ObESiTY in AmEriCA - Health Advocate

Transcript of ObESiTY in AmEriCA - Health Advocate

H E A LT H A D V O C AT E

H e l p i n g A m e r i c A n s n A v i g At e t H e

H e A lt H c A r e A n d i n s u r A n c e s y s t e m s

A Complete Spectrum of Programs

to Support your Company and Employees

� core Health Advocacy service

� Wellness Advocate

� enrollment Advocate

� independent Appeals Administration

� FmlA support

c O n tA c t u s

For additional information:1-866-385-8033 (toll-free)[email protected]

www.HealthAdvocate.com

q YES! please send me more information about how my organization can save time and money and help our employees better navigate the healthcare and insurance systems.

__________________________________________________________________ nAme title

__________________________________________________________________cOmpAny

__________________________________________________________________street

__________________________________________________________________city stAte Zip

__________________________________________________________________pHOne

__________________________________________________________________emAil

©2008 Health Advocate, inc. W-B-Wp1008

1-866-385-8033 (toll-free)[email protected]

ObESiTY in AmEriCAWOrkplAce sOlutiOns

A B O u t t H i s g u i d e

this publication offers comprehensive research about how the growing obesity epidemic is affecting the workplace and contributing to higher healthcare costs. the research also reviews successful workplace strategies that promote weight loss and address the underlying factors of obesity such as diet, exercise, environment and stress. Following these strategies can help to lower obesity-related risk factors, injuries, absenteeism and, ultimately, to lower healthcare costs.

Health Advocate, inc., the nation’s leading healthcare advocacy and assistance company, provides a spectrum of time- and money-saving solutions to millions of Americans through its extensive employer and other plan sponsor relationships. Our core advocacy program is centered around a team of personal Health Advocates (pHAs), typically registered nurses supported by medical directors and benefits specialists. pHAs help members navigate the healthcare system and resolve clinical, insurance and administrative issues. Our complementary solutions, offered for an additional charge to employers and plan sponsors, include Wellness Advocate, a comprehensive program that features a personal wellness coach supported by online wellness tools; enrollment Advocate; FmlA support and independent Appeals Administration. Health proponent is the consumer version of Health Advocate and is sold directly to individuals and their families.

Founded in 2001, the company is headquartered in suburban philadelphia with sales offices in major cities. Health Advocate has been recognized as one of America’s fastest growing private companies by Inc. 500. Philadelphia Magazine has rated Health Advocate as one of the top 20 Best places to Work.

Health Advocate is not affiliated with any insurance or third party provider. Health Advocate does not replace health insurance coverage, provide medical care or recommend treatment.

For more information, call Health Advocate at: 1-866-385-8033 (toll-free) or via email at [email protected].

HE

ALTH

AD

VO

CA

TE

3043 WA

LTON

RD

SU

ITE 150

PLY

MO

UTH

ME

ETIN

G P

A 19462-9705

NO

PO

STA

GE

NE

CE

SS

AR

YIF M

AILE

DIN

THE

UN

ITED

STA

TES

BU

SIN

ES

S R

EP

LY M

AIL

FIRS

T-CLA

SS

MA

ILP

LYMO

UTH

ME

ETIN

G P

AP

ER

MIT N

O.385

PO

STA

GE

WILL B

E P

AID

BY A

DD

RE

SS

EE

Artw

ork for User D

efined (4.25" x 6")Layout: C

:\Docum

ents and Settings\K

B80K

2\my docum

ents\AR

T WO

RK

\CO

PY O

F TEM

PLA

TES

\julie lyt\HE

ALTH

AD

VO

CA

TE.LYT

August 21, 2006 06:20:32

Produced by D

AZzle D

esigner 2002, Version 4.3.08

(c) Envelope M

anager Softw

are, ww

w.E

nvelopeManager.com

, (800) 576-3279U

.S. P

ostal Service, S

erial #NO

IMP

OR

TAN

T: DO

NO

T EN

LAR

GE

, RE

DU

CE O

R M

OV

E the FIM

and PO

STN

ET barcodes. They are only valid as printed!

Special care m

ust be taken to ensure FIM and P

OS

TNE

T barcode are actual size AN

D placed properly on the m

ail piece to m

eet both US

PS

regulations and automation com

patibility standards.

For additional information:1-866-385-8033 (toll-free)[email protected]

www.HealthAdvocate.com

tOBESITY IN AMERICA

WORKPLACE STRATEGIES AND SOLUTIONS

The rising rate of obesity—called the world’s number one health threat by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)—

has set off a pitched alarm by public health experts. And a growing legion of employers are hearing it loud and clear.1

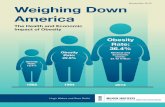

The statistics tell a startling story. About two-thirds of adults in the United States are overweight, according to landmark data from the 2003-2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Worse, more than one-third—or 72 million people—are now deemed obese. Just 4-10 years ago, less than one-quarter of adults were considered obese.2, 3

And the rate does not appear to be slowing. During 2007, adult obesity rates increased in 37 states as reported by the Trust for America’s Health, a Washington-based nonprofit that addresses the prevention of epidemics.4

It’s a threat with a steep price tag. Obesity plays a role in the development of dozens of diseases including diabetes, heart disease, cancer and other serious, chronic conditions which account for 75 percent of healthcare spending.5 In 2000, obesity had cost the U.S. an estimated $117 billion.6 However, the doubling rate of obesity over the past 20 years accounts for almost 30 percent of the rise in healthcare spending.7 Since the late 1990s, businesses spend more than $13 billion in medical costs and lost productivity because of obesity each year.8

Turning these figures around will take dedicated intervention from all sectors—individuals, community, local, state and national government as well as employers. The good news is that when employers take part in the solution—initiating even small changes to fight obesity—the efforts can help create healthier, more productive employees, which can result in lowered healthcare costs.

Obesity costs business $13 billion each year.

Obese workers are sicker, miss more days of work, are more prone to injury and accidents, and incur higher medical costs than employees of average weight.9

Medical expenditures for obese people under age 65 are 36 percent higher than for normal weight people, as shown by one 2002 study conducted by the Rand Corporation. Eric Finkelstein, Ph.D., a health economist at RTI International in Research Triangle Park, North Carolina who has collaborated with the CDC on the health costs of obesity, reports that an average firm with 1,000 employees faces $285,000 per year in extra costs associated with obesity.10, 11

According to a 2004 report by UnumProvident, the nation’s largest provider of disability income protection insurance, short-term disability claims attributed to obesity have shown a tenfold increase in the decade from 1994-2004. The most obese workers had the highest medical claims.12

Added weight can put added strain on the back, knees and hands. Obese workers are more likely to be injured from falls, lifting and strains. Compared to normal weight workers, they are more than twice as likely to file worker's compensation claims. Obese employees also have seven times higher medical costs from those claims and lost close to 13 times more days of work from work injury or work illness than did non obese workers, according to a Duke

* Totals do not add up because of rounding and overlap.

† Includes coronary heart disease, congestive heart failure, part of hypertensive disease, cardiac dyssrhythmias, rheumatic heart disease, cardiomyopathy, pulmonary heart disease, and other or ill-defined "heart" diseases.

Source: American Heart Association. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2008 Update.

ESTIMATEd dIRECT ANd INdIRECT COSTS Of MAjOR CARdIOvASCulAR dISEASES ANd STROkE*

United States, 2008

0 50 100 150 200 250 300

$287.3

$156.4

$65.5

$69.4

Heart diseases†

Coronary Heart disease

Stroke

Hypertensive disease

Heart failure $34.8

The Burden to Businesses

Disability

Worker's Compensation

2 Health Advocate, Inc.

In Billions

University Medical Center analysis. Workers who were the most obese had the highest rate of claims and lost workdays.13

Other costs to employers cannot always be clearly quantified. Researchers from Stanford University School of Medicine noted that one of the unintended consequences of the obesity epidemic in the U.S. is that medical cost increases also increase premiums to the point that other employees may opt out of their insurance plan. And some employers may drop coverage altogether for their employees. This could leave uninsured employees less likely to see their doctors or use preventive care, leaving them more at risk for disease or vulnerable to the worsening of an existing disease.14

Many employers face the expense of investing in office equipment to accommodate their obese employees. For instance, standard chairs may not be suitable for employees who weigh over 300 pounds. Obese employees may also require a split keyboard or other special equipment.15

Obesity is a disease in which excess body fat has accumulated to such an extent that health may be negatively affected. One tool that doctors use to classify weight is the body mass index (BMI). The BMI is the ratio of weight to the square of height (measured in kilos and meters). A person is categorized as “obese” when the BMI hits 30 and over or is 30-40 pounds overweight.16

Additional Consequences

Workplace Accomodations

3Health Advocate, Inc.

The Basics of Obesity

Source: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “Prevention Makes Common ‘Cents’,” Washington, Sep. 2003.

OBESITY COSTS COMpANIES $13 BIllION A YEAR

012345678

In B

illio

ns

$8

$2.4$1.8

$1

Health Insurance

Costs

paid Sick leave

life Insurance

disability

Waist circumference—an expanding phenomena in the U.S.—is another tool used to determine risk for disease. A waistline larger than 40 inches for men and 35 inches for women is considered unhealthy and a risk factor for disease. As waistlines grow nationwide, so does the number of people entering the “danger zone” for disease.17

No matter what tool is used to measure obesity, the fact is that the accumulation of fat sets people up for chronic diseases, most notably cardiovascular disease, diabetes, certain types of cancer and osteoarthritis. Many of these diseases are correspondingly rising along with obesity and inflating healthcare costs. The costs are incurred by businesses in a number of ways. Consider, for example, that people with diabetes lose more than eight work days a year. Nationwide, this adds up to 14 million disability days.18

The larger the BMI, the higher the costs. Dr. Finkelstein’s research found that the increased costs ranged from $462 for slightly obese men to $2,207 for men with a BMI greater than 40. For women, the range was $1,372-$2,485. When factoring in the additional absences, the range for all obese employees was $460-$2,485.19

HEAlTH RISkS Of OBESITY

Hypertension (high blood pressure)

Type 2 diabetes Coronary heart disease

Stroke Gallbladder disease

Cancer (endometrial, breast, esophagus and colon)

Additional: sleep apnea, osteoarthritis, respiratory problems, infertility, pancreatitis, liver disease, etc.

Source: American Obesity Association.

In simplest terms, obesity is the result of consuming too many calories and getting too little exercise to burn the calories. This “energy imbalance” and the accumulation of fat are not always simply a behavioral issue. There are a host of factors that can contribute to unhealthy fat accumulation ranging from genetic factors, individual metabolism, diseases and medications to cultural influences and even stress and lack of sleep.21

Understanding the Causes

4 Health Advocate, Inc.

Obesity is linked to 400,000 deaths in the U.S. each year.20

Obesity generates more chronic health problems than smoking or heavy alcohol use.22

Despite these factors, “clearly, the epidemic of obesity is primarily due to a combination of the availability of high-calorie foods and a sedentary lifestyle,” says Janine V. Kyrillos, M.D., Director, Preventive Health Care Program and Medical Coordinator, Weight Management Program at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia. Consider that computer and video game “screen” time averages an astonishing eight hours a day in the United States. “The good news is that adopting a healthy diet and exercise can shift the energy balance and is the best area to focus on for prevention and treatment of obesity,” says Dr. Kyrillos.

While each individual is ultimately responsible for taking action to reduce his or her unhealthy weight, workplace intervention can play an important role in contributing to the solution and supporting healthy efforts.

In many ways, the workplace is uniquely positioned to offer solutions to counter unhealthy habits. Typically, an increasing number of employees spend most of their time sitting with little opportunity for movement throughout the day. They have access to too many high calorie snacks in vending machines and too little lunchtime to eat at a healthier pace. It’s a formula that adds up to unhealthy weight gain.

According to a survey published by Chicago-based CareerBuilder.com, nearly half of workers report that they gained weight at their current jobs. Twenty-six percent of employees said they gained more than ten pounds and 12 percent said they gained more than 20 pounds while in their current jobs. Women were more likely (50 percent) than men (42 percent) to say they put on the pounds at their current jobs.23

Employers have an opportunity to change this situation. Indeed, the workplace can be an ideal environment for social reinforcement to encourage behaviors that help employees lose weight.

Intervention is welcomed by employees, studies show. Employees at all weights expressed a willingness to receive employer-based weight loss programs, according to a report issued by the STOP Obesity Alliance operating out of The George Washington University School of Public Health and Health Sciences. Sixty-six percent of survey respondents said they would participate in employer-sponsored gym memberships, nutritional education and weight management programs, for instance.24, 25

5

The Role of Workplace Intervention

Health Advocate, Inc.

Employees welcome employer involvement.

Consider Partnerships

Obesity and the Americans with disabilities Act (AdA)

ADA regulations state that “except in rare circumstances, obesity is not considered a disabling impairment.”

In its ADA compliance manual, the EEOC states that:

“Being overweight, in and of itself, generally is not an impairment. On the other hand, severe obesity, which has been defined as body weight more than 100 percent over the norm is clearly an impairment. In addition, a person with obesity may have an underlying or resultant physiological disorder, such as hypertension or a thyroid disorder. A physiological disorder is an impairment.”Source: Staman, Jennifer. “Obesity Discrimination and the Americans with Disabilities Act.” Congressional Research Service (RS22609). Washington: 22 Feb. 2007.

“When approaching strategies to address obesity, keep in mind that it is inappropriate, discriminatory and stigmatizing to single out individuals,” says Dr. Kyrillos. A certain amount of sensitivity and understanding is crucial. “Obesity should be viewed as a chronic disease and an epidemic and not just an affliction affecting a few individuals. With two-thirds of the US population overweight or obese, solutions cannot be based on the belief that obesity is solely caused by lack of willpower and weakness.”

Programs that include weight loss should be part of an overall wellness effort that focuses on real action steps. “The emphasis should be on making all employees healthier,” says Dr. Kyrillos.

There is a range of interventions from the small and inexpensive to the more substantial, such as fully-equipped onsite fitness facilities, that employers can use and modify according to the needs of their workforce.

Employers can partner with local and state governments and many public agencies offer easy-to-install wellness programs. The State of Minnesota, for example, has created a Healthy Minnesota Workplace Initiative Toolkit that can be used by employers in both the public and private sectors.26

Many health departments, universities or other community resources offer speakers on topics from nutrition and exercise to stress management. Available conference rooms or the cafeteria can

Overall Health is the Primary Goal

Successful Strategies

6 Health Advocate, Inc.

double as meeting rooms for a Weight Watchers group, for example, or for a fitness class led by a trainer from a local gym.

As an example of a successful partnership, the Nebraska Sports Council, Nebraska's Department of Health and Human Services, teamed up with the University of Nebraska Cooperative Extension and Tiger Coaching & Personal Wellness to develop the N-Lighten Nebraska State Employee Wellness Program. Over 800 state employees participated in 2007 and lost more than 1,650 pounds, while logging nearly 150,000 miles in just eight weeks.27

The Healthier Wisconsin Worksite Initiative is another good example of a collaborative approach. The Governor’s Office, the Department of Health and Family Services’ Nutrition and Physical Activity Program and the Governor's Council on Physical Fitness and Health, provided 11 coalitions with funding to assist worksites in setting up wellness programs. The efforts showed significant results in just a short period of time. Fruit and vegetable consumption increased from 7 to 65 percent, depending on the worksite, and weight loss was noted at several sites, including one site that reported weight loss for 34 percent of the participants.28

Employers can check with local health departments or state health agencies or investigate the site, www.mypyramid.gov for resources available to help them address obesity.

A Health Risk Assessment (HRA) is an online questionnaire that includes questions about family and personal medical history, factors like high blood pressure and lifestyle habits such as diet and exercise that impact the development of diseases like heart disease. Learning about their risks for disease may spur employees to participate in wellness programs that can help lower their risks.

Aggregate HRA data can reveal what wellness programs may be the most advantageous for a particular workforce population. For instance, if employees tend to just be somewhat overweight, providing a basic fitness and weight management program may be appropriate. If a sizeable number of employees are obese and not ready for vigorous activities, an initial goal may be raising awareness through nutrition classes about the link between diet and body weight.

These two companies showed that HRAs can be a cost-effective feature of a wellness program:

Daimler Chrysler employees who completed an HRA and then engaged in one additional wellness activity had an average cost savings of over $200 in 1997.29

7Health Advocate, Inc.

Health Risk Assessments

Focusing on Healthier Eating

Bank of America’s wellness program that included an HRA and educational materials showed a ten percent decrease in healthcare costs over a two-year period.30

Biometric screenings that measure BMI, blood pressure and other factors, can help identify specific health issues that employees may need to address. Often employees are unaware they may have high blood pressure or that their weight has reached an unhealthy level. These simple measurements can be powerful predictors of future health problems. If taken before and after participation in a wellness program, they can help measure the program’s effectiveness.

Educating employees through vigorous and ongoing communications about how health issues such as high blood pressure or lifestyle habits such as diet and exercise are linked to weight can play a key role in addressing obesity. Charts, flyers and newsletters can address specific topics such as weight gained from consuming specific snacks or calories burned from everyday physical activities. The goal is to help employees become aware and make the connection between their behaviors and their weight and then provide resources to support actions that modify behavior.31

In the Careerbuilder.com survey cited previously, 45 percent of the employees reported gaining weight. Of this group, 12 percent reported buying their lunch out of a vending machine at least once a week. Sixty-six percent of employees surveyed snack at least once a day and nearly 25 percent snack at least twice a day.32

Another survey reported that nearly three quarters of employees say that they eat unhealthy snacks—chips, candy, etc—at work once a week; 27 percent said they did so three or more times a week.33

There are a number of ways that employers can help employees eat healthier food. Solutions range from switching from soda to water in vending machines, offering yogurt, nuts and popcorn at meetings, and strategic placement of charts listing the calorie content of snack foods. Providing a longer lunchtime can allow employees time to walk or use the gym. Flexible work hours overall can also help.

A study in the May 2004 Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine that studied General Electric workers found that encouraging obese employees to engage in physical activity as little as once or twice a week, may reduce health care costs by roughly $450 per year per employee. According to their findings, researchers

8 Health Advocate, Inc.

Making Activity Accessible

Biometric Screenings

Educational Strategies

estimated that increasing levels of physical activity for sedentary obese workers would have saved about $790,000, or about 1.5 percent of healthcare costs for the whole group of 23,500 workers.34

Encouraging activity throughout the day can help manage weight. This does not necessarily require a gym or even a track around the building. Simple reminders to take the stairs, park further from the door and walk down the hallway instead of emailing can create a sense of being active, instill the movement habit and may motivate employees to take care of their health in additional ways.

Built-in activity breaks. Two, half-hour breaks twice a week could help employees lose weight and also help lower blood pressure, increase energy, decrease back pain, sleep better and better handle stress. All these benefits, plus a rise in productivity may occur after just eight weeks, according to a Baptist Health System study conducted in Mississippi.35

Casual dress days. A University of Wisconsin study found that employees showed an eight percent increase in physical activity levels on casual workdays compared to days when conventional clothing was worn and that they burned an average of 25 additional calories resulting from extra steps. Understandably, not wearing heels or constricting suits can allow for more freedom of movement.36

Additional investments. Memberships or discounts to health clubs, onsite wellness centers, exercise/walking trails and providing bikes are additional strategies that should be keyed to the workforce population.

In one 2007 study, published in Nature Medicine, researchers found a connection between stress, a high calorie diet and an unexpectedly high weight gain. Apparently, stress may unlock the body’s fat cells.37

Helping employees manage stress is an important wellness strategy. A room dedicated for quiet time may be prudent. Offering yoga, tai chi or other slow meditative activities can be other helpful anti-stress strategies.

Stress management may very well lower overall healthcare costs. The U.S. Department of Labor estimates that stress costs businesses $300 billion in lost productivity, absenteeism, accidents and more. A Gallup poll reported that 80 percent of workers feel stress on the job.38

9Health Advocate, Inc.

Stress Management Strategies

Currently, about 25 million U.S. children and adolescents are overweight or obese. Experts at the Mayo Clinic suggest that the most effective way to treat—and prevent—childhood obesity is for the family to adopt healthier habits as a unit.39, 40

IBM has introduced the Children’s Health Rebate, which rewards good nutrition and physical activity for the entire family. The idea is to help children develop healthy habits for a lifetime. Employees use an interactive online tool to manage their family’s eating and exercise habits with self-paced tracking plans that can be securely accessed only by the employee’s family. There are no set weight loss or exercise targets that have to be reached, but families that participate receive a $150 cash rebate.41

Government website links such as MyPyramid.gov and Fitness.gov offer tips and useful information aimed at the family that employers can share with employees.

When it comes to increasing participation and adhering to a specific behavior, incentives can increase follow-through by up to 20 percent, says Sandra J. Wendel, editor of Worksite Wellness Works newsletter produced by the Wellness Councils of America in Omaha. A powerful and simple incentive is to offer wellness programs during work hours which may increase participation, even among the less motivated employees, experts say.

There are dozens of ways employers can reward employees for reaching a weight loss goal. Options include awarding T-shirts and other prizes, paid days off, praise in the company newsletter and even an all-expense paid getaway.42

Cash incentives. Modest financial incentives can produce good results. Participants in one study were offered two levels of financial incentives: $7 and $14 per percentage point of weight lost. Payments were structured so that all participants had an equal ability to obtain the incentives during the study period of 3 months.43

Employees received no structured diet or exercise plan. Yet, after three months:

Employees offered no incentive lost two pounds.

Employees offered seven dollars lost three pounds

Employees offered fourteen dollars lost five pounds.

10 Health Advocate, Inc.

Role of Incentives

Targeting the Entire Family

NEw RulES ANd wEllNESS pROGRAMS

As of 2008, the law:

�Prohibits a group health plan or group health insurance issuer from denying individual eligibility for benefits based on a health factor or from charging an individual a higher premium than a similarly situated individual based on a health factor.

�Allows discounts for participation in wellness, but are capped at 20 percent of a single employee’s insurance premium.

Stipulates that employers must provide a “reasonable alternative” in their wellness policies for people who have physical or medical conditions that limit their ability to participate in the program(s).

Source: U.S. Department of Labor. “Field Assistance Bulletin No.” 2008-02. 14 Feb. 2008.

The Nordam Group, an aircraft parts and service company in Tulsa, Oklahoma, pays as much as $300 in incentives to employees for losing weight and quitting smoking and also offers a lowered fee to join the local YMCA. They have estimated that for every $1 they spend on their wellness program, they get an ROI of $2.50 to $6.00.44

Personalized wellness coaching. Wellness coaches can be one of the best incentives, according to Harris HealthTrends’ John Harris. “People try harder and do better when they’re ‘playing’ for a coach. You don’t want to let your coach down.” He claims enrollment rates of up to 93 percent for programs that provide a personal wellness coach.45

Long-term commitment. “Employers, as a group, are notoriously short-term thinkers, but there is no quick fix,” notes Ronald J. Ozminkowski, Vice President of Research and Development at Ingenix, a Minnesota healthcare information and research firm, who has researched the impact of chronic disease on corporate profits. His advice to wellness planners: “If you think you can have a weight-loss program today but not one next year, you’re flat wrong.”46

A few companies offer a controversial, “mandatory weight loss” policy for participation in wellness programs. Some insurance companies have developed health plans with significantly high deductibles for employees. Those who meet weight, blood pressure

11Health Advocate, Inc.

Penalties vs. Rewards

and cholesterol goals and do not smoke can have a significant decrease in their deductibles. However, penalizing employees to change their behavior raises a host of legal, moral and practical questions. It may be more prudent to take the positive approach and offer incentives to support weight loss and health efforts.47

Existing employer-based weight loss programs are typically—and appropriately—part of an overall wellness program, and therefore, few studies exist that measure their impact separately from their inclusion in these more comprehensive programs.

A recent review, however, reported in the American Journal of Health Promotion (July/August 2008) has revealed intriguing data. Researchers reviewed nearly a dozen workplace wellness intervention studies since 1994 including some that were updated in 2006. The interventions varied and included HRAs, email and face-to-face wellness counseling, onsite exercise sessions, healthy cafeteria food and nutritional information. Most of the programs involved education and counseling to improve diet and exercise. All lasted at least eight weeks and involved workers aged 32 to 52. BMIs or weights were taken before and after the intervention.

On average, the participants lost 2 to 14 pounds compared to non-participants. “For people who participate in them, work site- based programs tend to result in weight loss,” says researcher Michael Benedict, MD, from the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine.48

Surveys show that nearly one-fourth of the nation’s employers buy into the idea of workplace solutions to address obesity. Several companies have emerged as good examples of how a well thought-out wellness program can help employees adopt healthier habits to lose weight and reduce healthcare costs.49

According to company figures, seventy percent of IBM employees participate in physical activity intervention annually, with a reported increase in physical activity from year-to-year compared to non-participants. Additionally, employees who participate in the company’s web-based nutrition and weight management program showed increased healthy eating habits six months into the program. Participants consumed 20 percent less junk food and ten percent more fruits and vegetables. Those reaching their normal weight increased nine percent versus one percent for nonparticipants.50

12 Health Advocate, Inc.

IBM

Success Stories

Reward employees for small changes.

“Addressing obesity requires individuals to make a lifestyle change. Even 10 percent weight loss is considered successful—and realistic.”

14 Health Advocate, Inc.

The Department increased indoor fitness areas from 14 to 22 worksites, made healthy vending and meal options available at 24 sites, developed healthy food policies for agency events and created policies to support employees for being more physically active in the workplace. Out of the 4,788 employees who were surveyed, more than 60 percent participated in a worksite wellness activity. Forty-five percent reported walking and/or exercising more often than in prior years; 46 percent said they were choosing healthier snacks/meals more often; 33 percent were eating fewer high-fat foods and 23 percent reported moving closer to a healthy weight.51

Since 2004, the company offered employees a $260 contribution to their health care premiums if they took a health risk assessment and participated in wellness screening. In 2006, the company found the difference in medical claims and drug costs for participants was $720 less than it was for nonparticipants. More recently, since 2007, employees and their spouses who engage in the program receive a benefit credit and have access to health coaches as well. As a result, more than 92 percent of Crown Equipment employees participate in the program. The company is also providing healthier vending programs and healthy snacks during breaks. Today, more than half of their workforce falls into the low health risk category—an improvement of 12 percent.52, 53

BARIATRIC SuRGERY

Gastric bypass surgery has been shown to be an option that is effective for BMI over 40 (or, 100 pounds overweight). Emerging studies indicate that surgery is even beneficial for individuals with a BMI over 35 who have co-morbidity conditions such as Type 2 diabetes. There is also some emerging evidence that bariatric surgery—which is being covered by more insurance companies when medically necessary—may pay for itself. Employees who have had the surgery had fewer sick days, for instance.54

A new wave of innovations promise to help employers encourage activity without sacrificing productivity. A groundbreaking six month study called NEAT (stands for Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis) was conducted by James Levine, M.D., an endocrinologist at the Mayo Clinic, at a financial staffing company in Minneapolis. Forty-five

Crown Equipment Company

On the Frontier

North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services

15Health Advocate, Inc.

employees volunteered to work in a re-engineered office setting that included walking tracks, walking meetings, traditional phones replaced with mobile sets, nutritional information and even desks outfitted with treadmills. After six months, 18 participants lost a total of 156 pounds. Monthly revenue rose to 10 percent at the study’s midpoint.55

On a smaller scale, innovations such as under-the-desk pedal devices, for example, may help support a “culture of fitness and health” at the workplace and, in turn, could help reduce obesity.

Whether you invest in something relatively simple such as posted dietary tips, a room for Weight Watchers meetings, a wellness coach or a full-scale, onsite gym or outside track—it’s important to acknowledge that addressing obesity requires individuals to make a lifestyle change. Companies should not expect instantaneous results. Even a ten percent weight loss is considered successful—and realistic. A modest weight loss of 5-15 percent of body weight can significantly help manage obesity-related conditions.56

The key to success is to make weight loss part of a wellness program that has these main features:

�A well-planned, long-range strategy, customized to your organization

�Commitment from all senior management

�Built-in time tables and achievable goals

�Provide multiple approaches and a vigorous communications campaign

�Offer incentives and rewards for even small changes

Again, overall improvement of health is the ultimate goal. If employees are unable to lose weight, they can still exercise, stop smoking and manage stress. These actions can help reduce risks for chronic diseases, curb absenteeism, create healthier, more productive employees—and lower healthcare costs.

Support is Key

16 Health Advocate, Inc.

1 The Endocrine Society and The Hormone Foundation. The Endocrine Society Weighs In: A Handbook on Obesity in America. May 2004.

2 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Preventing Obesity and Chronic Diseases Through Good Nutrition and Physical Activity.” 15 Sep. 2008. http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/publications/factsheets/prevention/obesity.htm.

3 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity Among Adults: United States, 2003 – 2004.” 9 Sep. 2008. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/pubs/pubd/hestats/overweight/overwght_adult_03.htm.

4 Walker, Emily, “Rising Tide of Obesity in America Continues Unabated.,” Medpage Today 20 Aug. 2008.

5 Partnership to Fight Chronic Disease. “About the Crisis – Chronic Diseases Are Creating a National Health Care Crisis.”

6 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Chronic Diseases – Introduction.” 20 Mar. 2008. http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/overview.htm.

7 Partnership to Fight Chronic Disease, “An Unhealthy Truth: Rising Rates of Chronic Disease and the Future of Health in America.”

8 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. “Prevention Makes Common ‘Cents’.” Washington: Sep. 2003. http://aspe.hhs.gov/health/prevention.

9 Id.

10 “Obesity and Disability.” RAND Health. 2007. http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB9043-1/index1.html.

11 Hellmich, Nanci. “Financial Incentives Can Encourage Weight Loss, Research Finds.” USA Today 11 Sep. 2007.

12 “UnumProvident Report Shows Tenfold Increase in Obesity-Related Disability Claims,” Unum. Press Release: 17 Feb. 2004.

13 Ostbye, Truls M.D., Ph.D., et. al. “Obesity and Workers’ Compensation: Results From the Duke Health and Safety Surveillance System,” Archives of Internal Medicine 167.8 (23 Apr. 2007):766-773.

14 Bundorf, M.K., and Bhattacharya J. “The Incidence of the Health Care Costs of Obesity.” Abstract AcademyHealth Meeting 21 (2004): abstract no. 1329.

15 A.M. Best. “A Weighty Issue.” Best’s Review June 2008.

16 Sturm, Roland. “The Effects of Obesity, Smoking, and Drinking on Medical Problems and Costs.” Health Affairs 21.2 (Mar./Apr. 2002): 245-253.

17 NIH National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults. Washington: Sep. 1998.

18 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. “Prevention Makes Common ‘Cents’.” Washington: Sep. 2003. http://aspe.hhs.gov/health/prevention.

19 Hellmich, Nanci. “Heavy Workers, Hefty Price.” USA Today 11 Sep. 2005.

20 The Endocrine Society and The Hormone Foundation. The Endocrine Society Weighs In: A Handbook on Obesity in America. May 2004.

21 Id.

22 Sturm, Roland. “The Effects of Obesity, Smoking, and Drinking on Medical Problems and Costs.” Health Affairs 21.2 (Mar./Apr. 2002): 245-253.

23 “Survey: 45% of Employees Gain Weight.” Pacific Business News (Honolulu) 14 May 2008.

24 Strategies To Overcome & Prevent Obesity (STOP) Alliance. “Costs Driving Employer Action Against Obesity.” January 2008. Survey by National Opinion Research Center at the U. of Chicago and George Washington U. School of Public Health and Health Services. http://www.stopobesityalliance.org/insights.htm.

25 Nationwide Better HealthTM. “As Obesity Rates Continue to Rise, Is the Workplace a Source of or Solution to Unhealthy Lifestyle Habits?” 17 Sep. 2007. http://www.businesswire.com/news/google/20070917005154/en.

26 Minnesota Department of Health. “Healthy Minnesota Workplace Initiative.” Sep. 2007. http://www.health.state.mn.us/divs/hpcd/chp/worksite/index.htm.

27 Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services. “State Employee Wellness Program Produces Results.” Dec. 2007. http://www.hhs.state.ne.us/newsroom/newsreleases/2007/Dec/wellness.htm.

28 Department of Health and Family Services, Wisconsin Nutrition and Physical Activity Program. “Healthier Wisconsin Worksite Initiative 2007 Summary Report.” (n.d.).

29 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. “Prevention Makes Common ‘Cents’.” Washington: Sep. 2003. http://aspe.hhs.gov/health/prevention.

30 Fries, J.F., et. al. “Two-Year Results of a Randomized Controlled Trail of a Health Promotion Program in a Retiree Population: The Bank of America Study.” The American Journal of Medicine 94 (1993):455-62.

31 Kahn, Emily B., Ph.D., M.P.H., et. al. “The Effectiveness of Interventions to Increase Physical Activity.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 22 (2002):4S.

32 “Survey: 45% of Employees Gain Weight.” Pacific Business News (Honolulu) 14 May 2008.

33 Nationwide Better HealthTM. “As Obesity Rates Continue to Rise, Is the Workplace a Source of or Solution to Unhealthy Lifestyle Habits?” 17 Sep. 2007. http://www.businesswire.com/news/google/20070917005154/en.

34 Wang, Feifei, Ph.D., et. al. “Relationship of Body Mass Index and Physical Activity to Health Care Costs Among Employees.” Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 46.5 (May 2004):428-436.

35 Beason, Sandy. “Finding Time for Workplace Fitness.” Get Fit Mississippi Jul. 2008.

36 “ACE Study Finds Fitness Benefits of Wearing Casual Clothing to Work: Casual and Comfortable Clothing Workdays Promote Increased Physical Activity.” American Council on Exercise. Press Release: 12 Jul. 2004.

37 Kuo, L., et. al. “Neuropeptide Y Acts Directly in

the Periphery of Fat Tissue and Mediates Stress-Induced Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome.” Nature Medicine 13 (2007):803-811.

38 “Job Stress.” The American Institute of Stress. 2007. www.stress.org.

39 “Childhood Obesity: Make Weight Loss a Family Affair.” Mayo Clinic. 28 Jun. 2008.

40 NIH, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. “Working Group Report on Future Research Directions in Childhood Obesity Prevention and Treatment.” 21 Aug. 2007. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/meetings/workshops/child-obesity/index.htm.

41 “IBM's New Children's Health Rebate for Employees Helps Families Attain a Healthy Lifestyle.” IBM. Press Release: 24 Oct. 2007.

42 Madlin, Nancy. “Wellness Incentives: How Well Do They Work? Companies Are Offering Everything From Green Stamps to Days Off in Order to Get Participation.” Business & Health Apr. 1991.

43 Rosenwald, Michael S. “An Economy of Scales.” The Washington Post 11 Nov. 2007.

44 Levi, Jeffrey, Ph.D., et. al. F as in Fat: How Obesity Policies Are Failing in America. Trust for America’s Health. Aug. 2007.

45 McCarthy, R. “Who’s in Charge of Health?” Business & Health Institute. 2002.

46 “From Incentives to Penalties: How Far Should Employers Go to Reduce Workplace Obesity?” Knowledge@Wharton. Wharton, U. of Pennsylvania. 9 Jan. 2008.

47 Id.

48 Colihan, Kelley. “Workplace Programs Help Shed Pounds.” WebMD Health News 30 Jun. 2008.

49 Levi, Jeffrey, Ph.D., et. al. F as in Fat: How Obesity Policies Are Failing in America. Trust for America’s Health. Aug. 2007. http://healthyamericans.org/reports/obesity2007/Obesity2007Report.

50 “2008 Koop Award Winner: Wellness for Life – International Business Machines.” C. Everett Koop National Health Awards. (n.d.) http://healthproject.stanford.edu/koop/IBM%202008/evaluation.html.

51 Levi, Jeffrey, Ph.D., et. al. F as in Fat: How Obesity Policies Are Failing in America. Trust for America’s Health. Aug. 2007. http://healthyamericans.org/reports/obesity2007/Obesity2007Report.

52 “Employers Offering Incentives for Workers to Improve Health.” Financial Advisor 8 Nov. 2007.

53 “Crown Equipment Corporation Leader in Next Generation Health Management Program.” Crown Equipment Corporation. Press release: 14 Nov. 2007.

54 “Studies Say Obesity Surgery Prolongs Lives.” CBS News 23 Aug. 2007.

55 Farnsworth, Amy. “’Treadmill Desks,’ Company-Sponsored or Home-Built, Energize the Desk-Bound.” Christian Science Monitor 8 Aug. 2008.

56 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. “Overweight and Obesity – Health Consequences.” The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent and Decrease Overweight and Obesity. Washington: 11 Jan. 2007. http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/topics/obesity/calltoaction/fact_consequences.htm.

footnotes