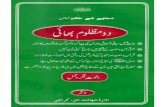

NECESSITY AND TRUTH A: Dou~le W...

Transcript of NECESSITY AND TRUTH A: Dou~le W...

(c) 1965, Times NewspapersDoc ref: TLS-1965-0114 Date: January 14, 1965

26

A : Dou~le First

in Modern ,Languages

It is not often that. within just avera month , two maior prixes are awarded to translators of books published by the same

: firm. This distinction has lu st befallen two · of Seeker & Warbur,'s translators, An,us

Davidson 's John Florio prize for his translation of Moravia's Morc Romon Toles bein, (ollowed closely by the Swedish Academy's award of its Gold Meda~_never before

· won by a translator- to Michael Meyer for the first volume of what will be a complete neW version of Strindber,'s

· plays.

Otherdistina uished tu.nslatorswho have worked with Seeker & Warburg include : Archibald Co'quhoun. P.a.trick Leigh Fermor. Xan Field ing. Grace Frick, Peter Fryer. Edward Hyams, Donald Keene. H. T. Lowe-Porter, Enid Hcl '!od, David Maganhack, Ralph Manheim. Peter Mayne, Willa and Ed ..... ;n Muir. Just in O'Brien. G. D. Painter, A, J. Pornerans, Raymond Postgate. Hen ry Reed , Roger Senhouse, Antonia White, Peter WIles, Eithne Wilkins and Ernst Kaiser, and Beryl de Zoete. Let us honour these and other practitioners of an art which ail too often lOCS unsung,

And the authors whom they translate 1 Here are 01 few:

French Italian Bni" Moravia Boulle Svevo

Chevallier Japanese Colette Hishima Gide Tanizaki

Peyrefitt. RUSSian Rey Eisenstein

Yourcenar Leskov German Sfxlnish Grass Garcia Lorca Kalka Swedish Mann Bergman Musil Strindberg Greek Yiddish

Kazantukis Singer

All these authors arc publi:hed by

Seeker & Warburg , (For some of our English and

American authors see p. 21)

A spirally bound booklet containIng monthly charts of the sky at nigh t for 1965, together with details of the phases of the moon and notes on the planets. It has been specially compiled by the Astronomical Correspondent of

THE.·_TIMES 4s. Od. (rom booksellers, or di rect (rom Special Publications, The Times, London, E,C.~. (postage 6d. extra)

THE TIMES 'LITERARY SUPPLEME N T THURSD.AY JANUARY 14 1965

NECESSITY AND TRUTH u s what is ralher an explanatory comment-ary.tban a translation, a course it is difficult to approve. But the fact that it is noW not so difficult to explain such phrases marks sortie change in phHosophy. We are noWadays in some ways closer to the ancients and the medievals than we are to, say, Kant and J:legel. .There are doubtless man y pomts which go together to fo rm ,this situation: but if the reviewer were challenged to name .what mos! sirikes him he would point to the total eclipse in recent philosoph'y of l·he not jon of Ihe give" and .the manner "of the current gradual redepartu re from atomistic conceptions, Ask!d What was gi yeJl . a pres~nt-day Englis·h speaking phi losopher ' would be very

W HAT IS KNOWN must be true; hence it readily appears that only the necessarily

true can be k.nown. This is probably one root of the G reek conception of knowledge as of (he changelessly true. Nowadays an undergraduate ea rly learns to criticize the passase f rom .. What is known is necessarily true" to .. Only tbe necessarily true is known"; the former is correct only in the sense that if something is not {rue then my certainty that it is I-he case is - necessarily- not knowledge; and from Ihis noth in g fonaws placing any restriction on the objects of knowledge,

One is likely to lea rn this criticism in connex;on with Plato's doctrmc tha t on·ly supra-sensible forms were objects of knowledge properly socalled. and ArilVtotle's doctrine tha t the sphere of knowledge was only: the kind of thing t·hat cannot be oth~rwisc. The appearance of the tina vo lumes·· ·of a sel of sixty-()f a new translalion of the Summa Tlu'oIOKiaL' (sometimes called the Summa Tlle%{:ica ) of SI. Thomas Aquinas prompts one 10 ponder 51. Thomas's attitude to this question.

We find it pre:;cntcd in him in a heightened form: must not GVtI'J.· knowledge be on ly of what is necessari ly true '! - so that eilher there is no cont ingency about the fut ure. or Goo does not know ali that is to come (la, 14. 13), St. Thomas is indeed partly caugh t in the trap of argument with which we op: ncd, He e.scape .~ from it wit hou t fully realizin·g th·is- by an appeal to the distinction between necC'ssity fit' n' and necessity de didO. as we did. For that is what our a rgument was. thou gh the point may be obscur<.!d by the fact that the r<'.f in question. the things tha t are known. arc th~m~~l ves diclil. such as /fUll soum(-so will II';" Ihe lI<,xt <,/<,dioll (known on ly to God) or ,"m I s"all "ol find IIIlll pot of ('(~Dt!e til my I'Ihow '00 1101 10 drink (known well to mel. The compatibility between the cunl :ngency (nun-necessity) of these k n~)\vn r(' .\ and the necessity of the dil'111111 .. What is known is Irue " is the right wa y ulil of t:he trap .. , . But one goe.;; straight back inllo it li ke th is: nlU 'it not Ihe I{w( 0/ '11<, knowIe'tlll :' of such a cont ingency itseJf be equally conl ing!!nl " That is to sav. must it not always be capab le of turning out fal .;e. tha t such-and-su(.'h a way for the fu tu re to turn o ut i,~ known to h:= th:: way it will turn oul ? For. being con.tingent, this III(I), nol happen.

Man y mighl want to accep t Ihis so far as concerns human knowledge. and so hold Ih~H therc is after all no escape from the trap. SL Thomas was Slopped from accepting it for divine know ledge, whic,h thUS, as so often, assumes the position as it were of a pure sample in a Ihoughtexperiment. {As when Professor Aycr in his you th, in spite of LWI-1-:1"'1-[<,1'1'11111 (/lid Logic, wal' observed roc.k ing on the noo r in a discussion and excla.iming .. God doesn 't know any negat ive facts! '') In this case we come up with the result : If il is kllown '''(11 p is unalterably true (because a present fact) still it doe s not follow that 1I<'Cf's.mrily p il> true even though the truth of p follows with logical necessity from it is known Ilwt p. This a ppears to St. Thomas far too paradoxical for hUman knowledge; he therefore infers that humans cannot k"ow future contingents and makes a suspiciously facile use of Boelhius's definition of eternity as illlermintl bilis vi'ae (Ow simlll et perleclll pol'seSy jo (the complete pOl>scssion all at once of endless life) ill order 10 compare God's knowledge of futurp contingents to our knowledge a t p resent facls, Our own knowledge of future even ts is only in their present causes; when l'bese do not absolutely necessitate their effect s. so that the elfects are contin~ent . he thinks. we cannot know them. But, we might argue on his own principles, whal causes in the world can not conceivably be tampered with . at least by divme power '! Thus we can k/lOW nothing of the f uture.

SI. Thol1/tI$ A quilltl$ SlImmn TlleoIOKhJf. Vol. I. Edited by Thomas Gilby. 165pp. 30s. Vol. 2, Edited by Timoth Y McDermott. 239pp. 35s, Yo-I. 3. Edited by Herbert McCabe. 117pp, 30s, Vol. 4, Edited by Thomas Gornalt, 138pp. 30s. Vol, 13. Edited by Edmund Hi ll. 227pp, JSs. Vol. 22, Edited by Anthon)' Ken·ny, 140pp. 30s. Eyre and SpoHiswoooc,

SI. Thomas surely did not need (0 their objects, But up 10 a short whi le adopt these devices: he had put his ago it was immensely common hand on the solu tion in tlhe distinc· in effect to dist inguish such objccts: tion between the true {Ie dicit} neces- did not Professor Ayer, itl common silY wllat is known fl· true and the with many ollhers, teach that all that f-alse de I'e pronouncement only was certain was eitller a truth of logic wlral is neas.mr)' is known. And or an expression of immw·ia te experith·is can be applied to human know- ence like .. I am imagining a red ledge no less than to divine, Kn ow- circle "-all else being at b~Stt merely ledge is not restricted to what could probabJe? These doctri.nes indeed not imaginably turn out mistaken: are now not so much taught; but it given t'hat there are not more sped/it.: is a standard method to test any grounds for refusing the t jtle" know- p.hi1o~phieal a ssertio n- c ,g .... Erno. · ledge" to my c1a.im that someth ing Lion a lways has an object " . .. A cause is true. it is sufficient that the claim . must be prior to its effe'ct ",- ·by contloes not lu rn oul mistaken. II may sidering. ·whe·the·r ..a counter-example be that J can conce-:ve circumstances to it can be conceived witihout conthat would prove me wrong; that Iradiclio.n, C!=, nua.d:ic.tion indeed may does not show that I may be wrong, have to be rather generously . conG. E. Moore was labouring to :this ceived: not eve ry irico ncei,,;ability conclus ion in his last years, but-be . can be displayed -a,s C? f the "fo rm

Old Woman

OVERWHELMED witb kimlnt'sses-nnd you ita'l! nothing. Thf"y bring you roses to refresh their hearls

nlld still the Litter voices. 'l'IH~y greet you sweetly. you arc now their child. they fl .ttter yOIi complctely, .md you have nothing to VrcsC'llt to them ohj ects to objects. just your used self.

Ouly a god I think could take such gifts and not fecl lmlred, Only a god could bear such manifold pC'nanccs. and be the vase for all these guilt y rOS(~8.

Yml arc no god and therefore should you snap suddenly out at them bC't\\'cI'n old t~cth like a fox: dying in a sweet countr y I should not turn from that poor twiAled face h:ty4~d in h i!. au tU11I11 by snlir.itllns ~lUiles.

felt-·· could n.ot get it out sa tisfalo.":tori ly.

.. But", someone says, " if the cnn'ce can turn out to be hot a fter all , then you may be wrong in say ing it won't n , Well. if it turns uu t hot I shal·J gran t I d :d not knuw it would nu t : but I say it will not. And why should its being possiblc to imagine my being wrong, prove mc not 10 know, in the casc where I tllrn o ut tu ha ve been right 1 .. But tha t makes an y proof that you kilo II' cap.\ble. of refutation. if o n examination the cofl"ee lurns out hot." So it is : I ca nnot have a beller proof that I know the cofl'ce wi ll no t be h()(, than I could have tha t the colfee will not he hot: and no proof of that would wilhstand its actuall y turning out to be hoI. . " But the reasons ror present knllwledge mllst be p resenl reasons, and if these do nut prove' the futu re contingen t a s.'iertion. the alll.'ged knowledge is not knowledge!" This is a gain the requi rement thai Ihe object of knowledge be necessary. None o f this ~hows me no t tll know now. Tu adapt 10 our own pu rpose.'\ t·he la st sentence of Aquinas's art icle : " Since thc ex.pre.~sion 'kno wn ' refers to the actual cun tc,.;t of knowing, the thing that is known , even though it is kn~l\vn 11011', can be charaC1Cr il.ed in itself in a way in which it cannot be cha racterized qUel be,longing 10 the actua l conlext of knowing (namel y. as future): in the same way, materiality i~ at·t.r ibuted to a stone as ~~~~~~/.t,~e l f, but not as an object of

it beimlged to the temper of St.

l AIN ClUCIITO;V S l'tIlTll

.. both thus and not thus", where the two occlirrenCes of the word" thus" a rc replaced by the same lerm, Sometimes an inconceiva bili ty seems irreducibly o-f Ihe kind wh~re the two ., thuses" receive dilferent subst itutions as in .. bOl·h coloured and not extended" or·-· .l0 take examples claimed by Aquinas ·· .. both a hUman being and lack ing any pOlenIi'llity for laugh ter ", .. bOlh an existell t by shari ng in ex istence and uncaused" (l a, 3. 6, and 44.1).

Thus what mighl at li rst seem archaic turns out on renection to confol'Ol to very general philosophica l pract ice: phi losophic understand· ing. we tend to think. concerns what must be so, Or if ph ilo..sophic unde rs.tanding is achieved by a successfu l ddineation of concepts. of ho w they happen to be in Ihis our - or any human- cult u re, then our great interesl is 10 n l.il~ what could not be supposed changed about a concept without quite changing what we arc talkin g abou t in using it , as we change Ihe propositions of geQmetry by chang.jng from one geometrical system to anolher·· ·what, that is, belongs to what SI. Thomas calls the I'lifio lormali.l· obh'cfi. Such a phra se, it wi ll be clear, is difficult to explain or to tran.'ilate ver y diree"t ly, unless one is to empl oy the gobbledegook of mere transverbali-7.ation- the original technique of the Latin translations of Aristo tle and lhe first English tra nslation of St. Thomas. The prescnt translat iun is very dillerent; one translator otfers

Robert Shaw

likely to say " '!Ihe lot " , We start meclU,\' in reblls " our philosophic ' activity' is' one of describing and clarifying · this milieu to ourselves. What we believe to exist we c redit and what we do not believe to exist we d iscredit, -not on grounds of any a I}riari conception of knowledge, language, mean ing llOd truth, On what grounds, Ihen '! Why do we nol. if we do nol, b~liev~ in the Evil Eye ?-in Which 51. Thomas. li,ke many present-day Neapoli tans. did believe, giving a rMionalist,ic account of the ·phenomenon (la I J 7. 3. ad2), It is to be feared that the rcason is oflell largely: bcc.au~'C the~ people a round us do not. But perhaps. we are not all entirely lazy: there is a great deal of work to do before we can face such questions, We wanlt to get clcar abnut the concepts we ha·bi tuall y use before we lrust ourselves as philosophers to use them for purposes beyond our immediate ken. So we accept common views. or rem·ain ill views not arrived at by philosophy while we work at concepts; and it is noteworthy that concepts of expe rie ncing are on ly some--equa l citizens, no moreamon.g those tha i we wanl to understand, The logica l fea tures of concepts, which we want to describe. are such as to nHlkc us need tools of phi losophic de.'~cription not always unl ike those u.'ied by a medieval philosopher. We I.'an ofot!!n see what he was at where nul' grcat grandfathers -sometimeo; even our falhcrs ---<:ouJd see nothing but useless subtleties tlnd dist inctions, The sor(ing OlJjt by Aquina" of th e de J't! and tie di(' TO necess :'lies confounded in •. what is known is necessaril y true " is something a presen t day English philosopher Cilll appreciate.

The retreat frllm atomism is, l.houg-h it is easy nut to re.alize !-his, f'llr more d:tlicu ll to carry out successruJ.1y than might appt!ar. Indeed it is well estahlished now that we cannot regard th e emotions as merely co nungenlly co nnected with the kind of objt::c(s Ihey ha ve and the aims they tend to make us ha ve, And it seems equall y clear that thoughts are characterized by what they are of, wit:h no s ub stan live being of their own: but how this is so is so inteme·ly obSl:ure that une su rveys the obscurities of th e scholastic eut: ill Ie/Iixiln'l<' , wihose actual it y is the same thing as the aClual uccu rrence of a thOUght of suc h~nd-such . with a not toraW y unfavourable eye, The medieval concept of in.tcntional existence . called I, jn~enti(}lla..l inexistence" by the scholastica ll y Irained philol>opher Brentano , may even be making a come-back. a reappearance in modern dress. But these matters are still very dark.

THE FLAG Thomas's lime and to hi s own not to p~ofcsl; originali ty but rather to ~gree "'lib previous aut ho rit ies as much a!' poss ible, And there wa s a long tradition, limi ting human knowledge to the necessary. Accord ingly we fiod 51. Thoma". maintaining lhis opinion. Of II self lihlS would not exclude history f rom being known, since Aristot le ~eld th at the past is neceiisary: but SI. Thomas goes fa rther than Ihis in his adherence to the Greek conception of knowledge; in the field of specu lalive rea .wn. he says everything derives from soene first . indemon· strable principles which are known of themselves. Indeed in at least One place ( I. II. XCIV 2c,) we find him ~aying tlhat everything in th is sphere IS .. founded upon " the principle of contradiction.

The most ambitious and successful novel to date by lhe author or TIl£' Hiding P/ac(' und TIt(· Stili Docta/,_ 21s. IUN

These V!CWl> put fo rward in th is manner certainly a·ppear archaic: but. un further reflection. are Ihey 50 after all ? Indeed if one speaks in Ihe manner of Plato of" objects of knowledge" and .. objects of opinion" it will b~ replied by everyone that th::-se th ings do nOI h~ve to dilr ... r in

William Walsh A HUMAN IDIOM A highly impoJ'ta nt new book by the author of T/I(' l../,\'l' 0/ I ,,;aginatioll.

25s. net

Andrew Wright HENRY FIELDING A brilliant study of Fielding's comic art by the author of Jalle Austell's NO\·els. 25s. l/el

Dickens : FROM PICKWICK TO DOMBEY A study of the first seven novels by STEVEN MAR CUS

Vernon Bartlett A BOOK A~OUT ELBA A lively guide to this popular island and its history,

/IIw'II'Q/t'd 2Is.II¥1

Chat to & • Windus