −9.2 (−12.2 to −6.2) 39.9

Mean daily morphine equivalent dose in milligrams. Refer to eTable 5 in the Supplement for drug comparisons. Negative outcome values represent mean changefrom baseline. Egger P = .007 for short term and P = .42 for intermediate term.

Effects of Opioid Analgesics for Low Back Pain Original Investigation Research

jamainternalmedicine.com (Reprinted) JAMA Internal Medicine Published online May 23, 2016 E7

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/ by Paul Coelho on 05/23/2016

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

6.7-point increase in pain relief at 40-mg morphine equiva-lent units and a 16.1-point increase in pain relief at 240-mgmorphine equivalent units. The metaregression findings sug-gest that while increasing dose was associated with greatereffect, even at the higher doses the effect of opioid was lessthan the 20-point criterion we adopted for a clinically impor-tant effect. However, it is important to note that these aregroup mean differences, and some individuals may experi-ence meaningful pain relief from clinically used doseswhereas others may get very minimal relief or no relief at all.Concerns over adverse events and misuse continue to rise inline with the increased use and misuse of these medi-cines.11,54 However, despite the widespread use of opioidanalgesics there has been uncertainty about their clinicalbenefits for low back pain until now. This review dispels thecommon public misconception that opioid analgesics arepowerful analgesics, showing this is not the case for chroniclow back pain and that clinically significant pain relief is notlikely to be achieved at higher doses of opioid analgesics,which can be associated with potentially harmful effects(240-mg morphine equivalents per day).55 The latest reviewof opioid prescribing guidelines55 cautions against exceeding200 mg of morphine equivalents per day as a way of alleviat-ing the risk of opioid-related complications, such as life-threatening respiratory depression. Higher doses of opioidanalgesics have also been associated with misuse, physicaldependence, hyperalgesia, and clinically significant hor-monal changes.55-63 In 2010, there were 16 65164 opioid-related deaths reported in the United States. Of concern arethe paradoxical effects of opioid analgesics including opioid-induced hyperalgesia,65 a vexing issue thought to propagatethe cycle of misuse and dependency on these medications.There is currently no evidence to support the long-term useof opioid analgesics in low back pain at any dose. Our reviewhighlights the need to revise existing guidelines to acknowl-edge that (1) the effect of opioid analgesics in chronic lowback pain is modest and not likely to be clinically significantat recommended doses and (2) there is considerable uncer-tainty about long-term use of these medicines for back pain.

Previous reviews excluded studies that evaluated combi-nation medicine products containing opioid analgesics andsimple analgesics or opioid antagonists.9,10 The addition ofsimple analgesics to opioid analgesics may have synergisticeffects and potentially reduce the need for higher doses ofopioid analgesics.61-63,66 This review has found moderate-quality evidence that paracetamol combined with the weakopioid tramadol provides modest, but not clinically signifi-cant reduction in pain (but not disability). This result is simi-lar to findings from single-ingredient opioid analgesics.Another trial of the paracetamol-codeine combination66 notincluded in the pooled analysis of this review showed thatthere were significantly more people with chronic low backpain who experienced more than 30% pain relief in theparacetamol/tramadol group than the placebo group; how-ever, it was not possible to interpret the clinical significance ofthese effects.

Tramadol and tapentadol exhibit their analgesic effectsby 2 complementary pharmacological actions: binding to

Figure 3. Effect of Opioid Dose on Treatment Effect

20

10

0

−10

−26

−30

16

6

−6

−16

−20

−36

Y = 13.7 − 12.0 × log morphine equivalent dose − 1.2 if study design = enrichment

10

0

−10

−26

−30

16

6

−6

−16

−20

10

0

−10

−26

−30

16

6

−6

−16

−20

−401.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.62.5

Tre

atm

ent

Eff

ect

Log Morphine-Equivalent Dose

2.4

−36Nonenrichment Enrichment

Tre

atm

ent

Eff

ect

Study Design

−36<100 mg Morphine

Equivalents/d≥100 mg Morphine

Equivalents/d

Tre

atm

ent

Eff

ect

Regression of morphine dose on treatment effectA

Impact of study design on treatment effectB

Effect size and morphine equivalent doseC

A, Regression of log dose (morphine equivalents) on treatment effect forchronic low back pain; short-term pain relief; P = .046. B, Regression of studydesign on treatment effect; short-term pain relief; P = .69. Note circlesrepresent one opioid analgesic vs placebo comparison. Negative values favoropioid analgesic. C, Effect size estimates from cutoff dose less than 100 mgmorphine equivalents per day and greater than or equal to 100 mg morphineequivalents per day.

Research Original Investigation Effects of Opioid Analgesics for Low Back Pain

E8 JAMA Internal Medicine Published online May 23, 2016 (Reprinted) jamainternalmedicine.com

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/ by Paul Coelho on 05/23/2016

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

μ-opioid receptors, and inhibition of reuptake of noradrena-line and serotonin.67,68 Based on these known pharmaco-logical properties, tramadol and tapentadol are widelyregarded as synthetic analgesic with opioid-like effects(World Health Organization Anatomical Therapeutic Chemi-cal code N02AX02 and N02AX06, respectively, within theN02A class) and, as such, were included in the analysis asopioid analgesics.

Very few opioid analgesic trials reported on global recov-ery outcomes, and the effects on disability, where reported inthis review, were small. Even with short-term use, there is nosubstantive reduction in disability. It is important to considerlong-term functional outcomes with these medicines be-cause a reduction in pain alone may not be correlated with im-proved disability outcomes. It is possible that the combina-tion with nonpharmacological treatment strategies, such asphysical activity, may have a synergistic effect and future re-search should focus on evaluating the benefits of such an ap-

proach. While this review suggests that opioid analgesics pro-vide pain relief which is comparable to the effects reported inprevious reviews of NSAIDs, head-to-head comparisons wouldyield valuable insight into effective dose regimens and choiceof medicine.

ConclusionsIn people with chronic low back pain, opioid analgesics pro-vide short and/or intermediate pain relief, though the effectis small and not clinically important even at higher doses. Manytrial patients stopped taking the medicine because they did nottolerate or respond to the medicine. There is no evidence onopioid analgesics for acute low back pain or to guide pro-longed use of these medicines in the treatment of people withchronic low back pain.

ARTICLE INFORMATION

Published Online: May 23, 2016.doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.1251.

Author Affiliations: The George Institute for GlobalHealth, Sydney, Australia (Abdel Shaheed,

McLachlan); School of Medicine, Western SydneyUniversity, Penrith, Australia (Abdel Shaheed);Musculoskeletal Division, The George Institute forGlobal Health, Sydney, Australia (Maher); SydneyMedical School, University of Sydney, Sydney,

Australia (Maher); Discipline of Pharmacy, GraduateSchool of Health, University of Technology Sydney,Sydney, Australia (Williams); Department of ClinicalPharmacology, St Vincent’s Hospital andSt Vincent’s Clinical School, University of New

Figure 4. Percentage of Trial Participants Receiving an Opioid Analgesic Who Dropped out of the TrialDuring the Run-in and Trial Phases and the Percentage Who Remained to Contribute Data to the TreatmentEffect Estimate

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

Hale et a

l,29 2

005a

Hale et a

l,29 2

005b

Schnitz

er et a

l,36 2

000

Rauck et a

l,48 2

014

Katz et a

l,33 2

007

Hale et a

l,34 2

007

Vorsanger e

t al,38 2

008a

Vorsanger e

t al,38 2

008b

Stein

er et a

l,47 2

011a

Hale et a

l,32 2

010

Buynak et al,42 2

010a

Webst

er et a

l,44 2

006b

Per

cen

tag

e

Schip

horst e

t al,41 2

013

Cloutie

r et a

l,45 2

013

Uberall

et al,37 2

012

Chu et al,35 2

012

Ruoff et a

l,40 2

003

Buynak et al,42 2

010b

Peloso

et al,39 2

004

Gordon et a

l,46 2

010

Webst

er et a

l,44 2

006c

Webst

er et a

l,44 2

006a

Run-in phase: dropped out due to adverse events or lack of efficacy

Run-in phase: dropped out due to loss to follow up

Trial phase: dropped out due to adverse events or lack of efficacy

Trial phase: dropped out due to loss to follow up

Contributes to efficacy estimate

Loss to follow-up includes patientswithdrawn from trial owing tononcompliance, patients electing towithdraw, patients without completeoutcomes, and various other reasons.

Effects of Opioid Analgesics for Low Back Pain Original Investigation Research

jamainternalmedicine.com (Reprinted) JAMA Internal Medicine Published online May 23, 2016 E9

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/ by Paul Coelho on 05/23/2016

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

South Wales, Sydney, Australia (Day); School ofMedical Sciences, University of New South Wales,Sydney, Australia (Day); Centre for Education andResearch on Ageing, Sydney, Australia (McLachlan).

Author Contributions: All authors approved thefinal version of the article. Dr Abdel Shaheed hadaccess to all of the data in the study and takesresponsibility for the integrity of the data and theaccuracy of the data analysis.Study concept and design: Abdel Shaheed, Maher,Williams, McLachlan.Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data:Abdel Shaheed, Day, McLachlan.Drafting of the manuscript: Abdel Shaheed, Maher,McLachlan.Critical revision of the manuscript for importantintellectual content: All authors.Statistical analysis: Abdel Shaheed, Maher.Administrative, technical, or material support:Maher, McLachlan.Study supervision: Maher, Williams, Day, McLachlan.Other: Abdel Shaheed.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Drs McLachlan,Maher, and Day are investigators on 3 trialsevaluating medicines for low back pain.

Funding/Support: Dr Maher is funded by aresearch fellowship from the National Health andMedical Research Council of Australia. DrMcLachlan is the Program Director on the NationalHealth and Medical Research Council of AustraliaCentre for Research Excellence on Medicines andAgeing.

Additional Contributions: We Thank NathanielKatz, MD for assisting with our data request. Wealso thank Ms Patricia Parreira, BA for providingtranslation. They were not compensated for theircontributions.

REFERENCES

1. Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, et al. Years livedwith disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematicanalysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2163-2196.

2. Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, et al. A comparativerisk assessment of burden of disease and injuryattributable to 67 risk factors and risk factorclusters in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematicanalysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2224-2260.

3. Deyo RA, Smith DHM, Johnson ES, et al. Opioidsfor back pain patients: primary care prescribingpatterns and use of services. J Am Board Fam Med.2011;24(6):717-727.

4. Hudson TJ, Edlund MJ, Steffick DE, Tripathi SP,Sullivan MD. Epidemiology of regular prescribedopioid use: results from a national, population-basedsurvey. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;36(3):280-288.

5. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare(AIHW) Medications prescribed for back pain(2009) Available at https://www.aihw.gov.au/back-problems/treatment-with-medications/. AccessedJanuary 21, 2013.

6. Williams CM, Maher CG, Hancock MJ, et al. Lowback pain and best practice care: A survey ofgeneral practice physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(3):271-277.

7. Deyo RA, Von Korff M, Duhrkoop D. Opioids forlow back pain. BMJ. 2015;350:g6380.

8. Chou R, Turner JA, Devine EB, et al. Theeffectiveness and risks of long-term opioid therapyfor chronic pain: a systematic review for a NationalInstitutes of Health Pathways to PreventionWorkshop. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(4):276-286.

9. Chaparro LE, Furlan AD, Deshpande A,Mailis-Gagnon A, Atlas S, Turk DC. Opioidscompared to placebo or other treatments forchronic low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.2013;8:CD004959.

10. Chaparro LE, Furlan AD, Deshpande A,Mailis-Gagnon A, Atlas S, Turk DC. Opioidscompared with placebo or other treatments forchronic low back pain: an update of the CochraneReview. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2014;39(7):556-563.

11. Roxburgh A, Bruno R, Larance B, Burns L.Prescription of opioid analgesics and related harmsin Australia. Med J Aust. 2011;195(5):280-284.

12. Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Wyrwich KW, et al.Interpreting the clinical importance of treatmentoutcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACTrecommendations. J Pain. 2008;9(2):105-121.

13. Ostelo RWJG, Deyo RA, Stratford P, et al.Interpreting change scores for pain and functionalstatus in low back pain: towards internationalconsensus regarding minimal important change.Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33(1):90-94.

14. Martell BA, O’Connor PG, Kerns RD, et al.Systematic review: opioid treatment for chronicback pain: prevalence, efficacy, and associationwith addiction. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(2):116-127.

15. van Tulder MW, Touray T, Furlan AD, Solway S,Bouter LM; Cochrane Back Review Group. Musclerelaxants for nonspecific low back pain:a systematic review within the framework of theCochrane collaboration. Spine (Phila Pa 1976).2003;28(17):1978-1992.

16. World Health Organisation Collaborating Centrefor Drugs Statistics Methodology. Internationallanguage for drug utilisation research (2011). http://www.whocc.no/. Accessed January 21, 2014.

17. Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook forsystematic reviews of interventions, version 5.0.2.Cochrane Collaboration; 2009.

18. de Morton NA. The PEDro scale is a validmeasure of the methodological quality of clinicaltrials: a demographic study. Aust J Physiother.2009;55(2):129-133.

19. Macedo LG, Elkins MR, Maher CG, Moseley AM,Herbert RD, Sherrington C. There was evidence ofconvergent and construct validity of PhysiotherapyEvidence Database quality scale for physiotherapytrials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(8):920-925.

20. Maher CG, Sherrington C, Herbert RD, MoseleyAM, Elkins M. Reliability of the PEDro scale forrating quality of randomized controlled trials. PhysTher. 2003;83(8):713-721.

21. Hjermstad MJ, Fayers PM, Haugen DF, et al;European Palliative Care Research Collaborative(EPCRC). Studies comparing Numerical RatingScales, Verbal Rating Scales, and Visual AnalogueScales for assessment of pain intensity in adults:a systematic literature review. J Pain SymptomManage. 2011;41(6):1073-1093.

22. Roland M, Fairbank J. The Roland-MorrisDisability Questionnaire and the Oswestry DisabilityQuestionnaire. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(24):3115-3124.

23. Comprehensive Meta-Analysis. http://www.meta-analysis.com/index.php. Accessed January21, 2014.

24. Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, et al; GRADEWorking Group. Grading quality of evidence andstrength of recommendations. BMJ. 2004;328(7454):1490.

25. Pinto RZ, Maher CG, Ferreira ML, et al. Drugsfor relief of pain in patients with sciatica: systematicreview and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;344:e497.

26. Furlan AD, Malmivaara A, Chou R, et al;Editorial Board of the Cochrane Back, Neck Group.2015 Updated Method Guideline for SystematicReviews in the Cochrane Back and Neck Group.Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2015;40(21):1660-1673.

27. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, MinderC. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple,graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629-634.

28. Boudreau D, Von Korff M, Rutter CM, et al.Trends in long-term opioid therapy for chronicnon-cancer pain. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf.2009;18(12):1166-1175.

29. Hale ME, Dvergsten C, Gimbel J. Efficacy andsafety of oxymorphone extended release in chroniclow back pain: results of a randomized, double-blind,placebo- and active-controlled phase III study. J Pain.2005;6(1):21-28.

30. Allan L, Richarz U, Simpson K, Slappendel R.Transdermal fentanyl versus sustained release oralmorphine in strong-opioid naïve patients withchronic low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30(22):2484-2490.

31. Perrot S, Krause D, Crozes P, Naïm C;GRTF-ZAL-1 Study Group. Efficacy and tolerability ofparacetamol/tramadol (325 mg/37.5 mg)combination treatment compared with tramadol(50 mg) monotherapy in patients with subacutelow back pain: a multicenter, randomized,double-blind, parallel-group, 10-day treatmentstudy. Clin Ther. 2006;28(10):1592-1606.

32. Hale M, Khan A, Kutch M, Li S. Once-daily OROShydromorphone ER compared with placebo inopioid-tolerant patients with chronic low back pain.Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(6):1505-1518.

33. Katz N, Rauck R, Ahdieh H, et al. A 12-week,randomized, placebo-controlled trial assessing thesafety and efficacy of oxymorphone extendedrelease for opioid-naive patients with chronic lowback pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23(1):117-128.

34. Hale ME, Ahdieh H, Ma T, Rauck R;Oxymorphone ER Study Group 1. Efficacy and safetyof OPANA ER (oxymorphone extended release) forrelief of moderate to severe chronic low back pain inopioid-experienced patients: a 12-week, randomized,double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Pain.2007;8(2):175-184.

35. Chu LF, D’Arcy N, Brady C, et al. Analgesictolerance without demonstrable opioid-inducedhyperalgesia: a double-blinded, randomized,placebo-controlled trial of sustained-releasemorphine for treatment of chronic nonradicularlow-back pain. Pain. 2012;153(8):1583-1592.

36. Schnitzer TJ, Gray WL, Paster RZ, Kamin M.Efficacy of tramadol in treatment of chronic lowback pain. J Rheumatol. 2000;27(3):772-778.

37. Uberall MA, Mueller-Schwefe GHH, Terhaag B.Efficacy and safety of flupirtine modified release forthe management of moderate to severe chronic lowback pain: results of SUPREME, a prospective

Research Original Investigation Effects of Opioid Analgesics for Low Back Pain

E10 JAMA Internal Medicine Published online May 23, 2016 (Reprinted) jamainternalmedicine.com

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/ by Paul Coelho on 05/23/2016

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

randomized, double-blind, placebo- andactive-controlled parallel-group phase IV study. CurrMed Res Opin. 2012;28(10):1617-1634.

38. Vorsanger GJ, Xiang J, Gana TJ, Pascual ML,Fleming RR. Extended-release tramadol (tramadolER) in the treatment of chronic low back pain.J Opioid Manag. 2008;4(2):87-97.

39. Peloso PM, Fortin L, Beaulieu A, Kamin M,Rosenthal N; Protocol TRP-CAN-1 Study Group.Analgesic efficacy and safety of tramadol/acetaminophen combination tablets (Ultracet) intreatment of chronic low back pain: a multicenter,outpatient, randomized, double blind, placebocontrolled trial. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(12):2454-2463.

40. Ruoff GE, Rosenthal N, Jordan D, Karim R,Kamin M; Protocol CAPSS-112 Study Group.Tramadol/acetaminophen combination tablets forthe treatment of chronic lower back pain:a multicenter, randomized, double-blind,placebo-controlled outpatient study. Clin Ther.2003;25(4):1123-1141.

41. Schiphorst Preuper HR, Geertzen JHB, vanWijhe M, et al. Do analgesics improve functioning inpatients with chronic low back pain? an explorativetriple-blinded RCT. Eur Spine J. 2014;23(4):800-806.

42. Buynak R, Shapiro DY, Okamoto A, et al.Efficacy and safety of tapentadol extended releasefor the management of chronic low back pain:results of a prospective, randomized, double-blind,placebo- and active-controlled Phase III study.Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010;11(11):1787-1804.

43. Steiner D, Munera C, Hale M, Ripa S, Landau C.Efficacy and safety of buprenorphine transdermalsystem (BTDS) for chronic moderate to severe lowback pain: a randomized, double-blind study. J Pain.2011;12(11):1163-1173.

44. Webster LR, Butera PG, Moran LV, Wu N, BurnsLH, Friedmann N. Oxytrex minimizes physicaldependence while providing effective analgesia:a randomized controlled trial in low back pain. J Pain.2006;7(12):937-946.

45. Cloutier C, Taliano J, O’Mahony W, et al.Controlled-release oxycodone and naloxone in thetreatment of chronic low back pain:a placebo-controlled, randomized study. Pain ResManag. 2013;18(2):75-82.

46. Gordon A, Rashiq S, Moulin DE, et al.Buprenorphine transdermal system for opioidtherapy in patients with chronic low back pain. PainRes Manag. 2010;15(3):169-178.

47. Steiner DJ, Sitar S, Wen W, et al. Efficacy andsafety of the seven-day buprenorphine transdermalsystem in opioid-naïve patients with moderate tosevere chronic low back pain: an enriched,randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlledstudy. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;42(6):903-917.

48. Rauck RL, Nalamachu S, Wild JE, et al.Single-entity hydrocodone extended-releasecapsules in opioid-tolerant subjects withmoderate-to-severe chronic low back pain:a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlledstudy. Pain Med. 2014;15(6):975-985.

49. Armijo-Olivo S, Stiles CR, Hagen NA, BiondoPD, Cummings GG. Assessment of study quality forsystematic reviews: a comparison of the CochraneCollaboration Risk of Bias Tool and the EffectivePublic Health Practice Project Quality AssessmentTool: methodological research. J Eval Clin Pract.2012;18(1):12-18.

50. Hartling L, Ospina M, Liang Y, et al. Risk of biasversus quality assessment of randomised controlledtrials: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2009;339:b4012.

51. Roelofs PD, Deyo RA, Koes BW, et al.Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for low backpain: an updated Cochrane review. Spine. 2008;33(16):1766-1774.

52. Temple R. Enrichment design may enhancesignals of effectiveness. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/NewsEvents/ucm295054.htm. Accessed January28, 2014.

53. Furlan A, Chaparro LE, Irvin E, Mailis-Gagnon A.A comparison between enriched and nonenrichedenrollment randomized withdrawal trials of opioidsfor chronic noncancer pain. Pain Res Manag. 2011;16(5):337-351.

54. Compton WM, Volkow ND. Major increases inopioid analgesic abuse in the United States:concerns and strategies. Drug Alcohol Depend.2006;81(2):103-107.

55. Nuckols TK, Anderson L, Popescu I, et al.Opioid prescribing: a systematic review and criticalappraisal of guidelines for chronic pain. Ann InternMed. 2014;160(1):38-47.

56. Benyamin R, Trescot AM, Datta S, et al. Opioidcomplications and side effects. Pain Physician.2008;11(2)(suppl):S105-S120.

57. Cicero TJ, Inciardi JA, Adams EH, et al. Rates ofabuse of tramadol remain unchanged with the

introduction of new branded and generic products:results of an abuse monitoring system, 1994-2004.Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14(12):851-859.

58. Cicero TJ, Inciardi JA, Muñoz A. Trends in abuseof OxyContin and other opioid analgesics in theUnited States: 2002-2004. J Pain. 2005;6(10):662-672.

59. Daniell HW. Hypogonadism in men consumingsustained-action oral opioids. J Pain. 2002;3(5):377-384.

60. Lee C, Ludwig S, Duerksen D. Low serumcortisol associated with opioid use: case report andreview of the literature. Endocrinologist. 2002;12(1):5-8.

61. American Pain Society. Principles of AnalgesicUse in the Treatment of Acute Pain and Cancer Pain.5th ed. Glenview, IL: American Pain Society; 2003.

62. Raffa RB. Pharmacology of oral combinationanalgesics: rational therapy for pain. J Clin PharmTher. 2001;26(4):257-264.

63. World Health Organisation. Cancer Pain Relief,With a Guide to Opioid Availability. Geneva,Switzerland: World Health Organisation; 1996:1-63.

64. Dart RC, Surratt HL, Cicero TJ, et al. Trends inopioid analgesic abuse and mortality in the UnitedStates. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(3):241-248.

65. Lee M, Silverman SM, Hansen H, Patel VB,Manchikanti L. A comprehensive review ofopioid-induced hyperalgesia. Pain Physician. 2011;14(2):145-161.

66. Lee JH, Lee CS; Ultracet ER Study Group.A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled,parallel-group study to evaluate the efficacy andsafety of the extended-release tramadolhydrochloride/acetaminophen fixed-dosecombination tablet for the treatment of chronic lowback pain. Clin Ther. 2013;35(11):1830-1840.

67. Tzschentke TM, Christoph T, Schröder W, et al.[Tapentadol: with two mechanisms of action in onemolecule effective against nociceptive andneuropathic pain. Preclinical overview]. Schmerz.2011;25(1):19-25.

68. Angeletti C, Guetti C, Paladini A, Varrassi G.Tramadol extended-release for the management ofpain due to osteoarthritis. ISRN Pain. 2013;2013;(16).

Effects of Opioid Analgesics for Low Back Pain Original Investigation Research

jamainternalmedicine.com (Reprinted) JAMA Internal Medicine Published online May 23, 2016 E11

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/ by Paul Coelho on 05/23/2016