Noni Lazaga€¦ · en el exterior, el paisaje de Fuenlabrada, que actúa como una posible salida....

Transcript of Noni Lazaga€¦ · en el exterior, el paisaje de Fuenlabrada, que actúa como una posible salida....

NONI LAZAGA

La casa del Laberinto

The House and the Labyrinth

La Casa del Laberinto/ The House and the LabyrinthNoni Lazaga

Exposición organizada por/ Exhibition organised byCEART, AYUNTAMIENTO DE FUENLABRADA Y CASA ASIA

CEART:facebook.com/cultura.fuenlabradaCentro de Arte Tomás y Valiente-CEARTC/ Leganés,51.28945. Fuenlabrada. Madridwww.ceartfuenlabrada.es

Comisariado/ curatorshipMenene Gras Balaguer

Textos/ TextsMenene Gras BalaguerNoni Lazaga

Fotografías/PhotographiesFelix LorrioNoni Lazaga

Impresión/PrintingGráficas Caroal

ISBN CEART: 978-84-606-9862-3Depósito Legal: M-33342-2015

© De las obras: Noni Lazaga ( A.Muñiz)© De las fotografías: sus autores© De los textos: sus autores

Queda rigurosamente prohibida, la reproducción total y o parcial de esta obra por cualquier medio o procedimiento, sin la autorización escrita de los titulares del copyright, bajo las sanciones establecidas en las leyes.

Notas sobre el proyectoNoni Lazaga

Trabajo como un afinador modificando y ajustando los puntos en el espacio; ya no veo las escaleras, ni las columnas ni siquiera la ventana, solo veo los puntos que me permiten dibujar, escribir en esa hoja infinita que ya no es de papel, sino de un espacio que vacío por momentos, para que la invisibilidad del aire sea tridimensional.

Cada construcción debe sostenerse a sí misma para que sea transitable, só-lidas en los gaseoso; desde fuera todas deben flotar en ese espacio vacío, invisible, como el ritmo de una caligrafía kana. Solo así el medidor de incer-tidumbres tendrá un sentido visual, de otra manera las caligrafías supondrán borrones, manchas que no permitirán leer cada elemento.

Liberar el pensamiento y dejarse llevar por las infinitas metáforas que se pier-den en el silencio, en el vacío, en lo invisible, en la nada. Un espacio simbólico. La ficción es el único mundo posible; un sueño enlaza con otro sueño, una irrealidad tras otra construyen la casa, el ser, que transita desde un espacio pasado a un espacio futuro donde el tiempo nunca es lineal.

Materiales: el vacío y la lana, entendida esta, grafito de color que dibuja en el aire, en el vacío que sustituye al papel. La lana y sus diferentes grosores y calibres me permiten la elasticidad en las arquitecturas. La tinta se convierte en línea de lana en el espacio.

Formas:La línea como dibujo expandido, contiene en su interior las caligrafías: kanji, kana y árabe. La tridimensionalidad del trazo caligráfico oriental abstraído, se comprime finalmente en la lana, de color negro y de color rojo, utilizada como trazo y como material flexible que dibuja y construye.

Espacio: No existe culto al espacio. Lo concibo como una hoja infinita de papel invisible, con saltos e imprevistos, con elementos que ayudan o entorpecen la acción de la línea. Elementos traspasables. Modificarlo, abarcarlo, plegarlo, son actos es-paciales. La construcción del vacío requiere invisibilidad, cada vez tengo más dudas sobre la existencia del vacío. Distingo entre lo visible y lo invisible, pero solo en lo que refiere a la percepción con las herramientas que poseo como ser humano. Dentro de lo invisible, de lo lleno que no se ve, construyo, modulo, dibujo.

21NONI LAZAGALa Casa del Laberinto

COLECCIÓN CEART N 52 CEART COLLECTION

22

Abre la exposición, una fotografía de la serie la era gaseosa, que remite al mo-mento actual. Estructuras imposibles de habitar que anuncian un nuevo para-digma sobre el ser humano en un mundo que parece disolverse en estructuras desconocidas. Lo sólido, lo conocido, se convierte en lo que no se ve. Nada es lo que parece. Mundos ficticios se suceden construyendo la casa, el ser, en diferentes laberintos individuales. El recorrido de la exposición sigue una narrativa a través de números, el orden no es aleatorio; pero el visitante puede recorrer las piezas también de forma anárquica sin seguir los números, según su criterio. El público lo concibo de forma activa, como partes de la caligrafía, trazos que escriben en movimiento su recorrido individual en el espacio. Cada persona posee su propio laberinto, que traslada a través de las piezas en un ejercicio de búsqueda sin respuestas concretas. Solo la incertidumbre es una realidad.

Generalmente abordo los proyectos uniendo estéticas complementarias, orien-tales y occidentales y elementos de ambas culturas: Asimetría frente a simetría, multicentro en oposición a centro, geometría procedente del espacio caligráfi-co, vacío frente a lleno, multiverso frente a universo.

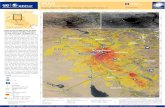

En el pasadizo (1) hay dos salidas: La primera suficientemente amplia, hasta la que se puede llegar acompañado y conduce a la casa de muñecas (2) una casa sujeta al cristal e inmovilizada. A través del gran ventanal de la casa aparece como un eco amplificado el paisaje de edificios de esa otra supuesta realidad en el exterior, el paisaje de Fuenlabrada, que actúa como una posible salida. La casa de muñecas anclada en un pasado metafórico, coja y vacía, actúa como contendor de experiencias anteriore, vivenciadas, el único elemento sólido de la exposición, junto al espejo (4).

La segunda salida del pasadizo se estrecha y permite salir solo individual-mente. Su relación con el camino zen está presente. Los preliminares de esta construcción en lana negra se encuentran en las hojas del libro espacial que hice en 2012 y en las arquitecturas elásticas que realicé en papel (washi) por primera vez cuando vivía en Japón en 1999.

El pasadizo es la suma de esas hojas que levantan una arquitectura que atra-viesa el techo y será transitada por el público como si estos fuesen kanjis, o caracteres, en el espacio. Formalmente acoge a la pared, con un movimiento orgánico, y podría continuar más allá de sus muros de forma elíptica. Existe una tercera vía, que permite ver el pasadizo desde fuera, sin entrar en él.

La casa se pliega en el espacio (3); construida con línea roja define el paso del visitante a través de muros invisibles que generan tensión ante el miedo a la nada y la duda de si se está dentro o fuera.

Planos vacíos que se pueden/deben traspasar si se quiere acceder a las esca-leras que conducen al primer piso y al espejo (4). La ventana ciega se sitúa en medio de la estancia, una ventana construida con una veladura que nos remite nuevamente a nuestro propio pensamiento.

En el espejo, que no refleja, (4) la realidad es inaccesible y los verdaderos rostros no existen, sino que otras irrealidades devuelven la imagen del no yo. La ficción es el único mundo posible. El espejo actúa como otro elemento sim-bólico, las figuras aparecen distorsionadas deliberadamente a causa del ma-terial elegido, un metacrilato, con el que crear un mundo futuro de sueños que complementa la casa de muñecas. La línea azarosa al pie del espejo señala el caos, parte esencial de la construcción, de la irrealidad, del sueño. El caos anudado en numerosos caminos señalan un futuro irreal tan posible como los ya definidos.

El medidor de incertidumbres (5) cubre una parte del espacio pero es importan-te mantener la vista desde el primer piso; eso significará haber llegado al final del recorrido, haber salido de nuestro propio laberinto y llegar a la percepción completa de la casa, el ser, para entender que el techo protector no es sino el medidor de incertidumbres, que reduce al individuo en el momento actual a una mera gráfica estadística. Como su nombre indica es un juego de palabras que se contradicen creando un significado nuevo (Oxímoron).

Ficha TécnicaLocalización en la exposición y en catálogo. 0. La era Gaseosa 1. Fotografía sobre ecotex. 70x100 cm. pp 54-551. El pasadizo. Lana,acrílico+vacío. 270x380x850 cm. pp 27,48-49, 50-51, 52-532. La casa. Madera+cristal+lana, 100x80x140 cm pp Cubierta interior3. Ventana ciega en habitación roja. Lana+acrílico+vacio. 270x340x850 cm. pp 16-17, 18 (detalle)4. El espejo. Metacrilato+ lana. 300x200 cm. pp .8, 15,20,285. Medidor de incertidumbres.Techo. Lana+vacio. 900 x medidas variables x 2600 cm. pp: 3, 4-5,6-7,8-9,10-11,12-13,14- 15,19 (detalle),49

23NONI LAZAGALa Casa del Laberinto

COLECCIÓN CEART N 52 CEART COLLECTION

24

Notes about the projectNoni Lazaga

I work as a tuner, modifying and adjusting dots in space; I can’t see no more the stairs, the columns not even the window, I see only the dots that allow me to draw, to write in this infinite sheet that is no longer made of paper, but of a space that I empty at times, in order for the invisible air to become three-dimensional.Every construction must sustain itself in order to be transited, solid in the ga-seous; seen from the outside, all of them must float in this empty, invisible spa-ce, just like the rhythm of a Kana calligraphy. Only in this way the uncertainty meter will have a visual meaning, otherwise the calligraphies will become smud-ges, blots that will not enable the reading of every element.

Freeing the mind and letting oneself be carried by the infinite metaphors that are lost in the silence, in the void, in the invisible, in the nothingness. A symbolic space. Fiction is the only possible world; a dream links to another dream, one unreality after the other build the house, the being, which transits from the past into a future where time is never linear.

Materials: The void and the wool, this last one understood as colored graphite that draws in the air, along the vacuum that stands in for the paper. The wool and its diffe-rent volumes and calibers allow for elasticity in my architectures. Ink becomes a line of wool in the space.

Forms: Line as an expanded drawing, containing calligraphies inside: kanji, kana and Arabic. The three-dimensionality of the abstracted Oriental calligraphy stroke is finally compressed in the wool, in black and red colors, used as both stroke and flexible material to draw and build.

Space: There is no cult of space. I see it as an infinite sheet of invisible paper, with jumps and hurdles, with elements that help or hinder the action of the line. Elements than can be passed through. Modifying it, encompassing it, bending it, those are spatial acts. Constructing the void requires invisibility; each time I have more and more doubts about the existence of the void. I distinguish bet-ween the visible and the invisible, but only in what concerns perception with the tools I have as a human being. Within the invisible, within the fullness unseen, I build, modulate, draw.

25

Opening the exhibition, a photograph from the gaseous era, which remits to the present moment. Structures impossible to inhabit that announce a new para-digm about the human being in a world that seems to dissolve in unknown struc-tures. What is solid, what is known, becomes that which is not seen. Nothing is what it seems. A succession of fictional worlds that build the house, the being, in different individual labyrinths. The exhibition route follows a narrative through numbers, the order is not randomly chosen, nonetheless the visitor can also go through the pieces in an anarchic way, without following the numbers, following his criteria. I perceive the audience to be active, as parts of the calligraphy, strokes writing in movement their individual paths in the space. Every individual possesses its own labyrinth that transfers to the pieces by engaging in a sear-ching exercise without specific answers. Only uncertainty becomes reality.

I tend to approach the project unifying complementary aesthetics, Western and Eastern and elements of both cultures. Asymmetry instead of symmetry, mul-ticentre instead of centre, geometry from the calligraphic space, empty versus full, multiverse versus universe.

In the passageway (1) there are two exits: The first one, wide enough, can be reached accompanied and leads to the dollhouse (2) a house fixed to the glass, immobilized. Through the large window of the house shows, as an amplified echo, the landscape of buildings of that other reality in the outside, the Fuenla-brada landscape, acting as a possible exit. The doll house pinned in a metapho-rical past, limp and empty, acts as a container for gone-by experiences, lived, the unique solid element of the exposition, altogether with the mirror (4).

The second end of the passage narrows down and it can only be walked through individually. Its relation with the Zen path is present. The preliminary sets of this construction in black wool are found in the pages of the spatial book I made in 2012 and also in the elastic architecture that I made of paper (washi) for the first time while in Japan in 1999.

The passage is the addition of these leaves, which raise the architecture and get through the ceiling, to be later transited by the public as if these were kanji, or characters in the space. It formally receives the enclosure, with an organic movement and could, in an elliptical form, continue far over its walls. There is a third way that allows seeing the passage from the outside, without entering it.

The house bends itself on the space (3); built with red line, it defines the walking of the visitor through invisible walls that generate tension because of the fear to nothingness and the doubt of whether one is outside or inside.

NONI LAZAGALa Casa del Laberinto

COLECCIÓN CEART N 52 CEART COLLECTION

26

Empty planes that can/must be passed in order to reach the stairs leading to the first floor and the mirror (4). The blind window is located in the middle of the room, a window that again remits to our own thinking.

In the mirror, that does not reflect, (4) reality remains inaccessible and actual fa-ces do not exist, but other unrealities give back the image of the not-self. Fiction is the only possible world. The mirror acts as another symbolic element, delibe-rately distorted figures disappear due to the chosen material, a methacrylate, which is used to create a future world of dreams that complements the dollhou-se. The hazardous line at the bottom of the mirror points out at the chaos, es-sential part of the construction, of the unreal, of the dream. The chaos knotted in numerous paths signals an unreal future, as possible as those already defined.

The uncertainty meter (5) covers a part of the space but it is important to keep it in sight from the first floor; this would mean having reached the end of the pas-sage, getting out of our own labyrinth and having a complete perception of the house, the being. A full perception needed to understand that the protecting cei-ling is nothing but the uncertainty meter, reducing the individual at that moment into a mere graphic statistic. As its own name indicates it is a play of words that contradict each other, creating therefore a new meaning (oxymoron).

Data sheetLocation at the exhibition and in the catalog. 0. The gaseous era 1. Photography on Ecotex. 70x100 cm. pp 54-551. Passageway. Wool, acryllic+void. 270x380x850 cm. pp 27,48-49, 50-51, 52-532. The dollhouse. Wood+glass+wool, 100x80x140 cm pp. Inside cover.3. Blind window in a red room. Wool+acrylic+void. 270x340x850 cm. pp 16-17, 18 (detail)4. The mirror. Methacrylate+wool. 300x200 cm. pp .8, 15,20,285. Uncertainty meter. Ceiling. Wool+void. 900 x variable measures x 2600 cm. pp: 3, 4-5,6-7,8-9,10-11,12-13,14- 15,19 (detail),49

TEXTO Noni. Inglés

NONI LAZAGALa Casa del Laberinto

28

La Casa del Laberinto Menene Gras BalaguerComisaria del proyecto

La casa del laberinto es un enunciado que indica o supone la existencia de una casa situada en un laberinto, sin especificar de qué casa se trata ni en qué laberinto se ubica. Esta indeterminación potencial es la que introduce el posible acontecer y la construcción de un hecho del lenguaje, cuya represen-tación sensible se produce como apertura al mundo, sin necesidad de que su reconocimiento sea una condición para abordarlo. Los hechos del lenguaje pueden o no corresponderse con una realidad a la que tengamos acceso a través de los sentidos, siendo más importante entender cómo se organizan las palabras y la estructura de la frase y detectar el significado de cada uno de los elementos que entran en relación a través de una combinatoria que propone una existencia nueva cuya percepción pertenece al dominio de la imaginación. La artista, en este caso, se identifica con el hablante, en tanto que sujeto rela-cional que alumbra un mundo a través del lenguaje –en este alumbrar o dar a luz, se establece la posibilidad de que las unidades portadoras de significado adquieran la capacidad de generar mundos de mayor o menor complejidad que demuestran la relación entre el sujeto del habla y el lenguaje, y cómo éste no puede existir sin el primero, que es el que organiza sus elementos para producir la relación entre la palabra y la cosa, mediante el signo lingüístico.

Casa y laberinto al asociarse entre sí mediante un artículo y una proposición en este orden estimulan juntas y por separado en la imaginación una suce-sión de imágenes como lo harían otras asociaciones que son características de los haikus japoneses, lluvia y otoño, viento y árbol, noche y nada, agua y pájaro, nube y ocaso. El “como” sin nombrarse es el vínculo invisible que establece la comparación entre términos dispares introduciendo el sentido –como las hojas de té, como las piedras, como la humedad que lo impregna todo, como la muerte y la flor, como el aire, como la nada, como la luna o el cangrejo. El número de posibilidades es infinito, porque la combinatoria a la que puede dar lugar el hablante carece de límite, como se evidencia en esta forma poética y en la poesía en general. Las palabras son como piedras a las que el hablante da vida, al activarlas para comunicarse. A través suyo se convierten en elementos sonoros que llegamos a escuchar como si tuvieran vida propia y a través del oído los relacionamos con todos los demás sentidos.

El proyecto expositivo que ha derivado en la intervención espacial de Noni Lazaga es una propuesta de instalación para un espacio hostil, que más bien se resiste a ser intervenido dada su peculiar arquitectura, cuya presencia se impone como sucede en otros muchos centros de arte o museos destinados

29NONI LAZAGALa Casa del Laberinto

a la presentación de obra de artistas contemporáneos o a la intervención por-parte de aquellos artistas que trabajan preferentemente con el espacio. Para familiarizarse con el lugar, la artista realizó varias visitas con el fin de investigar el espacio y su entorno, haciendo mediciones y calculando distancias entre muros, puertas, ventanas y techos. Entendiendo el desafío que representa-ba su actuación, optó por una propuesta de intervención que debía transfor-mar este lugar de tránsito, concebido como un “entre” que hace las veces de intercambiador entre la planta baja y la segunda planta, en una construcción conceptual, cuya expresión simbólica fuera lo bastante ambigua para activar narrativas sin condiciones para sus interlocutores o habitantes temporales. La instalación resultante de su ocupación del recinto está precedida de la obser-vación detenida de aquellos puntos invisibles que se relacionan entre sí en cualquier espacio, indicando la multiplicidad direccional de las fuerzas que se pueden registrar como consecuencia, a raíz de su conexión. No era fácil pro-gramar una estrategia para intervenir el espacio que se le había adjudicado, pero la artista lo ha resuelto aplicándose la condición de huésped que hace el esfuerzo de adaptarse a un entorno dado. Adecuar y ajustar el dibujo al espacio, haciendo que la línea introduzca la temporalidad en la espacialidad, sin olvidar el impacto visual necesario para que su función se reconozca ha sido la clave de su intervención. La nave híbrida en la que se ha circunscrito su instalación se expone a la mirada efímera del observador que la habita al in-troducirse en su interior, sin que éste logre abstraerse del entorno circundante.

En un espacio de tránsito como el mencionado, la artista decidió dibujar otro espacio, como si se tratara de recuperar los márgenes de este conte-nedor abierto y sin definición y transformarlos en un marco específico ha-ciendo las veces de límite para vencer asimetrías y tensiones. Para llegar a suspender el dibujo en el aire, optó por invadir el espacio aéreo o vacío contenido entre las demarcaciones impuestas por muros, escaleras y te-chos, oponiendo resistencia a la fuerza de gravedad. Todo empieza en el dibujo y la línea, entendida como la suma de puntos, equivalentes a la uni-dad indivisible que la forman, en una dirección que tensa las distancias y evita de oficio las curvas. Durante la estancia prolongada que hizo en Ja-pón en la década de los 90 pudo comprobarlo sensiblemente, cuando seinició en la caligrafía japonesa. La analogía entre el dibujo y la caligra-fía reside en el hecho de que dibujar y escribir tienen en común el uso de la línea, de manera que las caligrafías china y japonesa interiorizan el dibu-jo como elemento fundador de la belleza del trazo, los ideogramas en Chi-na y los kanji –grafismos que exigen gran precisión y exactitud en el trazo para transmitir lo que pretenden comunicar- en Japón. A esto, cabe añadir los preceptos metafísicos de la cultura tradicional de cada país y la téc-nica indispensable para su realización. La caligrafía japonesa o Shodo se identifica con el camino de la escritura –la escritura es un camino que

COLECCIÓN CEART N 52 CEART COLLECTION

30

avanza en el vacío creando la presencia del habla y dando lugar al sentido- yprocede de la caligrafía china con la que comparte sus raíces, que pene-tró en Japón a través de Corea en el siglo IV. La artista consigue algo que puede parecer tan inverosímil como caligrafiar el espacio, significándolo, tras hacer múltiples mediciones y cálculos entre puntos invisibles, para descu-brir conexiones que convierte en puentes de unión que la mirada atraviesa.

Como en anteriores proyectos, el culto a la cultura japonesa reaparece en la in-tervención de Noni Lazaga en el CEART, demostrando que si bien sus antece-dentes son de una complejidad extrema, la experiencia de su estancia en Ja-pón, haciendo el aprendizaje de la lengua, la cultura del papel y de la tinta del que nacieron dos libros, “La Caligrafía japonesa” (Hiperion, 2007) y “Washi. El papel japonés” (Ed Clan, 2da ed, 2014), constituye un precedente inédito que no puede obviarse, pese al tiempo transcurrido. La afinidad de la artista con esta cultura se ha filtrado en su obra desde entonces, derivando en conexiones múl-tiples como las que ella dibuja en el espacio inventando líneas para contener el vacío y decir que “está ahí”, que el vacío es el principio y el fin del mundo sen-sible. Su propuesta responde a un interés manifiesto por los valores estéticos de una cultura que no considera en las antípodas de occidente, sino que cree posible integrar en su modo de concebir el mundo, debido a los vínculos exis-tentes entre oriente y occidente desde la Antigüedad. De ahí procede tambiénsu insistencia en abordar la relación entre arte y lugar, arte y acontecer, como ha venido desarrollando en su obra y en su trayectoria, mediante una poética de la deconstrucción de lo dado que introduce la abstracción geométrica de sus figuras espaciales, como en “To Dream or not to Dream“ (Soñar o no soñar en sustitución del ser o no ser de Hamlet), un proyecto que precede a éste y que presentó en la Galería Protea de San Diego (abril-mayo, 2013) y en el Instituto Cervantes de Nueva Delhi (febrero-marzo, 2015), donde la artista adoptaba el espacio a modo de lienzo, y el aire como materia, en tanto que una aplicación más del concepto ampliado de dibujo expandido, que continúa reinterpretando.

No obstante, tal vez sería oportuno hacer referencia más bien a una posible caligrafía expandida en el espacio, a través de la cual la artista escribiría en un idioma de su invención distanciándose de los signos convencionales de cual-quier lenguaje al uso. De este modo, la acción se completaría en una especie de circularidad, que en su obra conduciría de la caligrafía al dibujo y de éste a la caligrafía de nuevo, cerrando el círculo. Dibujar el espacio sería entonces caligrafiarlo y por lo tanto la acción de dibujar equivaldría a escribir. En amboscasos, se hace camino –de la vida a la muerte y a la vida, sin que nunca se pueda poner fin a este andar que se asocia con él. La noción de camino forma parte de la definición del Budismo zen, en la medida en que éste es a la vez una concepción de la vida y del cosmos, procedente originariamente de India y China, que a partirdel siglo XII arraiga en Japón. Este camino es un “camino de liberación” que

31NONI LAZAGALa Casa del Laberinto

reinterpreta el Tao y se identifica con el camino de la iluminación del ser huma-nopara alcanzar el satori, una experiencia mística para occidente a través de la cual se alcanza la vacuidad, que se asume como el principio de todas las formas del ser y de la nada. El Zen extiende su influencia en todos los dominios de la vida cotidiana en Japón, y de ahí que siga siendo tan popular. Fue la re-ligión de los samuráis, promovida por los primeros shogunes, y su popularidad se debe a su presencia en la poesía, la pintura, la caligrafía, la arquitectura, la artesanía, la ceremonia del té, el ikebana, la enseñanza y los monaste-rios. Pero, lo que trasciende es que este camino de liberación sea equivalente al proceso por el cual se adquiere el conocimiento de la realidad del mundo.

La escritura del espacio no necesita para ella un soporte como la hoja de papel, porque puede hacerlo evitándolo, ya que carece de alfabeto y su gesto es com-parable al del calígrafo japonés que sí en cambio presta atención a la precisión del trazo y al gesto del signo lingüistico que es de su invención. Sus dibujos son espaciales y transforman cualquier lugar dado en otro que al apropiarse convier-te en territorio. Ella dice -“Nada es lo que parece”- y la demostración sensible de esta afirmación que nombra el engaño de los sentidos son sus aeroflexias, sus dibujos aéreos y sus arquitecturas elásticas. Formas del aire sin forma que ha creado en el transcurso de su trayectoria y que retoma en este proyecto exposi-tivo como método de trabajo, activándolas de nuevo sin prejuicios, a la hora de enfrentarse con el enorme vacío percibido por ella. Prescindiendo del soporteconvencional del dibujo, diseña arquitecturas en un espacio semántica-mente ya significado, trazando con el hilo geometrías ingrávidas que el ojo ocupa y habita. Son dibujos que forman hipotéticos planos en el espacio hechos con hilos, como si se tratara a su vez de escrituras que componen jeroglíficos elementales que evocan la fragilidad de construcciones incon-clusas. La red de relaciones espaciales generadas entre estas líneas y sus diferentes puntos de apoyo en paredes, techo y suelo ponen en tensión lu-gares de un lugar que se exponen a lecturas del espacio habitable a través de sus extensiones desafiando los límites convencionales de su aparecer. El camino es el concepto que estructura la instalación concebida por la artista para intervenir este espacio anodino comparable como se ha dicho a un inter-cambiador o distribuidor, porque en realidad es una zona de paso de la segunda planta que comunica la planta baja y la tercera planta, y ambas con las oficinas integradas a continuación de este pasillo. Noni Lazaga ha dibujado un camino que llama “pasadizo”, replicando las acepciones del término “camino”, cuya razón de ser es la de conducir de un lugar a otro lugar al transeúnte, aludiendo a la temporalidad del habitar y por lo tanto a la existencia de todos los se-res vivos. Este camino se convierte en una construcción geométrica abstractacon los hilos que ella dispone, de manera que el visitante pueda atravesarlos como si se tratara de una prueba, cuya superación equivale a explorar el lugar y

COLECCIÓN CEART N 52 CEART COLLECTION

32

aceptar las condiciones para llegar a la casa que se encuentra al final del labe-rinto. El espacio queda intervenido, planteando interrogantes que no siempre se responden para aquel que decide hacer la travesía, por entender que el recorri-do del pasadizo es un “ir a través”, para llegar a otra parte, desde que se acce-de al espacio expositivo. Se ha optado por identificar el camino con un laberin-to, porque el primero es aquí un espacio trazado simbólicamente que se resiste a ser interpretado como un mero espacio de tránsito. La figura del laberinto se identifica con una red o encrucijada de caminos presente en todas las culturas, y con frecuencia asociado a rituales de iniciación que implican la superación por etapas para alcanzar un centro, en el que se representa epistemológicamente la imagen de una transformación del hombre, y la verdad del ser y del existir.

El círculo hermenéutico que para Heidegger encajaba la reciprocidad entre el comprender y el existir, y entre texto y contexto, identifica el recorrido que con-duce a la casa que se alcanza al final del camino, apareciendo ante el sujeto del habla. Es el símbolo de la morada y del habitar, que remite a la idea primigenia del construir, habitar y pensar heideggeriano. Paradójicamente, se identifica con el principio y el origen del ser, el lugar donde se encuentran las raíces del lengua-je; cuando se afirma que el habla es la casa del ser, no se descarta que éste es fundante del lenguaje, sino al contrario. El habla es tiempo y por lo tanto existen-cial, y se identifica con el ser en el mundo o estar ahí. La palabra se revela como la verdad del ser, y éste recíprocamente se revela en el lenguaje, que a su vez le realiza. La verdad del ser viene al lenguaje, aparece a través del lenguaje. En“¿Qué es Metafísica?”, apunta “El pensamiento, sumiso a la voz del Ser, bus-ca la palabra a través de la cual la verdad del Ser viene al lenguaje”. La casa es un símbolo del habitar que se representa en un edificio rectangular, suje-to con dos cuerdas a ambos lados de las paredes adyacentes y cuya incli-nación hace sospechar la caída aunque ésta no llegue a producirse nunca.

Es una casa de muñecas que la artista ha conservado desde la infan-cia: de dos plantas y un terrado, con una puerta de entrada y escale-ras que conducen hasta la parte superior, y en cuya fachada se abren las ventanas con y sin cortinas. La ubicación de la casa deja ver los edi-ficios de viviendas de Fuenlabrada que se encuentran en el vecinda-rio del CEART. El juego de duplicidades entre la casa de muñecas y losedificios colindantes extiende el diálogo entre el interior del Centro y la avenida principal del municipio de Fuenlabrada situado en el área metropolitana a 17 Kms. de la capital. No obstante, la casa es el único artefacto figurativo que se reconoce a primera vista y donde la mirada encuentra ayuda para la interpreta-ción de la intervención que ha hecho la artista introduciendo el sentido en un es-pacio no significado, o, por el contrario, significando el vacío en un lugar que se debe definir como un no-lugar. Para llegar hasta la casa, se ha de circular por ellaberinto dibujado en el aire, cuyos muros imaginarios insinúan la representa-

33NONI LAZAGALa Casa del Laberinto

ción del vacío a la que la artista aspira. Un vacío que para reconocerse deberepresentarse sensiblemente y ella recurre al punto y a la línea como uni-dad originaria del dibujo, es decir al grado cero al que éste se reduce.

Si se puede hablar de fases de un proceso a través del cual se ha planteado, concebido y ejecutado el proyecto expositivo propiamente dicho es porque la artista ha resuelto su intervención pensando en un itinerario y un recorrido que asume el concepto de umbral y zona de paso: si el acceso al espacio expo-sitivo se inicia al ingresar en el pasadizo, todo conduce a la casa que está al final del camino. El retorno, no obstante, lleva en la dirección opuesta hasta la construcción geométrica hecha con el hilo, de color rojo, que pretende repre-sentar una gran habitación con una ventana ciega pintada sobre el muro. El potencial interpretativo se abre ante el visitante, al interrogarse para compren-der el sentido de este lugar que sigue haciendo referencia a un habitar que sólo se activa en su presencia. La estancia vacía hospeda transitoriamente a quien se introduce en su interior, sólo vallado por uno de los lados, invitando a ser atravesado. Los muros imaginarios son invención del transeúnte anónimo que asocia el habitar con un refugio cerrado donde guarecerse. La artista ha querido que la visita fuera una experiencia para el sujeto que acude a contem-plar las arquitecturas que ella ha creado. Una experiencia de conocimiento por la cual se le invita a ser partícipe de la propuesta que hace en función de un criterio selectivo que pone a prueba su capacidad de observación. De ahí que la prolongación del recorrido suponga acceder a la percepción y comprensión de esta gran estructura que ella denomina “medidor de incertidumbres” y que incorpora deliberadamente avanzando sobre los escalones delanteros, donde clava a diferentes alturas los hilos que cuelga desde la parte superior tocando con la barandilla de la segunda planta.

Desde el otro lado del edificio, el dibujo conforma una estructura geométrica, ni pintura ni escultura, que abre un campo relacional más próximo a la arqui-tectura, cubriendo el amplio frontal que se abre a la vista del público. Se trata de arquitecturas extremas que no se habitan, aunque necesarias para la es-peculación de formas límite que son las que transforman la percepción de los lugares construidos por el hombre. La línea aparece como el eje de un acon-tecer espacial que parece dibujar por sí misma, hasta formar una cosmografía a modo de mapas imaginarios como los que ella acostumbra a diseñar en su fantasía superponiéndola a un lago o a un cielo nublado, encima de una colina o en el campo. Su producción en este terreno es fecunda a partir del momento en que la línea dibuja el volumen sin peso ni grosor, como si se tratara de cuer-pos o formas sensibles, cuya transparencia elimina una dimensión innecesaria para la representación de un ser o estar en el mundo, que el existir desfigura, deshace o descompone. En todos, se hace insistencia en el dibujo en tanto que escritura de la forma y en todos se realiza la idea de que la línea es un

34 COLECCIÓN CEART N 52 CEART COLLECTION

acontecer del tiempo en abstracto. La facilidad con la que ella ocupa el aire, como equivalente al vacío por su indefinición, potencia el dibujo en la base de su trabajo, actualizando la vigencia de este formar en el campo del arte con-temporáneo, donde aquel no siempre se reconoce como tal al reemplazarse a menudo por las habilidades de las máquinas en una sociedad de la información que antepone la tecnología de los medios a la transformación de lo que sabe-mos en conocimiento.

Ella hace construcciones con los hilos mediante los que teje el dibujo –tejer es una actividad que anticipa la reivindicación de género, cuando el objeto es contrario a la sumisión y la obediencia y se trata de reinventar la condición de la mujer artista recurriendo a los mismos instrumentos que han servido para dominarla o someterla. Los hilos que ella escoge, negros, rojos o blancos, a modo de cuerdas o cables, son comparables a rastros de luz o puentes de unión entre islas imaginarias hechas de puntos en el espacio, que ella detecta en muros, techos o suelos, o simplemente en la atmósfera y en la naturaleza en general, y que al unirlos entre sí crean formas que de otro modo no existirían, sean cuales sean las semejanzas con formas del mundo real. El sistema de referencias en el que se apoya avala una producción que se arriesga a plantear composiciones, que en apariencia se despliegan espacialmente, sin voluntad de parecerse entre sí ni de adherirse a corrientes ni tendencias.

La historia de la abstracción geométrica desde los años 20 del siglo pasado ayuda a entender prácticas artísticas alternativas como la suya, pero lo que de verdad contribuye a su comprensión son las afinidades electivas de la artista, cuya conexión con la cultura japonesa resulta evidente aunque no siempre consciente con la misma fuerza. Esta dimensión de su trabajo no es, sin embar-go, excluyente de una experiencia más amplia, la de una vida que transcurre en diferentes lugares del mundo, de Egipto a Japón, aunque marcada por el viaje de formación que ha sido siempre el tipo de viaje que caracteriza sus desplaza-mientos. Del mundo árabe al sudeste asiático, estableciendo rutas para atrave-sar territorios y culturas, sus aproximaciones y distanciamientos se equilibran en una imaginación que almacena experiencias, que recuerda y olvida, y cuya movilidad no encuentra obstáculo. Por analogía, parece como si la experiencia del viaje se trasladara en la práctica al dominio del lenguaje y de la escritura gestual, fuente de expresión en sus intervenciones espaciales.

Retrocediendo hasta el principio del itinerario expositivo marcado por la artista, a través de las fases o etapas del camino –el pasadizo, la casa, la habitación y el medidor de incertidumbres- el final del recorrido nos devuelve al inicio en virtud del reflejo que se produce en el espejo colocado estratégicamente sobre uno de los muros. Un espejo que deforma aquello que se ve sobre la faz de metacrilato, a cuyos pies se desploma una lluvia roja de cuerdas que se anu-

35NONI LAZAGALa Casa del Laberinto

dan en el suelo en semicírculo, formando un mandala, cuya otra mitad es la imagen que se reproduce en el cristal. Aunque parece como si el espejo fuera una ventana que separa el dentro y el fuera, lo real y lo imaginario, la verdad y el engaño. Ella deliberadamente ha escogido el espejo como artefacto mágico que reflejando la realidad es también susceptible de deformarla. Tú miras al espejo y el espejo te mira a ti y todo lo que está detrás de ti o a tu alrededor y que te es dado ver gracias a la devolución que hace el espejo mediante el truco del reflejo.

El espejo es un artefacto que ha ocupado un importante lugar en la mitología y ha sido también alimento de supersticiones múltiples, como se desprende de la segunda parte de “Alicia en el país de las maravillas”, “A través del espejo”, donde Alicia se pregunta qué debe haber al otro lado del espejo y para saberlo lo atraviesa y se encuentra en una sala, donde descubre las piezas de un juego de ajedrez y un libro de poesía escrito del revés, que sólo puede leer refleján-dolo en el espejo. Sale a continuación de la casa del espejo y entra en el mundo del espejo, donde lo primero que se encuentra es un jardín donde las flores hablan. Jorge Luis Borges comentaba el miedo que le daban los espejos en la infancia, no entendiendo el misterio por el cual aquello que se coloca delante suyo se duplica reapareciendo sobre su superficie. Fundado o infundado, este miedo a los espejos se puede descifrar en la fábula “El espejo y la máscara” de este autor, o en el poema que les dedica, en el volumen “la Rosa profun-da”(1972-75) de las obras completas, donde interroga al espejo y le acusa de tener poderes mágicos, como la palabra, para duplicar y copiar todo cuanto se le pone de delante, porque “no sé cuál es la cara que me mira cuando miro la cara del espejo”. Poderes que le causan horror, ya que “cuando esté muerto, copiarás a otro / y luego a otro, a otro, a otro…”. Borges decía a menudo, estar hecho de tiempo, y lo que más le desesperaba era su irreversibilidad, no poder detenerlo ni cambiarlo, como sus “ojos muertos” y la soledad de la ceguera.

Los nudos de lana roja que se amontonan en el suelo forman un charco de san-gre, nudos de conflicto que se heredan sin resolverse y que el espejo deforma en una especie de mandala al duplicarlo. A propósito, las alusiones de la artista a esta figura retórica no son gratuitas ni aleatorias; ella relaciona el mandala con un diagrama cosmológico o representación simbólica del macrocosmos y el microcosmos, presuponiendo su universalidad, a partir del carácter espiritual y ritual que conserva desde el inicio de los tiempos. En el círculo con forma de almendra, en el que se han depositado las cuerdas rojas sobrantes de su instalación, el mandala resultante representa no el universo sino un universo en el que la artista se imagina atraída por el magnetismo de una figura de culto en muchas tradiciones -la mayoría de culturas, incluida la cristiana y la helénica se identifica con figuras mandálicas- sobre todo en las hinduistas y budistas. Las interpretaciones que se han hecho en oriente y occidente de sus variaciones son

36 COLECCIÓN CEART N 52 CEART COLLECTION

inagotables, pero la que más se adecúa a lo que la artista quiere plantear es la que hace Carl Gustav Jung en “Erinnerungen, Traüme, Gedanken” (Recuer-dos, Sueños, Pensamientos), donde este último narra que cada mañana di-buja en su cuaderno de notas un pequeño círculo, creyendo reflejar lo que siente y piensa a través de un mandala que traduce su estado de ánimo o en el que proyecta unorden interior que, al exteriorizarse, se puede visuali-zar e interpretar. Jung entendía que este pequeño dibujo le ayudaba a inter-pretar los sueños de la vigilia, porque según él un mandala integra conscien-te e inconsciente, y el mandala como arquetipo se encuentra anclado en el subconsciente colectivo. Si se considera que éste representa al ser humano y que interactuar con las figuras sensibles que lo identifican permite conec-tarse con el ser o la nada y la esencia del mundo, también resulta verosímil creer que esta figura contribuye a recuperar la unidad del sujeto fragmenta-do, mediante la práctica de la meditación y la observación detenida del dibujo desde los extremos hasta el centro, donde se concentra la energía que a su vez irradia hacia fuera hasta cerrarse el círculo o el cuadrado que lo contiene.

De hecho, el significado del mandala se asocia a su equivalencia con la re-presentación de un sistema del mundo. Un mandala presupone un centro, y aquello que lo rodea representa lo que significa. Este centro puede ser el yo y aquello que lo envuelve, o el universo, sea cual sea la forma, redonda, cuadra-da u ovalada en la que se represente. Si es el centro del universo, éste se es-tructura según lo que se entiende que ha de ser o es un orden del mundo. Hay muchas clases de mandalas y éstos se han reproducido sin cesar a lo largo de la historia y en el seno de muchas culturas, representando el macrocosmos y el microcosmos, particularmente en el budismo y el hinduismo. El mandala es para la artista un mapa de caminos que conducen al centro de uno mismo, invitando a rehacer el recorrido hacia el origen del ser y del universo. La figura del mandala evoca un laberinto, de ahí el título de este proyecto expositivo, cuyo destino es la casa de muñecas que se encuentra al fondo, de espaldas a la ventana, dejando ver los edificios de viviendas de la calle principal de Fuenlabrada, que se incorporan así al espacio donde tiene lugar la exposición.

Todo parece mirar a este centro, representado en el mandala que for-ma el charco de nudos rojos yuxtaponiéndose a su otra mitad, que se completa en el espejo, aunque el efecto óptico provocado por el refle-jo no ponga en duda su unidad, sino más bien al contrario, la afirme. Latridimensionalidad de este mandala de mandalas, o mandala expandido, respon-de a la construcción de un imaginario que une puntos en el espacio, pero a su vez el ser y el no ser del mundo, en un intento de explorar el vacío que la artista pro-pone trabajando con la espacialidad y la temporalidad de una geografía interior, donde sitúa el centro del mundo y del universo. Geografía del laberinto de nuestro inconsciente, que es el mejor símbolo de nuestra perplejidad y lugar en el que nos

37NONI LAZAGALa Casa del Laberinto

38 COLECCIÓN CEART N 52 CEART COLLECTION

perdemos irremediablemente, cuando tratamos de salir de él. En este perderse,hay un deambular necesario en busca de lo que creemos ser y a dónde vamos, atravesando espejos para ir al otro lado de nosotros mismos, y descubrir una realidad escrita del revés, que no lograremos entender, a menos que haga-mos el esfuerzo de intentarlo y reconocer el enigma de la realidad de lo irreal y de la irrealidad de lo real, tal como los sueños parecen querer demostrar.

39

The House and the LabyrinthMenene Gras BalaguerCurator of the project

The house and the labyrinth is a statement that indicates, or assumes, the exis-tence of a house located in a labyrinth, without specifying which house it is or in which labyrinth it is located. This potential indeterminacy is the one that intro-duces the possibility of a happening, and the construction of a fact of language. A fact of language whose sensitive representation takes the shape of an ope-ning to the world, acknowledgment not a necessary requirement to approach it. Facts of language may or may not correspond with a reality dictated by the senses, as it is more important to understand how words are organized and the structure of the sentence, as well as detecting the meaning of each of the elements, which come together into a new existence whose perception belongs to the realm of imagination. The artist, in this case, identifies herself with the speaker, as a relational subject which sets the world alight through language. It is in this lightning up, in this enlightening, that the units carrying meaning acqui-re the capacity of generating worlds of greater or lesser complexity, which ex-poses the connection between the speaking subject and the language, and how the one cannot exist without the other, who organizes its elements in order to produce the relation between the word and the thing, through the linguistic sign.

House and labyrinth, associated by an article and a proposition, stimulate, both in combination and independently, a succession of images in our imagination, just like other associations which characteristically belong to Japanese haiku, rain and autumn, wind and tree, night and nothingness, water and bird, cloud and twilight. The “how” that is not being said is the invisible link that establishes the comparison between distant terms and introduces meaning into them –like the tea leaves, the stones, as the humidity that permeates everything, the death and the flower, the air, the nothingness, the moon or the crab. The possibilities are endless, because the speaker can give birth to unlimited combinations, as becomes evident in the haiku and in poetry in general. Words are like stones that the speaker gives life to, activating them to communicate. Owing to the speaker words transform into sound elements that we get to listen as if they had a life of its own, and through hearing they relate to the rest of senses.

The exhibition that developed into the spatial intervention of Noni Lazaga is an installation proposal for a hostile space, which resists intervention due to its peculiar architecture, whose presence imposes itself as often happens in other art centres and museums designed to display the work of contemporary artists. The artist visited the site several times in order to familiarize herself with it and investigate its spaces and its environment. Undertaking measurements

NONI LAZAGALa Casa del Laberinto

40 COLECCIÓN CEART N 52 CEART COLLECTION

and calculating the distances between walls, doors windows and ceilings were part of this process. Being completely aware of the challenges posed to her performance, she opted for an interventional process that would transform this densely transited space originally conceived as a “inbetween”, taking the role of a cross-platform interchanger between the ground floor and the second floor, into a conceptual construction whose symbolic expression would be ambiguous enough to activate non-conditioned narratives for its interlocutors and tempo-rary inhabitants. The installation resulting of her taking up of the enclosure is preceded by the careful observation of the connections among the invisible points that exist in all spaces, indicating the directional multiplicity of forces that can be registered as a consequence, as a result of these connections. Planning a strategy to make an intervention in the given space was not an easy task. Nonetheless, the artist faced it by adopting the role of the guest that strives to adapt in a given surrounding. The keys to the intervention were adapting and adjusting the drawing to the space, using the line to introduce a sense of temporality into the space, and never forgetting the necessary visual impact for its function to be recognized. The hybrid site that holds her insta-llation is exposed to the ephemeral look of the observer, who inhabits the art-work by entering into it, but never loses sight of surrounding outer environment.

In the aforementioned space for transition, the artist decided to draw another space, as if she sought to recover the margins of this open, undefined con-tainer, to transform them into a specific frame that wins over a, acting also as asymmetries and spatial tensions. In order to get the drawing suspended in the air, she chose to invade the aerial space, the void framed by the impo-sed demarcations of walls, stairs and ceilings, challenging the force of gravity. Everything begins with the drawing and the line, understood as the adding up of dots, equivalent to the indivisible unit they conform, in a direction that ten-ses the distances and tends to avoid curves. The artist stayed for a long time in Japan during the decade of the 90s, where she learned about Japanese calligraphy. The analogy between drawing and calligraphy lies in the fact that drawing and writing have the use of the line in common. Chinese and Japa-nese calligraphies embrace the art of drawing as the foundational element of the beauty in every stroke; Chinese hanzi and Japanese kanji require great precision in the use of the stroke so as to convey they intended meaning. The metaphysical precepts of the traditional culture in each country, and the re-quired techniques for its execution should also be taken into consideration. Japanese calligraphy, or shodo, is understood as the path of writing -writing traces a path through the void, enabling the presence of speech and creating meaning- and has its origins in Chinese calligraphy, which penetrated in Japan via Korea in the fourth century. The artist achieves something that may seem counterintuitive, tracing strokes over the space, giving meaning to it, after ma-king multiple measurements and calculations between invisible points to disco-

41

ver connections that she transforms into binding bridges that the gaze pierces.

As in previous projects, the cult of Japanese culture is present again in Noni Lazaga’s intervention at the CEART. Even if her many other experiences are of enormous complexity, her prolonged stay in Japan constitutes an influence which cannot be obviated. Living in the country, learning the language, learning about the culture of paper and the art of ink, all of these experience resulted in two books, “La Caligrafía japonesa” (Hiperion, 2007) and “Washi. El papel japonés” (Ed Clan, 2da ed, 2014). The affinity of the artist with this culture has impregnated her work from then on, deriving into multiple connections that resemble those she draws on the space, as she traces lines to contain the void and proclaim that it “is there”, that the void is both the origin and the end of the sensible world. Her proposal responds to an overt interest in the aesthetic values of a culture she does not consider to be in the antipodes of the West, but which she believes to be integrated in the way she conceives the world, owing to the existing links between East and West since Ancient times. It is from there as well that her insistence in approaching the relation between art and place, art and happening, is born. This is a theme she has been developing over her work and trajectory through a poetic of the decons-truction of the given that introduces the geometrical abstraction of her spatial figures, as in “To Dream or not to Dream”, a project preceding the one we present here held at the Protea Gallery at San Diego (April-May, 2013) and also at Instituto Cervantes in New Delhi, where the artist took the space as a canvas and the air as matter, in what has been another application of the amplified concept of an expanded drawing, that she continues to reinterpret.

It may be more appropriate to conceptualize her work as calligraphy that ex-tends into space, by which the artist writes in a language of her invention, dis-tancing herself from the conventional signs of any other language. This way, the action is completed in a kind of circularity that leads from calligraphy to drawing and then back to calligraphy again, closing the circle. Drawing the spa-ce would be then calligraphying it, and therefore the action of drawing would be equal to writing. In both cases, it becomes a path from life to death and to life again, a never ending walk. The notion of path belongs to the tradition of Zen Buddhism, a conception of life and cosmos, originated in India and Chi-na, which, from the 12th century on, was introduced to Japan. This path is a “path of liberation” that reinterprets the Tao philosophy and identifies itself with the path of the enlightenment of the human being seeking to reach satori, or awakening, seen as a mystical experience from a Western perspective, through which emptiness is achieved, attaining the source of all the forms of being and nothingness. From its introduction to the country, Zen spread its influence in every aspect of daily life in Japan, so it remains popular even nowadays. It was the religion of the samurai, embraced by the early shogun rulers as well,

NONI LAZAGALa Casa del Laberinto

42 COLECCIÓN CEART N 52 CEART COLLECTION

and its influence extended into all arts from poetry to painting, calligraphy, architecture, handcraft, tea ceremony, ikebana, teaching and monastic life.

This path to liberation is parallel to the process of acquisition of knowledge on the reality of the world, and this is what has enabled its survival over time. Writing on space does not need a support like a sheet of paper, because it has no alphabet, and its gesture is similar to that of the Japanese calligra-pher who pays careful attention to the precision of the stroke and the tracing of the signs of language he is creating. Noni Lazaga’s drawings are spatial and transform any given space into completely different one; in being appro-priated, space becomes territory. She says -”Nothing is what it seems”- and the noticeable proof of this statement that reminds us of the deceptive natu-re of our senses are her aeroflexias, her aerial drawings and her elastic ar-chitectures. Formless forms of air that she has created during the course of her career and which are taken up again in this exhibition as her preferred method of work, activating them again without prejudices to face the endless void before her. Disregarding the conventional canvas to draw on, she designs structures in a semantically charged space, tracing with woolen thread weight-less geometries that the eye invades and inhabits. These are drawings that frame hypothetical planes in space, as if they were composed by elemental hieroglyphs evoking the fragility of unfinished buildings. The network of spatial relationships generated between these lines and their different points of sup-port in walls, ceiling and floor, exert pressure on different areas of the place, exposing it to multiple readings as its extensions defy all conventional limits.

The path is the concept that structures the installation the artist came up with. She used it to take over this uncommon space that, as has been said, looks like an exchanger or distributor, because it is actually a transit area located on the second floor that connects the ground floor to the third floor, and both floors with the offices beyond the hall. Noni Lazaga drew a path that she defined as “passage”, the goal of which is to guide the passer-by from one point to another. By using this concept, she makes a reference to the transient quality of inhabi-ting, and therefore, to the transient quality of living in itself. The path becomes an abstract geometrical construction, through which the visitor can walk as if overcoming a trial. This allows visitors to explore the place, and forces them to accept conditions established in the space to reach the house at the end of the labyrinth. Space is kept as seized by the artist, and it poses questions to the travelers that are not always answered; from the moment someone decides to get into the installation, they understand that they need to walk through to get somewhere else. Comparing the path to a labyrinth implies that the site challenges its conception as a mere space of transit. The figure of the labyrinth is compared here with the web or crossroad that can be found in every cul-ture, often associated to initiation rites involving the overcoming of obstacles

43

by phases so as to reach a centre. This centre epistemologically represents the image of the transformation of man, and the truth of being and existing.

The hermeneutic circle that, according to Heidegger, encompassed the reci-procity between understanding and living, and between text and context, can be found in the path that leads to the dollhouse located by the end of the route, appearing before the speaking subject. The house is the symbol of the dwelling and the habitat, and refers to the original idea of the Heideggerian building, living and thinking. Paradoxically, it is compared to the principle and source of being, the place where the roots of language can be found; when affirming that speech is the house of being, this does not imply that speech does not constitute the foundation of language, on the contrary. Speech is time and the-refore existential, and is identified with existing in the world and being here. The word is revealed as the truth of being, and this is reciprocally revealed in language, which in turn realizes it. The truth of being comes to language, ap-pears through language. In “What is Metaphysics?” Heidegger notes that “The thought, submissive to the voice of Being, looks up the word through which the truth of Being comes to language.” The house is a living symbol that repre-sents a rectangular building with two ropes subject to both sides of adjacent walls and whose inclination suggests the fall, although it will never happen.

It is a dollhouse that the artist has kept since childhood. It has two floors, a roof with a door, stairs leading to the top, and a façade with the windows ope-ned with or without curtains. The location of the house is confronted with the Fuenlabrada urban center located in the neighborhood of CEART. The game of duplications between the dollhouse and the adjoining buildings extends the dialogue between the interior of the Centre and the main street of the town of Fuenlabrada, which is located in the metropolitan area at a distance of 17 Km from the capital city. However, the house is the only figurative artefact that is recognized at first sight and where the eye finds help to interpret the interven-tion that the artist made by introducing meaning into a non-signified space. Conversely understood, signifying the void in a place that should be defined as a non-place. To reach the house, you must circulate through the labyrinth drawn in the air, the imaginary walls of which hint at the representation of the void, to which the artist aspires. A void that in order to be recognized must be represented sensibly, so she draws upon the point and the line as the original unity in drawing, i.e that at which drawing is essentially reduced, its base grade.

If one can speak of the phases of the process through which the artist has rai-sed, conceived and executed the exhibition itself it is because she has resolved its intervention having in mind an itinerary and a route that takes the concept of threshold and passage area: if the access to the exhibition space starts by entering the passageway, everything leads to the house at the end of the path.

NONI LAZAGALa Casa del Laberinto

44 COLECCIÓN CEART N 52 CEART COLLECTION

The return, however, goes in the opposite direction leading to the geometric construction made with red thread, which claims to represent a large room with a blind window painted on the wall. The interpretative potential opens before the visitor, when questioning himself in order to understand the meaning of this pla-ce that keeps referencing to a dwelling that is only active in his presence. The empty room transitorily harbours whoever is introduced therein, fenced only by one side and inviting to be traversed. The imaginary walls are inventions of the anonymous passer-by that associates a closed place with sheltering. The artist wanted the visit to be an experience for a person that comes to contemplate the created architecture. An enlightening experience in which the visitor is invited to take part of the proposal, based on a selective approach that tests observational skills. Hence the extension of the route involving the access to the perception and understanding of this large structure she calls “Uncertainty meter”, and which de-liberately incorporates advancing on the front steps, where she nails at different heights wires that hang from the top and touch the railings on the second floor.

From the other side of the building, the drawing gives shape to a geometric struc-ture, neither painting nor sculpture, opening a relational field closer to architec-ture, covering the wide frontal disclosed for public viewing. It is about extreme architectures that are not inhabited, although necessary in order to speculate limit shapes that transform the way of looking at man-made locations. The line appears as the axis of a spatial happening that seems to draw itself giving sha-pe to a cosmography, resembling imaginary maps like the ones she designs in her fantasy, superposing them onto a lake or a cloudy sky, onto the top of a hill or into the county. Her production in this field is fruitful from the moment the line draws the volume without weight or thickness, as if those were bodies or sensiti-ve forms, whose transparency eliminates an unnecessary dimension for the re-presentation of a being or a being in the world, that the existing disfigures, melts or decomposes. In all of them, emphasis is also as kind of drawing understood as writing of the form but also in the idea of the line as a time event. The ability in which she moves in the air, as equivalent to emptiness by its vagueness, makes drawing a strong instrument as basis of her work, updating the validity of this shaping in the field of contemporary art. A shaping that is not always recogni-zed as such by often being replaced by machine skills in an information society that puts technology media above the transformation of what we know for sure.

The artist builds with threads, knitting the drawing –knitting is an activity that anticipates gender vindication, when the object is contrary to submission and obedience and is about reinventing the status of the female artist using the same elements that have served to dominate or subdue her. The threads she chooses, black, red or white, used as ropes or cables, resemble light trails or unifying bridges between imaginary islands made of points in she detects on walls, ceilings or floors, or just in the atmosphere and nature; joining them to

45

create forms that would not exist otherwise, whatever the similarities with forms of the real world. The references to the system that supports her creations endorse a production that brings up risks in compositions, which apparently un-fold in space, unwilling to resemble each other or adhere to currents or trends. The history of geometrical abstraction from the 20s in the last century helps recognize alternative artistic practices like hers, but that which really contri-butes to its comprehension are the elective affinities of the artist, whose con-nection with the Japanese culture is obvious although not always self-aware with the same intensity. This dimension of her work is not, however, excluding of a wider experience. It is about a travelling life experience through different parts of the world, from Egypt to Japan. It has always been this kind of training journey that portrays her. From the Arab world to Southeast Asia, setting roads in order to go across territories and cultures; her approaches and distances are balanced in an imagination that stores experiences, that remembers and forgets, and whose mobility never ceases. By analogy, it seems as if the travel experience is actually translated into practice through the domain of language and gestural writing, which is her source of expression in spatial interventions.

Back to the beginning of the exhibition route marked by the artist, through the phases or stages of the journey –the passage, the house, the room and the uncertainty meter– the end of the tour takes us to the beginning in virtue of the reflection produced in the mirror strategically set on one of the walls. A mirror that distorts what is reflected on its methacrylate surface, at whose feet there is a red rain of knotted ropes on the floor in a semicircle, forming a mandala, mirror that distorts whose other half is the image reproduced on the glass. Although it seems as if the mirror were a window that separates the inside and the outside, the real and the imaginary, truth and deception. She has deliberately chosen the mirror as a magical device that in reflecting reality is also susceptible to deform it. You look in the mirror and the mirror looks back at you and everything that is behind you or around you and that is given to see by that devolution the mirror does through the trick of reflection.

The image of the mirror has occupied an important place in mythology and has been always food for superstition, as it is clear from the second part of “Alice in Wonderland”, “Through the Looking Glass”, where Alicia wonders what could be at the other side of the mirror and to know it she passes through and finds herself in a room, where she discovers chess pieces and a book of poetry writ-ten backwards, which can only be read by reflecting it in the mirror. Then she leaves the house of the mirror and enters the mirror world, where the first thing she finds is a garden where flowers speak. Jorge Luis Borges spoke about his fear of mirrors during childhood; not understanding the mystery of why that which stands in front of it is doubled reappearing on its surface. Justified or not, the fear of mirrors is expressed in his fable “The Mirror and the Mask”, or

NONI LAZAGALa Casa del Laberinto

46 COLECCIÓN CEART N 52 CEART COLLECTION

in the poem dedicated to them in the volume “La Rosa profunda” (1972-1975) of his complete works, in which he interrogates the mirror and accuses it of having magical powers, as the word, to duplicate and copy all that is placed before its, because “I do not know what face returns my stare as I lean toward the face inside the mirror.” Powers that cause horror, because “when I die, you will copy another / and then another, another, another ...”. Borges often said to be made of time, and that which despaired him was its irreversibility, una-ble to stop it or change it, as his “dead eyes” and the loneliness of blindness.

The knots of red wool pile on the floor forming a pool of blood; knots of conflict inherited unresolved which the mirror deconstructs into a kind of mandala when duplicating it. Purposeful, the artist’s allusions to this figure of speech are not free or randomly chosen; she relates the mandala to a cosmological diagram or sym-bolic representation of the macrocosm and the microcosm, assuming its univer-sality, from the spiritual and ritual character that preserves since the beginning of time. In the almond-shaped circle, where have been placed the exceeding red ropes of the installation, the resulting mandala represents not the universe but a universe in which the artist imagines feels attracted by the magnetism of a cult figure in many traditions, most of cultures, including Christian and Hellenic figures is identified with mandalic figures- especially in the Hindu and Buddhist. The interpretations that have been made in eastern and western variations are endless, but the one that fits artist purposes is the one made by Carl Gustav Jung in “Erinnerungen, Träume, Gedanken” (Memories, Dreams, Reflections. In this work, Jung recounts that every morning he draws in his notebook a small circle, believing to reflect his feelings and thoughts through a mandala that trans-lates his mood or projects certain internal order of his that in being externalized, can be looked at and is open for interpretations. Jung understood that this little drawing helped him interpret his wakeful dreams, because according to him a mandala integrates both the conscious and the unconscious, and the mandala as archetype is anchored in the collective subconscious. If it is considered that this represents the human being and that in interacting with the sensitive figures that identify it allows a connection between the being or the nothingness and the essence of the world, it is also plausible to believe that this figure helps to res-tore the unity of the fragmented subject, by the practice of meditation and close observation of the drawing from the extremes to the center, wherein the energy is condensed and in turn radiated outwards till closing the circle or square.

In fact, the meaning of the mandala is associated to its equivalence with the representation of a world system. A mandala presupposes a center and that which surround it represents its meaning. This center can be the self and that which surrounds it, or the universe, whatever the shape, round, square or oval. If it is the center of the universe, it is structured by what is understood to be or is

47

an order of the world. There are many types of mandalas and these have been reproduced endlessly throughout history and within many cultures -particularly in Hindu and Buddhist cultures- to represent the macrocosm and microcosm. The mandala is for the artist a map of paths leading to the centre of the self, inviting to redo the road, towards the origin of being and the universe. The figure of the mandala evokes a labyrinth, hence the title of the exhibition, whose cen-ter is a dollhouse that is at the bottom, with its back facing the window, showing the buildings of Fuenlabrada’s Main Street, which are well incorporated into the space where the exhibition is held. Everything seems to look at this centre, the image of the mandala that shapes the puddle of red knots, juxtaposed to its other half, which is completed by the mirror. The optical effect caused by the reflec-tion does not question its unity, but rather the contrary, it reaffirms it. The three-dimensionality of this mandala composed of mandalas, or expanded mandala, corresponds to the construction of an imaginary that connects points in space, but also connecting the Being and the not-Being of the world, in an attempt to explore the vacuum that the artist proposes by working with the spatiality and temporality of an inner geography, wherein she places the centre of the world and the universe. Geography of our unconscious maze, a most fitting symbol for our perplexity and place in which we inevitably lose ourselves when trying to get out. In this losing oneself, there is always a need to wander in search of what we think we are and where are we heading, crossing mirrors to go across ourselves and discover a reality written upside down that we won’t achieve to understand, unless by making the effort to endorse the enigma of the reality of the unreal and the unreality of reality as dreams seem to be in need to prove.

NONI LAZAGALa Casa del Laberinto