Olsen 2005 Trade and Conservation of Himalayan Medicinal Plants

-

Upload

adina-roxana-munteanu -

Category

Documents

-

view

83 -

download

2

Transcript of Olsen 2005 Trade and Conservation of Himalayan Medicinal Plants

www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon

Biological Conservation 125 (2005) 505–514

BIOLOGICAL

CONSERVATION

Trade and conservation of Himalayan medicinal plants:Nardostachys grandiflora DC. and Neopicrorhiza scrophulariiflora

(Pennell) Hong

C.S. Olsen *

The Royal Veterinary and Agricultural University, Centre for Forest, Landscape and Planning, Rolighedsvej 23, 1958 Frederiksberg C, Denmark

Received 11 June 2004

Available online 2 June 2005

Abstract

There is a large annual international trade in the rhizomes of the alpine Himalayan perennials Nardostachys grandiflora DC. and

Neopicrorhiza scrophulariiflora (Pennell) Hong, both species in a monotypic genus. This paper estimates the range of the annual trade

levels and discusses the conservation implications. Data was collected through a nation-wide survey inNepal using standardised open-

ended interviews with 223 harvesters, 149 local traders, 90 central wholesalers, 53 regional wholesalers, and 16 processing industries.

Data collection allowed cross-checking of findings by comparing an annual supply estimate and an annual consumption estimate.

Regarding methodology, it is concluded that using agents� own-reported values results in reliable volume and value estimates; how-

ever, validity should be treated with caution, as there is evidence of systematic bias in price reporting and underestimation of quan-

tities. Trade data is thus evaluated to constitute conservative estimates, with local trader derived data being more valid than

wholesaler derived data. Annual trade levels fromNepal are estimated at 100–500 tonnes ofN. grandiflora rhizomes and 175–770 ton-

nes of N. scrophulariiflora rhizomes. In the case year of 1997/1998, the respective global amounts were estimated at 350–400 and 650–

1000 tonnes (of which a maximum of 50–300 tonnes are from Picrorhiza kurrooa whose rhizomes are mixed with P. scrophulariiflora

and traded under the name kutki) with a total CIF value of USD 2.7–3.6 million. Nepal is the main supplier (82 ± 5% ofN. grandiflora

and 66 ± 12 of kutki) followed by India (13 ± 5 and 19 ± 12) and Bhutan (5 ± 4 and 14 ± 8). The importance of applying a regional

approach to conservation of the species is emphasised, as is the need for improved official trade monitoring by governments.

� 2005 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Non-timber forest products; Trade; Conservation; CITES; Nepal; India; Himalayas

1. Introduction

Himalayan medicinal plants appear to have beentraded for millennia (Jacob and Jacob, 1993). However,

only in recent years have commercially traded Himala-

yan plant species received scientific attention as their po-

tential for contributing to rural livelihoods are being

discussed, as are the conservation consequences of har-

vest and trade. Recent studies have focused on identify-

ing the species and products in trade (e.g., Manandhar,

0006-3207/$ - see front matter � 2005 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2005.04.013

* Tel: +45 3528 1763.

E-mail address: [email protected].

1980; Murty, 1993), outlining trade patterns (e.g.,

Farooquee and Saxena, 1996; Holley and Cherla,

1998; Olsen, 1998; Mulliken, 2000), assessing policyand legislative environments (e.g., Olsen and Helles,

1997; Larsen et al., 2000), investigating local resource

management systems (e.g., Larsen, 2002), examining

cultivation and domestication issues (e.g., Hertog and

Wiersum, 2000; Nadeem et al., 2000) and estimating

the importance of trade to rural harvesters (e.g., Olsen

and Larsen, 2003). It has been established that products

from hundreds of species are being traded, that tradespans from remote forests and meadows to international

markets and consumers, that almost all traded material

506 C.S. Olsen / Biological Conservation 125 (2005) 505–514

is harvested in the wild, that markets are working even if

they are not perfect, and that harvest and sale provides

an important source of income to a huge number of rur-

al households. However, for all species, data on annual

quantities traded remain scarce or non-existent. Almost

all trade studies are conducted at local level and can notbe used to draw general conclusions at the species, mar-

ket or national level.

Lack of data also impedes assessment of the conser-

vation status of the traded species. Local level assess-

ments are available for some species and locations

(e.g., Kala, 2000; Rai et al., 2000), but no systematic

assessment has been conducted for any of the major

traded species across their distribution area. Conserva-tion Assessment and Management Plan (CAMP) work-

shops have been conducted for Jammu-Kashmir and

Himachal Pradesh (Ved and Tandon, 1998) and Nepal

(Tandon et al., 2001). The most widely held conserva-

tion view on commercial Himalayan medicinal plant

species is that a large number of species are endangered

due to a combination of over-harvesting and habitat

destruction (e.g., Shrestha and Joshi, 1996; Rai et al.,2000). Due to lack of solid empirical data, the scientific

foundation of the view is weak. Recent attempts to de-

sign systematic approaches to medicinal plant conserva-

tion priority setting (Cunningham, 1997; Dhar et al.,

2000) emphasise the need for combining trade data

and biological information at the species level.

1.1. Nardostachys grandiflora and Neopicrorhiza

scrophulariiflora

There has been much interest in the species N. gran-

diflora DC. (syn. N. jatamansi DC. and N. chinensis

Batal.) and N. scrophulariiflora (Pennell) Hong (syn.

Picrorhiza scrophulariiflora Pennell) from both trade-

livelihood and conservation points of view. Both species

are alpine perennial herbs found only in the Himalayas.Both are species in a monotypic genus. The rhizomes of

both species are collected by local harvesters throughout

the Himalayas and the air-dried rhizomes are traded

along well-established marketing chains from the alpine

meadows to the cities on the plains of India. The two

species provide almost 50% of the total annual income

from alpine medicinal plant harvest in Nepal and har-

vesting constitutes an integrated part of harvesters� live-lihood strategies (Olsen and Larsen, 2003). Other studies

indicate that the species may have some importance to

rural livelihoods across the Himalayas (Farooquee and

Saxena, 1996; Rai et al., 2000). Furthermore, there are

indications of a rising demand for Himalayan plant

based medicinal and cosmetic products (Holley and

Cherla, 1998; Olsen, 1998) that could lead to increased

harvest levels of the two species.N. grandiflora has been reported from India, Nepal,

Bhutan and South-west China from 3600–4800 masl

(Polunin and Stainton, 1984) but may also occur in

Afghanistan and Pakistan (Mulliken, 2000). N. scro-

phulariiflora is found from westernmost Nepal to Bhu-

tan and Yunnan in China from 3600–4800 masl

(Polunin and Stainton, 1984; Smit, 2000). It may also

occur just west of Nepal in the Indian Garhwal Hima-laya (Smit, 2000).

Some authors regard P. scrophulariiflora as a synonym

for P. kurrooa Royle ex Benth. rather than an indepen-

dent species. However, taxonomical differences arguably

warrant distinction between two monotypic genera

(Hong, 1984; Smit, 2000). N. scrophulariiflora (Pennell)

Hong has been reserved as the official name of the species

(Brummitt, 1992) and is used here. Rhizomes of P. kur-rooa (from western Himalaya) and N. scrophulariiflora

(from central and eastern Himalaya) both enter trade un-

der the name kutki. The rhizomes of the two kutki species

are morphologically similar and are not distinguished in

trade. N. grandiflora and P. kurrooa were included in

CITES Appendix II in 1997; the annotation includes

the ‘‘whole and sliced roots and parts of the roots, exclud-

ing manufactured parts or derivatives’’ which is taken toinclude the rhizomes (Mulliken, 2000). N. scrophulariifl-

ora is not CITES listed. Both N. grandiflora and N. scro-

phulariiflora have been assessed as being vulnerable in

Nepal (Tandon et al., 2001).

1.2. Objectives of the paper

Thus, the two species form an interesting case as theyare: (i) harvested destructively, i.e., up-rooted, in large

quantities, (ii) important for income generation in a

large number of rural households, (iii) traded across na-

tional borders, (iv) distributed only in alpine habitats in

the Himalayas, and (v) both phylogenetic distinct,

occurring in monotypic genera. N. scrophulariiflora is

further interesting as the traded rhizomes are mixed with

morphologically similar rhizomes from the CITESAppendix II listed species P. kurrooa. A TRAFFIC re-

port to the CITES secretariat (Mulliken, 2000) has also

emphasised the need for further investigation of the

trade in these species. On the basis of empirical data,

the present paper provides a national level estimate of

the volume and value of trade in air-dried rhizomes of

N. grandiflora and N. scrophulariiflora from Nepal,

and estimates the importance of the Himalayan statesas suppliers of the products jatamansi and kutki. The

conservation implications of the findings are discussed.

2. Methods

Anational level investigation of themedicinal and aro-

matic plant trade in and from Nepal was designed. Fieldwork was conducted from August 1998 to September

1999 and covered a set of products including the rhizomes

C.S. Olsen / Biological Conservation 125 (2005) 505–514 507

ofN. grandiflora andN. scrophulariiflora. General data as

well as data for the case year 1997/1998 were collected.

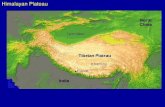

Nepal was stratified into 15 cells using the three main

physiographic zones and five development regions as

proxies for altitude and climatic variations. In each cell,

a district was randomly chosen, see Fig. 1. In each district,all local traders (n = 149 of which 32 tradedN. grandiflora

and 48 traded N. scrophulariiflora) were identified and

interviewed. Harvesters (n = 223), gathering the two spe-

cies in the chosen districts, were randomly met en route

and interviewed. All 90 exporters of medicinal and aro-

matic plants to India in the case year of 1997/1998

(n = 20 forN. grandiflora rhizomes and n = 30 forN. scro-

phulariiflora) were interviewed. A total of 53 wholesalersin India (n = 38 trading N. grandiflora and n = 32 for N.

scrophulariiflora) were located and interviewed in the se-

ven main cities importing medicinal plants from Nepal

(Delhi, Lucknow, Kanpur, Kannauj, Siliguri, Tanakpur,

Calcutta). All interviews were conducted using standar-

dised open-ended questionnaires. Copies of invoices,

including details of products exported, amounts and

prices, kept in the Department of Foreign Trade wereanalysed to investigate export to countries other than In-

dia and China in the case year 1997/1998. Finally, 16

domestic Nepalese producers using medicinal and aro-

matic plants were interviewed to obtain an overview of

the domestic demand for the species.

Thus, assuming no stock-piling or depletion in the

chain of commerce, data allows a comparison of two

estimates of the same trade: (i) an annual supply esti-

High mountains

Middle hills

Terai

80o N

30o E

Development region border

FAR WESTERN

MID-WESTERN

WESTERN

Darchula Humla

Mustang

Case district border

INDIA

Baitadi

Rupandehi

Palpa

Dang

Surkhet

Kailali

Fig. 1. Field work districts, physiograph

mate calculated as the annual amount entering trade,

derived from the local trader survey, and (ii) an annual

consumption estimate calculated as the sum of export to

India, China, third countries and domestic industrial

demand.

2.1. Data analysis

The district level data (15 districts) was generalised to

the national level (75 districts) by extrapolating the find-

ings in each district to the other districts in the same cell.

The number of districts in each cell varied from 2 to 10.

It is assumed that vegetation distribution, quality and

harvesting pressure is similar within cells. Generalisationof findings to other districts in the same cell was done on

the basis of the potential growing area of each species in

each district and using an ecological zone adjustment

factor:

Qij ¼ ðpij=picÞejcQic ð1Þ

where Qij is the estimated amount (kg) of species i

(i = 1,2) traded from district j (j = 1,2, . . . , 60); pij is

the estimated potential growing area of species i in dis-trict j; pic is the estimated potential growing area of spe-

cies i in case district c (c = 1,2, . . . , 15) in the cell

containing district j; ejc is the ecological zone adjustment

factor calculated as the alpine vegetation area in district

j divided by that in the case district c in the cell contain-

ing district j; and Qic is the recorded amount (kg) of

product from species i traded from the case district c.

N

200 km

CENTRALEASTERN

Nuwakot

Dolakha

Taplejung

TIBET

Rautahat

Udaipur

Morang

ic zones and development regions.

508 C.S. Olsen / Biological Conservation 125 (2005) 505–514

Estimation of the potential growing area was done:

(i) the altitudinal range of the species in Nepal was esti-

mated based on the voucher specimens in the Kath-

mandu National Herbarium in Godovari and informal

discussions with botanists, (ii) this range was related to

the altitudinal distribution of ecological zones describedby Lillesø et al. (2001), and (iii) the area of the relevant

ecological zones were calculated for each district using

the percentage distribution of ecological zones for all dis-

tricts in Nepal provided by Lillesø et al. (2001). In step

one, the altitudinal range of N. grandiflora was estimated

at 3200–4500 masl, and at 3500–4800 for N. scro-

phulariiflora. These estimates are close to those found

in the literature for the entire distribution range (Poluninand Stainton, 1984) and for Nepal (Shrestha and Joshi,

1996). In step two, both species were assigned to the

sub-alpine (3000–4000 masl), alpine (4000–5000) and

transhimalayan (>3000) ecological zones. In step three,

the altitudinal range and distribution across ecological

zones is combined with the district size to calculate the

potential growing area of the species in the district,

e.g., 18.6% of Baglung District is found in the sub-alpinezone; this gives a potential growing area ofN. grandiflora

of (800/1000*0.186*district size) in that ecological zone.

For calculations regarding the transhimalayan ecological

zone, the upper limit of the zone is set at 5000 masl.

The ecological zone adjustment factor is used as there

may be differences in the actual area of vegetation be-

tween districts that have a similar potential growing

area. Ideally, the factor should be calculated based onthe actual area of the vegetation types in which the spe-

cies occurs while taking into account the species� altitu-dinal range. However, this information is not available.

Instead, the area of alpine vegetation in each district is

assumed equal to the area of High Himalaya and High

Mountain pastures in each district using the estimates

provided by ISRSC (2001).

The total supply from Nepal of each species is calcu-lated as the sum of findings from each of the 75 districts.

Table 1

Amount and value of annual export of unprocessed N. grandiflora (jatamansi)

based on central wholesaler interviews

Development

region

Low estimatea High estimatea 1997/

Jatamansi Kutki Jatamansi Kutki Jatam

Eastern 17 30.5 41.5 126 24.5

Central 2 9 8 39 5

Western 10 16 50 50 50

Mid-western 69 37.3 326 152 204

Far-western 3.5 8.5 11 39 5.8

Nepal 101.5 101.3 436.5 406 289.3

All amounts in tonnes, all values in �000 USD (68 Nepalese rupees/USD).a Derived from interviews with all central wholesalers (exporters) of N. gran

wholesalers.b Calculated as ((low + high estimates)/2)*av. buying price in India in 1997

is derived from interviews with regional wholesalers importing N. grandiflora

2.8 ± 0.2 USD/kg, respectively.

Note that data collection allows the district estimate Qij

to be calculated as the minimum amount traded in a bad

year, the maximum amount traded in a good year, as

well as the amount traded in the case year 1997/1998.

2.2. Cross-checking own-reported values

The trade data relies on the interviewed agents� own-estimates of values. These values may be incorrect, e.g.,

if regional wholesalers feel obliged to answer questions

but do not wish to disclose information. It is thus neces-

sary to evaluate the quality of the obtained data on

prices and quantities. This is done by: (i) calculating ba-

sic distributional statistics for prices in locations withmany buyers (if responses are invalid, a high degree of

randomness in responses would be expected), (ii) com-

paring reported buying and selling prices in the same

location, and (iii) comparing findings on amounts to

previous studies.

3. Results

The findings on trade in air-dried rhizomes of N.

grandiflora and N. scrophulariiflora are presented in five

parts: (i) estimating annual consumption of plant mate-

rial from Nepal, (ii) estimating annual supply from Ne-

pal, (iii) estimating global supply, (iv) presenting an

overview of regional wholesalers� knowledge of trade re-lated legislation, and (v) presenting data on the financialimportance of harvest to rural livelihoods.

3.1. Estimating annual consumption

3.1.1. Export to India

Figures for export of unprocessed air-dried rhizomes

of N. grandiflora and N. scrophulariiflora from Nepal to

India, based on interviews with central wholesalers (theexporters), are presented in Table 1. There is a large

and N. scrophulariiflora (kutki) air-dried rhizomes from Nepal to India

1998 estimatea Av. export valueb 1997/1998 export value

ansi Kutki Jatamansi Kutki Jatamansi Kutki

100.5 66 220 55 283

22 11 68 11 62

31 67 93 112 87

78.1 443 266 458 220

29 16 67 13 82

260.6 603 714 649 734

diflora (n = 20) and N. scrophulariiflora (n = 30); excludes trade between

/1998 (including transport from Nepal, CIF price). The av. buying price

(n = 37) and N. scrophulariiflora (n = 32) and estimated at 2.2 ± 0.2 and

C.S. Olsen / Biological Conservation 125 (2005) 505–514 509

variation in yearly amount and value of the export; the

annual export ranges from 100 to 435 tonnes jatamansi

and 100 to 400 tonnes kutki. The export in the case year

1997/97 was 289 and 261 tonnes, respectively. The aver-

age value of the export, using the 1997/1998 price level,

for the two species is approximately 1.3 million USD,while the export value in the case year was around 1.4

million USD.

3.1.2. Export to China

As part of the central wholesaler and local trader sur-

veys, the export to China (Tibet) was investigated, Table

2. The direct trade with China is far smaller than trade

with India. Only a handful of traders are involved andonly N. scrophulariiflora rhizomes are traded; no direct

export of N. grandiflora rhizomes was recorded. Only

traders in the Eastern and Central Development Re-

gions are involved in direct trade with China. The price

obtained by Nepalese traders is comparable to that ob-

tained in India (Table 1). The annual export is estimated

at 18–57 tonnes with trade in 1997/1998 amounting to

approximately 47 tonnes at a value of USD 110,000.

3.1.3. Export to countries other than India and China

Data provided by the Department of Foreign Trade

was analysed to obtain information on the products ex-

ported to countries other than India and China. Samples

of unprocessed kutki rhizomes were exported to Japan

and the Netherlands; 10 tonnes of jatamansi marc, the

N. grandiflora rhizomes from which essential oil hasbeen extracted, was exported to Pakistan; and small

amounts of jatamansi oil (spikenard oil) were exported

to France, England, Pakistan, Spain, Germany and

South Korea. The total value of kutki exports was just

USD 11 while the value of jatamansi export was USD

29,000. The total value of all medicinal plant exports

to countries other than India and China in the case year

1997/1998 was just USD 247,000.

3.1.4. Estimating domestic industrial demand in Nepal

The only domestic industrial demand is from process-

ing of N. grandiflora rhizomes for essential oil. Besides

Table 2

Amount and value of annual export of unprocessed N. scrophulariiflora air-

district interviews

Development region Low estimatea High estimatea 1997/

Eastern 16 50 44

Central 2.1 6.5 2.8

Western 0 0 0

Mid-western 0 0 0

Far-western 0 0 0

Nepal 18.1 56.5 46.8

All amounts in tonnes, all values in �000 USD (68 Nepalese rupees/USD).a Derived from interviews with central wholesalers (n = 2) and local traderb Calculated as ((low + high estimates)/2)*av. selling price in Tibet in 1997

Nepal, at 2.3 ± 0.1 USD/kg.

the oil, this produces marc which is also exported. Based

on the N. grandiflora processor interviews (n = 9), the

annual demand for air-dried N. grandiflora rhizomes is

estimated at 10,000–246,000 kg with 201,000 kg pur-

chased by processors in the case year 1997/1998. Small

amounts of oil are sold in the domestic market and over-seas to countries such as Germany and England but the

dominant market is India. Assuming an average oil con-

tent of 1.5% and an average selling price of USD 140/kg

of oil, the value of production in 1997/1998 was approx-

imately USD 422,000. This gives a total value of N.

grandiflora exports in the case year of USD 1.1 million.

3.2. Estimating annual supply

The district level trade data estimates the size of the

entire annual harvest of the two species in Nepal. An

overview of the amounts of N. grandiflora and N. scro-

phulariiflora rhizomes entering trade based on the dis-

trict survey is presented in Table 3.

The figures in Table 3 indicate that the Eastern and

Central Development Regions are the most importantsupply areas for N. grandiflora rhizomes. The amounts

registered in the Western Development Region are very

low. Most supplies originate in the High Mountain

physiographic zone with only minor amounts from the

Middle Hills. Table 3 also indicates that the Eastern

Development Region is the dominant supply area for

N. scrophulariiflora rhizomes. The Central, Mid-western

and Far-western Development Regions provide approx-imately the same amounts. Registered supplies from the

Western Development Region are very low. Again, the

High Mountain physiographic zone is the most

important.

On basis of the district survey, the annual supply (RNepal9) of N. grandiflora air-dried rhizomes is estimated

at 70–330 tonnes, with a trade in 1997/1998 of 180 ton-

nes. The figures for N. scrophulariiflora are 175–770 ton-nes and 520 tonnes. The estimated annual consumption

figures (R Nepal10) are also provided; they are higher

than supply for N. grandiflora and lower for N.

scrophulariiflora.

dried rhizomes from Nepal to China based on central wholesaler and

1998 estimatea Av. export valueb 1997/1998 Export value

77 103

10 7

0 0

0 0

0 0

87 110

s (n = 4) dealing directly with China.

/1998. The latter is estimated, on the basis of the trader interviews in

Table 3

Annual amounts of unprocessed N. grandiflora and N. scrophulariiflora air-dried rhizomes entering trade in Nepal, based on district level survey

District survey N. grandiflora N. scrophulariiflora

Case districta Cell (no. of districts

in cell)

Low estimate High estimate 1997/1998 estimate Low estimate High estimate 1997/1998 estimate

Taplejung EDR High Mts. (3) 22 62 62 128 523 326

Dolakha CDR High Mts. (3) 16 116 48 10 34 22

Nuwakot CDR Middle Hills (9) 14 49 22 13 57 35

Mustang WDR High Mts. (3) 1 2 1 1 4 3

Humla MDR High Mts. (4) 12 54 32 10 70 66

Darchula FDR High Mts. (3) 9 44 16 15 78 65

R Nepal1 High mountains (16) 60 278 159 164 709 482

R Nepal2 Middle hills (39) 14 49 22 13 57 35

R Nepal3 Terai (20) 0 0 0 0 0 0

R Nepal4 EDR (16) 22 62 62 128 523 326

R Nepal5 CDR (19) 30 165 70 23 91 57

R Nepal6 WDR (16) 1 2 1 1 4 3

R Nepal7 MDR (15) 12 54 32 10 70 66

R Nepal8 FDR (9) 9 44 16 15 78 65

R Nepal9 Whole country (75) 73 327 181 176 765 517

R Nepal10b Whole country 111.5 682.5 490.3 119.4 462.5 307.4

All amounts in tonnes.a Includes only the districts where trade in the species was documented.b Calculated by summing the figures for export and domestic industrial demand.

Table 5

Estimate of annual amount (tonnes) and value (million USD) of

unprocessed air-dried rhizomes of N. grandiflora and kutki in trade in

1997/1998 based on origin of supplies and the Nepal national level

trade data

Supply country N. grandiflora Kutki

Amounta Valueb Amountc Valueb

Nepal 300 0.7 517 1.5

India 28–70 0.1–0.2 46–297 0.1–0.8

Bhutan 3–35 0.0–0.1 40–211 0.1–0.6

Global 345–390 0.8–0.9 663–957 1.9–2.7

a Amount for Nepal derived from combination of supply and con-

sumption estimates, see Section 4.b Calculated using the average regional wholesaler CIF buying prices

in India, Table 6.c Amount for Nepal using the annual supply estimate, see Section 4.

510 C.S. Olsen / Biological Conservation 125 (2005) 505–514

3.3. Estimating global supply of unprocessed jatamansi

and kutki rhizomes

Through interviews with regional wholesalers in In-

dia, the importance of different countries as supply

sources for rhizomes of the two species was investigated.

Only Nepal, Bhutan and India were mentioned as sup-ply countries. Of the 38 and 32 regional wholesalers in

India trading, respectively, N. grandiflora and kutki, 29

and 24 provided information on origin of supplies, Ta-

ble 4. Nepal is estimated to supply 82 ± 5% of N. gran-

diflora and 66 ± 12% of kutki rhizomes and is clearly the

main global supplier of both products; all involved

wholesalers obtain at least 70% of their N. grandiflora

supplies and 30% of kutki supplies from Nepal. Indiais the second largest supplier of both products followed

by Bhutan. The variation between wholesalers, as ex-

pressed in the min–max ranges, is due to differences in

locations.

Table 4

Summary of regional wholesalers� perception of origin of supplies of

unprocessed air-dried rhizomes of N. grandiflora (n = 29) and kutki

(n = 24)

Supply country N. grandiflora Kutkia

Mean ± s.d. Min–max Mean ± s.d. Min–max

Nepal 82 ± 5 70–90 66 ± 12 30–80

India 13 ± 5 5–20 19 ± 12 5–70

Bhutan 5 ± 4 0–15 14 ± 8 0–25

All figures in %.a Kutki in this table includes rhizomes of both N. scrophulariiflora

and P. kurrooa.

Using the information on origin of supplies in Table 4

and the supply and consumption estimates in Table 3 al-

low an estimation of the total global amount of unpro-

cessed air-dried N. grandiflora and kutki rhizomes,

Table 5. The trade in 1997/1998 is estimated at 350–

400 tonnes of N. grandiflora rhizomes with a CIF value

of USD 0.8–0.9 million, and 650–1000 tonnes of kutki

rhizomes CIF valued at USD 1.9–2.7 million. Forthe latter, the Indian estimate of 50–300 tonnes is a

maximum estimate of the CITES listed P. kurrooa trade

– subtracting the unknown amounts of N. scrophulariifl-

ora originating from Sikkim and possibly Garhwal

Himalaya would provide a more accurate P. kurrooa

estimate.

C.S. Olsen / Biological Conservation 125 (2005) 505–514 511

3.4. Wholesaler knowledge of trade related legislation

Regional wholesalers in India have by far the best

educational background of any of the actors involved

in the Himalayan plant trade: 84.9% has a university le-

vel education (Olsen and Bhattarai, 2005). Their knowl-edge of trade related legislation was investigated as part

of the regional wholesaler survey: 73.6% claimed knowl-

edge of the Indian Negative List of Exports, 71.7%

claimed knowledge of Nepali legislation (such as

requirement for harvesting permits and royalty pay-

ments), while only 34% claimed to be familiar with

CITES. A total of 24.5% found that legislation was

problematic, especially as it allowed for rent-seekingby police, customs and forest officials. Probing showed,

however, that knowledge of Nepali legislation and

CITES was often superficial. The reason may be that

the knowledge is not required as legislation is not en-

forced. As one wholesaler noted ‘‘. . . every banned item

is in trade, legislation has no impact in any sense’’. The

lack of legislative enforcement has previously been

noted as a problem with CITES implementation in theregion (Mulliken, 2000) and the problem with illegal ex-

ports from Nepal is widely recognised.

3.5. Financial importance to rural livelihoods

The average amount sold per harvester is

43.6 ± 7.0 kg N. grandiflora (n = 82) and 43.5 ± 6.9 kg

N. scrophulariiflora (n = 116). Using the harvesters�own-reported selling prices, Table 6, the average value

of rhizome sale in 1997/1998 was, respectively, USD

29.9 and USD 49.5 per harvester. Using the total har-

vests of, respectively, 300 tonnes and 517 tonnes indi-

cates that approximately 7000 and 12,000 harvesters

are involved, generating a total income of USD

800,000. Given an average annual household cash in-

come of small farm rural households in hills of USD162.9 (NHDP, 1998), and assuming one harvester per

household, the harvest of N. grandiflora and N. scro-

phulariiflora provides some 19,000 households from

18% to 30% of their annual cash income. If several

households pool their harvest before travelling and sell-

Table 6

Basic distributional statistics for selected own-reported prices (Nr/kg, 1997–

Price n Mean s.d

N. grandiflora

Harvester sale 95 46.7 10

Local trader purchase 32 60.5 11

Regional wholesaler purchase 37 152.5 11

N. scrophulariiflora

Harvester sale 127 77.4 12

Local trader purchase 48 87.9 15

Regional wholesaler purchase 32 191.5 12

ing to local traders, the number of households would be

higher and the percentage income lower. All rhizomes

are harvested in the wild (n = 21 harvester groups for

N. grandiflora and n = 26 for N. scrophulariiflora).

4. Discussion

4.1. Validity and reliability of findings

First, data needs to be considered in view of the two

assumptions made: that vegetation distribution, quality

and harvesting pressure is similar within cells, and that

all central wholesalers and local traders were interviewed.Second, the approach of relying on own-reported values

should be assessed. Consider these in turn:

� The first assumption means that supply of rhizomes

should be comparable between districts in the same

cell. This is not always the case, e.g., it could be

argued that tourism income opportunities in Manang

District leads to different land use patterns, influenc-ing the floristic composition and structure of the rhi-

zome producing alpine pastures and shrubs, than in

upper Gorkha District where there are fewer income

options. Harvesting pressure may thus also differ

within cells. Due to lack of case studies on medicinal

plant utilisation and management, it is not possible to

assess whether the assumption generally holds true.

� The second assumption implies that all relevantwholesalers and traders have been contacted and

interviewed. All located wholesalers and traders par-

ticipated in the interviews, but it may be that some

were not discovered. This is especially relevant for

the smaller and less visible local traders forming the

backbone of the district survey. There is no author-

ised list of wholesalers and traders. This indicates that

trader and wholesaler derived amounts may be con-servative estimates.

� Can own-reported values of trade prices and quanti-

ties be relied upon? Using agents� own-reported prices

has not previously been reported to be problematic in

studies of Himalayan plant trade. To examine this,

1998)

. Median Mode Min Max

.6 45.0 50.0 35.0 95.0

.0 60.0 65.0 40.0 80.0

.7 153.6 152.0 120.0 168.0

.1 80.0 80.0 60.0 105.0

.9 87.5 95.0 40.0 120.0

.9 200.0 200.0 164.8 208.0

512 C.S. Olsen / Biological Conservation 125 (2005) 505–514

the reported prices were first investigated by calculat-

ing basic distributional statistics, Table 6. These

national level findings indicate that each type of eco-

nomic agent provides consistent figures: the standard

deviation is small compared to the mean, the mean

and median values are very close as are the modaland median values. This indicates close clustering

around the mean and little skewness – this would

not be expected if harvesters and traders answered

randomly.

In order to investigate if answers could be systemati-

cally biased, the sale and purchase price of each species

in the same link of the marketing chain (harvesters sell-ing to local traders) was analysed. The one-way ANO-

VA tests show that price means, for both species, are

not equal with significance at 0.1% level. It may be that

harvesters are systematically understating the price ob-

tained from rhizome sale or that local traders are sys-

tematically overstating the price they have paid to

collectors.

The prices that regional wholesalers pay to centralwholesalers form the basis for calculating the value of

trade in this study. There is limited data with which to

assess the validity of these prices. However, it is noted

that the average export price for air-dried N. grandiflora

rhizomes to India of 2.2 ± 0.2 USD/kg (152.5 ± 11.7 Nr/

kg) and China of 2.3 ± 0.1 (158.7 ± 4.3) are comparable.

This may indicate that regional wholesalers have not

been systematically overstating their purchasing prices.The statistics in Table 6 indicate useful and consistent

figures. Some variation is expected within each type of

economic agent as expressed by the min–max range of

prices; previous studies have indicated price variations

across Nepal (Olsen and Helles, 1997).

Regarding own-reported quantities, studies have ar-

gued that there is a considerable illegal export of medic-

inal plants from Nepal to India (e.g., Malla et al., 1995).The official District Forest Office records for 1997/1998

(DoF, 1999) put national level harvest at 61,078 kg

kutki and 96,592 kg jatamansi. This corresponds to,

respectively, 12% and 53% of the district level estimates

provided in Table 3, indicating huge illegal harvest and

trade. This creates an incentive for traders and wholesal-

ers to underestimate traded quantities. Furthermore, in

the case year, export of unprocessed N. grandiflora rhi-zomes was illegal. This provides an additional incentive

for the exporting central wholesalers to underestimate

traded amounts. There is thus ample reason to regard

reported quantities as conservative estimates.

4.2. Comparing supply and consumption estimates

Based on the above, though both are likely to be toolow, it would be expected that the annual supply figure is

more accurate than the annual consumption figure, as

local traders have less incentive to understate traded

amounts than wholesalers. It would thus be expected

that the annual supply figure is higher than the con-

sumption figure. However, the opposite is found for

N. grandiflora. This is due to a combination of factors

leading to too low supply estimate and too high con-sumption estimate. The low supply estimate is caused

by failure to properly estimate the trade level for the

Western Development Region: the figure (for both spe-

cies) in Table 3 does not compare to available case stud-

ies. Olsen and Helles (1997) have estimated the annual

amount entering trade in Gorkha District (probably

the main supplying district in the Western Development

Region) at 25–84 tonnes N. grandiflora rhizomes and 7–18 tonnes N. scrophulariiflora compared to the total

WDR estimate here of, respectively, 1–2 and 1–4 tonnes.

The consumption estimate appears too high due to the

existence of the processing industry: the marc is sold

to India and abroad via the central wholesalers. There

may thus be double reporting of quantities. It may also

be that there is import of N. grandiflora rhizomes from

Tibet to Nepal (Mulliken, 2000) which would be in-cluded in the consumption estimate as Nepali rhizomes.

In conclusion, the valid trade figures for N. grandiflora

fall between the supply and consumption estimates in

Table 3 but are probably closest to the supply estimate.

A crude estimate is made of minimum 100 tonnes, max-

imum 500 tonnes, with around 300 tonnes traded in

1997/1998. There is only a small difference in supply

and consumption estimates due to storage and transportlosses along the marketing chain, e.g., central wholesal-

ers report average storage losses of 2.4 ± 1.9% for N.

grandiflora and no transport losses.

Both the supply and consumption estimates assume

that trade is not influenced by input from stocks. Use

of stocks would lead to inflated estimates. The assump-

tion is supported by low own-reported storage time

(e.g., central wholesalers� average storage time is2.6 ± 0.8 month for N. grandiflora and 2.6 ± 0.9 for N.

scrophulariiflora).

The global supply estimate in Table 5 does not in-

clude production in China and Pakistan and should thus

be considered conservative. There are no figures avail-

able on annual supply or consumption in these coun-

tries. There may be some export of N. grandiflora from

China to Nepal as noted above. China is apparently amajor consumer of N. scrophulariiflora (Olsen, 1998).

4.3. Conservation implications

The original Indian proposals to CITES for listing N.

grandiflora and P. kurrooa mentioned trade levels of,

respectively, 120 and 10–24 tonnes. This study estimates

annual trade levels at 100–500 and 50–300 tonnes. Dueto the distribution of P. kurrooa and N. scrophulariifl-

ora, the majority of the trade in kutki (175–700 tonnes)

C.S. Olsen / Biological Conservation 125 (2005) 505–514 513

is in the not-listed N. scrophulariiflora rather than the

listed P. kurrooa. This indicates that trade levels are

much higher than previously thought and that including

N. scrophulariiflora in Appendix II needs to be given ur-

gent attention. The following should be considered:

� There is no detailed information on the distribution

of the two species, e.g., coverage of the species in

existing protected area networks across the Himala-

yan states. Nor is it clear how effective protection is

in protected areas. There is no information available

on the stock of resources or sustainable harvesting

rates. The apparently high trade levels, and the possi-

bly rising demand, underlines the urgent necessity ofundertaking detailed species level assessments of con-

servation status for both species and establishing sus-

tainable harvest rates. Recent research (Ghimire

et al., 2005) indicates that sustainable commercial

harvest of N. scrophulariiflora may be feasible, while

N. grandiflora appears very sensitive to harvest. The

status survey should include an in-depth investigation

of the causes of population decline, e.g., what is therole and importance of habitat destruction compared

to commercial harvest and trade? Such knowledge is

required to design and implement effective policies

coping with the right threats.

� Due to the financial importance of the species to rural

harvesters, it is suggested that the question of inclu-

sion of N. scrophulariiflora be addressed using the

deliberation-guiding version of the precautionaryprinciple (Dickson, 2000), i.e., in the face of uncertain

conservation data predefined definite actions, such as

simply banning harvest and trade, are not likely to

provide the best solution. The analysis providing

the basis for decision of listing must explicitly include

discussion of both conservationist and social con-

cerns, and must attempt to identify all processes pos-

ing threat to the species.

The estimated high levels of trade also show that

most trade, domestically in Nepal and between range

countries and India, takes place illegally. There is no

doubt that large scale international trade is conducted

outside the controls of CITES, especially between Nepal

and India and to some degree across the Sino-Nepalese

border. Official Nepalese CITES annual export data for1997 and 1998, accessed using the CITES trade database

(UNEP-WCMC, 2005), show no N. grandiflora export

(nor any P. kurrooa export). And, as mentioned above,

the official District Forest Office records (DoF, 1999)

puts national level harvest at just 12% and 53% of the

national harvest levels estimated in Table 3 for N. gran-

diflora and N. scrophulariiflora, respectively. This clearly

shows that official trade monitoring at Nepal�s bordersis very poor. A more effective implementation of CITES

is required.

As Nepal is the major supplier of rhizomes of both

species (and of the product kutki), trade interventions

in Nepal could have significant impact on conservation

of the species (and P. kurrooa) in other Himalayan range

states. For instance, if supplies from Nepal decrease due

to enforcement of the existent ban on export of unpro-cessed N. grandiflora rhizomes or more effective imple-

mentation of CITES, this will lead to increasing prices

and thus increasing harvesting pressure in neighbouring

countries. Isolated national initiatives may have nega-

tive externalities. This and use of the deliberation-

guiding version of the precautionary principle suggests

that Nepal and the other range states should emphasise

regional co-operation on commercial plant conservationissues rather than the national approach currently being

implemented.

5. Conclusions

Even though much of the trade in N. grandiflora and

N. scrophulariiflora is illegal, it is possible to investigatesuch trade at the species level. Trader, wholesaler and

harvester own-reported data should be treated with care

but it appears that data is reliable and that validity is

acceptable as conservative estimates are derived. In gen-

eral, data derived from local trader interviews have

higher validity than data obtained through wholesaler

interviews as the former have fewer incentives to under-

estimate traded amounts. By combining questions onvolume and origin of supplies in regional wholesaler

interviews, and understanding the composition of traded

products, it was possible to establish insight into the

trade of a CITES listed species from findings on trade

in a similar not-listed species.

However, while such trade studies are possible, they

are also time consuming and costly. The only feasible

way to obtain reliable annual trade figures, that can pro-vide useful input to conservation decisions, is to signifi-

cantly improve official trade monitoring.

Trade data revealed much higher levels of trade than

previously reported. This emphasises the need for sus-

tainable management of wild plant populations of the

two species and policies to support such management.

It is argued that trade data and household level informa-

tion is important in order to design effective conserva-tion policies and interventions. Without such data,

conservation measures may prove inefficient. Further

studies on the conservation status of the species are rec-

ommended, including determining distribution and cov-

erage in existing protected area networks, and main

threat factors.

Conservation of the species should be based on a re-

gional rather than a national approach. As Nepal is themain supplier of rhizomes of both species, that are

traded mainly to India and harvested exclusively in the

514 C.S. Olsen / Biological Conservation 125 (2005) 505–514

wild, strict and effective domestic measures may have

serious consequences for harvesting of resources in

neighbouring countries. As most trade taking place is

illegal across national borders, improved official trade

monitoring by governments is required.

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to the many harvesters, traders and

wholesalers who took time to participate in the study.

Nirmal Bhattarai was invaluable during data collection

and Malene Hall is thanked for her contributions to

data handling. An anonymous reviewer provided highlyuseful comments. The study was financed by the Minis-

try of Foreign Affairs and the Royal Veterinary and

Agricultural University, Denmark.

References

Brummitt, R.K., 1992. Vascular Plant Families and Genera. Royal

Botanical Gardens, Kew.

Cunningham, A.B., 1997. The ‘‘Top 50’’ listings and the medicinal

plants action plan. Medicinal Plant Conservation 3, 5–7.

Dhar, U., Rawal, R.S., Upreti, J., 2000. Setting priorities for

conservation of medicinal plants – a case study in the Indian

Himalaya. Biological Conservation 95, 57–65.

Dickson, B., 2000. Precaution at the heart of CITES? In: Hutton, J.,

Dickson, B. (Eds.), Endangered Species – Threatened Convention.

Earthscan Publications Ltd, London, pp. 38–46.

DoF, 1999. Annual Report – F.Y. 2054/55. Department of Forest,

Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation, Kathmandu.

Farooquee, N.A., Saxena, K.G., 1996. Conservation and utilisation of

medicinal plants in high hills of the central Himalayas. Environ-

mental Conservation 23, 75–80.

Ghimire, S.K., McKey, D., Aumeeruddy-Thomas, Y., 2005. Conser-

vation of Himalayan medicinal plants: harvesting patterns and

ecology of two threatened species, Nardostachys grandiflora DC.

and Neopicrorhiza scrophulariiflora (Pennell) Hong. Biological

Conservation 124, 463–475.

Hertog, W.H., Wiersum, K.F., 2000. Timur (Zanthoxylum armatum)

production in Nepal: dynamics in non-timber forest resource

management. Mountain Research and Development 20, 136–145.

Holley, J., Cherla, K., 1998. The medicinal plants sector in India. The

International Development Research Center, South Asia Regional

Office, Medicinal and Aromatic Plants Programme in Asia, Delhi.

Hong, D.Y., 1984. Taxonomy and evolution of the Veroniceae

(Scrophulariaceae) with special reference to palynology. Opera

Botanica 75, 5–60.

ISRSC. 2001. District development profile of Nepal. Informal Sector

Research and Study Centre, Kathmandu.

Jacob, I., Jacob, W. (Eds.), 1993. The Healing Past: Pharmaceuticals in

the Biblical and Rabbinic World. E.J. Brill, Leiden.

Kala, C.P., 2000. Status and conservation of rare and endangered

medicinal plants in the Indian trans-Himalaya. Biological Conser-

vation 93, 371–379.

Larsen, H.O., 2002. Commercial medicinal plant extraction in the hills

of Nepal: local management systems and sustainability. Environ-

mental Management 29, 88–101.

Larsen, H.O., Olsen, C.S., Boon, T.E., 2000. The non-timber forest

policy process in Nepal: actors, objectives and power. Forest Policy

and Economics 1, 267–281.

Lillesø, J.-P.B., Shrestha, T.B., Dhakal, L.P., Nayaju, R.P., Tamrakar,

P.R., Shrestha, R., 2001. The map of potential vegetation of Nepal

– a forestry/agro-ecological/biodiversity classification system.

Draft. Natural Resource Management Sector Assistance Program,

Kathmandu.

Malla, S.B., Shakya, P.R., Rajbhandari, K.R., Bhattarai, N.K.,

Subedi, M.N., 1995. Minor forest products of Nepal: general

status and trade. FRIS Project Paper No. 4, Forest Resource

Information System Project, HMGN/FINNIDA, Kathmandu.

Manandhar, N.P., 1980. Medicinal Plants of Nepali Himalaya. Ratna

Pustak Bhandar, Kathmandu.

Mulliken, T.A., 2000. Implementing CITES for Himalayan medicinal

plants Nardostachys grandiflora and Picrorhiza kurrooa. TRAFFIC

Bulletin 18, 63–72.

Murty, T.K., 1993. Minor Forest Products of India. Oxford and IBH

Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd., Delhi.

Nadeem, M., Palni, L.M.S., Purohit, A.N., Pandey, H., Nandi, S.K.,

2000. Propagation and conservation of Podophyllum hexandrum

Royle: an important medicinal herb. Biological Conservation 92,

121–129.

NHDP, 1998. Nepal Human Development Report 1998. Nepal South

Asia Centre, Kathmandu.

Olsen, C.S., 1998. The trade in medicinal and aromatic plants from

central Nepal to northern India. Economic Botany 52, 279–292.

Olsen, C.S., Bhattarai, N.K., 2005. A typology of economic agents in

the Himalayan plant trade. Mountain Research and Development

25, 37–43.

Olsen, C.S., Helles, F., 1997. Medicinal plants, markets and margins in

the Nepal Himalaya: Trouble in Paradise. Mountain Research and

Development 17, 363–374.

Olsen, C.S., Larsen, H.O., 2003. Alpine medicinal plant trade and

Himalayan mountain livelihood strategies. Geographical Journal

169, 243–254.

Polunin, O., Stainton, A., 1984. Flowers of the Himalaya. Oxford

University Press, Delhi.

Rai, L.K., Prasad, P., Sharma, E., 2000. Conservation threats to some

important medicinal plants of the Sikkim Himalaya. Biological

Conservation 93, 27–33.

Shrestha, T.B., Joshi, R.M., 1996. Rare, endemic and endangered

plants of Nepal. WWF Nepal Program, Kathmandu.

Smit, F., 2000. Picrorhiza scrophulariiflora, from traditional use to

immunomodulatory activity. Faculteit Farmacie, Universiteit Utr-

echt, Utrecht.

Tandon. V., Bhattarai, N.K., Karki, M. (Eds.), 2001. Conservation

assessment and management plan workshop report: selected

medicinal plants species of Nepal. Medicinal and Aromatic Plants

Program in Asia (MAPPA), International Development Research

Centre (IDRC) and Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation,

Kathmandu.

UNEP-WCMC, 2005. CITES trade database, www.cites.org/eng/

resources/trade.shtml (accessed 07.03.2005).

Ved, D.K., Tandon, V., 1998. CAMP Report for High Altitude

Medicinal Plants of Jammu-Kashmir and Himachal Pradesh.

Foundation for the Revitalisation of Local Health Traditions,

Bangalore.