NOLDE, Richard James • English Renaissance lute practice as reflected in Robert Dowland's Varietie...

-

Upload

gerard-reyne -

Category

Documents

-

view

1.749 -

download

6

description

Transcript of NOLDE, Richard James • English Renaissance lute practice as reflected in Robert Dowland's Varietie...

Richard James NOLDE

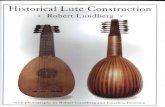

ENGLISH RENAISSANCE LUTE PRACTICE AS REFLECTED IN ROBERT DOWLAND'S VARIETIE OF LUTE-LESSONS A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF MUSIC RICE UNIVERSITY, Houston (May 1984) RICEUNIVERSITY ENGLISHRENAISSANCELUTEPRACTICEASREFLECTEDIN ROBERTDOWLAND'SVARIETIEOFLUTE-LESSONS py RICHARDJAMESNOLDE A THESISSUBMITTED INPARTIALFULFILLMENTOFTHE REQUIREMENTSFORTHEDEGREE MASTEROFMUSIC APPROVED,THESISCOMMITTEE: reyKtan,Prof.ofMusic AnneSchnoebelen,Prof.ofMusic L-__ PaulCooper,Prt':OrlVlusic HOUSTONpTEXAS MAY,1984 Copyright RichardJ a m ~ sNolde 1984 EnglishRenaissanceLutePracticeasReflectedin RobertDowland'sVarietieofLute-Lessons by. RichardJamesNolde ABSTRACT TheVarietieofLute-Lessonsisoneofthemostsig-llificantpublicationsfortheRenaissancelutetoappear inEnglandorEurope.Thisthesisdocumentsearly-seven-teenth-centuryEnglishlutepracticethroughadetailed expositionofthetwointroductorytreatisesinthevolume andanan'J.lysisofselectedaspectsoftheforty-twomusical selectionsthatconstitutetheremainderofthework.The internationalstyleofluteplayingthatdevelopedduring thesecondhalfofthesixteenthcenturyandthestylebrise, whichoriginatedinFranceduringthefirstyearsofthe seventeenthcentury,arebothreflectedinthecollection. OnthebasisofthematerialsintheVarietieofLute-Lessons andextensivereferencestosixteenth- andseventeenth-centurysourcesofmusicfortheluteandrelatedinstruments; thefollowingtopicsarediscussed:Renaissancelutetech-nique;therelationshipbetweenlutetechniqueandcomposi-tionalstyles;proceduresforfretting,stringing,andtuning thelute;pedagogicalapproachestolutetechnique;and contemporaryperformancepractices.Backgroundinformation ontheoftheVarietieofLute-Lessonsandthe rolesofJohnandRobertDowlandinitsproductionhasalso beenincluded. TABLEOFCONTENTS Page LISTOFTABLES LISTOFFIGURES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .o Chapter 1.INTRODUCTION..................1 II.HISTORICALBACKGROUNDOFTHEVARIETIEOFLUTE-LESSONS..9 AnOverviewofEnglishLuteMusic11 ThePublicationofLuteMusicinEngland15 ReferencestoaPublicationContainingJohn DowlandsLuteMusicand/orHisTreatise onLute-Playing...23 RobertDowland'sRoleintheProductionof theVarietieofLute-Lessons...31 III.SELECTEDDIDACTICWORKSFORTHERENAISSANCELUTE55 . . . . . . 55 ContinentalLuteBooks EnglishLuteBooks.. . . . ..59 IV.THENOTATIONOFRENAISSANCELUTEMUSIC PitchRepresentation. . . RhythmicElements. . . . 79 80 .86 OtherSymbolsinLuteTablatureo0DOD96 V."NECESSARIEOBSERVATIONSBELONGINGTOTHELVTE, ANDLVTEPLAYING,"BYJOHNBAPTISTOBESARDO OFVISONTI..98 PedagogicalAspectsofBesard'sTreatise.99 IndividualElementsofLuteTechnique.116 HoldingtheLute116 Left-handPosition. . . . . . . . .118 iv Page . . . . . ,119Left-handFingerings Single-stops ShiftsofPosition ..122 .125 BarreTechnique. .. . . . . . . . . 129 MultipleStops. . . . . 131 SustainedTones. . . . . .,. . . . 144 RightehandPosition . . . . 145 FingeringofSingleStops152 Right-handFingeringofMultipleStops162 Right-handFingeringofPassagesinTriple rileter.170 TextualVariationsinDifferentEditionsof Besard'sTreatise.............. 175 SelectedSeventeenth-CenturyDescriptionsof Right-handUsage185 SelectedElementsofVihuelaTechnique191 ReasonsfortheDevelopmentoftheThumb-over ApproachtoRight-handTechnique194 GuidelinesforModernPlayers:Adoptingan ApproachtoRight-handTechnique 200 VI."OTHERNECESSARYOBSERUATIONSBEI;ONGINGTOTHE LVTE,"BYIOHNDOVLAND,BATCHELEROFMUSICKE205 "ForChusingofLute-strings". . . . . . . 205 DeterminingtheQualityofLuteStrings205 SourcesofLuteStrings. . . . ... . . 217 "OftheRightSizesofStringesvpon theLute 221 StringingtheLute.. . . . . . 221 OctaveversusUnisonStringingoftheBass CoursesoftheLute 226 VII. VIII. v Page SingleversusDoubleStringingofthe TrebleCourseoftheLute 230 234 246 AdditionalBassCoursesontheLute tlOfFrettingtheLute" ... . . DevelopmentoftheFingerboard . . . . 248 LocatingtheFretsontheFingerboardof theLute257 OtherSystemsforFrettingtheLute . . 272 FurtherAdjustmentsoftheFretPositions279 FasteningtheFretstotheNeckoftheLute286 tI OfTuningtheLute II. . . . . . . 289 Lut aPitch . . . 289 ProceduresforTuningtheLute . . . . 305 PRACTICES "e" ". . . . . 318 Ornamentation0 320 GracesofPlay . . 323 Divisions... . . . . . . InterpretativePerformancePractices 370 422 . . ContrastingDynamics ContrastingTimbres o" . Articulations . . . . . Tempo. . .. . . . CONCLUSIONS. . . . ". . . . . . 422 425 . . D 427 . . 435 449 BIBLIOGRAPHY . . . . . . . . 456 Table 1. 2. 3. LISTOFTABLES PrintingHistoryofSelectedEnglish MusicBooks.1596-1612. MusicalSelectionsintheVarietieof Lute-Lessons SelectedSixteenth-CenturyDida.t:.:tic WorksfortheLute 0 . . Page 20 40 57 4.ContentsoftheVarietieofLute-Lessons76 5 CommonConfigurationsofBassCourses ontheRenaissanceLute241 6.ConfigurationsofBassCoursesforIndividual CompositionsintheVarietieofLute-Lessons243 7.SummaryofConfigurationsofBassCourses UtilizedintheVarietieofLute-Lessons245 8.FretPositionsAccordingtoDowlandandGerle265 9.IntervalRatiosProducedbySelected TuningSystemsandTemperaments.267 10.UsablePitchRangesofil'iodernGutStrings304 11.ThomasRobinson'sFallsandRelishes fromTheSchooleofi'iiusicke347 12.RhythmicComplexityofDivisionsin CompositionsintheVarietieofLute-Lessons396 13.DistributionofDivisionswithinCompositions intheVarietieofLute-Lessons.400 LISTOFFIGURES FigurePage Title-pageoftheVarietieofLute-Lessons. .21 2.DedicationoftheVarietieofLute-Lessons32 3 4. Introductoryaddressandpoemof oftheVarietieofLute-Lessons Headnotetothetreatiseonfingering byJean-BaptisteBesard . . . . .34 . . . . . 36 5."SirThomasMonson'sPavan"byRobertDowland fromtheVarietieofLute-Lessons,transcribed forkeyboardbyEdgarHunt,SChott'sSeriesof EarlyLuteMusic,no.1(London:SchottandCo., 1957),pp.26-8..45 6."Almande"byRo:Dow1andefromthe BoardLuteBook,fol.12v48 Title-pageofA NewBookeofTabliture.. .64 8.FirstpageofJohnDowland'ssettingof"Fortune" asitappearsintheBritishLibrarycopyofa NewBookeofTab1iture,she1fmark:K.1,c.1867 9 Title-pageofTheSchoo1eofI\',usicke..70 10.Italianlutetablature."Recercare"byFrancesco SpinacinofromIntabo1aturadiLauto.Libra Primo.(Venice,1507)...81 11.Frenchlutetablature."PaduanaI"byPierre Pha1esefromLiberIIII.Carminumpro Testudine..(Louvain,1546). 82 12.Germanlutetablature."DerZieglerinBerhecken" byHansNewsid1erfromEinnewesLauttenbuchlein (Nuremberg,1540).........83 13."TheEarleofDarby'sGal1iard"byJohnDowland, fromtheVarietieofLute-Lessons,sig.94 14.Selectedwingering fortheLeftHand fromHansJudenkunig'sAinSchoneKur.stliche Underweisung.......120 Figure 15 A GalliardbyThomasRobinsonfrom TheSchooleofi'iiusicke,sig.D2v viii Page . . - . .171 16.n!'IIistrisWintersJumpe,"byJohnfrom"AnInstrvctiontotheOrpharion,' inA NewBookeofTabliture,sig.Dr... 174 17.IllustrationsofFingeringRulesbyJean-BaptisteBesar.d,"DeModoinTestvdine StvdendiLibellvs,"intheThesaurus Harmonicus(Cologne.1603),sigs.Xxr-Xx4r. 177 18.Illustrationofala-courseLuteandan11-courseTheorbobyr{laI'inNiersenne,fromhis HarmonieUniverselle:TheBooksonInstruments, translatedbyRogerE.Chapman,1957,p.74.233 19.Title-pageofWilliamBarley's"AnInstrvcti,on totheOrpharion."inA NewBookeofTabliture, [sig.A3r J............239 20.KnotusedforAttachingLuteStringstothe Bridge,Above,TopView;Below,SideView281 21.JohnDowland'sTableofPitchesoftheHexachord SystemandtheirRelationtoPositionsonthe FingerboardoftheLute,fromtheMargaret BoardLuteBook,facingfol.lr..295 22.ThomasRobinson'ssettingsof"0Lordthatart myRightenousnesse, "fromTheSchooleof iviusicke,sopranopart,sig.N2r;basspart, 23. 24. 25. sig.Ov;completesetting,sig.02v.298 IntervalsbetweentheOpenCoursesoftheLute, fromJohnDowland's"OtherNecessaryObser-uationsBelongingtotheLvte,"inVarietie ofLute-Lessons,sig.E2r. 311 "TheEarlofDerbY'sGalliard,"byJohnDowland, fromtheSampsonLuteBook,fol.13v. 340 GracesofPlayfromThomasMace' sMusick's Monument(London,1676),pp.102-110. . . 352 26."UndouxNennin,"byOrlandodeLassus,embel-ishedandintabulatedforlutebyAdrianLeRoy, inA briefeandplaineInstructiontosetall MusickeofeithtdiuerstunesinTableturefor theLute,fols.35v-37..... 388 ix FigurePage 27.Coranto#3.byananonymouscomposer, fromtheVarietieofLute-Lessons,sig.C2r.402 28."SirJohnLangton'sPavan,"byJohnDowland, fromtheVarietieofLute-Lessons, sigs.Kv-K2v... ..404 29 . Volt#3,byananonymouscomposer,from theVarietieofLute-Lessons.sig.Sr 30.Pavan#1,byMaurice.LandgraveofHesse, fromtheVarietieofLute-Lessons, .407 sigs.H2v-Ir.....408 31.Pavan#4,byDanielBacheler,from theVarietieofLute-Lessons,sigs.I2v-Kr414 32.Pavan#6,byAlfonsoFerreboscoofBologna, fromtheVarietieofLute-Lessons, sigs.K2v-Lr..417 33 Volt#4,by[?Gaultier].from theVarietieofLute-Lessons,sig.Sv. . . .420 34."NiyLadyHunsdonsAllmande,"byJohnDowland, fromtheDowlandLuteBook.FolgerLibrary: MSV.b.280(formerlyMS1610.1),fol.22v433 35.TwotablesbyAndreasOrnithoparchusshowing therelativevaluesofeachkindofnote accordingtoavarietyofmensurations proportions,fromAndreasOrnithoparcusHis Micrologus,orIntroduction:Cont.a.iningthe ArtofSingingbyJornnsigs.OvandPv. 441 "TheWitchesdaunceintheQueenesMaske," by[RobertJohnson],fromtheVarietieof Lute-Lessons,sig.P2v........ 445 I.INTRODUCTION RobertDowland'sVarietieofLute-Lessonsisthelast andmostimportantcollectionofmusicfortheRenaissance lutetobepublishedinEngland.Thework,whichis comparabletothefinestEuropeanpUblicationsforthelute, appearedin1610whentheclassicalperiodofEnglishlute musicwasdrawingtoaclose.TheVarietieofLute-Lessons containstwodidactic,introductorytreatisesbyJean-BaptisteBesardandJohnDowlandrespectively.Besard's treatisedealsprimarilywithlutetechnique,whileDowland's concernsstringing,fretting,andtuningthelute.The treatisesarefollowedbyforty-twomusicalselectionsin lutetablaturethatarearrangedbygenreinthefollowing sixgroups:Fantasies,Pauins,Galliards,Almaines,Corantoes, andVoltes.Theseselectionsdemonstratetheinternational characteroftheluterepertoireattheendofthesixteenth centuryandthedistinctivefeaturesoftheItalian,French, andEnglishstylesofcomposition. InspiteofthesignificanceoftheVarietieofLute-Lessons,nocriticaleditionorcomprehensivestudyofthe workasawholeexists.Besard'streatisehasbeenexamined inseveralrelatedstudiesbyJuliaSutton,JosephGarton, 1 2 andMarcSouthard,landitisavailableinamodernfacsimile editiondevotedtoBesard'sinstructionsforplayingthe lute.2 TheonlystudyspecificallyconcernedwithDowland's treatiseisalate-nineteenth-centurycommentarybyWillibald NagelthataccompanieshisGermantranslationofDowland's material. 3Thefirstmoderneditionoftheentiregroupof musicalselectionsintheVarietieofLute-LessonsisEdgar Hunt'ssetofkeyboardtranscriptionswhichappearedin1957.4 Althoughthetwointroductorytreatisesarenotincludedin hisedition,Hunthasprovidedbriefbiographicalnoteson someofthecomposersanddedicateesrepresentedinthework. Unfortunately,eventhoughHuntcorrectedmanyoftheprinting errorsthatappearedintheoriginaledition,heintroduced newerrors.Thiseditioncontainsnodocumentationofthe originalerrataorof "Hunt'seditorialemendations.Several IJuliaSutton,"Jean-BaptisteBesard ISNovusPartusof 1617"(Doctoraldissertation,EastmanSchoolofMusic,1962), andotherderivativeworks;JosephGarton,"Jean-Baptiste Besard'sThesaurusHarmonicus"(Doctoraldissertation,Indiana Univers it, ,1952);andMarcSouthard,"Sixteenth-CenturyLute Technique'(Master'sthesis,UniversityofIowa,1976). 2JeRn-BaptisteBesard,JeanBaptisteBesardus:Instruc-tionenfurLaute1610und161,lViiteinemNachwortVersehen vonPeterPaffgenNeussRhein:InstitutioproArteTestudinis, 1974) 3WillibaldNagel,"JohnDowland'sNecessarieObservations belongingtoLute-playing,"iVIonatsheftefUrfviusikgeschichte23 (1891):145-62. 4RobertDowland,VarietieofLute-Lessons,Lutetablature transcribedforkeyboardbyEdgarHunt,SChott'sSeriesof EarlyLuteMusic,no.1(London:SchottandCo.p1957). 3 otherfaultsmakethiseditiondifficulttouse.Hunt doesnotindicatetherelationshipofthetranscribednote valuestothenotevaluesimpliedbytheoriginaltablature. ThisisproblematicbecauseHuntisnotconsistentinhischoice ofnotevalues.Thephysicallayoutofthemusicinthis editionfrequentlyrequirespageturnswithinapiece,and thespacingofthestavesmakessomepiecesdifficultto follow.Voice-leading,whichiscapriciousatbestinlute music,isoftenunclearandinconsistentinthetranscrip-tions.Forexample,agivensequenceofnotesinthetablature maybetranscribedastwocontrapuntallinesinitsfirst appearance,onlytoberecastasasingle,wide-rangingline whenthesamematerialreappearslaterinthecomposition. Finally,thekeyboardtranscriptionsdonotaccuratelyconvey thesoundofthemusicasitwouldberealizedonthelute. In1958,Huntpublishedafacsimileeditionofthe VarietieofLute-Lessons.S Thiseditioncontainsallofthe 'RobertDowland,VarietieofLute-Lessons,A litho-graphicfacsimileoftheoriginaleditionof1610,withan Introduction,andaNoteontheLuteandLuteTablatureby EdgarHunt(London:SchottandCo.,19,8).Thiseditionis basedontheBritishLibrary'scopyoftheoriginalprint, whichbearstheshelfmark,K.2.i.8.Othercopiesofthe originalprintarelocatedintheBodleianLibrary;theHenry E.HuntingtonLibrary,SanMarino,California;theLibraryof Congress;andtheprivatelibraryofPrinceLorrach-Baden,Germany.JohnWardidentifiesthecopyinthe LibraryofCongressastheJamesE.Matthewscopy,in"ADow-landMiscellany,"AppendixW.MiscellaneousNotesonthe PrintedSources,JournaloftheLuteSocietyofAmerica10 (1977):144.Thelocationsoftheothercopiesaregivenby DianaPoultoninJohnDowland:HisLifeandWorks(Berkeley andLosAngeles:UniversityofCaliforniaPress,1972),p.479. 4 materialoftheoriginalprint,abriefnoteontheluteand lutetablature,andthebiographicalnotesofHunt'sprevious edition.Thenewinformationisincompleteandinaccurateat severalpoints,andagainthereisnolistoferrata.Hunt's failuretoindicatethetuningofthebasscoursesofthe luteforeachpieceisparticularlylamentablebecausehis descriptionoftheapplicableoptionsiserroneous.Thereis nodescriptionofcontemporaryperformancepracticesorlist ofconcordancestoassisttheperformerorscholarindealing withpassagesofquestionableaccuracy. Hunt'seditionsoftheVarietieofLute-Lessonsremained theonlyonesavailableuntilJohnDuarteandDianaPoulton publishedaseriesofvolumesdevotedtoguitartranscriptions ofthemusicalselectionsduringthe1970s.6 Thesetranscrip-tionsarenotfaithfulrealizationsofthelutetablature forseveralreasons,themostimportantofwhichisthatthe rangeoftheguitarcorrespondstotherangeofthehighest sixcoursesofthelute.Anynotesthatlieonthelute's lowestbasscoursesmustbeomittedortransposedupan octave.Becausethetuningofthelute'shighestsixcourses differsslightlyfromthetuningoftheguitar,certainchord-voicingscannotbetransferredtotheguitarwithoutmodifying themoromittingoneormoretones.JohnDuartedescribesthe 6RobertDowland,VarietieofLute-Lessons(1610),tran-scribedfortheguitarbyJohnW.DuarteandDianaPoulton, 6vols.(AnconaandMilan:EdizioniBerben,1971-76). editorialpolicyofthiseditionasfollows: Virtuallynothinghasbeenomittedfromthe original(savetheerrors)andwhereithasbeen necessarytochangetheoctaveinwhichanoteor passageappears,itiswithoutharmtothesense 'ofthemusic.Sinceguitarmusicisalready heavilyburdenedwithcaballisticsymbols,... Idecidednottoaddtothetaskoftheuserby indications[sic]ofeditorialchangesintext.7 Becausecorrectionsandalterationsarenotdocumentedin thetextorinaRevisionsbericht,thescholarlyvalueof thiseditionislimited.ThisisunfortunatesinceDiana Poultonisoneoftheworld'sleadingauthoritiesonJohn DowlandandEnglishlutemusic.Whileshehascontributed biographicalnotesandintroductorycommentstothisedition, herscholarlyacumenislostinthelackofdocumentation thatpervadesthisedition.Duarte8sbriefcommentson performancepracticesandtheeditors'successinmakingthe transcriptionsactuallysuggestthesoundsofaperformance onthelutearethestrongpointsofthisedition.Guitar-istswillfindthatmodernapproachestofingeringthe musicforthelefthandhavebeenutilizedinaneffortto makethemusicaccessibletomoreplayers.Thiseditionmust be aperformingeditionratherthana scholarlyworkintendedformusicologistsandlutenists. A numberofindividualcompositionsfromtheVarietieof Lute-Lessonshaveappearedinmodernanthologies,eitherin 7Ibid.,Forewordtoeachofthesixvolumes,p.5. 6 lutetablatureorintranscriptionsforguitar,butnoother comprehensiveeditionofthemusicalselectionsexists.This issurprisingsinceHunt'sfacsimileeditionhasbeenwidely availableforovertwenty-fiveyears.andagreatdealof researchonEnglishlutemusichasbeendonesinceitspub-lication. InlightoftheimportanceoftheVarietieofLute-Lessonsandtheshortcomingsoftheexistingeditions,yet another,criticaleditionofthevolumeisentirelyjustified. Thisthesiswasoriginallyconceivedasavehicleforthe productionofsuchawork.but,asworkproceeded,itbecame clearthatextensiveresearchintoanumberofaspectsof Renaissancelutepracticewasnecessarytoensuretheinteg-rityandcompletenessofthefinalproduct.Investigationof thefollowingtopicswasdeemednecessaryforacomprehensive evaluationanddiscussionofthematerialsintheVarietieof Lute-Lessons:thenotationoflutemusic,Renaissancelute technique,pedagogicalapproachestolutetechnique,didactic worksforthelute,improvisedornamentation,divisiontech-nique,contemporaryperformancepractices,therolesofJohn DowlandandRobertDowlandintheproductionoftheprint, sourcesofEnglishlutemusic,thedevelopmentofsystemsfor printinglutetablature,thedevelopmentofthelute,the propertiesofgutstrings,pitchinsixteenth- andseventeen-centurylutemusic,temperamentsusedonfrettedRenaissance stringedinstruments,Renaissancecompositionaltechniquesand 7 theoreticalperspectives,idiomaticelementsoflutemusic, thedistributionofspecificgenresintheluterepertoire, earlyBaroquelutepractice,andforeigninfluenceson Englishlutepractice.Informationontheseitemsisfound inmanydiversesourcesthatvaryconsiderablyinreliability andaccessibility.Inmanycases,recentresearchhas provenearlyinvestigationsinthefieldoflutemusicto beinaccurateormisleading.Thus,asecondarypurposeof thisthesisbecamethecompilation,verification,and documentationofexistingsourcematerialsintheseareas tomaketheinformationmorereadilyavailabletolutenists andmusicologists.A single,well-organizedpresentationof thisinformationprovidesasolidfoundationforthestudy ofRenaissancelutemusicintheVarietieofLute-Lessons andinothercollectionsaswell.Oncethesetopicshad beenresearchedandtheinformationcompiled,itwasdecided thatthescopeofthethesisshouldberedefinedinlightof thetremendousvolumeofmaterialthathadbeenassembled. Asaresult,thecriticaleditionofthemusicalselections inthecollectionhasbeendeferreduntiltimeandcircum-stancespermitfurtherst.udy.Althoughthecompositionsare notdiscussedingreatdetailinthisthesis,considerable studyofthemusicwasrequiredtocompletethethesisits presentformandtopreparefortheeventualrealizationof thecriticaledition.Similarly,whilesecondarysources provideasUbstantialpartoftheinformationinthethesis, theauthor'soriginalresearchandanalyticalcomparisons ofdifferentsourcesprovidenewinsightsintomanyofthe topicsdiscussed.Theauthoracknowledgesasignificant. debttoearlierresearchersinthefieldofEnglishlute music,particularlyDavidLumsden,DianaPoulton,andJohn Ward.Thewritingofthisthesiswouldhavebeenimpossible withoutthebenefitsoftheirstudy.Thenumerouscitations totheirworksthatappearinthisthesiscanonlybeginto indicatethescopeoftheirknowledgeofavarietyofsub-jectsthatareexaminedinthethesis. 8 II.HISTORICALBACKGROUNDOFTHEVARIETIEOFLUTE-LESSONS ChangesthatoccurredinSnglishsocialandcultural institutionsduringthesixteenthcenturycreatedagrowing demandforsecularmusic.WhenKingHenryVIIIfoundedthe ChurchofEnglandin1534,heconfiscatedtheholdingsof monasteriesrunbytheRomanCatholicChurchanddistributed themamonghisfavoritecourtiers.Onedirectconsequence ofthisactwastherelocationofmanymusicianswhohad servedinecclesiasticalpositions.Insomecases,these displacedmusiciansfoundemploymentinmusicalestablish-mentscreatedbythenewownersorbeneficiariesofthe propertiesformerlyheldbythemonasteries.Inothercases, themusiciansobtainedpositionsinmusicalestablishments createdbymerchantswhomadefortunesinthewooltrade withFlanders. Whileinthefifteenthcenturymusicalestablishments wereafeatureofonlytheverylargestcountrycastles andmansions,bytheendofElizabeth'sreigneventhe smallerhouseshavetheirmusicbooks,theirinstruments, theirdistinguishedresidentmusiciansandcomposers, andtheirvisitingminstrels.l IThurstonDart,ForewordtoAPlaineandEasieIntrodvc-tiontoPracticallMvsickebyThomasMorley(London,1597), modernreprinteditionbasedonthesecondeditionof1608, ed.byR.AlecHarman(NewYork:W.W.Norton,1963;The NortonLibrary,1973),p.ix. 9 10 Asthedemandforsecularmusicgrew,thestudyofmusic becameapartoftheeducationofyoungboysatbetterschools. .AtDulwich,Westmininster,Christ' sHospital,IiJerchant Taylor'sandevenatafewlocalgrammarschools,music waspartofthecurriculum.Thepage,theapprentice, andtheschoolboywereexpectedtobeabletosingand2 playsomeinstrumentorother,notnecessarilyverywell. TheuniversitiesatCambridgeandOxfordofferedmoreadvanced instructioninmusicforstudentswhowishedtopursuea careerinmusic.Althoughthemajorityofyoungboyswhore-ceivedelementarytraininginmusicdidnotbecomeprofession-almusicians,theirearlyacquaintancewithmusicstimulated thegrowthofamateurmusicmakingandcreatedademandfor didacticpublicationsandcollectionsofmusicfortheir instrument s Sometownsinstitutedthepracticeofmaintainingspecial bandsofmusiciansknownasthetownwaitstoprovidemusic forofficialeventsandceremonies.Thesegroupsenjoyedsuch highregardthattheirserviceswereingreatdemandfor privatefunctionsalso.Playhousesfrequentlyemployedbands ofmusicianstoaccompanytheatricalproductions, andtroupes ofEnglishactorsandmusicianstouredEuropefrequentlydur-ingthesecondhalfofthesixteenthcentury.Clearlythen, secularmusicheldanimportantpositioninEnglishsocialand culturalinstitutionsbytheendofthesixteenthcentury. 2Ibid.,p.xi. 11 AnOverviewofEnglishLuteIVlUsic LittleisknownaboutthehistoryoftheluteinEngland duringthefirsthalfofthesixteenthcentury.Whilesome referencestolutenistsatcourtanddescriptionsoflutes ininventories' ofmusicalinstrumentsdatefromtheearly yearsofthecentury,theearliestextantsourcesoflute musicappeartohavebeenwrittenduringthemiddleyearsof thecentury.Thesourcesoflutemusicthatappearedafter thistimedocumentthedevelopmentofanimportantschoolof nativelutenistcomposersduringthesecondhalfofthesix-teenthcenturyandthefirstyearsoftheseventeencentury. Theclass.icalperiod,.orGoldenAge,ofEnglishlutemusic extendedfromapproximately1590to1615,withitspeak occurringattheturnofthecentury.Althoughitwasstill playedaslateas1640,theRenaissancelutedeclinedin popularityinEnglandafter1615.ThedateofJohnDowland's death,1626,isoftencitedastheterminaldateforthe significantactivitiesofthenativeschooloflutenistsin England. IntheearlyyearsoftheRenaissance,Englandlagged behindthecountriesofEuropeinproducingmajorcomposers ofmusicfortheluteandperformersofinternationalrenown. ItwasnotuntilthereignofQueenElizabeththattheEnglish schooloflutenistsgainedparityinthisregard.JohnDowland wasprobablythemostfamouslutenistofhisday,andhisworks werepublished,copied,imitated,andperformedthroughout EnglandandEurope.Hisworksarefoundinthesourcesof lutemusicmorefrequentlythanthewoorksofanyother composer. 3AlthoughmostEnglishcomposersforthelute werenotinnovators.theirabilitytoassimilatethe compositionalstylesandtechniquesoftheirContinental counterpartsandtheirnativefacilityincreatingtuneful 12 melodiesallowedthemtocomposeworksofoutstandingexpres-sivityandbeauty.Asawhole,Englishlutemusicismore notableforitsmelodicgracefulnessthanitstechnical sophistication. Thenearlythreethousandpiecesinthe~ n g l i s hrep-ertoireforRenaissancelutearedistributedamongalmost fiftymanuscriptsandprintedbooks.Thisrepertoire,which isnearlyfourtimesaslargeasthevirginalrepertoireof thesameperiodinEngland,testifiestotheprominent positionoftheluteinthemusicalworldofitsday.There isasmallgroupofapproximatelyonehundredtoonehundred andthirtypiecesthatappearwithmuchgreaterfrequencythan therestoftheotherpiecesintherepertoire,whichsuggests thattheseworkswerethemostpopularonesoftheperiod. Manuscriptcollectionsoflutemusicdocumenttheperson-altasteand/orprofessionaldevelopmentofthestudents, 3AnthonyRooley,"JohnDowlandandEnglishLuter,iusic," EarlyMusic3,no.2(April,1975):115 13 teachers,performers,andprofessionalscribesthatcompiled them.Whilesomemanuscriptswereproducedbyasingle copyist,manyofthemcontainthecontributionsofseveral peopleduringalongperiodoftime.Thus,manuscripts demonstrateavarietyofapproachestotheliterature. Ontheotherhand,printedlutebooksfurnishsome indicationofthemusicaltasteofthelute-playingpublic atthetimeofpublication.Forexample,inhiscollection oflutemusicthatwaspublishedbyPetrucciin1508,the Italianlutenist,JoanambrosioDalza,apologizesforincluding somanyeasypiecesinthework.Hestatesthatthepublic demandsthembecausenovicesandamateurscannotplaythe moredifficultpiecesthathewouldliketopublish.4 The commercialsuccessofaprintedlutebookdependedtosome . extentonthepublisher'sabilitytosensecontemporary musicalfashionsandtopresentworksthatwouldappealto awidefollowing.Printedcollectionsoflutemusicusually containmusicofprovenpopularitythatrepresentsthe cUlminationofmusicaltrendsratherthannewdevelopments.5 Printedlutebooksfrequentlyprovidebibliographic informationaboutcompositionsthatisusuallyabsentin 4DanielHe art z,"LesPremieres'Instructions'PourIe Luth;Jusquevers1550,"LeLuthetsaIviusigue,ed.Jean Jacquot(Paris: . CentreNationaldelaRechercheScientifique, 1958),p.77 5DavidLumsden,"TheSourcesofEnglishLutei'ilUsic(1540-1620)"(Doctoraldissertation,CambridgeUniversity,1955), p.24. manuscripts.Whileindividualworksarerarelydatedin manuscriptsorprintedbooks,theinclusionofapiecein aprintedbookestablishedthelatestdatebywhichthat piecemusthavebeencomposed.Selectionsinprintedbooks aregenerallytitled,whereaspiecesinmanuscriptsare 14 frequentlyuntitled.Surprisingly,thenameofthecomposer orarrangerofapieceisoftenomitted,abbreviated,or reducedtoinitialsinmanuscriptsandinprintedbooks. Manypiecesintheluterepertoireremainunidentifiedeven afterextensivecomparisonofthesepiecestocontemporary worksinthevocalandvirginalrepertoires. Somescholarsfeelthataprintedversionofacom-positionshouldbelook.eduponasanauthoritativetext becausetheprintingprocessrequiresgreatattentiontothe detailsofthetablatureinpreparingtheprintingplates. However,thestandardofaccuracyrealizedintheprinted lutebooksisnotsignificantlybetterthanthatofmost manuscripts.Unauthorizedandposthumouspublicationof workswascommonduringthisperiodinEngland.Forexample, intheprefacetohisFirstBookeofSongsorAyres,John '" Dowlandcomplainedthattherewereerrorsinseveralofhis piecespublishedbyWilliamBarleyinANewBookeofTabliture withoutDowland'spermission.Yet,theVarietieofLute-1 ~ s s o n s ,publishedbyDowlandandhissonRobert,isnot withoutitsownerrors,andsomeofthecomposersrepresented hadbeendeadforseveralyearswhentheprintappearedin1610. 15 ThePublicationofLuteMusicinEngland LessthantenpercentofthepiecesintheEnglishlute repertoirearefoundinprintedbookswhilenearlyallofthe vocalmusicoftheperiodappearedinprintedcollections.6 Ithasbeensuggestedthatthis.discrepancymayindicatea distinctionthatpublishersmadebetweenmusicthatwouldhave appealedtoalargeamateurfollowingandmusicthatwould havebeenofinteresttoamorelimitedclientele.However, entriesintheLondonPortBoo.ksfor1567/8indicatethatthe lutehadasubstantialfollowinginEnglandwellbeforethe endofthecentury.Duringoneten-monthperiod,eighty-six lutesand13,848lutestringswereimportedfromvarious citiesinEurope.Furthermore, Soimportantwasthecommerceinlutesthattheyare amongthesmallnumberofmusicalinstrumentslisted inTheRatesoftheCustomeshouse,printedinLondon, 1582,fortheuseofthosewhosejobitwastocollect dutyonimports.7 ItisclearthatthereweremanylutenistsinEnglandat thistimeandthattherewasademandforlutemusic.This demandappearstohavebeenmetthroughthecopyingof manuscriptsandthepublicationofprintedbooksinEngland, andtheimportationofworksforthelutefromtheContinent. 6Ibid.,p.16. 7JohnWard,"ADowlandMiscellany,"AppendixL." . to bestowesomeydolltymeupponthelute. ,"Journalofthe LuteSocietyofAmerica10(1977):116-17. TheFrenchAdrianLeRoy,issuedtutorsforthe lute,guitar,cittern,andmandoreduringthemiddleyears ofthesixteenthcentury,andseveraloftheseworkssub-sequentlyappearedinEnglandintranslation.8 Itis possiblethatEnglishpublishershadlittledesireto 16 competewithestablishedContinentalpublishersofmusic becauseofthelargeinitialinvestmentinspecialelements ofprintingtyperequired.Alternately,theymayhave beenunabletoobtainanadequatestockoftheseelements beforethefinalyearsofthecentury.InEngland,"Itwas notuntilthelastdecadeofthesixteenthcenturythatmusic printingappearedinsimilarquantityandqualitytothatof theContinent. ,,9Thisdelaymayhavebeendueinparttoa numberofrestrictionsthatgovernedtheactivitiesofpub-lishersandprintersinEngland. AnassociationofmenknownastheStationer'sCompany ofLondoncontrollednearlyeveryaspectoftheprinting businessandbooksel1ingtradeinEngland.Thisorganization 8See"L'OeuvrePedagogiqueD'AdrianLeRo:Y,,"inAdrian LeRoy,LesInstructionsPourleLuth(1574)"'Corpusdes LuthistsFrancais:OeuvresD'AdrianLeRoy,'(Paris:Bditions du.CentreNationaldelaRechercheScientifique,1977),vol.1: IntroductionettextedesInstructions,ed.byJeanJacquot p Pierre-YvesSordes,andJean-MichelVaccaro,pp.XXIII-XXIV foradiscussionoftheseworks. 9WilburnNewcomb,LuteMusicofShakespeare'sTime: WilliamBarley,A newBookeofTab1iture,(1596),editedand transcribedforkeyboardwiththeOriginalTablature(Univer-sityPark:ThePennsylvaniaStateUniversityPress,1966), p.xi. 17 receivedaroyalmonopolyfromQueenElizabethin1586that preventedanyonefromenteringthetradewithoutitsconsent. However,theprintingofmusicbooksandrelateditemswas exemptfromtherestrictionsofthismonopolybecausemusic printingwasregulatedbyprivatepatentspreviouslygranted. Thesemusicpatentsincludedapatentthatwasgrantedto WilliamByrdandThomasTallisin1575fortheprintingof allmusicbooksexceptcollectionsofmetricalpsalmtunes. Thisprivilegewasextendedtothemforaperiodoftwenty-oneyears,i.e.,until1596,butneitherByrdnorTallishad adequatetimetodevotetotheprintingbusinessandfew workswerepublishedundertheirpatent.WhenTallisdied in1585.ByrddesignatedThomasEastashisassigneetoprint musicbooksforhim.TheindustriousEastseizedthecoveted opportunityandproducedmorenewmusicbooksduringthesix-yearperiodendingin1593thanhadbeenproducedinthe eightyyearsprecedinghisappointmentasByrd'sassignee.10 AfterByrd'spatentexpiredin1596,severalLondonprinters enteredthemarketinaburstofunregulatedmusicprinting. 'l'heseincludedPeterShort,whoprintedDowland'sFirstBooke ofSongesorAyresin1597,andWilliamBarley,whobecame ThomasMorley'sassigneewhenMorleyreceivedthemusicpat-entin1598.BarleypublishedANewBackeofTablitureand lODart,ForewordtoA PlaineandEasieIntrodvctionto PracticallMvsickebyThomasMorley,p.xi. ThePathwaytoMusickeindependentlyin1596,and[vlorley's TheFirstBookofConsortLessonsasMorley'sassigneein 18 1599.Theexpansionofmusicpublishingthatoccurredat theendofthecenturycoincidedwiththeriseinpopularity ofthemadrigal,theluteayre,theconsortlesson,andthe lutelesson. Morley'sdeathin1603ledtoanotherperiodofunreg-ulatedmusicprintingduringwhichworkswereprintedby ThomasEast,PeterShort,andJohnWindet.East,whohad printedDowland'sTheSecondBookeofSongesorAyresin 1600,issuedThomasRobinson'sTheSchooleoflVlvsickein 1603.ShortprintedDOWland'sTheThirdandLastBookeof SongesorAyresin1603also.WindetprintedDowland's LachrimaeorSeavenTearesin1604.Barleywasgranted themusicpatentandwasadmittedtotheStationer'sCompany in1606.Hewassosuccessfulasapublisherofmusicthat heallowedhisassigneestoprintforhimfrom1609until hisdeathin1614.11 Duringthisperiod,severalworksby JohnandRobertDowlandwerepublishedbyThomasAdamsand otherassigneesofBarley.JohnDowland'stranslationof theMusiceactiveMicrologusofAndreasOrnithoparchus appearedin1609.BoththeVarietieofLute-Lessonsand A MvsicallBanquetappearedin1610,andDowland'sfinal llNewcomb,LuteMusicofShakespeare'sTime,p.xv. collectionoflutesongs,APilgrimesSolace,waspublished in1612(Seetable1). 19 Thetitle-pageborderoftheVarietieofLute-Lessons isbasedonadesignfirstusedinAntwerpin1566.12 This samedesignwasusedwithminormodificationsforthetitle-pagesofDowland'sTheSecondBookeofSongesorAyresand ThomasRobinson'sTheSchooleofrvrvsicke,bothofwhichwere printedbyThomasEast.Theborderwasalsousedforthe title-pageofA MvsicallBanquet,whichappearedduringthe sameyearastheVarietieofLute-Lessons.Neitherofthetwo last-namedworkscontainsanyacknowledgementoftheprinter thatproducedtheworksforthepublisher,ThomasAdams,but severalpiecesofevidencesuggestthattheVarietieofLute-Lessons,andprobablyA MvsicallBanquet,wereprintedby ThomasSnodham.SnodhamwasEast'sapprenticeandhetook overhismaster'sbusinesswhenEastdiedin1609.While theborderusedintheVarietieof hadbeenused byEastasearlyasthel570s,Eastgenerallylefttheoval atthetopoftheborderblankorfilleditwithsimple decorations,averse,oramusjcstave.Theovalinthe title-pageborderoftheVarietieofLute-Lessonsandb MvsicallBanquetcontainaviolanditsbowandalutein l2R.B.McKerrowandF.S.Ferguson,Title-pageBorders usedinEnglandandScotland1485-1640(London,1932),p.114, citedbyDianaPoultoninJohnDowland:HisLifeandWorks (UniversityofCaliforniaPress:BerkeleyandLosAngeles, 1972),p.247.(SeeFigure1). Table1 PrintingHistoryofSelectedEnglishMusicBooks,1596-1612 Composeror Compiler WilliamBarley JohnDowland ThomasMorley JohnDowland JohnDowland ThomasRobinson JohnDowland JohnDowland RobertDowland RobertDowland JohnDowland Publication ANewBookeofTabliture TheFirstBookeofSonges orAyres TheFirstBookeofConsort Lessons TheSecondBookeofSonges orAyres TheThirdandLastBooke ofSongesorAy'res TheSchooleof LachrimaeorSeavenTeares AndreasOrnithoparcusHis lVIicro1ogus VarietieofLute-Lessons AMusicalBanquet APilgrimesSolace Date 1596 1597 1599 1600 160) 160) 1604 1609 1610 1610 1612 Printer [JohnDanter] S[hort] WilliamBarley ThomasEast FteterJS[hort] Publisher WilliamBarley ThomasAdams ThomasMorley GeorgeEastland ThomasAdams ThomasEastSimonWaterson JohnWindetThomasAdams [ThomasThomasAdams [ThomasSnodhaniJThomasAdams [ThomasSnodham]ThomasAdams L[9wnes] JLohr!)BlJ:'owneJ Tl}lOma@S[podhamJ N o OF L COT E"feJJons:. Yi:.. F:ua6cs. P.Iuins, Ga1liarcls,Almaines,Corwaes, aad Vaks: ScIcctcd out of the bcftapproucd ,AVTHoas, aswell bcyolllhhcSeasas ofaJrowocCounay. "Vhereunto isannexeclcerrainc Ob .. fcnwiausbcIongingtoLVTE-playing: By 111m Bt!U" ofVifooti. AlW a Chort Tr=rife thereunto By111111 iNllWuJ Batchcler of c.MVSICK. Figure1.Title-pageoftheVarietieofLute-Lessons 21 22 frontofabookofmusic.Theovalissurroundedbythe inscriptionLaetificatQ!:.musica.Accordingtotiiargaret Dean-Smith,thisarrangementofthematerialintheovalis almostatrademarkofThomasSnodham'sprints.1J Furthermore, theactualelementsofprintingtypeusedintheVarietieof Lute-Lessonsforthetext,includingtheinitiallettersof severalsections,thelutetablature,andseveralpageborders matchtheelementsusedbyThomasEastforTheSchooleof Mvsicke.14 Dowland'stranslation,AndreasOrnithoparcvsHis Micrologvs,appearstohavebeenpressedfromthissametype also.ItispossiblethatThomasSnodhamprintedthelast-namedworkandA MvsicallBanquetaswellastheVarietieof Lute-Lessons.Thiscannotbeconfirmedhowever,becausethe pageborderthatappearsatthetopofsignaturesA2rand Brinthe~ a r i e t i eofLute-LessonsalsoappearsinLachrimae orSeavenTeares,whichwasprintedforDowland,' spublisher, ThomasAdams,byJohnWindet. lJMargaretDean-Smith,ReviewofRobertDowland,Varietie ofLute-Lessons,facsimileeditionbyEdgarHunt(London:Schott andCompany,1958)inTheLibrary,5thseries,14(1959):22J. TheinformationconcerningEast'searlyactivitiesderivesfrom thissourcealso. l4ThurstonDartstatesthat~ a s ttookoverthemusictype fontoftheFrenchHuguenotimigrant,Vautrollier,thatwas castfrompunchescutbyPetreiusofNuremberg,andsupplement-editwithnewfontsofDutchdesign."InadditionEastpro-videdhimselfwithup-to-datefountsofromananditalic lettersinvarioussizes,togetherwithsomefineinitial letters,borders,andblocks ... "ForewordtoA Plaineand EasieIntrodvctiontoPracticalllVlusickebyThomasIVlOrley, p.x. ReferencestoaPublicationContainingJohnDowland's LuteMusicand/orHisTreatiseonLute-Playing Onseveraloccasionspriqrtothepublicationofthe VarietieofLute-Lessonsin1610,JohnDowlandindicated thatheintendedtopublishacollectionofhislutemusic and/oratreatiseonfingeringlutemusic.Intheaddress liTothecourteousReader"ofTheFirstBookeofSongesor Ayres,heexpressesthisintention. TherehauebeendiuersLute-lessonsofminelately printedwithoutmyknowledge,falseandvnperfect, butIpruposeshortlymyselfetosetforththe choisestofallmyLessonsinprint,andalsoan introductionforfingering,withotherbookesof Songes,whereofthisisthefirst .. 15 23 ThisstatementprobablyreferstoseveralofDowland'spieces printedbyWilliamBarleyinANewBookeofTabliture.There isnoevidenceofDowland'shavingmadeanydefiniteplans foracollectionofhislutemusicorofhavingbegunwork ontheprojectatthattime. Dowlandexpressedasimilarconcernoverunauthorized publicationofhisworksintheaddressliTotheReader"of LachrimaeorSeavenTeares. HauinginforrenpartsmetdiuersLute-lessonsofmy composition,publishtbystrangerswithoutmynameor approbation;Ithoughtitmuchmoreconuenient,that mylaboursshouldpasseforthvndermineowneallow-ance,receiuingfrommetheirlastfoileandpolish-l5JohnDowland,liTothecourteousReader,"inTheFirst BookeofSongesorAyres(London,1597),moderneditionbased onthereprintof161),ed.byEdmundH.Fellowes,rev.by ThurstonDart(London:StainerandBell,1965),p.1. ment;forwhichconsiderationIhauevndergonethis longandtroublesomeworke . 16 However,theselectionsinLachrimaeorSeavenTearsare arrangedforaconsortoffiveviolsorviolinsandlute ratherthanforsololute.Dowlandseemstohavemadeno otherreferencestothepublicationofhisluteworksin aprintedcollection.ThelutepiecesbyDowlandinthe VarietieofLute-Lessonsandinthesongbooksthatheand hisson,Robert,producedaretheonlypiecesthatJohn Dowlandpublished. 24 Dowlanddidmakeanotherreferencetoatreatiseabout luteplayingintheaddressliTotheReader"ofAndreas OrnithoparcusHisMicrologus. Myindustryandon-sethereinifYOU_friendlyaccept (beingnowreturnedhometoremaine)shallencourage meshortlytodiuulgeamorepeculiarworkeofmine owne:namely,MyObseruationsandDirectionsconcern-ingtheArtofLute-playing:whichInstrumentasof allthatareportable,is,andeuerhathbeenmost inrequest,soisitthehardesttomannagewith cunningandorder,withthetruenatureoffingering; whichskillhathasyetbynoWriterbeenrightly expressed:whatbymyendeuoursmaythereinbeattain-ed,IleauetoyourfutureIudgement,whentimeshall producethatwhichisalreadyalmostreadyforthe Haruest.17 16JohnDowland,liTotheReader,"inLachrimaeorSeaven Teares(London,1601t),facsimileedition,"EarlyMusicRe-printed,"no.1,RichardRastall,generaleditor,commentaryby WarwickEdwards(Leeds,England:BoethiusPress,1974),sig.A2v. 17JohnDowland,"TotheReader,"inAndreasOrnithopar-cusHislVlicrologus(London,1609), 'dIeeditioninP; CompendiumofMusicalPractice:Musice micrologusby AndreasOrnithoparchusandAndreasOrni thoparcusHisNiicrol-ogus,orIntroduction:ContainingtheArtofSingingbyJohn Dowland,ed.byGustaveReeseandStevenLedbetter(NewYork: DoverPublications,1973),p.116. 25 If,asthisstatementimplies,Dowlandhadalmostfinished anextendedtreatiseonthefingeringoflutemusicin1609, itwouldhavemadelittlesensetosubstitutethetreatise onfingeringbyJean-BaptisteBesardfor- Dowland'streatise intheVarietieofLute-Lessonsayearlater.A statement byRobertDowlandintheaddressliTotheReaderswhosoeuer" ofthelattervolumeconfirmsthatJohnDowland'streatise onluteplayingwasnotcompletewhentheVarietieofLute-Lessonswaspublished. ButwhatsoeuerIhaueheredone(vntillmyFatherhath finishedhisgreaterWorke,touchingtheArtofLute- 18 playing,)Ireferreittoyouriudiciouscensures .... The"OtherNecessaryObseruationsbelongingtotheLVTE,II whichJohnDowlandcontributedtotheVarietieofLute-Lessons,mayhavebeenextractedfromalargerworkin progressatthetime,butthereferenceof1609statesthat Dowland'streatiseconcernedthefingeringoflutemusicand thisispreciselythesubjectcoveredinBesard'streatise. Dowland'scontributiondealswithperipheralsubjects,such asstringing,fretting,andtuningalute,thatarenotcov-eredinBesardastreatise,anditgivestheappearanceofan addendumtoBesard'scontribution.Themannerinwhich Dowland'streatisecomplementsBesard'streatisesuggests thatDowlandaddedhistreatisetotheVarietieofLute-Lessons 18""-RobertDowland,TotheReaderswhosoeuer,lnVarietie ofLute-Lessons(London,1610),facsimileeditioned.byEdgar Hunt(London:SchottandCo.,1958),p.4. tolendtheweightofhisreputationtoaworkthatwas ostensiblyhisson'sproduct. SeveralreasonsmayaccountforJohnDowland'sfailure topublishtheextendedworkonlute-playingtowhichhe madereference.Thefirstandleastlikelyisthathemay havebeentoooldtocompletesuchawork.Intheaddress liTotheReaderswhosoeuer"oftheVarietieofLute-Lessons, RobertDowlandreferstohisfatheras" beingnow 26 gray,andliketheSwan,butsingingtowardshisend . ,,19 SinceJohnDowlandwouldhavebeenonlyforty-eightyearsold in1610,thereferencemayhavebeenusedfigurativelyto suggestadeclineintheelderDowland'screativepowers. Yettwolater,JohnDowlandpublishedA Pilgrimes Solace,hisfinalcollectionoflutesongs,whichcontains someofhisfinestworks.ThestatementmayrefertoJohn Dowland'sabilitiesasaperformerifitistobeaccepted asanythingmorethanarhetoricaldevice,However.twoyears laterJohnDowlandreceivedhislong-sought-afterappointment totheKing'sMusickandheheldthatpostuntilhisdeath in1626. A moreplausibleexplanationofDowland'sfailureto publishhisextendedtreatiseonlute-playingcanbefound inthe publictasteinmusicalfashionsduringthe earlyyearsoftheseventeenthcentury.JohnDowland's 19Ibid 27 address"TotheReader"inAPilgrimesSolacecontainsa lengthydiatribeinwhichDowlandcomplainsaboutthepoor reception.givenhimbyhiscountrymenwhenhereturnedfrom Denmark. SohaueIagainefoundstrangeentertainement sincemyreturne:especiallybytheoppositionoftwo sortsofpeoplethatshroudetheseluesvnderthetitle ofMusitians.ThefirstaresomesimpleCantors,or vocallsingers,whothoughtheyseemeexcellentin theirblindeDiuision-making,aremeerelyignorant, eueninthefirstelementsofMusicke, ... yetdoe thesefellowesgiuetheirverdictofmebehindemy backe,andsay,whatIdoeisaftertheoldmanner: butIwillspeakeopenlytothem,andwouldhauethem knowthattheproudestCantorofthem,daresnotoppose himselfefacetofaceagainstme.Thesecondareyoung-men,professersoftheLute,whovauntthemselues,to thedisparagementofsuchashauebeenebeforetheir time(whereinImyselfeamaparty)thatthereneuer wasthelikeofthem Moreouerthathereareand dailydothcomeintoourmostfamouskingdome.,diuers strangersfrombeyondthe~ e a s ,whichauerrebefore ourownefaces,thatwehauenotruemethodeofappli-cationorfingeringoftheLute.20 Dowland'sresentmentofyoungerlutenistsmusthavebeen acuteforhimtohaveincludedthesecommentsinapublica-tiondevotedtohislutesongs.Whiletheselutenists createdcompetitionforDowland,theforeignerstowhichhe referswerepopularizingastyleofluteplayingthatposed agreaterthreattoDowland'slivelihood.Thestylebrise: whichdevelopedinFranceduringtheearlyyearsofthe seventeenthcentury,departedradicallyfromthestyleof 20JohnDowland,"TotheReader,"inAPilgrimesSolace (London,1612),moderneditioned.byEdmundH.Fellowes, rev.byThurstonDart(London:StainerandBell,1969),p.1. 28 luteplayingthathadbeeninusesincethebeginningofthe sixteenthcenturythroughoutEurope.Compositionsinthenew styleutilizednewtuningsforthelutethattookadvantage oftheever-increasingnumberofbasscoursesontheinstru-menteFurthermore,intheseworks,ornamentationisan essentialpartofthemelodicandtexturaldesignrather thanadecorativeoptionavailabletotheperformer.The growingpopularityoftheFrenchstyleofplayingthelute andcomposingforitcouldonlyhinqerDowland'scareersince hewasanadmittedchampionoftheoldstyleofplaying. CompetitionfromtheFrenchschooloflutenistswas onlypartofDowland'sproblem.Thevioladagambaandthe brokenconsortwerebecomingincreasinglypopularduring thefirstyearsoftheseventeenthcenturyandchallenged thepre-eminentpositionoftheluteinthemusicalworld ofDowland'sday.In1605,TobiasHumepublishedacollec-tionofmusicforthelyraviolcalledTheFirstPartof Ayres,French,Pollishandothersthatcontainedthe followingstatement. Fromhenceforth,thestatefullInstrumentGamboVioll, shallwitheaseyeeldfullvarious,anddeuicefull astheLute:forhereIprotesttheTrinitie ofMusicke,Parts,Passion,andDeuision,tobegrace-fullyunitedintheviol,asinthemostreceiued Instrumentthatis&c.2l 2lTobiasHume,"TothevnderstandingReader,"inThe FirstPartofAyers,French,Pollish,andothers(London, 1605)quotedbyJohnDowlandin"TotheReader,"inP; PilgrimesSolace.SeeDianaPoulton,JohnDowland,p.75, forafurtherdiscussionofthelyraviolinEngland. 29 Dowlandrespondedtothisstatement,whichhequotedinthe address"TotheReader"inA PilgrimesSolace,asfollows, "WhichImputation,methinkes,thelearnedersortofMusitians ,,22 oughtnottoletpassevnanswered.Hethencallsupon theyoungerlutenistsofhisday,whodisdainedDOWland's conservativeoutlook,tocometo vndertakethedefenceoftheirLuteprofession, seeingthatsomeofthemaboueother,hauemostlarge meanes,conuenienttime,andsuchencouragementasI neuerknewanyhaue . Perhapsyouwillaskeme, whyIthathauetrauailedinmanycountries,andought tohauesomeexperience,dothnotvndergoethis busines'myselfe?IanswerethatIwantabilitie, beingIamnowenteredintothefiftiethyeareofmine age:secondlybecauseIwantbothmeanes,leasure,and encouragement. 23 ThesecommentsinvitespeculationthatDowlandmayhave lackedthetimetofinishhistreatiseonlute-playing duetofinancialhardships,butthispremisecannotbe conf.irmed.Giventherhetoricaltoneoftheaddress,these commentsareprobablyjustanotherexpressionofhisdis-c o n t e n t ~dueinparttohisfailuretoobtainapostasa lutenistintheroyalmusicalestablishment.TheJ'acobean courtfavoredelaborate,stagedentertainmentsinvolving dancingandsingingina'Superficialdramaticcontextrather thantheseriousworksthatdominate,dDowland'soutputduring thisperiodofhislife.WhenDowlanddidfinallyobtaina 22JohnDowland,"TotheReader,"inA PilgrimesSolace, p.1. 30 postatCourtlaterinthesameyear,hispositionwasnot thatofChiefLuter,butratheroneoflesserimportancethat entitledhimtoasmallersalary.Furthermore,thesalaries ofalltheEnglishlutenistsintheKing'sIViusickweresub-stantiallysmallerthanthesalarypaidJohnrlJariaLugario, aforeignerwhoheldthepostofQueen'sMusicianatthat t.24 l.me. Thecompetitionofyoungerlutenistsandcomposers, therisingpopularityofthelyraviolandthebrokencon-sort,andthemusicaltasteoftheJacobeanCourtmayhave convincedDowlandthattherewasnopointincompletingand/ orattemptingtopublishhistreatiseonlute-playingafter 1610.However,thepopularityofDowland'spiecesinthe manuscriptcollectionscompiledduringthefirstquarterof theseventeenthcenturysuggeststhatsuchaworkwouldstill havebeenwellreceived.Althoughthereasonsarenotclear, the "OtherNObtb1.ttheLVTE".ecessaryserualonse_onglng0 constituteDowland'sonlypublishedwritingsonthesubject. Whileafewchartsandmusicalexamplesinmanuscriptsources oflutemusichavebeenattributedtoDowland,nowritten discussionoflute-playingappearsinanyofthesesources. Similarly,therearenoreferencesbycontemporarywriters toanyotherworkonlute-playingbyJohnDowland. 24DianaPoulton,JohnDowland,p.74.Seealso,John Ward,"ADowlandMiscellany, "AppendixK.TheKing'sLuters, 1593-1612,JournaloftheLuteSocietyofAmerica10(1977); 107-109;concerningDowland'ssalary,andpp.20-3concerning thenatureofhispost. RobertDowland'sRoleintheProduction oftheVarietieofL u t e - L e s s ~ VerylittleisknownaboutRobertDowland'slifethat wouldestablishhisqualificationsasalutenist,composer, oreditoroflutemusic.TheVarietieofLute-Lessonsis 31 dedicatedtoSirThomasMonson,inwhosehouseholdRobert livedforseveralyears(SeeFigure2).Robertwasprobably indenturedtoSirThomasMonsonduringhisyouthwhile JohnDowlandservedattheCourtofChristianIVofDenmark. RobertmayhavereceivedmusicalinstructionfromSimon Merson,alutenistwhoservedinMonson'smusicalestablish-mentbeforebecomingoneoftheKing'sLuterstOoJames1.25 DianaPoultonreferstoSirThomasMonsonas"aprominent courtierandagreatamateurofmusic[who]pridedhimself onhismusicalestablishment,especiallyonthequalityof h"",,26 1Sslngers...Robert ISassociationwiththeiVlonson householdistheonlyinformationthathascometolight abouthisactivitiesduringhisearlyyears. Accordingtoastatementonhismarriageallegation, executedin1626,Robertwasthen"aboutXXXVyeares"of age.Thiswouldmeanthathewasbornaround1591andwould havebeenapproximatelynineteenyearsoldwhentheVarietie ofLute-Lessonswaspublished.Robertmusthaveachieved 25JohnWard,"ADowlandMiscellany,"p.7. 26DianaPoulton,JohnDowland,p.64. TO THE RIGHT WORSHIP-FVLL, \lVORANDVERTVOVS Knighr, Sir 'Tbomssounlol:. Y R, the gratefull remembrance of yom bountie tome,in part of myEducation,whilfi: my Father was abfent &omEngland, hath embouldned me to prefentthele myfirLl: Labourstoyourworthi.. ncs,affuring my thatthey Muftcall willbe acceptableto thePatron of ;;;W Il!ttlt!, and being onely out of duety Ded'Clted, you will dame to receiue them as a poore Teftimonieofhis gratitude, who acknowledgetb. bimfelfe for eller wabJeby his vttermoftfcruicetomerityour Fauours.All that I can istopray to Almighty God for the health and profperitieof You andYwhich 1willneuer cealetodoe& Figure2.DedicationoftheVarietieofLute-Lessons 32 33 someproficiencyasaperformerontheluteduringthelatter partofhislifebecausehevisitedthecourtoftheDukeof WolgastinPomeraniaaslutenistforatroupeofEnglish actorsin1623.WhenJohnDowlanddiedin1626,Roberttook overhispostattheCourtofCharlesI.Robertheldthat positionuntilhisdeathin1641.27 ItisuncleartowhatextentJohnDowlandassistedhis sonintheproductionoftheVarietieofLute-Lessons.'I'he titlepageoftheprintindicatesthatthelutepiecesin thecollectionwereselectedbyRobertDowland,andthat the"OtherNecessaryObseruationsbelongingtotheLVTE" werewrittenbyhisfather.RobertDowland'saddress"To theReaderswhosoeuer"intheVarietieofLute-Lessons containsadditionalinformationaboutRobert'sroleinthe productionoftheprint(SeeFigure3). Gentlemen:Iamboldtopresentyouwiththefirst fruitsofmySkill,whichalbeititmayseemehereditarie vntomee,myFatherbeingaLutenist,andwellknowne amongstyouhereinEngland,asinmostpartsofChristen-domebeside.Iamsureyouarenotignorantofthatold saying,LaboreDeumomniavendere:Andhowperfectionin anyskillcannotbeattainedvntowithoutthewasteof manyyeeres,muchcost,andexcessiuelabourandindus-trie,whichthoughIcannotattributetomyselfe,being butyounginueeres,Ihaueaduenturedlikeadesperate SouldiertothrustmyselfeintotheVant-gard,andto passethePikesofthesharpestCensures,butItrust withoutdaunger,becausewefindeittrueinNaturethat thosewhohauelouedtheFather,willseldomehatethe Sonne.AndnotvnlikeinreasonthatIshoulddistast all,sincemymeanesandhelpesofattainingwhatIhaue, 27 Ibid.,pp.28,86-92. To the 7, _"- h""=>""=>.."'t). A .....C'I .'-"l. '\" l!'\".C'I'\"

... ...1I 14444113141411 G3lliard.:23:3:23 :2 rFFrrrFFr

l J? I]'? '271 { 52-'. 9I'.\1. '\" t2 '!t3!! 3?!.. 3 1 Q 31;'3 1 :2 flF 4!I:23! 3 Figure15,AGal1iardbyThomasRobinson fromTheSchooleofNiusicke,sig,D2v .L 171 172 duplegroupingimpliedbythesuccessionofstrongandweak articulationsproducedbythethumbandthefingers. Thefingeringofdoublestops,triplestops,andchords offourormorevoicesisunaffectedbytripledivision.of thebeatbecausethethumbplaysthebassnotesofallthese configurations.Hence,incontinuouspassagesofmultiple stops,therearenostrong/weakarticulationsindupleor triplemeter.Similarly,passagesofsinglestopsconsisting entirelyofsemibrevesandminimsareunaffectedbytheuse oftriplemeterbecausethethumbplaysallsingle-stopsin thesenotevalues.therebyeffectivelydisposingofaccentual differencesbetweensuccessivenotesinthesevalues.Since themetricalprincipleoforganizationoffingeringpatterns isonlyconcernedwithnotesshGrterthanaminim,thestrong/ weakarticulationsproducedbythesepatternshavenosignif-icanceonthelevelofthetablaturemeasuresandthebarlines innowaydenotestressedinitialbeatsthatdifferfromthe stressedbeatsofminimsubdivisionsofthemeasure. Inpassagesofsinglestopsconsistingofvaluesshorter thanaminim,thenormalrulesoffingeringcanbeapplied toanygroupoftwoorfournoteswithintheframeworkof apieceinatriplemeter.Theonlyinstancesinwhich problemsarisefromtheapplicationofrulesbasedimplicitly onthealternationofstrongandweakaccentsareasfollows: (1)simpletriplemeterinvaluesshorterthanaminim,(2) compoundtriplemeter,and(3)triplets.Ineffect,allthree 173 ofthesecasesareidentical(forpurposesoffingering) becausetheyeachcontainthreenoteswithintheprevailing subdivisionofthebeat. Whiletherearemanyselectionsintriplemeterinthe lutetutors,veryfewofthemcontainfingeringmarks.The fingeredselectionsconsistofgalliardshavingthreeminims toabarandseveralindividualselectionswiththreecrotchets toabar.Thefingeringsinthegalliardsconformtothe patternsestablishedintherulesforduplemeter.Theonly fingeredexamplesoffasttripletimewiththreecrotchetsto ameasureare"BockingtonsPound"and"rilistrisWintersJumpe tII bothofwhichappearinBarley' sA Q!-1'.abli ture. 99 Barleyutilizesthethumbonthefirstandthirdcrotchets andtheindexfingeronthemiddlenoteofonemeasureinthe latterpiece. atasimilarpointinthesamepiece, heindicatestheuseofthethumbonallthreecrotchets. Itispossibletoplaysinglestopsinvolvingtriple subdivisionoftherhythmicpulseusingthethumbonthefirst subdivisionandtheindexfingerandmiddlefingeronthe successivesubdivisionsineitherorder.Whilethereare nodocumentedinstancesofthispracticeinthelutetutors, Robinson'suseofthemiddlefingerandtheringfingersug-geststhathemayhavesanctionedtheiruseinthisfashion, butthisisonlyconjecture.Ontheotherhand,Besard's 99BarleYtII AXlInstrvctiontotheOrpharion, IIinA New of sigs.C4v-Dr(SeeFigure16). --- . -.-- - .. _... -r-- -.-r - .. ,.E_. .- .C.t_0.0'".==::400_ ... __ I.: N.a. NSTB.V,C:T,I 0N\T;O"T H,.1l,"H;.R1.0."- -A- ,t43 '"Fs: "'-' -, "- ,-,,4:'"fJ __1I if t , r : f'rr" t ';:r' Ii, 4.,.,,- J,""41- C/:f..e....fCJtIGe_.F. " ......_.. 2i'Ii .... II...... 'r " '1 . i ' . .-!" ... - ._- --" ace::w= .. . D Figure16.MistrisWintersJumpebyJohnDowland,:from"AnIn-strvctiontotheOrpharion."inANewBookeo:fTab1iture,sig.DrI ..... --.J +=-175 limiteduseofthemiddlefingerandtheringfingermake itdoubtfulthathewouldhaveutilizedtheminthisfashion. TextualVariationsinDifferentEditionsofBesard'sTreatise Asnotecpreviously,Besardostreatiseonfingering appearedinfourdifferentpublications,includingtwoLatin versionsbyBesard,theEnglishtranslationbyGowland,and aGermantranslationofthesecondLatinversion.Italso appearedinanumberofcontemporarymanuscripts inoneformoranother. 100Theoriginalversionofthetrea-tiseappearedintheHarmonic us ,publishedseven yearsbeforetheof..1ute-Lessons,andtherevised Latinversionappearedinthe publishedseven yearsafterDowland'sprint.TheGermantrans1atfonappeared underthetitleIs:goge .inthesame yearandplaceastheNovusWhiletherevisions introducedbyBesardintothesecondLatinversionofthe treatisewereintendedtoupdatethework,thetextualvari-antsintheEnglishandGermaneditionsmaybeerrorsor intentionalmodificationsintroducedbythetranslators withoutBesard'sknowledge.Inanyevent,thefourversions ofBesard'streatisedocumentanumberofdevelopmentsin lutetechniquethatoccurredduringthefirstpartofthe seventeenthcentury. 100JuliaSutton,"TheLuteInstructionsofJean-Baptiste," MusicalQuarterly51(1965):345.Thebulkoftheinformation concerningtheeditionsof1617isfromresearchbySutton appearingintheworkscitedinthissectionofthethesis. 176 Thediscrepanciesbetweentheoriginalversionofthe treatiseandtheEnglishtranslationofitareminor.In the 5ide-headingshavebeenintro-ducedthroughoutthetext.Inaddition,barlineshavebeen addedtotheexamplesillustratingtherulesforthefinger-ingofsinglestops.Inthefirstofthese,thefourthstop ofBesard'sversionhasbeenomitted.Intheexamplesof fingeringpracticeinmultiplestops,sevenchordshavebeen omitted,fourchordshavebeenaltered,andfivechordshave beenrefingered.Someofthesefingeringchangesmakethe chordseasiertoexecutewhereasothershavelittleeffect. Theexamplesofright-handfingeringpracticecontainasingle alteredchord,butasnoted,thedesignationsofright-hand fingeringsthatappearinBesard'soriginalversionhave beenreplacedbytheappropriateleft-handfingeringsinmost ofthemultiplestops,withtheexceptionoftheexamplefor thefourthrule(SeeFigure17). Besard'sownrevisionsinthesecondLatinversionof thetreatisearemoresignificantthanDowland'schanges. -IntheBesardaddedhisownsubheadingsafter themannerofthosefoundintheVarietiLofInadditiontoextendingtheintroductoryandconcluding remarks,headdedanumberofsentencestoclarifyoralter hisearliertext.Thesectiondealingwiththechoiceofa luteforabeginnercontainsthefollowingaddition. Takealutewithatleasttenstrings,orcourses,unless youpreferalargerone(asisthepracticeinItalyand DEMODOINTESTVD1NE.STVDENDJtJB!tLVS.177 g -'11914.*9.,_ --------_______---......---_____________'Ill-lsIICl--II----------------&-*,e.,---------------------------------------------"'in hocaltcro - . \'... --. ... -,'._.,'. -. &cmplum ill quo rabm l'rimis choris.duIDawluDt -------------------------------------------------------- -_.. _, '..:,,---'-------:...-

_____... _. _____ -..:.:.......:.;..:. ....:.,,,;,.:. !:-....:...:...__ ex>t'-r-I "HIII"' "nn . ,. j III J t: 'I H I tqt .. T! iflt tf.t 1Jttt 1_"f !!tlcTs I 1_- _ 'I'nUllI;" . It111 .. 4II I LI; 1 1I "*-_ ...... flH!.j;1"w 1111 hi... r ,tlffi11 LtlIl. j1. ,Allllhli. flVoll 11if! .l i'I !j 1Tt11 .11. 'Il.l-:I !1t caT 'i> X- J11:,frl!! *' .'I'tttt .....J ttl .rr11 ;t -tTt. ltfl IL1itt, * iT ..'Trl!1 ... Jft11111 t'I2I.11'I r ...Tt ..."r11111\1.1 . :.r"1t .ltii- I.; ... ; x 179 .