Of the True Professional...

Transcript of Of the True Professional...

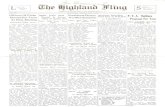

August 7, 1934 New Zealand Law Journal.

” A rmzn who regards the Bar merely as a trade or business and does not understand that it is also a profes- sional community with public ideals misses the heart of the thing.”

-MR. J. E. SINGLETON, K.C., in Conduct at the Bar.

Vol. x. Tuesday, August 7, 1934 No. 14

Of the True Professional Spirit.

I N the course of delivering the Maudsley Memorial

Lecture before the Royal Medico-Psychological Society in London recently, Lord Macmillan said that all would agree that the practice of a calling of any sort had a decisive and pervasive influence on a man’s whole mental outlook :

“His habits are controlled, his thoughts canalised, his prejudices formed by the profession he practises; even his place of residence may be dictated by his vocation-as witness the Temple, where studious lawyers have their haunts. From the earliest times the practitioners of a particular art have always shown a tendency to draw apart and constitute a separate fraternity with their own ceremonial rites and shib- boleths. Nowadays the barriers are broken down and men of all careers mix with each other. But certain typical attri- butes will always remain to lend colour and interest to social life. In these days of exaggerated and explosive nationalism it is important to foster all those bonds which tend to unite men of common pursuits, irrespective of geographical boundaries. The professions exercise a broad and catholic influence which traverse national frontiers unimpeded by tariffs and quotas and, by promoting free trade in all bene- ficial discoveries, advance the welfare of humanity at large.”

In the case of a lawyer, this influence arises from an understanding and proper regard for the true professional spirit of his calling, which is as important a part of his mental equipment as a knowledge of law. “ A pride in his professional traditions and a desire to uphold and maintain these traditions for those who come after,” as the Solicitor-General, Sir Donald Somervell, said recently at the Lord Mayor’s Banquet to the Judges, constitute-with a love for his profession-the chief characterisics of a true lawyer. These are made evident day by day in the Courts by his practice and example which, in themselves, in Lord Tomlin’s words, “ cannot fail to be of value to the community as a whole.”

These pleasing features of professional character are emphasized in the course of two lectures delivered last year in the Inner Temple, under the Chairmanship of Lord Atkin, by Mr. J. E. Singleton, K.C., at the invita- tion of the Council of Legal Education. Now published in a booklet, Conduct at the Bar, they deserve careful study by student and practitioner alike. In addition to a study of barristerial traditions, Mr. Singleton

makes some practical observations on various phases of professional work-with regard to the public generally ; with regard to the lay client ; with regard to other members of the profession ; and on the duty to the Court. He reminds us that, speaking generally, the work of a solicitor is a work of prepara- tion, while that of a barrister is that of presentation ; and that each is in a very real sense dependent on the other : relatively, between them “ there is a diversity of function rather than of status.” Naturally, in New Zealand this observation is not of general application ; but, in cases where there is a distinction between the lay client’s solicitor and his Counsel, Mr. Singleton’s advice applies. It is, of course, proper practice that the lay client does not see Counsel except in his solicitor’s presence. This does not mean that the lay client should never see Counsel. Mr. Singleton gives this advice :

“I conceive it to be wise and good practice that the lay client should always be seen by Counsel before a case comes on for trial. It may be that he understands little about it-- perhaps he is not to be called as a witness or is only a witnesa on formal matters-but it is his case and he likes to see Counsel and to know that his Counsel is taking a personal interest in the matter.

“ Litigants regard barristers as expensive luxuries ; if the case is lost they are apt to say, ‘I might just as well have poured my money down the gutter,’ while if they win they are equally likely to say, ‘It was a certainty and my Counsel did nothing, but I had to pay him all the same.’ If they can add to this, ‘ I never saw him until we went into Court,’ they give the impression that Counsel took no interest in the matter, for they know nothing of the hours spent in getting up a case. I repeat that a consultation beforehand with the lay client is desirable in everyone’s interest.”

Lord Tomlin once said : “ It is better to be wrong sometimes than never to have a mind of your own ” ; but Mr. Singleton’s advice is not so far-reaching. As regarda opinions, he would have none of the Counsel who marshals a series of decisions pro, and then a series contra, and leaves it to the solicitor or the client to decide on their relative merits. He says :

“An opinion ought to be as definite as possible-one remembers the remark about an opinion ‘ It is your opinion I asked for and not your doubts.’ But having given his opinion, Counsel is perfectly right in a doubtful case to point out that there is another possible view and that the state of the authorities is such that the case may well not end in the Court of first instance.”

As the lecturer remarks, a member of the Bar loses nothing in the long run by advising caution and con- sideration of the cost. Where there appears to be a risk, he should place himself as far as possible in the position of the lay client, and consider what he would do in like circumstances and advise accordingly. This is reminiscent of the advice given last year by Sir Thomas. Inskip, K.C., Attorney-General :

“Until you have acquired the habit, with sympathy and with patience and with thoroughness, of putting yourself into the position which the client occupies, you will not have really prepared yourself for being a sound adviser.”

But, says Mr. Singleton, “ if the client, advised of the risk, desires the case to be fought to a finish, it is Counsel’s duty to fight it for him and to use every legitimate effort to bring about success.”

Clients are seldom satisfied with settlements, and it is important they should have the whole position placed before them. Mr. Singleton points out it is the client’s litigation, and it is he who is paying ; and Counsel is briefed to conduct the case. He adds :

“If there iS a SUggeStiOn of a settlement and Counsel's views are sought it is his duty to give them according to the best of his ability. He ought at the same time to point out

New Zealand Law Journal. August 7, 1934

that, while his advice is so and so, it is for the client to say whether there is to be a settlement or not.”

Counsel engaged in an action (in which, in New Zea- land, he is not also solicitor ; and he who is practising as a barrister only) should not interview witnesses, other than the parties and experts or professional wit- nesses who are instructing Counsel. The EngIish Bar Council recognizes there may be exceptions to this rule, but it is not possible to formulate the circumstances in which such a departure from the practice is per- missible : 1934 Annual Practice, 2616. The solicitor’s duty is to prepare and put before Counsel the material on which the case is to be fought. Mr. Singleton has some interesting observations on the proper exercise of Counsel’s discretion as to seeing witnesses in certain circumstances, which he outlines.

Counsel should not depart from the general principle that he ought not to accept a brief unless there is a reasonable probability of his being able to take it. The lecturer points out that there is an honourable tradition of the English Bar that even a man who may be busy with different cases “ if he is called upon to defend the meanest criminal charged with a crime, is bound to give his personal attention to that work, odious and unre- munerative as it may be, to the exclusion of all other business coming his way,>’ to use the words of Sir John Simon when addressing the Canadian Bar Association in September, 1931. Mr. Singleton devotes some consideration to the spirit in which that duty should be discharged, and concludes :

“ I am afraid there are occasions when the full measure of this duty is not observed; it cannot be too strongly emphasized that, when cases clash, it is the defence in a criminal case that ought not to be left.”

Already under a heavy debt to Mr. Singleton’s first lecture, we forbear to quote from his second excellent summary of Counsel’s duty to the Court. He refers to that confidence of the Bench in the Bar on which the whole foundation and structure of the administration of British justice depends ; to behaviour in Court ; the handling of witnesses’ cross-examination, in par- ticular as to credit, and re-examination ; the concise statement of propositions of law, and the citation of authorities in the proper form. He considers at length what Lord Macmillan has called “ the supreme test problem in the ethics of advocacy”-when a member of the Bar is faced with a difficulty in that knowledge comes to him which makes him doubt his cIient, or when a confession to the advocate is made by an accused person.

In the section devoted to “ Conduct at the Bar with regard to other members,” Mr. Singleton treats of the close relationship and happy equality of barristers, as of newly-called juniors with distinguished leaders. He tells that on the Northern Circuit the junior is sworn in on undertaking his office in the Bar Mess, and the old form contains these words,

“ and the condition of your bond is that you do always uphold the rights and privileges of the stuffs and do ever watch and guard against the vile aspirations of the silks.”

The helpfulness which springs from this recognition of fraternity and equality is next considered :

“One of the greatest pleasures in connection with life at the Bar is to be found in the help which is readily given by one member of the Bar to another. At the Bar, as in other professions, many lasting friendships are made, but I doubt, whether in any other profession there is found so great a measure of readiness to give help and advice. Every member of the Bar, be he young or old, finds himself from time to time perplexed by difficulties. I refer not so much to diffi- culties of the law 8s to matters in which it may appear that

the duty to the client and the duty to the Court conflict; for example, your client may wish you to take a line which you Chink you ought not to take. Or again, questions may arise affecting another member of the Bar. On all such occasions it is well to remember that the services of any member of the Bar, however eminent, are at the disposal of any other member of the Bar. Two minds are always better than one, and, though the member of the Bar immediately concerned may have a clear view as to what his duty is, it is often a boon to him that he may go to any senior member of the Bar and have the benefit of his view ; and I believe it to be the fact, that all members of the Bar are ready to cast anything else aside in order to advise one of their number who finds himself confronted by a difficulty, and that they regard this as an essential feature of the Bar of England.”

Enough has been said to indicate that members of the profession, if they do find anything in Conduct at the Bar which they did not know (or at least ought to have known, or having known, have forgotten) will derive much pleasure from a perusal of Mr. Singleton’s wise and high-minded advice, coming as it does as the fruit of a large experience and ripe wisdom. He concludes his lectures, which are now published by order of the Masters of the Bench of the Inner Temple, with this fine reminder :

“ If you remember always that you belong to a great pro- fession which has a far-reaching influence on the welfare of the country, you will not fail. Remember the exampIe which has been set for centuries ; remember you are part of a great legal system which is the admiration of the world ; and make up your minds that no hope of immediate gain shall lead you to depart from the traditions of the Bar.

“ So doing, you are not only members of the Bar, but you are at the same time fulfilling a duty to the public and to the State.”

A further recommendation for Conduct at the Bar, to which Mr. A. M. Langdon, K.C., Director of Legal Education, provides an Introduction, is that the pro- ceeds of its sale are to be devoted to the Barristers’ Benevolent Association of England.

Summary of Recent Judgments. COURT OF APPEAL

Wellington. I 1934.

July 2, 18. MOIR v. WHITE. Myers, C. J. Reed, J. Johnston, J. 1

Arbitration-“ Any question arising in any cause or matter “- Reference by Judge under s. 14 of Arbitration Act, 1908, of all Questions in Dispute in Action other than Matters of Law or Issue of Fraud to Special Referee-Whether justified- Arbitration Act, 1908, s. 14.

Appeal from an order made by Mr. Justice Ostler that all questions in dispute in the action other than matters of law or the issue of fraud be referred to a special referee.

Goldstine and J. N. Wilson, for the appellant ; Leary, for the respondent.

Held, That the power given by s. 14 of the Arbitration Act, 1908, to the Court or a Judge to “ refer any question arising in

any cause or matter (other than a criminal proceeding by the Crown) for inquiry or report to any official or special referee ” is limited to the reference of specific questions which must necessarily be decided in the cause or matter and does not justify a reference of “ all questions in dispute in an action other than matters of law or the issue of fraud,” as that may involve the reference of questions that it may prove unnecessary to decide.

August 7, 1934 New Zealand Law Journal.

Weed v. Ward, (1889) 40 Ch. D. 555, applied. Cruikshank v. Floating Swimming Baths Co., (1876) 1 C.P.D.

260, and Hurlbatt v. Barnett and Co., [1893] 1 Q.B. 77, dis- cussed.

Solicitors : Goldstine, O’Donnell, and Wilson, Auckland, for the appellant; Bamford, Brown, and Leary, Auckland, for the respondent.

Case Annotation : Weeds. Ward, E. $ E. Digest, Vol. 2, p. 613, para. 2440 ; Cm&hank vu. Floating Swimming Baths Co., ibid. p. 631, para. 2577 ; Hurlbatt v. Barnett, ibid. p. 623, para. 2522.

NOTE :-For the Arbitration Act, 1908, see THE REPRINT OF THE PUBLIC ACTS OF NEW ZEALAND, 1908-1931, Vol. 1, title Arbitration, p. 346.

COURT OF APPEAL Wellington.

June 21 ; July 18. Myers, C. J. Reed, J. Ostler, J. Johnston, J.

i

i

COMMISSIONER OF STAMP DUTIES v. A. 0. SCHULTZ.

COMMISSIONER OF STAMP DUTIES v. F. W. SCHULTZ.

Revenue-Stamp Duty-Will-Testator devising Lands to Sons- Condition that each Devisee executes a Mortgage to Trustees of Will for Sum either fixed by Testator or ascertainable pur- suant to Directions in Will-Whether Transfers subject to Conveyance Duty upon Amount of Mortgages given by Devisees -“ Extent to which he ” [the Devisee] “ is so entitled ” under the Will-Stamp Duties Act, 1923, s. 81 (d).

Appeals from the judgment of Blair, J., reported ante. p. 133. Section 81 (d) of the Stamp Duties Act, 1923, exempts from conveyance duty a conveyance by a trustee to a devisee of property to which such devisee is entitled under the will “ to the extent to which he is so entitled.”

A testator devised parcels of land to sons upon condition that each devisee executed a mortgage in favour of the trustees of the will for a sum either fixed by the test&or or ascertainable pur- suant to his directions in the will in that behalf. The trustees executed memoranda of transfer accordingly to the devisees upon their executing memoranda of mortgage in accordance with the condition expressed in the will.

C. H. Taylor, for the appellant ; Cullinane, for the respondents.

Held, by the Court of Appeal (Myers, C.J., Reed and Ostler, JJ., Johnston, J., dissenting), That each transfer was subject to con- veyance duty upon the amount of the mortgage given by the devisee, on the ground that the devisee to the extent of the amount secured by the mortgage which he executed was a purchaser, and, therefore, to that extent he was not entitled under the will so as to come within the exemption provided by s. 81 (d) of the Stamp Duties Act, 1923.

Sutherland v. Minister of Stamp Duties, [1921] N.Z.L.R. 154, applied.

Thompson v. Commissioner of Stamp Duties, [I9261 N.Z.L.R. 872, distinguished.

McIiraith v. Commissioner of Stamp Duties, (1906) 25 N.Z.L.R. 949, discussed.

Held, by Johnston, J., dissenting, 1. That the common fea- ture about different groups of conveyances exempted from conveyance duty is that the exemption is given by virtue of the nature of the transaction, irrespective of the question of consideration.

2. That the reason of the exemption under s. 81 (d) is because of the levies made under the Death Duties Act in respect of the property transferred.

3. That the language used in an exemption clause of a statute must be understood in a popular sense and, so interpreted, the exemption in s. 81 (d) cannot permit a construction that splits the transfer so that one part, is within and the other outside the exemption.

4. That when the Legislature intends to limit exemption from duty to transfers to derisees where there is no valuable consideration, it has expressed such intention clearly, as in the proviso to the Seventh Schedule of the Finance Act, 1915.

The true test therefore is : Was the transfer pursuant to the testator’s direction in his will or not (irrespective of considera- tion) ; not did the devisee give consideration, although the trans- fer was pursuant to the will ?

The test in In re Beverley, Watson v. Watson, [I9011 1 Ch. 681, as to appropriations applied to directions (equivalent to appro- priation) by testator.

McIlraith v. Commissioner of Stamp Duties, (1906) 25 N.Z.L.R. 949, and Thompson v. Commissioner of Stamp Duties, [1926] N.Z.L.R. 872, applied.

Sutherland v. Minister of Stamp Duties, [I9211 N.Z.L.R. 154, Hammond v. Minister of Stamp Duties, [1918] N.Z.L.R. 968, and Watt v. Commissioner of Stamps, (1900) 19 N.Z.L.R. 123, discussed.

The Court expressed no opinion as to whether the Commis- sioner of Stamp Duties would be justified under s. 40 of the Stamp Duties Act, 1923, in assessing conveyance duty on the amount of a mortgage existing upon devised land when trans- ferred by the trustees to the devisee, as the question did not directly arise on these appeals.

Solicitors : Crown Law Office, Wellington, for the appellant ; Kelly and Cullinane, Feilding, for the respondents.

Case Annotation: In re Beverly, Watson v. Watson, E. & E. Digest, Vol. 24, p, 593, para. 6268.

NOTE :-For the Stamp Duties Act, 1923, see THE REPRINT OF THE PUBLIC ACTS OF NEW ZEALAND, 1908-1931, Vol. 7, title Public Revenue and Expenditure, p. 402.

COURT OF APPEAL Wellington.

1934. June 27, 28.

Myers, C. J. Reed, J. Ostler, J. Johnston, J.

t THE KING v. HOUSTON.

Criminal Law-Theft-Moneys received on Account of Another- Proper Entries in Secret Account not intended for Creditor- False Stock-sheets and false Entries in Balance-sheets sup- plied to Creditor-Not “proper entries in a Debtor and Creditor Account “-Crimes Act, 1908, s. 242.

Motion for leave to appeal on the ground that the learned trial Judge refused to reserve the following question of law :-

“ Whether under the arrangement between the prisoner and John Burns 8: Co., Ltd., the money received by the prisoner on the sale of a machine formed an item in a debtor and creditor account between the parties, and the said John Burns & Co., Ltd., relied only on the personal liability of the prisoner in respect thereof within the terms of the proviso to s. 242 of the Crimes Act, 1908 ? ”

Bunny and Gillespie, for the prisoner ; Solicitor-General, Cornish, for the Crown, was not called upon.

Held, That where a person receives goods on terms requiring him to account for or pay the proceeds of their sale to another, he does not come within the proviso to s. 242 of the Crimes Act,, 1908, as having “ made proper entries in a debtor and creditor account between the person receiving the moneys and the person to whom he is to account for or pay the same,” when he enters the sums redeived by him in accounts kept by himself and not intended for the eye of his creditor but, as between himself and his creditor, he fraudulently conceals the fact that he has sold soods by sending his creditor stock-sheets showing these goods %re still in stock, and by making a false entry of the amount of his stock in a balance-sheet prepared for that creditor.

R. v. Kirk, (1901 120 N.Z.L.R. 463, referred to.

192 New Zealand Law Journal. August 7, 1934

Solicitors : Bunny and Barrett, Wellington, for the prisoner ; Crown Law Office, Wellington, for the Crown.

NOTE :-For the Crimes Act, 1908, 888 THE REPRINT OF THE PUBLIC ACTS OF NEW ZEALAND, 19081931, Vol. 2, title Criminal Law, p. 182.

SUPREME COT~T \

ESCOTT v. THOMAS.

Practice-Interim Injunction-Ex Parte Application-Material Facts-Duty of Solicitor to bring Defence and Facts on which it is based before the Court.

Motion on behalf of a defendant to dissolve an interim injunc- tion obtained ex parte by plaintiff in the action, on the ground that in his application for the injunction the plaintiff failed to disclose to the Court material facts which might have affected its decision in granting or refusing the injunction.

T. P. McCarthy, in support ; C. J. O’Regan, to oppose.

Held, That, in applying ex parte for an interim injunction it is not for the solicitor preparing the papers to decide whether a defenoe founded on facts is a good defence or not : his duty is fully to disclose to the Court the defenoe to his action if he knows it, and the facts on which it is based, so that the Court can judge whether they are material or not.

Solicitors : P. J. O’Regan and Son, Wellington, for the plaintiff ; Lelcester, Jowett, and Rainey, Wellington, for the defendant.

SUPREME COURT ) Auckland.

1934.

I June 29 ; July 17. F&T, J.

IN RE N., A DEBTOR.

Mortgagors and Tenants Relief-Bankruptcy Petition-Remls- sion of Debtor’s Arrears and Reduction of Interest by Mort- gagee prior to filing of Petition without Application for Relief having been made-Suspension of Bankruptcy Proceedlngs- Mortgagors and Tenants Relief Act, 1933, s. l&Bankruptcy Act, 1908, s. 40.

Creditors petition to have a debtor adjudged a bankrupt.

In opposing an order for adjudication the debtor relied, inter c&a, upon the provisions of s. 16 of the Mortgagors and Tenants Relief Act, 1933. He had made no application for relief under the Act, but the principal creditor, the mortgagee of the debtor’s farm property, had remitted ;E1,200 due to him, and, in the two years prior to the filing of the bankruptcy petition by another creditor, had reduced the rate of interest under the mortgage from 6 per cent. to less than 3 per cent. The debtor claimed that the position was the same as if he had applied for relief, and an order had been made by consent to that effect.

Rudd, for the petitioning creditor ; O’Neill, for the debtor.

Held, That, in cases similar to the present, the Mortgagors and Tenants Relief Act suspends the rights in bankruptcy of creditors when relief has been applied for, to enable the debtor, who has presumably committed an act of bankruptcy to continue in business, and-as all the creditors except the petitioner believed in 1932 and 1933, and still believed, that the debtor might in the future be able to meet his liabilities, at least in part, and should be allowed to carry on his farming business-if an application for relief to the Supreme Court were necessary for leave to proceed on the bankruptcy petition it was unlikely that it would be granted. Under these circumstances there was power under s. 40 of the Bankruptcy Act, 1908, to dismiss the petition on that ground.

The bankruptcy proceedings were suspended for twelve months on terms.

Solicitors : L. F. Rudd, Auckland, agent for Miller, Poulgraln, and Garland, Themes, for the petitioning creditor ; C. N. O’Neill, Paeroa, for the debtor.

NOTE :-For the Bankruptcy Act, 1908, see THE REPRINT OF THE PUBLIC ACTS OF NEW ZEALAND, 1908-1931, Vol. 1, title Bankruptcy, p. 466; for the Mortgagors and Tenants Relief Act, 1933, see Kavanagh and Ball’s The New Rent and Interest Reductions and Mortgage Legislation, 2nd Ed., p.1.

COURT OF APPEAL Wellington.

1934. I 1 June 28 ; July 18., PUTARURU PINE AND PULP CO.,

Reed, J. I

(N.Z.), LTD. v. MacCULLOCH.

Ostler. J. Johnkon, J. !

Company-Remuneration of Directors-Article authorizing Pay- ment to Directors as Remuneration of such Sums as Company might fix at General Meeting-Illusory Promise-Effeot of Vote of Remuneration to Directors for past Services--Whether Inference of implied Contract-Whether such Vote valid where Company has made no Profit.

Service by a director of a company raises no implication that the service will be paid for; to recover remuneration a director must show a contract, otherwise the fees are in the nature of a gratuity voted.

Hutton v. West Cork Railway Co., (1883) 23 Ch. D. 654, and In re George Newman and Co., [I8951 1 Ch. 674, applied.

The possibility of some payment accompanied by words that showed that the promisor was to have a discretion or option as to whether a director was paid anything or not, implied in the following article :-

“ The directors shall be paid out of the funds of the company, by way of remuneration for their services, such sum or sums as the company may from time to time fix at a general meeting, and such remuneration shall be divided amongst them in such proportions and manner as the directors may determine,”

is an illusory promise upon which no contract can be based.

In re Lelcester Club and County Racecourse Co., Ex parte Cannon, (1885) 30 Ch. D. 629, and Loftus v. Roberts, (1902) 18 T.L.R. 532, applied.

The vote by the shareholders of a sum of money as remunera- tion for past services, which, in a case other than that of a director, would support an inference that there was an implied contract that such services would be reasonably remunerated, and that the sum voted was either such reasonable remunera- tion or was evidence to fix the amount of remuneration, has no such effect in the case of a director.

Accordingly, the mere vote of a gratuity to a director for past services, where there is no contract, gives a director no cause of action, although, acting on such resolution, if valid, directors would be justified in paying themselves the amount of the gratuity so voted.

In re New British Iron Co., Ex parte Beckwith, [1898] 1 Ch. 324 ; In re Anglo-Austrian Printing and Publishing Union (Isaac’s case), [1892] 2 Ch. 158, and In re Al Biscuit Co., [1899] W.N. 115, distinguished.

Semble, where the vote was based upon an incorrect balance- sheet showing a profit, but since the inception of the company there had been no profits out of which a gratuity could be paid, the vote was uZ&a wires of the shareholders, as remuneration to directors for past services cannot be paid out of capital, in the absence of a definite and valid contract w-ith them for pay- ment for their services.

Counsel : Johnstone, K.C., with him R. P. Hunt, for the appel- lant ; Towle, for the respondent.

Solicitors: R. P. Hunt, Auckland, for the appellant ; Towle and Cooper, Auckland, for the respondent.

Case Annotation : Hutton 2). West Cork Railway Co., E. & E. Digest, Vol. 9, p. 614, para. 4080 ; In re ffeorge Newman and Co., ibid. p. 173, para. 1102 ; In re Leicester Club and County Race- cowree Co., Ex parte Cannon, ibid. Vol. 10, p. 928, para. 6357 ; In re New British Iron Co., Ex parte Be&with, ibid. p. 928, para. 6359; In re Al Biscuit Co., ibid. p. 928, para. 6360.

August 7, 1934 New Zealand Law Journal.

Motor-drivers’ Licenses. Needed Powers of Cancellation and Refusal.

In addressing the Grand Jury at the Wellington Sessions, on July 23, His Honour the Chief Justice, the Rt. Hon. Sir Michael Myers, commented on the fact that there were three trials in which the negligent driving of a motor-vehicle was alleged. His remarks on the need for extension of powers in respect of the cancellation and prohibition of issue of the licenses of certain types of drivers are of considerable interest. His Honour said :-

“ There is one general aspect of the statute law relat- ing to motor-vehicles to which I think that I may refer, though it must not be assumed that my observa- tions are necessarily referable to any of the cases now before the Court. Section 22 of the Motor-vehicles Act, 1924, so far as it is material to the particular aspect of the case that I am referring to, says this :

“ ’ The Court before which any person is convicted of an offence against this Act or of any offence in connection with the driving of a motor-vehicle (other than a first or second offence consisting solely of exceeding any limit of speed) may, if the person convicted holds a motor-driver’s license under this Act, suspend that license for such time as the Court thinks fit, and may also declare the person convicted to be disqualified from obtaining a motor-driver’s license for such further time after the expiration of the license as the Court thinks fit.’ “ I sometimes wonder whether this power goes far

enough. It may well be in criminal charges under this statute where the accused person is acquitted and also in civil actions where negligence in the handling of a motor-car is the gist of the action that the accused person or one of the civil litigants as the case may be either appears temperamentally unfit to drive a motor- vehicle or otherwise appears to be a person not safe in the public interests to be entrusted with a driving license.

“ For example, not long ago in another town I had to try for negligent driving causing death a person who on his own admission had taken during his journey within a period of about three hours immediately preceding the casualty no fewer than nine alcoholic drinks, seven containing beer and two spirits. The jury in that case visited the spot where the casualty happened and found that it was a dangerous locality. They acquitted the accused, and I do not say that they were not per- fectly justified in doing so.

“ The Court in such a case, however, is powerless, and the question is whether the power conferred by subs. 1 of s. 22 of the Act should not be extended. I recognise that such an extension would give the Court a very wide power which would have to be exercised with care and discretion. The safety of the road, howeyer, is a matter of supreme importance, and, there- fore, without expressing any definite opinion I merely make a suggestion, which may or may not be regarded as practicable, but which may be at least worth con- sideration. If the suggestion be thought practicable- that is, the suggestion of the extension of the powers of the section-but the power be considered too drastic to be exercised by a single judicial officer, that difficulty might be overcome by giving a right of appeal.

“ This question of the cancellation of licenses and the prohibition against a person being granted a license for a period of years is a matter which is exercising the

minds of the authorities in other countries as well as New Zealand. I noticed, for instance, in an issue of the English Law Journal of April 28, 1934, this state- ment in one of the editorial notes :

“ We observe that the Home Secretary has stated in the House of Commons that some Benches of Magistrates have, in response to his recent inquiry, expressed the view that the power of suspension should be extended to those cases of careless driving to which it does not apply.”

“ I cannot tell you just precisely what that means,” concluded His Honour, “ but it evidently has reference to some such question as that on which I thought it within my province and my duty to make these few observa- tions to you.”

Recent English Cases. Not@-up Service.

BANKRUPTCY. Bankruptcy-Solicitor’sLien-Priority-Costs-In ~~DEBTOR

[No. 29 of 19311; WILD V. PETITIONING CREDITOR (Ch. D.).

The solicitor for a debtor who has successfully appealed from a receiving order may be given a charging order over costs ordered to be paid to the debtor in priority lo other claims against that amount.

As to a solicitor’s lien and charging order : see HALSBURY, 26, para. 1346 et seq. ; DIGEST 42, p. 290 et seq.

COMPANIES. Companies-Merger-Objection-Locus Standi- UltraVires-

INTERNATIONAL MERCANTILE MARINE Co. (INC.) u. OCEANIC STEAM NAVIGATION Co., LTD. (Ch. D.).

Proceedings to impeach the actions of companies OT their directors on the ground of ultra vires or otherwise cannot be maintained except by shareholders.

As to ultra vires acts of companies : see HALSBURY, 2nd Edn., 5, para. 539 et seq. ; DIGEST 9, p. 465 et seq.

COPYRIGHT. Copyright-Music-News Film-Fair Dealing-HAwKES &

SON v.PARA~~~uNTFILM SERVICE,LTD. (C.A.). The unauthorised reproduction of a ” newe film ” of copy-

right music played during the happening of an event por- trayed is a breach of the copyright of such music.

As to “ fair dealing ” with copyright works : see HALSBURY, 2nd Edn., 7, para. 895 et seq. ; DIGEST 13, p. 206 et seq.

DIVORCE. Divorce - Collusion - Supplemental Petition - SANDZER u.

SANDLER, DAVIES AND JOHNSTONE (C.A.). If a principal petition fails on the ground of collusion, a

supplemental petition alleging adultery with another co- respondent fails also.

As to collusion in divorce : see HALSBURY, 2nd Edn., 10, para. 1CCO et seq. ; DIGEST 27, p. 333 et seq.

Divorce-Res Judicata-Paternity of Child-Maintenance L. vu. L. (P.D. & A.).

Where a decree of divorce has given the custody of “ the child issue of the marriage” to one party, the other party will not afterwards be allowed to dispute the paternity of the child.

As to the effect of orders for custody, etc. : see HALSBURY, 2nd Edn., 10, para. 1181 et seq. ; DIGEST 27, p. 450 et seq.

NEGLIGENCE. Negligence-Runaway Horse-Police Officer-Duty-HaYNES

V. G. HARWOOD AND SON (K.B.D.). The doctrine volenti non fit injuria does not apply to a

police officer who intervenes to stop a runaway horse.

As to volenti non fit injuria : see HALSBURY, 21, pare. 798 et_seq. ; DIGEST 36, p. 135 et seq.

194 New Zealand Law Journal. August 7, 1934

Some Difficulties under the Destitute Persons At C.

By GEOR~:E I. JOSEPH, LL.M.

Probablv no Act is invoked as often as the Destitute Persons A&, and no Act presents greater anomalies and difficulties. The Destitute Persons Act, 1910, seems to have been framed with an eye to expediency rather than to uniformity.

The elasticity with which parties are able to choose their venue often creates hardship and difficulty. No provision is contained in the Act for venue of proceedings. A complainant or informant under the Act can there- fore issue proceedings in any Magistrate’s Court Registry irrespective of the place of residence of either party. Thus a wife resident in Auckland can proceed against a husband in Wellington through the Magistrate’s Court at Christchurch. Similarly an order made in Welling- ton can be varied or enforced in any other Court. NO doubt this has the merit of expediency, but often hard- ship results. The Act gives the Magistrate almost unfettered discretion and the maxim quot homines, tot sententiae is a true one. Take, for example, a case where a wife resident in Wellington obtains a maintenance order against her husband in Auckland. The husband is able to apply for a variation in the Court at Auckland. If the wife wishes to oppose the applica- tion, she must have her evidence taken in Wellington or proceed to Auckland and appear at the Court there- “ Hobson’s choice ” as a rule. The husband thus often obtains a psychological advantage from the absence of the other party.

Another difficulty often confronts a Magistrate where counsel for the husband, who is being proceeded against for a maintenance order, applies for adjourn- ments on legitimate grounds. The Court has no power under the Act to make an interim maintenance order, and often the wife is a destitute person in the truest sense of the term until her application is heard by the Court. An instance was recently given in an Auckland Court where three adjournments had been granted to the husband on account of his absence from the city on business. It was shown at the subsequent hearing that the wife and her three children had subsisted on one meal a day during the interim and although the Magistrate ordered the husband to pay a sum on account of past maintenance, this did not of course eradicate the memories of the past three weeks’ hardship.

Another anomaly arises on account of the conflict between s. 43 of the Destitute Persons Act, 1910, and s. 83 of the Shipping and Seamen Act, 1908. Subsection 2 of s. 43 of the first-named Act with reference to the attachment of salaries and wages for maintenance moneys, reads as follows :-

“ Any such attachment order may be made against any person who is proved to the satisfaction of the Magistrate to be an employer of the defendant against whom the main- tenance order is made.”

However, under the Shipping and Seamen Act, 19C8, all charging orders against the wages of seamen are invalid. The case of Franklyn V. Frankly% 1929 M.C.R., decides that a seaman’s wages cannot be attached for maintenance moneys. The earlier Act evidently overrules the seeming unfettered power of s. 43 of the Destitute Persons Act, 1910. It is difficult to appreciate

-

;he reason for this exception, and it is sometimes almost .mpossible to enforce an order against a seaman owing 50 his absence at sea.

A further anomaly has been created by the passing of ;he Destitute Persons Amendment Act, 1926. The Act gives power to register in the Magistrates’ Court, t maintenance order made in the Supreme Court and ihereon to proceed as though it were an order made by t Magistrate under the authority of the Destitute Persons Act, 1910. The Magistrates’ Court has power mly to deal with the custody and maintenance of :hildren under the age of sixteen years. However, ;he Supreme Court can award custody and maintenance If an infant under the age of twenty-one. It appears, ;herefore, that a maintenance order made in the Supreme 3ourt in favour of an infant over the age of sixteen, :an be enforced only through the machinery of that Court.

Section 2 (4) (a) of the Destitute Persons Amendment Act, 1930, states that any order for the payment of maintenance of an amount over E3 per week and made n the Supreme Court cannot be increased by the Magis- brates’ Court. Tnere seems to be no reason for this, 5s there is now no limit on the amount of a maintenance order in favour of a wife made in the Magistrates’ Court under the authority of the Destitute Persons Act, 1910.

Company Law. Registration of Agreement for Sale and Purchase.

By L. W. GEE, LL.M.

Section 89, 11 (6), of the Companies Act, 1933, pro- vides that

“land held by a company under an agreement for sale and uurchase shall be deemed to be the property of the company subject to a charge created by the ag>eekent and securing the balance of purchase-money for the time being unpaid.”

It would, tierefore, appear that if a company buys land, a copy of the agreement for sale and purchase must be delivered for registration within twenty-one days of the execution of the agreement.

It is unfortunate that no definition of “ agreement for sale and purchase ” is given ; for every contract for the sale of land is an agreement for sale and pur- chase and land is held under the agreement as from the date of the contract.

I f this is the case, practically every contract for the purchase of land by a company will have to be regis- tered ; for even where the whole of the purchase-money is to be paid forthwith it is seldom that settlement takes place within three weeks from the execution of the contract of sale.

The Language of Innocence.-“ I recall the pleading of an eloquent barrister who travelled the Northern Circuit in my day,” said Lord Hanworth, M.R., recently. “ When asking the jury to give credit to his client’s case on account of the attitude the latter had taken when arrested, he said : ‘When charged, did he run away ? No. He stood his ground, and in the language of innocence told the policeman to go to Hell.’ ”

August 7, 1934 New Zealand Law Journal. 195

New Zealand Conveyancing. By S. I. GOODALL, LL.M.

Affiliation Agreement.

An affiliation agreement, or as it is sometimes called a bastardy agreement, is one providing for payment by the putative father towards maintenance of an illegitimate child and usually acknowledging pat.ernity. The mother of the child may be a spinster or a married woman, but there is a presumption in favour of the legitimacy of a child born during marriage, which can be rebutted only by conclusive evidence : Banbury Peerage Case, (1811) 1 Sim. & St. 153, 57 E.R. 62 ; the Poulett Peerage, [1903] A.C. 395 ; and see Mart v. Mart, [1926] P. 24. The mother of an illegitimate child has in general the right to the custody of the child and the right to direct its secular and religious education : R. v. Bumdo, Jones’ Case, [1891] 1 Q.B. 194 CA. In v-e Carrot& [1931] 1 K.B. 317. Although an illegitimate child is at common law f&us nullius with no proper surname but that acquired by repute, nevertheless not only the putative father (so adjudged) and the mother of such a child, but also any “ near relative ” as defined in s. 4 (2) of the Destitute Persons Act, 1910, is liable for the maintenance of the child if he is destitute.

An affiliation agreement commonly provides for pay- ment by the putative father of a lump sum for the expenses incidental to the birth and of periodical pay- ments for the maintenance of the child ; or occasionally for payment of a lump sum for both such purposes. In the latter case it is desirable for practical reasons to join in the agreement a surety for due observance thereof by the mother. The agreement always includes the promise of the mother to maintain and educate the child. This is a sufficient consideration to support the putative father’s promise to pay : Jennings v. Brown, (1842) 9 M. & W. 496, 152 E.R. 210 ; Smith v. Roche, (1859) 6 C.B. N.S. 223, 141 E.R. 440.

No such agreement will affect the liability of the father of an illegitimate child to exposure to affiliation or maintenance proceedings in respect of the child or the liability of the father for maintenance of the child, but regard being had in any such proceedings to the existence of such an agreement, an order may be refused : Tne Destitute Persons Act, 1910, s. 13 ; FoZZzt v. Koetzow, (1860) 2 E. & E. 730,21 E.R. 274.

An instrument effecting an affiliation agreement is liable for stamp duty according to its form, either as an agreement or as a deed not otherwise charged.

If the last words in cl. 1 of the subjoined agreement (immediately preceding subcl. (1) ) are omitted the liability of the father to pay maintenance under the agreement will cease upon the mother’s death : James v. Morgan, [1909] 1 K.B. 564.

As to the statutory liability of the estate of a deceased parent for future maintenance of an illegitimate child unrler the age of sixteen years, see s. 16 of the Destitute Persons Act, 1910.

The subjoined precedent is designed for the ordinary case where paternity is admitted. If paternity is denied, but the putative father nevertheless enters into the agree- ment the nomenclature of “ father ” is inappropriate, an1 it is better to omit the interpretation clause and in

lieu refer to the putative father throughout as “ t,he said M.N. (proper name).” The second recital will in consequence require amendment to recite an allegation of paternity by the mother and the denial thereof by the putative father, and the agreement of the putative father nevertheless to pay maintenance.

Agreement acknowledging Paternity of Illegitimate Child and agreeing to pay Maintenance therefor.

AGREEMENT made this day of 19 BETWEEN M.N. of etc. (hereinafter called “ the father “) of the one part AND X.Y. of etc. (hereinafter called “ the mother “) of the other part.

WHEREAS at on the day of 19 the mother gave birth to an illegitimate child since duly registered under the name of V.Y. (herein- after called “ the child “).

AND WHEREAS the father is the father of the child as the parties hereto do hereby severally admit and declare.

AND WHEREAS the parties hereto are desirous of declar- ing hereby their respective rights and liabilities con- cerning the child its maintenance and education.

Now IT IS HEREBY AGREED AND DECLARED by and between the parties hereto as follows :-

1. IN consideration of the premises and of the pro- visions hereinafter expressed and on the part of the mobher to be observed and performed the father shall an 1 will during his life and his personal representatives will after his death duly and punctually pay to the mother or to such person or persons as she shall in writing from time to time direct during the life of the mother and to her executors or administrators after her death :

(a) The sum of g on the day of 19 for the expenses of and incidental to the birth of the child.

(b) The further sum of ;E on the day of every week henceforth for or towards the maintenance support education and benefit of the child until the child shall attain the age of [sixteen] years or previously die the first of such weekly payments to be made on day the

day of 19 .

2. THE father shall not nor will annoy molest or disturb the mother or the child nor in any way interfere with the mother in her mode of living or maintaining and educating the child.

3. THE father will pay the costs of and incidental to the preparation execution and stamping of this agreement.

4. IN consideration of the premises and of the pro- visions hereinbefore expressed and on the part of the father to be observed and performed the mother shall and will henceforth until the child shall attain the age of [sixteen] years or previously die at all t,in-es keep the child in her own or other proper custody and pro- vide the child with good proper suitfable and sufficient food clothing shelter medical and dental attention and educat.ion.

5. THE mother shall not nor will at any time during the continuance of this agreement suffer the mainten- ance of the child to become a charge upon any public or charitable institution.

196 New Zealand Law Journal. August 7, 1934

6. THE mother shall and will at all times henceforth indemnify the father and his estate against all claims demands and expenses actions proceedings and costs whatsoever in respect of the maintenance custody or education of the child.

7. THE mother shall not nor will at any time here- after annoy molest or disturb the father nor so long as the father shall continue to pay the sums hereinbefore provide1 institute or prosecute nor suffer to be instituted or prosecuted any proceedings whatsoever for an affilia- tion or other order adjudging the father to be the father of the child or for a maintenance or other order for payment by the father of any sum or sums of money towards the maintenance or education of tl,e child.

8. THE mother shall not nor will so long as the father shall continue to pay the sums hereinbefore provided at any time or in any manner publish or assert to any person or persons whomsoever that the child is or may be the child of the father nor in any case permit the child to bear or be called by the Christian name or the surname of the father.

9. ‘IF the father shall die during the continuance of this agreement no liability for payment thenceforth of any sum or sums for the future maintenance of the child shall attach to the executors or administrators or the estate of the father other than the liability to pay the said weekly payment of the sum of % each until the child shall attain the age of [sixteen] years,

As WITNESS etc.

SIUNED etc.

SIGNED etc.

A Centenary Memorial to “ Elia.“-The proposal of the Elian Society to erect a memorial to Charles Lamb as near as possible to the old site of Christ’s Hospital, where he was educated, will, we feel sure, commend itself particularly to those whose professional avocations take them from time to time to what Lamb himself called “ the most elegant spot in the metropolis “- the Temple. The occasion for the proposal is an ap- propriate one, for the end of this year sees the centenary of Lamb’s death. There is, of course, a commemorative fountain in the Temple Gardens ; but it is not accessible to the public, and the almost unique position which he holds in the minds of men-the increasing recognition, not merely of his literary genius, but of the self-sacrificing unselfishness of his life-make it, in the opinion of the Law Journal (London), unnecessary, in order to ensure the success of the proposed memorial fund, to do more than call attention to it. The Essays of Elia have given, and will continue to give, pleasure to millions ; whilst Lamb’s devotion of his life to the care of his unfortunate sister affords an example of altruism not often seen. This is strikingly brought home to the reader of Miss Joan Temple’s play Charles and Mary, which was so well played in Auckland last month under the capable direction of Miss Ysolinde McVeagh, daughter of our Mr. Robert McVeagh, the highly esteemed Auckland barrister. The Elian Society’s proposal, which is spon- sored by Sir James Barrie, Mr. E. V. Lucas, and Mr. Edmund Blunden, is for the erection of a suitable memo- rial, with a bronze portrait bust of Lamb, in the Garden of Christ Church, off Newgate Street.

Bench and Bar. Mr. C. V. Lester, recently reported here as having been

admitted as a solicitor, was in fact admitted as a barrister and solicitor.

Messrs. A. H. Johnstone, K.C., and F. L.-G. West, of Auckland, left on July 24 on a holiday to the Far East, and expect to be away about three months. They propose visiting Honolulu, China, Japan, the Philippines, and the Dutch East Indies.

Mr. G. I. Joseph, LL.M., of the staff of Messrs. Tread- well and Sons, Wellington, left for England to continue his studies at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, for the degree of Ph. D. He proposes to apply for a call to the English Bar by one of the Inns of Court.

Correspondence. [It is to be understood that the views expressed by

correspondents are not necessarily shared by the Editor.]

Insurance Companies and Leave to Swear to Death.

The Editor, NEW ZEALAND LAW JOURNAL,

Wellington. Sir,

In the last number of the JOURNAL there appeared Practice Precedents for an application for leave to swear to death. This calls to mind an interesting point : Probate or letters of administration are prima facie evidence of death : Administration Act, 1908, s. 14. An insurance company must be satisfied with reasonable proof of death: Braunstein v. Accidental Death Co., 5 L.T. 550, and is therefore bound to pay to an executor or administrator whose grant depends upon death sworn pursuant to leave of Court. Now, if the supposed deceas- ed reappears alive, the grant is void ab initio : Fraser v. Fraser, (1909) 28 N.Z.L.R. 962 ; Ex parte Keegan, (1907) 7 N.S.W.S.R. 565, In the Goods of Napier, 1 Phillim. 83, 161 E.R. 921 ; and the insurance company would be bound, subject to the usual rules, to reinstate the policy. The company would be left with its right of action against the ex-administrator, and such right would in many cases be worthless. The company usually therefore, asks the administrator for a bond with sureties to provide against the reappearance of the “de- ceased ” ; but it seems that the administrator need not give such a bond unless he chooses to.

By s. 19 of the Public Trust Office Act, 19C8, the Public Trustee is protected in such a case, and his acts as administrator are declared to be as good, valid, and effectual as if he had lawfully been the administrator.

I am wondering whether .any practitioner has had occasion to consider this point, and whether any attempt has ever been made on behalf of an insurance company to ask the Court, on the hearing of the application for leave to swear to death, to grant leave subject to the Public Trustee being appointed administrator. This would protect the insurance company.

July 26, 1934. Yours, etc. G. R. POWLES.

August 7, 1934 New Zealand Law Journal. 197

Australian Notes. By WILFRED BLACKET, K.C.

A Soulless Heel.-Mrs. M. E. Wills of Sydney purchased from David Jones, Ltd., a pair of shoes. She said she wanted “ shoes for walking ” and was shown- either forthwith or ultimately-a pair which she approved of and paid for, but on the third occasion of her walking out in them the heel of one shoe came off and she fell heavily, breaking a leg. She then sued David Jones for breach of an implied warranty that the shoes were safe for use in walking. Upon trial, Coram Curlewis, J., and a jury in the District Court, a verdict for g.13 19s. 8d. was returned, the amount including 28 19s. 8d. for out-of-pocket expenses and ;E5 for the broken leg. As soon as he had recorded the verclict, Curlewis, J., said that it was “ absolutely idiotic ” and at once granted a new trial limited to the issue of damages. Defendant appealed on all points, and the Supreme Court held that there was a warranty and breach and that Curlewis, J., was right in ordering a new trial on the issue of damages, but that he ought not to have told the jury that their verdict was “ absolutely idiotic.” Curlewis, J., in his own Court, took occasion to mention that he had not exercised his descriptive powersregarding the verdict until the jurors had departed thence and were out of hearing, and that their Honours of the Supreme Court must have thought that the verdict was sub- stantially of the nature and quality stated by him or else they would not have upheld his order granting a new trial. Now the High Court has granted special leave to appeal, and upon the hearing the unreported case of Australian Knitting Mills v. Grant will no doubt be vehemently debated. A brief note of the facts and decision in this case appears in my Notes, 9 N.Z. Law Journal, 21, p. 301, and as I ventured to mention my

view as to the quality of the law laid down by the majority decision and as to the mischief likely to be wrought thereby, I need not now add that I shall watch the pre- sent appeal with much interest.

A New Zealand Visitor.-At Aspendale, Victoria, Frederick Cusdin, seeing Miss Erene Panioty walking alone on a lonely road on a dark night, hit her on the head with a bottle causing grievous bodily harm, and when convicted of the offence, and sentenced to eighteen months’ imprisonment and ten lashes he collapsed and was carried, unconscious, from the Court. He should have been made of sterner stuff, for ten lashes would not be more unpleasant than to be hit on the head with a bottle by a perfect stranger while walking on a lonely road on a dark night at Aspendale, Vie., but the terror that he showed on hearing the sentence shows how effective the lash would be as a deterrent to men of his class. The only plea urged in mitigation on his behalf was that he was not an Australian but had come from New Zealand, and that he had had a fall when riding in the Great Northern Steeplechase.

“ God Bless Our Home.“-William Robert Sproule of Sydney petitioned the Divorce Court for a decree for restitution of conjugal rights. He and his wife, Belinda Maud Sproule, had agreed to separate in July, 1933, under an agreement that provided that she should not proceel against him for alimony, maintenance, or support ; and Belinda Maude ha.d then written him saying, “ I insist upon your leaving my home at once an,1 never return. . . . I’ll never trouble you for anything so long as you get out and stop out.” It did

Although it is perhaps beyond my range, I should like to have another stab at the New South Wales State Lottery, especially because I know that Government approval of crime is a thing abhorred in the Dominion. The year before the State lottery started on its loath- some career the voluntary subscriptions to public hos- 1 pitals totalled &317,000 ; in the previous year, 1919, before the proposal to establish a lottery had been made the total had been &564,000 ; in 1931, the year when the lottery started the total fell to &193,000 and in 1933 it was aEl93,OOO. And now lottery receipts are dimin- ishing rapidly, for in March, April, and May, 1934, only 1,600,OOO tickets were sold as against 2,100,OOO in those months of the previous year. The way of the political transgressor seems to be rocky.

I :

not appear that the dove of peace had ever returned to bless William and Belinda ; but the Judge, probably influenced by the thought that “ man wants but little here below,” was able to find that the petitioner was sincere in his desire for the return of the respondent, and to order accordingly.

Cover Notes.-There is much competition between the companies insuring workmen in New South Wales and consequently they are ever ready to oblige. It is necessary to mention this in order to give verisimilitude to the statement of following facts. Alan Schwartz, furniture maker, in December, 1932, engaged Clement Devlin as assistant, and on the 13th of that month by telephone informed the Queensland Insurance Company of the employment and a cover note was sent him by that day’s post. On the 14th idem, Devlin accidentally injured the middle finger of his left hand, and the com- pany being informed, a “ notice of injury ” form was sent to Schwartz and completed and returned by him on the 15th. Sometime in February, 1933, the company agreed to allow payment of the premium to stand over “ for a while,” and on March 25 Schwartz, having received a summons from Devlin, handed it with SE3 1s. for the premium to the company’s officer. The company re- fused to accept the money or to defend the case. Devlin obtained an award for g102 15s. and, as he could not collect anything from Schwartz, he claimed payment of the amount frolm the Queensland Insurance Company. The claim was resisted on the ground that Schwartz had not insured his liability with the company. Judge Perdriau held that the cover note which incorporated by reference the terms of the policy to be issued operated as an insurance during its currency. He held, further, that the company was bound under the circum- stances to accept the premium when tendered and to issue a policy in accordance with the Workers’ Com- pensation Act (N.S.W.), 1926-9.

Brief Mention.-In Melbourne, Herbert Scott and Patrick Sabelburg were charged with having carried firearms-to wit, pea-rifles-on one of the ” slippery pat!ls of youth”-to wit, Heidelberg Road-on a Sunday. They pleaded that as trainees they were “ soldiers of the King ” and not liable to any of the laws relating to firearms. They were only fined g2 each, the Court having no power to award any penalty for impudence.

In the Probate Court, Sydney, Cor. Harvey, C. J. E., Larkspurr of the Junior Bar was moving to pass the twenty-fifth. accounts in an estate and for commission. The soft pedal is always down when he speaks in Court, and on this occasion his voice was almost as “ soft as a prayer.” Harvey listened without comment while one affidavit was being read, but as counsel began on the next one he said, “ You need not be quite so rever- ential, Mr. Larkspurr, your testator has been dead for twenty-six years.”

198 New Zealand Law Journal. August 7, 1934

New Zealand Law Society. Council Meeting.

(Concluded from page 184.)

Intoxicated persons.- (a) Right when arrested to have examination by own

doctor without police being present. (b) Whether solicitor should be prevented from inter-

viewing client until latter considered aober by police. The following letter was received from the Auckland

District Law Society :- “ It appears from a complaint recently made to this Society

that when a person arrested on a charge of intoxication is being medically examined by a doctor consulted by the person arrested or his solicitor a constable must be present. It would seem further that it is the practice of the police, where they consider the person in custody too intoxicated to transact business, to refuse to permit his solicitor to interview him. That the foregoing is the case appears to be confirmed by a letter from the Commissioner of Police bearing date the 16th April, which letter is on the Society’s file forwarded herewith. In the opinion of my Council these matters should be placed before your Council for consideration, and I accord- ingly forward the file on which will be found letters setting out the position more fully, and also the opinion of members of my Council.”

The opinion expressed for the Council of the Auckland District Law Society was as follows :-

“ In my opinion an accused person who is going to be charged with an offence of this nature should be entitled to have an examination by his own medical appointee, with- out the police being present. Obviously questions may arise which may require discussion between counsel and medical adviser, and the prisoner, and the accused is going to be seriously hampered if the interview has to take place in the presence of the police.

“ I do not agree with the Commissioner of Police that the Department should be at liberty to determine when solicitors may see their clients, or that the Department should be per- mitted to prevent an interview upon the ground that the client is not sufficiently sober to transact business. Par- ticularly in such a case as this, where the very offence with which the prisoner will be charged is one involving intoxica- tion, it seems to me that immediate facilities should be granted to the accused’s counsel to interview him and to obtain such medical evidence as he considers necessary, I see no force in the Commissioner’s statement that it is obviously a safe and proper procedure to give the accused time to become sober before allowing him to transact business for which he must be held responsible. This surely is a matter between the accused and his counsel, and in my opinion should not be allowed to interfere with the freedom which should be accorded in the interests of the prisoner, to his counsel.

“ As the principle set forth in the Commissioner’s letter would no doubt be applied throughout New Zealand, it may be desirable to refer the matter to the New Zealand Council with a view to obtaining some uniformity throughout the Dominion.”

It was decided that the above opinion be approved and that a committee consisting of Messrs. A. T. Donnelly, H. F. O’Leary, and C. A. L. Treadwell should wait on the Commissioner of Police and place before him the views of the Society.

Limited Land Transfer Titles-Requisitions.-The Auckland District Law Society raised the following questions :-

“ (a) Who should make the declaration required to remove Requisitions Nos. 2 and 3 of the Regis- trar’s minutes issued under the Land Transfer (Compulsory Registration of Titles) Act, 1924, and

“ (b) At whose cost should this be done ?”

A committee, consisting of Messrs. F. B. Adams, H. S. Adams, and C. L. Calvert, was appointed to enquire into the matter and report to the next meeting.

Leasehold Titles-Cost of Certificate of Title.-The Wanganui District Law Society wrote as follows :-

“ A ruling is desired on the following points in connection with Leasehold Titles. Section 3, subsection (1) of the Land Transfer Amendment Act, 1925, provides as follows :-

“ ‘ In the case of any lease, including a lease forming a folium of the Register-book in the office of the Registrar, the Registrar may, if in his opinion the number or nature of the entries thereon or in the Register-book renders it expedient so to do, issue to the registered proprietor a certificate of title for his leasehold interest.’

“S. was the holder of five leases, particulars of which are set out hereunder :

“ 1. Lease originally granted to T.T. transferred by him to A.S.R. and by him to S., the lease and transfer having been registered prior to the transaction now in question and no leasehold title having previously been issued.

“ 2. Lease to A.L.B. transferred to S. but neither lease nor transfer having been registered prior to the present transaction.

“ 3. Lease originally to A.L.B. registered prior to present transaction, but transfer to S. not having been registered prior to present transaction.

“ 4. Lease to S. registered prior to present transaction and no leasehold certificate having been issued prior to present transaction.

“ 5. Lease to S. in same position as 4.

“ S., the holder of all the leases, agreed to sell same to M. who gave a mortgage back to S., and also a second mortgage to an outsider. The following sets out the events in the case of each lease on registration of the transfer and subse- quent documents.

“ Lease No. 1. This already had two transfers registered on it, the last being the transfer to S., the present vendor. The District Land Registrar issued a leasehold title in the name of S. and entered the transfer to M. and subsequent mortgages on this.

“In the case of lease No. 2 not previously registered, the District Land Registrar issued a leasehold title in the name of the original lessee, and registered on this the transfer to S., the transfer to M. and subsequent documents.

“ In the case of lease No. 3, this had been previously regis- tered but the transfer to S. had not been registered. The District Land Registrar issued a title in the name of the original lessee and registered on this the transfer to S., the transfer to M. and subsequent documents.

“In the case of lease No. 4, this had been registered but no title issued. The District Land Registrar issued a title in the name of S., and registered thereon the transfer to M. and subsequent documents.

“ In the case of lease No. 5, this was dealt with as mentioned in 4 above.

“ The question is, who should pay the cost of the leasehold titles ? It is apparently becoming the practice to issue leasehold titles in every case, and the point will apparently arise in every case in future where an existing lease for which no title has been issued is being transferred.

“ It will be observed that it is not obligatory on the District Land Registrar to issue the title, and it must be taken that in doing so he exercises the discretion given to him by the Act. The necessity for the issue of the title only arises on presentation of the documents for registration and it may be said that, until the time when the District Land Registrar exercises his discretion, the vendor has done all that is re- quired of him by handing his purchaser a registered lease and a registrable transfer. The discretion of the Registrar must be exercised after the documents have been presented and accepted for registration, and this would appear to make the case different from that of a limited title where there is no discretion, and the registered proprietor is bound to obtain a limited title before registering any further dealing.”

It was decided to refer this question also to Messrs. F. B. Adams, H. S. Adams, and C. L. Calvert for a report.

August 7, 1934 New Zealand Law Journal.

Practice Precedents. In Divorce : Leave to Set Down.

Where the pleadings are concluded any party to the cause may set down for trial at any sitting of the Court at the place at which the same is to be tried by entering the cause in a list to be kept for that purpose by the Registrar. Such entry must be made at least six clear days before the day appointed for such sitting ; and, except by leave of the Court, which may be given ex parte in an undefended case, no cause may be tried at such sitting which has not been so entered : R. 51 of the Divorce Rules : Sim on Divorce, 4th Ed. 69, and see the notes to the rule.

It is to be observed that this rule is to be strictly complied with but in Nicholson v. Nicholson, [1926] N.Z.L.R. 111, a Restitution suit, leave was given where the time had not expired and the respondent consented, although no appearance had been entered or answer filed.

In 1926 it was directed by the Hon. Mr. Justice Reed that in all cases where leave to set down was sought an affidavit in support of the motion must be filed setting out the steps that had taken place from the time of the filing of the petition to the date of the filing of the motion.

By a direction of the Right Hon. the Chief Justice at Wellington in 1934, a full, separate, and independent affidavit of search must be filed in all suits for Divorce where no appearance has been entered ; and when leave to set down is sought the affidavit of search must be filed apart from any information as to appearance or search that may be contained in the affidavit required to be filed in support of the motion for leave to set down.

In this precedent it is assumed the suit is undefended, in which case the motion is ex parte and does not there- fore require to be served. (Otherwise it would be a notice of motion and required to be served. The notice of motion must then allow three clear days from service for hearing and must contain the usual intimation at

the foot that it is issued by whose address for service is at etc.)

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF NEW ZEALAND.

. . . ..._......,._ District.

..,. _._. ,.,. _.__ Registry.

BETWEEX A.B. etc. petitioner and C.D. etc. respondent.

Mr. of counsel for the above-named petitioner TO MOVE before the Right Honourable Sir Chief Justice of New Zealand at his Chambers Supreme Court-house at on day the day of 19 at the hour of 10 o’clock in the forenoon or so soon thereafter as counsel can be heard FOR AN ORDER that leave be granted to the petitioner to set this suit down for hearing at the sittings of this Court which commenced at on Monday the day of 19 UPON THE GROUNDS that no appear- anoe has been entered or answer filed by the respondent in the said suit and that the time allowed to the respondent for filing an answer expired on the day of 19 that is to say between the last day for setting down cases for trial (being the day of 19 ) and the day of the opening of the ensuing sessions (being the day of 19 ) AND UPON THE FURTHER GROUNDS set out n the affidavits of filed in support hereof.

-

Dated at Wellington this day of 19 .

Solicitor for petitioner.

Certified correct pursuant to rules of Court to be correct.

Counsel moving.

Reference: His Honour is respectfully referred to R. 51 of the Divorce Rules and to the case of l3staZZ v. Estall, (1911) 30 N.Z.L.R. 466.

Counsel moving.

-

AFFIDAVIT IN SUPPORT.

(Same heading.)

I of the City of solicitor make oath and say as follows :-

1. That I am a solicitor in the employ of solicitor for the petitioner in this cause and am personally acquainted with the matters hereinafter referred to.

4. That the petition herein for restitution of conjugal rights was filed and the citation herein sealed on the day of

19 .

3. That the said citation was duly served on the respondent herein together with a certified copy under seal of this Court of the said petition at on the said day of 19 .

4. That the time within which an answer was required to be filed by the respondent expired on the day of 19 .

5. That the last day for setting down cases for trial was the day of 19 .

6. That the ensuing sessions of this Honourable Court for the trial of divorce suits commenced on the day of 19 .

7. That no appearance has been entered or answer filed by or on behalf of the respondent.

Sworn etc.

AFFIDAVIT OF SEARCH. (Same heading.)

I of the City of solicitor make oath and say as follows :-

1. That I am a solicitor in the employ of the solicitor for the petitioner in this suit.

2. That I did on the day of 19 search in the divorce proceedings’ book kept in the registry of this Court at to ascertain whether or not any appearance had been entered by or on behalf of the respondent m this suit and I found that no appearance had been entered by or on behalf of the said respondent.

3. That the time limited by the citation sealed herein for filing an answer by the respondent to the petition filed herein expired on the day of 19 .

Sworn etc.

AFFIDAVIT OF SERVICE.

(San&e heading.)

I of the City of solicitor make oath and say as follows :-

1. That I am a solicitor in the employ of for the petitioner in this suit.

solicitor

2. That the citation hearing date the day of 19 issued under seal of this Court against the respondent in this suit and now hereunto annexed marked with the letter ” A ” was duly served by me on the said C.D. the said respondent at by leaving with her a true copy thereof on the day of 19 .

3. At the same time and place I delivered to the said C.D. personally a certified copy under seal of this Court of the petition filed in this suit and also a true copy of the affidavit of the petitioner filed in support of the said petitioner.

4. That the said C.D. is personally known to me by reason of the fact that 1 have known her to speak to for a number of

years having acted professionally for her some years ago.

Sworn etc.

New Zealand Law Journal. August 7, 1934

ORDER FOR LEAVE TO SET DOWN. day the day of 19 *

Before the Honourable Mr. Justice UPON READING the motion filed herein and the affidavits of service and of search and the affidavit filed in support of the said motion AND UPON HEARING Mr. of counsel for the petitioner IT IS ORDERED that leave be and the same is hereby granted to the petitioner to set down this suit for hearing at the sittings of this Honourable Court which com- menced at On the day of 19 .

By the Court. Registrar.

Bills Before Parliament. Finance. (RT. HON. MR. COATES.) Part II. Provisions relating

to National Expenditure Adjustment Act, 1932. Cl. 13.- This Part to be read with National Expenditure Adjustment Act. Cl. 14.-Extension of period during which Part III of principal Act (effecting reductions of interest and rent) to continue in operation until April 1, 1937. Cl. 15.-Con- ferring on Governor-General in Council permanent authority to fix rates of interest on deposits with savings-banks. Cl. 16.- Extending authority of Governor-General in Council to fix rates of interest on deposits with building or investment societies. Cl. 17.-Extension of period during which Part VI of principal Act (relating to rates of interest on deposits with trading-companies) to continue in operation until April 1, 1937. Part III. Miscellaneous. Cl. 18.-Repeal of s. 25 of the Finance Act, 1932 (No. 2). Cl. lg.-Extension of powers conferred by s. 60 (2) of Finance Act, 1932, with respect to timber-cutting licenses granted over Native land. Cl. 20.- Restrictions imposed on the application by local authorities (within the meaning of the Local Government Loans Board Act, 1926) of capital moneys derived from sale of assets repre- senting loan-moneys or of other capital moneys representing loan-moneys. Repeal of s. 234 (4) and 289 (5) of the Municipal Corporations Act, 1933.

Mortgagors and Tenants Relief Amendment. (MR. VEITCH.) Cl. 2.-Suspension of personal covenant under mortgages of property owned by religious, charitable, or educational bodies.

Mutual Fire Insurance Amendment. (HON. MR. YOUNG.) Cl. 2.-Trustees (including executors and administrators) may enter into contracts of insurance with associations formed under principal Act.

War Regulations Repeal. (RT. HON. MR. FORBES.) Cl. 2.-War Regulations Continuance Act, 1920, repealed, and War Regula- tions revoked. Saving powers of Public Trustee as Custodian of Enemy Property. Cl. 3.-Consequential repeals of War Regulations Act, 1914; War Regulations Amendment Act, 1915 ; War Regulations Amendment Act, 1915 (No. 2) ; War Regulations Amendment Act, 1916 ; War Legislation Act, 1917 : s. 26 ; War Legislation and Statute Law Amend- ment Act, 1918 : s. 26 ; Reprint of Statutos, Vol. 8, pp. 1038, et seq.

Passports. (HON. MR. YOUNG.) Cl. 2.-Governor-General in Council may make regulations requiring the production of passports by persons arriving in New Zealand from overseas. The Passport Regulations, 1929, made under the authority of the War Regulations Continuance Act, 1920, by Order in Council dated April 24, 1929, unless sooner revoked, to continue in force until regulations made under the authority of this Act come into force, and shall then be deemed to be revoked.

Police Offences Amendment. (HON. MR. COBBE.) Cl. 3.- Governor-General may declare essential industries. Cl. 4.-Offences in relation to essential industries. Cl. 5.- Offences in relation to documents inciting to violence or expressing seditious intention. Cl. B.-Penalty for offences.

Earthquake Protection. (MR. BARNARD.) Cl. 2.-Interpreta- tion. Cl. 3.-Imposition of insurance tax in respect of fire insurances of buildings and contents of buildings. Cl. 4.- Persons liable to insurance tax. Cl. 5.-Assessment of insur- ance tax. Cl. 6.-Quarterly returns of insurances to be made by insurance companies for purposes of this Act. Cl. 7.- Dates of payment of insurance tax. Cl. 8.-Power&o: EIt: missioner of Taxos in respect of insurance tax. . . surance tax payable by persons insuring buildings or contents with insurance companies not carrying on business in New

Zealand. Cl. lO.-Proceeds of insurance tax to be credited to Reserve Fund Account. Cl. Il.-Right of owner who pays insurance tax to participate in distribution of insurance- tax moneys. Cl. 12.-Regulations.

Workers’ Compensation Amendment. (MR. PARRY.) Cl. 2.- Average weekly earnings, how calculated. S. 6 of the Workers Compensation Act, 1922, repealed.