November 2012 CONSERVATION Africa - lions4lions.org · volume 1 - issue 6 november 2012...

-

Upload

dangnguyet -

Category

Documents

-

view

216 -

download

0

Transcript of November 2012 CONSERVATION Africa - lions4lions.org · volume 1 - issue 6 november 2012...

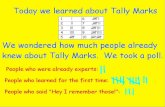

Volume 1 - Issue 6 November 2012

CONSERVATIONAfricaSAVING AFRICA’S SMALL CATS

BREEDING LOWVELD CHEETAHS

AFRICA’S LIONS: THE END OF THE LINE? LION BONE TRADE EXPOSED

KEEPING WILDLIFE IN PLETT

THE AFRICAN CAT ISSUE

THE END OF THE LINEfor the

LION KING?Africa’s lions are facing a new threat from Asia - the lion bone trade. And it appears that South Africa’s captive lion breeding industry may be supplying lion bones and could ultimately fuel demand. We investigate the newest wildlife commodity - one which could compromise Africa’s wild lion populations forever.Africa’s lions are in trouble. The species has declined tremendously over the past 45 - 50 years on the continent with numbers dropping from almost half a million to between an estimated 20 000 - 30 000 individuals in sub-Saharan Africa. According to UK-based NGO Panthera, lions have vanished from 80% of their historic range and there are now a mere seven African countries believed to hold more than 1 000 lions. A 2005 study on the status and distribution of African lions estimated that there were between 3 800 and 4 200 lions in South Africa, if fenced reserves were factored in.

In areas where wildlife is not fenced off from the local, rural populace, these golden predators face a tenuous existence. Many such people walk in fear of the lion, which is subject to persecution because of the threat it poses to personal safety and livelihoods. As human beings encroach on wildlife habitats, prey availability for creatures such as lions is reduced and the animals of necessity turn to other forms of prey such as domestic livestock, which fuels existing human-wildlife conflict. In Kenya, lions and other large predators are killed because of their tendency to prey on sheep, goats and cattle - often using deadly poisons, gin traps and other inhumane methods that affect other, non-target species as well. Panthera estimates that, at current rates of loss (100 lions/year), Kenya’s lions will no longer exist in that country by 2030.

But another, new threat faces Africa’s lions. As with the rhino, this is fuelled by the burgeoning Asian demand for wildlife products - in this case, lion bones. Alarmingly, South Africa appears to be at the centre of this new trade. CITES records and statistics released in 2011 by the South African Department of Water & Environmental Affairs indicate

that trade in lion bones began in 2009 when lion carcasses were first recorded as having been exported to Laos. According to a March 2011 blog by the Campaign Against Canned Hunting (CACH), 92 lion carcasses were exported to Laos in 2009. This jumped to 235 carcasses in 2010, representing an increase of 150%. CACH contends that “this constitutes a significant injection into the Asian trade in wild cat parts and derivatives that... is likely to increase demand for lion parts - not just those from captive bred sources in South Africa but from all sources throughout the rest of Africa too. Indeed the leap is strongly indicative evidence that this perceived/potential increase in demand is already well under way.”

Karen Trendler, well-known wildlife rehabilitation and animal welfare specialist, tells me: “In 2010, the NGO Alliance grouping (which included the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals and the Endangered Wildlife Trust) not only offered to assist the Department of Environmental Affairs in addressing the canned lion issues but also warned against the possibility and risks of the lion bone trade becoming established. Sadly the warnings were ignored and this lion bone trade has now established itself.”

So what is the link between the lion bone trade and captive bred lion hunting in South Africa? To explain this, we need to clarify certain developments in the country’s trophy hunting and wildlife industries. South Africa has a rather unusual situation in that a large chunk of its wildlife is in private hands, sequestered behind fences on privately owned reserves or game farms. The situation arose ostensibly for conservation reasons, to ensure the protection of the country’s wildlife. Private reserve and game farm owners were deemed to have more

Text: © Bronwyn Howard | Pictures: © Jock Tame

resources and be better equipped to protect wildlife, as well as being able to generate income from ecotourism and trophy hunting. This situation also led to large tracts of land being converted from agriculture to more natural habitats.

Then, in 1997, the Cook Report exploded the “conservation” myth when it raised the curtain on diabolical practices in at least some segments of the trophy hunting industry. According to the report, certain lion breeders were raising lions purely for sport hunting. While this in itself is not necessarily a problem, the issue was that these lions were being bred, maintained and kept in small enclosures until being hunted (this could be between five and seven years for a trophy male). Karen Trendler advises that such lions may be placed into these completely unnatural situations from a very young age. The NGO Alliance’s concerns were not only about the manner of death but also the conditions under which these predators were being bred, spending years in poor environments before being hunted by foreigners wanting a guaranteed, low-risk “kill” and a lion trophy to take home. The concept of fair chase was naturally absent from such hunts, as the lions were unable to escape. A report prepared by Richard Hargreaves, UK Director of CACH, states that in this form of hunting, known as “canned” hunting, lions are often deliberately imprinted towards humans (so they may even approach the hunter, thinking that he is bringing food) or even drugged to make them easier targets. Following the documentary’s release in South Africa, there was much hue and cry.

Louise Joubert, who runs a wildlife sanctuary and rehabilitation centre in Limpopo Province, explains what happened next. “The South African government at the time, represented by the Minister of Environmental Affairs, vowed to stop it - but they never did. A media statement was issued saying they would implement a moratorium on canned lion hunting but the trouble was that they left it up to the provincial MECs to stop issuing lion hunting permits, so it effectively became a voluntary thing. In fact, only Mpumalanga and KwaZulu-Natal provinces actually did this. In three provinces - the Free State, North West and Limpopo - the practice of so-called canned lion hunting was allowed to continue.

“At the time, there was no legislation governing captive lion breeding. There was only a permit system in place,

South Africa has a rather strange situation in that most wildlife is in private hands, on private reserves and game farms. This was deemed good for conservation - until the Cook Report revealed the existence of “canned” lion hunting operations in South Africa in 1997.

whereby lion owners needed to obtain a permit to hold and breed lions in captivity. However, a situation arose where lion owners started holding lions without permits. We also have a very strange system in South Africa where the provincial authority can override any decision made by central government; legislation is recommended to provinces but they can implement it or not as they see fit. It was this state of affairs that allowed the canned lion hunting industry to develop. By the time the Cook Report was aired, lion owners had invested millions of rands in this industry. Nevertheless, it was very apparent that government had to put new laws in place.

“What the government then did was to hold public participation meetings with the South African public and the hunting industry. Issues discussed included whether canned hunting should be allowed to continue in South Africa and how the industry should be regulated. A panel was established to consider these issues. Marcelle French, who was then with the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (NSPCA) was part of the panel. According to her - and this was never made public - the panel recommended to government that the canned hunting industry should be shut down. The problem, however, was that permits had already been issued and breeders, as mentioned, had spent millions developing these operations. The then Minister of Environmental Affairs, Martinus van Schalkwyk, was opposed to the industry, referring to it as a ‘cancer of society’. Lion breeders began bringing legal cases against the government. The fact remains that the industry should have been phased out if public opinion was against

this form of hunting. But government actually did not follow through and the whole process effectively became a farce. Government eventually met with all interested parties and said that they would make a unilateral decision.” Karen Trendler adds that it was not only the public’s opinion that had to be taken into account; many local and international hunting organizations were and are also opposed to this practice.

It took the South African government a number of years to enact new laws regulating the hunting and wildlife industries. In 2004, the National Environmental Management: Biodiversity Act (Act 10 of 2004) (NEMBA) was passed. Part of the Act included the Threatened Or Protected Species (TOPS) Regulations, which were passed in 2007 but were only enacted from February 2008. Hunting norms and standards were also gazetted as part of NEMBA in 2011 and related primarily to the use of rifles and bows for hunting, as well as setting standards for falconry and game bird hunting. The TOPS regulations govern the keeping of threatened species in captivity as well as the hunting thereof. There were high hopes regarding the content of the regulations, as it was hoped that this would effectively outlaw the canned hunting industry. According to Richard Hargreaves, the regulations did not apply to lions specifically (although hunting was prohibited in the case of animals such as Nile crocodiles and rhino) so they were, he and others believed, not a deterrent.

The regulations were in dispute from the minute they were enacted.

Caught in the middle - Captive lions became the subject of legal battles when the South African government brought out its Threatened Or Protected Species (TOPS) regulations, some of which were hotly disputed by the South African Predator Breeders Association.

Louise Joubert explains: “The law effectively said that game farmers and reserve owners could continue to breed lions but the regulations do not specify things such as the size of enclosures and other issues pertaining to animal husbandry and welfare. That was left to provincial authorities to decide. One of the things that ultimately became an issue was that one of the regulations specified that a lion bred in captivity had to live in the wild in a natural area measuring at least 2 000 hectares and be self-sustaining - in other words, hunt for itself, breed and survive - for a minimum period of 24 months before being hunted.”

Unsurprisingly, the South African Predator Breeders Association had various issues with the new regulations, including this requirement, and they took the government to court. Rynette Coetzee, of the Endangered Wildlife Trust’s (EWT) Law & Policy Programme, explains: “The Predator Breeders Association opposed the 24 month period when lions had to be released into a natural area prior to being hunted, as it was not based on any scientific evidence whatsoever.” Karen Trendler adds, “They also opposed the 24 month period because it impacted on the profitability of the hunt for them; it costs money, land and time to have a lion free ranging for that long.” The upshot of all this was that the South African Predator Breeders Association took the matter first to the High Court, where they lost and then to the Appeal Court, where they won. The judge ruled that the Minister of Environmental Affairs had not taken a “rational decision” when he determined that captive bred lions had to fend for themselves in an extensive wildlife system for 24 months before they could be hunted. He added that the “period of 24 months bore no rational connection to any legislative purpose of the Act” and, further, that the “24 month delay was arbitrary and unsupported by scientific evidence.” While the South African Predator Breeders Association and local media made much of this, not all the Association’s objections to the TOPS regulations were ruled upon and the other regulations were upheld.

However, as CACH pointed out in a blog written shortly after the appeal case was finalized: “We maintained that [the period of 24 months] was nothing more than pretence; namely, ‘if we can pretend that a lion is wild then we can pretend that canned hunting has been banned.’ The Minister’s aim was to use this public relations gimmick to deflect public anger and at the same time allow canned lion hunting to continue behind the cloak of regulation... The 24 month wilding rule was a publicity stunt which had no place in conservation and that is exactly what underlies the Supreme Court’s decision.” Karen Trendler agrees and says that the re-wilding period was nothing more than a means to sanction canned lion hunting. “One of the reasons why the Predator Breeders won the final case was not because it was believed that canned hunting was okay but because of the arbitrary and unsupported release and re-wilding period - in spite of the fact that various experts had made submissions on the requirements for re-wilding.”

Mr Gareth Morgan, shadow Minister for Environmental Affairs for the Democratic Alliance, asked the Minister of Water and Environmental Affairs whether she would be taking any steps to prohibit what he termed “canned” lion hunting. She replied that she was unable to do so, as the Supreme Court had ruled that the Minister of Water and Environmental Affairs does not have a legal mandate in terms of NEMBA to regulate canned lion hunting. However, she said that she had instructed the Department’s biodiversity and conservation officials to engage with officials from the Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (DAFF) around the issue of whether “canned” lion hunting could be regulated in terms of their legislation. As feared by some conservationists, this would place captive bred lions squarely within the realm of agriculture and not conservation. Karen Trendler comments: “Captive lions are not the only species that have been caught in the conflict between the Departments of Water & Environmental Affairs and Agriculture; captive elephant is another species that has fallen through this crack.”

Lions are protected by law - but only as far as hunting is concerned. Only provincial legislation stipulates issues such as enclosure sizes, fencing types and how soon after re-wilding a captive bred lion may be hunted. Animal husbandry issues fall under the Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (DAFF), which does not do inspections, so animal welfare becomes an ethical and moral issue rather than one governed by law.

However, Rynette Coetzee says, “The rest of the TOPS regulations still stand. Lion owners need permits to possess, breed, trade in, convey and hunt lions in captivity. Hunters also need permits to hunt both captive bred and wild lions under any circumstances. Regulation 26 sets out prohibited hunting methods, for example, which also apply to both captive bred and wild lions.” Regulation 26 states that listed threatened or protected species (including lions, which are listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red Data List) may not be hunted by means of poison, traps (except in certain defined circumstances), snares, dogs, darting (except in certain defined circumstances), using an automatic weapon, a .22 or smaller calibre weapon, shotguns (except for birds) and airguns. The Regulation does, however, allow for the use of bait to lure lions, leopards and hyenas, as long as the bait is dead. The use of sound, smell or any other induced luring methods are prohibited. The animal may also not be hunted using flood or spotlights, motorized vehicles or aircraft. Hunting is also prohibited if the animal is under the influence of any tranquillizing, narcotic, immobilizing or similar agent; or if trapped against a fence in a small enclosure where the animal does not have any chance of evading the hunter.

Various hunting associations, including the Professional Hunters Association of South Africa (PHASA) and the South African Hunters and Game Conservation Association are quick to say that they are against canned lion hunting and do not condone it under any circumstances. “Lion hunting in the context of canned hunting is very illegal,” Dr Herman Els, Manager of the South African Hunters and Game Conservation Association, tells me. He adds, “The existing regulations need to be improved because the current status quo creates a situation where illegal activities can continue without being stopped. People are continuing to get away with these things.” However, both organizations state that captive bred lion hunting is another matter entirely, as it is both legal and legislated. Bearing in mind that the majority of these captive lions are bred specifically to be hunted and kept in enclosures until being released for a specified period to comply with provincial legislation, this is something of a fine line.

Herman explains: “Provincial regulations governing lion hunting are very clear regarding how hunting operations should conduct themselves. Lion ranching is similar to cattle ranching. Cats and lions are placed in small enclosures for breeding purposes, the size of which is also regulated at provincial level, and then released into larger areas before they are hunted. The time the animal needs to fend for itself varies; in North West, for instance, the animal can be hunted 96 hours after release, whereas, in the Free State, you have to wait one month before you can hunt the animal - it used to be three months. The differences in regulations between provinces are problematic. This

means that outfitters could move lions across provincial boundaries so that the animals can be hunted sooner.”

Karen Trendler adds, “Re-wilding the lion for 96 hours may be far crueller than just shooting the animal in its original cage; for 96 hours it is in a completely strange and unfamiliar environment and, in this state of stress, it is then ‘stalked’ and hunted! As regards the Free State regulations, there is no way that a captive bred lion can be re-wilded in one month.” Rynette Coetzee tells me, “Captive bred lions are not used for hunting in the Northern and Western Cape and no predators may be hunted in Gauteng.”

We ask Herman what size area the lions are moved into and whether they are released in groups, as lions are the most social of the cats. He says, “We place lions in family groups; they must be placed in camps together. The hunting of ranged lions is not easily managed as they are generally released into an area of between 1 000 - 1 500 ha, about the size of the average game farm. When they are released into the natural area, they are not in their comfort zone and may initially be very aggressive and dangerous.” Rynette Coetzee disagrees. “When these lions are released into the nature area, they are often very nervous and confused and this makes them easy to hunt, as they are still vulnerable and unsure of themselves and their safety - so it is still not a fair hunt. It also takes at least 48 hours for the tranquillizing dart - used to enable the lion to be moved - to wear off fully; the period of 96 hours between release and hunting recommended in North West Province probably gives only just enough time for the tranquillizers to wear off. I have seen footage where a lion still groggy from tranquillization was being hunted by five people. In the Free State, it is compulsory that an official is present to monitor the hunt; this is also a requirement in Limpopo and North West Provinces but there the hunt is only actually monitored in practice if an official happens to be available at the time when the hunt is being conducted.”

The trouble is that captive bred lions are no longer “wild”- as far as that definition holds in South Africa, where most lions are in fenced reserves, whether public or private. Kelly Marnewick, Manager of the EWT’s Carnivore Programme, explains: “Firstly, lions breed very well in captivity. These captive lions, however, are not included in the IUCN Red Data Book as they are not regarded as part of the wild population.” Rynette Coetzee adds, “Lions are listed under CITES Appendix II.” CITES excludes domesticated Felidae species but all lions, whether wild or bred in captivity, still fall under Appendix II of CITES for any activities relating to trade and sport hunting.

Kelly goes on to tell me, “There are around 1 600 - 1 700 lions in the

Kruger National Park with the balance being in various smaller parks such as Pilanesberg National Park and private reserves. Most lions are in fenced reserves but there is a small, wild population near the confluence of the Shashe and Limpopo Rivers. They move between South Africa and Zimbabwe - where they are persecuted and hunted. The number of captive lions is increasing. In 2009, there were over 3 600 lions in 167 facilities across the country, most of which were in North West Province, Limpopo and the Free State. I don’t have more recent figures but there are definitely more facilities now than there were in 2009. There are a number of facilities in the Lowveld, for instance, which never used to have any. As far as the captive bred lion hunting industry is concerned, this is actually a very small part of the hunting industry overall and it’s very much a case of the tail wagging the dog. Unfortunately, people are making a lot of money out of breeding lions and it’s tainting the whole hunting and wildlife industry. There is no doubt that captive lion breeding is having a significant impact, despite the relatively small number of people involved.”

Herman Els says, “We do not have exact numbers but I can tell you that the number of facilities now breeding lions is prolific.” In an e-mail, PHASA commented that it is a voluntary, non-statutory organization for professional hunters and hunting outfitters, representing the South African professional hunting industry. Statistics regarding registered hunting outfitters who market captive bred lion hunting are not being submitted to their organization. Karen Trendler says she believes that the number of such operations has escalated since the court ruling.

The period when the lion is in captivity appears to have given rise to several questions, especially as regards animal welfare. “After 14 days, the cubs are taken from their mother,” Louise Joubert informs us. “This ensures that the mother will soon breed again.” Richard Hargreaves enlarges on this, quoting Paul Hart of the Drakenstein Lion Park in the Western Cape, a facility that is in part a refuge for animals that have fallen victim to the captive bred lion industry. He says that the practice of removing cubs from the mother fairly early on ensures that the lioness produces cubs every six months as opposed to every two years or so, as she would in the wild - a fact that has enormous physiological and psychological implications for the hapless lioness. Louise says,

The Kruger National Park is home to some 1 600 - 1 700 of South Africa’s lions with the balance being spread over smaller parks such as Pilanesberg National Park and private reserves.

“The mother becomes a sausage machine, just producing cubs. This leads to the proliferation of inferior lions due to genetic issues, as well as vitamin deficiencies, and impacts negatively on the general health of the mother.”

What happens to the cubs after they are taken from the mother? “They must be hand-raised,” Louise says. “This task is often done by volunteers, who come to Africa believing that they are going to help wildlife.” She recounts the story of an Australian volunteer, who came to South Africa to do just this - and then discovered what was really going on. “She phoned me in tears,” Louise recalls, “and asked me if I could buy the cubs and take them away from the facility. I told her that it wouldn’t help if I bought them because these are just two of hundreds of cubs affected by this industry. Eventually, we agreed that if she bought them, our sanctuary would take them in, which we did.”

Karen Trendler confirms, “Cubs are often removed from the mother as early as three days after birth, as it’s easier to get them eating when their eyes are still closed. The hand rearing circumstances are also far from ideal and there is a high incidence of nutritional deficiencies and so on. Cubs are also used for tourism ‘pay and play’ activities; tiny, exhausted cubs are picked up, prodded and hauled around repeatedly for photographs and for children to play with.”

Louise tells us about the future of some of these animals. “Cubs are also sold to other captive breeding operations and used in petting zoos. In one evening alone, I found 48 lion cubs for sale on the Internet. There were also cheetah, serval, gennets and caracal. Hand-reared, captive bred lion cubs are often used in walk-with-lion tourist operations, where the lions may be drugged so they don’t hurt people.”

Paul Hart also says: “Cubs and immature lions in petting zoos may be handled up to 500 times a day. The cubs often live in appalling conditions when not in the public eye... The majority of lion breeders operate closed facilities [that are not open to the public], where they can basically do whatever they want with little or no consideration for animal welfare criteria. There are horrific stories of lions literally starving because breeders want to make the maximum profits and the animals are being fed inappropriate food such as cat pellets. Producing a good-looking lion does not require much by way of animal enrichment and suitable housing.”

Rynette Coetzee says, “While actual hunting is legislated, the animal welfare situation is not part of conservation legislation although provincial authorities now have policy documents setting out things such as the size of enclosures and the type of fencing that may be used. The Animals Protection Act 71 of 1962 applies but is currently enforced by an NGO - the NSPCA. The Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (DAFF), who is supposed to enforce all legislation pertaining to animal welfare, does not employ inspectors to do so. As a result conservation authorities will issue permits for the keeping of animals in ex situ (captive) situations, without giving a thought to the welfare issues involved. The treatment of the animals while in captivity therefore becomes an ethical or moral issue.” Karen Trendler adds that provincial authorities also believe that animal welfare is not their responsibility.

The worst part of it is that these captive bred lions can never be released back into the wild, although the public visiting petting zoos or taking part in walking-with-lion experiences are often told that they will be. Kelly Marnewick says, “Quite apart from anything else, South Africa is not short of lions but lacks sufficient wild spaces for them. The Kruger National Park cannot take in any

Lion cubs are the innocent victims of the captive bred lion hunting industry. They are taken from their mothers at a very early age and hand-reared to enter petting zoos, where they may be drugged and petted up to 500 times a day. Some are sold on the Internet. They often have insufficient food or nutrients and little is done by way of animal enrichment.

more lions and private reserves also have all the lions they want.”

A paper entitled Walking with lions: why there is no role for captive-origin lions in species restoration sheds further light on the matter. Since 1991, well-monitored efforts to restore lions to areas of the species’ former range have been undertaken in South Africa and Namibia. In all cases, wild lions were used and population re-establishment using wild lions has been extremely successful. Translocation does, however, rely on suitable wild source populations. Restoration efforts are generally more successful when wild animals are used as opposed to captive bred animals.

This is especially true for large carnivores with complex social dynamics such as lions, where captives are poorly equipped for survival compared to their wild counterparts. The impoverished setting of the captive environment may lead to maladaptive behaviour such as males killing adult females, high cub mortality as a result of failure to thrive, or being kidnapped and killed by a pride female. These aberrant behaviours are unknown among cohesive social groups of wild founders in South African translocation projects and would set back such projects. The founding population should also ideally be closely genetically related to the original native stock and show similar ecological characteristics to the original sub-population. Captive bred lions may lack important local adaptations, while hand-raised animals would have been selected for their tolerance of human contact rather than any natural selective process. The potential introduction of pathogens by captive animals could also be catastrophic for wild populations. Captive bred carnivores are exposed to numerous unnatural pathogens from close contact with both other captive species and humans but can only be screened for a limited number of well-known diseases.

Part of the problem is that the hunting industry in South Africa is a fairly big one worth a lot of money. “The hunting industry and all its derivatives is valued at R8 billion a year,” Herman Els says. Direct revenue from local hunting is around R3 100 million a year, whereas

foreign hunters bring in R1 200 million annually. Peter Warren, well-known breeder of rare sable antelope, who also offers hunting of captive bred lions on his property in the Limpopo Province, says to journalist Louis Theroux in the 2008 documentary, Louis Theroux’s African Hunting Holiday, after showing Theroux a large enclosure where he keeps lions: “This whole farm was paid for by Americans; hunting brings in more money than cattle [farming]. There is about R120 000 just walking around in here. All these lions will be hunted, we breed them for hunting.” Asked by Theroux if he loves his lions, Peter Warren scoffs, “There is no love when it comes to lions. They are just a plain commodity. Hunting is in any case an artificial experience, the same as bungi jumping. It would be like me going overseas to hunt a bear. Canned hunting is cheaper and less risky. The animals are also in better condition than in the wild; they are not scarred. Hunting is a sport even if the animals are being bred for hunting. In Africa, everything is chopped down and eaten. This is a way of making money from what is here. It doesn’t hurt me to hunt; the animals will go extinct if they don’t make money. If it were not for hunting, there would be no species left in Africa.”

There is an impression among the hunting fraternity that captive bred lion hunting is actually of benefit to conservation as it takes the pressure off wild lions. Besides the fact that captive bred lions can never be released back into the wild, for the reasons stated previously, Karen Trendler says, “Research indicates that the canned lion market does nothing to protect wild lions; in fact, the captive breeding of lions has created a completely new market. The hunters who are prepared to pay large sums of money and spend time on a proper hunt with fair chase and no guarantee are not the same people who take part in bargain canned hunts. There is a lot of disagreement on this issue. Our research also indicated that there is some division among hunting organizations as to the impact of this on wild populations. But certainly the captive population does not provide or contribute to global lion populations or lion conservation. There is lot of in-breeding and back-breeding in captive populations, which produces genetically compromised animals.”

In fact, captive lion hunting may be compromising the species survival in the wild. Richard Hargreaves states that the only truly free-ranging adult male lions left in Africa are in West Africa, where they are classified as Regionally Endangered. He comes to some worrying conclusions when analyzing CITES statistics for lion hunting trophies and live lion exports. When considering CITES statistics for exports of lion trophies between 1999 and 2008, he notes that as numbers of canned lion and/or captive bred lion trophy exports from South Africa increased, the number of wild lion trophy exports from five other African countries decreased, which on the face of it appears to support the notion that captive bred lion hunting eases the pressure on wild lions.

However, one proponent of the argument, who assisted the South African Predator Breeders Association in their appeal against certain TOPS regulations, concluded that, were it not for captive bred trophy hunting, there would be less than 15 wild lions available to be hunted in South Africa every year. Hargreaves notes that 15 is the maximum number of suitable wild trophy lions likely to be found by hunters annually. The problem is that this figure is far lower than the official CITES average of 163 non captive bred (i.e. wild) lion trophies exported from South Africa annually throughout the ten year period. One explanation could be that, during this time, many captive bred lions were in fact relocated to fenced areas that could be deemed to allow the animal to be self-sufficient in a natural area, and then killed and labelled as “wild”.

Kelly Marnewick states that she has received unconfirmed reports of a rather dubious scenario. “If a hunter is hunting in Zambia, for example, and he is unable to find a lion - which he has a Zambian permit to hunt - within the time frame of his visit, an unethical outfitter may find a captive bred lion for him in South Africa. This lion is then smuggled into Zambia and hunted, and later the trophy is exported, all on the Zambian permit. This sort of thing makes a mockery of the permit system and confuses CITES quotas. We don’t know how often this may be happening.” Hargreaves also mentions a scenario where a corrupt hunting outfitter will have a captive lion exported from South Africa to another African country before the hunt takes place. He says in a report: “The animal will be drugged so as not to travel too far and it will then be shot and exported from another country as ‘wild’ .” As a matter of interest, over a quarter of live captive bred lion exports from South Africa were to other African lion range states including Botswana and Zambia. The sharp increase in live lion exports supports the fact

that captive bred lions are being exported from South Africa to other African lion range states from where they are being hunted and exported as ‘wild’ lions.

Countries such as Mozambique, Zambia and Zimbabwe have comparatively fragile wild lion populations whose continued existence remains uncertain. The wild lion exports from these countries from 1999 - 2008 declined in recent years. In Tanzania, it has been concluded that this downward trend most likely reflects declining population sizes. In fact, one of Hargreaves’ sources comments that “professional hunters working in Africa have observed over the past several years that suitable trophy male lions have become increasingly difficult to find and that prides are smaller and unstable with fewer cubs being produced and fewer individuals surviving to adulthood.” If the captive bred lion element were removed from Botswana, Mozambique, Zambia and Zimbabwe’s official wild lion trophy export figures, these would be far lower. Should such countries continue to submit lion trophy export figures that are in effect bolstered by captive bred lion trophies being passed off as ‘wild’, this would create the impression that these countries have much higher lion populations than is actually the case. This could lead to continued or excessive authorization of trophy hunting permits in places where lion populations are close to extinction and/or the diverting of conservation measures that might otherwise have been taken.

Recent evidence and media reports suggest that some captive lion breeders in South Africa are now also exporting the bones from their lions to China for use in tiger bone wine, in addition to conducting their usual trophy hunting operations. Asian demand for lion bones is directly linked to the demise of the tiger. According TRAFFIC’s report Taming the Tiger Trade - China’s markets for wild and captive products since the 1993 domestic trade ban, China rapidly went from being one of the range states with the highest tiger numbers to the least. Factors for the tigers’ precipitous decline include human population growth, habitat loss and fragmentation, and the depletion of the tiger’s wild prey. The cats were also intensively hunted as pests during the 1950s and ‘60s. The tiger has been protected since 1979 as a Category I species, affording it maximum protection from the hunting, sale, purchase and use of tigers and tiger products.

Another major cause of the tiger’s decline was the use of its bones and body parts in Chinese traditional medicines. Chinese medicine has ancient roots and is still preferred to modern, Western medicine. The

most traditional form is dried, fried tiger bone, ground to a powder in small amounts for mixing with other ingredients. Tiger bone wine is the most famous medicinal preparation, used to treat rheumatism and other ailments, and has been brewed since the Han dynasty. Before the 1993 ban, 1 000 - 3 000 kg of tiger bone was used annually in traditional medicine production, especially wine, supplying 80% of the Chinese domestic market. Today, tiger wine is no longer regarded as medicinal and is considered a tonic.

The tiger bone used in these medicines came from wild Asian tigers. In the 1960s, around 300 tigers were removed from the wild annually, providing some three metric tons of bone. The harvest declined over the next two decades, reflecting the decline of these animals in the wild, although 1 000 kg of tiger bone a year was still used for traditional Chinese medicine. In 1992, immediately prior to the ban, stockpiles increased to over two metric tons and tiger bone pharmaceutical production rose to meet demand.

After China joined CITES in 1981, the tiger was listed on Appendix I, prohibiting international commercial trade. No official records of tiger imports were recorded after this but the manufacture of Chinese medicines persisted. It was concluded that the requisite tiger bones and parts were coming from tigers poached from other range states and smuggled into China. International concern over poaching grew and China stepped up its legal protection of the creature, prohibiting the use of tiger products in traditional medicines. Stocks of tiger bone were declared government property and sealed. CITES undertook stringent measures to halt the trade. Yet it continued. There was growing evidence that, as numbers of wild tigers continued to drop and illegal trade in tiger parts became more difficult, other Asian big cat

species such as leopards were being used as substitutes. At present, captive bred tigers within China are also thought to be supplying the illegal tiger bone medicine market.

But not all the raw materials for tiger bone wine are coming from the Far East. According to the TRAFFIC report, a Chinese company received State permission to manufacture 400 000 bottles of “bone strengthening wine”- a name that sounds very similar to tiger wine in Chinese - and the product is in fact packaged in a tiger-shaped bottle. The company’s web site touts the wine as being an aphrodisiac and rheumatism curative. Although the name and packaging are reminiscent of tigers, the approved wildlife ingredient is listed as African lion, Panthera leo. There are captive lion facilities in China; one claims to have as many as 200 lions, although visitors recall seeing few animals. It is believed that other companies are also manufacturing tiger bone wine using lion bones, although the wildlife ingredient is referred to by its scientific name on labels that infer tigers; many purchasers would not realize that the content label refers to African lion or that lion bones are being used as the raw ingredient. The products are mainly sold through gift shops and tourist outlets.

The report states that the manufacture of wine labelled as containing lion bone but being marketed as implicitly containing tiger bone violates both Chinese national and international laws. The lion is listed on CITES Appendix II, which permits international trade with an export permit. China has not reported any exports of lion bone wine to CITES. The sale of lion bone wine, while not encouraged by conservationists, is technically legal; however, if it was found that the wine was manufactured with tiger bone being passed off as lion bone, this would be illegal. The report further recommends that lion bone not be used

Tigers have been hunted almost to extinction in China and other parts of Asia in the quest for traditional Chinese medicines and tiger wine (inset), a tonic, made from tiger bones and carcasses.

as a substitute for tiger bone in the making of these wines, as this could serve to stimulate demand, which may potentially impact wild lion populations.

Karen Trendler says: “There are very strong indications based on various reports and research into the wildlife trade that providing lion bone will stimulate demand because businesses and a supply chain develop around a product and then this has to be sustained and demand increases. Historically, many Asian countries do not purchase legally from other suppliers but prefer to farm their own product or go the black market route. Tiger farming has not in fact saved wild tigers and breeding conditions are appalling. Lion could well go this way as there is nothing preventing the export of lion for captive breeding in Asian countries, which are already breeding tigers and rhinos.”

Lion carcasses in particular are in demand (whole carcasses are steeped in vats to create the wine). Kelly Marnewick says: “We are concerned about the possibility of lion bone becoming a commodity in South Africa. At present, a lion skeleton would fetch around R30 000.” According to some media reports, a complete lion carcass could fetch as much as US$10 000; charity Lion Aid mentions a figure of around US$15 000. Either way, lion carcasses fetch tremendous amounts of money. Prior to this eventuality, hunting outfitters usually buried or burned lion carcasses, which they had no use for. There have even been media accounts of breeders digging up old, previously buried carcasses in order to sell them.

When questioned on the issue, PHASA said that it could not comment, as this fell outside its jurisdiction. Herman Els said that he does not know how many hunting outfitters are involved in the lion bone trade. However, he did say, “90% of the problem is that lions are not being policed. Lions are worth more in pieces. Lion claws and lion fat are sought after by traditional healers. The most important lion part is the floating collar bone, which is believed to enhance power and bring luck. There is starting to be a local market for lion parts. But by far the biggest market is in the Far East.” He adds, “This thing with the lions is unbelievably disconcerting. The social status attached to wild animals in Asia needs to change.”

Rynette Coetzee says, “Many lion breeders are moving into the lion carcass market. From a legal point of view, they need only prove that the carcass was legally acquired. Often the hunter only wants the trophy parts - the skin and head. If the hunter gives the outfitter the rest of the carcass, there’s no prohibition on the outfitter taking it. The government only wants to see that the lion was hunted on a permit.”

Richard Hargreaves comments in his report on the issue, stating that, “far from clamping down on the new lion bone trade, thus sending a clear signal that it will not tolerate any further derogation of its reputation by the captive lion breeding industry, the South African government has taken an extraordinarily acquiescent and even supportive stance.” He also raised concerns that, should hunting outfitters move from trophy hunting to the supply of carcasses, the incentive for creating fine-looking trophy animals would be removed. “Breeders diversifying down this route are likely to move towards the cheapest possible production of bone by way of unnaturally fast, hormonally enhanced growth of their lions to

The Asian tiger and the African lion - linked by a strange and almost macabre twist of fate. Will the African lion go the way of the tiger, confined to inhumane wildlife farms to satisfy Asian medicinal demands?

adulthood and then starving them to death as per the photographs of skeletal tigers languishing in Chinese tiger farms.”

This trade also carries the obvious risk of not only creating but actively fuelling the demand for lion bones from Africa. Hargreaves says that merchants may well choose to buy wild lions from poachers selling them for much lower prices than their captive breeder rivals are charging. This could conceivably increase the risk that lions would go the way of the rhino - endless poaching and a continued countdown to extinction in an inexorable downward spiral. Some media reports are already urging lion owners to start considering ways to protect their

lions, should the lion bone trade catch on in a big way. Whichever way you look at it, the increase in such a trade, together with the captive lion breeding industry that sustains it, could well serve to ultimately seal the fate of the wild lions of Africa.

Special thanks to Rynette Coetzee and Kelly Marnewick of the Endangered Wildlife Trust for taking the trouble to provide us with copious information, documentation and sources, to Dr Herman Els for speaking to us at length on the phone, and also to Karen Trendler, for giving input at short notice.