OPINION Report card on Asean economic integration · overripe office vixen who seduc-es her married...

Transcript of OPINION Report card on Asean economic integration · overripe office vixen who seduc-es her married...

By MAUREEN DOWD

MONICA Lewinskysays she wouldmeet me for adrink.

I’m game.In her new meditation in Vani-

ty Fair, Monica mashes Haw-thorne and Coleridge, proclaim-ing that she’s ready to rip off her“scarlet-A albatross”, “reimag-ine” her identity and reclaim hernarrative.

At long last, she says, shewants to “burn the beret andbury the blue dress” and get un-stuck from “the horrible image”of an intern who messed aroundwith the president in the pantryoff the Oval Office, spilled the de-tails to the wrong girlfriend andsparked a crazy impeachmentscandal. I wish her luck.

Though she’s striking yet an-other come-hither pose in themagazine, there’s somethingpoignant about a 40-year-oldfrozen like a fly in amber forsomething reckless she did in her20s, while the unbreakable Clin-tons bulldoze ahead.

Besides, with the Clinton res-toration barrelling towards usand stretching as far as the eyecan see to President Chelsea, wecould all use a drink.

The last time I encounteredMonica was at the Bombay Club,a restaurant nestled between myoffice and the White House.

It was at the height of the im-peachment madness, and shewas drinking a Cosmo at a tablewith her family. After requestingthat the piano player play “Sendin the clowns”, she leaned inwith me, demanding to knowwhy I wrote such “scathing” piec-es about her.

My columns targeted the pant-ing Peeping Tom Ken Starr andthe Clintons and their hench-men, for their wicked attempt toprotect the First Couple’s politi-cal viability by smearing the in-tern as a nutty and slutty stalker.

I did think Monica could skipposing for cheesecake photos inVanity Fair while in the middleof a plea bargain.

But I felt sorry for her. Shehad propelled herself into thatmost loathed stereotype (exceptby Helen Gurley Brown): theoverripe office vixen who seduc-

es her married boss. Feministsturned on her to protect a presi-dent with progressive policies onwomen. Monica bristled withconfidence when she talked tome, but then she retreated to theladies’ room and had a meltdownon her cellphone with JudySmith.

Smith would go on to fameand fortune as a co-executiveproducer on Scandal, which fo-cuses on Kerry Washington’s Ol-ivia Pope, a blend of Judy, whowas a crisis manager, and her cli-ent Monica, who had an affairwith the president.

Washington journalistsfawned over the stars of Scandallast weekend at the White HouseCorrespondents’ Dinner festivi-ties, which served mainly as a

promotional vehicle for the ABCshow and HBO’s Veep.

The plot of Scandal is so lurid-ly over-the-top, it makes the sa-ga of the pizza-bearing internwho inspired it seem almostquaint.

You’d think that the bookMonica’s Story, the HBO docu-mentary, Barbara Walters’ inter-view and the 1998 Vanity Fairspread would be enough aboutthe most covered affair in histo-ry. Heck, the seamy Starr reportwas enough.

But she must feel that her reti-cence over the last 10 years of“self-searching and therapy” hasled the public to hunger for herthoughts on the eve of Hillary’sbook rollout next month and at amoment when President BarackObama is struggling to pull focusback from the Clintons, whose

past and future are more domi-nant than his present. Monica isin danger of exploiting her ownexploitation as she dishes about acouple whose erotic lives are ofwaning interest to the country.

But, clearly, she was stungand wanted to have her sayabout the revelation in Februarythat Hillary had told her friendDiane Blair, knowing it would bemade public eventually, that Billwas at fault for the affair but de-served props for trying to “man-age someone who was clearly anarcissistic loony toon”.

Hillary also said she blamedherself for Bill’s dalliance. Moni-ca trenchantly notes about thefeminist icon, who is playing thegender card on the trail this timearound: “I find her impulse toblame the Woman – not only mebut herself – troubling.” She alsosays that Bill “took advantage”of her – in a consensual way.

“Any ‘abuse’ came in the after-math,” she writes, “when I wasmade a scapegoat in order to pro-tect his powerful position”.

Disingenuously and preten-tiously, Monica says that thetragedy of Rutgers freshmanTyler Clementi, who committedsuicide in 2010 after his room-mate secretly streamed his liai-son with another man over theWeb, had wrought “a Prufrocki-an moment”: Did she dare dis-turb the Clinton universe to be-come a spokesman against bully-ing?

Her bullies are crude stran-gers in person and online who re-duce her to a dirty joke or verb.Monica corrects Beyonce, whosings, “He Monica Lewinsky’dall on my gown,” saying itshould be “He Bill Clinton’d allon my gown”.

But her bullies are also theClintons and their vicious attackdogs who worked so hard to turn“that woman”, as Bill so coldlycalled her, into the scapegoat.

As Hillary gave a cam-paign-style speech in Marylandon Tuesday, warning that eco-nomic inequality could lead to“social collapse”, That Womanstarted her own campaign, keen-ing about her own social col-lapse. It was like a Golden Oldietour of a band you didn’t want tohear in the first place.NEW YORK TIMES

This is a monthly series bythe NUS EconomicsDepartment. Each month, apanel will address a topicalissue. If you have a burningquestion on economics, writein to [email protected] “Ask NUS” in thesubject field.

S.E.A. View is a weeklycolumn on South-east Asianaffairs. Read more S.E.A.View pieces online atstraitstimes.com/news/opinion

IS ASEAN’S economic inte-gration encouraging the re-gion to become a more dis-tinctive collective entity inthe global economy? The an-

swer is yes, although with impor-tant reservations.

South-east Asia is an area of ex-treme economic diversity. Thegap in living standards betweenthe richest and poorest countries(Singapore and Myanmar respec-tively) is 40 to 1. But this is onlyone dimension.

Singapore is a services-basedeconomy; Brunei is oil-based; Ma-laysia and Thailand are fast indus-trialisers; Thailand and Vietnamare big agricultural exporters; In-donesia and the Philippines arenet food importers; and Cambo-dia, Laos and Myanmar are stillagrarian societies.

Government economic policiesalso vary widely. Singapore is afree port in which the total valueof trade is equal to 400 per centof gross domestic product. At theother extreme, Myanmar has onlyrecently started to open up its bor-ders. The value of trade in the lat-ter is equal to only 31 per cent ofGDP.

Then there are huge gaps in the

quality of regulation, institutionsand the business climate. Accord-ing to the World Bank, Singaporeranks first in the world for “easeof doing business”; Malaysia andThailand are in the top 20; but theothers are way behind.

Compounding such economicdiversity are wide differences inhistory, culture, geography, popu-lation, population density and –not least – political systems.

Nevertheless, there are also in-creasingly important elements ofconvergence across Asean coun-tries.

Integration with the globaleconomy stands out: Since the1980s, all Asean countries have lib-eralised trade and foreign direct in-vestment.

Average import-weighted tar-iffs are around 5 per cent for mostAsean countries. And all except In-donesia, Philippines, Laos and My-anmar have trade-to-GDP ratiosof about 100 per cent or higher.

Asean has also become a region-al production hub for parts andcomponents in global manufactur-ing supply chains. This has knit-ted Asean and North-east Asia –including China – together in ev-er-tighter trade and productionlinkages.

Now turn to the regional eco-nomic outlook. The InternationalMonetary Fund forecasts growthat 5 per cent this year for theAsean-5, which consists of thePhilippines, Indonesia, Malaysia,Thailand and Vietnam – a figurethat is in line with growth in thelast few years.

A slightly stronger recovery in

advanced economies, particularlyin the United States, should alsogive a marginal boost to Asean’sgrowth through exports.

Challenges ahead

BUT there are storm cloudsahead. First, a slowdown in Chi-na’s growth has implications forAsean’s exports of intermediateproducts in global supply chains,its exports destined for the Chi-nese domestic market, and Chi-nese investments in Asean.

Second, Asean countries haveseen a credit explosion as a resultof loose monetary policies athome and around the world. Con-sumer debt has piled up. Assetand property bubbles are gettingbigger.

Tighter global monetary condi-tions, especially with “tapering”by the US Federal Reserve and thelikelihood of higher interest ratesin the West, increase the risk of amini-crash.

Governments will have to bitethe political bullet and wean them-selves off loose-money policiessooner rather than later.

That said, Asean countries arein a much better position to weath-

er global shocks than they wereduring the Asian financial crisis in1997.

Fiscal and monetary conditionsare better, exchange rates aremore flexible, there is much lessexposure to short-term foreigndebt, and bond markets are deep-er.

Third, a decade of cheap-mon-ey policies and high commodityprices has engendered lazy com-placency in emerging markets.Asean is no exception.

Governments have neglectedstructural reforms to reduce mar-ket distortions. These are nowmore visible with tighter globalmonetary conditions and fallingcommodity prices.

Large swathes of markets forland, labour and capital remain un-reformed. That is also true ofmuch of the public sector. The lib-eralisation of international tradeand investment has slowed downor stalled.

Government red tape plaguesthe business climate.

The World Bank’s Doing Busi-ness Index has Vietnam in 99thplace, Myanmar bringing up therear in 182nd place, with Philip-pines, Indonesia, Cambodia and

Laos in between.

New opportunities

MOST Asean countries need freshstructural reforms not only tocope better with external shocks,but also to take advantage ofemerging trends in global supplychains. Multinationals are lookingfor new investment destinationsas China becomes more expen-sive.

If South Asia – India in particu-lar – opens up more to global mar-kets, labour-intensive, export-ori-ented manufacturing will migratethere.

That will present huge opportu-nities for Asean countries in themiddle of pan-Asian regional pro-duction networks, halfway be-tween China and India.

Genuine Asean economic inte-gration – the free flow of goods,services, capital and people with-in the region – would deliver hugegains, not least from deeper inte-gration into global supply chains.That is the logic of the Asean Eco-nomic Community (AEC).

The bulk of intra-regional tar-iffs have been abolished. Partialprogress has been achieved on sim-

plifying and harmonising Cus-toms procedures, cross-border in-frastructure projects, and openingup Asean skies to low-cost air-lines. A few sub-regional integra-tion initiatives have made head-way, notably the Greater MekongSub-Region and Iskandar-Singa-pore.

Asean EconomicCommunity

BUT, overall, the AEC is well be-hind its targets to reduce and abol-ish non-tariff and regulatory barri-ers in goods, services and invest-ment.

Most restrictions to intra-re-gional commerce lie here, not intariffs and quotas “at the border”.Moreover, Asean’s monetary andfinancial integration is even weak-er than it is in trade and invest-ment, so far restricted to modestmeasures like the Chiang Mai Initi-ative.

Incremental progress, not a uto-pian leap to European Un-ion-style top-down, institu-tion-heavy integration, is proba-bly the best Asean can expect, giv-en the political realities.

South-east Asia has made sub-stantial economic progress be-cause its governments have liberal-ised markets, thereby enabling in-tegration into global supplychains.

Now a second generation ofmarket reforms is needed to copewith external shocks and to takeadvantage of new regional and glo-bal opportunities.

Asean’s collective efforts canat best be a helpful auxiliary, butsuccess is mainly a matter of uni-lateral action by governments indi-vidually. Should these politicallychallenging reforms be implement-ed, Asean will become an evenmore distinctive and prosperouscollective entity in the global econ-omy.

[email protected] author is visiting associateprofessor at the Lee Kuan Yew School ofPublic Policy, National University ofSingapore.

By RAZEEN SALLYFOR THE STRAITS TIMES

S.E.A. VIEW

Monica is indanger ofexploiting her ownexploitation as shedishes about acouple whoseerotic lives are ofwaning interest tothe country.

ST Opinion online

By SURESH DE MELFOR THE STRAITS TIMES

L How do you assess thewell-being of a country?

THERE are many measures andrankings of well-being in circula-tion. For example, Singaporeranks among the top six econo-mies of the world in terms of in-come per capita. And according tothe 2013 Human Development Re-port and the 2013 World Happi-ness Report, both published bythe United Nations, Singapore isplaced 18th and 30th respectively.

What do these different mea-sures mean? Let us begin with theeconomic dimension. Within thefield of economics, gross domesticproduct (GDP) has become thestandard metric of economicwell-being. GDP measures thetotal value of goods and servicesproduced within a country duringa specified period. It also indicatesthe total income earned within acountry’s borders.

To compare across countries,GDP is usually expressed in pur-chasing power parity dollars (totake into account price differencesacross countries) and in per capitaterms (to reflect an average stand-ard of living in a country). The sis-ter measure, gross national prod-uct (GNP), is the total value ofgoods and services produced in aspecified period by the nationalsof a country. Unlike GDP, whichdefines production based on geo-graphical location, GNP accountsfor production based on owner-ship of the production inputs.

The twin measures of GDP andGNP arose out of the work of econ-omists Simon Kuznets and Rich-ard Stone, who developed the sys-tem of national accounting in the1930s. These were formally adopt-ed by the International MonetaryFund and the World Bank in the1940s. Although the initial empha-sis was on GNP, the focus shiftedto GDP in the 1980s.

GDP and GNP, as measures ofsuccess and well-being, have sev-eral limitations. They leave outnon-market transactions (for ex-ample, unpaid household work orchild care), do not distinguish be-tween market transactions that in-crease versus decrease well-being(for instance, building schools ver-sus prisons) and ignore sustainabil-ity issues (for example, cuttingdown forests). The measures donot adequately capture other im-portant aspects of well-being ei-ther, such as education, health,the rule of law and freedom.

The most widely accepted alter-native measure, to date, is theHuman Development Index (HDI)developed by economists MahbubUl Haq and Amartya Sen for theUN Development Programme in1990. The HDI was developed as acomposite indicator of human de-velopment incorporating educa-tion outcomes, health outcomesand income.

Broadly speaking, there is a pos-itive relationship between incomelevels and HDI scores. However,the relationship is not alwaysclear-cut. There are some coun-tries with low HDI scores despiterelatively high income levels (suchas Kuwait and Oman), and alsocountries with similar HDI scoresbut quite different income levels(like Indonesia and South Africa).

“Green GDP” has been pro-posed as a measure which wouldtake into account the depletion ofnatural resources and the cost ofenvironmental degradation. Theseenvironmental costs are mone-tised and deducted from tradition-al GDP. Economist Joseph Stiglitzhas been a key proponent of thisconcept. China’s first green GDPaccounting exercise revealed thatthe economic loss caused by envi-ronmental pollution alone (ignor-ing costs of natural resource deple-tion and ecological damage)amounted to 511.8 billion yuan or3 per cent of GDP in 2004.

The search for alternatives con-

tinues. The Commission on theMeasurement of Economic Per-formance and Social Progress, ledby three economists – ProfessorSen, Professor Stiglitz and Profes-sor Jean-Paul Fitoussi – identifiedeight dimensions of well-being asindicators of social progress, ofwhich material living standardswas only one.

Similarly, the Organisation forEconomic Cooperation and Devel-opment developed the Better LifeIndex in 2011. It incorporatedthree dimensions of material liv-ing conditions and eight dimen-sions of quality of life. And theUN Sustainable Development Solu-tions Network released the firstWorld Happiness Report in 2012,based on subjective measures ofwell-being from nationally con-ducted surveys.

So does all this make GDP irrel-evant? Not quite. Income is still avital and necessary aspect ofwell-being. And what is measura-ble is more manageable. But it iscertainly not all-sufficient.

So the current call to actionwould be to: first, improve uponthe methodologies of alternativemeasures; and second, consider avariety of measures which capturedifferent aspects of well-being,rather than focusing on a [email protected] writer is a Visiting AssociateProfessor in the Department ofEconomics, National University ofSingapore.

The return of Monica Lewinsky

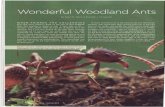

A paddy field in Ba Vi district, outside Hanoi, in February. South-east Asia is an area of extreme economic diversity; forexample, Singapore is a services-based economy while Thailand and Vietnam are big agricultural exporters. PHOTO: REUTERS

Singapore is among the top six economies globally in terms of income per capita,and is ranked 18th in the 2013 Human Development Report. PHOTO: BLOOMBERG

Report cardon Aseaneconomicintegration

ASK: NUS ECONOMISTS

GDP stillrelevant inassessingwell-being

T H U R S D A Y , M A Y 8 , 2 0 1 4 OOPPIINNIIOONN A27