On the concept ofthird occipital headache · Onthe concept ofthirdoccipitalheadache Radiology The...

Transcript of On the concept ofthird occipital headache · Onthe concept ofthirdoccipitalheadache Radiology The...

Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 1986;49:775-780

On the concept of third occipital headacheNIKOLAI BOGDUK, ANTHONY MARSLAND

From the Pain Clinic, Princess Alexandra Hospital, and the Department ofAnatomy, University of Queensland,Brisbane, Australia

SUMMARY One of the putatative causes of headache is osteoarthritis of the C2-3 zygapophysialjoint. A technique for blocking the third occipital nerve which innervates this joint was devised andused as a screening procedure for headache mediated by this nerve. Seven out of ten consecutivepatients presenting with suspected cervical headache were found to suffer pain mediated by the thirdoccipital nerve and stemming from a C2-3 zygapophysial joint. Because third occipital headachemay be indistinguishable clinically from tension or other forms of headache, third occipital nerve

blocks are advocated as means of establishing this largely unrecognised diagnosis.

It is well recognised that disorders of the cervicalspine can be a source of headache' - and one suchdisorder is said to be osteoarthritis of the upper cervi-cal joints. ' - 7 The upper cervical joints consist of theatlanto-occipital joints, the median and lateralatlanto-axial joints, and the C2-3 zygapophysialjoints, but in general, these joints have been impli-cated only collectively in the pathogenesis of head-ache. Seldom has the symptom of headache actuallybeen ascribed to osteoarthritis specifically of one orother of these joints. In fact, no studies have demon-strated that osteoarthritis of the atlanto-occipitaljoints can be a cause of headache, while the medianatlanto-axial joint has been implicated only on thebasis of circumstantial radiological evidence.8 Fur-thermore, regardless of perhaps long-held con-victions, explicit evidence demonstrating that head-aches can be caused by osteoarthritis of the lateralatlanto-axial joints has only recently appeared.9The C2-3 zygapophysial joints are a less familiar

potential source of headache. Anatomically, thesejoints differ markedly from the other upper cervicalsynovial joints. Whereas the joints of the atlas lie ven-tral to the emerging spinal nerves, the C2-3zygapophysial joints lie behind the intervertebral for-amina in sequence with the other zygapophysial jointsand are the highest synovial joints associated with anintervertebral disc at the same level. Moreover, func-tionally they represent a transition zone between the

Address for reprint requests: Dr N Bogduk, Department ofAnatomy, University of Queensland, St Lucia, Queensland, 4067,Australia.

Received 2 April 1985 and in revised form 4 November 1985.Accepted 9 November 1985

C1-2 level, which accommodates rotation of the head,and the lower cervical spine, which accommodatesflexion and extension of the neck.10Our attention was drawn to the role of the C2-3

joints in the pathogenesis of headache by two clinicalreports. Trevor-Jones" reported three patients inwhom he found the third occipital nerve to beentrapped by osteophytes from an arthritic C2-3joint, and surgical release of the entrapment relievedtheir headaches. Maigne"2 reported 98 patients whoseheadaches he successfully treated with periarticularinjections of local anaesthetic and manipulation ofthe C2-3 joints. There are, however, certain lim-itations to these two reports. Interesting though hisfindings were, Trevor-Jones did not describe howpatients with third occipital nerve entrapment couldbe identified pre-operatively. The limitation ofMaigne's report is that he used particular injectionswithout radiological control, so it could be ques-tioned whether the relief he obtained was due toselective anaesthetisation of the C2-3 joint.

Notwithstanding these limitations, we wereprompted by these reports and our awareness ofthe biomechanical vulnerability of the C2-3zygapophysial joints to undertake a study of patientspresenting with occipital or suboccipital headache, totest the hypothesis that their pain stemmed from theC2-3 zygapophysial joints. A previous anatomicalstudy'3 had demonstrated the nerve supply to theC2-3 zygapophysial joints and the topographical andradiological disposition of the third occipital nerve,and this information was used to perform radio-logically controlled blocks of the nerves supplying theC2-3 zygapophysial joints in the patients selected forstudy.

775

by copyright. on June 10, 2020 by guest. P

rotectedhttp://jnnp.bm

j.com/

J Neurol N

eurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.49.7.775 on 1 July 1986. D

ownloaded from

performed. However, certain control observations were

made when the opportunity presented itself in the course ofrelated investigations or procedures. These included blocksof lower cervical dorsal rami"3 which were performed as a

screening procedure for intercurrent neck pain; C2 ganglionblocks,"4 which were performed to exclude headache medi-ated by the C2 spinal nerve; and in one case, an intra-muscular injection of local anaesthetic, performed during an

gon _<Asgs; l i attempted intra-articular injection of steroids.

E/s a 1 ~~~~Anatomy

TON The C3 dorsal ramus is a short nerve that arises from thespinal nerve and passes backwards through the C2-3 inter-transverse space where it divides into a lateral and two

s medial branches. The lateral branch supplies the more

superficial posterior cervical muscles."3 The deeper of theC3VR > [ N F u e !ktwo medial branches winds around the waist of the C3 artic-

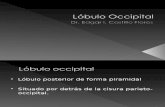

In[i ular pillar and enters the multifidus muscle. The superficialmedial branch is known as the third occipital nerve. Thisnerve crosses the lateral and dorsal aspects of the lower halfof the C2-3 zygapophysial joint (fig 1). It then passes across

-,.the lamina of C3 before turning backwards and upwards toC4VR W e pierce semispinalis capitis and splenius capitis to become

cutaneous over the suboccipital area. Articular branches ofthe C2-3 zygapophysial joint arise from the deep aspect ofthe third occipital nerve as it crosses the joint, or from a

Fig 1 A sketch of a posterolateral view of the left third communicating loop between the third occipital nerve andoccipital nerve (TON) seen crossing the lateral aspect and the C2 dorsal ramus, which crosses the dorsal aspect of thethen the dorsal aspect of the lower half of the C2-3 joint"3 (fig 1).zygapophysial joint. A branch to semispinalis capitis (s)arises from the nerve as it crosses the lamina of C3 and beforeit turns dorsally to enter the skin. Articular branches to thejoint arisefrom the deep aspect of the third occipital nerve orfrom the communicating loop (c) to the C2 dorsal ramus. 4 .. :X

The greater occipital nerve (gon) is shown crossing theobliquus inferior and rectus capitis posterior major, and thelateral (1) and deep medial (dm) branches of the C3 dorsalramus are shown crossing the C3 transverse process. VR:ventral rami.

Methods

Ten consecutive patients presenting with occipital or sub-occipital headache were studied. The headache history was

recorded in terms of site, radiation, frequency etc, according Uto the protocol suggested by Lance.5 A physical examinationwas performed including a thorough examination of theneck for abnormalities of movement and tenderness. Signsparticularly sought were tenderness over the cervicalzygapophysial joints, which was adopted as a putatative signof cervical arthropathy, and reproduction of head pain bysustained pressure over any site of tenderness.

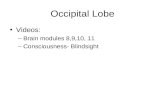

All patients underwent diagnostic blocks of the third Fig 2 A postero-anterior radiograph of the C2-3occipital nerve, ipsilateral to their complaint of pain, or zygapophysialjoints. The joints (zj) are seen as laterallybilaterally in cases of bilateral pain. Patients whose pain was convex silhouettes rising upwardsfrom the concavity of therelieved by blocking the third occipital nerve underwent two C3 articular pillar, opposite the level of the C2 spinousor more repeat blocks, at intervals between one week and process (sp), and below the lateral atlanto-axialjoints. Theone month, to confirm the response. target region for third occipital nerve blocks is shown by

Because of ethical considerations, related mainly to the dotted lines. A needle rests at the lowest of three sitesforradiation exposure involved in performing fluoroscopically injection (arrows) along the lateral margin of thecontrolled blocks, formal control blocks were not routinely radiographic silhouette.

Bogduk, Marsland776

i

by copyright. on June 10, 2020 by guest. P

rotectedhttp://jnnp.bm

j.com/

J Neurol N

eurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.49.7.775 on 1 July 1986. D

ownloaded from

On the concept of third occipital headache

RadiologyThe constancy of the course of the third occipital nerve

makes its location readily identifiable on postero-anteriorradiographs. The proximal part of the nerve crosses thelower half of the silhouette of the C2-3 zygapophysial joint.This landmark is recognised as a convexity that risesupwards from the concavity of the C3 articular pillar, andusually lies horizontally opposite the level of the C2 spinousprocess and C2-3 disc space (fig 2). Because of the orien-tation of the joint, a distinct joint space is not always visiblein a postero-anterior view, and cannot be relied upon as a

landmark. A needle introduced onto the lateral margin ofthe silhouette, between its mid-point and lower end, willreliably encounter the third occipital nerve proximal to theorigin of articular branches to the C2-3 joint.

Third Occipital Nerve BlocksThird occipital nerve blocks were performed usingfluoroscopic control with the patient lying prone on a table,the chest supported by a pillow and the head supported by a

firm sponge cushion, leaving the mouth unobstructed. TheC2-3 zygapophysial joint was visualised on the fluoroscopeby appropriately adjusting the head tilt and opening themouth.Once adequate orientation was achieved, the skin of the

back of the neck was prepared as for an aseptic procedureand a puncture site was selected over the posterolateralaspect of the neck at the level of the C2 spinous process. Thepuncture site was determined radiographically by adjustingthe position of the point of the needle on the skin so that itsradiographic projection lay just lateral to the silhouette ofthe C2-3 joint. A 22 gauge, 70mm needle was then insertedthrough the puncture site and directed ventrally and slightlymedially into the neck muscles. The course of the needle, as

it was advanced through the muscles, was repeatedlychecked fluoroscopically, every 1 to 2 cm, to ensure that ittravelled towards the back of the C2-3 joint. The dorsalaspect of the joint was the initial target in order to ensure theproper depth of insertion. Bony resistance coupled with theprojection of the needle's point over the joint indicated that

777

it lay dorsal to the joint, and had not been misdirected ven-trally in front of the joint. Once bone had been contacted,the needle was withdrawn slightly and readjusted laterallyuntil its tip lay on the lateral margin of the silhouette (fig 2),all adjustments being monitored by repeated screening.Proper location of the point of the needle was confirmedradiographically and by the sensation that it rested on bone.That it lay on the very lateral margin of the joint was

confirmed by adjusting the needle slightly more laterally tofeel it slip ventrally off the margin. It was then repositioned.To block the third occipital nerve, three injections of

0 5 ml of 0 5% bupivicaine were performed: one at the mid-point of the convexity of the silhouette, one at its lower end,and the last between these two. Three such injections thor-oughly bracket the course of the nerve, and the small volumeused, while adequate to block the target nerve, minimisedpossible spread to adjacent levels. At the end of the pro-cedure, the adequacy and accuracy of the block was

confirmed clinically by examining for anaesthesia in thecutaneous distribution of the third occipital nerve.

Results

The essential clinical features of the patients studiedare summarised in the table. All complained of occip-ital and suboccipital headache associated with painradiating to the forehead or related regions. All had atleast one feature that could be construed as sug-

gesting a cervical origin for their pain such as a his-tory of neck injury, precipitation of pain by neckmovement, or cervical tenderness. Only one patient(number 1 1) suffered the associated features of photo-phobia, nausea and vomiting that strongly suggesteda diagnosis of common migraine. Otherwise, the clin-ical features of the patients studied did not conformto those of any conventional diagnostic category,

Iable Clinicalfeatures

'atient Sex Age Onset History Site Radiation Quality Frequency Aggravating Tender Restricted(yr) factors movements

I M 46 IA 3 yr LSO L orbit Ache Constant Lifting Ex, Rot2 F 53 S 2 yr 0 Orbits Ache Constant Neck extension Fl, Ex, L Rot3 F 28 MVA 6 m SO Vertex Ache Constant Neck flexion C2-34 F 31 S 15 yr RO Vertex Ache Constant Reading C2-35 F 43 S 12 yr 0 Orbits Ache Constant - C2-36 F 30 MVA 3 yr RSO R orbit Ache Daily Neck movements Fl, Ex, R Rot7 F 34 MVA 12 yr RO - Ache Constant Neck movements C2-38 M 52 S 24 yr SO Orbits Throb Constant Stress SO9 M 52 S 20 yr SO Whole head Vice-like Constant - C2-3 Fl, Ex, Rot3 M 29 S 20 yr 0 Orbits Throb Constant Neck movements Nausea,

vomitingphotophobia

lotes: (1) The onset of headache is tabulated as spontaneous (S) or following an industrial accident (IA) or a motor vehicle accident (MVA). (2) The lengthf history is measured in years (yr) or months (m). (3) The principal site of pain is tabulated as suboccipital (SO) or occipital (0), prefixed by left (L) or right1) as appropriate. (4) C2-3 refers to tenderness over the C2-3 zygapophysial joints. SO refers to tenderness in the suboccipital region. (5) Abbreviations usedr movements are flexion (Fl), extension (Ex) and rotation (Rot) prefixed by left (L) or right (R) as appropriate. (6) Patient number 10 exhibited no signs inie neck, but suffered nausea, vomiting and photophobia.

by copyright. on June 10, 2020 by guest. P

rotectedhttp://jnnp.bm

j.com/

J Neurol N

eurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.49.7.775 on 1 July 1986. D

ownloaded from

778apart from possible cervical headache or perhapstension headache.

Seven of the ten patients responded to unilateraldiagnostic blocks of a third occipital nerve. The re-sponse was complete relief of all pain for the durationof action of the anaesthetic used, associated with theelimination ofaggravating factors. Subsequent blocksreproduced exactly the same relief. Three patients(numbers 9, 10 and 11) had no relief following blocksof their third occipital nerves bilaterally. Nor wasthere any relief following blocks of either the C4dorsal rami or the C2 ganglia.Control observations corroborated the response in

patients 1, 2, 5, 6 and 7. Patient number 1 underwentblocks of his C5, 6, 7 and C4 dorsal rami prior tothird occipital nerve blocks. During none of theseprocedures did he report relief of his headache, butrepeated blocks of his third occipital nerve consis-tently relieved his pain. This patient also underwent asingle-blind investigation comparing the responses toshort-acting (lignocaine) versus long-acting (bupivi-caine) local anaesthetic. His headache was relieved for1 hour after injection of lignocaine, but for 5 hoursafter using bupivicaine.

Patient number 2 underwent C2 ganglion blocks asher differential diagnosis included lateral atlanto-axial arthritis, but these did not relieve her headaches,whereas three blocks of her left third occipital nerveconsistently relieved her headaches, as did similarblocks on three further occasions in the course ofvarious therapeutic procedures.

Patient number 6 underwent blocks of her C5, 6dorsal rami in the initial course of the investigation ofher complaint of combined neck pain and headache.The C5, 6 blocks relieved her neck pain but did notinfluence her headaches. Reciprocally, the headaches,but not the neck pain, were repeatedly relieved byright third occipital nerve blocks.

Patient number 7 underwent a block of her rightgreater occipital nerve as her diagnosis included neu-roma formation on this nerve, but this did notinfluence her constant aching headaches which, onthe other hand, were relieved by third occipital nerveblocks.During an unsuccessful attempt at injecting ste-

roids into her right C2-3 zygapophysial joint, patientnumber 5 underwent an injection of local anaestheticdirected dorsal but superficial to the joint. This injec-tion did not involve the third occipital nerve becauseno numbness ensued, and did not relieve her head-ache, but three effective blocks of the third occipitalnerve, as evidence by numbness in the appropriatecutaneous field, succeeded in relieving her pain. Also,a single-blind block, using lignocaine instead of bupi-vicaine, had an appropriately shortened duration ofrelief.

Bogduk, Marsland

Discussion

That patients with C2-3 zygapophysial arthropathyshould suffer headache is not surprising. In the spinalcord, terminals of the C3 spinal nerve overlap withterminals of the trigeminal nerve,"s -17 and the con-vergence between cervical and trigeminal afferents inthe spinal grey matter provides a suitable neuro-anatomical substrate for the referral of pain to thehead.

Previous studies have shown that noxious stimu-lation of the muscles and ligaments innervated by theupper three cervical dorsal rami can produce head-ache in normal volunteers.'8'20 The referral patternof pain from cervical zygapophysial joints, however,has not been specifically studied, but such studieshave been done in the lumbar region wherezygapophysial pain can be referred to various regionsof the lower limb.2' 22 Extrapolation of these resultssuggests that noxious stimulation of the upper cervi-cal synovial joints could, like stimulation of the over-lying muscles, cause headache.

Third occipital nerve blocks were adopted in thisstudy because they provide a convenient means ofscreening for painful disorders mediated by thisnerve. The structures innervated by the third occipitalnerve are only skin, part of the semispinalis capitismuscle, and the C2-3 zygapophysial joint.'3 There areno occult conditions of the skin, and no known condi-tions selectively affecting only that portion of semi-spinalis innervated by C3, that cause headache. TheC2-3 zygapophysial joint is the only structure inner-vated by the third occipital nerve that could possiblybe a source of chronic pain. Therefore, we believe thatthird occipital nerve blocks are adequately selectivefor painful disorders of the C2-3 zygapophysial joints.We elected to use nerve blocks rather than direct

joint blocks because, technically, they are easier toperform and are less painful for the patient.Zygapophysial joint blocks involve a troublesomeinsertion of needles, and require screening in twoorthogonal planes. Another limitation is that, in thecase of markedly degenerated joints, it may notalways be possible to introduce a needle into theeroded joint cavity. Moreover, although joint blocksmight appear to be more selective for joint disorders,there is no guarantee that local anaesthetic, injectedintra-articularly, remains within a zygapophysialjoint cavity. Any leakage outside the joint compro-mises the selectivity of the block. For this reason wedo not believe C2-3 joint blocks are necessarily supe-rior to third occipital nerve blocks as a screeningprocedure for pain from these joints.The procedure we used is notably free of risks or

major side effects. There are no major structures inthe region injected. The vertebral artery lies ventral to

by copyright. on June 10, 2020 by guest. P

rotectedhttp://jnnp.bm

j.com/

J Neurol N

eurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.49.7.775 on 1 July 1986. D

ownloaded from

On the concept of third occipital headache

zygapophysial joints, and so is protected from inad-vertent puncture, so long as a posterior approach tothe third occipital nerve is used. The spinal cord lieswell medial to the target site for the local anaestheticblocks, and so is not at risk, but it is to ensure thatneedles are not deflected towards the cord thatrepeated fluoroscopic screening should be used tomonitor the progress of the needle. Similarly, pene-tration of the epidural space is avoided by directingthe course of the needle strictly towards thezygapophysial joint. There should be no risk of theanaesthetic tracking into the epidural space, so longas the ligamentum flavum is intact, for this structureseals off the epidural space from the posterior mus-cular compartment into which the anaesthetic isinjected.

Otherwise, those precautions appropriate to anyprocedure involving the injection of local ana-esthetics, need to be taken. The syringe should bedrawn back prior to injection to avoid inadvertentintravascular injection into an intra-muscular vein,and the operator should be fully prepared to deal withthe consequences of systemic injection or the rareallergic reaction to local anaesthetic.There is, however, one possible side-effect peculiar

to injections in the upper cervical region, and this thecomplaint of light-headedness, dizziness or slightataxia. It is due to interference by the local ana-esthetic with the proprioceptive afferents from theupper cervical muscles involved in the tonic neckreflex, and has been discussed in previous studies ofupper cervical blocks.14 It was reported regularly byour patients who, indeed, were forewarned of the pos-sibility. The effect never outlasted the duration ofaction of the local anaesthetic used, and usuallywaned well before the pain relief ceased. It was neverserious or incapacitating. By forewarning patients,and coaching them to rely more on visual cues forbalance (by concentrating on the horizontal whenwalking), and reassuring that it is only a temporaryeffect, this side effect is easily tolerated.Whereas third occipital nerve blocks can be used to

demonstrate that a C2-3 zygapophysial joint is thesource of pain, these blocks, per se, do not reveal itsactual cause. However, the causative pathology, inour cases, was most likely traumatic arthropathy ordegenerative joint disease. Patients 1, 3, 6 and 7 allhad histories of recent injuries to the neck, andpatient 4 had a history of epilepsy since childhoodthat involved frequent falls. Thus, all of these patientscould be viewed as possibly having sustained aninjury to a C2-3 zygapophysial joint. Patient 2 had ahistory of diffuse degenerative disease of the spine,and it seemed not inappropriate that, as part of thisdisease, her C2-3 joints were involved.

Analysis of the clinical features of our patients

779

failed to reveal any feature that might be construed aspathognomonic of third occipital headache or thatmight be used as a specific indication for third occipi-tal nerve blocks. Although restricted neck movementsand zygapophysial tenderness were adopted as puta-tative diagnostic signs, these features occurred inpatients who failed to respond to adequate blocks ofthe third occipital nerve. Furthermore, plain radio-graphs of the neck revealed no feature in any of ourpatients that could be construed as indicative of C2-3arthropathy. Thus, the only diagnostic feature ofthird occipital headache is positive response to thirdoccipital nerve blocks, and it is our suggestion thatthese blocks should be performed whenever an alter-native diagnosis cannot be confirmed and when thirdoccipital headache might be suspected in thedifferential diagnosis of occipital pain.

Whereas we concluded that those patients whoresponsed to third occipital nerve blocks weresuffering pain stemming from their C2-3 zygapo-physial joints, this diagnosis was excluded in the threepatients who did not respond. The associated featuresof nausea, vomiting and photophobia described bypatient 10 allowed us to endorse the diagnosis ofcom-mon migraine, and accordingly, it is not suiprisingthat he did not respond to cervical nerve blocks.Patients 8 and 9 did not have features that permitteda diagnosis of migraine to be made with any certainty,but in patient number 8 migraine was considered themost likely differential diagnosis, and he, like patient10, was referred for further neurological manage-ment. The limitations of neck movements describedby patient 9 still strongly suggested a cervical causefor his headache, but his failure to respond to thirdoccipital and C2 ganglion blocks excluded a source ofpain in the territories of these nerves, and he wasreferred for further investigation of his headaches andneck pain.The principal aim of our report has been to endorse

the concept of headache mediated by the third occipi-tal nerve and stemming from the C2-3 zygapophysialjoints, and to describe a means of objectively screen-ing for and confirming this diagnosis. It was not ourintention to address the issue of treatment, for this isstill being evaluated. Howevei, to assuage any lin-gering doubts about our proposed concept, we offer abrief summary of the therapeutic responses of ourpatients.The patients have variously been treated by several

techniques. These include intra-articular injections ofsteroids, cryocoagulation and radiofrequency coagu-lation of the third occipital nerve, and even open neu-rectomy. When used, each of these techniques pro-vided total and sustained relief from headache. Theconfounding issue, however, has been the longevity ofresponse that we have attained. Steroids have worked

by copyright. on June 10, 2020 by guest. P

rotectedhttp://jnnp.bm

j.com/

J Neurol N

eurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.49.7.775 on 1 July 1986. D

ownloaded from

780

for periods of between 2 weeks and 4 months. Cryo-coagulation has lasted between three and six weeks,while radiofrequency coagulation has produced reliefin excess of 3 months, and has lasted 12 months in onecase. Open neurectomy has achieved the longestresponses, so far, of 18 and 24 months.We offer this summary of therapy, however, not to

recommend any particular technique, but to illustratethat, having made the diagnosis of third occipitalheadache stemming from a C2-3 zygapophysial joint,treatment directed at either the joint or its nerve

supply succeeded in producing relief. The recurrenceofpain is the problem, but we do not interpret it as anindictment of the diagnosis, but rather as reflectingthe limitations of the therapeutic techniques used.Steroids may not be applicable in arthropathy that isperhaps not inflammatory, and neurotomy is com-

promised by the eventual regeneration of the nerve.

Our further studies are directed at refining the indi-cations and optimal application of these techniques.With respect to open neurectomy, while this

appeared a legitimate option in two of our earlypatients and was effective in relieving their headache,one of them developed neuroma pain that eventuallyhad to be treated by C3 rhizotomy. It is because of thedevelopment of iatrogenic neuromata that we adviseagainst using third occipital neurectomy until ade-quate means of combating neuroma formation are

devised.It is perhaps remarkable that we identified seven

patients with third occipital headache in a consecutiveseries of ten patients, but we point out that this wasnot due to any preselection on our part, and rather,probably reflects the referral pattern to our PainClinic at the time of the study. However, this highincidence may, alternatively, reflect an actual highincidence in the community of a condition that hasremained unrecognised by specialists dealing withheadache, and perhaps misdiagnosed as tension head-ache. It is for this reason, and lest such patients con-

tinue to remain unrecognised, that we report the con-

cept of third occipital headache and a means for itsobjective diagnosis.

In this context, third occipital headache must beviewed as only one of the possible differential diag-noses of headaches of cervical origin. As mentioned inthe introduction, arthritis of the C1-2 joints is anotherpossibility. However, at present, there are no estab-lished, validated clinical clues that might be used by a

practitioner to determine beforehand which patientswill respond to third occipital, as opposed to CI-2, or

other, blocks. We suggest only that a high degree ofsuspicion be maintained in patients with occipitalpain of unknown origin, and advise that an arma-

mentarium of techniques is available to pursue thediagnosis. Descriptions of techniques to block the lat-

Bogduk, Marsland

eral atlanto-axial joints,9 the C2 ganglion,14 and thelower cervical dorsal rami'3 are available in the litera-ture. To these we now add the technique for thirdoccipital nerve blocks.

References

Ad Hoc Committee on Classification of Headache.Classification of headache. JAMA 1962;179:717-8.

2Adams RD. Headache. In: Petersdorf RG, Adams RD,Braunwald E, Isselbacher KJ, Martin JB, Wilson JD,eds. Harrison's Principles ofInternal Medicine. 10th ed.New York: MzGraw-Hill, 1983;Ch 3:15-25.

3Edmeads J. Headaches and head pains associated withdiseases of the cervical spine. Med Clin North Am1978;62:533-44.

4Friedman AP. Headache. In: Baker AB, Baker LH, eds.Clinical Neurology. Vol 2. Philadelphia: Harper andRow, 1983;Ch 13:1-50.

5 Lance JW. Mechanism and Management ofHeadache. 4thed. London: Butterworths, 1982.

6 Wilkinson M. Symptomatology. In: Wilkinson M, ed.Cervical Spondylosis. 2nd ed. London: Heinemann,1971;Ch 4:59-67.

'Brain L. Some unsolved problems of cervical spondylosis.Br Med J 1963;1:771-7.

8Fournier AM, Rathelot P. L'arthrose atlo-odontoidienne.Presse Medicale 1960;68:163-5.

9Ehni G, Benner B. Occipital neuralgia and the C1-2arthrosis syndrome. J Neurosurg 1984;61:961-5.

10Mestdagh H. Morphological aspects and biomechanicalproperties of the vertebroaxial joint (C2-C3). ActaMorphol Neerlando-Scand 1976;14:19-30.

l Trevor-Jones R. Osteoarthritis of the paravertebral jointsof the second and third cervical vertebrae as a cause ofoccipital headache. S Afr Med J 1964;38:392-4.

12Maigne R,. Signes cliniques des cephalees cervicales: leurtraitement. Medecine et Hygiene 1981;39:1174-85.

13Bogduk N. The clinical anatomy of the cervical dorsalrami. Spine 1982;7:319-30.

4Bogduk N. Local anaesthetic blocks of the second cervicalganglion. A technique with application in occipitalheadache. Cephalalgia 1981;1:41-50.

"5Kerr FWL. Structural relation of the trigeminal spinaltract to upper cervical roots and the solitary nucleus inthe cat. Exp Neurol 1961;4:134-48.

16Escolar J. The afferent connections of the 1st, 2nd, and3rd cervical nerves in the cat. J Comp Neurol 1948;89:79-92.

7Kerr FWL, Olafson RA. Trigeminal and cervical volleys.Arch Neurol 1961;5:171-8.

Cyriax J. Rheumatic headache. Br Med J 1938;2:1367-8.9Campbell DG, Parsons CM. Referred head pain and its

concomitants. J Nerv Ment Dis 1944;99:544-51.20Feinstein B, .Langton JBK, Jameson RM, Schiller F.

Experiments on referred pain from deep somatic tis-sues. J Bone Joint Surg 1954;36A:981-97.

21McCall IW, Park WM, O'Brien JP. Induced pain referralfrom posterior lumbar elements in normal subjects.Spine 1979;4:441-6.

22Mooney V, Robertson J. The facet syndrome. Clin Orthop1976;115: 149-56.

by copyright. on June 10, 2020 by guest. P

rotectedhttp://jnnp.bm

j.com/

J Neurol N

eurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.49.7.775 on 1 July 1986. D

ownloaded from