'on the Origins of Dee’s Mathematical Programme' the John Dee–Pedro Nunes Connection

-

Upload

manticora-laudabilis -

Category

Documents

-

view

19 -

download

2

Transcript of 'on the Origins of Dee’s Mathematical Programme' the John Dee–Pedro Nunes Connection

Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 43 (2012) 460–469

Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect

Studies in History and Philosophy of Science

journal homepage: www.elsevier .com/ locate /shpsa

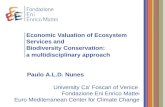

On the origins of Dee’s mathematical programme: The John Dee–PedroNunes connection

Bruno AlmeidaCIUHCT – Centro Interuniversitário de História da Ciência e Tecnologia, Pólo da Universidade de Lisboa, Faculdade de Ciências, Edifício C4, Piso 1,Gabinete 28, Campo Grande, 1749-016 Lisboa, Portugal

a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t

Article history:Available online 9 January 2012

Keywords:John DeePedro NunesNautical scienceMathematical programme

0039-3681/$ - see front matter � 2011 Elsevier Ltd. Adoi:10.1016/j.shpsa.2011.12.004

E-mail address: [email protected] Dee (1558). This book had one more known editio

Heilbron: Dee (1978). The text can be considered his firwas ‘in the main, a fully intelligible series of recipes fo

In a letter addressed to Mercator in 1558, John Dee made an odd announcement, describing the Portu-guese mathematician and cosmographer Pedro Nunes as the ‘most learned and grave man who is the solerelic and ornament and prop of the mathematical arts among us’, and appointing him his intellectualexecutor. This episode shows that Dee considered Nunes one of his most distinguished contemporaries,and also that some connection existed between the two men. Unfortunately not much is known aboutthis connection, and even such basic questions such as ‘What could John Dee know about this Portuguesecosmographer’s scientific work?’ or ‘When, why and where did this interest come about?’ still lack properanswers. In this paper I address this connection and examine Nunes’ influence on Dee’s mathematicalwork. I argue that Dee was interested in Nunes’ work as early as 1552 (but probably even earlier). I alsoclaim that Dee was aware of Nunes’ programme for the use of mathematics in studying physical phenom-ena and that this may have influenced his own views on the subject.

� 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

When citing this paper, please use the full journal title Studies in History and Philosophy of Science

1. Introduction

In 1558, John Dee (1527–1609) published his first work, Propae-deumata aphoristica.1 At the beginning of the book, Dee included adedicatory letter (dated 20 July 1558) to his friend, the Flemish car-tographer Gerard Mercator, in which he recalled the good times theyspent ‘philosophizing’ together in Louvain. He also justified the delayin the completion of his awaited scientific work, declaring that hadfallen severely ill in the previous year. Then, he makes an unex-pected statement:

You should know that, besides the extremely dangerous illnessfrom which I have suffered during the whole year just past, Ihave also borne many other inconveniences (from those who,etc.) which have very much hindered my studies, and that my

ll rights reserved.

n in the sixteenth century (Dee, 1568),st attempt to bring forward a manifoldr applying arithmetic and geometry to

strength has not yet been able to sustain the weight of suchexertion and labor as the almost Herculean task will requirefor its completion. And if my work cannot be finished or pub-lished while I remain alive, I have bequeathed it to that mostlearned and grave man who is the sole relic and ornamentand prop of the mathematical arts among us, D. D. Pedro Nuñes,of Salácia, and not long since prayed him strenuously that, ifthis work of mine should be brought to him after my death,he would kindly and humanely take it under his protectionand use it in every way as if it were his own: that he woulddeign to complete it, finally, correct it, and polish it for the pub-lic use of philosophers as if it were entirely his. And I do notdoubt that he will himself be a party to my wish if his lifeand health remain unimpaired, since he loves me faithfullyand it is inborn in him by nature, and reinforced by will,

and was recently edited by Wayne Shumaker, with an introductory essay by J. L.system of inspection of ‘the true virtues of nature’: in the words of Shumaker, thisa standard scholastic physics and astronomy.’ Dee (1978), ‘Praeface’, p. ix.

B. Almeida / Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 43 (2012) 460–469 461

industry, and habit, to cultivate diligently the arts most neces-sary to a Christian state.2

At first sight, one cannot help but be struck by Dee’s intention toappoint the Portuguese cosmographer and mathematician PedroNunes (1502–1578) as his literary executor in case of prematuredebility. Moreover, Nunes would not only have been the executor,but could have taken Dee’s works as his own. It is significant that ofall of the potential candidates ‘existing’ at the time (including Mer-cator himself), Dee expresses complete confidence in the ability ofhis Iberian friend to make his works available to the public andeven, if needed, carry on his unfinished studies.

This preliminary reading is significant enough to catch inves-tigators’ attention. Yet as far as I can tell, Dee’s biographers havementioned this passage, if at all, merely as a curiosity: for exam-ple, Nunes is not discussed by Fell-Smith (1909), while Woolley(2001) refers to him only briefly.3 In general, other English histo-rians formulate similar notes or do not go much further. For in-stance, in Heilbron’s ‘General notes’ (Dee, 1978, p. 205): ‘Deesubmits his unpublished writings to a literary executor, the math-ematician Pedro Nuñes, for editing if his own life should be cutshort.’ Baldwin (2006), in an article devoted to Dee’s interest innautical science and its applications, includes a brief reference tothe cosmographer’s name and his influence on the Englishman’svision:

Dee’s actions have to be viewed as determined by his own ver-sion of an interdisciplinary, technological and mathematicalvision of the Habsburg Empires. . . . It was a structured systemof quasi-colonial thought developed initially in the Armazénsda Guiné [in Portugal]. . . .The whole notion was brought to itsacademic apogee by his great friend and fellow mathematician,Pedro Nuñez. (Ibid., p. 108)

Since Baldwin’s analysis focuses on Dee’s impact on British naviga-tion rather than Nunes’ (possible) influence, this passage does notprovide further details of their relationship.

Nevertheless, historians like Taylor (1963, 1968, 1971) andWaters (1958), highlighted the link between the two men in theirimportant work on the history of navigation. Taylor, for example,wrote:

John Dee had formed (under circumstances that are quiteunknown) a close friendship with his great Portuguese contem-porary Pedro Nunes, and throughout his career as mathematicaladviser to a long succession of English explorers he is found tobe applying the principles laid down in Nunes’ important worksupon nautical science. Three of Nunes’ books, De Erratis Orontii,De Crepusculis, and De Navigatione were in Dee’s library, and it ispossible that the five-foot Quadrant and ten-foot cross-staff

2 ‘. . .me Scias, praeter periculosissimum, quo toto iam proxime elapso anno laboravi, moplurimum retardavere: viresque etiam meas, nondum posse tantum sustinere studii laborihaud queat opera, vel absolvi, vel emitti, dum ipse sim superstes, Viro illud legavi eruditissimcolumen: nimirum D. D. Petro Nonio Salaciensi: Illumque obnixe nuper oravi, ut, si quandomodisque omnibus, tanquam suo, utatur: absolvere denique, limare. ac ad publicam Philosquin ipse (si per vitam valetudinemque illi erit integrum) voti me faciet compotem: cumgnaviter incumbere, sit illi a natura insitum: voluntate, industria, ususque confirmatum.’Excerpts from this letter, in Portuguese, can be accessed in Costa (1933, p. 233), and Tarri

3 Woolley (2001) includes two brief references to Nunes: ‘Dee also met Pedro Nuñez, thefor a western passage to the Indies. Nuñez evidently became a close and important intelleappointed Nuñez his literary executor’ (p. 20); ‘He [John Dee] arranged for a draft of PropaPedro Nuñez’, (p. 51). There are some mistakes in this appreciation: there is no evidence tsince he was not a navigator but the king’s cosmographer; and Columbus did not set off f

4 A reference to this connection also appears in Johnson & Nurminen (2007); while Krückalso mentions how this relates to Nunes’ and Mercator’s works. Leitão & Almeida (2009) prothe Dee–Nunes connection at http://www.pedronunes.fc.ul.pt/episodes/john_dee/john_dee

5 Some of these questions had already been set in Leitão (2007).

which he describes as in his possession were graduated onthe principle of the Nonnius (Taylor, 1938, p. 8).

Taylor thus highlighted an existing friendship (of which, as faras I know, there is no confirmation from Nunes’ side), and wentfurther by stating that Dee applied some of Nunes’ ideas on nauti-cal science, and suggesting important clues to follow.4 Interest-ingly, however, the connection between Dee and Nunes has notbeen missed in popular culture: Umberto Eco, in his novel Foucault’spendulum, develops a fiction in which Dee plays a significant role in aconspiracy theory referred to as ‘The Plan’, and sets Nunes workingas his cosmographer (Eco, 1989).

Among Portuguese scholars, the connection has been high-lighted by Costa (1933), and the letter was translated into Portu-guese by Rua (2004). Although Rua’s study is more orientedtowards Dee and Nunes’ (possibly) shared astrological interests,the author makes a careful approach to the issue, listing other evi-dence of the links between both men, some of which will be dis-cussed below.

Returning to Dee’s letter, it seems clear that further explanationis needed as to why Dee addresses Nunes as a friend and literaryexecutor. From his words, it is possible to infer common intellectual(and even moral) interests—otherwise why would he trust his worksto the Portuguese, and name him ‘the sole relic and ornament andprop of the mathematical arts’? Dee’s reference to the promotionof ‘the arts most necessary to a Christian state’ may reveal a broaderset of shared interests that deserves a deeper study. Nevertheless, ifone compares the works of both men up to 1558, it is not easy toestablish a connection between them. In his letter, Dee lists workson pure mathematics, astronomy, perspective, cosmography, reli-gion and other topics that may be classified as ‘occult’, but onlyone work on navigation. Hence, it appears that what needs to be clar-ified is more than an influence on nautical science.

The letter raises a number of questions that demand morethoughtful answers. Was the reference in the letter to Mercatoran isolated episode? How far did John Dee’s knowledge of Nunes’scientific work did go? When, why and where did this interestcome about? Indeed, does Dee’s own mathematical programme re-flect Nunes’ ideas in any way? In sum, to what extent was the rela-tionship between both men important in the shaping of Dee’sthought? In this paper I address these questions, review what isknown and provide new evidence for the influence of Pedro Nunes’work on John Dee’s scientific production.5

2. The work of the Portuguese cosmographer

As noted above, the work of Dee and Nunes is not obviouslyconnected, and, judging from his printed works, many of the topics

rbum, alia etiam multa (ab illis, qui. &c.) esse perpessum incommoda, quae mea studiasque onus, quantum illud, Herculeum pene (ut perficiatur) requiret opus. Unde si mea

o, gravissimoque, qui Artium Mathematicarum unicum nobis est relictum et decus eposthumum, ad illum deferetur hoc meum opus, benigne humaniterque sibi adoptet

ophantium utilitatem perpolire, ita dignetur, ac si suum esset maxime. Et non dubitoet me tam amet fideliter, et in artes, Christianae Reip[ublicae] summe necessariasDee (1978, pp. 114–115). The letter is also cited by Van Durme (1959, pp. 36–39)

o (2002, pp. 96–108). For a full Portuguese translation, see Rua (2004).n the leading navigator in Lisbon, from where Columbus had set off in 1492 in searchctual friend. When Dee was struck down with a serious illness in the late 1550s, he

edeumata to be published, and handed over the rest of his literary affairs to his friendhat the two men ever met in person; Nunes was not ‘the leading navigator in Lisbon’rom Lisbon on his first voyage, but from Palos de la Frontera (Huelva, Spain).en (2002) is a website that presents a deep analysis of Dee’s work on rhumb lines andvide an English-language website dedicated to Pedro Nunes, including information on.html.

t,.,.

,

Fig. 1. Difference between a rhumb line or loxodrome (ab) and a great circle (ed),Nunes (2002, p. 113).

462 B. Almeida / Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 43 (2012) 460–469

that attracted Dee did not catch Nunes’ attention. By the time theyoung Dee was in Louvain in the late 1540s, the Portuguese cos-mographer had already published three books, establishing a rep-utation as a fine mathematician throughout Europe.6 Nunes’ firstbook, generally known as the Tratado da sphera, was published in Lis-bon in the end of 1537.7 This consisted of translations into Portu-guese of Sacrobosco’s Tractatus de sphaera, Book I of Ptolemy’sGeography, and the chapters on the sun and moon in Peuerbach’sTeoricae novae planetarum. This edition also included two originaltreatises on theoretical navigation—Tratado que ho doutor Pêro nunezfez sobre certas duuidas de nauegação (‘Treatise made by doctor PedroNunes about certain doubts on navigation’), and Tratado que ho dou-tor pêro nunez Cosmographo del Rey nosso senhor fez em defensam dacarta de marear (‘Treatise made by doctor Pedro Nunes, king’s cos-mographer, defending the nautical chart’). While working as a cos-mographer, Nunes realised that a lack of mathematical knowledgehad resulted in many errors and problems in navigation, and there-fore claimed that seamen should be trained in mathematics. In thesetwo vernacular treatises, he pioneered the use of geometrical andtrigonometrical tools to solve navigation problems. This approachwas uncommon in the ‘art of navigation’ literature of his time, whichpresented mostly straightforward sets of rules, tables, mnemonicsand simple introductions to the Sphere.8

Nunes’ first texts already expressed a clear distinction betweenwhat he later termed ars navigandi and ratio navigandi: the ‘ars’denoting common seamanship based on known sets of rules, proce-dures and instruments, and the ‘ratio’ referring to nautical activitybased in the understanding and use of mathematical principles,eventually leading to something similar to what could be called to-day a ‘scientific seamanship’ (Leitão, 2006, pp. 188–189). In the pro-cess, Nunes also presented a thorough study of the nautical chart,identifying its problems, and was the first to develop the conceptof a rhumb line, known today as the loxodromic curve (Fig. 1).9

6 Gemma, Mercator and Dee were among the first to study and apply some of Nunes’ ideatransmission of Nunes’ works and ideas (considering texts in vernacular) on navigation inmore on the European diffusion of Nunes’ work see Leitão (2002) and (2007).

7 First edition, Nunes (1537). The latest edition is Nunes (2002).8 Three known examples are Faleiro (1535), Medina (1545) and Cortés (1551).9 The word ‘loxodrome’ was introduced by Willebroord Snell; see Snell (1624).

10 First edition, Nunes (1542). The latest edition is Nunes (2003).11 As Nunes states in his dedication to the King: ‘I was persuaded to clearly explain thi

mathematics. So, meditating and investigating, I have discovered things that I have read notranslation from Portuguese is mine; see Nunes (2003, p. 142).

12 First edition: Nunes (1546). See the latest edition, Nunes (2005).13 First edition: Nunes (1566). See the latest edition, Nunes (2008).14 First edition: Nunes (1567). See the latest edition, Nunes (2010).15 The ‘Nunes program’ is presented and discussed in Leitão (2006).16 This text was very influential at the time. For example, Henri de Monantheuil (1599)

However, Nunes did not confine his work to nautical science. In1542 he published De crepusculis, in which he answered a questionposed by a noble pupil about the problem concerning the length oftwilights for different regions, and showed how an atmosphericphenomenon could be explained using a deductive Euclideanstructure.10 As in his previous book, he based his mathematicalexplanations on real questions made by real people, expressing hisconcern to reconcile mathematics with physical reality.11 Through-out the book, he also presented a great deal of relevant informationfor astronomers, including an interesting suggestion for a graphicalsolution destined to improve instrumental measures, known todayas the nonius scale. Nunes’ valuable suggestions later led to this bookbeing highly regarded by, among others, Christopher Clavius (1538–1612) and Tycho Brahe (1546–1601). In the dedication to the King,Nunes also announced his intention to complete a translation ofVitruvius’ De architectura, while in the final pages he announced sev-eral works to be published in the future. These included treatises onthe astrolabe, proportions or globes and nautical charts, establishinghim as an interesting author, worthy of notice by the internationalscholarly community.

In 1546, Nunes published the book that would establish his sci-entific reputation as one of the leading European mathematicians.De erratis Orontii Finaei12 revealed errors in the mathematical dem-onstrations of Oronce Fine (1494–1555), the famous and highly re-garded professor of mathematics at the Collège de France, who hadtried to solve three classical problems (to double a cube, to trisectan arbitrary angle, and to square a circle) as well as some gnomonicproblems. After this, Nunes published twice more. In 1566 he pub-lished his Opera, which included his most advanced ideas on differ-ent aspects of navigation, astronomy, mechanics, and other topics,with a major printer in Basel.13 In 1567, the Libro de Algebra ap-peared in Antwerp.14 These two titles concluded the mathematicalwork that Nunes had started to develop in the early 1530s as anexpression of his scientific thought and of his ‘program for the math-ematization of the real world.’15 As claimed above, this programmeis most apparent in the case of nautical science, since its main pur-pose was to achieve a full practice of seamanship ‘by art and by rea-son’, in such a way that it would be possible to merge the study andpractice of mathematics with the natural skills and craftsmanship ofseamen. However, the programme also extended to astronomy andmechanics. The topic of the minimum twilight was mentioned ear-lier, but Nunes also confronted peripatetic mechanics in a mathe-matical explanation of the movement of a rowing boat in a textincluded in his Opera (Annotationes in Aristotelis Problema Mechani-cum de Motu nauigij ex remis).16

3. New evidence

John Dee is now viewed as one of the most interesting person-alities of the Elizabethan intellectual world. Within the social con-text of his time, he developed a national and international network

s, but are far from being the only ones. In my Ph.D. research I address the influence andthe sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, mainly in Portugal, Spain and England. For

s matter [i.e. twilights] with help of the most certain and most evident principles ofwhere else and would not be worth of credit, had they not been demonstrated . . . ’ The

and Giuseppe Biancani (1615) included important comments on it.

Fig. 2. Left: Frontispiece of John Dee’s copy of de Sá’s De navigatione. It is possible to read ‘Joannes Deeus: 1552:’ in the centre of the page. Right: highlight of the last page withan early depiction of Dee’s monas hieroglyphica inserted into a human representation. By permission of Cambridge University Library.

B. Almeida / Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 43 (2012) 460–469 463

of contacts, extending from the Court to the university and to otherinstitutions that promoted the sharing of knowledge about the sci-ences. He collaborated with the Muscovy Company, and his train-ees and collaborators included John Davis, Richard Hakluyt, WalterRaleigh, Francis Drake, Thomas Digges, Thomas Harriot and others.At the international level, he established personal and scientificcontacts with many learned men of his time, including GirolamoCardano, Oronce Finé, Federico Commandino, Abraham Ortelius,Gemma Frisius and Gerard Mercator. Considering his own writtenindications in the aforementioned letter, the Portuguese PedroNunes may well be included in this list.

It is not clear when Dee’s interest for Nunes’ work first cameabout. While a young man, he studied at Cambridge Universityand, in his pursuit of knowledge, later headed to mainland Europein 1547. The period spent in Louvain was significant in shaping hisearly natural philosophical ideas. In fact, it was during his stay inthe Low Countries, first in 1547 and then later between 1548 and1550, that the young Dee must have first heard of Nunes’ work.It is reasonable to speculate that Nunes’ writings would havereached Louvain—the city where Gemma Frisius (1508–1555)had gathered a group to whom he taught private lessons on geom-etry and astronomy17—without difficulty. The region had strongcommercial connections with Portugal, and there was also a largecommunity of Portuguese Jews. One of these, Diogo Pires (or DidacusPyrrhus Lusitanus), had links to Portuguese intellectuals at Louvain,such as Amato Lusitano and Damião de Góis. He also wrote a dedica-tory poem included in Gemma’s 1540 edition of Apian’s Cosmogra-phy. In the absence of direct evidence, it is not possible toestablish a stronger correlation between Nunes, Gemma and Pires,but it is interesting to note that Pires also studied at Louvain, andthat he was a friend of the publisher Rutger Ressen (Rutgerus Res-cius), himself a friend of Gemma.18 There is little doubt that Gemma

17 ‘[I]l [Gemma Frisius] donnait depuis 1543 et au moins jusqu’en 1547, à son domicfréquentées notamment par Gérard Mercator, l’Espagnol Juan de Rojas, l’Anglais John Dee

18 Diogo Pires (1517–1599) studied medicine in the University of Salamanca, the same pbecame a well known poet. For more on Pires, see António Manuel Lopes Andrade (2005)

19 Mercator knew most of Nunes’ work, possessing both printed and manuscript copies20 In Roberts & Watson (1990): De erratis Orontii Finaei (entry 100), Petri Nonii Salaciensi21 De Sá (1549). Dee’s copy of this book is today at Cambridge University Library, shelfm22 Dee’s signs his name in Latin and writes ‘1552’, but it is possible that he knew the bo

and Gerard Mercator (1512–1594) would have paid attention toNunes’ writings.19 Mercator made a globe picturing rhumb lines in1541, and in 1545 Gemma included a description of a rhumb linein his edition of Apian’s Cosmography (Apian, 1545, Ch. XV, fols.23v–25v).

In 1550/1, John Dee was in Paris, where he met Oronce Finé. It isvery likely that Dee became aware of Nunes’ book on the French-man’s mathematical errors during this period. Even without directevidence for this (other than noting that he later had a copy of thisbook at Mortlake), we might speculate that a reading of this textinfluenced his interest on the unresolved problems of squaring ofthe circle and doubling the cube, and even further work on Euclid’sElements.

Dee owned copies of all of Nunes’ books, with one exception:the Tratado da sphera.20 The reason for his failure to acquire thisbook, aside from its linguistic relevance, may relate to a clue recentlyfound at Cambridge University Library. Clulee (1977, p. 640, n. 27)mentions the existence of a book on navigation in Dee’s library, to-gether with the date 1552. Possible candidates are few in number,and it is highly likely that either the work referred to is either Portu-guese or Spanish. It is here worth noting that the catalogue of Dee’slibrary in Roberts and Watson (1990) includes Diogo de Sá’s De nau-igatione (Paris, 1549), which is actually one of the most aggressiveattacks on Nunes’ ideas.21 Dee acquired his copy of this work—nowat Cambridge University Library—in 1552, after his return to Eng-land, and devoted a good deal of study to it (Fig. 2).22

Despite its allusive title, this work covers much more than nav-igation. It is composed of three books: in the first, the author opensa discussion concerning the certainty of mathematics and its effi-cacy in producing true knowledge. The subject had an ontologicalnature, for it was claimed that mathematics dealt only with acci-dents of substances, rather than with substances themselves, thus

ile, des leçons privées qui portaient sur la géométrie et l’astronomie. Elles étaientet le Frison Sixtus ab Hemminga.’ Hallyn (2008), p. 16.

lace where Nunes had studied years before. He did not finish his medical studies but.of his books in his personal library. See Cherton & Watelet (1994).s Opera (entry 189), De crepusculis (entry 674), Libro de algebra (entry 769).ark R⁄.5.27 (F). See note [B 154] in Roberts & Watson (1990).

ok earlier than this, while in Paris, since it was published there.

Fig. 3. De nauigatione, fols. 17v and 18r. By permission of Cambridge University Library.

464 B. Almeida / Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 43 (2012) 460–469

producing a rather ‘incomplete’ knowledge of nature.23 Accord-ingly, de Sá also discusses the classification and hierarchy of sci-ences. In the second book, he explicitly attacks Nunes’ treatises bymeans of a dialectic dispute between the philosopher and the math-ematician, in which the first repeatedly exposes the limitations andsuperficiality of mathematics from a philosophical point of view. DeSá was a scholar of humanist and scholastic training, who claimedthat true and certain knowledge, as sustained by Aristotle in his Pos-terior analytics, was obtainable only by means of the philosophicalstudy of nature, rather than through mathematical study. In the thirdbook, de Sá continues his critiques while suggesting some solutionsto simple nautical issues, such as the sun’s regiment.24

The reading of this work indicates that de Sá did not object tothe use of mathematics in some cases, although for him mathemat-ics dealt only with formal causes and therefore produced a ‘limited’knowledge of reality. This was not a novel intellectual position, gi-ven that this discussion was very much alive in sixteenth centuryEurope (and is today known as the quaestio de certitudine mathem-aticarum).25 Mota suggests that de Sá was well aware of the discus-sion taking place in Paris, and played an important role in exportingit to Portugal (2008, p. 176). In my opinion, De nauigatione is moreinteresting in what it attacks than in what it proposes. The authoranalyses Nunes’ first treaty step by step according to his own agenda,and launches an all round assault on what he perceived to be thecosmographer’s programme: the use of mathematics as a basis forall certain knowledge about nature, and the mathematization of sci-entific subjects. Yet Nunes never directly alluded to the quaestio inhis works, although he argued that the strength of mathematicslay in its demonstrations and on the logical progression that permit-ted it to explain natural phenomena.

However, it may be argued that de Sá’s attack also backfired,since the second and third books included fine translations of

23 ‘Mathematica non sunt substantia rerum, sed accidentia superuenientia substantiis’, d24 For more on Nunes and de Sá dispute see, for example, Albuquerque (2002).25 On the quaestio in Portugal and the role of Diogo de Sá’s book in this discussion, see M

much of Nunes’ early work, thus providing Latin versions thatcould be read by any interested European scholars who were un-able to read Portuguese. John Dee acquired the book in 1552, andtherefore was an early reader of de Sá’s ideas. His copy and hisannotations (mainly underlining, short marginal comments, mar-ginal pointers and manicules) reveal more about his interests inthe text. In Book One he was above all interested in the discussionconcerning the certainty and application of mathematics, and onthe hierarchy of sciences (Fig. 3). Throughout, de Sá demonstratesthat he knows the basic sources for the discussion on the quaestiovery well and, from his underlining, it seems that Dee also bene-fited from this.

In Book Two, Dee continues to reveal his interest in the hierar-chy of the sciences and in the mathematical principles of nauticalscience. On fol. 23r, he appears to suddenly lose interest as de Sábrings theological arguments into the discussion, only to assumeinterest again at fol. 28v, when de Sá turns to cabala, Pico dellaMirandola and astrology (Fig. 4). On fol. 30r (when de Sá reiteratesthe theological arguments), Dee once more stops underlining andonly starts again when the author begins his translation of Nunes’work. Dee then concentrates on technical aspects of the theory ofrhumb lines. In Book Three, he again shows interest in more tech-nical aspects (of cartography, for example), paying close attentionto the discourse of the ‘mathematician’ (that is, Nunes’ words andideas translated and adapted by de Sá) and showing virtually nointerest in the practical applications proposed by Diogo de Sá.

For instance, Fig. 5 provides a good example of Dee’s study of deSá’s partial translation of Nunes’ first treatise (Nunes, 2002, pp.114–115). De Sá’s diagram is also adapted from the same first trea-tise (ibid., p. 115). At the top right corner, Dee’s note, ‘Nonnius’,calls attention to an important selection of the cosmographer’s the-ory of rhumb lines.

e Sá (1549), fol. 13r.

ota (2011).

Fig. 4. De nauigatione, fols. 28v–29r (the circle around Pico’s name is mine). By permission of Cambridge University Library.

Fig. 5. De nauigatione, fols. 83v–84r. By permission of Cambridge University Library.

B. Almeida / Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 43 (2012) 460–469 465

In conclusion, it seems that Dee was interested in the power ofmathematics to construct valid knowledge, and in Nunes’ articula-tion of this subject within his texts on nautical science. Even ifembedded within a philosophical discussion, the correct transla-tion and adaptation of Nunes’ treatises seems to have enabled

26 Namely Faleiro (1535), Medina (1545) and Cortés (1551).

Dee to use these works as a textbook on the topic. In fact, in1552 only three other significant treatises on navigation wereprinted, none of which were available in the English language.26

The mathematical content of those treatises was also very elemen-tary. Nonetheless, in addition to the more advanced material on

Fig. 6. Nunes’ first representation of a rhumb line (left: the centre is a pole, the outer circle is the equinoctial, the red line is a rhumb line) compared with a modernrepresentation of a ‘Paradoxal Compass’ (right: image from Krücken, 2002, with permission). Examples of rhumb lines are given in red (note: the two diagrams are not for thesame rhumb). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

466 B. Almeida / Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 43 (2012) 460–469

Nunes’ ideas, de Sá’s text also included some basic notions onnavigation that could be useful. The acquisition of De nauigationemay also echo Dee’s interest in the certitudine mathematicarumwhile he was still in Paris, and his interest in the classificationof sciences, as later seen in his Mathematicall preface to Euclid(Dee, 1570).

4. Enter rhumb lines

All this considered, one can speculate that the reading of Denauigatione was a decisive factor in Dee’s decision to contact Nun-es. Unfortunately, it is not possible to confirm the existence of anepistolary correspondence since the Portuguese cosmographernever alluded to it. This is not an unusual situation, since Nunesnever refers to any of his mathematical contacts, but, if such a cor-respondence existed, we might expect that a much discussedmathematical topic of the time—the construction of rhumb ta-bles—was not left out of these discussions.

Nunes was the first to write about rhumb lines, but his firsttreatises did not provide a method for calculating rhumb tables.In 1541, and without indicating a mathematical process for doingit, Mercator devised a globe representing rhumb lines. By this time,Nunes was already developing his mathematical theory of rhumblines and was aware of the need to calculate tables to use in navi-gation, although it is not known if he already had devised a goodmathematical method for doing so. What is known is his involve-ment in another polemic against a scholar who had proposed an

27 Until now was not possible to identify either the scholar’s identity or his text attackinwith a manuscript defence. This document is presently kept at the Biblioteca Nazionalemanuscript, see de Carvalho (1953). See also Almeida (2006) for a more technical study o

28 This manuscript can be found in Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Ashmole 242, No. 43. It hDee called ‘paradoxal navigation’, a subject later also addressed by John Davis and others. Seand Davis certainly owed much of it to the documents taken from Dee’s library.

29 Taylor (1968, p. 95). For more on this subject see Krücken (2002).30 Wright (1599). According to Waters (1958, pp. 372–373), Dee probably discussed the

independent solution to Mercator’s projection. Nevertheless, there is a similarity betweensuggests that Wright’s Certaine errors in navigation may have benefited from these contac

alternative (and incorrect) description of the rhumb line, andwho had tried to calculate rhumb tables. This episode shows thatthe discussion was alive in Portugal in the 1540s.27 Only in 1566would Nunes present a mathematical method for calculating rhumbtables.

Between 1556 and 1558, John Dee was interested in resolvingthe cartographic problems introduced by the navigation in highlatitudes, and calculated a set of tables known as Canon gubernau-ticus or an arithmeticall resolution of the paradoxall compas.28 In E. G.R. Taylor’s opinion, this Canon,

was in fact a practical development on the teaching of PedroNuñez on this subject and its invention belongs to a periodwhen Dee is known to have been in personal touch with thegreat Portuguese.29

From the tables was possible to draw rhumb lines, or ‘paradoxal’lines, on a ‘Paradoxal compass’ which Taylor defined as a zenithalequidistant projection chart. In his Canon gubernauticus, Dee calcu-lates the latitude and longitude for the seven classical rhumbs spi-ralling across the globe from a point at the equator to a point at 80�latitude, resembling Nunes’ own images (Fig. 6).

Early stages of the development of the calculus of rhumb linesimplied the resolution of series of spherical triangles, used by bothNunes and Dee. Dee’s method added technical nuances to that firstpublished by Nunes in 1566, although, interestingly, it was similarto the one Edward Wright published in 1599.30 This coincidenceraises some questions about the ‘debate’ over rhumb lines between

g Nunes’ ideas on rhumb lines. However, the cosmographer responded to this attackdi Firenze (Codice palatino no. 825). For a modern transcription and study on this

f the development of rhumb lines in Nunes’ work.as no date and includes many rectified values. These tables were in fact aids to whate, for example, Davis (1595), fol. K2v. The definition provided suggests a superficial study,

se tables and the nautical triangle solution with Thomas Harriot, who developed anDee’s and Wright’s tables suggesting the usage of the same calculus method. It also

ts.

B. Almeida / Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 43 (2012) 460–469 467

Dee, Mercator and Nunes. First, it questions the outline of this ashared knowledge, a challenge supported by the lack of documen-tary evidence; second, if there was a debate, it must be assumed thatthe Englishman and the Portuguese diverged in their methods forcalculating rhumb lines. In effect, Nunes’ method did not have muchinfluence in England, where Wright’s and Harriot’s would eventuallysucceed. Nevertheless, I would suggest that only knowledge of Nun-es’ ideas permitted the advances made by those men. In fact, none ofthem omitted to give the cosmographer some credit for thesedevelopments.31

With or without an epistolary connection, John Dee would intime express his own vision of the nautical science in his Mathe-maticall preface to Euclid:

The Arte of Nauigation, demonstrateth how, by the shortestgood way, by the aptest Directio[n], and in the shortest time,a sufficient Ship, betwene any two places (in passage Nauiga-ble,) assigned: may be co[n]ducted: and in all storms, & naturaldisturbances chauncyng, how, to vse the best possible meanes,whereby to recouer the place first assigned. What nede, theMaster Pilote, hath of other Artes, here before recited, it is easieto know: as, of Hydrographie, Astronomie, Astrologie, and Horo-metrie. Presupposing continually, the common Base, and foun-dacion of all: namely Arithmetike and Geometrie. So that, he behable to vnderstand, and Iudge his own necessary Instrumentes,and furniture Necessary: Whether they be perfectly made or no:and also can, (if nede be) make them, hym selfe. . . .And also, behable to Calculate the Planetes places for all tymes . . . .

Sufficiently, for my present purpose, it doth appeare, by the pre-misses, how Mathematicall, the Arte of Nauigation, is: and how itnedeth and also vseth other Mathematicall Artes.32

In Dee’s opinion, the ‘modern’ sea pilot should base his every-day art on knowledge supported by mathematical methods andtools. This intellectual position coincides with Nunes’ own visionof the ratio nauigandi, reinforced in his 1566 work:

Everything that we write on these [nautical] subjects must bereceived without any hesitation, since nothing exists moreexact, nothing more certain and nothing more evident thenmathematical demonstration, which certainly nobody will everbe able to oppose.33

In fact, the ideas that both men shared would echo throughoutEurope and were included in many sixteenth- and seventeenth-century navigation textbooks.34 Dee’s role in the reception, appro-priation, diffusion and transmission of these ideas has to be under-lined: in England (and, indeed, in Europe) he was one of the firstto consider navigation as a mathematical discipline. This intellectualposition reinforces his important role in what both Waters and Tay-lor called ‘the English awakening’ to maritime affairs.

31 For example, when Wright introduces the errors associated with common nautical chaMartine Cortese . . .but specially by Petrus Nonius in his second book of Geometrical observathe world seemed to correct them, by making the distances of the parallels . . .yet none of thfol. C2v.

32 Dee (1570), sigs. d.iiij.v–A.j.r. The English Elements was of great importance for the Englother work in the English tongue has been so influential in stimulating the growth in Eapplication of mathematics to the daily problems of life . . . ’, Waters (1958, p. 131).

33 My translation. The original text is in Nunes (2008, p. 30).34 It is possible to trace Nunes’ ideas and influence in works by some of the most importa

examples of printed vernacular books: in Spain, Céspedes (1606); in the Low Countries, C35 See Dee (1851 [1592]) and (1599). In the 1599 letter, Dee lists De Triangulorum recti

conscripti-Anno-1560.36 He states this in the dedication to Cardinal Henrique. See Nunes (2010, p. 8).37 Dee (1998, p. 165). Jakob Kurtz also discussed improvements to the ‘nonius scale’ with

Clavius attended Nunes’ classes at that university. Nevertheless, he had a good knowlemathematicians of his time. On Clavius’ contacts with Kurtz, see Clavius (1992, p. 64).

38 Taylor (1954, p. 314), notes that William Thomas suggested the translation of classicalThe sphere of Sacrobosco. Dedicated to The high and mightie Prince Harry, Duke of Suffolk, in

5. A wider influence?

While it is clear that Nunes influenced Dee’s vision of nauticalscience, this connection still does not explain why Dee consid-ered the Portuguese to be ‘the sole relic and ornament and propof the mathematical arts among us.’ In fact, much less has beensaid by historians about Nunes’ influence on Dee’s use of math-ematics to study nature and on his mathematical views ingeneral.

Besides the already noted convergence of the role and use ofmathematics, a few other clues are worth mentioning. The first isDee’s dedication of mathematical works. In his Compendious re-hearsal (1592), and again in a letter to the Archbishop of Canter-bury (1599), he claims to have completed a work in 1560 on theareas of plane triangles—De Triangulorum rectilineorum Areis35—dedicated to the ‘excellentissimum Mathematicum’, Pedro Nunes.In his essay in this volume, Stephen Johnston establishes an interest-ing connection between this work on triangle areas and another lostwork, named Tyrocinium mathematicum, also dedicated to Nunes(Johnston, 2011). These dedications may point to a broader recogni-tion of the Portuguese cosmographer’s mathematical work, perhapseven to a quest for some kind of ‘intellectual patronage.’ They mayalso indicate a shared interest in specific mathematical topics. A pos-sible connection could be found with Nunes’ Libro de algebra. Thisbook was only published in 1567, but Nunes began work on it aboutthirty years earlier.36 In this book, he studied the areas of severalgeometric figures, including plane triangles. If we assume that acommon interest existed, we may also speculate that the English-man already knew of Nunes’ algebraic texts, and worked on similarsubjects.

Furthermore, in 1584 Dee noted that he and Jacob Kurtz hadexamined instruments containing improvements (the noniusscale) also proposed by the Portuguese cosmographer:

After dinner I went to Dr. Curtz home. . . .he showed divers hislabours and inventions mathematical, and chiefly arithmeticaltables, both for his invention by squares to have the minuteand second of observations astronomical and so for the mend-ing of Nonnius his invention of the quadrant dividing in 90,91, 92, 93, etc.37

In the Mathematicall praeface, Dee tried to justify and promotethe translation of Euclid’s Elements into the vernacular,giving several examples of similar translation projects under-taken abroad.38 These included an example from the IberianPeninsula:

Nor yet the Vniuersities of Spaine, or Portugall, thinke their rep-utation to be decayed: or suppose any their Studies to be hin-dred by the Excellent P. Nonnius, his Mathematicall workes, invulgare speche by him put forth (Dee, 1570, sig. A.iiij.r).

rts he states: ‘These errors . . .have been much complained of by diverse, as namely bytions, rules, and instruments: And although Gerardus Mercator in his universal Map ofem taught any certain way how to amend such gross faults . . . ’, Edward Wright (1599),

ish mathematical arts in the sixteenth century. In David Waters’ opinion: ‘Probably nongland of mathematics, navigation, and hydrography, and in leading to the general

nt actors of European nautical science of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Asoignet (1581); in France, Fournier (1643); in England, Wright (1599).lineorum Areis-libri-3-demonstrati: ad excellentissimum Mathematicum Petrum Nonium

Cristopher Clavius, a former student at Coimbra. It is not certain whether, as a student,dge of the cosmographer’s works and also considered him to be one of the best

texts into English in the mid-1540s. He even left a translation of Sacrobosco’s Sphere:London, British Library MS Egerton 837.

468 B. Almeida / Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 43 (2012) 460–469

This significant remark shows that Dee was aware of the cos-mographer’s vernacular writings and that he was also familiar withthe translation of his works and agreed with the principles behindthis.39 At the time, the use of vernaculars for natural philosophicaldiscourse was being widely defended throughout Europe. Nuneswas also involved in such defences, having clear opinions aboutthe value of translated works. In his 1537 book, he had stated:

Science has no language, so it is possible to explain it by usingany language. . . .And if, therefore, one can translate any non sci-entific text from one language to other, I do not know where, somuch fear to put a science text in common language, comesfrom.40

Unfortunately, these sources cannot support more detailed con-clusions, and we can only hope that future sources and studies mayshed more light on this interesting connection.

6. Final remarks

My intention in this paper has been to focus on the John Dee–Pedro Nunes connection, a subject typically not addressed by Deescholars. First, I have aimed to strengthen the idea that the Portu-guese cosmographer had an influence on Dee’s nautical interests.Second, by examining both new and previously known evidence,I suggest that a wider influence can be established, and that bothmen shared comparable scientific programmes.

One important conclusion of this study is that John Dee was thefirst and most important vector of transmission and diffusion ofthe Portuguese cosmographer’s work on navigation in sixteenth-century England.41 In fact, Nunes’ mathematical approach to naviga-tion had an impact on the young Dee while he was developing hisearly studies and establishing contacts with prominent men of sci-ence with similar interests. As William Sherman observes, ‘Thesemen [that is, Frisius, Mercator, Ortelius and Nunes] exercised aninfluence on Dee that extended far beyond the classroom and longpast his visit to Louvain’ (Sherman, 1995, p. 5). Naturally, Dee endedup developing his own programme which, in its first stage, wasbased on the use of mathematical principles as tools to describethe natural world, something that he would later promote in his roleas a consultant on nautical subjects, and continue to practicethroughout his life.

In this paper, I have not focused on the technical details thatDee transmitted to his collaborators while advising on nauticalsubjects. These remain a subject for further investigation.42 It isHeilbron’s opinion that,

Dee’s contributions were promotional and pedagogical: headvertised the uses and beauties of mathematics, collectedbooks and manuscripts, and assisted in saving and circulatingancient texts; he attempted to interest and instruct artisans,mechanics, and navigators, and strove to ease the beginner’sentry into arithmetic and geometry. It is in this last role, as ped-agogue, that Dee displayed his competence, and made his occa-sional small contributions (which he classed as great andoriginal discoveries) to the study of mathematics as a consul-tant on nautical subjects (Dee, 1978, p. 17).

39 Besides having published his first work in Portuguese, Nunes would also publish his lasworking on a translation of Vitruvius’ De architectura.

40 ‘ . . .a sciencia não tem lingoagem: e que per qualquer que seja se pode dar a entender .

sciencia sem se estranhar: nam sey entender donde veo tamanho receo de treladar na linguEnglish is mine.

41 That is, prior to Wright’s Certaine erros in navigation (1599). A more detailed study of thAlmeida (2011).

42 Taylor leaves some clues when addressing the nautical instructions to Frobisher and topractical application; see Taylor (1954, p. 35). Several manuscripts at the British Library s

While agreeing with these words insofar as they concern Dee’scontribution to pure mathematics, I would stress that Dee was alsoup to date with many of the mathematical developments of histime, and that he worked alongside some of the most influentialmathematical practitioners in Elizabethan England. He would ulti-mately outline his own mathematical programme in the Mathe-maticall preface, which Frances Yates considered, in a broadsense, ‘the manifesto of Dee’s movement’ (1979, p. 94). The wordsof Peter French echo this claim:

The essential point to be remembered about Dee’s preface isthat it is a revolutionary manifesto calling for the recognitionof mathematics as a key to all knowledge and advocating broadapplication of mathematical principles (French, 1972, p. 167).

Another inference to take from this study, and from French’s words,is that, even while recognising Dee as an important figure withinthe Elizabethan sciences, this ‘revolutionary manifesto’, as Frenchcalled it, was deeply influenced by other authorities—such as PedroNunes—who were involved in a broad movement concerned withthe legitimation of mathematics. It therefore helps us to situateDee’s writing within this context. While Nunes was particularlyinfluential in shaping the English polymath’s ideas on nautical sci-ence, I have argued that he also contributed more generally to Dee’sbroader vision of the sciences. I therefore suggest that in the histor-iography of John Dee, Pedro Nunes’ contribution deserves morethan a brief reference to the presence of his name in Dee’s letterof 1558.

Acknowledgements

This research was made possible by a PhD scholarship fromFundação para a Ci~encia e a Tecnologia (reference SFRH/BD/22952/2005). I also have to thank the support by Centro Interuni-versitário de História da Ci~encia e da Tecnologia, at Lisbon Univer-sity. I am most of all grateful to Henrique Leitão for his constanthelp with this paper and for his ever valuable recommendations.I am also deeply grateful to Ana Almeida for revising this text. Iwould like to thank Samuel Guessner for inspiring discussions,and António Lopes Andrade for helpful suggestions. I cannot forgetJennifer Rampling and her commitment, work and motivationwhile organizing the John Dee Quatercentenary Conference andfor the honour of being invited to participate. I also thank KatieTaylor for her kind help. I thank all the participants for their com-ments and for all that I learned while attending the conference,particularly Stephen Johnson for his helpful insights and for the pa-per he presented at the conference, which was of great encourage-ment to my own work. Finally, I thank the staff of the Rare Booksroom at Cambridge University Library.

References

António Manuel Lopes Andrade, A. (2005). O Cato Minor de Diogo Pires e a poesiadidáctica do século XVI. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation. Universidade de Aveiro.

Albuquerque, L. (2002). Pedro Nunes e Diogo de Sá. In J. Carvalho e Silva (Ed.),Antologia de textos essenciais sobre a história da matemática em Portugal(pp. 183–207). Lisboa: Sociedade Portuguesa de Matemática.

Almeida, B. (2006). A curva loxodrómica de Pedro Nunes. In M. V. Maroto & M. E.Piñeiro (Eds.), La ciencia y el mar (pp. 149–181). Valladolid: Los autores.

t work Libro de Algebra in Spanish. Also, in De crepusculis Nunes announced that he was

. .E pois de huma lingoagem em outra se pode tirar qualquer scriptura que não seja deagem vulgar outra qualquer obra de sciencia . . . ’ Nunes (2002, p. 5). The translation to

e impact of Nunes’ works on navigation in England will be available in my Ph.D. thesis:

his master navigator Christopher Hall. She also claimed that these instructions had nohould also be carefully studied with that in mind, for instance MS Harley 167.

B. Almeida / Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 43 (2012) 460–469 469

Almeida, B. (2011). Sobre a influência da obra de Pedro Nunes na náutica dosséculos XVI e XVII: Um estudo de transmissão de conhecimento. UnpublishedPh.D. dissertation. Universidade de Lisboa.

Apian, P. (1545). Cosmographia Petri Apiani, per Gemmam Frisium apud Louaniensesmedicum & mathematicu[m] insignem, iam demum ab omnibus vindicata mendis,ac nonnullis quoq[ue] locis aucta, additis eiusdem argumenti libellis ipsius GemmaeFrisii. Antwerp: sub scuto Basiliensi, Gregorio Bontio.

Baldwin, R. (2006). John Dee’s interest in the application of nautical science,mathematics and law to English naval affairs. In S. Clucas (Ed.), John Dee:Interdisciplinary studies in English Renaissance thought (pp. 97–130). Dordrecht:Springer.

Biancani, G. (1615). Aristotelis loca mathematica ex vniuersis ipsius operibus collecta, &explicata: Aristotelicae videlicet expositionis complementum hactenus desideratum:Accessere De natura mathematicarum scientarium tractatio: atq; Clarorummathematicorum chronologia. Bologna: Bartholomaeum Cochium.

Biblioteca Nazionale di Firenze. Codice palatino no. 825. Firenze.British Library, MS Harley 167. London.de Carvalho, J. (1953). Uma obra desconhecida e inédita de Pedro Nunes: [defensão

do tratado de rumação do globo para a arte de navegar]. Revista da Universidadede Coimbra, 17, 521–631.

de Céspedes, A. G. (1606). Regimiento de navegacion. Madrid: Juan de la Cuesta.Cherton, A., & Watelet, M. (1994). Catalogus. In M. Watelet (Ed.), Gérard Mercator

cosmographe (pp. 403–413). Brussels: Fonds Mercator de la Banque Paribas.Clavius, C. (1992). Corrispondenza (7 vols.) (Vol. II, Part 2, p. 64). Pisa: Universite di

Pisa, Dipartimento di Matematica.Clulee, N. H. (1977). Astrology, magic, and optics: Facets of John Dee’s early natural

philosophy. Renaissance Quarterly, 30, 632–680.Coignet, M. (1581). Instruction nouvelle des poincts plus excellens & necessaires

touchant l’art de naviguer. Anvers: Henry Hendrix.Cortés, M. (1551). Breve compendio de la sphera y de arte de navegar, con nuevos

instrumentos e reglas, ejemplificado con muy subtiles demonstraciones: Compuestopor Martin Cortes natural de burjalaroz en el reyno de Aragon y de presente vezinode la ciudad de Cadiz: Dirigido al invictissimo Monarcha Carlo Quinto Rey de lasespañas etc. Señor Nuestro. Seville: Antón Alvarez.

Costa, A. F. (1983). A Marinharia dos Descobrimentos (4th ed.). Lisboa: EdiçõesCulturais da Marinha (First published 1933).

Davis, J. (1595). Seaman’s secret. Devided into 2. partes, wherein is taught the threekindes of sayling, horizontall, paradoxall, and sayling upon a great circle: Also anhorizontall tyde table for the easie finding of the ebbing and flowing of the tydes,with a regiment newly calculated for the finding of the declination of the sunne, andmany other most necessary rules and Instruments, not heeretofore set foorth by any.London: Thomas Dawson.

Dee, J. (1558). Canon gubernauticus. Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Ashmole 242, No.43.

Dee, J. (1599). A letter, containing a most briefe discourse apologeticall, with a plainedemonstration, and feruent protestation, for the lawfull, sincere, very faithfull andChristian course, of the philosophicall studies and exercises, of a certain studiousgentleman: An ancient seruant to her most excellent Maiesty Royall. London: PeterShort.

Dee, J. (1851). The compendious rehearsall of John Dee. In J. Crossley (Ed.),Autobiographical tracts (pp. 1–45). Remains historical and literary of Lancaster andChester Counties (Vol. 1). Manchester: The Chetham Society. (Original, 1592).

Dee, J. (1978). John Dee on astronomy: ‘‘Propaedeumata aphoristica’’ (1558 and 1568),Latin and English (W. Shumaker, Trans., J. Heilbron, Intro.). Berkeley, CA:University of California Press.

Dee, J. (1998). The diaries of John Dee (E. Fenton, Ed.). Charlbury, Oxon.: Day Books.Eco, U. (1989). O pêndulo de Foucault. Lisboa: Difel. (Translation of Il pendolo di

Foucault. Milano: Bompiani, 1988).Euclid (1570). The elements of geometry of Euclid of Megara (H. Billingsley, Trans.).

London: John Daye.Faleiro, F. (1535). Tratado del Esphera y del arte de marear: Con el regimiento de las

alturas: Con algunas reglas nuevamente escritas muy necessarias. Sevilla: JuanComberger.

Fell-Smith, C. (1909). John Dee. 1527–1608. London: Constable & Company.Fournier, G. (1643). Hydrographie contenant la théorie et la practique de toutes les

parties de la navigation/composé par le Pere Georges Fournier. Paris: Michel Soly.French, P. (1972). John Dee: The world of an Elizabethan magus. London: Routledge.Hallyn, F. (2008). Gemma Frisius, arpenteur de la terre et du ciel. Paris: Éditions

Champion.Johnson, D. S., & Nurminen, J. (2007). History of seafaring. Navigating the worlds

oceans. London: Conway Maritime Press; Juha Nurminen Foundation.Johnston, S. (2011). John Dee on geometry: Texts, teaching and the Euclidean

tradition. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A, this volume.doi:10.1016/j.shpsa.2011.12.005.

Krücken, W. (2002). Interpretation und Rekonstruktion des ‘‘Paradoxall compasse’’.http://www.wilhelmkruecken.de. Accessed 15.12.10.

Leitão, H. (2002). Sobre a difusão europeia da obra de Pedro Nunes. Oceanos, 49,110–128.

Leitão, H. (2006). Ars e ratio: A náutica e a constituição da ciência moderna. In M. V.Maroto & M. E. Piñeiro (Eds.), La ciencia y el mar (pp. 183–207). Valladolid: Losautores.

Leitão, H. (2007). Maritime discoveries and the discovery of Science. Pedro Nunesand early modern science. In V. Navarro-Brotóns & W. Eamon (Eds.), Más allá dela Leyenda Negra: España y la Revolución Científica. Beyond the Black Legend: Spainand the scientific revolution (pp. 89–104). Valencia: Instituto de Historia de laCiencia y Documentación López Piñero; Universitat de València; C.S.I.C.

Leitão, H., & Almeida, B. (2009). Pedro Nunes (1502–1578). Mathematics,cosmography and nautical Science in the 16th century. http://pedronunes.fc.ul.pt. Accessed 15.12.10.

de Medina, P. (1545). Arte de navegar en que se contienen todas las reglas,declaraciones, secretos y avisos, que a la buena navegacion son necesarios, y sedeven saber. Valladolid: F. Fernández de Córdoba.

de Monantheuil, H. (1599). Aristotelis mechanica: Graeca, emendata, latina facta, &commentariis illustratav. Paris: Ieremiam Perier.

Mota, B. (2011). O estatuto da matemática em Portugal nos séculos XVI e XVII. Lisboa:Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia.

Nunes, P. (1537). Tratado da sphera com a theorica do sol e da lua. E ho primeiro liuroda Geographia de Claudio Ptolomeo Alexãdrino. Tirados nouamente de Latim emlingoagem pello Doutor Pero Nunez Cosmographo del Rey dõ João ho terceyro destenome nosso Senhor. E acrec~etados de muitas annotações e figuras per que maysfacilmente se podem entender. Item dous tratados que o mesmo Doutor fez sobre aCarta de marear. Em os quaes se decrarão todas as principaes duuidas danauegação. Cõ as tauoas do mouimento do sol: e sua declinação. E o Regim~eto daaltura assi ao meyo dia: como nos outros tempos. Lisboa: Germão Galharde.

Nunes, P. (1542). Petri Nonii Salaciensis, De crepusculis liber unus, nunc recens & natuset editus. Item Allacen Arabis vetustissimi, de causis crepusculorum liber unus, aGerardo Cremonensi iam olim latinitate donatus, nunc vero omnium primum inlucem editus. Olyssippone: Ludovicus Rodericus.

Nunes, P. (1546). De erratis Orontii Finaei regii mathematicarum Lutetiae professoris.Qui putauit inter duas datas lineas, binas medias proportionales sub continuaproportione inuenisse, circulum quadrasse, cubum duplicasse, multangulumquodcunque rectilineum in circulo describendi, artem tradidisse & longitudinislocorum differentias aliter quam per eclipses lunares, etiam dato quouis temporemanifestas fecisse, Petrii Nonii Salaciensis Liber vnus. Coimbra: ex Officina IoannisBarrerii et Ioannnis Alvari.

Nunes, P. (1566). Petri Nonii Salaciensis Opera, quae complectuntur, primum, duoslibros, in quorum priore tractantur pulcherrima problemata. In altero traduntur exMathematicis disciplinis regulae et instrumenta artis nauigandi, quibus uaria rerumAstronomicarum uaimo9lema circa coelestium corporum motus explorarepossumus. Deinde, annotationes in Aristotelis Problema mechanicum de motunauigij ex remis. Basel: Officina Henricpetrina.

Nunes, P. (1567). Libro de Algebra en arithmetica y geometria. Compuesto por el DoctorPedro Nuñez, Cosmographo Mayor del Rey de Portugal, y Cathedratico Iubilado en laCathedra de Mathematicas en la Vniuersidad de Coymbra. Anvers: En casa de laBiuda y herederos de Iuan Stelsio.

Nunes, P. (2002). Obras vol. I. Lisboa: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian.Nunes, P. (2003). Obras vol. II. Lisboa: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian.Nunes, P. (2005). Obras vol. III. Lisboa: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian.Nunes, P. (2008). Obras vol. IV. Lisboa: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian.Nunes, P. (2010). Obras vol. VI. Lisboa: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian.Roberts, J. R., & Watson, A. G. (Eds.). (1990). John Dee’s library catalogue. London: The

Bibliographical Society.Rua, F. B. S. (2004). Relações entre John Dee e Pedro Nunes: A carta de Dee a

Mercator de 20 de Julho de 1558. Clio. Revista do Centro de Historia daUniversidade de Lisboa, 10, 81–109.

de Sá, D. (1549). De nauigatione libri tres quibus mathematicae disciplinae explicanturab Iacobo a Saa Equite Lusitano nuper in lucem editi. Paris: Officina ReginaldiCalderii et Claudii eius filii.

Sherman, W. H. (1995). John Dee: The politics of reading and writing in the EnglishRenaissance. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press.

Snell, W. (1624). Willebrodi Snellii à Royen R. F. Tiphys Batavus sive Histiodromice, denavium cursibus et re navali. Leiden: Officina Elzeviriana.

Tarrio, A. M. S. (2002). Do humanista Pedro Nunes. Oceanos, 49, 96–108.Taylor, E. G. R. (1938). The English debt to Portuguese nautical science in the 16th

century. I Congresso da História da Expansão Portuguesa no mundo, 1a Secção.Lisboa: Sociedade Nacional de Tipografia.

Taylor, E. G. R. (1954). The mathematical practitioners of Tudor and Stuart England.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press for the Institute of Navigation.

Taylor, E. G. R. (1963). Canon gubernauticus. An arithmeticall resolution of theparadoxall compas. In E. G. R. Taylor (Ed.), William Bourne, a regiment for the seaand other writings on navigation (pp. 419–433). Cambridge: Hakluyt Society atthe University Press.

Taylor, E. G. R. (1968). Tudor geography, 1485–1583. New York: Octagon Books.Taylor, E. G. R. (1971). The haven-finding art: A history of navigation from Odysseus to

Captain Cook. London: Hollis & Carter.Van Durme, M. (1959). Correspondance Mercatorienne. Anvers: De Nederlandsche

Boekhandel.Waters, D. (1958). The art of navigation in England in Elizabethan and early Stuart

times. London: Hollis & Carter.Woolley, B. (2001). The Queen’s conjuror: The science and magic of Dr John Dee, adviser

to Queen Elizabeth I. New York: Henry Holt & Co.Wright, E. (1599). Certaine errors in navigation, arising either of the ordinarie

erroneous making or using of the sea chart, compasse, crosse staffe, and tables of thesunne, and fixed starres detected and corrected. London: Valentine Sims.

Yates, F. A. (1979). The occult philosophy in the Elizabethan age. London: Routledge &Kegan Paul.

Further reading

Thomas, W. (1551). The sphere of Sacrobosco. Dedicated to the high and mightie PrinceHarry, Duke of Suffolk. British Library MS Egerton 837. London.