One Tongue Many Voices Chap1

-

Upload

mhc032105636 -

Category

Documents

-

view

421 -

download

10

Transcript of One Tongue Many Voices Chap1

Contents

List of Figures xi

Acknowledgements xiii

List of Abbreviations and Special Symbols xiv

Preface xv

1 English – the Working Tongue of the Global Village 1English is spoken in circles 2The Inner Circle 3The Outer Circle 4The Expanding Circle 5Do we need a world language? 5Why English? 6One or two explanations 8

Part I History of an Island Language

2 The First 500 Years 13Roman Britain 14Ships are sighted with English in embryo on board 17Christianity in the Isles 19The Viking age 22What was Old English like? 27The Lord’s Prayer 27Beowulf 30Two translations into Modern English 32

3 1066 and All That 33Middle English 36An influx of French words 36Grammatical endings disappear 39Geoffrey Chaucer and William Caxton 40

4 Modern English in the Making 46The Three ‘Rs’ – Renaissance, Reformation, Restoration 47English and Latin 48

vii

The Elizabethan period 50Shakespeare’s language 54The King James Bible – a milestone in the history of English 58Restoration and reaction 60English gains a new domain – the language of science 63‘Dictionary Johnson’ 64The ‘End of History’? 65Codification of the standard language 67

Part II The Spread of English around the World 69

5 English Goes to the New World 71English takes root in America 72The Pilgrim Fathers 75The first Americanisms 76Linguistic variety and uniformity in the United States 78The American Revolution 82The frontier moves further west 85New Americans 89English goes to Canada 90Cartier and Canada 91Loyalists’ influence 93Canadian English 95

6 English Transplanted 98Australia: the First Fleet 99Kangaroo, koala, kookaburra become English 101Australian English 104New Zealand – Aotearoa 105New Zealand English 108English in Africa – the Inner Circle 110English comes to South Africa 112English in Africa – the Outer Circle 115English in South Asia 117‘The jewel in the crown’ 117English in Southeast Asia 119New Englishes 121

7 English Varieties in the British Isles 124RP (Received Pronunciation) 125Cockney 128Estuary English 130

viii Contents

The North 132The West Country 133Vernacular grammar 134English in Wales 135English in Scotland 136Scottish varieties 140English in Ireland 144

8 American and British English 150‘Divided by a common language’? 152Americanisms and Americanization 157Persistent transatlantic differences of vocabulary 159American and British pronunciation: comparing GA with RP 163American vs. British grammar 166AAVE – Black English – Ebonics 169

9 From Caribbean English to Creole 174Pidgins and creoles 176Jamaican creole 179Sranan 181The life cycle of a creole 183The Atlantic creoles and their characteristics 185Tok Pisin 187

Part III A Changing Language in Changing Times

10 The Standard Language Today 191Standard English – the written language 193Vocabulary – combining the North Sea and the Mediterranean 197A spectrum of usage – from speech to writing 199Is spoken English grammatical? 203

11 Linguistic Change in Progress: Back to the Inner Circle 206Grammaticalization 206Colloquialization 207Liberalization? 209Americanization 210Is English becoming a more democratic language? 211Is English becoming a non-sexist language? 215Electronic English 219

Contents ix

12 English into the Future 222One English or many Englishes? 222World English 225The globalization of English 227English as a lingua franca 232‘Reports of the death of the native speaker have been exaggerated’ 235

What is happening in the heartland of English? 237Changing American voices: Northern Cities Shift 239The English juggernaut? 241And where is it all going? 246

Notes: Comments and References 247

References 266

Index of People 274

Index of Topics 276

Pronunciation 286

x Contents

English, no longer an English language, now grows from many roots.Salman Rushdie,

The Times, 3 July 1982

Ahead of his time, the Canadian writer Marshall McLuhan predicted thatelectronically connected media would eventually transform the world into ahuge ‘global village’. English has become the working tongue of that village.

It is a new feature in the history of languages and language learning that thisdemand for English comes largely from the grass roots, not from society’s elite,as was the case with Latin forced down the throats of previous generations ofschool pupils, or as the English language itself was imposed in earlier times onspeakers of Celtic, Bantu or many other languages. The most remarkable thingabout English today is not that it is the mother tongue of over 320 million people,but that it is used as an additional language by so many more people all aroundthe globe. Non-native speakers in fact outnumber native speakers – probably aunique situation in language history. There are estimates suggesting that abouta quarter of the world’s population know, or think they know, some English.But, of course, sheer numbers mean little here – the expression ‘know English’has plenty of latitude.

According to Ethnologue, a database maintained by the Summer Institute ofLinguistics in Dallas, Texas, there are today about 6,800 distinct languages inthe world. Yet just five languages – Chinese, English, Spanish, Russian andHindi – are spoken by more than half of the world’s population. And Englishcannot claim the highest number of native speakers; Chinese has about threetimes as many. What gives English its special status is its unrivalled position asa means of international communication. Most other languages are primarilycommunicative channels within, rather than across, national borders. Today,English is big business and the most commonly taught foreign language all overthe world.

1English – the Working Tongue of the Global Village

1

So why this demand for English among language learners around theworld? The reason is not that the language is easy, beautiful or superior in lin-guistic qualities. Most people who want to learn it do so because they need it tofunction in the world at large. Young people, finding it both practical and cool, areattracted by things they can do with English, such as listening to music, watchingfilms and surfing the web. For scientists and scholars, English is a necessity forreaching out to colleagues around the globe, publishing results from theirresearch and taking part in international conferences. For tourists, English isthe most useful tool for getting around and communicating with people allover the world.

English is spoken in circles

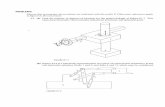

The Indian-American scholar Braj Kachru has taught us to think of English, asused around the world, in the form of three concentric circles (see Figure 1.1).The Inner Circle represents a handful of countries where most of the inhabitantsspeak English as a first language. The Outer Circle includes a larger number ofcountries where English is a second, often official or semi-official, language, butwhere most users of the language are not native speakers. Beyond the Inner andOuter Circles, English is learned and used as a foreign language in the hugeExpanding Circle, which in fact includes most countries in the world.

2 English – One Tongue, Many Voices

Outer Circle

Inner Circle

Expanding Circle

Figure 1.1 The three concentric circles of English worldwide

The Inner Circle

The Inner Circle includes, above all, three geographical blocs: the United States,Canada and the West Indies in the New World; Britain and Ireland in Europe;Australia, New Zealand and South Africa in the Southern Hemisphere. In theseeight regions there are over 320 million people speaking English as a first lan-guage, and two out of three of them live in North America.

In some countries there are different figures for population and speakers ofEnglish as a first language (see box below). For some 40 million Americans thefirst language is Spanish – in fact, Hispanics have now replaced AfricanAmericans as the largest minority group of the United States. Canada is offi-cially a bilingual country where almost a quarter of the population reportFrench to be their mother tongue. In addition, native Canadians speak variousindigenous languages. The Republic of Ireland has two official languages, IrishGaelic and English, but only a small proportion of the population use Gaelic. InBritain and Ireland, English is the first language of over 60 million inhabitants.What many people find surprising is that neither in the United States nor inBritain, the two countries that seem to have imposed their language on theworld, has English ever been formally declared the official language.

In the Southern Hemisphere, English is spoken by almost 20 million Australiansand New Zealanders. While this is a modest figure compared with the numberof native speakers in North America and Europe, English is an important meansof communication around the expansive Pacific basin. South Africa is a specialcase with eleven official languages, one of which is English. It stands astride theboundary between the Inner and Outer Circles. English is not its primary lan-guage: among the population, English has a first language share of less than10 per cent – in South Africa, English has always been a minority language, yetits population of native speakers is comparable in size to those of Ireland andNew Zealand. In South Africa today, English retains a dominant position: it isthe language most commonly used in Parliament and the main medium ofinstruction in higher education.

English – the Working Tongue of the Global Village 3

Countries in the Inner Circle

Countries English as a first language PopulationUnited States 215 million 278 millionUnited Kingdom 58 million 60 millionCanada 20 million 32 millionAustralia 15 million 19 millionCaribbean 6 million 6 millionIreland 4 million 4 millionNew Zealand 4 million 4 millionSouth Africa 4 million 44 million

Totals 326 million 447 million

People who happen to be born in the Inner Circle of course enjoy a privilegesince they learn, for free (more or less), to speak this global language with anative accent. Their language gives them a certain global reach and an advantagein many walks of life, whereas those who happen to be born into the Outer andExpanding Circles have to put years of time and effort into attaining some mas-tery of the language. For obvious reasons, in English-speaking communitiesthere is a widespread lack of enthusiasm for learning other languages. But life inthis ‘fast language lane’ of native English speakers comes at a price. HavingEnglish as your mother tongue means you lose out in the direct experience offeeling at home in other cultures and life-styles. You view the world throughEnglish-tinted glasses. The other side of this coin is that, among speakers of theworld’s other languages, there are fears that the pervasive influence of Englishwill undermine their own cultural and linguistic identities.

The Outer Circle

In countries outside the Inner Circle, English has different societal functions,and it is therefore practical to place these countries in two different circles: theOuter Circle and the Expanding Circle. Yet there are linguists who argue that,today, a distinction between English as a second and a foreign language is notrelevant. In their view, it doesn’t really matter whether you learn English in, say,Nigeria or Japan. Recently English linguistic influences have been penetratingfurther into countries like China, Mexico and Norway, for which it has alwaysbeen a foreign tongue.

In the Outer Circle we mostly find people who live in former British colonies,such as Kenya and Tanzania in Africa, and India, Pakistan, Malaysia andSingapore in Asia. In many of these countries, English is an official languageand widely used in administration, education and the media. India is a strikingexample of the spread and importance of English in the Outer Circle. In thiscountry with more than a billion inhabitants and 200 languages, English has heldits position and is widely used in government administration, the law courts,secondary and higher education, the armed forces, the media, commerce andtourism. Estimates suggest that some 4 per cent of the population – more than40 million people – now make regular use of English. Going further than this,David Crystal’s book English as a Global Language gives the figure of 200 millionfor the number of Indian second-language users of English. Whichever of thesefigures we accept – and such estimates are bound to be hazy – India is among theleading English-using nations in the world.

However, as we shall see, the question of whether a country belongs to onecircle or another – like the question of what makes a speaker a native speaker ofEnglish – is trickier than one may think.

4 English – One Tongue, Many Voices

The Expanding Circle

The Expanding Circle encompasses large parts of the world where English islearned as a foreign language because it is found useful, or indeed indispensable,for international contacts in such areas as industry, business, politics, diplomacy,education, research, technology, sports, entertainment and tourism. Today thereare hundreds of millions of people who, though not living in an English-speakingcountry, have acquired a good working knowledge of English. This circle nowseems to be ever-expanding, strengthening the claims of English as the inter-national language of today. Is this expansion of world English going to reachsaturation point? Arguably it is, and in the not too distant future, it will beappropriate to rename the ‘Expanding Circle’ the ‘Expanded Circle’.

Do we need a world language?

In the history of the world up to now, there has never been a situation whereone language could claim global currency. There have been languages, likeLatin during the Roman Empire, that gained widespread international currencythrough military might or economic influence. But this was not a worldwideconquest: even in Roman times there were barbarian hordes living beyond theempire, and there were vast tracts of the world that the Roman legions neverreached. So why should we now think in terms of a world language? Is thereany need for one?

The answer to such questions, above all in the globalized society we live intoday, must be ‘Yes’. To overcome the confusion of tongues, people have triedin the past to make up artificial international languages, such as Esperanto, Ido,Volapük, Novial, Interglossa, Interlingua. The most successful of these has beenEsperanto, yet, despite the high hopes of previous generations that Esperantowould take over the world, artificial languages have met with little success. It istrue that the grammar of artificial languages has been planned to be regular andeasy to learn and their vocabulary combines elements from different languages.Yet somehow, these advantages have not weighed against the built-in advan-tages of a natural language which already has a head start in the internationallanguage stakes. English already had this head start, and gradually extended itshegemony through the twentieth century.

As a bonus, a natural language also offers a cultural milieu and a rich canonof literature. In the case of English, this literary canon originates both in theInner and Outer Circles: embracing not only Jane Austen, Ernest Hemingway,Patrick White and William Butler Yeats, but also Arundhati Roy, Wole Soyinka,Ngugi Wa Thiong’o and Derek Walcott.

English – the Working Tongue of the Global Village 5

Why English?

English did not become a world language on its linguistic merits. The pronun-ciation of English words is irritatingly often at odds with their spelling, thevocabulary is enormous and the grammar less learner-friendly than is generallyassumed. There are people who think it is much to be regretted that some otherlanguage, like Italian or Spanish with their pure vowel sounds and regularspellings, did not achieve the status of lingua franca. David Abercrombie, awell-known Scots phonetician with a keen interest in English teaching, oncesuggested that spoken Scottish English, not English English, should be usedinternationally because of its superior clarity. In fact, foreigners often findScottish English with its clear r’s easier to pronounce and understand thanSouthern British English with its r’s either not pronounced (as in girl) orobscurely pronounced (as in right) – see p. 125, 142. Also, with few diphthongs,Scottish vowels are similar to those widely heard throughout the world, includingon the European Continent.

True, English grammar has few inflectional endings compared to languageslike German, Latin or Russian, but its syntax is no less complex than that ofother languages. A comprehensive grammar of English is definitely no shorterthan, say, a grammar of French or German, as has recently been demonstratedby Rodney Huddleston and Geoffrey K. Pullum’s Cambridge Grammar of theEnglish Language with more than 1,800 pages. So it is totally wrong to suppose,as some native speakers actually do, that English has no grammar. The grammarof English not only exists, but has been subjected to more detailed study thanthat of any other language.

As everybody knows, the English word stock is vast. Any major dictionary of theEnglish language has over a 100,000 headwords, and the most comprehensive ofthem all, the Oxford English Dictionary, defines a total of over 600,000 words.With its 20 volumes this lexical whopper occupies a great deal of shelf spacebut, fortunately, is now available in electronic form. The third edition nowin progress, and to be completed in another 20 or so years, will be ‘an OED somassive as perhaps only to be amenable to use on-line’. Yet, while all thesewords exist in the dictionary, no native English speaker knows them all. Theaverage native speaker probably uses no more words than a speaker of any othermajor language.

So what made English the world language? Behind its success story thereare two main factors: first, the expansion and influence of British colonialpower – by the late nineteenth century the British Empire covered a considerablepart of the earth’s land surface, and subjects of the British monarch totallednearly a fourth of the world’s population; second, the status of the United Statesof America as the leading economic, military and scientific power of the twentiethcentury.

6 English – One Tongue, Many Voices

And there are yet other contributing factors. One is the increasing need forinternational communication as a result of modern technology: such innova-tions as the telephone, radio, television, jetliner transport and computers eachintroduced a step-change in the potential for international communication.Air traffic controllers all over the world use English when talking to pilots,whether Russian or Danish or Chinese, and whether at Kennedy or Schiphol orNarita airport. And, of course, in information technology, American Englishis king.

Yet another factor: in countries or groups of countries where people have severalor many different first languages, English may be the preferred lingua francabecause it is felt to be neutral ground. In the global economy, many multi-nationals have adopted English as the workplace vernacular. Half of all Russianbusiness is said to be conducted in English. In the European Union, the practical‘working language’ in communication across language barriers is usuallyEnglish, often reluctantly adopted as the only language that is sufficientlywidely used. Across the Union (excluding the British Isles), nine out of tenstudents choose to study English as a foreign language. English is said to permeateEU institutional activities and many areas of cultural and economic life moreand more thoroughly. Today, it is hardly possible to pursue an internationalcareer without English. As a window on the world, English is looked upon asthe best means to achieving economic, social and political success.

The aim of this book is to explore this astonishing global phenomenon. Thehistory of English as a separate language started about CE 500, when its ancestorwas a collection of dialects spoken by marauding Germanic tribes who settledin the part of the British Isles nearest the European continent. In those distantdays, this proto-English was spoken by less than half a million illiterate people.Compared with the prestigious Latin language which had dominated the westernRoman Empire up to that time, it was a totally insignificant tongue. In the1,500 years since then, the English language has come heavily under the influenceof other languages, especially Old Norse, French, Latin and Greek. Eight hundredyears ago it was a humble medley of native dialects in a country where therulers spoke French. Yet it somehow survived as a basically Germanic language,and has now come to be known to something like 11⁄2 billion people.

This fantastic story needs to be told, and so, in Chapters 2–6, we look backand trace the history of English as it developed in the British Isles and later interritories conquered and settled through the growing British maritime andcommercial power. But when we reach the last two centuries, the story ofEnglish becomes international and worldwide. Around 1880 the United Statesbecame the leading English-speaking nation, in both population and wealth.Chapters 7–8 tell the story of how the English language has evolved today inthe British Isles and the United States, building on the historical foundationalready described. Chapters 9–10 deal with pidgins, creoles and standard language.

English – the Working Tongue of the Global Village 7

Chapter 11 describes some of the on-going changes in the current English lan-guage. Finally, Chapter 12 looks to the future: all languages being works inprogress, what will happen to English? Will it split into mutually incompre-hensible languages, as Latin did? Or will it remain a single language, in spite ofall the variety of its manifestations around the world? Will it remain the leadinglanguage of international communication? Or will it be overtaken by anotherlanguage? We don’t know the answers to these questions, yet they are worthasking and debating in an informed way.

One or two explanations

First, why are three chapters (2–4) of this book devoted to what happened inremote periods of history? The answer is simple. What the English language looksand sounds like today is fundamentally due to distant events: the Germanicmigrations and invasions, the Norman Conquest, the introduction of printing,the Renaissance. Recent centuries have brought their own story of the growing

8 English – One Tongue, Many Voices

2000: 1–1.5 billion

1900: 116–123 million

1800: 20–40 million

1700: 8.5 million

1600: 6 million

1500: 4 million

Figure 1.2 The mushroom of English

Over the centuries, the number of users of the English language can be seen as forminga mushroom with a slim base and a huge cap. These statistics, necessarily approximateof course, derive from Otto Jespersen’s Growth and Structure of the English Language(pp. 233–4) and David Crystal’s English as a Global Language (pp. 62–5). Yet what can bestated with some certainty is that, in the long history of the English language, themushrooming effect is of quite recent date. In the 1936 edition of The AmericanLanguage, H. L. Mencken gave 174 million as the estimated number of native speakers.As for speakers outside what we have called the Inner Circle, he wrote: ‘it is probable thatEnglish is now spoken as a second language by at least 20,000,000 persons throughoutthe world – very often, to be sure, badly, but neverthess understandably’ (p. 592). Howthings have changed!

international dispersion of English, but this story builds crucially on moreancient foundations.

Second, we try hard to avoid confusion between describing linguistic realities(which we aim to do) and making value judgements (which we do not). AsDavid Crystal remarked in the preface to his book English as a Global Language:‘It is difficult to write a book on this topic without it being interpreted as apolitical statement.’ It is easy to fall into the trap of considering English asuccessful language because of its inherent qualities as Melvyn Bragg arguablydoes in his book The Adventure of English, rhapsodizing over the Elizabethan ageof English: ‘English was now poised to grow into a richness, a subtlety andcomplexity which would enable it to become a world language.’

There is no room in this story for triumphalism. On the other hand, it is easyto fall into the opposite trap of seeing the spread of English on a global scale asa linguistic form of imperialism, as has been argued by Robert Phillipson in hisbook Linguistic Imperialism. We believe it is better to see the rise of English inmore objective terms. It has won out in the linguistic ecology of the twentiethcentury rather as dinosaurs won out in the battle for survival above otherspecies in the Jurassic period, or as homo sapiens is dominating other species inthe survival battle of the present age. But there is a crucial difference: theEnglish language has won out, at least for the present, because of the political,economic and military success, at a crucial period, of the people who were itsspeakers, not because of the features of the language itself. This is an amazingstory to tell, but if we give any impression of glorifying English or the English,this is far from our intention.

The avoidance of value judgements is important, too, in discussing the differentkinds of English – the many varieties of the language, as they are called. We haveinherited a tradition of such judgements, for example, in the assumptions thatsome kinds of grammar are ‘correct’ and others ‘incorrect’; that standard lan-guage is somehow superior to non-standard dialects; that English as a mothertongue is somehow superior to the English of non-native speakers. It would befoolish to lay much store by such traditional attitudes. It is worthwhile remindingourselves that non-natives speakers of English in the world now outnumbernative speakers by at least three to one. Further, it is quite possible – and isseriously argued today – that the future of English will be more determined by themajority of its users – those in the Outer Circle and the Expanding Circle – thanby the Inner Circle, the traditional heartland of English. We return to thisdiscussion in our last chapter.

English – the Working Tongue of the Global Village 9

Abercrombie, David 6, 126Adams, John 71, 82–3Alfred, King of Wessex 23–4, 27Armstrong, Neil 217Ash, Sharon 239Athelstan, King 23Augustine 19

Bacon, Francis 49Banks, Joseph 98–9Beattie, James 192Beckett, Samuel 147Bede 20Bickerton, Derek 184Bismarck, Otto von 71Boberg, Charles 239Bonnie Prince Charlie 140Boswell, James 64–5Bradford, William 75, 77Bragg, Melvyn 9, 126Brathwaite, Edward 178Bruce, Robert 138Bryson, Bill 76, 152Burchfield, R. W. 39–40, 46, 124, 223Burns, Robert 141–3, 193Bush, George H. W. 210Bush, George W. 166

Cabot, John 90–1Caesar, Julius 15Canute, King 24Cartier, Jacques 91Caxton, William 43–5, 126, 220Chambers, J. K. 95, 97Charles I 48, 60Charles II 48Chaucer, Geoffrey 40–3, 191–2Chesterfield, Lord 192Chew, Phyllis Ghim-Lian 244Churchill, Winston 58, 62Claudius, Emperor 16Clinton, Bill 166Coghill, Nevill 42, 192Columbus, Christopher 90, 172, 174

Constantine the Great 19Cook, James 98, 106Cooper, James Fenimore 83Cranmer, Thomas 48Cromwell, Oliver 48Crystal, David 4, 8–9, 117, 123, 219,

227–8, 236, 242, 246

Daniel, Samuel 98Defoe, Daniel 13Desani, G. V. 119Dickens, Charles 193Doolittle, Eliza 129Dryden, John 62–3, 191–2

Edward I 135Edward III 41Edward the Confessor 34Edward, Prince of Wales 135Eliot, T. S. 222Elizabeth I 50, 72Evelyn, John 63

Fawkes, Guy 74Flack, David 229Fowler, H. W. 62Franklin, Benjamin 82

Gandhi, Mahatma 112, 118Gilbert, Sir Humphrey 91Graddol, David 224, 228, 242, 246Gregory, Pope 19Guthrum 23Görlach, Manfred 245

Hadrian, Emperor 16Halliday, M. A. K. 126Harold, King 33Heaney, Seamus 31, 147Hemingway, Ernest 86Henry V 35Henry VIII 47, 58Hibbert, Frederick ‘Toots’ 180Higden, Ranulf 33, 36

274

Index of People

(Note: This index covers the main text, but not the Notes section.)

Index of People 275

Higgins, Henry 129, 223Huddleston, Rodney 6

James VI and I 58, 72–3, 139Jefferson, Thomas 82–3Jespersen, Otto 8, 24John, King 35Johnson, Lyndon 166Johnson, Samuel 64–5, 154, 192Joyce, James 147

Kachru, Braj 2, 226Kennedy, John F. 212Kipling, Rudyard 160Koyoi, Mikie 236

Labov, William 164, 239–40Lang, J. D. 102Lincoln, Abraham 77Locke, John 61

Macaulay, Thomas 118MacDiarmid, Hugh 141Mandela, Nelson 113McArthur, Tom 67, 223–5, 229McCoy, Joseph 86McLuhan, Marshall 1Mencken, H. L. 8, 79, 157Metcalf, Allan 166Millward, Celia M. 124Milton, John 61More, Sir Thomas 49Mulcaster, Richard 56

Naipaul, V. S. 178Nelson, Lord Horatio 83, 113Newton, Isaac 61, 63

Ogden, C. K. 235

Paikeday, Thomas 235Paterson, ‘Banjo’ 102Patrick, Peter L. 180Pennycook, Alastair 243Phillip, Arthur 99Phillipson, Robert 9Pickering, John 158Platter, Thomas 52Pope, Alexander 63, 191Porter, John 31Potter, Simeon 38

Pullum, Geoffrey K. 6

Quirk, Randolph 191, 235

Ralegh (or Raleigh), Sir Walter 72Reagan, Ronald 82Richards, I. A. 235Rowling, J. K. 161Roy, Arundhati 119Rushdie, Salman 1, 118

Safire, William 150Saussure, Ferdinand de 206Scott, Sir Walter 39Sebba, Mark 238–9Seth, Vikram 119Shakespeare, William 50–8, 210Shaw, George Bernard 128, 147, 223Sinclair, John 126Singer, Isaac Bashevis 90Solander, Daniel 99Spenser, Edmund 46Stein, Gabriele 191Steinbeck, John 71Stenström, Anna-Brita 237Sweet, Henry 223Swift, Jonathan 64–5, 147Synge, John Millington 147

Thumboo, Edwin 243Thiong’o, Ngugi Wa 242Tottie, Gunnel 166Trevisa, John of 33, 36–7Trudgill, Peter 132Twain, Mark 86, 129, 235Tyndale, William 58

Vespucci, Amerigo 85

Walcott, Derek 174, 178Waller, Edmund 62, 191Wanamaker, Sam 54Washington, George 82, 166Webster, Noah 71, 154, 223Wekker, Herman 181Wells, J. C. 104, 130, 166, 238Wilde, Oscar 35, 147William the Conqueror 33–4Witherspoon, John 158

Yeats, William Butler 147

AAVE, see African American VernacularEnglish

abbreviations in e-communication 220Aboriginal languages 94, 102Aboriginal loanwords 101–2Aborigines, the 98, 101–2academic writing 200Acadia 92accent as a class marker 124–8accent, prestigious 125–8accommodation 227acrolect 116, 176–7, 226acronyms 209, 220–1advertising 229, 244African American Vernacular English

(AAVE) 169–72, 176–7, 186, 239African Americans 170, 172African English 115–17African languages 114African National Congress 113Afrikaans 113, 243Afrikaner 112–15Afro-Caribbean heritage language 239agreement in grammar 167ain’t 134air traffic 230airlines 229aitch-dropping 129Aku 185Algonquian 76–8alphabetisms 209, 220American accents 81–2, 163–6, 239–41American Language, The 157American Revolution, the 71, 82, 88, 93American Spelling Book, The 154Americanisms 76, 157–9Americanization 157–9, 206, 210–11Angles 17Anglo-Irish 148Anglo-Norman French 35Anglo-Saxon 18, 27–32, 59Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, The 22Anglo-Saxon kingdoms 20, 23–4, 29

Aotearoa (New Zealand) 105–10apartheid 113Arabic 66, 87, 225, 228, 246artificial languages 5, 235Athabaskan 77Atlantic creoles 185–6Auld Alliance, the 138Auld Lang Syne 143Aussie 100Australia 3, 98–105Australia Day 99Australian Aborigines 98, 101–2Australian English 100, 104–5,

108–10, 114Authorized Version of the Bible, the

58–60

Bahamas, the 174Bajan 185Bangladesh 117Bannockburn, battle of 138Bantu family of languages 114Barbados 177, 185Basic English 235basilect 116, 156, 176–8, 184, 226Bayeux tapestry, the 34BBC English 57, 124–6BBC television 228be going to 207be supposed to 207Belize 174Benedictine Revival, the 21Bengali 117Beowulf 30–2, 199Bible translations 58–60bilingualism 3, 40–1, 94, 105, 135, 148,

172, 225, 228, 231biographies 200Birmingham 132Black 172Black English 169–72blogs 224Bonfire Night 74

276

Index of Topics

(Note: This index covers the main text, but not the notes section.)

Index of Topics 277

Book of Common Prayer, the 48, 55Boston Brahmin accent 81brahmin 119brand names 229Breton 14Brit 15Britain (Great) 3, 15–19, 23, 64,

124–44Britannia 15–16British and American English 150–69British Council, the 228British creole 239British East India Company, the 118British Empire, the 223British Isles, the 7, 14–16, 19, 45,

124–49British Raj, the 118Briton 16, 110, 152, 156Broad Scots 140Brussels 232–3Buffalo 240Burns Night 143business and commerce 229

Cajuns 92California 85, 88California Gold Rush, the 88Cambridge (England) 125, 192Cameroon 185Canada 3, 77, 90–7, 244Canadian English 90–7Canadian French 94Canadian raising 96Canterbury 19Canterbury Tales, the 41–3Cantonese 121Cape of Good Hope, the 112Caribbean creoles 185–6Caribbean English 174–8Caucasian 172cell phone 220Celtic 14, 18, 147Celtic languages 14–15, 135, 138, 145Celtic substratum 135Celts 14centrifugal force 225centripetal force 225chain shift 109, 240–1chair 217chairman 217chairperson 217chairwoman 217

Chancery English 43chat groups 224Chicago 240Chicana, Chicano 172children’s English education 231China 121, 246Chinese 223–4, 228, 230, 246Christianity in Scotland 137Christianity in the Isles 19–22Church of England, the 58, 75class accent 125Cleveland 240CNN International 227cockney 100, 104, 128–30, 238code-switching 122–3codification 67, 193coinages of new words 220collective nouns 167colloquial style 134, 196colloquialization 206–9colonial period of immigration, the 79common gender nouns 216common language, a 152, 154, 176, 184,

224, 228Commonwealth, the 48communication 220, 230concord in grammar 167conference talk 227Connecticut 75consumer culture 229contact languages 176content words 197continuum of accents 127continuum of language variation 172,

176, 199–200contractions 208, 210core vocabulary 67, 199Cornish 14, 18Cornwall 18correctness 209cowboy 86creole languages 111, 174, 176–88creolization 183–85Culloden, battle of 140Cumbria 18Cymraeg 15, 135Czech Republic, the 229

Danelaw, the 23–4, 26Danish 13–14, 19, 21, 23–4, 141, 197Declaration of Independence, the 75,

82–3, 154

278 Index of Topics

decorative use 229decreolization 183–5democratic language 211–15Denmark 24, 30, 58, 231description 67Detroit 240developing countries 232Devon 133Dictionary of the English Language, A

64, 154diglossia 225disintegration 223distance education 231divergence 224diversification 222divided usage 218do-construction, the 54, 211Dominion of Canada, the 94do-support 54, 211double negation 134, 171doublets 37–9Down Under 100Dream of the Rood, the 20, 136dub poetry 180dude 214Dutch 14, 21, 80, 83, 98, 105, 111–13,

176, 182, 185, 231Dutch East India Company 112Dutch Guiana 181

Early Modern English 46–67East Africa 232East African English 116East Anglia 23East Midland dialect, the 43eastern seaboard (of North America),

the 80Ebonics 169–72e-business 228Edinburgh 106, 138–9, 194education 230–1Egypt 225eh? 97e-language 219–21electronic English 219–21electronic revolution, the 228Elizabethan English 54–8Elizabethan period, the 50–4Elizabethan theatre, an 53e-mail 221, 224, 228emigrant 89

emoticons in e-communication 221emotive expression 202, 220English academy, an 64English as a foreign language 1–2,

4–5, 7, 35, 79, 90, 120, 124, 126, 132,152, 188, 235

English as a lingua franca 7, 232–5English as working language 7, 141,

229–30English Civil War, the 48English English 6, 125–35, 141, 237–9English in Africa – the Inner Circle

110–15English in Africa – the Outer Circle

115–17English in Canada 90–7English in China 121English in Ireland 144–9English in Scotland 136–44English in South Asia 117–19English in Southeast Asia 119–21English in Wales 135–6English language learning 231English Separatist Church, the 75English teaching 6, 67, 127, 170, 193,

231, 233–4English varieties in the British Isles

124–49English-based creole 174, 184Englog 244–5e-revolution, the 219Erie Canal, the 89Eskimo 94Esperanto 5, 235Estuary English 128, 130–2, 164,

238–9, 241Euro-English 232European Union, the 7, 232Eurospeak 232Expanding Circle, the 2, 5, 231, 236expeditions to the New World 72–5

face-to-face communication 200, 224false Latinisms 50family names 212fauna 78, 102, 105, 107female suffixes 216First Fleet, the 99First Folio, The 51–2first names 212First Nation in Canada 94

first-name terms, on 212Flemish 14flora 78, 102, 105, 107foreigner talk 227forenames 212formal style 196forms of address 211–12Forty-Five, the (the 1745 Rebellion) 140Founding Fathers, the 72Fourth of July, the 77fragmentation of English 223Francophonie, la 94Franglais 244–5French 3, 6–7, 25, 33–43, 46–8, 50,

55, 61, 63–5, 72, 83, 91–5, 136, 138,145, 175, 197–9, 227, 230, 232–3, 244–5

French in Canada 91–5French words 36–9, 138, 165, 197–9French-English doublets 37–9French-speaking Canada 91–5, 244Frisian 14, 19frontier, the 85function words 197future of English, the 222–46

GA, see General AmericanGaelic languages 14–15, 106, 138,

140–1, 145, 147–8Gaeltacht, the 145, 147Gambia 116, 185gender bias 216–18gender-neutral pronoun 215–16gender-neutral terms 216–18General American 57, 81–2, 96, 122,

125, 239–40General RP 127generic use of he 218genitive, the 209Geordie 133, 142German 14, 19, 225, 245German immigration to America

80, 89Germanic invasion, the 17–19Germanic languages 14, 19, 24, 183,

198, 231Germanic words 38, 197–9Gikuyu 243given names 212global English 240–5globalization 241

globalization of English 227, 231–2Globe (Theatre), The 52–4glottal stop 129–30, 133, 238golden triangle, the 192gonna 207Gothic 14gotta 207grammar: differences between American

and British English 166–9grammar-checking software 208grammaticalization 206–7Great Britain 16Great Lakes, the 241Great Vowel Shift, the 61, 109,

141, 240Greek loanwords 48–9, 56, 66, 155,

196–9, 201Greek prefixes and suffixes 208Greek word elements 36, 66Guid Scots Tongue, the 140Gullah 185Gunpowder Plot, the 74guy 74Guyana 174–6guys 74, 158, 169, 202, 214–15

Hadrian’s Wall 16hafta 207haggis 143Hamlet 57harass, harassment 40Hausa 232have got to 207have to 207h-dropping, see aitch-droppingHebrides, the 140Hiberno-English 148Higden’s Polychronicon 33, 36High Rising Terminal 109, 149Highlands, the 138, 140Hindi 117Hispanic 172Hispanics 3, 87, 172home language 114, 170Hong Kong 121honorific vocatives 211–12Hudson’s Bay Company 91Hundred Years War, the 35

Icelandic 14, 24identity 226

Index of Topics 279

immigrant 89immigration to America 79–81imperial expansion 227Independence Day 77, 83India 4, 117–18, 121–2, 231Indians 77, 94, 112, 172individualism in terms of address 215Indo-European languages 14, 18, 117industrial revolution, the 227informal style 196informative varieties 200Inland North (of the US), the 239Inner Circle, the 2–4, 175, 193, 214, 226,

235–6, 241intelligibility 226, 241interactive varieties 200, 202,

204, 219interactiveness 202, 220interlanguage 234international aviation code, the 234International Civil Aviation

Authority 230international standard English 156international trade 229Internet, the 219, 224, 228, 230interpreting 233interviews 200Inuit, Inuk, Inuktitut 94involved varieties 200Iona 19–20, 137Ireland 3, 15–16, 19, 23, 80, 89, 128,

137, 144–9, 169Irish Americans 146Irish emigration to America 89, 146Irish English 128, 145, 147–9Irish famine 146Irish Gaelic 3, 14–15, 145–8Iroquoian 77Italian 6, 15, 17, 41, 46–7, 198Italian immigrants in the US 89Ivanhoe 39

Jamaica 175–81Jamaican Creole 174, 179–81, 183–5,

223, 238–9Jamestown 73, 76Japanese 66, 204, 211, 236, 242, 245Japlish 244–5Jewish immigrants in the US 90juggernaut 119jungle 119Jutes 17

Kamtok 185Kent 19Kenya 4, 116, 121King James Bible, the 58–60Kiwi 107Korean 211Krio 185Kru English 185

Lallans 140–1Lancashire 132language complex, the 224language death 242Latin 5, 14, 49, 56, 61, 63, 65–6, 72, 138,

198, 222–4, 232, 238Latin loanwords 20–2, 48–50, 197–8Latin word elements 66, 198, 208Latina, Latino 172Latinisms 48–50Law French 38learned vocabulary 199Leeds 132–3left-dislocation 204lexical density 203, 208lexifier language 183liberalization 209–10Liberia 185Limericks 146Limey 15Lindisfarne Gospels, the 20lingua franca 6–7, 114, 120, 122–3,

176, 181, 184–5, 229–30, 232–6, 238, 242

linguistic change 206–21linguistic diversity 233linguistic imperialism 9, 243–4Linguistic Society of America 170literary Ireland 147literary Scots 141literate culture 193Liverpool 132–3, 142loanwords from languages beyond

Europe 66loanwords from Latin and Greek 48–50,

56, 66, 155, 196–9, 201loanwords from Native American

languages 78London English 43, 239London Jamaican 238–9Lord’s Prayer, the 27–8Louisiana 92Louisiana Purchase, the 85

280 Index of Topics

Index of Topics 281

Lowlands of Scotland, the 136, 138, 140, 146

Loyalists, the 93

Ma’am 211–12machine translation 242Madam 211–12Malay 120, 245Malaysia 4, 119–20, 231Malaysian English 122–3Malenglish 245man 214Man, Isle of 18Manchester 132–3Mandarin Chinese 120–1, 223–4Manglish 244–5Manx 14, 18Maori 105–7Massachusetts 75may 206–7Mayflower Compact, the 75Mayflower, the 75–6media, the 229Mercia 23mesolect 116, 176–7, 180–1, 184, 224, 235metaphorical use of existing words in

e-communication 220Michigan 240–1Mid-Atlantic 233Middle English 36–45, 58–61middle names 212Midland American accent 82, 239Midland, the (US) 239Midlands, the (UK) 132Minnesota 241minority populations in the US 172Missouri 241mixed languages 175–6, 183, 232mobile phone 220modal auxiliary verbs 206–8motherese 227movies 230multidialectal 225multilingualism 228, 233multi-modal communication 224mushroom of English, the 8Muskogean 77must 207mystery and adventure fiction 200

national expansion period ofimmigration, the 79

native (L1) speakers 3, 6, 8–9, 61, 81, 95,114, 116, 118, 146, 150, 152, 176, 183,206, 218, 221, 225, 227–8, 230, 232,234, 236–7, 243, 246

Native American languages 77–8, 86Native Americans 77–8, 83, 86, 172Native people in Canada 94Near-RP 127need to 207Negro 172Net, the 219Netherlands, the 231Netspeak 219–21Network English 82new compounds in

e-communication 220New England 75, 77, 83New Englishes 121–3, 191, 205,

223, 236–7New France 91–2New South Wales 99New York City pronunciation 164New Zealand 3, 105–10New Zealand English 108–10Newcastle 132, 142Newfoundland 91news broadcasts 200newspaper editorials 200newspaper reporting 200nicknames 212, 214no distance in forms of address 213–15non-native (L2) speakers 1, 9, 185, 212,

225, 227, 234, 236, 246non-rhotic accent 81, 164non-sexist language 215–18Norman Conquest, the 33–6Norman French 35, 65, 138Normandy 26, 35Normans, the 34–5normative models 226Norn 138Norse 7, 22, 24–5, 34, 38, 65, 145North Central (US) 82, 239Northeastern American accent 81Northern accent (UK) 132–3Northern American English 95Northern Cities Shift 239–41Northern Ireland 147–8Northern Irish plateau 149Northumbria 19–20, 23, 137Northumbrian 136, 141Norway 4, 23

282 Index of Topics

Norwegian 14, 24Nuclear English 235

official documents 200official languages in South Africa

113–14official or unofficial recognition of

English 229Old English 18, 21–2, 24–5, 27–32, 34,

36, 39–40, 43, 50, 58–9, 61, 135–6, 138,141, 183, 196, 198–9

Old English inflections 29Old Norse 7, 22, 24–5, 34, 38, 65, 145Old Saxons 18on-line activity 203on-line processing 203, 220Ontario 93oral culture 193Outer Circle, the 2, 4, 9, 115, 121, 123,

226, 231, 236overseas experience (OE) 108Oxbridge accent 125Oxford 125, 192Oxford English Dictionary (OED) 6,

153, 223Oz 100

Pakistan 4, 117Papua New Guinea Pidgin 187–8paralinguistic dimensions in

e-communication 221Parliament of Ireland, the 148passive constructions 205, 208patois 179Pennsylvania Dutch 80personal letters 200personal names 212Philippines, the 120phrasal acronyms in e-communication

221pidgin languages 111–12, 176, 183–5,

187–8, 232Pilgrim Fathers, the 75Pilipino 120place-names 17, 24, 102, 106–7, 136pluralization 224Plymouth colony, the 75Polish immigrants in the US 90political standing of English 229polyglossia 225Pom, Pommy 15pop music 230

popular media 229post-creole continuum, the 183–5prefixes in e-communication 220prepared speech 200prescription 62, 67prescriptivism 208–9present progressive 208prestige accent 125printing age, the 43–5professional letters 200pronunciation in Britain 124–34pronunciation in the US 81–2, 163–6,

239–41pronunciation: differences between

American and British English163–6

proper names 212Puritans 48, 58, 73, 75putonghua 121, 224Pygmalion 129pyramid of standardization, the 127–8,

156, 226

Quakers, the 55, 80Quebec 93, 244

rastafarian language 178r-dropping 81, 166Received Pronunciation (RP) 57, 124–8,

164, 177, 238reference accent 82, 125, 238Refined RP 127Reformation, the 47–8reggae music 180regional accent 81, 126–8, 132regional variation 128region-neutral accent 127relative clauses 55, 208, 210Renaissance, the 47Republic of Ireland, the 15Restoration, the 47, 60retroflex r 57, 133, 144, 163r-ful accent 166Rhode Island 75rhotic accents 164, 166rhyming slang 129–30right-dislocation 205rising interrogative intonation 178river-names 18r-less accent 166Roanoke Island 72Roman Britain 14–19

Roman Empire, the 222, 232Romance languages 13–15, 36–9, 45,

176, 197–9, 201, 222, 224Romance words 36–9, 45, 197–9, 201Royal Society, the 63RP, see Received Pronunciationrunes 28–9, 136Russian immigrants in the US 90Ruthwell Cross, the 20, 136

Sabir 176Saint Patrick’s Day 144Saxons 17scale of accents, a 127scale of language variation, a 199Scandinavian attacks in Scotland 137Scandinavian conquest 19, 22–6Scandinavian loanwords 24–5Scandinavian settlement-names 26science 230science fiction 200scientific vocabulary 199Scotch 140Scotland 15–16, 19–20, 23–5, 58, 65, 72,

89, 128, 133, 136–44, 193Scots 140Scots language, the 137, 140–2Scots-Irish immigration to America 80Scottish (Standard) English 142Scottish 140Scottish Gaelic 14–15, 140Scottish Parliament, the 139, 141Scottish pronunciation 142Scottish Renaissance, the 141Scottish varieties 140–4Scouse 142Scouser 133Seaspeak 230second-person address 211semi-modals 207–8, 210Separatists, the 75Sepoy Mutiny, the 118sexual bias in the language

215–18Shakespeare’s language 54–8shall 206–7shared context 201Sierra Leone 185Singapore 4, 119–20, 244Singaporean English 122–3single world language, a 228Singlish 120, 122

Sir 211–12Six Counties, the 147slave trade, the 76, 183smileys in e-communication

219, 221social variation 128Somerset 73, 133–4South Africa 3, 111–15, 119, 243South African English 109, 112–15South African Indian English 112South Asian English 117, 226Southern accent 81–2, 171Southern American accent 81, 171Southern drawl 81Southern Hemisphere Chain

Shift 109Southland burr, the 109Southron 139Spanglish 244–5Spanish 1, 3, 6, 14, 86–9, 172, 174, 176,

197–8, 211, 227–8, 233, 245–6specification, lack of 202spectrum of usage 199–203spelling pronunciations 193spelling, standard 60–1spelling: differences between American

and British English 154–5split infinitive, the 62spoken and written English 199–203spoken language 34, 37, 56, 60–1, 122,

126, 132, 168, 192–3, 200–5, 207, 209,221, 223, 231, 237–8, 241

spontaneous speech 200Sranan 181–2, 184St Louis 241standard British pronunciation 127standard English 43, 46, 55, 116, 120,

123, 134, 141–2, 156, 168–73, 176–7,179–80, 183–6, 191–7, 199, 204–6, 211,218, 223, 225–7, 234–5

standardization of English 43street signs 229stress-timed pronunciation 116,

177–8, 236subjunctive, the 168, 210substrate languages 183substratum 135, 148, 183subtitles 231suffixes in e-communication 220Suriname 181–3surnames 212Swahili 66, 232

Index of Topics 283

Sweden 231Swedish 14, 19, 21, 24, 137, 141,

231, 233Switzerland 225syllable-timed pronunciation 116,

177–8, 236

tag questions 136, 204, 237Tagalog 120–1, 245Tamil 120Tangier Island 73Tanzania 4, 116tapped r 96, 133, 144, 163teaching of English 6, 67, 127, 170, 193,

231, 233–4technical terms 199technological revolution, the 227technology 5, 7, 85, 114, 161, 230–1,

242, 245teenagers, language of 237telecommunications 229telephone conversation 200text messaging in e-communication

220–1textspeak in e-communication 221Thames estuary, the 130Thanksgiving Day 77thee, personal pronoun 55, 133thirteen original states (of the US), the

73, 79–80, 83, 88–9, 98thou, personal pronoun 55, 133, 168, 211three concentric circles diagram 2Tobago 185Tok Pisin 187–8, 223, 232Toronto 96translation 23, 47, 58–9, 233, 242transnational corporations (TNCs) 229travel 230–1trilled r 143, 163Trinbagonian 185Trinidad 185TV series 230Tyneside 133

Ullans 147Ulster 147Ulster Scots 147, 223unisex names 213United Kingdom, the 3, 15, 139, 146–7United States history, some

milestones 88

United States, the 3, 6–7, 38, 71–2,75–90, 152–73, 239–41

Urdu 117USA, the 85

variety in usage 195–6verb contractions 208, 210vernacular English 122–3, 134–5,

156, 225Viking age, the 22–6Vikings in Ireland 145Vikings in Scotland 137Virginia 73, 76vocabulary: differences between

American and British English152–3, 159–63

vocatives 202, 211–14voiced tap 96, 164voiceless l in Wales 136Vulgar Latin 35, 223–24

Wales 15–16, 18–19, 128, 133, 135–6,147, 185

Waltzing Matilda 102–3wanna 207want to 207War of Independence, the 88Welsh 14–15, 18–19, 100, 135–6,

138, 233Welsh English 128, 136, 226Welsh place-names 136Wessex 23–4, 27West Africa 232West African English 116, 178West African languages 170West African Pidgin English (WAPE)

185, 232West Country, the (UK) 124, 128, 132–4,

144, 149, 164West Indies, the 3, 174, 185Western Isles, the 140word-formation 66word-order 36, 38, 62, 136, 178World English 5, 143, 152, 156, 225–6,

235, 242World Spoken Standard English

(WSSE) 227World Standard English (WSE) 156,

194–5, 223, 225–6World Wide Web, the 219written and spoken English 199–203

284 Index of Topics

Index of Topics 285

written language 34, 46, 48, 60–2, 126, 156, 167, 193, 199–203, 207–10,219, 221

Yankee 83Yiddish 90yod-dropping 164

York 19, 36Yorkshire 112, 132–3you all, y’all 168–9, 186you guys 74, 169, 214yous, youse 169, 186

Zulu 112, 243