Onbigdrawings issu

-

Upload

ad-gallery -

Category

Documents

-

view

222 -

download

2

description

Transcript of Onbigdrawings issu

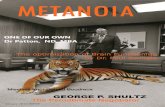

Neville GabieExperiments in Black and White, 2012/13Video still of performance at Cabot Institute Bristol University

1

On Big DrawingsCurated by Friedhard KiekebenOctober 2 – November 1, 2014Reception: October 2, 5-7 PM

Neville GabieCharles MahaffeeMichael K. PaxtonOlivia PetridesDeb SokolowChristine WallersMatthew Woodward

ar t + design

A + D AVERILL AND BERNARD LEVITON

A+D GALLERY

619 SOUTH WABASH AVENUE

CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 60605

312 369 8687

COLUM.EDU/ADGALLERY

GALLERY HOURS

TUESDAY–SUNDAY

12PM–5PM

THURSDAY

12PM–7PM

This project is partially funded by a grant from the Illinois Arts Council Agency and the Elizabeth Firestone Graham Foundation.

2

Deb SokolovListen to the Squatter, 2013From Several Mysteries Acrylic, graphite, tape, photo collage on paper17” x 11”

3

Introduction

On Big Drawings brings together artists whose work celebrates the medium of drawing as a contemporary form of expres-sion in a number of ways and with unique approaches. The chosen works are predominantly large-scale, site-specific, and immersive, challenging traditional notions of what “drawings” are in the contemporary context. Also included are smaller scale works such as Deb Sokolow’s series of Mysteries, for instance, Listen to the Squatter, shown on the opposite page.

Internationally, works by Julie Mehretu, Kara Walker, William Kentridge, and Julian Opie, or the thickly textured black and white drawings by Richard Serra, showcase the strong current interest in an expanded–and expansive–notion of the medium of drawing. Sol LeWitt famously redefined the conventions of drawing, and the purpose of drawing, in his series of Wall Drawings.

During preliminary research we were looking for artists working in the Chicago area whose graphic work may be conceptually driven, abstract, three-dimensional, installation-based, or narrative. It seemed important that the selected works showed notions of “trace,” “marks and signification,” “process,” “mediation,” and “representation” in a way that typifies the graphic medium as being quite distinct from painting, but would challenge preconceived and traditional ideas of what a “drawing” is, and what it possibly could be.

The seven artists in this exhibition all made a unique contribution to “expanded drawing,” and their work creates a dialogue across media boundaries.

Originally we envisaged to also extend the exhibition into public sculpture and outdoor installation (also including works by Jeff Harms and Daniela Ehemann) but we had to limit the three-dimensional aspect to one indoor drawing/sculpture project, which will be Christine Wallers new site-specific installation On the Elements of Electricity, a poetic meditation on light, line, and electricity. The show we curated is now a more classical gallery exhibition, which we believe serves its purpose of “Big Drawing” equally well and in a beautiful setting.

My personal interest in the medium of drawing re-emerged through a long-standing dialogue with Jennifer Shaw since the year 2000, and through links between drawing, digitality, and multiplicity (which is my more native creative domain). Between 2008 and 2012 I realized a series of digital wall drawings that were printed in vinyl, immersive and on a large scale, such as Pillar Wrap, Tumble, and Loop.

These projects made me think of connecting with other artists keen on expanding drawing beyond the sketchbook, and the idea for On Big Drawings was born. I am very grateful to all the participating artists for their support and enthusiasm; and this project would not have been possible without the generous support from the Columbia College A+D Gallery who is hosting this exhibition. Special thanks goes to the gallery director Meg Duguid who added her curatorial genius, to Jennifer Shaw for writing a poignant and captivating introductory essay, as well as to the Elizabeth Firestone Graham Foundation who generously supported the production of this publication.

Friedhard Kiekeben,Chicago, 2014

Friedhard Kiekeben is an artist; he studied at the Royal College of Art and works as Fine Art faculty at Columbia College Chicago.

Pillar Wrap, Public Art Commission, Harrison Gateway, Chicago, 2008

5

THE ARTISTS

Neville Gabie Page 12

Michael K. Paxton Page 16

Deb Sokolow Page 20

Charles Mahaffee Page 24

Olivia Petrides Page 28

Christine Wallers Page 32

Matthew Woodward Page 36

6

On Big Drawing

Something has happened to drawing. It has been snatched back from the amateur sketcher and the art school copyist; excused from the politeness of the drawing room and the perfunctoriness of the drawing board. Used for so long to outline form in nature – to describe an apple or the musculature of a classical torso – it is no longer just a stage before coloring in. Any requirement to merely give a perspective line has been waived. Its down-and-out days in the pissed-up subways of the anti-social behaviorist are similarly in question. In the work of the seven artists in this exhibition, drawing appears to have opened up a new space between the lyrical and the epic. Scaled up to the proportions of Renaissance fresco, Romantic history painting and Expressionist panorama, it has gone beyond the sketchbook page. Drawing has gone BIG.

Drawings have commonly been the maps from which to understand or relate to what we see in the world. They might be realistic, architectural or expressive in style; but essentially they have helped us pin something down or represented an enactment of that very process of refinement. The drawings by these artists are not diagrams or blueprints for something else; they are all in some way acts in graphite, ink or chalk: the drawing as verb. Each of them, in turn, eschews the traditional notion of drawing as an ancillary art form pointing to future outcomes in other media. Rather, these artists in their own different ways foreground drawing as the engine of ideas that are themselves the finished artifact.

Drawing as an act of Penitential Endurance: Neville Gabie Drawing as an act of Incarceration: Michael K. Paxton Drawing as an act of Investigation: Deb Sokolow Drawing as an act of Pseudo Writing: Charles Mahaffee Drawing as an act of Industry: Olivia Petrides Drawing as a Three-Dimensional act: Christine Wallers Drawing as an act of Archaeology: Matthew Woodward

Endurance: Neville Gabie

I must not be deceitful. I must not be deceitful. I must not be deceitful. I must not be deceitful.I must not be deceitful. I must not be deceitful. I must not be deceitful. I must not be deceitful.I must not be deceitful. I must not be deceitful. I must not be deceitful. I must not be deceitful.I must not be deceitful. I must not be deceitful. I must not be deceitful. I must not be deceitful.

Watching Neville Gabie’s Experiments in Black and White VII – a piece created in video and chalk – engenders the same sense of schadenfreude to be had from watching the deceitful Sisyphus rolling his boulder endlessly up the hill. Gabie’s drawing task (akin to the punishment of “doing lines”) is to manhandle an immense rock of chalk across a blackboard of equally immense proportions. Line by line he draws, or rather hauls, the chalk across the board. Is this what big drawing means: a muscular feat of strength and determination as much as the dexterity of draughtsmanship? Arduous toil rather than the flourish of pen and wash? Without doubt, this piece reminds us of the redefinition of drawing that has occurred in recent times.

Although Gabie’s big drawing bears the mark of a man enslaved, it also results in a landscape which is nuanced and delicate in its accomplishment. The toil of its own execution leaves the piece when the artist, his black suit soiled by the chalk, leaves the scene. The effect is as of a furrowed field or wind-blown body of water. The problematized satisfaction derived from the choice of drawing medium is rooted in our knowledge that the blackboard rubber will inevitably wipe it away and Sisyphus will need to begin again. We are also forced to consider the ephemeral nature of a drawing in a different way; since we know that this giant chalkface drawing only exists as a record on film. It is process and its associations – the interplay between permanence and impermanence – that are the point here, not the finished drawing.

7

Incarceration: Michael K. Paxton

Whilst Gabie’s act of obedient penitence has a classical proportion and poetry to it, Michael K. Paxton’s big drawings have the edginess and anger of a man in solitary confinement. Here, drawing has taken place under duress, and seemingly with whatever basic means were available. Walls and excrement are the materials of the insane asylum or “dirty protests” against unjust detention, and these works thrash about and rage against the limitations of ordinary drawing. The artist is in fact using traditional means – wash drawings – but on a life-sized scale and with an attitude very different to the practice of the polite societies of the 18th and 19th centuries, when Jane Austen heroines whiled away their languorous afternoons with pen and wash as a means of enriching their social dowry through outward signs of “accomplishment:”

no one can be really esteemed accomplished who does not greatly surpass what is usually met with. A woman must have a thorough knowledge of music, singing, drawing, dancing and the modern languages, to deserve the word... Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice, (1813)

The “improving” nature of drawing is something that is outmoded today, and yet there remains a strain of this notion in the idea that a good work ethic in the art of drawing will be the basis of good art. Drawing as the armature for color. Drawing as a way to understand forms and how they relate. Drawing as a geometric formula with which to create the illusion of depth. Paxton is not concerned with drawing either as an exercise in etiquette nor as a stage in a training regime. His is rude drawing, immediate and unconstrained by the courtesy and corsetry of drawing decorum. Although his gestural marks could be termed sketch-like, the scale of these pieces and the force behind them contradicts the received notion of sketching as a preparatory act of drawing. To sit and sketch conjures up images of the artist with his sketchbook in quiet experimentation, not lashing around the walls. Here, the gentility and self-control of tradition is atavistically by-passed and drawing unleashed once more into primitive form.

Investigation: Deb Sokolow

With the OCD of a crazed fan, Deb Sokolow finds out about people and situations and processes them into oblique narratives of hand-written captions and hand-drawn vignettes, tables and graphs. Flip chart brainstorming and Post-it Note scraps are the artist’s source material. Part archive, part forensic investigator’s incident board, these quirky semi/fictional biographies grow to hundreds of feet in length. Sokolow’s pages are not sewn neatly together in a convenient book form. Paper ephemera is pasted in long sequences around the walls of the gallery or inserted into museum vitrines as evidential objects or as archaeological finds excavated from filing cabinet and briefcase. Walking the length of the subject creates a selective relationship to it, different to information received in a sedentary way. Storyboards are transcribed directly onto the walls and inset with interactive elements or accommodate existing gallery furnishings, such as light switches, as active choices for the participating reader/viewer. Like Alice, we follow a corridor-length flow diagram that tells you to “start here,” “press this,” “choose an ending.” The cartography of call out boxes and the calligraphy contained within creates an experience of visual and literary density. What’s here implied is that the transient DNA of our temporal identity transfers itself to the very surface of the million things with which we come into contact each day; and that this can somehow be tracked-down, reconstituted and revivified in artworks such as these.

Is this act of idiosyncratic social anthropology to be classified as drawing rather than creative documentation? When most of our words are keyed through computers and phones, the handwritten acquires a novelty and materiality which renders the artist’s heavy black crossings out and punctuation marks a formal value as much as communicative meaning. The use of crude capitalization and wonkily ruled lines affirms an individual maker rather than a word-processor. Sokolow’s is a whimsical, homespun style of “drawing” which has found a cult following for artists like David Shrigley, whose black humor bon mots and “inept” doodles have a kick because of their disarmingly faux naivety. It also serves to remind us that drawing is continuously mutable and constantly adapts itself to new forms and emerging technologies, even if that adaption is itself a form of reaction.

8

Writing: Charles Mahaffee

The process of drawing is, before all else, the process of putting the visual intelligence into action, the very mechanics of visual thought. Unlike painting and sculpture it is the process by which the artist makes clear to himself, and not to the spectator, what he is doing. It is a soliloquy before it becomes communication. Michael Ayerton

Drawing is a species of writing. Traditionally it has used the same implements. The artist or author takes up a pen and makes marks on a sheet of paper – he may produce marks that are formal and called “drawings” or marks that carry meaning and are called “words. ” Artists like Deb Sokolow position drawings and words together in a presentational art in which the writing has aesthetic qualities but which is ultimately comprehensible. Charles Mahaffee creates a more fully refined hybrid of the drawing-writing animal. It looks like drawing but you think you might be able to read it. It looks like writing but you can’t quite read it. A graphite gray area. Is Mahaffee a calligrapher or a poet, a graffiti artist or protestor, an abstract painter, a scribbler?

In netting characters from the domain of words that are really only the traced shape of characters or mock letters, the work interrogates itself as to its own status as doodling or pseudo-writing. Or is it simply the self-conscious arrangement of bad handwriting? The viewer strains, thinks he sees a message in the densely worked strokes for a moment before it morphs back into an abstract patterning. The forcefulness of Mahaffee’s black marks would suggest more than pattern is intended. The fact that any clear meaning is not fixed, not overtly stated, gives it an insidious power – a multi-layered possibility of significance akin to poetry.

Whilst Sokolow’s use of writing is more in the line of graphic novel dialogue boxes giving clear character descriptions and plot direction, Mahaffee uses the aesthetic of words and characters as the units with which to construct a pattern which may or may not have direct syntactical meaning. It forces us to consider a more complex relationship between the word as signifier of meaning and the word as vehicle of form. Word forms corralled together build into a fence-like structure. Perhaps each stroke is a day spent in a solitary cell, a mark of time scratched into the wall. Or is it a scream for attention made emphatic through repetition? Mahaffee’s work forces the viewer to oscillate between attempting to understand what the repeated words and blocks of words are saying and what they look like, apart from any translated meaning. In doing so, he is actually taking drawing back to one of its earliest traditions with its roots in eastern calligraphy. Just as we can appreciate the beauty of Japanese calligraphy for its delicate strokes and rhythms of the characters as a block formation, therefore, we can also appreciate the sloganeering power of Mahaffee’s sign-writing.

A pencil can become a guerrilla weapon – it’s small, cheap, easily transportable, quick to deploy and can have a powerful impact. In a world of depressed markets, economic decline and reduced horizons, then, drawing retains a DIY-punk vitality and can do big things in the right or wrong hands.

Industry: Olivia Petrides

人心齐,泰山移 rén xin qí, tài shan yí -

When people work with one mind, they can even remove Mount Taishan

Chinese Proverb

Through the accumulated bundling of lines and cross-hatching, Petrides takes the possibility of an epic lyrical drawing to phenomenal proportions. We have seen how the persistence of the artist can transform a blackboard into a lesson in linearity and how drawing with an expansive energy can generate immense gestural marks. Here it is a demonstration of how techniques traditionally used on a small scale can be applied, through industry and dexterity, to make something at once minute in perfection and monumental in impact.

9

The bigness of nature has been a subject deemed worthy of a grand scale treatment in painting since the 18th century when artists like Thomas Cole and Thomas Moran created monumental canvases of vast tracts of the American wilderness. It was Cinemascope big screen, big country, before the movies even arrived, and they held the viewer spellbound, continuing to do so today. The sublime panorama was awe-inspiring but also terrifying in its immensity. An English landscape seldom threatens its painters and poets like the vast tracts of prairie, the parched canyons, scalding geysers and endless forest ridges of the unchartered territories. The threat of being lost is inherent in those paintings. But the medium of drawing has seldom been thought appropriate as the means to the monumental. Paint can cover much more ground with much less effort. It can render scenes in Technicolor, so why use the single stroke of the pen to build something so big?

As an artist-in-residence at a settlement in the Arctic Circle, Petrides’ aim was to set down on paper both the micro and macrocosmic essence of the aurora borealis. This was not about showing the generalized effects of nature’s light show from a distance with the broadness of paint. This was about being inside its suffocating gaseous mass. Each element marked down. Her drawings intimidate you with the raw power of nature. Great surges of line suck you into a lava flow or make you disappear into a whiteout. Her elemental landscapes move and breathe and curl around you – at once so big as to make you lose your bearings in them, and yet at the same time with a detail of line that recalls the individual hairs on a wolf ’s back. The monochrome interplay between ink and paper only serves to heighten the special effects, like the moodiness of an Ansel Adams photograph in close-up panorama. With its awe-inspiring levels of unique detail and saturated human attention, Petrides’ work also reminds us of the recent tendency towards privileging drawing’s analogue and organic qualities over the reproductive ease of digital media.

Three-Dimensional Drawing: Christine Wallers

Wallers’ two-dimensional drawings have a density that is entirely formal. Rich in mark making but essentially delicate and fugitive in a way that is only possible with graphite, we feel that a moment of form will disappear in an instant – erased and replaced with another accumulation of marks. In her paper-based series, marks swarm or flock together to produce a powerful collective body which moves as a single entity, but in which each mark has its own weight and importance.

Over the last few years I have produced a series of dense and tightly knit drawings that emphasize process, structure, repetition and random patterning. Different values or intensities of graphite line build an ethereal scaffold that can vibrate as an unsettling mass. Christine Wallers

But the artist is not constrained by definitions of drawing to the use of graphite, chalk, or charcoal. In her installations she substitutes the drawn line with threads, filaments and wires. Bundling these together, she creates line in 3D as if transposing the scaffolding to the physical space of the subject itself; thereby fusing the polarities of object and process. That it is still technically a drawing and not a sculpture is up for debate. Certainly, such site-specific and performative dimensions to Wallers’ practice tend to blur boundaries between drawing and plastic arts. The delicacy of the choice of material and its regularity, though, recall the simplicity and economy of graph paper: a Sol LeWitt in air, a perspective structure for its own beauty, rather than as the guidelines for the drawing of something else. Wallers generates scale by multiplicity, strength through number and in her installations, at least, takes on the projective condition of drawing literally.

It retains the linearity (first and foremost) as well as the immediacy and accessibility that characterizes drawing. Like stringing a giant harp, Wallers delineates space, and physically conducts (rather than implies) the passage of light and the aural resonance of strummed chords. This is something new for drawing. The parallel fibres don’t simply represent vectors, they function as actual musical staves, like blank sheet music in space which is activated by the play of light to produce the notes of the composition. Rulings are translated into something which seeks to draw attention to the space we inhabit. By drawing in 3D, Wallers can fill an entire room with the singing, oscillating beauty of line.

10

Archaeology: Matthew Woodward

So drawing need no longer have manners, but there are other conventions to throw off. Matthew Woodward succeeds in doing this whilst giving the nod to one of the principal roles for drawing in art schooling – as the medium for copying. Matthew Woodward shows that big drawing does not have to be big in gesture and emotion, but can exude an antique elegance with the stuff of dereliction. In his work we have a strangely pleasing mix of the reclamation yard, archaeology and the lair of the serial killer. It’s as though we have uncovered the delicate remains of a Roman villa wall painting in a seedy downtown warehouse. Gorgeously ornate architectural features are skillfully rendered on shabby polythene sheets.

The practice of copying classical moldings as a traditional apprenticeship collides with the rebellion of a modern artist and materials which cannot help but evoke time past and present. What we experience is something akin to discovering a Villa Farnesina at 25th and 41st. Woodward’s architectural motifs have the richness of the red chalk drawings that many of the Academy art students used when copying from classical casts and moldings. This isn’t the trompe l’oeil effect that the Roman frescoist was attempting, rather, he produces something that might once have been complete but which has become fragmentary over the years. It is as though the drawing presented has a past that has rubbed away at the edges and the artist’s preoccupation has precisely to do with this rub of the artifact up against the seasons and human contact.

In On Big Drawings then we see seven acts of drawing. Seven approaches in monumental scale. Seven artists testifying to the vitality, flexibility and relevance of a technique as old as mankind itself, as fresh as a child’s first marks. In the hands of contemporary practitioners, drawing has been set new tasks – of documentation and description; to carry words and forms on its back; to work with new technologies. It has not found itself inappropriately used or out of its depth. The doldrums of drawing are well behind us. No longer the slave of the academies or servant of fine ladies. Perhaps its power of endurance and reinvention lies simply in its simplicity, in its economy of means, and its multiplicity of purpose.

Jennifer Shaw

Jennifer ShawJennifer Shaw studied History of Art at St Andrews University and has a Masters Degree in Museum & Gallery Studies. She has worked as a curator and exhibitions coordinator in the UK and USA. Her interest in drawing stems from her early years as an art student and has persisted in her work with various collections and artists over the last 20 years. During this time she has been privileged to get a close up look at drawings of all shapes and sizes. She currently lives in Warwickshire, England.

13

Neville GabieExperiments in Black and White, 2012/13Video stills of performance at Cabot Institute Bristol University

15

Neville Gabie was born in 1959 in Johannesburg, South Africa and holds an MA in Sculpture from the Royal College of Art in London. He has held residencies across the globe, including Vitamin Creative Space in Guangzhou, China, and International Art Space in the remote town of Kellerberrin in western Australia. He has worked on a photographic project with the NGO ‘Right to Play’ and Art Review magazine in Afghan Refugee camps in Pakistan. Between 2010 and 2012, he was the Olympic Delivery Authority Artist in Residence at Olympic Park, and in 2012 was given a major commission by the Contemporary Arts Society of Nottingham, England. His work is included in the Arts Council and Tate Gallery collections.

Experiments in Black and White (oil) | Experiments in Black and White, Africa (ice)

17

Michael K. PaxtonRiven (installation view), 2012 Chalk, charcoal, gesso on wall14’ x 19’

Michael K. Paxton in front of Riven

18

Michael K. Paxton Piney Drawing 2, 2013 Pen and ink wash on drafting film 24” x 36”

Woods 2, 2011Pen and ink wash on drafting film24”x 36”

Red Drawing, 2014Pen and ink wash on drafting film25” x 40”

19

Michael K. Paxton is a sixth generation West Virginian and Chicago based artist. He has a BA in Art from Marshall University and an MFA in Drawing and Painting from the University of Georgia. Paxton has recently been awarded a fellowship by the Jentel Artist Residency Program in Wyoming, an Illinois Arts Council Professional Development Grant, Faculty Development Grants from Columbia College, Chicago and a Marshall University Alumni Award of Distinction presented by the Alumni Association in concert with the College of Fine Arts in Huntington, WV. In 2012 he completed an artist-in-residence with Air le Parc Project and Research Center in Pampelonne, France, he was a Visiting Artist with the School of Art and Design of Marshall University in Huntington, WV where he created a huge gallery size wall drawing installation Riven, and was included in the group exhibitions New Country at the Claypool-Young Art Gallery of Morehead State University, KY.

Piney Drawing 2 (detail)

21

Deb Sokolow Dear Trusted Associate, 2009/10Graphite, charcoal, ink, acrylic on paper and on wallApproximately 40’ long

22

Deb Sokolow is a Chicago-based artist whose text-driven drawings combine research, fiction and humor to speculate on topics relating to politics, conspiracy theory and human nature. Recent group exhibitions include the 4th Athens Biennale in Greece, The Drawing Center in New York City, Museum für Gegenwartskunst Siegen in Germany, The Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia and Western Exhibitions in Chicago. Sokolow’s 2013 solo exhibition at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Some Concerns About the Candidate, was reviewed in The New York Times. Her work has been reproduced for Creative Time’s recent comics project, for Swedish art magazine, Paletten, and in Vitamin D2, a recently released survey on contemporary drawing. She is a recipient of a 2012 Artadia award and residencies at Art Omi, Nordic Artists’ Centre in Norway, and Vermont Studio Center. Sokolow received her MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2004 and her BFA from University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 1996. She is a lecturer in the Department of Art Theory & Practice at Northwestern University.

Several Mysteries, 2013Suite of 23 drawingsAcrylic, graphite, tape, photo collage on paper17” x 11”each

(left)Two Men Suits

(right)Friendly Stranger

26

Charles Mahaffee was born in 1980 in Decatur, Georgia, has strong ties to Chicago, and currently lives and works in Doha, Qatar. His conceptually informed art practice encompasses drawing, video, and sound art. He earned both his BFA and MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. He has shown his work nationally and abroad in such venues as Lloyd Dobler Gallery, Hinge Gallery, Julius Caesar Gallery, MDW Fair, the NEXT exhibition at Art Chicago, and the Action Field Kodra Festival in Thessolaniki, Greece.

Attrition (detail), 2014 Charcoal on paper

27

Charles Mahaffee in his Chicago studio in 2013. Mahaffee has a strong conceptual background and studied postmod-ern theory; interestingly; the language aspect is shared by a number of the artists in On Big Drawings.

Life studies from the artist’s sketchbook, 2013

30

Olivia Petrides has had numerous exhibits in galleries and museums in Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Scotland, Seattle, Washing-ton, D.C., and Chicago. Her works are included in the public collections of the Smithsonian Institution, the United States Park Service, the Field Museum, the Illinois State Museum, Openlands Preservation Association, and Icelandís Hafnarborg Institute of Art, among others. She has received numerous grants and artist residencies, among which are a Fulbright Grant, American-Scan-dinavian Foundation Grants, and an Illinois Arts Council Governor’s Exchange Award. She has been awarded residencies at the Rekjavik Municipal Museum and the Gil-society in Iceland, the Faroe Islands Museum of Natural History, the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, the Vermont Studio Center, Yellowstone National Park, and the Ragdale Foundation. Petrides received her MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where she is currently an Adjunct Associate Professor in the Painting & Drawing Department and the Visual Communications Department.

Olivia Petrides in her Chicago studio, 2013

34

Originally from Chicago, Christine Wallers has lived, exhibited and curated shows in Seattle, New Mexico, France and Germany. Her work references an interest in natural phenomena, most notably light and water phenomena in the Northwest, the Southwest and the Midwest. She is a cross-disciplinary artist whose work uses formal procedures of minimal and post-min-imal art to craft installations that are site-specific, experientially-based and often fleeting. Within this she attempts to create an experience of the ephemeral, the just emerging and the barely visible from the interplay between object and space. Time and its shifts are key to understanding her process. Her work has been reviewed in Art in America, TimeOut Chicago, and featured in Dwell magazine. In addition, she has been a visiting artist at the Chinati Foundation in Marfa, TX.

Study for On the Elements of Electricity, a new site-specific work made for On Big Drawings, Chicago, 2014Fine gauge copper wire, punched steel, magnets, paint 86”x 12”

38

Matthew Woodward was born in Rochester New York in 1981. He received his BFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and his MFA from the New York Academy of Art. He has exhibited both nationally and internationally at venues such as the Chicago Cultural Center, Indianapolis Art Center, Janine Bean Gallery in Berlin, The Drawing Room in Budapest, Hungary, and New York Academy of Art. He has been in residence at the Vermont Studio Center, Urbanfuse Residency in Berlin, The Cill Rialaig Project in Ireland, and the South Logan Square Artists Coalition in Chicago. He is an instructor of Art at Dominican University and has given numerous lectures at schools and colleges throughout the United States. Currently, Woodward lives and works in Chicago and is represented by Linda Warren Projects.

Polk Street, 2014Mixed media on paper85’ x 101’

Matthew Woodward in his Chicago studio.

40

Olivia Petrides www.oliviapetrides.com

Christine Wallers www.christinewallers.typepad.com

Michael K. Paxton www.michaelkpaxton.com

Charles Mahaffee www.charlesmahaffee.com

Matthew Woodward www.mattwoodwardard.com

Deb Sokolow www.debsokolow.com

Neville Gabie www.nevillegabie

www.colum.edu/adgallerywww.onbigdrawings.com/

41

Christine Wallersthe white piece, 2012Charcoal, white pencil, powdered graphite, hand cut, on paper10” x 14”