New Taylor, Ryan Campbell (2019) metaphors of vision.theses.gla.ac.uk/74293/1/2019TaylorPhD.pdf ·...

Transcript of New Taylor, Ryan Campbell (2019) metaphors of vision.theses.gla.ac.uk/74293/1/2019TaylorPhD.pdf ·...

-

Taylor, Ryan Campbell (2019) Accounting conceptual frameworks and

metaphors of vision. PhD thesis.

https://theses.gla.ac.uk/74293/

Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author

A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study,

without prior permission or charge

This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first

obtaining permission in writing from the author

The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any

format or medium without the formal permission of the author

When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author,

title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given

Enlighten: Theses

https://theses.gla.ac.uk/

https://theses.gla.ac.uk/74293/https://theses.gla.ac.uk/mailto:[email protected]

-

i

Accounting Conceptual Frameworks and Metaphors of Vision

RYAN CAMPBELL TAYLOR

A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Glasgow

for the degree of doctor of Philosophy

Adam Smith Business School

Department of Accounting and Finance

Research Undertaken at the University of Glasgow

-

ii

ABSTRACT

The aim of the research was to analyze the evolving particularly subconscious conceptual

metaphor in Western society: Vision as Knowledge amidst the post-modern turn. This is done

in a selection of accounting conceptual frameworks from 1978 to 2015. The motivation for

analysis was first to discover what visual knowledge was like in accounting conceptual

frameworks. Vision is a metaphor that functions largely unrecognizably in accounting, as

well as other, discourse (Lakoff and Johnson, 1980, 1999, Sweetser, 1990, Gibbs, 2017). By

isolating these sunk vision metaphors, the thesis attempted to see if the metaphor, vision as

objective knowledge, had altered amidst the postmodern turn. Since the research approach

here is a corpus analysis of submerged vision metaphors in conceptual frameworks, the

methodology employed sought to isolate, select, and categorize vision metaphors in a

longitudinal study of conceptual frameworks over the periods of 1978 to 2015.

The thesis’s contribution concerns the submerged character of vision metaphor that pervades

everyday language. Vision is largely unrecognizable as a metaphor for conceptualizing

objective knowledge in Western society. And so, in order to understand vision metaphor’s

transition from modernity to postmodernity and what this may mean in relation to accounting

knowledge, a method is used to extract vision metaphors. A method is developed to study

vision periodically in order to study how accounting regulation has evolved metaphorically

over the last few decades. The results from the thesis demonstrates that vision as knowledge

is conceptualized differently over time in accounting conceptual frameworks. From an

absolute viewing perspective concerning the mind (Vision as Mind) where primacy is

attributed to the intellect, to a much more embodied, human, situated perspective, the thesis

informs the construction of vision as knowledge in terms of the body (Vision as Body). What

the implications of this shift may mean for accounting is discussed later in the thesis.

The thesis follows a conventional structure. It begins with a review of the accounting

literature, followed by a theoretical overview, and an exploration of the empirical site that is

chosen for such an analysis. A methodology and methods chapter follows, and then finally

a key findings and related discussion chapter is provided. To recapitulate, the main aim of

the thesis is to understand the transformation of the Vision as Knowledge metaphor over the

period of conceptual frameworks chosen in this study. The main findings from the thesis is

that the Vision as Knowledge metaphor has typological frames in accounting conceptual

frameworks, which shows the gradual deconstruction of a strong representational mode of

thinking in accounting regulation overall.

-

iii

-

iv

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... ii

Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................... ix

Declaration ................................................................................................................................. x

Chapter 1 – Introduction, Research Questions and Method ...................................................... 1

1.0 Introduction: Accounting and Vision metaphor ................................................................... 1

1.1 Thesis’ Focus: Vision Metaphor .......................................................................................... 3

1.2 Vision: Explaining The Metaphor’s Evolving Character ..................................................... 4

1.3 Hypothesis: Vision as a Submerged Metaphor for Objective Knowledge .......................... 6

1.4 Conceptual Frameworks as the Empirical Site .................................................................... 7

1.4.1 Types of Frameworks ........................................................................................................ 8

1.5 Research Questions and Aims .............................................................................................. 9

1.6 Research Questions’ Importance for Critical Accounting ................................................. 10

1.7 Method: A Corpus Based Content Analysis ...................................................................... 11

1.8 Step 1 - Identifying Vision Metaphors ............................................................................... 12

1.8.1 Step 2 - Categorizing Vision metaphors ......................................................................... 13

1.8.1.2 Deliberate Vision Metaphors ....................................................................................... 13

1.8.1.3 Submerged (Non-Deliberate) Vision Metaphors ......................................................... 14

1.8.2 Step 3 - Basic Trends and Patterns: Concordance Analysis and Close Reading ............ 15

1.9 Thesis Layout ..................................................................................................................... 16

1.9.1 Chapter 2 - Literature Review ......................................................................................... 16

1.9.3 Chapter 3 – Theoretical Discussion ................................................................................ 17

1.9.4 Chapter 4 - Conceptual Framework Overview ............................................................... 17

1.9.5 Chapter 5 - Methodology and Method ............................................................................ 18

1.9.5.1 Methodology ................................................................................................................ 18

1.9.5.2 - Method ....................................................................................................................... 19

1.9.6 Chapter 6 - Results .......................................................................................................... 20

1.9.7 Chapter 7 - Thesis Conclusion ........................................................................................ 20

Chapter 2 - Literature Review .................................................................................................. 22

-

v

2.0 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 22

2.1 Accounting and metaphor .................................................................................................. 23

2.1.1 The Literal: Visual accuracy of the Outside World ........................................................ 24

2.1.2 Metaphorical Overtness .................................................................................................. 24

2.1.3 How is Metaphor Understood in the Accounting Literature ........................................... 25

2.1.4 A Different View on Metaphor: Submerged Metaphor .................................................. 27

2.1.5 Structure of the Chapter .................................................................................................. 31

2.2 Vision, Literal and Scientific Accounting Knowledge ...................................................... 31

2.2.1 Literal Financial Accounting: Solomons and Visual Representation ............................. 33

2.3 Accounting as Metaphor .................................................................................................... 34

2.3.1 Accounting as a System of Signs .................................................................................... 34

2.3.2 Accounting as Maker of Social Reality .......................................................................... 38

2.3.3 Accounting Sustains Social Reality ................................................................................ 40

2.4 Metaphors in Accounting: Gaining Access to Social Constructions ................................. 42

2.4.1 Accounting as a Humanist Pragmatic Will ..................................................................... 46

2.4.2 Losing Access to Social Reality ...................................................................................... 49

2.5 The Financialization of the Economy and Financial Accounting ...................................... 52

2.5.1 Hyper-reality as a Complex Social Reality ..................................................................... 53

2.6 The Difficulty of Access: The Prison House of Metaphor ................................................ 58

2.7 Overview: Accounting as Overt Metaphorical Language .................................................. 66

2.8 Going Beyond: Between the Literal and Metaphorical ...................................................... 71

2.8.1 A Turn to Objects – Submerged Metaphors ................................................................... 72

2.8.2 Actor Network Theory, Ontological Politics and Metaphor ........................................... 73

2.9 Chapter Summary ............................................................................................................... 75

Chapter 3 - Vision, Objectivity, and Knowledge ..................................................................... 77

3.0 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 77

3.1 Megill: Four Senses of Objectivity .................................................................................... 82

3.1.1 Absolute Objectivity ....................................................................................................... 83

3.1.2 Disciplinary Objectivity .................................................................................................. 84

3.1.3 Dialectical Objectivity .................................................................................................... 85

-

vi

3.1.4 Procedural Objectivity .................................................................................................... 86

3.2 Deconstructing Objective Knowledge: Things Ordered by and Through Accounting ...... 88

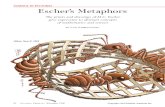

3.2.1 The Renaissance Eye: Constructing the Objective Viewer ............................................. 90

3.2.2 Northern Art – The Landscape ........................................................................................ 96

3.2.3 From Modernity to Postmodernity .................................................................................. 99

3.3 Conclusion – Things Ordered by and Through Accounting ............................................ 104

3.4 Conceptual Frameworks: Submerged metaphorical language ......................................... 105

Chapter 4 - Accounting Regulation: Conceptual Frameworks .............................................. 107

4.0 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 107

4.1 The AICPA 1971- 1973 ................................................................................................... 109

4.2 The FASB Conceptual Framework (1978 – 1985) .......................................................... 110

4.3 The International Accounting Standard Board (1989) ..................................................... 114

4.4 The UK Accounting Standards Board (1999) .................................................................. 117

4.5 The International Accounting Standards Board (2010) ................................................... 118

4.6 International Accounting Standard Board’s Exposure Draft (2015) ................................ 121

4.7 Chapter Summary ............................................................................................................. 124

Chapter 5 - Methodological Approach: Vision and Embodied Cognition ............................. 128

5.0 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 128

5.1 Side Stepping the Metaphorical/Literal Binary ................................................................ 130

5.1.1 Chapter Structure .......................................................................................................... 132

5.1.2 Purpose and Underlying Logic of the Chapter .............................................................. 133

5.1.3 Importance of Methodology: Answering the Research Questions ............................... 134

5.2 Primacy of the Body ......................................................................................................... 137

5.3 Conceptual Metaphor: Vision is Knowledge ................................................................... 141

5.3.1 Vision as Passive Knowing ........................................................................................... 145

5.3.2 The Sedentary Body and Vision ................................................................................... 148

5.4 Two Types of Vision Metaphor: Deliberate and Submerged Metaphor .......................... 152

5.4.1 Deliberate Vision Metaphors ........................................................................................ 154

5.4.2 Non-Deliberate/Submerged Vision Metaphors ............................................................. 157

5.4.3 The Importance of Metaphors Submerged in Thought ................................................. 159

-

vii

5.5 How Does the Methodology Link with Method? ............................................................ 162

5.5.1 The Indo-European Root ............................................................................................... 164

5.6 How the Method is Deployed .......................................................................................... 166

5.6.1 Step 1- Beginning the Process of Identification ............................................................ 170

5.6.2 Step 2 - Identifying Submerged Vision Metaphors Using Etymology ......................... 171

5.6.3 Step 3 – Deliberate Metaphors Discovered ................................................................... 173

5.6.4 Step 4 –Categorize Submerged Metaphors Using Proto Language .............................. 173

5.6.5 Step 5 – Three Submerged Vision Metaphors: Active and Inactive ............................. 177

5.6.5.1 Inactive Indo-European Roots .................................................................................... 177

5.6.5.2 Active Roots ............................................................................................................... 179

5.6.6 Step 7 - Concordance Analysis ..................................................................................... 180

5.6.7 Step 8 - A Closer Reading of Submerged Active and Inactive Roots .......................... 180

5.7 Chapter Summary ............................................................................................................. 181

5.8 Limitations and Reflection on Embodied Cognition Methodology ................................. 183

Chapter 6 – Results ................................................................................................................ 188

6.0 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 188

6.1 Deliberate and Submerged Vision Metaphors ................................................................. 191

6.2 Deliberate Metaphors ....................................................................................................... 192

6.3 Submerged Vision Metaphors: Active and Inactive Types .............................................. 197

6.4 Submerged Inactive Vision Metaphors ............................................................................ 198

6.4.1 Indo European Root = Observation/Observing ............................................................. 198

6.4.2 Indo European Root: Recognition = Knowledge (Epistemology) ................................ 200

6.4.3 Indo European Root: Representation = Existence (Object-ivity) ................................. 201

6.5 Submerged Active Vision Metaphors .............................................................................. 201

6.6 Active and Inactive Submerged Vision Metaphors ......................................................... 204

6.6.1 Active and Inactive Indo-European Roots .................................................................... 205

6.6.2 Overall: The Transition in Submerged Active Metaphors ............................................ 206

6.6.3 Active Vision Categories .............................................................................................. 207

6.7 FASB 78-85 - IASB 1989: Moving Away From Vision ................................................. 208

6.7.1 From FASB 78-85 - IASB 1989 ................................................................................... 208

-

viii

6.7.2 Movement from IASB 1989 – ASB 1999 ..................................................................... 210

6.7.4 Movement from ASB 1999 – IASB 2010 ..................................................................... 212

6.7.4 Movement from IASB 2010 – IASB 2015 ................................................................... 214

6.8 Inactive Categories ........................................................................................................... 216

6.8.1 FASB - IASB 1989: Knowing as Recognizing ............................................................. 217

6.8.2 IASB 1989 – ASB 1999: Inactive Vision Metaphors - Observing ............................... 219

6.8.2.1 ASB 1999 - Evidence Gathering ................................................................................ 219

6.8.2.2 ASB 1999 - Guise and Envisage ................................................................................ 220

6.8.2.3 IASB 2010 and 2015 Exposure Draft - Vision and Outlook ..................................... 221

6.8.3 IASB 2010 and IASB 2015: Inactive Vision Metaphor – Existing .............................. 222

6.9 Discussion and Summary of Results ................................................................................ 223

Chapter 7 - Conclusion to Thesis ........................................................................................... 226

7.0 Answering the Research Questions .................................................................................. 226

7.1 Accounting Conceptual Frameworks and Political Ontology .......................................... 228

References .............................................................................................................................. 233

Accounting Conceptual Frameworks ..................................................................................... 246

Appendix ................................................................................................................................ 248

-

ix

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

It is a pleasure to acknowledge the efforts of my supervisors Professor John McKernan and

Dr Alvise Favotto for their unconditional support, encouragement and guidance throughout

the development of this thesis. I particularly thank them for their patience and intellectual

efforts that have helped me write this PhD thesis. I also thank them both for their support

and friendship over the years.

I also would like to thank both of my examiners, Professor Chandana Alawattage and

Professor Vassili Joannides de Lautour for their time and effort in reading and examining

the thesis.

-

x

DECLARATION

“I declare that, except where explicit reference is made to the contribution of others, that this

dissertation is the result of my own work and has not been submitted for any other degree at

the University of Glasgow or any other institution.”

Printed Name: _________________________

Signature: __________

Ryan TaylorRYAN C TAYLOR

-

1

CHAPTER 1 – INTRODUCTION, RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND METHOD 1.0 INTRODUCTION: ACCOUNTING AND VISION METAPHOR

“Even a rapid glance at the language we commonly use will demonstrate the ubiquity

of visual metaphors. If we actively focus our attention on them, vigilantly keeping

an eye out for those deeply embedded as well as those on the surface, we can gain an

illuminating insight into the complex mirroring of perception and language.”

(Jay, 1993, p. 1)

A trope is probably the easiest way to open this thesis. Accounting is like looking through a

windowpane onto a world. The world exists outside awaiting representation. Accounting

functions as a glassy substance, one that reflects the features of a socially produced world.

Where accounting concepts are modelled on or reflect real financial facts, accounting

modelling is lens-like. Where accounting offers the correct amount of clarity for a user of

accounting information to see what is going on, accounting rules aim to allow sufficient light

to pass through, constructing an accurate image of the corporation.

Vision is an important metaphor for accounting. Ruth Hines explained this window analogy

in financial accounting as the “common sense attitude”. One that “depends on the taken-for-

granted assumption that perceptions give direct access to objects and events” (Hines, 1991,

p. 317). Accounting concepts offer accurate descriptions of socially produced real world

events. Accounting functions similar to literal, scientific, representations, where “normal” –

propositionally accurate literal language – should be the basis of its rules. Accounting should

provide accurate, maximally informative images of corporate activity.

The aim of the thesis seeks examination of vision metaphor in the context of “normal”

accounting regulatory discourse (accounting conceptual frameworks). The aim is to see

whether vision metaphors evolve over time, and more precisely, what they mean in

connection to financial accounting objectivity and knowledge. It is also to see whether

accounting concepts seek to re-present reality in similarly metaphorical way, where

accounting rules represent or map ontologically subjective socially created phenomena. It is

the motivation of the thesis to study the evolution of vision metaphors in order to analyze

how accounting regulation functions. The thesis attempts to understand whether a scientific,

visual conception of knowledge still holds. By corresponding its rules to real economic

phenomena, accounting regulation, that is, accounting conceptual frameworks, have

-

2

conformed to a modernist conception of knowledge and objectivity. Vision is herein

understood in terms of the following: accounting rules build an accurate picture of economic

events (Mouck, 2004)1. The thesis’ hunch is that the visual potential of accounting and the

processes of transparency, light, clarity – accounting rules - slowly begin to de-construct.

Therefore, the importance of this study is to understand how this vision is understood as

following a trajectory from the modern to a postmodern; that is deeply part of the way we

socially/collectively experience our world. It is presumed from the outset, that the world has

an impact on bodies, cognition and conceptual structures (Lakoff, 1987, Lakoff and Johnson,

1999, Clark, 1997). And so, it is assumed that vision, this ideal of looking through the glass

of a financial report, can no longer be automatically presumed, over time. With critical

accounting scholars demonstrating the inability of accounting to build accurate

representations or images of organizations, vision metaphors are studied longitudinally to

analyze if change has occurred. And with that, what kind of conception of accounting

knowledge and objectivity there is; if indeed there is one.

An important point to stress is that vision is a significant underlying metaphor within the

structure of epistemology (Rorty, 1979, Levin, 1994, Jay, 1994). For the thesis, vision

functions in a less than overt, visible, obvious, even conscious way. Vision is hidden in the

structuring of everyday language and thought (Lakoff and Johnson, 1980, 1999). In other

words, vision is submerged within “normal” presumed literal language (Sweetser, 1990,

Leder, 1994, Gibbs, 2017). More specifically, vision is not so easily recognizable on the

exterior of language, remaining automatic and unconscious. Thus, studying vision metaphor,

not as an overt metaphor that is easily recognizable, but as a buried submerged part of the

construction of ordinary language, can demonstrate the development of evolutionary

meaning of objective knowledge within accounting regulation. And this is the thesis’s focus:

to study the nuanced way in which vision metaphor appears in accounting discourse, and

how vision conceptualizes ideas about what objective accounting knowledge is.

1 This is the view Mouck (2004, p. 533) expresses, “In this sense, the rules of financial accounting have much in common with the rules of painting as promulgated by the Renaissance writer Leon Battista Alberti. As pointed out by Crosby (1997, pp. 183–186), the perspectivist approach to painting (also referred to as construzione legittima) combined the ancient Greek theory of optics with Ptolemy’s approach to cartography (i.e. the use of a gridwork of coordinates, now familiar to us as lines of longitude and latitude) to produce what came to be known as ‘‘realistic’’ pictures of the visual world.”

-

3

1.1 THESIS’ FOCUS: VISION METAPHOR

The thesis began by considering how vision functions in accounting regulation. Vision, it is

assumed, is a deeply submerged conceptual metaphor for objective knowledge (See Gibbs,

2017). Hannah Arendt observed that “from the very outset, thinking has been thought of in

terms of seeing” (1978, p. 110). And so, the thesis assumes that a knower relates to the

known world through vision as conventional/normal - the way knowledge is normally done.

The subject gets outside to the assumed features of the real thing, attempting to reflect the

core, qualitative features of the other object. And to know the other well assumes that there

are features to be known. The subject’s vision conforms to the feature of object’s qualities,

where a passive viewing distance from that object provides factual, accurate re-presentations

of the intrinsic features of phenomena in the receiver’s mind. The mind functions, like a sort

of reflecting surface, a mirror where the mind is largely a passive receiver of phenomena.

Knowledge derives from the eyes looking outside onto the external social world. The idea

here is that this conception of vision alters. Vision, its frailty, demonstrates the instability in

the assuredness of accounting knowledge and objectivity.

As a consequence, the method employed in the thesis is done in such a way in order to extract

vision metaphors, so as to explore their evolution. Which is to say that the method was

informed by the view that vision is a submerged metaphor that is rooted deep within

accounting language. And is assumed to evolve in parallel with changes within ourselves

and our world, as subjects and objects reciprocally influence one another. Metaphor,

according to the thesis, derives from a deeper, body-world engagement - a causal account of

metaphor. Which develops from a more critical view of the literature, where metaphors are

assumed to derive from cultural subjects specifically, by way of naming, using rhetorical

strategies, subterfuge or exercising power in order to justify on behalf of reason. By studying

vision in the former way, as an outcome of a deeper body-world relation, vision can help us

understand the importance of the evolving meanings of objectivity and knowledge, and

reason; through an understanding of metaphor as an outcome of this reciprocal body-world

relation, rather than a subjectively imposed human strategy to enact power over entities via

linguistic authority.

Overall, Vision as Knowledge has been denigrated (Jay, 1994) from this assumed power

perspective. Vision is connected to hegemonic power and authoritative control (Levin,

1993), as the master sense of the modern era (Jay, 1988, p. 3-23). Distance, disengagement,

passivity, masculinity, voyeurism, indifference, sovereignty aggressiveness, violence et al.

-

4

are all condemnations of vision as a form of knowing that is reduced to a “single point of

view” (Jay, 1988, p.7). Similarly, the accounting literature, through taking various

postmodern, discursive, and hermeneutic positions which feature the idea of accounting as

a creative language, attempts to challenge this hegemony through this assumption of

language as reality. Where language at best is a flimsy, replaceable, dispensable, out of touch

human device, in terms of reflecting reality. By assuming vision other than a unitary, singular

concept connected with disengaged rational observation that pertains to masculine

dominance, the approach taken in the thesis has been developed differently: that vision

simply evolves. In order to convey a more nuanced understanding of the vision metaphor it

is understood that vision is part of a broader, philosophical nuanced debate that begs larger

questions about the nature of literal language, science, objectivity and knowledge in financial

accounting. A longitudinal study of vision metaphors, therefore, is adopted in order to

understand the evolutionary significance of change in the evolving development of

objectivity and knowledge or more succinctly, objective knowledge. And in order to develop

an analysis of objective, value free, scientific pursuit of knowledge in accounting conceptual

frameworks, the thesis attempts to understand the evolving nature of vision.

1.2 VISION: EXPLAINING THE METAPHOR’S EVOLVING CHARACTER

It is normally presumed that vision implies a fixed, passive, inactive, objective, even literal

representational approach towards knowing the world (See Johnson, 2007, 2017). Notions

of distance, disinterestedness, coldness, even belligerence in the approach towards knowing

another, are pervasive in thinking about objective knowledge (Levin, 1993). Ob-ject

basically means to throw out the body (Hetherington, 1999), and value the mind as a

representational instrument, that seeks a good image of the outside world as a form of

knowledge.

However, this type of vision as a modernist all seeing, all-powerful gaze cannot hold out

(Jay, 1994). That is, it is seen here that such a position is resisted from an embodied

methodological position taken in the thesis. In other words, it is demonstrated that there are

other visual regimes (Jay, 1994) that does not require an all seeing, all knowing, even literal

representation. As we move from modernity to postmodernity, vision is unable to be

generalized in terms of disinterestedness, power, the subject gaze, essences and absolute

truth. To understand vision is to understand, “how ineluctable the modality of the visual

actually is” (Jay, 1994, p.1, see also, Crary, 1990). As a result, the thesis develops an

embodied-cognitive methodological approach in order to understand the often taken for

-

5

granted understanding of vision as a metaphor that is commonly connected to the subject

position: power, dogma and disinterestedness. All themes that are argued outmoded in

relation to knowledge and objectivity today.

The research in this thesis seeks to explore vision metaphors in accounting discourse, and it

is in my view, that a study of vision would benefit an understanding of differing conceptions

of accounting knowledge and objectivity. Conceptions that can be unconnected to the view

of accounting as an abstract, passive gaze onto presence. And one which would benefit from

a further and deeper analysis of the evolution of this metaphor in an accounting linguistic

context. It is felt, to go beyond analyzing overt, rhetorical instances of metaphor studies,

vision must be understood as fluid, changing and evolving, and most importantly for the

contribution of the thesis, as a rather submerged/unconscious concept. This is not only in

order to understand the treatment of vision metaphors and the varied nuances they appear to

have in accounting regulatory language, but also for me to understand the evolutionary

nature of meaning within conceptual frameworks; especially when frameworks

communicate through vision metaphors the presented meaning of accounting objectivity and

knowledge.

Therefore, the thesis theorizing is informed by scholars who explain change in vision,

knowledge and objectivity through time. Allan Megill, a historian of philosophy, is one such

scholar who offers up an insightful explanation of change in four descriptive ways. Megill

focuses specifically on objectivity, and how the sense of its meaning has changed over time.

Megill offers four senses of objectivity: The Absolute, Disciplinary, Dialectical and

Procedural senses of objectivity. Where knowledge and objectivity connect to the hegemonic

assumptions of modernity (See Levin, 1993), conceptions of objectivity, knowledge,

subjectivity, meaning, and experience is assumed here to be multifaceted, plural and in

continuous flux. Since concepts of objectivity, linked to concepts of knowledge and vision

are assumed structural, the research attempts to extract these vision metaphors that are buried

deep throughout corpora (Lakoff and Johnson, 1999). Since vision is normally associated

with Western conceptions of knowledge as cognitivist, objectivist, value free, distant, and

passive, the research aim is not only to discover and analyze vision metaphors, but also, to

make a modest methodological contribution. That is, to develop a method for obtaining such

buried, vision metaphors within accounting text. The results from the method are given in

chapter six, to show the changing and altering nature of Vision as Objective Knowledge (See

Sweetser, 1990); and to explain variability in this Vision as Knowledge metaphor that

accounting conceptual frameworks demonstrates.

-

6

1.3 HYPOTHESIS: VISION AS A SUBMERGED METAPHOR FOR OBJECTIVE KNOWLEDGE It is hypothesized that the Vision as Knowledge metaphor, like Megill’s explanation of

objectivity, and for those who espouse ontological political views (Law and Mol, 1999, Mol,

2002, Urry, 2000, Law and Urry, 2004) retains its presence in conceptual frameworks. Yet

there is something different about what it means over time. And this is due to the way

practices relate to objects in different places and different times. That is, Vision as

Knowledge, like Megill’s varied yet interconnected explanation of objectivity, is not read off

or conceptually complete. In other words, it cannot be a fixed, definitive concept, detached

from time, circumstance and history. In other words, it evolves by a process of social change

informed through the way human beings interact or engage with and respond to, changes in

their experiences to life-worlds, which they share and come to, hopefully, reasonable

outcomes.

To expand on this view, Vision is Knowledge is metaphorical, but most importantly for the

thesis, submerged. Vision appears non-deliberately in discourse and is part of a deeper

relationship between body and world (Sweetser, 1990, Lakoff and Johnson, 1980, 1999,

Johnson, 2017, Gibbs, 2017). But it also lodged within a hegemony of Western epistemology

(Levin, 1993). And so, it is hypothesized that the modern, a-temporal, disembodied,

disconnected and hegemonic notion of “vision of modernity” (see Levin, 1993) requires a

research approach that assumes relationships exist between body and the technological

advance of the postmodern world (Lakoff and Johnson, 1999, Johnson, 2017). In other

words, vision will be responsive to body-world evolution over time (Clark, 1997, Evans and

Green, 2006), of working with others and other technologies, other than assuming a human

subject in sole, absolute control, working independently of that lived world.

Therefore, it is the view of the thesis that metaphor is an outcome of the way bodies interact

with environments (Lakoff and Johnson, 1980, Lakoff, 1987, Lakoff and Johnson, 1999).

Tropes are not so easily controllable, nor are they subjected to conscious choice: “tropes as

deliberate departures from standard usage” (Pinder and Bourgeios, 1983, p. 610). Metaphors

are normally presumed to sit comfortably on the surface of language (Deignan, 2005) to be

seen, to be directly accessible, interpretable and changeable. A common view of metaphors

is that they are novel, clear, cut and dried parts of discourse or speech that are easily

identifiable. And so, the research aims, in spite of this, to seek non-deliberate vision

metaphors.

-

7

The thesis, on the other hand, sees metaphors as an entrenched part of meaning/of language,

which arises out of a profound contact between embodied experiences and the shared world.

The view in the thesis is that metaphors are rather outcomes, where metaphors are buried

and deep in thought and language because of the bodies we have, and the worlds we share.

It is understood that by and large, vision metaphors are non-overt, and remain largely unseen

in the development of accounting regulatory discourse. And are, for this reason most

probably, underexplored in the accounting literature. The thesis views vision as one such

non-overt metaphor. One that resides deep within the presumed objectivity of accounting

regulatory discourse. As a result, this view of metaphor influences the research methods

employed in the thesis, which demonstrates a way to extract more submerged vision

metaphors from the conceptual frameworks chosen for study here.

It is in light of this that the reader may acknowledge that metaphor comprehension is a

common theme that runs centrally throughout the thesis. According to Pinder and Bourgeois

(1983), metaphor is “a creative activity, as its comprehension (Pinder and Bourgeios, 1983,

p. 608, citing Andrew Ortony, 1979). Part of that creative activity is the understanding and

re-understanding of metaphor that metaphor invites. And in particular, drawing attention to

the imbedded metaphorical structure of what is presumed non-metaphorical/literal

accounting regulatory discourse: the accounting conceptual framework.

1.4 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORKS AS THE EMPIRICAL SITE

“The conventional view holds that professional accountant’s role is to report

factually about the entity’s economic and financial transactions and economic events

in a neutral, objective fashion, as reflected in the decision usefulness conceptual

framework that requires accounting information to be not only useful of relevance to

users, but also be reliable, veritable and representationally faithful”

(Macintosh, 2002, p. 38)

Financial accounting conceptual frameworks are the basic building blocks of standard

setting, representing what may be called, accounting knowledge (Hines, 1991, 1992).

Conceptual frameworks help assist accounting standard setters develop new rules, concepts

and standards of practice, helping to settle conceptual ambiguity. Accounting knowledge of

the external world can be understood via rules that communicate real world corporate

phenomena. Conceptual frameworks are not only useful to accountants who are able to

communicate to financial statement users, conceptual frameworks also guide the

-

8

development of future standard setting. And in order to gain knowledge of possible

economic outcomes, accounting rules are developing. The conceptual framework is open-

ended; hence the word project seems to be altogether collocated with conceptual

frameworks2. As Hines wrote, conceptual frameworks are sites in which a determination is

made about what counts as knowledge, and what sustains the social world of capitalism is

financial accounting:

“The meaning and significance of Conceptual framework projects is not so much

functional and technical, ‘but rather social and cultural. Financial accounting

practices are implicated in the construction and reproduction of the social world’ and

it would seem to follow, as suggested by several authors that CF projects similarly

play a part in the process of the social construction of reality”

(Hines, 1991, p, 313)

The conceptual framework project, according to Hines, is a crucial document for one

important reason. Accounting knowledge is constituted through the conceptual framework

project. Hines proposes that a conceptual framework represents a body of technical

knowledge that also reproduces current lived, social reality.

“In the social sciences, the undermining of realism has been even more complete. A

variety of authors have shown that social reality is refIexively constituted by

accounts of reality, and that the decisions and actions of social agents based on these

accounts, constructs, maintains and reproduces social reality."

(Hines, 1991, p. 317)

1.4.1 TYPES OF FRAMEWORKS

There have of course been a number of framework projects at the national and international

level. And these national and international efforts are presently ongoing. In the US, Canada

and Australia for example, there have been conceptual frameworks since the 1980s. In the

2 It is presumed that accounting conceptual frameworks are still affected by a kind of powerful system of metaphysics, that maintains faith in the market, the capitalist system and its technologies that frameworks sustain. Overall, the thesis attempt is to understand this trajectory in knowledge through exploring vision metaphors. What certain insights vision metaphors potentially inform regarding the changing landscape of conceptual frameworks’ and the varied conceptions of knowledge, particularly as accounting enters this particular era of capitalism.

-

9

United Kingdom, there was the Statement of Principles, published in December 1999. There

have also been a number of international efforts, such as the International Standard

Committee’s initial framework in 1989.

In this thesis, it was decided to begin with Financial Accounting Standard Board’s initial

efforts that began in 1978. And then finalize the analysis with the most recent international

exposure draft, published in May 2015. At the time of writing, the International Accounting

Standards Board (IASB) has yet to finish its most recent project, which the board expects to

complete by early (provisionally March) 2018.

Thus, the analysis focuses on the following frameworks: Financial Accounting Standards

Board 1978 SFAC No.1 Objectives of Financial Reporting, the SFAC No. 2, Qualitative

Characteristics of Accounting Information (1980), the SFAC No. 5 Recognition and

Measurement in Financial Statements (1984) the SFAC No. 6, Elements of Financial

Statement (1985), the International Accounting Standards committee’s (IASB 3 ) 1989

Framework for the Presentation of Financial Statements, Accounting Standards Board 1999

Statement of Principles, and The 2010 International Accounting Standards Board's

Conceptual Framework for Financial Reporting. The IASB's Exposure Draft published on

the 28th of May 2015 is also analyzed as a proxy for the 2018 framework. The aim is to

explore these conceptual frameworks, and identify the vision metaphors that appear in each

of them, categorize them, and explore the categorical transition over time.

1.5 RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND AIMS

The research questions are linked to metaphorical evolution in the Vision is Knowledge. This

metaphor is a submerged, assumed conceptual metaphor4. How this could be studied in a

longitudinal study of accounting conceptual framework’s metaphorical content influences

the research questions. The questions are twofold:

Question 1: Are there differences in the type of categories of vision metaphors that

appear in conceptual frameworks in the period from FASB 1978 to IASB 2015

Exposure Draft. What are these different types?

3 The International Standards Committee is now Board, and (IASB) is referred to throughout.

4 A conceptual metaphor refers to the understanding of one idea (concept) in terms of another.

-

10

Thus, could accounting Vision as Knowledge be a transformative conceptual metaphor in

accounting conceptual frameworks? Firstly, by identifying vision metaphors, and

categorizing them. From this, a further exploratory research question could be determined:

Question 2: What is the evolution in the patterns/trends in these types of vision

metaphors that appear in conceptual frameworks inform about the way conceptual

frameworks conceptualize knowledge?

To answer this question, an attempt to qualitatively analyze in some detail the concordance5

lines of the vision metaphors that are found. That is, to analyze also the context, words,

clauses and phrases that are in close proximity to the vision metaphor. This was in order to

investigate differences in how knowledge is conceptualized in conceptual frameworks

periodically.

1.6 RESEARCH QUESTIONS’ IMPORTANCE FOR CRITICAL ACCOUNTING

The accounting literature focuses on the overt, almost accessible notion of language. Other

literature focuses on more obvious metaphors. Amernic and Craig (2006), exploring CEO

speech, interestingly sheds light on the rhetoric of business discourse (see also Amernic and

Craig, 2009, Amernic, Craig and Tourish, 2007). These research findings provide insight

into the language of business at an overt level. The submerged conceptual metaphorical

language is not the type of language that the accounting research focuses on. It is understood

here that certain other automatic or unconscious metaphorical language is underexplored,

within the context of accounting discourse. Especially discourse that does not entirely

overflow with rhetorical language (conceptual frameworks). It appears that the depth to

which metaphors are submerged in our everyday language is not well understood in financial

accounting research.

The employed method in the thesis attempts to get to these deeper, submerged conceptual

metaphors. Metaphors that are not so immediately perceived [explained in the methodology

and methods chapter (see chapter 5)], but are largely automatically applied in ‘normal’

everyday descriptive language. It is hoped that the method can help draw out many of the

submerged metaphorical visual language that reside in the apparently neutral and value free,

5 A concordance is the surrounding context of the word, in order to understand its meaning in situ.

-

11

non-metaphorical language of accounting conceptual frameworks: language that is assumed

devoid of creatively used overt metaphors6.

This method assumes that metaphorical language is not entirely accessible on first

inspection. That a lot of our language is deeply metaphorical, whose derivation is from a

thousand-year-old history, is generally forgotten. Language is composed of many non-

deliberate metaphors that point to physical action, the body, and how the body encounters

another, physically. The thesis attempts to understand what these deeply, taken for granted

vision metaphors are. How they appear, and why they have undergone change in the period

is examined in this thesis. The method used here on accounting conceptual frameworks is

considered appropriate given accounting frameworks are closer to literal, legal

documentation. Accounting conceptual frameworks involve many assumptions about literal,

objective or neutral language. But in fact, like other legal discourse, evolves, in the way

language has been evolving from a history that spans hundreds if not thousands of years7.

1.7 METHOD: A CORPUS BASED CONTENT ANALYSIS

In this section, it is now explained what a corpus based content analysis is. A corpus based

content analysis is an exploratory research method that has been mainly used by journalists

and communication researchers in order to investigate textual data (newspapers, books,

articles and so on). A corpus analysis is a way of tracking change. It is a way of revealing

certain biases, prejudices, and taken-for-granted assumptions, inter alia, within a text, or

even, an archive of texts. In a sense, the analyst desires to reveal underlying questions from

the linguistic data studied. The analyst wants to understand the ways in which text(s) could

be categorized. That is, how different words, phrases, or lexical units fall into broader

categorizations, mainly to reveal themes, subtexts, biases, or ideological thought within

texts. The content analyst desires to select targeted texts and reveal the human, embodied

and subjective indicators that reside within the object of study.

The corpus based content analysis has been used for many purposes, some of which are

shown below (adapted from Weber, 1990, p. 9). These are:

• To reflect cultural patterns, institutions, or societies.

6 Such metaphors are sometimes, “one-off metaphors” (Lakoff, 1993, p. 229).

7 The English courts use the ‘literal rule’ or ‘plain meaning rule’ where statutes are to be interpreted. Judges may use a dictionary in order to give words ordinary meaning.

-

12

• To reveal the focus of individual, group, institutional, or societal attention.

• To describe trends in communication content.

The corpus analyst tries to pick out different units/words and see how these words fit within

a particular category. For example, words such as weapons, firearms, bombing, missiles,

conscription, detente, battalion, and so on, may belong to a semantic category, "warfare".

Thus, the analyst attempts to extract words with similar meanings and group them together

under one central conceptual category. And this can be done either by classifying words in

accordance to precise meaning (synonyms) or searching for words with similar connotative

associations.

In sum, the analyst tries to understand the words, phrases or other units of text with reference

to some common theme. This is done by carefully extracting words, and attempting to make

sense of those words, phrases, lexical units from patterns generated. Ultimately, the analyst

seeks to make sense of the linguistic data found, deciphering meaning and drawing

inferences from what is studied. The aim is to reduce data to the categories of a particular

frame, which then allows the analyst to break down further these linguistic data into smaller

coding (categorizing) frames. The method in the thesis is best observed in steps, which is

described in the next section.

1.8 STEP 1 - IDENTIFYING VISION METAPHORS

Vision metaphors are identified, as a first step, using a web-based corpus analysis software

W-Matrix. W-Matrix provides word frequencies for each and every word used in the

frameworks studied. From this, vision words could be isolated from the frameworks using

an etymological analysis. The word’s etymology is used in order to identify whether the

word had some visual relationship to each word that appeared in the conceptual framework.

In connection with our methodology, it is suggested that there is a sort of visual quality to

the language in conceptual frameworks. This was a first step.

Thus, another, look for the primitive origin of the metaphor is performed in order to identify

how much or how little of the active or inactive body is present in the word’s etymological

root. The Indo-European root or Proto language (basically, the word’s morpheme) is used in

order to identify how much of the body is rooted in the vision metaphors studied. The

approach is to look for vision metaphors, as a first step. An etymological search engine is

used to identify whether the word had a connotative/semantic relationship with vision.

Second, the vision word’s indo European root (primitive root) is used in order to determine

-

13

how much of bodily activity was present in the metaphor, Vision is Knowledge. For our

methodology, from a non-constructivist perspective, vision is normally associated with

disengagement or inactivity. It is associated with a passive, sedentary stillness, that of a

mirroring mind that implies little activity, and more withdrawal. However, it is observed that

there are other active vision metaphors. This is where the word’s Indo-European etymology

demonstrates the physical, metaphorical genesis of our modern vision metaphor(s). And this

indicates something else about Vision as Knowledge. That is perhaps indicative of move

away from such simply passive, withdrawn metaphors of vision. Therefore, the aim was to

isolate these types of metaphors and examine them over time. In step two, these are

categorized in two ways, which is explained briefly in next short section.

1.8.1 STEP 2 - CATEGORIZING VISION METAPHORS

Once the first stage identification is complete, these metaphors are then categorized into two

main groups. The two groups here are first deliberate vision metaphors and second

submerged (non-deliberate) vision metaphors, the latter using the vision metaphor’s Proto

Indo European or language root to analyze the extent to which the body resides in vision.

Once categorized, these are studied longitudinally in order to assess the evolution in vision

metaphor. To state briefly, deliberate metaphors, which will be explained briefly in the next

section, do not appear frequently in accounting conceptual frameworks as most frameworks

tend to avoid deliberate metaphorical language. The main focus on the thesis is on

submerged vision metaphors.

1.8.1.2 DELIBERATE VISION METAPHORS

Deliberate categories are identified as a first step. The main aim of the thesis, however, is on

the development of submerged vision metaphors, whose change is largely under

acknowledged. To make these a little clearer, deliberate metaphors are generally creative,

poetic, or imaginative, metaphors. “Juliet is the Sun” in Act 2, Scene 2 of Shakespeare’s

Romeo and Juliet is a typical example. Deliberate metaphors are those metaphors that are

associated with creativity, usually found in poetry or fiction. They are normally thought of

as being quite clear metaphors, in that, they can be more easily isolated from the text. The

accounting literature, it is argued, seeks to isolate deliberate or consciously used metaphors.

Metaphors that sit, largely, on the surface of language (Deignan, 2005). The vision metaphor

understood in the thesis connects with another view of understanding metaphor in

accounting conceptual frameworks.

-

14

1.8.1.3 SUBMERGED (NON-DELIBERATE) VISION METAPHORS

Submerged vision metaphors are those metaphors that run through our language but are

unrecognizable or barely recognizable as metaphors. That is, they appear quite literal,

automatic or natural. For example, such statements, such as “I see what you mean” or “There

are some good insights” or “your view is short-sighted”, are metaphorical but have the

function of appearing non-obvious. But only through deeper inspection can they be brought

to the surface, into the domain of reason.

Submerged metaphors evidence a conceptual metaphor: Vision as objective knowledge.

According to Lakoff and Johnson, the conception of objectivity and knowledge is privileged

in Western culture through a metaphor of embodied perception: vision. Objective knowledge

results, according to Lakoff and Johnson, when the body views or experiences the world

from a distance. Intellectual distance, reading and writing, is the route to true, transparent

knowledge, and are part of the mental processes or activities that determines knowledge. The

body distances itself from engagement with other objects in order to know them, requiring

characteristics of stillness or the gaze to deliver knowledge. The body is away from the

world, physically. Vision is a metaphor that is submerged in thinking about knowledge,

representing what is considered objective, neutral and value free knowledge.

The thesis demonstrates that vision metaphors can be categorized into two specific ways. It

is recognized that there are two submerged vision metaphor categories. Vision metaphors

are either associated with the activity of body (the eye is active) or associated with the

inactivity of the body (associated more with the mind than with the human body). It was felt

it would be interesting to study the evolution of these metaphors in this context of accounting

conceptual frameworks. This is because inactivity has to do with passivity and spectatorship

in looking through the eyes; where the object is re-presented in the mind. The other has to

do with embodied sight (See Jay, 1994, p. 150) in that vision connects with the moving body

here; where the body sees with the eyes. The eye, like the body, is active, perceptive in

determining one’s degree of knowledge. Quite significantly for financial accounting

knowledge and objectivity, is the presence of such inactivity, the “mental mirroring of an

external reality” (Johnson, 2017, p. 70) or activity (the physical, moving body), where

“cognition is action” (Johnson, 2017, p 70). In terms of whether seeing is active or inactive

(disembodied) and what this means, would most logically determine what kind of visual,

objective knowledge conceptual frameworks seem to be aiming at.

-

15

It is found (see chapter 6), that there were more active submerged vision metaphors. And

that this evidenced a more embodied, intersubjective and perceptive sort of construction of

what objective knowledge is, over time. This conception attributes activities, such as cutting,

moving or observing, to vision. Inactive metaphors deal with mainly academic,

philosophical or intellectual thinking, the mind over the body. That is, they deal with

knowing or epistemology (including words like recognition and diagnosis), existing or

ontology (representation and presentation), and observation (seeing or vision). These were

all tracked and identified for evolving trends over time. The method of categorization can be

summarized as follows:

• Step 1 – Identify for vision metaphors using W-Matrix.

• Step 2 = Discover deliberate vision metaphors.

• Step 3 = Discover submerged vision metaphors (the thesis’s main focus).

• Step 4 = Categorize these metaphors into two categories, using the word’s Indo-

European root, in relation to the following:

a) more activity of the body (root pertains to cutting, grasping, moving, et al)

b) more inactivity of the body (root pertains to knowing, existing and observing)

• Step 4 – Split these into two separate categories and study longitudinally.

1.8.2 STEP 3 - BASIC TRENDS AND PATTERNS: CONCORDANCE ANALYSIS AND CLOSE READING

After separating the submerged vision metaphors into these two categories of active and

inactive, it was considered useful also to look more deeply into concordances (surrounding

words or context of the metaphor) in order to see within the context of the conceptual

frameworks, whether the conceptualization of vision could be understood further by

examining the metaphor’s verbal context. To take look a more in-depth look into what

conceptual frameworks were mentioning, to understand vision more, an investigation into

the surrounding concordances was linked to the study of individual vision metaphors.

Additionally, it was felt that a slightly closer reading could be achieved in order to analyze

Vision as Knowledge. It is identified that going more deeply into the frameworks context

was useful. This was because the written context elucidated further some of the individual

metaphors that were found.

-

16

1.9 THESIS LAYOUT

The main thesis is split into seven chapters, which includes this introductory chapter, a

review of the literature (chapter 2), a theoretical framework chapter (chapter 3), an overview

of the conceptual frameworks studied in the thesis (chapter 4), methods and methodology

(chapter 5), results (chapter 6) and a conclusion chapter (chapter 7).

1.9.1 CHAPTER 2 - LITERATURE REVIEW

In chapter two, a review of the literature is provided. In particular, the focus is on some of

the ways that the accounting literature focuses on a broader vision metaphor is reviewed.

The literature explains that accounting theory has challenged the objectivist, positivistic and

neutralist image of accounting policy making. That accounting effectively reflects economic

objects and events well by adopting a distant, disembodied, and indifferent approach towards

the world in order to know it is still upheld. And so, knowledge is only possible through a

treatment of the world in a specifically reductive or fetishistic sense. The critical accounting

literature challenges the conventional view that financial accounting is a passive activity;

one that merely mirrors financial reality. They highlight that the aim of accounting is to

produce other, good images of corporate realities. Which, overall, financial accounting, now

finds difficulty in doing.

Some of the initial thinking is that inspired by David Solomons, who drafted the qualitative

characteristics concepts statement 2. Solomons initially developed, what is known as, a

“neutralist” position in the accounting literature and is used as a starting point for the

literature review. From this, other significant, critical papers are analyzed. Publications that

have challenged this “common sense” view proposed by Solomons, whose metaphors appear

in the FASB SFAC No. 2 document, are outlined in this chapter. It is observed that such

literature focuses on the postmodern, structural, post-structural, and other hermeneutic

approaches, in order to advance a somewhat less than straightforward view of accounting.

This view is simply that a good eye on the way organizations function is a faulty position. It

is observed that these ideas are extremely important movements nonetheless. They are

alternatives that reflect a period of anxiety over accounting’s descriptive objectivity.

Financial accounting claims, regarding accounting knowledge as vision, is challenged quite

openly. More straightforwardly, it is suggested these papers focus on the importance of

accounting as a language game; one that supports the development of accounting concepts

-

17

that are far from objective, literal, or value neutral. Financial accounting is not a visual

medium that expands the viability and visibility of financial reality. Accounting is a mere

language that is assumed to reflect inherent economic features; features that are made by the

presupposed, and rather shared aims, of wealth maximizing behavior. This metaphor of

vision is the notion that language reflects some inherent property or feature of others, and

becomes difficult to sustain and is open to refutation. It is argued that as the momentum for

capitalism escapes human access, Vision, as a metaphor for knowledge, is challenged over

time in the accounting literature. The aim of the literature review overall conveys the anti-

visual and anti-realist direction the literature expounds, and the corresponding difficulties

that arise from modelling financial reality with accounting rules.

1.9.3 CHAPTER 3 – THEORETICAL DISCUSSION

Chapter three gives some theoretical background to the thesis. Overall it seeks to explain the

change in vision metaphor from modernity to postmodernity, through historians,

philosophers and art criticism. This discussion centres around vision and its deconstruction,

in our postmodern era. The idea of Vision as Mind, disconnected from a body that tends to

impede the progress of objective knowledge, is understood as part of accounting’s

conception of what objective knowledge appears to be, at least in earlier conceptual

frameworks. The idea of vision as an evolving concept is important to the idea of different

other visual possibilities. Which is linked in the thesis to scholars who work in various areas

of philosophy, art criticism, sociology and history. It is discovered that the eye is understood

in terms of the passivity of an acute mind/intellect, associated with reflection metaphors,

where mirroring and image building qualities are built in. The move away from this

conception of vision vis-a-vis passivity arises from a movement towards newer

understandings of representation away from the purely static form. That is, that the mind is

embodied and requires an embodied cognitive system that is open to mutation. Not only to

understand, but in order to gain knowledge must there be a capacity for evolutionary

transition. This thinking forces a new way of thinking about subjectivity, no longer as an eye

that is of the mind, but an eye that is attached to a physical, moving body that is subjected to

material forces.

1.9.4 CHAPTER 4 - CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK OVERVIEW

In the next chapter, a basic background to conceptual frameworks that is studied in the thesis

is provided. The frameworks analyzed in the thesis start from 1978 and finish with the 2015

-

18

exposure draft. It is recognized on first reading that conceptual frameworks are similarly

structured. Conceptual frameworks share much of the same content. The IASB 1989 and

IASB 2010 appear to be very similar in nature, for instance. The earlier frameworks,

particularly FASB SFAC no. 2 Qualitative Characteristics have a few deliberately used

representationalist metaphors that compare accounting reports with representational tools,

such as maps or similar projection devices. This is mainly a consequence of David

Solomons’ influence (Zeff, 1999, p.110). It is recognized that the absence of such metaphors

may indicate that accounting conceptual frameworks intentionally remove such deliberate

metaphors arising from predilection, which is unsurprising. Those metaphors that do not fit

with the more representational, direct or literal straightforward language that later

frameworks may be aiming for are no longer included but may serve as part of the conceptual

framework narrative. Nevertheless, this chapter is brief overview of the conceptual

framework period that is analyzed in the thesis.

1.9.5 CHAPTER 5 - METHODOLOGY AND METHOD8 1.9.5.1 METHODOLOGY In this chapter, Lakoff and Johnson’s methodology is used to justify a causal account of

metaphor in accounting. Their theory explains that the body (vision) metaphor for

conceptualizing other, more abstract experiences (knowledge). Lakoff and Johnson’s

theorizing is applied in the thesis in order to argue that concepts are cultural, and depend on

having a body and a shared world. And that conceptual schemes are subject to semantic

changes as the body encounters/experiences the world in radically new ways. According to

Lakoff and Johnson, the way bodies interact with their environments9 influences the types

of meanings we have, the ones we share which, may or may not, have value. Therefore, as a

consequence, Lakoff and Johnson point out that mirroring and reflection metaphors are at

best consequential. They arise because of the way the lived subject withdraws from physical

activity and simply looks, and that this way of looking is inherent to the foundation of

knowledge in the Western Philosophy (See Johnson, 2017). Since the body withdraws from

doing things and simply looks at things, the way that the body then encounters the world is

withdrawn, distant, and passive. That as a consequence generates a kind of disembodied

form of knowledge that privileges a representational knowledge; one that yields the

8 The methodology and method section are included in one chapter.

9 The thesis adopts the term environment for convenience only.

-

19

associated metaphors of mirroring, reflection and representational accuracy formed in the

cognitive system. To put it in the way Andy Clark (2003, 2008), philosopher and proponent

of the extended mind hypothesis, thinks about brain, body and world, there is a dynamic

interplay between the evolving technologically advancing world, and the way the sensing

body responds and interacts in real time with that world. And it is the world that affects the

cognitive processing of human subjects. This happens by way of triadic relation in which the

mind is not linked to the brain alone, but composes the relation between brain, the non-neural

body and the external environment. In crude terms, it might be said that:

World evolves = body evolves = mind evolves

(Clark, 1997)10

Therefore, Lakoff and Johnson’s theories on embodied meaning is not only used to

categorize our vision metaphors, but also to identify them. Lakoff and Johnson contend that

that vision helps to conceptualize other, perhaps abstract experiences, like knowledge. Thus,

Lakoff and Johnson’s thoughts on embodied cognition reveals that the body, its location and

surrounding environment, shapes cognition. And that the type of body we have, coupled with

the type of environment in which that body is embedded, has a significant influence on

language. Such a position holds that the world, body, and concept, or metaphor, are tightly

bound together, and cannot be so readily discarded. So much so that the metaphor is a deeply

ingrained or constitutive part of thought that is unnoticed in accounting discourse. It is

Lakoff and Johnson’s argument, therefore, that metaphor structures thinking on a deeper

level, and that thinking is based on the types of bodies we inhabit, the types of environments

we share, and the interconnectedness between the body and environments that engender the

metaphors.

1.9.5.2 - METHOD

As mentioned, W-Matrix (a web-based corpus analysis and comparison tool) is used in order

to isolate potential metaphor candidates. An initial etymological analysis was done. This was

performed in order to initially assess whether the candidate word had some connotative or

denotative connection to vision. That is, the word had/had not a certain visuality about it. If

10 In Clark’s (1997) book, Being There, Putting Brain, Body and World Together Again. A similar view is held in The Embodied Mind by Varela, Thompson and Rosch (1991: xx), in which they define cognition as “the representation of a world that is independent of our perceptual and cognitive capacities by a cognitive system that exists independent of the world.”

-

20

it did, the word was included for further investigation. According to Lakoff and Johnson’s

methodology, knowledge is more closely associated with a distinct lack of bodily activity;

usually associated with idle, passive viewing. And also indicates that primacy may be given

to representational modes of thought which pertains to image, vision and the mind (See

Simpson, 2017). From there a method was found in order to locate idle, sedentary features

in the metaphor, and, also, other types of active vision metaphors that reveal whether the eye

is inactive and fitting the archetype of Western thought or whether the eye is doing

something else. This was done through using the word’s Proto-Indo European Root. This

helped to isolate inactivity or activity in the vision metaphor. Vision metaphors were

explored over time in order to identify change in the conceptualization of accounting

knowledge and what this might mean. From this, two categories were observed: deliberate

and submerged vision metaphors, which were explored over time.

1.9.6 CHAPTER 6 - RESULTS

In these frameworks, there are deliberate vision metaphors and there are active (body) and

inactive (mind) submerged vision metaphors. And we track these longitudinally. What is

discovered is that the starting point is FASB which employs deliberate metaphors, basically

intentionally used metaphors coming from David Solomons in the early Financial

Accounting Standards Board. These intentional metaphors are considered briefly because

they are so few in number. The focus of the thesis is on submerged (non-deliberate) vision

metaphors, and these are examined in more detail in this chapter. Over time, more submerged

metaphors are identified. These metaphors provide evidence of a more active vision (related

to the body), which signifies something different about vision as connected to the mind, in

opposition to the body. This is explored this in more detail in chapter six. It is basically

discovered that Conceptual Frameworks move away from this knowledge conceptualized in

terms of the representational mind (Vision as Mind/disembodied), and that there is more

evidence of a more active, non-representational vision that resides in conceptual frameworks

over time, knowledge is the body (Vision as Body/embodied).

1.9.7 CHAPTER 7 - THESIS CONCLUSION

Chapter seven is the conclusion chapter. The chapter is divided into two parts. The first part

provides an overview of how the research questions have been addressed in the thesis, what

the empirical findings suggest, and the implications for financial accounting as a result. The

second part demonstrates the ontological political implications that arise from conceptual

-

21

frameworks in terms of the findings of the thesis, and what this may mean for financial

accounting more generally.

-

22

CHAPTER 2 - LITERATURE REVIEW 2.0 INTRODUCTION

"Put in an accounting context, a post-structural11 perspective rules out the contention

that accounting information and reports should, or can, reflect, some real, out-there

reality. It sees persistent calls for transparency as futile and so irrelevant."

(Macintosh, 2000, p. 119)

As a reminder, the basic purpose of the thesis is to understand the evolving status of

accounting as objective knowledge through vision metaphors that are submerged - that are

subconsciously used - within accounting conceptual frameworks. Through a corpus analysis