On Physical Mockups in the Age of Digital Reproducibility” WUHO

Transcript of On Physical Mockups in the Age of Digital Reproducibility” WUHO

8/11/2019 On Physical Mockups in the Age of Digital Reproducibility” WUHO

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/on-physical-mockups-in-the-age-of-digital-reproducibility-wuho 1/2

A

Mario Carpo

The full-size, three-dimensional mockup is a fixture of the industrial age. If one plans to reproduce the same bottle one billion times, it makes sense to study, try and test it many times over, in real size and in real life, before the blueprint is sent to the factory. The same would apply to a prefabricated, precast concrete panelmeant to standardize all social housing for all times to come in all countries around the world or, moremodestly, to a modular curtain wall panel which will be reproduced 2,784 times to clad a black office tower designed for a financial firm which will soon vacate it to relocate in Bangalore.

The technical logic of mechanical mass production maximizes economies of scale on the condition that, after the machine is set in motion, it keeps churning out identical copies of whatever it is making for as long as possible. All changes and adjustments that interrupt serial reproduction entail additional expenditures:matrixes, molds and casts have to be remade, the assembly line reset, and costs pile up. Hence the importanceof thoroughly testing a mockup before mass replication. Better safe than sorry.

Traditional hand-making does not work that way. A craftsman—say, a preindustrial cobbler—does not makefull-size mockups of shoes, because every pair of shoes he makes—indeed, every shoe he makes—is amockup of itself. As all are custom-made, each item is made to fit the foot of each individual customer. Whenit fits, it ships; and until it doesn’t, the cobbler will keep working on it. Of course, today’s luxury bespokeshoemakers may keep a few ready-made examples in their shops, to show off their bravura, or to orient the

Physical Mockups in the Age of Digital Reproducibility” | WUHO http://wuho.

9/6/2011 1

8/11/2019 On Physical Mockups in the Age of Digital Reproducibility” WUHO

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/on-physical-mockups-in-the-age-of-digital-reproducibility-wuho 2/2

choices of their customers; but those presentation pieces do not count, functionally, as mockups as they arenot for testing, nor for trial, nor prototypes meant for identical Reproduzierbarkeit . The real work of art is theunique piece that will start to be made only after each foot of the discerning client has walked into the shop.

Occasionally, even craftsmen are asked to produce identical copies–which free-hand making as a rule is notvery good at. The builders of classical Greek temples, for example, often had to reproduce a certain number of identical capitals. Archeologists assume that in such instances, ancient stonecutters first made one capital, toserve as a template, or archetype (they actually called it paradeigma, or example), and then copied it as many

times as necessary; when all capitals were done and put in place, on top of each respective column, capitalnumber one would go the same way, as it was just the same as all others. But this procedure was and is theexception: hand-making, in most walks of life, does not aim at identical copies; quite the contrary, it aims atmaking each item on its own merit.

Digital making, once again, partakes of both mechanical machine making and traditional hand-making, but it pertains to neither. Digital making straddles boundaries, hybridizes or muddles established patterns of use, and it may discombobulate, or worse, both makers and users. Digital notations may drift, change and morph all thetime, because often they are scripted parametrically, and as the name indicates, parameters are meant to be parametrized. The customization of the original script may be the work of the persons who wrote that script,or not. Parameters that are free to vary may be set randomly, or automatically, or by a person whom we have

never met. Additionally, the script itself—besides its parametric variables—may be tweaked or edited or transmogrified, by chance or by design; and even the software we use to write that script may be differenttomorrow from what it is today. In short, achieving identical copies in a digital design and production chain isdifficult, sometimes impossible—and in any event, it is alien to the spirit of the game.

This is why digitally fabricated mockups do not and cannot work as old pre-digital mockups once did. Everyinstantiation of a digital script is a unique epiphany of sorts: occasional, ephemeral, and often unrepeatable.The next one in the same series will be different—albeit similar, as most of the script may still be the same.You may look at that digitally fabricated physical mockup and think that it is a sign of more to come, but thiswill be only partially true: as in all digital series, each item is only the evocation of more that may come, moreor less similar to the first spin-off—but never the same. In the old mechanical world, a physical mockup—the

archetype of the series—was one out of many that would be just the same; in a digital parametricenvironment, the algorithm is one into many that will all be different. The individual mockup may still stand for the whole series, but only in a vague, generic, and suggestive way: it stands for the series like a potato plant we bought in a pot may stand for the whole garden, or, in a metaphor which John Ruskin would havefound more to his taste, like the first lilies that peep through the melting snow at the end of winter promise the bed of flowers that will adorn the meadow when the spring cometh.

So it is good to play around the ambiguity of today’s mockups and probe the queries they raise. For everydigitally fabricated mockup is bound to be, to some extent, a trompe l’oeil that cheats our eyes used to and trained by the worn-out logic of mechanical mass-production; indeed, it mocks them.

21 February 2011

Mario Carpo is Associate Professor of Architectural History in the French Schools of Architecture, Professor at the Georgia Institute of Technology, and Vincent Scully Visiting Professor of Architectural History at theSchool of Architecture of Yale University. He is the author of The Alphabet and the Algorithm (MIT Press,2011), Architecture in the Age of Printing (MIT Press, 2001); and other books.

Published in conjunction with the WUHO Exhibition, Mockups.

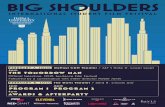

Image: Jennifer Bonner’s project in the Mockups exhibition at WUHO.

Physical Mockups in the Age of Digital Reproducibility” | WUHO http://wuho.

9/6/2011 1

![For the Record [Adorno on Music in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility]](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/577cd03c1a28ab9e7891c1dc/for-the-record-adorno-on-music-in-the-age-of-its-technological-reproducibility.jpg)