NU Asian Magazine

-

Upload

nu-asian-magazine -

Category

Documents

-

view

229 -

download

0

description

Transcript of NU Asian Magazine

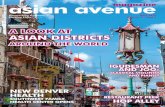

nuAsianspring 2009

volume 5 issue 1an APAC publication

INSIDE: A trip to Chicago’s Asian American neighborhoods

RachaelYamagata

A look at the‘Model Minority’

MythExploring its origins

Does it exist at Northwestern?

Funded by SAFB

The NU alumna andsinger-songwriter on beingAsian American

editor’s note“What are you?”“Where are you from?”“What’s your background?

These are all really simple questions, but somehow they always evoke really complex answers. My immediate reac-tion is usually to start talking about what my major is, and then to continue on with how I was born in Boston but now live near Washington, D.C. — but those are usually not the answers people want to hear.

“But what are you?”

“I’m Asian American; ethnically, I’m Chinese.”

Ah, that’s the ticket.

But surprisingly, that’s rarely the first answer that comes to mind when I’m asked that question.

Even when I do give people the answer they’re looking for — that I’m of Chinese descent — it’s often followed by, “Well, my dad was born in Hong Kong, but my mom was born in Wyoming, and I was born in Boston...” Before I realize it, my answer becomes even more muddled.

In many ways, that’s the beauty of individuality.The way we define ourselves is a product of so many vary-

ing factors. To limit our answer to one or two words does little justice, especially in the 21st century when the term “Asian American” means many different things to many dif-ferent people.

Whether we’re of mixed ethnicities or of full Asian de-scent, whether we were born in the States or born overseas, or whether we’re first-generation or third-generation Ameri-cans, we, as Asian Americans, compose a diverse group of individuals. The term “Asian American” does not fit squarely into a box, and we can’t use it to reflect one type of person or one stereotype.

This magazine issue explores the idea of redefining what it means to be Asian American in the 21st century and cel-ebrates the diverse Asian American population. From actors to athletes, pediatricians to politicians, and bakers to bank-ers, Asian Americans today are breaking boundaries.

Check out our “Soapbox” spread (p. 23) to see how students at Northwestern view the term “Asian American,” and read about NU alumna Rachael Yamagata (p. 6) and her views on being an Asian American.

As always, thanks for reading. Enjoy!

2 nuAsian spring 2009

Ashley LauAshley LauEditor-in-Chief

Magazine Staff2008-2009

nuAsianNorthwestern University’s APA Magazine

Volume 5 - Issue 1 - Spring 2009

http://groups.northwestern.edu/apac/

apacNU’s Asian Pacific American Coalition

&

Funded by the Student Activities Finance Board

EditorialAshley Lau, Editor

Iris KimNancy Lee

Kaixi OuyangNathalie TadenaSamuel Wheeler

DesignPong Chakthranont

Emily ChowJohn GrayAshley LauMichelle LiuMelissa LuKatie Park

APAC Executive Board2008-2009

David Ma, Co-PresidentKaixi Ouyang, Co-President

Joe Lee, Vice PresidentCatherine Wu, Treasurer

Amy Chen, SecretaryAmy Zhu, Programming Chair

Diana Yu, Communication ChairJoe Spiro, Education Chair

Ashley Lau, Publication Chair

Advisor:Tedd Vanadilok

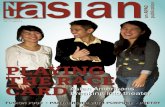

On the cover: Singer-songwriter Rachael Yamagata (Communication ‘97). Photograph by Hilary Walsh.

An extra note:Next fall, I’ll be studying abroad in France — and so this will be my last issue with magazine. While I’m sad to be leaving the publication, I’m happy to introduce next year’s editor, the very capable Nathalie Tadena, who has a lot of great ideas planned for NuAsian. Please feel free to get in touch with her ([email protected]) to find out how you can get involved with the magazine!

3nuAsianspring 2009

4

17

98

6

2322

19

12

insideTHe AMeRiCAniZATiOn OF AsiAn FOOd

ALUMnA PROFiLe: RACHAeL YAMAGATA

sPOTLiGHT CHiCAGO: BUddHisT TeMPLe

FindinG THe AsiAn AMeRiCAn VOTe

A WALK THROUGH CHiCAGO’s CHinATOWn

THe FACes OF CAFÉ JK sWeeT

THe MOdeL MinORiTY MYTH

COLUMn: AsiAn AMeRiCAns in THe WORKPLACe

sOAPBOX

What many consider to be “Chinese food,” or Asian food in general, is usually an Americanized form of an original dish. One writer traces the history of Asian food in America from its traditional roots to what we now see in restaurants today.

NU alumna Rachael Yamagata (Communication ‘97) talks about her journey from being a Northwestern student to a successful singer-songwriter, also re-flecting on what it means to be Asian American.

The Buddhist Society for Compassionate Wisdom (BSCW) on the North Side is one of only five BSCW temples in the western hemisphere. Besides its grand presence, it serves as an important symbol of Asian American culture in Chicago.

Among voters identifying themselves as individuals of color, African Americans saw a voter turnout increase of 22 percent and Latinos an increase of 16 per-cent. Asian Americans, however, saw an increase of only 3 percent.

Freshman Samuel Wheeler, new to Chicago, takes a notepad and pen down to Chicago’s Chinatown to chronicle his first visit in one of the city’s largest Asian-American neighborhoods.

At the heart of J.K. Sweet are the Shims: a husband-and-wife duo that recently took over the multi-purpose café after the longtime owner retired. The two share their experiences serving the Northwestern community.

The commonly-held belief that Asian Americans are better off academically, financially and professionally compared to other groups traces its origins to the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. Where does this “myth” stand today?

One writer reflects on the barriers of Asian Americans in the workplace, drawing on her experience as an Asian American interning at Lehman Brothers this past summer.

What does it mean to be Asian American in the 21st century? Find out what Northwestern students think about the term “Asian American” and how the term is being redefined.

Americanization of Asian Food, 4

A Walk Through Chicago’s Chinatown, 12

Rachael Yamagata, 6

By the 1920s, Asian cuisine was considered exotic by many young cosmopolitans. Authentic Cantonese

restaurants began offering two menus. One menu was available for Asian customers who were used to the

Cantonese tradition of stir-fry, rice based dishes that utilized every part of the animal, such as duck feet. A

second menu modified traditional dishes to accommo-date an American palate, often relying on basic meat

and vegetable dishes served in standard sauces , such as sweet and sour or soy, with fried rice. Many Chi-

nese restaurants concocted dishes like won ton soup, egg rolls, barbecued spareribs and beef with lobster

sauce to appease American customers.

After WWII, Asian cuisines became more mainstream for American diners. Political interactions with dif-ferent regions of China influenced many Americans

to attend classes to learn Chinese cooking styles other than Cantonese. New restaurants started to specialize

in Mandarin, Hunan, Fukien, and Szechwan dishes.

5nuAsianspring 2009

In the 1970s, other Asian cuisine like Vietnamese and Thai food gained popularity in the US, leading to the birth of fusion cuisine—a contem-porary mixture of traditional Asian culinary styles with European dishes. Many chefs turned to fusion cuisine as a way to modernize traditional menus and compete with other res-taurants. Early fusion dishes pulled Indian, Thai, Chinese, Vietnamese and French inspirations.

In the 1950s and 1960s, as Ameri-cans began moving to suburban com-munities, Chinese restaurants began opening in shopping malls, offering cheap delivery service known as “take out.” In the 1960s, Polynesian themed restaurants and tiki bars also became popular.

In the 1900s, “chop suey” houses were built in New York, Boston, Washington, Philadelphia and Chicago after Li Hongzhang, a top Chinese official visited the U.S.

by Nathalie Tadena

In 1847, the first Chinese immigrants settled in San Francisco, later followed by thousands of Chinese

railroad workers. In the mid-1800s, Europeans first begin trading with China, opening up the seaport of Canton. The Cantonese were the first to emigrate to

Europe and America, and also the first to establish Chinese restaurants outside of China. In California,

where many Cantonese settled, Chinese food was initially only consumed by the Chinese community.

Chinese communities clustered in Chinatown neigh-borhoods in major cities, opening their own “chow

chow eateries” catering to Asian customers. Chinese eateries gained popularity among Americans who

ventured into Chinatown.

7nuAsianspring 2009

by Nancy Lee

Rachael Yamagataalumna profile

Her songs have been featured featured on popular TV shows like One Tree Hill, The O.C., and How I Met Your Mother. But before singer-songwriter Rachael Yamagata, 31, achieved musical success, she said she too was once

your typical Northwestern University student who “hung out at Norris every day.”

Yamagata, who graduated in 1997 with a bachelor’s degree in theatre, said she “barely skirted by” when she was in school. She described college as a generally overwhelming experi-

ence and spoke honestly about her years at Northwestern.

“I can’t say that I had the best experi-ence of my life,” she said. “But, I think that

however it happened, it led me to the best career I could’ve chosen. So there was something about how everything came together that was really very ‘meant to be’ for me.”

During her junior year, Yamagata joined Bum-pus, a Chicago-based band. While working with

the band, a record company scouted her and her solo career followed suit. Her first full-

length album, Happenstance, was released in June 2004 and it garnered hits like “Be Be Your Love” and “Reason Why.” Four years later, on October 7, 2008, Rachael Yamagata returned with her second studio album Elephants…Teeth Sinking Into Heart. The two disc release show-cases an edgier, rock-influenced sound in addition to her signature ballads.

“My writing had progressed to this more poetic lyric, and I wanted the music to be cinematic and lush, and reflect that. So I think that, in itself, started redefining what I had done before because I was taking it to the next level,” she said.

Born to a Japanese father and German-Italian mother, Rachael Yamagata is one of the few mixed Asian American entertainers who have ‘made it’ in the music

industry. Although she couldn’t recall any instances in which

she was discriminated against as a mixed Asian

American figure, early on in her career, she said that there was some

discussion on how to market her ‘Asian’ image.“I think there was a time in the beginning where peo-

ple were wondering, ‘I wonder if they’ll make her change her name or highlight her exotic looks or whatever’ and draw tremendous attention to it either way,” she said.

However, she said the issue never came up thereafter. She also said that while her mixed race is something she embraces, she is hesitant to be portrayed as a representa-tive for any specific race.

“I love my cultural background and being an Asian American, but I don’t want to misrepresent anybody. I haven’t aligned myself with any particular group. I’m really one of the wanderers that kind of weave in and out all over the place.”

She added, “It’s just that I also don’t want to be a fraud. There are so many people that do have hard experiences from being in a minority group, which I have just not had or I have not registered. So, I’m very careful about talking about it in any way that comes off as too much of a calling card. I want to appreciate it without exploiting it.”

Instead, she said she feels more comfortable repre-senting other apsects of herself.

“For me, it’s more maybe as a woman, or maybe as a half-Asian, or maybe as just a reckless weirdo in general.”

Her adaptability and resistance to being pigeonholed can be attributed to the family dynamics she was exposed to growing up. Although Yamagata described her child-hood and upbringing in the Maryland, Washington D.C. area as “pretty run-of-the-mill,” she was essentially raised by four parents. Her parents divorced when she was two and they both remarried. Yamagata said the influence of four parents enabled her to relate to all dif-ferent kinds of people.

“Growing up with four parents who were from such different backgrounds, four archetypes, in a way, it im-mediately made me feel very comfortable with anyone in any situation,” she said.

“In some ways, I think I’ve had an advantage of being surrounded by a lot of strong cultures, and I have been all my life. I identify with all of them. In my experience growing up, I think I was lucky in that I never felt pin-pointed as any one of those things.”

Rather than identify herself in terms of race, Yamaga-ta preferred to characterize herself in other ways.

“I’d say romantic before anything else, logical roman-tic,” Yamagata said. “I don’t think in those terms. I guess you could say I’m an Asian American, you could say I’m a German Italian. I don’t think of myself in that way. Not in a way I don’t think I’m a part of that. I would describe myself in other ways.”

spotlight chicago

8 nuAsian spring 2009

riginally founded as the Zen Lotus Society in 1967, the Buddhist Society for Compassionate Wisdom (BSCW) has now become the North American Buddhist Order.

The North Side Chicago temple is one of only five BSCW tem-ples in the western hemisphere. The founder, Venerable Samu Sunim, has expanded the BSCW to the countries of the United States, Canada and Mexico. According to the temple’s web site, zenbuddhisttemplechicago.org, BSCW follows a modern-day renewal and reapplication of the five major pronouncements of Mahayana teachings:

1. All sentient beings are Buddhas.2. Samsara is Nirvana.3. One’s passions are enlightenment.4. We are an interrelated whole.5. Everyday life is the Way.

The Chicago Temple was first opened in 1992 after a two-year volunteer led renovation process. The member services are held on Wednesdays at 4 p.m. and the free public services are held on Sundays at 9:30 a.m. and 4 p.m. The 4 p.m. service is gener-ally for the less experienced mediator. If you have children, fear not, because there is a children’s service held each Sunday morning at 10 a.m. The Chicago BSCW Temple is dedicated to provide services such as meditation practices, retreats, Bud-dhist education, and other community involved functions throughout the year.

O

by Samuel Wheeler

Location:1710 W. Cornelia Avenue Chicago, IL 60657, USA

Phone:(773)528-8685

On the Web:www. zenbuddhisttemplechicago.org

BUDDHIST SOCIETY for

COMPASSIONATE WISDOM

Map courtesy of Google Maps

Photo courtesy of Nat Krause

9nuAsianspring 2009

The success story of Barack Obama, the first African-American to be elected president of the U.S., has helped shed light on the growing presence of minorities in the American political process.

While Obama’s popularity among students may have contributed to a nine-percent increase in voter turnout among 18 to 29-year-olds, the minority community saw the greatest gains in voter turnout rate overall in this year’s election. According to a study released by Project Vote, the 2008 minority voter turnout increased 21 percent from the 2004 election.

But among voters identifying themselves as individuals of color, African Americans saw a voter turnout increase of 22 percent and Latinos an increase of 16 percent. Asian Americans however, saw an increase of only 3 percent.

So, where are the Asian voters?

Finding the Asian American Voteby Nathalie Tadena

10 nuAsian spring 2009

Asian Americans have had steady rates of political participation for years, but they are often misconceived as a politically apathetic group, said professor Ji-Yeon Yuh, director of Northwestern’s Asian American studies program.

“American stereotypes about Asians being passive have no bearing in reality,” she said. “If Asians were so culturally passive and so culturally undemocratic then it’s impossible to explain democratic movements in South Korea, the Philippines, Burma and India.”

Political Leadership

Asian Americans have been involved in U.S. government for decades—the first Asian U.S. congressmen and senators were elected in the 1950s. Today, there are more than 2,000 Asian and Pacific Islanders serving in elected and appointed positions on local, state and

federal government levels, as reported by UCLA’s AsiaAmerican Studies Center.

Among the more commonly recognized politicians are Louisiana

governor Bobby Jindal, the first Indian-American governor, and California congressman Mike Honda, now chair of the Congressional Asian Pacific American

Caucus. President Obama has also appointed three Asian Americans to his cabinet—Secretary of Energy Steven Chu, Secretary of Veteran Affairs Eric Shinseki and cabinet secretary Chris Lu.

But in spite of these individuals, Asian Americans still hold a smaller proportion of elected political positions in relation to their population size. Although all of the Asian-American incumbents won re-election to their respective congressional seats in the 2008 election cycle, none of the Asian American political newcomers were victorious in their congressional races.

The general absence of high-profile Asian American politicians may deter the community from

Asian Americans have been involved in U.S. government for decades, but they still hold a smaller proportion of elected political positions in relation to their population size.

Voters by race in 2006White

Black

Asian/PI

Latino

Other

Percent of eligible voter population

Percent of votersPercent of registrations Information courtesy of projectvote.org

11nuAsianspring 2009

getting more involved, some say. “You don’t see many Asians in politics,”

Lai said. “There’s no real person that really can be representative of Asians.”

However, voter turnout rates indicate that political involvement among Asians is on the rise. This may be partially attributed to the number of immigrants becoming citizens, an increase in political coverage by ethnic media outlets, and a growth in voter education programs.

“It’s a big problem when candidates address African-American issues or Hispanic/Latino issues but Asian-American issues are often overlooked,” said Weinberg junior Allie Morales. “It’s a reason people may choose not to vote if candidates do not address ways to solve their concerns.”

As part of an internship project with Northwestern’s Asian/Asian American Student Affairs office, Morales researched the polling patterns of Asian Americans nationwide. In an effort to raise the general voter turnout rates of Asian Americans, Morales decided to first reach out to college students and helped organize a campus-wide voter registration drive last fall called NU Decides.

Morales said that the candidacy and eventual victory of a candidate with Obama’s background made this past election “historic.” But, there is still more that can be done to address issues of particular concern to the Asian American community, such as immigration laws and economic policies.

“It’s been one step forward because both candidates addressed all different minority groups, but there still wasn’t equal attention,” she said.

Political Leanings

A 2008 poll conducted by The Institute of Politics at Harvard University found that among Asian-Americans aged 18-24, 47 percent identified themselves as a Democrat, 15 percent as Republican and

39 percent as Independent. Asian Americans’

concern with labor immigration rights

have made them empathetic to some of the Democratic party’s stances, but Asian Americans should not be viewed as an overwhelmingly democratic group, Yuh said.

“Politicians don’t really pay a lot of attention to us as a voting block, they don’t really know what to make of us,” she said. “They’re not sure if we’re Republican or Democrat, they think of us as being a tiny minority.”

The failure to capitalize on the Asian American vote “has a lot to do with Asian Americans conceptualized as not just as different race, as not even Americans, as foreign,” Yuh added.

Asian Americans constitute approximately 4 percent of the U.S. population, though the U.S. Census predicts the population will rise to 8 percent by 2050. Yuh said that

political campaigns often focus more on other demographic groups with more predictable voting patterns, citing the Jewish electorate—who also make up approximately 4 percent of the U.S. vote—as heavily targeted by the Democratic party.

“Asians are leaning democratic but still have a significant Republican constituency,” she said. “They should be seen as a significant swing vote, courted by both parties.”

In the 2008 election, while an overwhelming 62 percent of Asian Americans voted in favor of Obama, Asian-Americans also had the highest rates of voting Republican among minority groups. Obama’s Republican rival John McCain received 35% of the Asian vote, compared to 31% of the Latino vote and 4% of the African-American vote.

Music freshman Danny Lai said he

supported Republican John McCain over Obama in the election for reasons unrelated to Lai’s background.

“Obama seems questionable because of his inexperience, which means we don’t know anything about what his policies will be like and because of the personality cult that developed around him,” Lai said.

Medill sophomore Sisi Tang emigrated from China but grew up in Pittsburgh. She said she considers herself an independent.

“My parents weren’t involved in the political scene since they’re not from here. They didn’t know enough about American culture to be involved with it,” Tang said. “But I haven’t been affected by their points of view and I was able to develop my own point of view.”

Like Tang, first generation children of immigrants and individuals who grew up in the U.S. are likelier to be more knowledgeable about politics.

Weinberg sophomore Cindy Wu said that among her friends with Asian backgrounds, those who are first generation children of immigrants were more interested in going into the political field. “I don’t think race necessarily has anything to do with it, they’re either really in to politics or not,” Wu said. “But growing up in American culture, you’re more American and it’s easier to fit in.”

But some say that continuing to encourage political participation may help dispel misconceptions about Asian Americans.

“Stereotypes arise out of our particular minority status,” Yuh said. “Until we can change our minority status, we’re not going to be able to change stereotypes. But we shouldn’t really be focusing on combating stereotypes, but on trying to increase our own empowerment.”

“Politicians don’t really pay a lot of attention to us as a voting block, they don’t really know what to make of us.... They think of us as being a tiny minority.”

- Ji-Yeon Yuh

A

efore stepping foot on the Chinatown square in Chicago, I had virtually no cultural knowledge of the area. On one hand, I was excited to immerge myself into this seemingly

foreign city. But on the other, I had no idea where to begin. I was about to embark on a journey to understand how a person unfamiliar with the city’s subcultures, could understand enough to write a piece about the rich environment Chinatown has to offer. I spent a couple days researching, and on a brisk Chicago winter night, I stepped off the Cermak El stop and walked into an unknown world.

B

13nuAsianspring 2009

Photo courtesy of Daniel Schwen

According to the 2000 U.S. census, there are currently 68,000 Chinese in the Chica-goland area and Chinatown Chicago is the second largest in the nation. The eight blocks of Chinatown are nestled between the northern border of 18th street, 26th street to the south, the el to the east, and the Dan Ryan expressway to the west. Of course these are not official boundaries, but the culture of Chinatown is very well preserved within this location. One interesting fact however, is that the current Chinatown has not always been the spot for Chinese immigrants to assimilate into American culture.

According to a Chinatown Web site, the first Chinese immigrants arrived in Chicago in the 1870s, after completing the first transcontinental railroad. Among them was Chinese pioneer T.C. Moy, who settled in Chicago in 1878. Facing strict laws that kept Chinese immigrants to a minimum, T.C. Moy encouraged family members and friends to come to the city and start new lives. At that time, Immi-grant workers in Chicago were the cause of much discrimination. The Chinese immigrants started what were considered

innocent occupations such as restaurant owners and small businesses. By 1900, 167 Chinese-operated restaurants existed in the city.

Chicago’s first Chinese community, established in 1905, was built near Van Buren and Clark Street. At the time, the new influx of Chinese residents caused alarm and discrimination from the current non-Asian residents. Landlords raised

rent prices for im-migrants, forcing them to move to the current Chinatown location at Cermak and Wentworth. Through a series of available leases, this relocation was contracted and made possible by the H.O. Stone Company and members of the On Leong Business-men’s Association. The area grew over the next century and the larg-est influx of Chinese immigrants arrived shortly after in the 50s and 60s.

When I first stepped off the El and laid eyes on Chinatown I was amazed. I had no idea that such a rich culture was still preserved in the modern age. I decided to walk around and take in as much of the culture as I could. The Chinatown Gate, with its breathtaking hand-painted tiles, was the first structure to catch my eye. Although I couldn’t read the four giant Chinese characters on the gate, I knew that the red gate must have symbolized a new beginning for the Chinese people. It turns out that the characters read, “The world belongs to the commonwealth.” Accord-ing to ChicagoChinatown.org, the idea of a gate was conceived by George Cheung, a civic promoter, and designed by architect Peter Fung in 1975. The saying on the gate reflects the ideas of Chinese people that are based around community drive for the common good. As far as I could tell, the gate fits in perfectly with the surrounding architecture.

Most of Chinatown’s attractions are the result of the creation of the Chicago Chinatown Chamber of Commerce in 1983. According to the website, the mission is to “improve and expand business opportuni-ties and to educate others on the history, culture, and customs of the Chinese Ameri-

An assortment of Asian goods, from imported Chinese tea to packaged dried fish, line the store walls in Yin Wall City, Inc.

When I first stepped off the El

and laid eyes on ChinatownI was amazed.

The windows of Yin Wall City, Inc. are lined with posters and products to attract people walking around Chinatown.

14 nuAsian spring 2009

Photos by Jen T.

can community.” I continued to walk down Wentworth

and within minutes I felt as if I had entered another country. English had almost disappeared and replaced by a mixture of traditional and simplified Chinese charac-ters on the storefronts. The stores ranged from restaurants and teashops to banks and acupuncture clinics.

I had heard of a great teashop on Wentworth called Ten Ren Tea Company. As an avid tea drinker, I figured this would be a good place to start. Unfortunately, it was closed by the time I found it. But the Web site, tentea.com, offers a wide variety of Chinese teas. One can find Oolong tea, Pu-Erh tea, White tea, and much more. These teas, however, are not the typical Lipton teabags; they each have specific fla-vor, texture and shapes. With money still in my pocket and no tea in my hands, my photographer, freshman John Gray, and I continued the walk. We entered a small grocery store in the heart of Chinatown Square.

Completed in 1993, Chinatown Square is a two-level commercial center filled with shops and restaurants. On my first visit, there was not much activity, probably because most of the shops were closed. But on my second visit, the square was bustling with life. People were walking around admiring the stores, talking in both Can-tonese and Mandarin dialects and enjoying the brisk autumn night.

While we were walking around the square, I noticed a small store named “Yin Wall City Inc.” Inside there were 30-plus barrels filled with differ-ent kinds of ginseng. Ginseng is usu-ally sliced into thin pieces and used in tea or other overall health products. As I looked around, I spotted an array of foods not found in many American grocery stores. The prices ranged

from a mere $15 all the way up to $1000 per ounce.

Luckily, one woman working at the store spoke very good English. She explained that normally, the older the ginseng, the more expen-sive. “Most of the time, the products for sale in the store are used for food purposes,” she said.

Among the products were deer antlers, deer tails, shark fins, sea cucumbers, dried fish, giant mushrooms and even tea! In the corner of the store, a man and a woman sat at a small table talking and laughing over a teapot and a cup of tea. It was nice to see such an inviting atmo-sphere located within a local grocery store. After buying some sliced ginseng we said goodbye

and carried on with our cultural quest.

One aspect of Chinatown

that surprised me was the

influence of other types of cultures.

For example, in a candy story

we saw mostly Japanese candies. We bought

some dried fish, Pocky Sticks and

some gummy treats. At the store, I talked

with a student named Ashley Huang. She is

19, and a college student from Chicago. She has lived in Chinatown for two years and lives about a ten-minute drive from Chi-natown Square. Her favorite place to hang out in china town is Saint Alp’s Teahouse. Located on Archer Ave, this teahouse is a place where students come to hang out and work on homework.

After saying goodbye, we headed to a local movie shop. After chatting in Chi-nese, Mr. Zhao, the owner, was extremely friendly, and I’m sure that he enjoyed my attempt at Chinese. Originally from the northeast region of China, Mr. Zhao has lived in the states for 14 years. His video store has Chinese, Japanese, Korean and Taiwanese movies. Zhao stated that he sees a difference in the movies residents and non-residents rent. “Most Asian residents like the family movies, while non residents come here for the Kung Fu.”

I had no idea that such a rich culture was still

Dragons are sacred and are believed to have magical powers just like the number nine. Walk across the street from the Chinatown Gate to experience the

power of The Nine Dragon Wall. Modeled after the most sophisticated wall in BeiHai (North Sea) Park in Beijing, the Chinatown mural replicates the large dragons and over 500 smaller dragons painted in red, gold and blue signifying the Chinese focus on good fortune. The Nine Dragon Wall is one of the only three such replicas outside of China.

-- From www.chicagochinatown.org

Chinatown's Nine Dragon Wall

preserved in the modern age.

Photo by Peter Ng

15nuAsianspring 2009

Photos by Jen T.

The famous “Pocky” snack: Biscuit sticks coated with strawberry.

Alas, it was finally time to eat. After browsing the restaurants in the square, we headed to Ken Kee Restaurant. Chinatown is home to all different restaurants. A hun-gry traveler can find almost any type of southeastern or far eastern restaurants. According to Chicago-chinatown.com, there are around 40 restaurants along Wentworth and Cermak, though, after visiting, the number seems to be much higher than 40. Fortunately for me, I didn’t take the time to count them all. I was hungry and all of my attention was focused on ordering some tradi-tional Chinese food.

Ken Kee offers over 100 differ-ent entrees. Again, I did not take the time to count them all, but rest assured, there were more than 100. It was strangely difficult to pick just one dish from the large selection. Some of the highlights from the menu are water crest in garlic sauce, stir fried egg with yellow chives, Vermicelli with pickled veggies, and my personal favorite, sesame beef

chow mien. As our second trip came to an end,

we finally arrived at the Chinatown mural. The mural is an astonishing sight, made of 100,000 individually cut pieces of mosaic glass. It was creat-ed in the Tang Shan Art and Industry factory in 1993 and was cut into pieces before being sent to Chinatown for reassembly during completion of the square that year. The mural beautifully depicts the history of Chinese immi-grants in America. On the left, one can see ancient Chinese people working in the fields; in the middle there are people of different race holding hands in triumph; and on the right, Chinese people are working various modern day occupations.

The mural was a great spot to end my visit because it gave me an important incite as to how many chal-lenges Chinese Americans have had to overcome. As I walked away from the Chinatown Gate, I held my bag of goodies and admired the thick Chinese microcosm of culture that hides in the heart of a thriving American city.

Photo by Ashley Lau

Where to find the places Sam visited:

Ten Ren Tea Company2247 South Wentworth AveChicago, IL 60616(312) 842-1171

Yin Wall City, Inc.2347 South Wentworth AveChicago, IL 60616(312) 808-1122

Saint’s ALP Teahouse2131 S Archer AveChicago, IL 60616(312) 842-1886

Ken Kee Restaurant2129 S China PlaceChicago, IL 60616(312) 326-2088

CHI

NATO

WN

16 nuAsian spring 2009

A

17nuAsianspring 2009

western campus, JK Sweet is a casual dining restaurant

The faces of Café J.K. Sweet

On any given day you visit Café JK Sweet, the first thing you are sure to notice are the checkered tablecloths and a showcase of delectable desserts reminiscent of a ‘50s style

American diner. You can expect a lively woman behind the coun-ter to greet you with a warm “hello”. She is Heera Lee Shim, one-half of the duo that runs and maintains the café. The other half is a bespectacled and bearded fellow who is most likely bustling around in the kitchen – her husband, Jae-myung “Jae” Shim.

Shim and Lee took over the business last January, becom-ing the third group of owners in the lineage after John Klein, the eponymous owner who founded the café more than 20 years ago.

Located at 720 ½ Clark Street just steps away from the North-

by Iris Kim

that specializes in Korean and Japanese dishes prepared with premium ingredients handpicked by Shim himself, who travels to a local market every couple of days to ensure the fresh-ness of the food items. The most popular dish is, without a doubt, bibimbap – a savory combination of rice, sautéed

Photo by Ashley Lau

18 nuAsian spring 2009

vegetables, a choice of meat or tofu, and gochujang (a spicy, red pepper paste). Shims says the chicken teriyaki, donkatsu (fried pork cutlet), and galbi (barbecued beef ribs) are a big hit as well. Although most of his customers order the bibim-bap, Shim recommends seol-leong tang, a traditional Korean beef soup that he says is especially tasty during the winter months.

The café is open daily from 9:30 am to 12:30 am, or sometimes even an hour or two later. On top of that, the Shims are on the road for at least two hours every day, commuting back and forth between the café and their home in Buffalo Grove, a northwest suburb of Chicago. Shim says he and his wife run on only about three to four hours of sleep every night.

However, it is evident that in end, the reason they work so diligently is for the wellbeing of their children – Jane, a junior at Shim’s alma mater, the Univer-

sity of Michigan; Matthew, a high school sophomore; and Paul, a 3rd grader. Shim says the major reason why he and his wife moved to the states to run the café was to provide a better education for their kids. As much as the couple enjoys serving the customers, they regret not being able to spend more time with the kids. “For that, I am especially sorry,” Shim says.

At JK Sweet, Shim and his wife are ac-companied by just three other employees: one manager, a cashier, and an assistant cook. Shim appreciates the fact that between the five of them, the tasks, such as manning the cash register and preparing and serving the dishes, may be carried out efficiently. Additionally, this allows for a customer-oriented atmosphere in which Shim and Lee can not only serve the cus-tomers themselves but also concentrate on establishing close-knit relationships with their regular customers.

“The service is great, and the food is yummy,” says Deanna Mei, a Weinberg sophomore. “I’d never tried bibimbap before coming to college, but I was hooked after trying it for the first time at JK. I’m glad that there’s a place like JK so close to campus - it’s really convenient to just stop by and grab a quick and satisfying meal.”

Shim says that the best part about his job is being able to meet and interact with customers in a college-town setting. “I really like that I can meet young people on a daily basis. I forget my age sometimes,” he reveals.

On the whole, Shim says he is quite fond of Evanston as a gentle and well-mannered community. Lee, in particular, encountered somewhat of a language barrier when she came to the states for the first time in 2007 with her husband to help him manage the café.

“My wife is very brave,” Shim says, with a chuckle. “Most of the time, she doesn’t care what she is saying as long as she can get the general point across. I am thankful because the customers are understanding and treat her well.”

Shim and his wife have always led a nomadic lifestyle. Born and raised in Seoul, South Korea, Shim graduated from college in Korea, earning a degree in biol-ogy. The Shims then came to the states and settled in Ann Arbor, Michigan for graduate and postgraduate study. The two then went back to Korea for a short time period before spending around 10 years in Southeast Asia, living in places such as Thailand, Singapore, and Indonesia. The Shims have lived in the Chicago area for just under two years, but they already envision themselves relocating to another place in the future.

“My wife and I love to travel, especially to places with beautiful nature. After the kids graduate from college, we will prob-ably leave Evanston. Maybe somewhere tropical? Or Africa? Who knows?” says Shim. Husband-and-wife duo Heera Lee, left, and Jae-myung Shim are both proud café owners and proud parents.

Photos by Ashley Lau

A

n high school, Derrick Wu said teachers expected a lot from him, not because of his academic potential, but because of his race. “Teachers used to come up to me and say they had other Asian students who did well,” the Northwestern freshman said. “It’s hard for any Asian to live up to those expectations.” As the only Asian at his school in Indiana, Wu said he was often pegged as smart, high-achieving and quiet—stereotypes that many Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders often face, but hardly question. “The stereotype could be much worse,” Wu said, who admits he has some nerdy qualities. The commonly held belief that Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders are better off academically, financially and professionally compared to other groups can trace its origins to a decade defined by another minority’s struggle for equality—the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. In response to the protests and turmoil among the African Ameri-can community in the 1960s, many white Americans turned to the Asian community as a solution. And so the “model minority myth” was born.

The Model Minority Myth

by Nathalie Tadena

19nuAsianspring 2009

I

Photo courtesy of www.fiddlemaestro.

Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders were elevated as a “model minority,” a term first used in 1966, to illustrate the capability of one racial minority to achieve the American Dream and to fault the African American community for their failure to do the same. “It was a contrast to what they were saying about blacks at the time, a way to show that welfare is not the solution to solving the problems for African Americans,” said Robert Teranishi, an associate professor higher education at New York University. “Asians were used to demonstrate that with hard work and diligence, minority groups can be successful.” Teranishi co-led a study conducted by the College Board and the National Commission on Asian American and Pacific Islander Research in Education titled, “Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders—Facts, Not Fiction: Setting the Record Straight.” The report, published in June, challenged popular stereotypes and examined the detrimental effects on Asian American students. “There are a lot of Asians who aspire to the American dream, but that’s true of all immigrants,” Teranishi said. “Somehow it becomes more of an Asian story as opposed to an immigrant story.”Many of these misconceptions are a result of misleading data that overlooks differences among ethnic groups, Teranishi said. According to the 2005 American community survey, more than 4 percent of respondents identified themselves as Asian or Pacific Islander. However the term “Asian-American” en-compasses at least 20 different ethnicities and nationalities, ranging from Indian to Chinese to Vietnamese. Teranishi’s study found significant economic and educa-tional differences among Asian and Pacific Islander ethnic groups. Although more than 44 percent of Asian Americans earned a bachelor’s degree of higher, compared to only 24.4 percent of the U.S. population, southeast Asian groups were the least likely to graduate. Less than 20 percent of Vietnamese and less than 10 percent of Cambodians, Laotians and Hmong received a degree. Of the Pacific Islander groups surveyed, Native Hawaiians had the highest likelihood of graduating with a degree, with only 15.8 percent. Asian and Pacific Islanders also showed comparable poverty levels to the national average, with 12.6 % of Asian Americans and 17.7% of Pacific Islanders falling below the poverty line. About 12.4% of the overall U.S. population lives below the poverty line.

Photo courtesy of www.flickr.com

20 nuAsian spring 2009

“It’s hard to challenge a positive stereotype, who doesn’t want to be successful?” Teranishi said. However these “positive stereotypes” continue to hurt Asians, said Jinah Kim, a professor of Asian American studies at Northwestern. “The model minority myth doesn’t really describe who Asian Americans are,” Kim said. “It describes how people in power want Asian Americans to be.” Asian American groups represent a diverse range of socio-economic classes, however, under the model minority myth, all Asians are lumped together as the “good people of color,” she said. While Asian Americans may not have been the ones to cre-ate the concept of the model minority, many young Asians feel pressured to internalized the model minority’s stereotypes.

The Asian Population at Northwestern Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders make up the largest racial minority group in NU’s undergraduate student body. Approximately 17.2% of the students entering NU in 2006 identified themselves as Asian. Sophomore Lydia Hsu said stereotypes differ from place to place depending on the prominence or presence of Asians in the area, noting that there were few Asians where she grew up in upstate New York. “People expect you to get straight As and be the smartest one in class, and when you’re not they’re shocked because as an Asian American, you’re held to a higher standard,” Hsu said. “It’s really annoying because the culture pressures us to be better, we’re not inherently better.” Coming to NU, the sophomore English major said she found that many students are trapped in an “Asian bubble.” “If people associate you with a certain group of Asians or Indians or racial group, they’re less intimidated to friend you because they’re intimidated by your group.” Diana Chen, also a sophomore, said many people are sur-prised when she tells them her major of study. “There are a lot of stereotypes like you’re supposed to be hard working, play an instrument, be someone’s who’s really good at math and science,” she said. “A lot of people don’t guess that I’m studying music and political science, they always assume I’m premed or an econ major.” The Model Minority Myth is something many Asian-Amer-ican college students grapple with, however, the most difficult stereotypes to dispel are the positive ones, Kim said.

21nuAsianspring 2009

“This places a burden on the Asian American individual and family,” she said. “It makes achievement seem natural so if you don’t achieve that must be because you’re not a good Asian.” Because the model minority myth tends to emphasize achievement in the areas of scienceand math, some college students may be discouraged to pursue studies in the arts. “The model minority just cannot recognize the plurality of Asian American desires and experiences, it might even limit the students’ ideas of what they become,” she said. There are two ways that young Asian Americans in college tend to respond to the pressure placed on them to do well, said Shuji Otsuka, a PhD candidate at Northwestern and a graduate instructor in the Asian American Studies department. “One way that they would respond is to place very high expectations on themselves, work hard in high school, get into the best college, in college get very good grades and when they do not meet those high goals and high expectations, they beat themselves on the head,” he said. The failure to meet expectations can even have psychological repercussions. Suicide is the second leading cause of death for Asian American women between the ages of 15 and 24, marking the highest suicide rate among women of any race in this age group. In contrast, some youth attempt to reject the modelminority myth all together. “There is a counter-tendency to not work hard and not get good grades,” Otsuka said. “Some tend to reject the image that model minorities are rather nerdy and out of touch, they want to be cool in college and high school.”

Can the Myth be Debunked? As long as Asians are distinguished as foreigners rather than Americans, experts say the model minority myth will continue to persist. Northwestern, like many of its peer institutions, offers classes in Asian American studies, however, Kim said there is not enough interest or resources to educate the entire campus about the Asian American experience. Greater appreciation and understanding of what it means to be Asian American can be fostered through increased support for teaching Asian American literature and history at high school and elementary school, Kim said. Because Asian Americans are expected to be educationally successful, many schools do not reach out to Asian students for extra support, often leading to higher degrees of stress and anxiety as well as lower satisfaction in college, Teranishi said. One major issue is the lack of visibility of Asian American leaders in educational and political institutions. Asian Americans make up approximately 1.5% of teachers nationally and only .5% of principals in K-12 schools. “Asian Americans just don’t see themselves in schools, they don’t see themselves or their experiences reflected in the curriculum or part of American history,” Teranishi said. Because many Asian Americans do not actively seek out educational support, Teranishi recommends that student services at educational institutions should be better educated about the unique issues the Asian community and different subgroups within that community may face. “People need to understand that Asians are not a homogenous groups,” Teranishi said. “There are a lot of different communities of Asians in America and a wide range of experiences and challenges that exist within the population. A college in Minnesota might be dealing with a large Mong population, in Louisiana there is a large Vietnamese population, in New Jersey there are a lot of Filipinos. Institutions need to think about who it is they’re working with when it comes to the Asian population.” Photo courtesy of www.flickr.com

A

I had heard of the glass ceiling against women before my intern-ship this past summer, but little did I realize there existed a ceiling just as tough against Asian Americans in the workplace.

This barrier is not necessarily intentional, but rather a result of the clash between cultural differences.

The 2002 U.S. Census reported that 44 percent of Asian Ameri-

above the 27 percent average of the total population, yet Asian Americans comprise a mere 1 percent of corporate board member-ship. Why the discrepancy?

Americans have built a capitalist society that prides individu-alism and freedom. As a result, many corporations have cultures that emphasize competition, aggressiveness, and initiative. Asian culture, on the other hand, tends to be more communalistic in na-

priority of duty and harmonic peace over personal rights. As a re-sult, many Asian Americans forgo personal gain in order to avoid

I noticed this in my internship at Lehman Brothers this past summer. I worked closely with a Korean American analyst who was extremely traditional in Asian values and behavior. Her boss was frequently condescending and demanding, and despite being very frustrated with the degrading treatment, she never spoke up or talked back. Ironically, her manager’s favorite analyst was instead someone who often made sarcastic comebacks. The Korean Amer-ican created better spreadsheets and presentations than many of her coworkers yet she was handed the most menial projects be-cause she failed to speak up about her own strengths and was too timid to ask for the best projects. She was not popular among her coworkers and was not promoted as she stuck her nose constantly in her work and failed to network and socialize enough with those

22nuAsianspring 2009

by Kaixi Ouyang

around her. Many Asian Americans are taught by their parent that success

is dictated by hard work and academic success, a reason why Asian Americans have been labeled a “model minority” group. Unfortu-nately, advancing in the workplace is completely different from do-ing well in school. People are not promoted on the basis of grades or test scores. Simply producing quality products and results is not enough. Many other factors come into play: how well you network, how well you get along with your manager and coworkers, how as-sertive you are, how well you can demonstrate your performance to those who decide your promotion, etc. In fact, often times these subjectively evaluated “soft” characteristics are more important than the technical work you produce.

So how does an Asian American expect to succeed in the cor-porate rat race? You do not need to deny your Asian heritage and act “white”. You should not let your performance slip. However, you do need to be able to communicate and build camaraderie with

dominant culture at your company. Good relationships with your

than some technical skill or knowledge you possess that can be eas-ily replaced by another employee or a machine. You are promoted by people, not books or computers.

You can also use Asian American traits like humility, modesty, and respect for the community to your advantage. These charac-teristics put people at ease and create collaboration. Just don’t be so humble and modest that you never voice your best qualities and let others take advantage of you. Don’t allow yourself to get stuck with all the grunt work like Harold from Harold and Kumar go to

sure other people know it too.

InÊmyÊwords

Photo courtesy of www.businessweek.comArtwork by Pongkarn Chakthranont

Asian Americans in the workplace

A

22 nuAsian spring 2009

Asian AmericanWhat does it mean to be

in the21st Century?

More than ever, Asian Americans compose a diverse group of individuals. Whether of mixed ethnicities or full Asian descent, whether born overseas or born in America, whether a third-generation or first-generation American, Asian Americans in the 21st century are redefining what it means to be “Asian American.” The term “Asian American” no longer reflects just one type of person or one stereotype, but rather a number of diverse people living in America.

23nuAsianspring 2009

Being an Asian-American is self-declared. If you believe yourself to be influenced by both, why not be Asian-American instead of one or the other? Self-categorization of this term is its unique and characterizing factor.

—Devon Weiss (WCAS ‘11)

To be Asian-American is to be an Asian born in America who is proud of not only his/her Ameri-can heritage but his/her inner Asian roots as well.

—Harry Li (WCAS ‘11)

Someone who is racially Asian but culturally Amer-ican (with sprinkles of an Asian heritage on top).

—Irene Liang (WCAS ‘11)I am not an Asian American, but I believe that the common struggles and differences be-tween the heritage and culture has created a united bond that brings the Asian American community closer as a whole.

—Jon Cook (McCormick ‘12)

What does it mean to be an Asian American? As someone who grew up in both Taiwan and the US, being an Asian American means that my values are influenced by both Asian and American mindsets. Also, I get to call two places home which is double the excitement!

—Sharon Kuo (WCAS ‘11)

File photos courtesy of www.imdb.com and the AP