ONE HUNDRED TWENTY-FIFTH SEASON Chicago … · technics of Berio’s Sequenza II, the landmark harp...

Transcript of ONE HUNDRED TWENTY-FIFTH SEASON Chicago … · technics of Berio’s Sequenza II, the landmark harp...

PROGRAM

ONE HUNDRED TWENTY-FIFTH SEASON

Chicago Symphony OrchestraRiccardo Muti Zell Music Director Pierre Boulez Helen Regenstein Conductor EmeritusYo-Yo Ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant

CSO Tuesday series concerts are sponsored by United Airlines.

This work is part of the CSO Premiere Retrospective, which is generously sponsored by the Sargent Family Foundation.

This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts.

Global Sponsor of the CSO

Tuesday, September 29, 2015, at 7:30

Riccardo Muti ConductorXavier de Maistre Harp

ChabrierEspaña

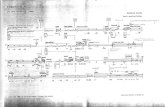

GinasteraHarp Concerto, Op. 25Allegro giustoMolto moderatoLiberamente capriccioso—Vivace

XAVIER DE MAISTRE

INTERMISSION

CharpentierImpressions of Italy SerenadeAt the FountainOn MulebackOn the SummitsNapoli

RavelBoléro

2

COMMENTS by Phillip Huscher

Emmanuel ChabrierBorn January 18, 1841, Ambert, France.Died September 13, 1894, Paris, France.

España

España is the sole survivor of a once-prestigious career. The only work by Emmanuel Chabrier that is still performed with any regularity, it began as a simple souvenir of six months in Spain. Chabrier and his wife spent the latter half of

1882 traveling the country, stopping in Toledo, Seville, Granada, Malaga, Valencia, and Barcelona. Chabrier’s score is one of the high points in the late-nineteenth century’s fascination with the Iberian peninsula that also inspired Édouard Manet’s paintings of the 1860s, Lalo’s Symphonie espagnole in 1873, and Bizet’s Carmen the following year (joined in the next century by Debussy’s Ibéria and Ravel’s Rapsodie espagnole).

Chabrier’s close friendship with Manet—his neighbor from 1879 to 1883—may have first given him the idea to compose a Spanish piece. Chabrier had once thought of being a painter himself, and he closely followed the work of the groundbreaking French artists during his lifetime, regularly noting how closely their ideas paralleled his own. Chabrier posed for Manet on three occasions, the last time in 1881, only months before the Chabriers set off for Spain. When Manet died in 1883, Chabrier bought

several of his canvases, including his last major work, the celebrated Bar aux Folies-Bergère, which he hung over his piano. (At the time of his death in 1894, Chabrier owned a small museum’s worth of significant art, including seven oils by Manet, six by Monet, three by Renoir, and one by Cézanne.)

Although Chabrier dabbled in composition from childhood and became a pianist of impres-sive virtuosity, at first he followed the family tra-dition and pursued law as his profession. He con-tinued to write music on the side while working as a civil servant in the Ministry of the Interior in Paris, but, in a sense, Chabrier only came into his own as a composer after hearing Tristan and Isolde in Munich in 1880. He resigned from the ministry later that year, became a confirmed—if not obsessive—Wagnerian, and decided to devote the rest of his life to composition. It was España, however, a very non-Wagnerian musical postcard, that made him an overnight sensation.

W hile touring Spain, Chabrier filled his notebooks with details about the rhythms of Spanish dance music

(he concluded it was impossible to notate the actual rhythm of a malagueña); the cut of the dancers’ black felt hats; “the admirable Sevillan derrière, turning in every direction while the rest of the body stays immobile.” Near the end

COMPOSED1883

FIRST PERFORMANCENovember 4, 1883; Paris, France

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCESJanuary 25 & 26, 1895, Auditorium Theatre. Theodore Thomas conducting

July 9, 1936, Ravinia Festival. Hans Lange conducting

MOST RECENT CSO PERFORMANCESJuly 13, 1991, Ravinia Festival. Gennady Rozhdestvensky conducting

February 23 & 24, 2012, Orchestra Hall. Alain Altinoglu conducting

June 20, 2012, Orchestra Hall. Edwin Outwater conducting (Donor Appreciation concert)

INSTRUMENTATIONtwo flutes and piccolo, two oboes, two clarinets, four bassoons, four horns, two trumpets and two cornets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, triangle, snare drum, bass drum, cymbals, two harps, strings

APPROXIMATE PERFORMANCE TIME6 minutes

CSO RECORDING1961. Andre Kostelanetz conducting. Video Images (video)

3

Alberto GinasteraBorn April 11, 1916, Buenos Aires, Argentina.Died June 25, 1983, Geneva, Switzerland.

Harp Concerto, Op. 25

In his native Argentina, Alberto Ginastera was recognized as a major composer from the first public performance of his music. His ballet suite Panambí was an overnight sensation when it was played at the Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires in

1937; the complete ballet was successfully staged three years later. (Ginastera eventually destroyed all of his scores composed before Panambí, giving the impression that he burst on the scene a fully formed talent.)

In 1941, the U.S. government sent Aaron Copland, a brand-name composer as American as hot dogs and baseball, on a good-will, fact-finding tour of Latin America. Before Copland left—his itinerary planned by the Committee for Inter-American Artistic and Intellectual Relations (its title a marvel of high-handed bureaucratic prose)—he agreed to take careful notes so that he could give a full report and recommend composers

for study in the States. His diary entry for September 26 reads:

There is a young man here who is gener-ally looked upon as the “white hope” of Argentine music. He is now twenty-five and is certainly the first candidate for a trip to the States from any standpoint. Alberto Ginastera would profit by contacts outside Argentina. He is looked upon with favor by all groups here, is presentable, modest almost to the timid degree, and will, no doubt, someday be an outstanding figure in Argentine music.

But Ginastera was slow to make his entry into the musical life of the United States. In 1941, the success of Panambí persuaded Lincoln Kirstein to commission a ballet from Ginastera for the American Ballet Caravan, a company he was then managing for George Balanchine. But by the time Ginastera had completed Estancia, the troupe had disbanded and the premiere was off. (Estancia wasn’t staged for another ten years, even in Argentina; the complete original score

of the Spanish tour, Chabrier wrote home to his friend, the Wagnerian conductor Charles Lamoureux, that as soon as he returned to Paris he intended to compose an “extraordinary fanta-sia”—a reminiscence of the music and dance that he had found so intoxicating in Spain. It would,

he promised, incite the audience to a fever pitch of excitement. Chabrier began the piece as a work

for piano duet—it was called Jota, after the lively Spanish dance—but soon realized he would need the full range of orchestral colors to do justice to his vivid memories. España, as the piece was finally called, is not only full of memorable folklike tunes, but it also benefits from Chabrier’s keen attention to the rhythmic patterns of Spanish dance. As the composer predicted, España was a great success from the start—it was encored at the premiere and was praised by com-posers as different as Manuel de Falla (who knew a thing or two about authenticity in Spanish music) and Gustav Mahler (who conducted España on several occasions). Even Chabrier, however, cannot have imagined the popularity its main theme would achieve seventy-three years later as a Perry Como single on the Hit Parade.

Charles Lamoureux

4

COMPOSED1956–1964

FIRST PERFORMANCEFebruary 18, 1965; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCESOctober 16 & 17, 2003, Orchestra Hall. Sarah Bullen as soloist, Daniel Barenboim conducting

INSTRUMENTATIONsolo harp, two flutes and piccolo, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, timpani, percussion, celesta, strings

APPROXIMATE PERFORMANCE TIME21 minutes

wasn’t played in the United States until 1991, although by then a suite of dances from the ballet had become popular concert fare.)

In 1942, Ginastera was awarded a Guggenheim Foundation grant to visit the United States, but the trip was postponed because of the war. Finally, in 1945, the com-poser and his family came to this country as temporary political refugees following Perón’s assumption of power. This was the first of many visits. For sixteen months beginning in December 1945, he lived and composed in the United States; he spent the summer of 1946 at Tanglewood, where he again met up with Copland. Ginastera continued to roam, but after Perón was removed from power in 1955, he returned to Argentina, where he became an indispensable part of the country’s cultural life.

U nlike nearly every other composer drawn to the concerto form, Ginastera began by writing one for the harp. (He went

on to write concertos for more familiar subjects: piano, violin, and cello.) The idea of a harp concerto came from Edna Phillips, the first harp of the Philadelphia Orchestra, who, along with her husband Samuel R. Rosenbaum, com-missioned a work from Ginastera in 1956. “I could hardly dream that it was going to be the most difficult work I have ever written,” the composer later confessed, “and that it would take several years to see the light.”

Ginastera began sketching the new concerto in 1956, but by the time he had finished it in 1964, Phillips had retired. (Although she never played Ginastera’s score—the 1965 premiere was given by the big-name international soloist Nicanor Zabaleta—Phillips claimed it was the best of the many works for harp that she and her husband had commissioned over the years.)

Ginastera wanted to write a concerto that extolled virtuosity and challenged the performer, but he quickly realized that the harp presented difficulties for a mid-twentieth-century composer:

The special features of harp technique—so simple and at the same time so complicated—the possibility of writing for twelve sounds on only seven strings, the eminently diatonic nature of the instrument, and many other problems make writing for the harp a harder task than writing for piano, violin, or clarinet.

In the end, he spent eight years (and com- posed two other concertos, one for piano and another for violin) before he was satisfied that the harp part was not only virtuosic, but playable—not only colorful and imaginative, but idiomatic.

G inastera writes three movements. The first charts an unexpected course: it begins with fiery, percussive music, but

gradually becomes more conversational, lead-ing to a soft, dreamy close. The harp interjects itself into the dancing rhythms of the opening and plays nearly nonstop. The harp writing is brilliant and challenging throughout (although it’s very different from the avant-garde pyro-technics of Berio’s Sequenza II, the landmark harp monologue composed at the same time).

Edna Phillips

5

Gustave CharpentierBorn June 25, 1860, Dieuze, Moselle, France.Died February 18, 1956, Paris, France.

Impressions of ItalyPerformed as part of the CSO Premiere Retrospective

“Perhaps on the whole, the most enchanting place in Rome,” the thirty-year-old Henry James said after he visited the Villa Medici in 1873. High on the Pincian Hill, overlooking a sea of red-tiled roofs and domes, the villa was built by

Cardinal Ferdinando de’ Medici in the 1570s to house his collection of classical statuary. Today it sits amid the only remaining Roman Renaissance garden with its original ground plan, and so one can still follow the same garden paths as Velázquez, who painted there in 1630, or one of the winners of the Prix de Rome, including Gustave Charpentier, who took up residence there in 1887.

The celebrated Prix de Rome was a scholarship established in 1663 that enabled young French artists—initially painters and sculptors—to study at the French Academy in Rome for three to five years. The academy, which was closed during the French Revolution, has been housed in the Villa Medici ever since it reopened in 1803. That year, for the first time, the academy began awarding prizes to composers, and it continued to do so nearly every year until 1968, when André Malraux, the French minister of

culture, discontinued the honor. The names of most of the winners mean nothing to us today, and Maurice Ravel is the most famous of those who attempted—five times, in his case—and failed to win the coveted award. Among the few nineteenth-century Prix de Rome winners whose music is still performed are Berlioz (in 1830, the year his Symphonie fantastique made him famous); Gounod; Bizet; Debussy; and, in 1863, Massenet, who later became Charpentier’s teacher.

Charpentier joined Massenet’s composition class at the Paris Conservatory in 1884, the year Massenet’s most enduring work, the opera Manon, premiered at the Opéra-Comique. Charpentier had been encouraged to pursue a career in music by both his father and grandfa-ther. He studied violin, first in Lille, and then, beginning in 1879, at the conservatory in Paris, where he eventually decided to become a com-poser. Didon, a cantata (or, as the score indicates, lyric scene) he wrote under Massenet’s care, won him the Prix de Rome in 1887. Although he moved to Rome reluctantly—and, like Debussy before him, returned home to Paris often during his three-year residency, Charpentier’s Italian sojourn turned out to be the most productive period of his career. The core of his life’s work was accomplished at the Villa Medici: these Impressions of Italy that Theodore Thomas and

The movement recalls the “objective nation-alism” of Ginastera’s earlier works, because of its debt to Argentine folk song (it also relies heavily on the contrast between 3/4 and 6/8 time that characterizes much Latin American music). But at the same time, it’s steeped in the international language of modernism.

The slow movement begins as a dialog between low, somber strings and harp. Ginastera has a remarkable ear for atmosphere and delicate sonorities. The heart of the music is as mysterious

and elusive as one of Bartók’s famous pieces of night music.

The solo harp launches the final movement with a large, rhapsodic cadenza characterized not just by display and special effects (glissandos played with the fingernails, “whistling sounds”), but by the greatest imaginable contrast, from single bell-like tones to powerful chords and great sweeps of sound. Once the orchestra enters, the music settles into a wild, driving dance that carries straight through to the very end.

6

COMPOSED1889–90

FIRST PERFORMANCEOctober 31, 1891; Paris, France (finale only)

March 31, 1892; Paris, France (complete)

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCESU.S. premiere November 24 & 25, 1893, Auditorium Theatre. Theodore Thomas conducting

MOST RECENT CSO PERFORMANCESNovember 3, 4 & December 14, 1937, Orchestra Hall. Frederick Stock conducting

INSTRUMENTATIONthree flutes and piccolo, three oboes and english horn, three clarinets and bass clarinet, soprano and alto saxophones, four bassoons, four horns, four trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, two harps, strings

APPROXIMATE PERFORMANCE TIME32 minutes

the Chicago Symphony would introduce to America in 1893; a “symphonie-drame,” La vie du poète (a sui generis score in the mode of Lélio, the Berlioz work that Riccardo Muti led in Chicago in 2010); and the libretto and the first act of his most famous work, the opera Louise.

Following the success-ful premiere of Louise at the Opéra-Comique in 1900, Charpentier risked becoming known as a one-work composer, like Chabrier. The opera’s tale of forbidden love and bohemian adventure, set to a score of sumptuous lyricism—the soprano aria “Depuis le jour” in particular—captured the imagination of an entire generation. Louise was performed one hundred times during its first sea-son and more than a thousand times by 1935. A film version of the opera, produced with the com-poser’s supervision and starring Grace Moore, was released in 1938. Louise overshadowed everything else Charpentier wrote, including, most painfully, a sequel, Julien, which was an immediate flop in 1913. In time, Louise, like many sweepingly popular artworks from bygone eras, faded from public view. The last staging at the Metropolitan Opera was in 1949. No major American company has produced the work since the San Francisco Opera’s revival in 1999, with Renée Fleming singing the title role for the first time. “Depuis le jour” remains a popular soprano showcase, but those five minutes are all that today’s public ever hears of Charpentier’s entire output.

I mpressions of Italy has shared a similar fate to Louise. The piece that introduced Charpentier to music lovers nearly a decade

before Louise, and the score that is considered the composer’s most successful instrumental work, it enjoyed great success with audiences up to World War II. In 1909, music critic Georg P. Upton included it in his book of Standard Concert Repertory, which it was at that time. After giving the U.S. premiere in 1893, the Chicago Symphony played Impressions of Italy often during its first fifty seasons, but it has not performed the score since 1937. In an era that prized pictorial realism, evocations of atmo-sphere, and depictions of local color, Impressions of Italy was an audience favorite and a work of delightful, unassuming charms. Today, it is a souvenir of the age before globalization, when travel was still a rare romantic adventure and when each destination was distinctive and, in fact, unique. Impressions of Italy is an ode to

View of the Villa Medici and its garden in Rome, engraving by Giovanni Battista Falda.

7

the spirit of place—and remembrance of the once-grand tradition of musical travelogues.

L ike Mendelssohn’s Italian Symphony, Tchaikovsky’s Capriccio italien, Strauss’s Aus Italien, and Elgar’s In the South

(Alassio), Charpentier’s score is the work of a visitor intoxicated by Italy. Charpentier leaves us with five “impressions,” each a picture of indelible scenes from Italian life as viewed by a fascinated bystander. The first is a sere- nade. It opens with an ardent unaccompanied song in the cellos that, joined by strings and harps evoking the sound of strumming guitars and mandolins, grows more passionate until it dies away in the night air. The second is a lovely scene by a fountain. A solo oboe sets the mood, tender and reflective. The next impression takes us into the mountainside: the steady procession on muleback is intercut with village tunes and pastoral calm. The fourth picture is wonderfully evocative of the great expanses viewed from the mountaintops—with distant bells and bird song—all encompassed by a grand, swelling melody. Finally, in his most fully realized portrait, Charpentier takes us to Naples, a city that is still so simultaneously chaotic and intoxicating that Elena Ferrante, the author of today’s acclaimed Neapolitan novels, calls it “the best and worst of Italy and the world.” Clearly, Charpentier was both overwhelmed and enraptured with what he found there. “Naples is a city in which many worlds coex-ist,” Ferrante says, and Charpentier set out to capture as much as he could of its richness and complexity. This is music of abundance, full of

song and dance (the tarantella, in particular), of both urban bustle and personal reflection, and of the sorrow and sweetness of life.

C harpentier was so filled with Italian impressions that he wrote a second suite of orchestral sketches in 1894; the score

apparently was destroyed by fire and never per-formed. In 1911, Charpentier composed one final purely orchestral work, a symphonic poem titled Munich. (He lived another forty-five years.) It was intended to be the first in a series of “souvenirs de voyage,” continuing with Prague, Vienna, and Monte Carlo, but Charpentier got no further than Munich, apparently not finding in those destina-tions the same inspiration that struck him in Italy.

A postscript. Charpentier came to the U.S. for the first time in December of 1913, only weeks after Theodore

Thomas gave the American premiere of the Impressions of Italy in Chicago. Charpentier told The New York Times that, if he could find a suitable theme, he hoped to write an opera set in America. (He did not.) Shortly after his arrival in New York, he introduced a new ballet staging of the Impressions of Italy, set on a Neapolitan terrace. In his scenario, Daisy, a young American girl, is overcome by the charms of Italian life and falls in love with Pietro, a mandolin player. Juana, a local girl, is already in love with Pietro, and when he rejects her for Daisy, Juana stabs Daisy in the middle of a grand Neapolitan party. As the dancing continues, Daisy dies while Pietro kisses her one last time.

8

Maurice RavelBorn March 7, 1875, Ciboure, France.Died December 28, 1937, Paris, France

Boléro

One of the most famous pieces ever written, Boléro began as an experiment in orchestration, dynamics, and pacing. Ravel was quick to tire of his exercise—he once said that, although people thought it his only masterpiece, “Alas, it

contains no music.” But he didn’t object to being famous.

Late in 1927, Ravel accepted a commission from Ida Rubinstein and her ballet company to orchestrate six piano pieces from Albéniz’s Ibéria as a sequel to his brilliant scoring of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition. But when Ravel returned from his whirlwind concert tour of America and encountered problems with the exclusive rights to Ibéria, he dropped the project and instead chanced upon a tune with “a certain insistent quality” that became Boléro. “I’m going to try and repeat it a number of times without any development, gradually increasing the orchestra as best I can,” he remarked at the time, and that’s precisely what he did.

Boléro was an immediate success as a ballet, but its real heyday started after Rubinstein’s exclusive rights ran out and the first concert performances began. Ravel was embarrassed by its popularity:

I am particularly anxious that there should be no misunderstanding as to my Boléro. It is an experiment in a very special and limited direction, and it should not be suspected of aiming at achieving anything different from, or anything more than, it actually does achieve. Before the first performance, I issued a warning to the effect that what I had written was a piece lasting seventeen minutes and consisting wholly of orchestral texture without music—of one long, very gradual crescendo. There are no contrasts, and there is practically no invention except in the plan and the manner of the execution.

One can imagine Ravel’s dismay when he realized that this was the music that would carry his name around the world. Shortly before he died in 1937, he summoned the strength to travel to Morocco, where, among the sounds of Moorish and Arabic street music, he was shocked to hear a young man whistling Boléro. But, while Boléro is by no means his most accomplished or sophisticated work, it is, like every single piece in the Ravel canon, impeccably detailed and polished music. (In forty years, Ravel only wrote about sixty works, nearly all of which belong in the standard repertoire—an almost unparalleled achievement.) The first tune, stated by the flute, is as familiar as any melody in music, yet how

COMPOSEDJuly–October 1928

FIRST PERFORMANCENovember 22, 1928; Paris, France (as a ballet)

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCESMarch 21, 22 & 25, 1930, Orchestra Hall. Frederick Stock conducting

July 24, 1938, Ravinia Festival. Eugene Goossens conducting

MOST RECENT CSO PERFORMANCESSeptember 14, 15 & 16, 2007, Orchestra Hall. Riccardo Muti conducting

August 7, 2013, Ravinia Festival. Carlos Miguel Prieto conducting

INSTRUMENTATIONtwo flutes and two piccolos, two oboes, oboe d’amore and english horn, two clarinets, E-flat clarinet and bass clarinet, two bassoons and contrabassoon, soprano and tenor saxophones, four horns, three trumpet and piccolo trumpet, three trombones, tuba, timpani, two snare

drums, cymbals, tam-tam, celesta, harp, strings

APPROXIMATE PERFORMANCE TIME17 minutes

CSO RECORDINGS1966. Jean Martinon conducting. RCA

1976. Sir Georg Solti conducting. London

1991. Daniel Barenboim conducting. Erato

9

Maurice Ravel’s only appearances with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra were on January 20 and 21, 1928, at Orchestra Hall. He conducted a program of his works, including Sheherazade (with mezzo-soprano Lisa Roma), Daphnis and Chloe Suite no. 2, Le tombeau de Couperin, La valse, and his orchestration of Debussy’s Sarabande and Dance. According to the review in the Chicago Tribune, “the audience cheered M. Ravel again and again, and at the end of the program the Orchestra, incited thereto by the audience and by the music it had been playing, gave him a prolonged and enthusiastic fanfare.”

Composers in Chicago

many of us could accurately sing it from memory, precisely following its unpredictable, sinuous curves and recalling the ever-fresh sequence of long and short notes. Certainly the second tune, a free and supple melody introduced by the high bassoon, has an elusive, almost improvisatory quality.

Ravel proceeds with his exercise, stating the first tune twice, then the second one twice, and so on back and forth, each time adding new

instruments not just to effect a gradual crescendo, but to create an astonishing range of orchestral colors. Just before the end, Ravel’s patience sud-denly wears out, and he makes a sudden swerve from a steady diet of C major into E major, upsetting the entire structure and toppling his cards with the sweep of a hand.

Phillip Huscher has been the program annotator for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra since 1987.

© 2015 Chicago Symphony Orchestra