Nature and Scope of Synthesis in Functional Analysis and ......2017/05/16 · nature and scope of...

Transcript of Nature and Scope of Synthesis in Functional Analysis and ......2017/05/16 · nature and scope of...

NATURE AND SCOPE OF SYNTHESIS IN FUNCTIONAL ANALYSISAND TREATMENT OF PROBLEM BEHAVIOR

JESSICA D. SLATON

WESTERN NEW ENGLAND UNIVERSITY, NASHOBA LEARNING GROUP

GREGORY P. HANLEY

WESTERN NEW ENGLAND UNIVERSITY

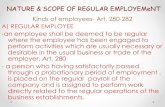

Functional analysis (FA) of problem behavior typically includes the contingent delivery of a sin-gle reinforcer following problem behavior. However, the FA literature also includes examples ofanalyses that have delivered multiple reinforcers, arranged multiple establishing operations inone or more test conditions, or both. These analyses have been successfully applied under het-erogeneous conditions over several decades and with various synthesized establishing operationsand reinforcers, but their qualitative details, outcomes, and contributions to the literature havenever been described in a comprehensive manner. The purpose of the current review is to:(a) identify articles that have reported the use of synthesized FAs or treatments; (b) describe thenature and scope of synthesis as it has been applied in the FA literature; (c) analyze outcomes ofsynthesized FAs and treatments to determine general benefits and disadvantages of synthesis;and (d) offer recommendations for future areas of research.Key words: functional analysis, problem behavior, synthesized FA, synthesized EOs,

treatment

The development of a functional analysis(FA) of problem behavior was a watershedmoment in behavior analysis. The methods andresults reported by Iwata, Dorsey, Slifer, Bau-man, and Richman (1982/1994) provided aseed from which a robust FA literature withmany branching lines of research has grownand from which current best practices in theassessment and treatment of problem behaviorhave been selected. In the thirty-five years sincethat publication, treatment of problem behaviorhas shifted from the use of arbitrary reinforcersand punishers (e.g., Corte, Wolf, & Locke,1971; Dorsey, Iwata, Ong, & McSween, 1980;Repp & Deitz, 1974) to the use of function-

based interventions, primarily those that replaceproblem behavior by identifying its reinforcersand using those same reinforcers to establish afunctionally equivalent alternative response(e.g., Carr & Durand, 1985; Hagopian, Fisher,Sullivan, Acquisto, & LeBlanc, 1998; Tiger,Hanley, & Bruzek, 2008). Identifying the rein-forcers for problem behavior also allows forextinction to be programmed (Iwata, Pace,Cowdery, & Miltenberger, 1994). Functionalanalysis is now considered a critical step inassessing and treating problem behavior(Beavers, Iwata, & Lerman, 2013; Hanley,Iwata, & McCord, 2003); treatments based onFAs are more likely to be efficacious and lesslikely to rely on punishment than treatmentsthat are not function-based (Campbell, 2003;Kahng, Iwata, & Lewin, 2002; Pelios, Morren,Tesch, & Axelrod, 1999).There are two components common among

FAs of problem behavior: a test condition inwhich at least one putative reinforcer is with-held and then delivered contingent on problem

This manuscript was prepared in partial fulfillment of aPh.D. in Behavior Analysis from Western New EnglandUniversity by the first author. We thank Rachel Thomp-son, Jason Bourret, and Jessica Sassi for their feedback onearlier versions of this manuscript and Christina Carusofor her assistance in collecting IOA.Address correspondence to: Gregory P. Hanley, West-

ern New England University, 1215 Wilbraham Road,Springfield, MA 01119. Email: [email protected]: 10.1002/jaba.498

JOURNAL OF APPLIED BEHAVIOR ANALYSIS 2018, 51, 943–973 NUMBER 4 (FALL)

© 2018 Society for the Experimental Analysis of Behavior

943

behavior, and a control condition in which thiscontingency is absent (Beavers et al., 2013;Hanley, 2012; Hanley et al., 2003; Iwata &Dozier, 2008). The logic of a test condition isthat by withholding a particular reinforcer(e.g., attention), the individual experiences anestablishing operation (e.g., deprivation ofattention) that evokes problem behavior main-tained by that reinforcer. The response thatcontacts that reinforcer during the test condi-tion presumably continues to occur because itis both evoked by the deprivation of that rein-forcer and subsequently strengthened by itscontingent delivery. The fundamental compo-nents of a test condition in an FA thereforeinclude an establishing operation (EO), theoccurrence of some response, and the deliveryof reinforcement contingent on that response.Reviews of FA literature (e.g., Beavers et al.,

2013; Hanley et al., 2003) and details from rel-atively large-n studies (e.g., Iwata, Pace, Dorseyet al., 1994) indicate that the majority of FAsprovide one reinforcer following problembehavior in any given test condition. For exam-ple, Iwata, Pace, Dorsey et al. (1994) reportedFAs of self-injurious behavior (SIB) for 152 par-ticipants who experienced multiple test condi-tions with a single reinforcer provided for SIBin each test condition (or with no programmedconsequences in the alone condition). Hanleyet al. (2003) and Beavers et al. (2013) bothnoted that approximately 90% of analysesincluded this same feature of providing a singlereinforcer following problem behavior, regard-less of other modifications to design or mea-sures (e.g., Bloom, Iwata, Fritz, Roscoe, &Carreau, 2011; Conners et al., 2000; Derbyet al., 1992; Iwata, Duncan, Zarcone, Ler-man, & Shore, 1994; Northup et al., 1991;Schlichenmeyer, Roscoe, Rooker, Wheeler, &Dube, 2013; Sigafoos & Saggers, 1995;Smith & Churchill, 2002; Thomason-Sassi,Iwata, Neidert, & Roscoe, 2011; Wallace &Iwata, 1999).

Though fewer in number, Beaverset al. (2013) also reported some examples ofpublished FAs in which multiple putative rein-forcers were evaluated in the same test condi-tion (e.g., Mueller, Sterling-Turner, & Moore2005; Sarno et al., 2011). However, Beaverset al. did not provide a comprehensive analysisof this subset of articles beyond noting thatarranging multiple consequences in a test con-dition can be methodologically complicated.That is, the simultaneous provision of multiplereinforcers could obscure a particular functionalrelation, thereby obfuscating data interpreta-tion. For example, when providing escape andtangible items contingent on problem behaviorin an FA test condition, it is unclear whetherproblem behavior is maintained by each ofthese reinforcers separately (i.e., multiple con-trol), by only one of the reinforcers(e.g., escape but not tangibles), or by the inter-action between the reinforcers (i.e., escape totangibles, and not escape or tangibles in isola-tion). Despite these potential challenges tointerpretation posed by FAs that involve thesimultaneous delivery of multiple reinforcers, anumber of examples in which multiple rein-forcers have been purposely arranged in a testcondition have been reported since the reviewby Beavers et al. (i.e., Call & Lomas Mevers,2014; Fisher, Greer, Romani, Zangrillo, &Owen, 2016; Ghaemmaghami, Hanley, & Jes-sel, 2016; Ghaemmaghami, Hanley, Jin, &Vanselow, 2015; Hanley, Jin, Vanselow, &Hanratty, 2014; Jessel, Hanley, & Ghaemma-ghami, 2016; Jessel, Ingvarsson, Metras,Kirk, & Whipple, 2018; Lambert et al., 2017;Lloyd et al., 2015; Payne, Dozier, Neidert,Jowett, & Newquist, 2014; Santiago, Hanley,Moore, & Jin, 2016; Slaton, Hanley, & Raf-tery, 2017; Strohmeier, Murphy, & O’Connor,2016). Moreover, the literature on FAs thatinclude combined reinforcement contingencieshas presented corresponding data on treatmenteffectiveness, such that interventions based onthese types of FAs have also been reported

JESSICA D. SLATON and GREGORY P. HANLEY944

(e.g., Ghaemmaghami et al., 2016; Ghaemma-ghami et al., 2015; Hanley et al., 2014; Jesselet al., 2018; Mann & Mueller, 2009; Payneet al., 2014; Santiago et al., 2016; Sarno et al.,2011; Slaton et al., 2017; Strand & Eldevik,2017; Strohmeier et al., 2016).The combination of reinforcement contin-

gencies has been one of the most prominentdevelopments in the FA literature since thereview published by Beavers et al. (2013); how-ever, reinforcement contingencies are not theonly component of an FA test condition thatcan be combined. A number of investigations(e.g., Call, Wacker, Ringdahl, & Boelter, 2005;Dolezal & Kurtz, 2010; O’Reilly, Lacey, &Lancioni, 2000) have examined the effects ofcombining multiple EOs within the same con-dition (e.g., diverting attention while present-ing demands). Likewise, a number of studieshave arranged reinforcement that is deliveredcontingent upon multiple topographies ofproblem behavior (e.g., aggression and SIB; seeBeavers et al., 2013).Throughout the remainder of this paper, we

use the word synthesized to refer to arrange-ments that involve multiple EOs, multiplepotential reinforcers, multiple response topogra-phies, or some combination. In particular, weuse synthesized EOs to describe the simulta-neous presentation of multiple EOs, synthesizedtopographies to describe multiple responsetopographies scheduled for reinforcement, andsynthesized reinforcers to describe the simulta-neous provision of multiple reinforcers. Wedescribe FAs that explicitly include synthesizedEOs, synthesized reinforcers, or both as synthe-sized FAs; we describe their corresponding

treatments as synthesized treatments. By contrast,we use isolated FA to describe an FA in which asingle reinforcer is provided in each test condi-tion and isolated treatment to describe its corre-sponding treatment. Finally, throughout thispaper, we use the term analyst to refer to theperson implementing the FA conditions ortreatment.In addition to the individual combination of

the above FA components, it is possible that allaspects of an FA contingency might be synthe-sized. That is, one could synthesize EOs,topographies, and reinforcers to arrange a syn-thesized contingency. Such an arrangementwould be in contrast to the FA proceduredescribed by Iwata et al. (1982/1994) in whichnone of these components is purposely synthe-sized. We may thus describe all FAs as existingsomewhere on a continuum between isolatedand synthesized. Figure 1 depicts points alongthis continuum. Toward the isolated end of thecontinuum would be FAs in which all compo-nents of the contingency are isolated: A singleEO is presented and a single topography pro-duces a single reinforcer. For example, demandsare presented and spitting produces escape fromthose demands. Toward the synthesized end ofthe continuum would be FAs in which all com-ponents of the contingency are synthesized:Multiple EOs are simultaneously presented,multiple response topographies are scheduledfor reinforcement, and multiple reinforcers aresimultaneously provided following problembehavior. For example, demands are presentedand tangibles are removed; spitting, hitting, orkicking each produces escape from thedemands plus access to the tangible items. In

1 EO

Synthesized

1 topography1 reinforcer

1 EOSynth. topog.1 reinforcer

Synth. EOs1 topography1 reinforcer

Synth. EOs

1 reinforcer

Synth. EOsSynth. topog.

Synth. reinforcersSynth. topog.

Isolated

Synth. EOs1 topography

Synth. reinforcers

Figure 1. Points along the continuum of FAs from isolated to synthesized. EO = establishing operation; synth. =synthesized; topog. = topographies.

945SYNTHESIS REVIEW

between these points are FAs in which differentcomponents are synthesized or isolated to vary-ing degrees.There are a number of unanswered questions

regarding the prevalence of use as well as thefeatures and outcomes of synthesized FAs andsynthesized treatments. For example, we do notknow the extent to which synthesized FAs andtreatments have been reported in the literature,nor do we have information regarding theirgeneral features (e.g., settings in which theyhave been conducted; specific combinations ofEOs or reinforcers that have been evaluated).We also do not know the extent to which syn-thesized FAs produce differentiated outcomes,the overall effectiveness of treatments based onsynthesized FAs, or the contexts in which theseoutcomes have been obtained. Describingexamples of synthesis already present in the lit-erature and analyzing their outcomes is animportant step in evaluating the benefits andlimitations of synthesizing FAs and FA-basedtreatments. Tacting the use of synthesis in FAsand treatments where applicable is importantbecause it provides a conceptual frameworkwithin which to interpret the collective resultsof studies that may otherwise seem unrelated.In other words, the group of articles that couldpotentially inform our understanding of the rel-ative merits or limitations of synthesized FAcomponents and synthesized treatments has notyet been identified.There are also important questions to be

answered regarding how synthesized FAs andtreatments compare to their isolated counter-parts. Such comparisons could be made withinthe same participant and could examine the rel-ative benefits of synthesized and isolated FAsrelative to treatment development, treatmentoutcomes, programming for generalization, andclinical utility. A comprehensive comparison ofthe extent to which synthesized and isolatedFAs produce differentiated outcomes is beyondthe scope of the current paper, but there isinformation to be gleaned from the small

number of cases in which the two types of FAshave been compared. To date, there have beena few studies that have directly compared syn-thesized and isolated contingencies (e.g., Fisheret al., 2016; Ghaemmaghami et al., 2015; Sla-ton et al., 2017), and their relative contribu-tions will be discussed herein. Likewise, a rangeof methods have been reported for determiningthat a synthesized contingency was necessary toproduce a differentiated FA or effective treat-ment in a particular instance (i.e., such resultswere obtained only when a synthesized contin-gency was applied), but these methods havealso not been discussed together in terms oftheir relative value. An integrated discussionmight provide some initial guidance for design-ing FAs and treatments with isolated or synthe-sized variables.Given potential problems with data interpre-

tation posed by the use of synthesized rein-forcers and the number of unansweredquestions regarding the relative contributions ofsynthesized FAs and treatments, a review of theprevalence of use, methods, and outcomes ofsynthesized FAs and their corresponding treat-ments seems timely and warranted. The pur-pose of this review is to attempt to answer thequestions above by describing and analyzingexamples of synthesized FAs and treatments,identifying gaps in the literature, and providingrecommendations for future lines of research.

METHODS

Article Identification and SelectionWe documented the search process using

guidelines described in the Preferred ReportingItems for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Liberati et al.,2009). Figure 2 provides a flow chart illustrat-ing this process, including the number of arti-cles identified by each search, the number ofarticles excluded at various points in the process(and their reason for exclusion), and the finalnumber of articles included. First, we searched

JESSICA D. SLATON and GREGORY P. HANLEY946

PsycInfo for the keyword functional analysis incombination with each of the following: synthe-sized, multiple control, multiple reinforcers, com-bined reinforcers, combined + problem behavior,multiple + problem behavior. All articles

returned by these searches were screened bytitle and abstract to determine whether thestudy included an FA of problem behavior.Articles that appeared to meet inclusion criteriawere then screened by reviewing the methods

noit

acifit

ne

dIg

nin

eer

cS

ytilibi

gilE

de

dul

cnI

Literature search: PsycInfo

Functional analysis + synthesized (14)

Functional analysis + multiple control (20)

Functional analysis + multiple reinforcers (6)

Functional analysis + combined reinforcers (2)

Functional analysis + combined + problem behavior (29)

Functional analysis + multiple + problem behavior (103)

Limits: Peer reviewed, human population, English only

Search results combined:

n = 174

Results screened

by abstract and titleExcluded (n = 78)

Duplicate (20)

Review or discussion paper (15)

Not an FA of problem behavior (17)

Not behavior analytic content (26)Included by title and

abstract (n = 96)

Full text screened for

eligibility

Excluded (n = 72)

AB model (1)

Aggregate data (1)

Did not include synthesized EOs or

reinforcers (66)

Not an FA of problem behavior (4)Included (n = 24; 119)

Other sources (n = 31; 168)

Reference list of screened articles (25; 99)

Google scholar alerts (6; 69)

Total included (n = 55; 287)

Figure 2. PRISMA flow chart describing article identification and inclusion process. Numbers in regular font indi-cate the number of articles in that category; numbers in italics indicate the total number of applications in that category.

947SYNTHESIS REVIEW

section and figures in the article to determinefinal eligibility (i.e., determine whether synthe-sized EOs, synthesized reinforcers, or both werearranged in at least one test condition for atleast one participant). Second, we created aGoogle Scholar alert for any articles with thefollowing key words and screened these alertsas they were received: functional analysis, func-tional analysis + autism, functional analysis +aggression, functional analysis + SIB. Third, weidentified additional articles from the referencelists of the articles detected through PsycInfoand Google Scholar.We included articles that reported FAs of

problem behavior in which consequences wereprovided following problem behavior (i.e., theA-B-C model) and which also met at least oneof the following criteria: (a) the FA includedsynthesized EOs in at least one test condition;or (b) the FA included synthesized EOs andsynthesized reinforcers in at least one test con-dition; or (c) the treatment included synthe-sized EOs, synthesized reinforcers, or bothregardless of whether the FA had included thesevariables. We excluded studies in which FA dif-ferentiation and treatment effects could not bedetermined for each individual participant(e.g., large n studies reporting aggregated dataor samples of participant data).Interobserver agreement (IOA) for inclusion

of articles was obtained by having a second per-son independently screen 20% of all articlesreturned by each search. IOA across all searchterms averaged 88% (range, 83% - 100%).

Variables CodedWe used details from the Method section of

each article to code the following variables foreach application of a synthesized FA or treat-ment: setting; which components of the FA ortreatment were synthesized (EOs only orEOs + reinforcers); which EOs or reinforcerswere synthesized (e.g., attention + tangibles);how those EOs or reinforcers were selected for

synthesis; which topographies of problembehavior were reinforced; how those topogra-phies were selected. We used visual inspectionof figures to code whether the FA was differen-tiated (our interpretation was always consistentwith the authors’ interpretation), whether anundifferentiated FA or ineffective treatmentoccurred first,1 whether treatment data wereincluded, and whether the experimentersdirectly compared synthesized and isolated con-ditions. We defined an application as each dis-tinct setting, analyst, set of stimuli, orcontingency evaluated during FA or treatment.For example, a synthesized FA in which a clini-cian and a parent both served as analysts andwhich was then followed by a synthesized treat-ment would be scored as three applications(2 FAs and 1 treatment; e.g., participant Gailin Hanley et al., 2014). We did not score repli-cations of the same application. For example, ifa synthesized treatment was compared to anisolated treatment in a reversal design, we didnot score each reversal as a new application.IOA was obtained by having a second personindependently score 20% of articles. An agree-ment was scored if both observers coded thesame response for a particular variable in thesame article (e.g., both observers coded “home”as the setting for the FA, or both observerscoded “attention, tangibles” as the reinforcersthat were synthesized). IOA was calculated bydividing the total number of agreements by thetotal number of agreements plus disagreements(i.e., the total number of articles for whichIOA was scored) and multiplying by 100. IOAacross all variables averaged 97% (range, 80 –100%). Specific IOA for each variable is as fol-lows: setting, 100%; which components of theFA or treatment were synthesized (EOs only orEOs + reinforcers), 100%; which EOs or

1In cases in which no visual display of previous FA iter-ations was included, we relied on the Method section inwhich authors stated that a previous FA had occurred andwas undifferentiated. This occurred in two FA applica-tions (1.5% of all synthesized FAs).

JESSICA D. SLATON and GREGORY P. HANLEY948

reinforcers were synthesized (e.g., attention +tangibles), 89%; how those EOs or reinforcerswere selected for synthesis, 100%; whichtopographies of problem behavior were rein-forced, 100%; how those topographies wereselected, 100%; number of differentiated FAapplications, 100%; whether an undifferen-tiated FA or ineffective treatment occurred first,100%; number of treatment applications,100%; number of FA applications, 80%;whether isolated and synthesized conditionswere directly compared, 100%.

Evaluating Treatment EffectsWe used the program WebPlot Digitizer

(https://automeris.io/WebPlotDigitizer/) toextract the value of individual baseline andtreatment data points depicted on treatmentgraphs. WebPlot Digitizer is a free programthat allows users to load an image of a graphand click on individual data points to calculatetheir X and Y values. We then calculated meanbaseline reduction (MBLR) and percentage ofnonoverlapping data (PND) for each treatmentapplication using the same methods reportedby Campbell (2003): MBLR was calculated bysubtracting the mean of all data points in thefinal treatment phase from the mean of all base-line points in the first baseline phase, dividingby the mean baseline, and multiplying by 100;PND was calculated by counting the numberof data points in the final treatment phase thatfell below the lowest data point in the firstbaseline phase, dividing by the total number ofdata points in the final treatment phase, andmultiplying by 100. For cases in which datawere reported for both a synthesized and anisolated treatment, MBLR and PND were alsocalculated for the isolated treatment. Afterobtaining MBLR and PND across all synthe-sized and isolated treatment applications, weconducted an independent samples t-test todetermine whether the difference between thetwo was statistically significant.

RESULTS

As depicted in Figure 2, we identified 55 arti-cles for inclusion. This sample yielded287 applications of synthesized FAs or treat-ments across 149 participants, publishedbetween 1995 and January 2018. Figure 3shows cumulative number of FA and treatmentapplications across publication year. The major-ity of applications (66.9%) were publishedsince 2014, indicating that the use of synthe-sized EOs or synthesized reinforcers hasbecome increasingly more common in the lastseveral years. About half of the 287 applicationswere FAs (n = 148; 51.6%); the remaining139 applications (48.4%) were synthesizedtreatment applications. We found applicationsat three points along the synthesis continuum(see Figure 1): FAs and treatments in whichEOs were synthesized but reinforcers were not

0

25

50

75

100

125SCA

SEOA

1995 2000 2005 2010 2015

Cu

mu

lati

ve

FA

ap

plica

tio

ns

0

25

50

75

100

Year

Designed from SCA

Designed from SEOA

Designed from

isolated FA

Cu

mu

lati

ve

trea

tmen

t ap

plica

tio

ns

Figure 3. Cumulative applications of synthesized FAsand treatments between 1993 and January of 2018.

949SYNTHESIS REVIEW

(28 FAs and 8 treatments)2; FAs and treat-ments in which EOs, topographies, and rein-forcers were all synthesized (i.e., a synthesizedcontingency; 120 FAs and 131 treatments). Ofthose 131 treatments with synthesized contin-gencies, 99 were designed from an FA withsynthesized contingencies and 32 were designedfrom an isolated FA. We did not find anyexamples in which EOs and reinforcers weresynthesized but topographies were not. Table 1presents a summary of these different catego-ries. The sections below present descriptions ofthese types of applications, followed by analysisof their methods, features, and outcomes.

Types of Synthesized FAs and TreatmentsSynthesized EOs. We offer the term synthe-

sized EO analysis (SEOA) to describe applica-tions in which two or more EOs aresimultaneously presented, but only one rein-forcer was delivered following problem behavior(in an FA) or an alternative response(in treatment). For example, demands mighthave been presented while attention was alsodiverted from the individual, thus combiningEOs for escape and attention; problem behaviormay produce only the attention of the adult,while the demand continues to be presented

(e.g., Call et al., 2005). Table 2 lists each SEOAwe reviewed and the combinations of EOs eval-uated. Most of the 36 SEOA applications wereviewed were FAs (77.8%); the remaining weretreatment applications following those FAs.We noted two distinct types of synthesized

EOs: those that evaluated external variables(i.e., socially-mediated events that occur outsidethe individual’s body, such as the delivery ofattention or escape; e.g., Dolezal & Kurtz, 2010)and those that evaluated internal variables(i.e., physiological events that occur inside theindividual’s body, such as sleep deprivation or ill-ness; e.g., Kennedy & Meyer, 1996). SEOAshave evaluated the interaction between externalvariables (e.g., attention + escape EO) or betweenexternal and internal variables (e.g., escape EO +sleep deprivation). Carr and Smith (1995) notedthat internal EOs can interact with external EOsto produce problem behavior. For example,SEOAs have demonstrated that the evocativeeffects of demands can depend on the presence ofsleep deprivation (O’Reilly, 1995), allergy symp-toms (Kennedy & Meyer, 1996), or ear infec-tions (O’Reilly, 1997), such that the presentationof demands evokes problem behavior only whenthese internal EOs are also present.In two applications, an SEOA demonstrated

that SIB maintained by automatic reinforce-ment occurred at high rates across all condi-tions only when the child also had a sinusinfection and not when the child was healthy

Table 1Types of Synthesized FAs and Treatments

Type of Synthesized Application Number of Applications Earliest Example Most Recent Example

FA (n = 148)SEOA 28 O’Reilly (1995) Call (2014)SCA 120 Bowman (1997) Jessel (2018)Treatment (n = 139)Designed from SEOAs 8 Horner (1997) Call (2014)Designed from SCAs 99 Bowman (1997) Jessel (2018)Designed from isolated FAs 32 Lalli (1996) Zangrillo (2016)

Note. Examples of earliest and most recent articles are listed by first author and publication year.SEOA = synthesized establishing operation analysis; SCA = synthesized contingency analysis.

225 of these 28 applications also included synthesizedtopographies (i.e., points three and four along thecontinuum).

JESSICA D. SLATON and GREGORY P. HANLEY950

(Carter, 2005). Psychotropic medications areanother variable that can interact with externalEOs to produce changes in function of problembehavior (see Cox and Virués-Ortega, 2016, fora recent review). The correlation between inter-nal events and problem behavior can be demon-strated by initiating sessions on days when theseEOs are present and on days when these EOsare absent, allowing for a direct comparisonbetween isolated EOs (e.g., escape only) andsynthesized EOs (e.g., escape + sleep depriva-tion). The impact of these internal events is cor-relational because the events cannot be directlymanipulated by the analyst during the FA; thisposes some challenges in that the analyst mustwait for these events to occur and then imple-ment the SEOA conditions.In contrast to difficulties with manipulating

internal EOs, a number of studies have directlymanipulated external EOs. As an example, Callet al. (2005) evaluated a condition in whichdemands were presented while access to tangibleitems was restricted (participant Kevin; escape +tangible EO) and a condition in which demandswere presented while attention was diverted(participant Richard; escape + attention EO).Contingent on problem behavior, only one of

these reinforcers was provided (escape but nottangibles for Kevin; attention but not escape forRichard). Problem behavior for both partici-pants was elevated during their synthesized EOcondition relative to isolated EO conditions,indicating that their problem behavior dependedon the interaction between two EOs and wasnot sensitive to either EO in isolation. Theseprocedures were replicated by Dolezal and Kurtz(2010), who compared a synthesized EO condi-tion to isolated EO conditions and demon-strated that problem behavior for a child withtraumatic brain injury depended on the interac-tion between EOs for escape and attention.Synthesized contingencies. We offer the term

synthesized contingency analysis (SCA) todescribe applications in which multiple EOsare simultaneously presented and all corre-sponding reinforcers are delivered followingproblem behavior (in an FA) or for some alter-native response (in treatment). For example,tangible items may be removed and demandsmay be presented (combining EOs for escapeand tangible items; e.g., Slaton et al., 2017;Strohmeier et al., 2016); problem behavior maythen produce escape from the demand andsimultaneous access to the tangible items.

Table 2Details and References for Synthesized Establishing Operation Analyses

Synthesized EOs First Author (Year) Participants

Noise + ear infection O’Reilly (1997) MarySinus infection + all isolated FA conditions Carter (2005)

Lohrmann (2001)GaganJamie

Escape + allergy symptoms Kennedy (1996) RudolfoEscape + sleep deprivation O’Reilly (1995)

Kennedy (1996)ShawnMarcello, Mimi

Tangibles + sleep deprivation Horner (1997) KarlEscape + tangibles Call (2005)

Call (2014)KevinJett

Attention + escape Call (2005)Dolezal (2010)

RichardKyle

Attention + tangible Lalli (1998) Dave, Carter, DanAttention + client location Adelinis (1997) AndyEscape + schedule change Horner (1997) Clay, PatEscape + noise O’Reilly (2000) EilisAttention + noise Bowman (2013) Phillip

Note. EO = establishing operation.

951SYNTHESIS REVIEW

Table 3 lists each SCA we reviewed, includingthe synthesized contingency evaluated in eachapplication. Of the 219 SCA applications wereviewed, 120 were FAs (54.8%) and 99 weretreatments. We found two qualitatively differenttypes of synthesized contingencies: those thatcombined the typical reinforcers evaluated inisolated FAs (e.g., escape + attention; Iwataet al. 1982/1994), and those that combined idi-osyncratic reinforcers that do not easily fit intoany of the typical isolated categories.As an example of the latter type of synthesized

contingency, several authors have reported exam-ples of problem behavior evoked by the denial ofthe participant’s mands (e.g., Bowman, Fisher,Thompson, and Piazza, 1997; Eluri, Andrade,Trevino, & Mahmoud, 2016; Roscoe, Schlichen-meyer, & Dube, 2015). Bowman et al. (1997)were the first to describe this contingency type.These experimenters began each test session byoccasioning and then denying the child’s mands.The authors describe this denial as “deviat[ing]from the activity specified by the child ... Forexample, if the child requested that the analystsing a specific song while walking in a circle, theanalyst might continue to walk in a circle but dis-continued the song or altered the words or mel-ody of the song” (p. 255). In other words, theanalyst denied the mand and engaged in a spe-cific incompatible activity related to the request.Contingent on problem behavior, the analyst ter-minated the incompatible activity and grantedthe child’s request. We consider this an exampleof a synthesized contingency because two EOswere present in the test condition: (a) the child’smands were denied, and (b) the analyst engagedin an incompatible activity related to the mand.Problem behavior produced both correspondingreinforcers: (a) the analyst terminated the incom-patible activity (i.e., provided negative reinforce-ment), and (b) the analyst provided access to theactivities requested by the child (i.e., providedpositive reinforcement). Several authors havereported similar arrangements in which a seem-ingly preferred ongoing activity was interrupted

with another activity, and problem behavior pro-duced termination of the new activity and accessto the previous activity (Adelinis & Hagopian,1999; Fisher, Adelinis, Thompson, Worsdell, &Zarcone, 1998; Hagopian, Bruzek, Bowman, &Jennett, 2007; Hanley et al., 2014). Hagopianet al. (2007) noted that problem behavior in thistype of “interruption analysis” could be a func-tion either of negative or positive reinforcement,in that some activity is terminated and someother activity is initiated. The synthesized rein-forcers in these FAs could be evaluated in isola-tion (e.g., a mand compliance test condition inwhich the adult terminates the nonrequestedactivity without initiating the requested activity);however, we found no instances in which experi-menters attempted to do so.In other cases, contingencies have been syn-

thesized even though their constituent partscould easily be evaluated separately. For exam-ple, Payne et al. (2014) reported SCAs inwhich escape and attention (participantAndrew) or attention and tangibles (participantSamantha) were evaluated as reinforcers forproblem behavior. These reinforcers were syn-thesized based on observations during a previ-ously ineffective treatment (i.e., problembehavior was not reduced to clinically accept-able levels during the treatment based on theinitial isolated FA). Mann and Mueller (2009)reported an SCA in which contingent access toattention and tangibles was presented based onparental report that the child often experiencedattention from parents and access to TV fol-lowing problem behavior. As a third example,Hanley et al. (2014) reported SCAs in whichmultiple reinforcers were combined for threechildren with autism spectrum disorder (atten-tion + tangibles for Gail; escape + tangibles forBob3; escape, attention, tangibles, and mandcompliance for Dale). These reinforcers could

3Based on the description of Bob’s test condition pro-vided in Hanley et al. (2014), we have categorized hiscontingency as escape to previous activity (see Table 3).

JESSICA D. SLATON and GREGORY P. HANLEY952

have been evaluated in isolation (and were forGail), but were combined based on parentreports of how they typically responded toproblem behavior. For instance, Dale’s parents

reported that when Dale aggressed towardsthem or it appeared that Dale was about tohave a “meltdown,” they relented with theirinstructions, redirected him to a preferred

Table 3Details and References for Synthesized Contingency Analyses

Synthesized Contingency First Author (Year) Participants

Escape to mand compliance Bowman (1997) Ben, JerryO’Connor (2003) PeteRoscoe, Schlichenmeyer (2015) Daniel, NateEluri (2016) PabloJessel (2016) Allen, Mike, Jesse, JianSchmidt (2017) Daryl, LarryTorres-Viso (2018) Amy

Escape to previous activity Adelinis (1999) RaffieFisher (1998) Ike, TinaHanley (2014) BobHagopian (2007) Perry, Maxwell, Kelly

Escape to rituals / stereotypy Leon (2013) LauraRispoli (2014) Timmy, John, DiegoJessel (2016) SamSlaton (2017) Chloe

Attention + tangibles Brown (2000) JimGhaemmaghami (2016) Jack, NicoHanley (2014) GailMann (2009) MadisonPayne (2014) SamanthaSantiago (2016) KarenStrand (2017) John

Escape + tangibles Fisher (2016) CameronJessel (2016) Kristy, Jim, Carson, Chris, MitchJessel (2018) Joe, Stan, Matt, Ken, Tim,

Zane, Mike, Dace, LarryLambert (2017) S-2Lloyd (2015) Abhi, SidRoscoe, Schlichenmeyer (2015) JimSlaton (2017) Riley, Dylan, Jeff,Strohmeier (2016) S-1

Escape + attention Mueller (2005) BobFilter (2009) DylanMay (2013) JaylinPayne (2014) AndrewSarno (2011) Brandon, Franklin, J’Marcus

Escape + attention + tangibles Fisher (2016) Alan, Allie, Sylvia, TinaGhaemmaghami (2015) DanJessel (2016) Jeff, Gary, Wayne, Earl,

Keo, Lee, PaulJessel (2018) Aaron, Kane, John, Alex, Sarah,

Annie, DanSantiago (2016) ZekeSlaton (2017) Diego, Emily, Kyle, Jonah

Escape + attention + tangibles + mand compliance Ghaemmaghami (2016) AlexHanley (2014) DaleJessel (2016) Jian

Escape + preferred conversation topics Jessel (2016) Sid, Beck, SteveSantiago (2016) KarenSlaton (2017) Mason

953SYNTHESIS REVIEW

activity in an attempt to calm him, and madetheir attention available to prevent any furtherescalation of problem behavior.Synthesized variables in treatment only. We

found 32 applications across 12 articles inwhich the pretreatment FA was conducted withisolated reinforcers, but the subsequent treat-ment included synthesized reinforcers. Table 4lists the treatment-only applications wereviewed, including which reinforcers wereidentified in the isolated FA and what type oftreatment was experienced. These examplesrepresented 23% of all treatment applications.In other words, approximately one-fourth of allsynthesized treatments were based on theresults of FAs that included isolated EOs orreinforcement contingencies.For example, Lalli and Casey (1996), Piazza

et al. (1997), and Piazza, Hanley, Fisher, Ruy-ter, and Gulotta (1998) reported cases in whichan isolated FA indicated control by multiplereinforcers (e.g., attention, escape), but separate

treatments based on each isolated reinforcerwere not effective in reducing problem behaviorto acceptable levels. These experimenters com-bined the reinforcers detected by the isolatedFA into an effective treatment consisting of asingle synthesized contingency. In each case,the synthesized treatment was directly com-pared to the isolated treatment in a multiele-ment or reversal design, and treatment effectswere observed only during the application oftreatments that involved synthesized rein-forcers. As another example, Bachmeyeret al. (2009) reported synthesized treatmentapplications in which multiple reinforcers aswell as multiple forms of extinction were evalu-ated. These experimenters conducted an iso-lated FA of inappropriate mealtime behaviorand found that problem behavior was sensitiveto escape and attention separately. Escapeextinction only, attention extinction only, andcombined escape/attention extinction condi-tions were then compared in a multielement

Table 4Details and References for Treatment-only Applications

First Author (Year) Isolated FA Outcomea Isolated Treatmentb Synthesized Treatmentc

Lalli (1996) Escape, attention Escape Escape to attentionPiazza (1996) Escape, attention, tangibles – Escape to tangibles and attentionPiazza (1997) Andy: esc, att

Carly: esc, att, tangBen: esc, att, tang

AttentionEscape

Andy: esc. to tang.Carly: esc. to tang.Ben: esc. to tang.

Piazza (1998) Escape, attention, tangibles AttentionEscape

Tom: esc. to tang, attJerry: esc. to att.

Harding (2002) Escape, tangibles EscapeTangibles

Escape to tangibles

Hoch (2002) Mickey: escapeEmily: escapeSean: escape, tang.

Mickey: N/AEmily: escapeSean: escape

Escape to tangibles

McComas (2002) Escape – Escape to tangiblesBachmeyer (2009) Attention, escape Attention

EscapeEscape extinction + attention extinction

Falcomata (2012) Escape, attention, tangible – Escape to tangibles and attentionFalcomata (2013) Escape, attention, tangibles – Escape to tangibles and attentionFalcomata (2014) Escape, attention, tangibles Attention Attention + tangiblesZangrillo (2016) Escape Escape Escape to tangibles

Note. Esc = escape; Att = attention; Tang = tangibles. In cases where participants are not listed separately, thismeans the information in that cell applies to all participants in the study.a Denotes the reinforcers identified separately during an isolated FA.b The contingency applied for appropriate behavior during treatment conditions with one reinforcer.c The contingency applied for appropriate behavior during treatment conditions with synthesized reinforcer.

JESSICA D. SLATON and GREGORY P. HANLEY954

and reversal design (participants Tyler, Savan-nah, Ella) or a multielement within a multiplebaseline design (participant Matthew). Duringthe escape extinction condition, attention wasprovided as a reinforcer for problem behaviorand escape was withheld; during the attentionextinction condition, escape was provided as areinforcer for problem behavior while attentionwas withheld; during the combined extinctioncondition, both reinforcers were provided forappropriate behavior. Problem behavior wasreduced to clinically acceptable levels for allparticipants only when both reinforcers andboth forms of extinction were synthesized.In a more recent example, Zangrillo, Fisher,

Greer, Owen, and DeSouza (2016) conductedan isolated FA and then compared isolated andsynthesized treatments (escape-only vs. escapeto tangibles). The pretreatment (isolated) FAfor both participants was differentiated forescape; problem behavior was not differentiatedfor tangibles for either participant in their iso-lated tangible conditions. However, the treat-ment comparison for both participantsindicated that providing escape to tangibles wasmore effective in eliminating problem behaviorduring FCT and subsequent reinforcementschedule thinning. Problem behavior persistedduring treatments that were based on theescape-only contingency and schedule thinningwas not successful in this context, suggestingthat tangible reinforcers were relevant to theproblem behavior, even though the isolated FAdid not identify contingent access to tangiblesas a reinforcer for problem behavior.

Analysis of Synthesized FA and TreatmentFeaturesSettings. Synthesized FAs (i.e., SEOAs and

SCAs) and their resultant treatments have beenconducted across a variety of settings, rangingfrom natural environments to highly specializedsettings. Over one third (35.9%) of all applica-tions were conducted in natural environments

where the individual typically spends his or hertime; these included at home, at school, or atadult day placements (e.g., vocational or dayhabilitation facilities). Outpatient clinicsaccounted for 39.7% of applications; theremaining 19.9% of applications were con-ducted on inpatient units.Topographies. Topographies of problem

behavior reinforced in synthesized FAs includedaggression, SIB, disruption (including motorand vocal disruptions, flopping, climbing onfurniture), spitting, elopement, crying, mouth-ing, and inappropriate sexual behavior. Mostsynthesized FAs evaluated multiple responsetopographies; 81% did so by reinforcing dis-similar responses (e.g., aggression and SIB), and17% did so by reinforcing similar responseswithin the same general category(e.g., aggression in the form of hitting andkicking). There were three applications (2%)that evaluated a single topography only (cryingin Bowman, Hardesty, & Mendres-Smith,2013; self-biting for participant Rudolfo inKennedy & Meyer, 1996; mouthing inLohrmann-O’Rourke & Yurman, 2001), andthree applications in which authors did notspecify whether multiple topographies werereinforced (Lambert et al., 2017; O’Reillyet al., 2000). In approximately half of applica-tions (49%), it appears that the topographiesreinforced in the FA were selected because theywere the specific behaviors for which the indi-vidual was referred (i.e., the authors providedno additional information regarding interviews,observation, or other methods that were usedto cull response topographies for analysis). TheMethod sections of most articles reported thatthe participant had a history of or was referredfor specific problem behaviors; we may inferthat these were the behaviors reinforced duringthe FA. Topography selection based on recordreview was not reported. Topographies wereselected through an open-ended interview inwhich teachers or caregivers answered questionsregarding the individual’s problem behavior in

955SYNTHESIS REVIEW

46.7% of articles; 7.2% of articles also reportedreinforcing precursor responses as well as prob-lem behavior.Conditions under which synthesis is applied.

We identified two distinct conditions underwhich researchers have conducted synthesizedFAs. In 17.1% of all applications, the use ofsynthesis was preceded by an isolated FA thatwas not differentiated (e.g., Bowman et al.,1997; Fisher et al., 1998). Synthesis wasapplied in these cases in an attempt to obtainmore conclusive results. For the remainder ofthe FA applications, the use of synthesis wasbased on an interview or observations that sug-gested certain variables were operating togetherto influence problem behavior. In other words,a large majority of experimenters who con-ducted synthesized FAs did so as the first itera-tion, rather than designing these test conditionsonly after other methods were unsuccessful.This finding may be somewhat counterintuitivebecause the majority of published FAs includeisolated rather than synthesized reinforcers(Beavers et al., 2013); one may thereforeassume that in most applications of synthesis,analysts attempted to use isolated reinforcersfirst, and only resorted to synthesis when thosemethods were inconclusive. Examining thesedata by publication year provides some addi-tional context. Most synthesized FAs have beenpublished since 2014; 12% of those FAs werepreceded by an initial isolated FA. Of the33.1% of synthesized FAs that were publishedbefore 2014, 22% were preceded by an initialisolated FA. In other words, experimenters werealmost twice as likely to conduct an isolated FAfirst before attempting a synthesized FA priorto 2014; the tendency for a synthesized FA tobe the first iteration of an FA (when they arereported) is fairly new and is possibly associatedwith the publication of Hanley et al. (2014), inwhich a comprehensive FA and treatment pro-cess relying on synthesis was initially reported.It is important to note, however, that themajority (73%) of synthesized FAs published

since 2014 have been conducted by current orformer researchers from the Hanley lab.Likelihood of differentiation. A high percent-

age of all synthesized FAs were differentiated(139 out of 148; 94%). There were six SCAapplications that were undifferentiated (partici-pant Sylvia in Fisher et al., 2016; participantsJim and Daniel in Roscoe, Schlichenmeyeret al., 2015; participant Gail [with analyst] inHanley et al., 2014; Participant 2 in Lambertet al., 2017). For Sylvia, Jim, and Daniel, anisolated FA was also undifferentiated; the iso-lated FA occurred after the SCA for Sylvia andbefore the SCA for Jim and Dave. For Gail, asecond SCA application with her mother wasdifferentiated. There were three SEOA applica-tions that were undifferentiated and interpretedas indicating an automatic function becauseresponding persisted across all conditions(Carter, 2005). Beavers et al. (2013) alsoreported that 94% of published FAs (includingthose reviewed by Hanley et al., 2003) weredifferentiated; thus, the likelihood of differenti-ation for synthesized FAs is comparable to thedata reported by those authors, though thenumber of applications is from a considerablysmaller sample size (148 in the present review,compared to 981 combined across Beaverset al. and Hanley et al.). It is also important tonote that most synthesized FAs detectedsocially mediated reinforcers; there were onlyfour applications (2.7%) in which an automaticfunction was implicated.Reinforcer combinations. Most SCAs (91.7%)

included escape to some other reinforcer(s):escape to different combinations of tangiblesand attention (25%); escape to some type oftangibles, including preferred activities (24%);escape to mand compliance, including access toattention or preferred activities (16.7%); escapeto a previous ongoing activity (7.3%); escape tosome form of attention, including preferredconversations (12.5%); escape to ritualistic orstereotypic behavior (6.3%). The remaining8.3% of SCA applications included a

JESSICA D. SLATON and GREGORY P. HANLEY956

combination of attention and tangibles. It ispossible that escape was reported so frequentlybecause the presentation of demands in thecontext of an ongoing preferred activity mayfurther establish the value of that activity. It isalso possible that parents and teachers are morelikely to report that problem behavior tends tooccur in the context of demands because lackof compliance with typical daily demands istheir most pressing concern.Demonstrating necessity of synthesis. We con-

sidered experimenters to have demonstratedthat synthesis was necessary in a particular caseif they conducted a direct comparison of syn-thesized and isolated conditions (e.g., via amultielement or reversal design) and found thatdifferentiation occurred or treatment was effec-tive when and only when EOs or whole contin-gencies were synthesized. Such directcomparisons occurred in 8% of all synthesizedFAs and 22% of all synthesized treatments. Forthe subset of applications in which synthesizedand isolated conditions were directly compared(n = 53), 80% found that the synthesis of vari-ables was necessary to produce a differentiatedFA or efficacious treatment.As an example, Mueller et al. (2005) con-

ducted a multielement SCA that included anescape-to-attention condition, an escape-onlycondition, and a control condition. Problembehavior reliably occurred in the escape-to-attention condition but was not differentiatedin the escape-only condition. We may thereforeconclude that a synthesis of escape and atten-tion was necessary to obtain a differentiatedFA, given the conditions selected by theseexperimenters. As another example, Sarnoet al. (2011) conducted SCAs with the samethree conditions with three participants, andalthough problem behavior occurred at thehighest rates in the escape-to-attention condi-tion for each participant, the escape-only condi-tion was differentiated as well. This indicatesthat the synthesis of escape and attention wasnot necessary to obtain a differentiated

FA. However, Sarno et al. also used a reversaldesign to compare treatment conditions withescape-to- attention and escape-only and foundthat problem behavior was reduced and appro-priate engagement was increased only whenboth reinforcers were synthesized.Slaton et al. (2017) reported similar results

for two participants (Emily and Jeff ): both anSCA and an isolated FA were differentiated forthese participants, suggesting that a synthesis ofreinforcers was not necessary to obtain differen-tiation. A multielement treatment comparison,however, indicated that FCT was effective onlywith the synthesized contingency and not withthe isolated reinforcer. The data reported bySarno et al. and Slaton et al. are noteworthybecause they illustrate the fact that synthesismay still be critical even when the FA suggestsit is not (i.e., a differentiated FA with isolatedreinforcers might still require a treatment withsynthesized reinforcers). As a fourth example,Fisher et al. (2016) compared SCAs and iso-lated FAs for five participants, similar to Slatonet al. Problem behavior was differentiated inboth FAs for four out of five participants, sug-gesting that synthesis was not necessary toobtain differentiation. However, unlike Sarnoet al. and Slaton et al., Fisher et al. did notinclude a comparative treatment analysis, whichmeans we cannot determine whether synthesiswould have been a necessary component ofeffective treatment in those cases.There were several ways in which experi-

menters arranged conditions to compare theinfluence of isolated and synthesized compo-nents. The examples of Mueller et al. (2005)and Sarno et al. (2011) described above dem-onstrate the most common arrangement:A synthesized test condition was compared toone in which a single reinforcer was provided(e.g., escape + attention vs. escape onlyvs. attention only) in a multielement design.Most synthesized FAs that included direct com-parisons of isolated and synthesized variablesused this arrangement (91%), but there are

957SYNTHESIS REVIEW

some methodological variations worth noting.Several authors reported FAs in which a synthe-sized test condition was compared to condi-tions in which all but one of the reinforcerswere present. For example, participant Gail inHanley et al. (2014) experienced a SCA with acombination of attention and tangibles. Toevaluate these reinforcers separately, experi-menters arranged a multielement FAs with atest condition in which toys were withheld butattention was continuously available and a sec-ond test condition in which attention was with-held but toys were continuously available. Thiscreated a context in which only one of the twoEOs was operating at any given time. This typeof isolated EO condition has also been reportedin at least four other studies (Call et al., 2005;Dolezal & Kurtz, 2010; Ghaemmaghami et al.,2015; Santiago et al., 2016). In each of thesecases, the isolated EO condition produced zeroor near-zero rates of problem behavior, indicat-ing one of two things: either none of the EOsby themselves were sufficiently evocative, or thepresence of reinforcers associated with otherEOs effectively competed with the single EOpresented. In addition to demonstrating thatproblem behavior depended on the interactionbetween EOs, these experimenters also demon-strated some of the boundary conditions underwhich stimuli did and did not function as rein-forcers (e.g., Hanley et al. demonstrated thatattention did not function as a reinforcer forGail in the context of preferred toys).As another methodological variation, two

studies reported conditions in which a singlereinforcer was delivered following problembehavior or an appropriate mand, and otherreinforcers were then delivered if problembehavior persisted during that reinforcementinterval (Ghaemmaghami et al., 2015; Payneet al., 2014). For example, Payne et al. (2014)conducted an SCA (with participant Samantha)in which tangible reinforcement was provided,and if problem behavior persisted during thetangible interval, attention was then provided as

well. They compared this to a control conditionin which noncontingent attention was providedduring the tangible reinforcement interval.Ghaemmaghami et al. (2015) reported an SCAin which attention, tangibles, and escape werecombined; treatment began by teaching a mandfor only one of these reinforcers (escape). Ifproblem behavior occurred during the escapeinterval, the other reinforcers (attention, tangi-bles) were provided. Both experimenters dem-onstrated that problem behavior persisted in thepresence of a single reinforcer and was elimi-nated only when subsequent reinforcers werealso provided. The logic is that if problembehavior persists in the presence of a putativereinforcer, it may not be maintained by thatsingle reinforcer (e.g., Roane, Lerman, Kelley, &Van Camp, 1999).Falcomata, Muething, Gainey, Hoffman,

and Fragale (2013) described a way of evaluat-ing individual reinforcers in a synthesized con-tingency during treatment (rather than duringthe FA). These experimenters initially taughtan omnibus mand that produced access to mul-tiple reinforcers that were each detected indi-vidually in an isolated FA. Followingacquisition of the omnibus mand, they taughtspecific mands for each individual reinforcer,and found that mands for some reinforcers(e.g., escape, tangible items) were consistentlyemitted, but mands for other reinforcers(e.g., attention) were rarely emitted. A plausibleinterpretation of these results is that escape andtangible items were functional reinforcers forproblem behavior, but attention was not. Thisexample is important as a model for evaluatingthe role of individual reinforcers because con-ducting this evaluation during treatment(instead of during the FA) allows for treatmentto begin immediately once the FA is concluded.In some cases, this may be preferable to delay-ing treatment while additional analyses are con-ducted to tease out the role of each reinforcer.A final example of comparative analyses

between synthesized and isolated reinforcers

JESSICA D. SLATON and GREGORY P. HANLEY958

worth noting is found in Call and LomasMevers (2014). These experimenters directlycompared an SEOA condition, SCA condition,and isolated reinforcer condition in a multiele-ment design. In the SEOA condition, demandswere presented while tangible items wererestricted; problem behavior produced escapeonly. In the SCA condition, the same synthe-sized EOs were programmed, but problembehavior produced both reinforcers (escape totangibles). In the isolated escape condition,demands were presented and problem behaviorproduced escape. All three conditions were dif-ferentiated; however, these authors also evalu-ated within-session patterns of responding todetermine whether problem behavior persistedduring the reinforcer interval (see also Jesselet al., 2016; Roane et al., 1999). Within-session analyses showed that problem behaviorpersisted during the reinforcer interval of theSEOA condition (when escape was providedbut the tangible EO remained in place) and theisolated escape condition (in which tangibleswere never provided). By contrast, problembehavior immediately ceased and did not occurduring the reinforcer interval of the SCA condi-tion in which both reinforcers were provided,suggesting that tangible items were relevant toproblem behavior. Treatment data confirmedthis interpretation.Treatment efficacy. Identifying the controlling

variables for problem behavior is a desirableoutcome not for the sake of differentiation inand of itself, but because differentiation pro-vides information from which to design treat-ment. Treatment effect size is thus animportant criterion by which to evaluate themerits of synthesized FAs, and perhaps a morepragmatic criterion than that of differentiation(i.e., a differentiated FA has practical value if itproduces an effective treatment, and much lessvalue if that treatment fails). Table 5 reports asummary of two different measures of treat-ment effect size (MBLR and PND) for the finalphase of all synthesized treatments and any

comparative isolated treatments. AverageMBLR across all synthesized treatment applica-tions was 90.2%, compared to -0.3% across allisolated treatment comparisons. An indepen-dent samples t-test found this difference to bestatistically significant (p < 0.01; t (26) = 7.7).Measuring treatment effects using PNDrevealed a similar pattern. Average PND acrossall synthesized treatment applications was88.6%, compared to 43.3% for isolated treat-ment applications; an independent samples t-test found this difference to be significant aswell (p < .01; t (32) = 8).Figure 4 presents MBLR values for each

individual application, organized first bywithin-subject comparisons and then by syn-thesized applications without an isolated com-parison.4 Most synthesized treatmentapplications (89%) achieved a MBLR of 80%or higher; over half (57%) achieved a reductionof 95% or higher. By contrast, 11% of isolatedtreatment applications achieved a MBLR of80% or higher; 7% achieved a reduction of

Table 5Treatment Efficacy

Type of Treatment PNDa MBLRb

Synthesized (n = 109) M = 88.6 M = 90.2Isolated (n = 27) M = 43.3 M = -0.3

Note. PND = percentage of non-overlapping datapoints; MBLR = mean baseline reduction.a PND was calculated by dividing the number of treat-ment points that fell below the lowest baseline pointby the total number of treatment points and multiply-ing by 100.

b MBLR was calculated by subtracting that mean treat-ment score from the mean baseline score, dividingthat number by the mean baseline score, and multiply-ing by 100.

4The number of applications evaluated for MBLR andPND is less than the total number of treatment applica-tions reviewed because we evaluated treatment effectsusing only the final phase of each treatment (e.g., a treat-ment that was conducted in a clinic and then extended tothe home environment would be counted as two applica-tions; only the latter was evaluated for MBLR and PND).

959SYNTHESIS REVIEW

95% or higher. Of the 97 synthesized treatmentapplications that achieved 80% MBLR or higher,the majority of them (n = 61; 63%) also includedschedule thinning (e.g., Ghaemmaghami et al.,2016; Strohmeier et al., 2016) or schedule thin-ning plus social validity measures (e.g., Jesselet al., 2018). For example, Ghaemmaghamiet al. (2016) gradually increased the number ofdemands that participant Alex was required tocomplete before accessing the functional rein-forcers for his problem behavior, until he was reg-ularly complying with up to 50 demands over aperiod of approximately 10 min). There werethree treatment applications that compared syn-thesized versus isolated contingencies duringschedule thinning beyond the initial stages ofFCT; each of them demonstrated that schedulethinning was only successful in the synthesizedtreatment condition (one application in Lalli &Casey, 1996; two applications in Zangrilloet al., 2016).Several treatment applications are worth not-

ing because of the extended effects of synthe-sized contingencies (e.g., Hagopian et al.,2007; Hanley et al., 2014; Jessel et al., 2018;

Santiago et al., 2016). The synthesized treat-ments described by Hanley et al. (2014) andSantiago et al. (2016) all eliminated problembehavior, were generalized to other settings,and were socially validated by the parents ofthe children. Jessel et al. (2018) recentlyreported 25 synthesized FA and treatmentapplications in a consecutive controlled caseseries (similar to Hagopian, Rooker, Jessel, &DeLeon, 2013); these authors reported a meanMBLR of 99% across the final three treatmentdata points for these 25 consecutive cases.There were three instances in which an iso-

lated treatment comparison achieved MBLR ofat least 80% (two for participant Dylan andone for participant Chloe in Slaton et al.,2017), indicating that isolated and synthesizedtreatments were both effective in these cases.The fact that both treatments were effectivesuggests that the synthesized contingency wasnot necessary to obtain initial treatment effectsfor either participant; these applications repre-sent the only examples to date in which theinclusion of possibly unnecessary reinforcers inan SCA has been demonstrated.

10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

-500

-100

-80

-60

-40

-20

0

20

40

60

80

100

Synthesized Isolated

Within-subjectcomparisons

Applicationswithout comparisons

Treatment applications

Mea

n

bas

elin

e re

du

ctio

n

(%)

Figure 4. MBLR for all synthesized treatment applications and comparative isolated applications.

JESSICA D. SLATON and GREGORY P. HANLEY960

“Unplanned” synthesis. We identified a num-ber of articles (not included in the samples) inwhich the authors did not describe their condi-tions as including synthesis, but it was clearfrom carefully reading the Method sections thatthe test conditions in these FAs actuallyincluded synthesized reinforcers. For example, anumber of studies reported providing tangiblesor attention during the escape period of theescape condition (Asmus et al., 1999; Berg,Wacker, Harding, Ganzer, & Barretto, 2007;Harding, Wacker, Berg, Lee, & Dolezal, 2009;Schieltz et al., 2010). In other cases, demandswere presented during tangible or attentionconditions, indicating that multiple EOs werelikely salient and that problem behavior mayhave produced escape and attention or tangiblessimultaneously (Day, Horner, & O’Neill,1994; Jones, Drew, & Weber, 2000). Theseconditions were described as isolated reinforcerconditions (e.g., escape or attention), but thedetails reported in the Methods indicated thatsynthesized contingencies were operating. It isimportant to note that these papers were identi-fied outside of the search terms we describedabove; it is likely that there are more examplesof studies that have included synthesis withoutclearly labeling it.All of the studies with what might be

referred to as an “unplanned” synthesis wereconducted in homes or classrooms where it islikely that multiple events occurred togetherfollowing problem behavior. For example, theanalysis reported by Harding et al. (2009) wasconducted with a toddler in his bedroom withhis mother serving as the analyst. It is reason-able to assume that providing attention duringthe escape interval represents the way the par-ent naturally interacted with her child duringproblem behavior. Jones et al. (2000) con-ducted their analysis in a classroom during asummer program in which students wereengaged in academic instruction during most ofthe day; academic instruction is therefore likelythe context in which problem behavior

typically occurred. Although the authorsdescribed their test conditions as involving sin-gle reinforcers, the exigencies of the naturalconditions under which they were analyzingbehavior appears to have occasioned a relianceon synthesized contingencies.

DISCUSSION

Prevalence and Features of Synthesized FAsand TreatmentsSynthesized FAs have been referred to

broadly as modified FAs (e.g., Adelinis &Hagopian, 1999) or have been named based onsome feature of the synthesized contingency.For example, Hagopian et al. (2007) calledtheir analysis an interruption analysis; Fisheret al. (1998) used the name analysis of “don’t”requests; Mueller et al. (2005) described theiranalysis as an FA with an escape-to-attentioncondition. The myriad of terms used todescribe synthesized FAs is likely one reasonthat about 40% of the articles we identifiedwere found by reviewing reference lists of arti-cles returned by our search terms and not bythe search terms themselves (see Figure 2). Thisis a limitation of this review and of the litera-ture itself and reflects the need for consistentlanguage to describe this subset of FAs. Hanleyet al. (2014) was the first publication to applythe descriptor synthesized to a procedure inwhich multiple reinforcers were combined in asingle test condition, and to suggest the generalrelevance of synthesis in FAs. Although thestudies we reviewed share the key componentof synthesis, their features and outcomes havenot been collectively described and interpretedtogether through a common lens. Synthesis is anuanced feature of FAs and treatments; tactingits presence is important because it ties togethera group of studies that otherwise appear unre-lated, and it places them within the same con-ceptual framework. To illustrate, one finding ofour current review is that the use of synthesisin FAs and treatments is not new; the earliest

961SYNTHESIS REVIEW

example we reviewed was published in 1995(O’Reilly, 1995; an SEOA evaluating attentionand escape in the context of sleep deprivation).The novelty of these approaches lies not withthe methods per se but with the encompassinglabel applied to these arrangements and the factthat researchers have begun to examine the rel-ative benefits of synthesized and isolated con-tingencies (e.g., Call & Lomas Mevers, 2014;Fisher et al., 2016; Ghaemmaghami et al.,2015; Hanley et al., 2014; Santiago et al.,2016; Slaton et al., 2017; Zangrilloet al., 2016).Beavers et al. (2013) reported that 59.7% of

all FA applications were conducted in highlyspecialized settings (inpatient units and institu-tions). By contrast, this type of setting was thecategory least reported for synthesized FAs andtreatments. It is possible that natural, lessrestrictive settings (e.g., homes, schools, clinics)represented the majority of all synthesized FAand treatment applications because these loca-tions are likely more conducive to analyzingcombinations of variables that typically co-occur in the course of daily life (and perhapsless conducive to isolating individual rein-forcers). For example, a child who engages inproblem behavior at home when asked to getdressed in the morning may temporarily escapethis demand and easily access any number oftoys that happen to be available in his bed-room. Conducting an FA to isolate escape andtangibles in this context could pose some prac-tical challenges (i.e., access to toys would needto be blocked or otherwise prevented duringthe escape condition). Similarly, it is possiblethat the smallest percentage of applicationswere reported on inpatient units because thesesettings often have the time and resources avail-able to conduct extended analyses in modifiedenvironments where reinforcers are more easilycontrolled (e.g., session rooms). It is also worthnoting, however, that the population served oninpatient units is generally not representative ofthe broader population of individuals who

engage in problem behavior. The successfulimplementation of synthesized FAs in naturalsettings is important to note because surveys ofFA usage among practitioners have indicatedthat most practitioners do not conduct FAsbefore treating problem behavior; the reasonsprovided generally relate to effort, time, andlack of resources (Ellingson, Miltenberger, &Long; 1999; Oliver, Pratt, & Normand, 2015;Roscoe, Phillips, Kelly, Farber, & Dube,2015). The successful implementation of syn-thesized FAs in natural settings suggests thatthey may be a viable option for practitionerswho work in these settings.The overwhelming majority of synthesized

FAs included synthesized response topographies(i.e., targeted two or more topographies forreinforcement in the FA). Although Beaverset al. (2013) cautioned against reinforcing mul-tiple topographies of problem behavior, theyalso found that the majority of published FAsthey reviewed (75.9%) targeted reinforcementfor multiple topographies of problem behavior.Thus, the tendency to include multiple topog-raphies appears to be relatively common in theFA literature, regardless of whether isolated orsynthesized contingencies are used. The inclu-sion of precursors does not seem to be particu-larly problematic either, as a number ofresearchers have demonstrated that precursorsand problem behavior are likely maintained bythe same reinforcers (Borrero & Borrero, 2008;Fritz, Iwata, Hammond, & Bloom, 2013;Herscovitch, Roscoe, Libby, Bourret, &Ahearn, 2009; Langdon, Carr, & Owen-DeS-chryver, 2008; Najdowski, Wallace, Ellsworth,MacAleese, & Cleveland, 2008; Smith &Churchill, 2002). It should be noted, however,that the functional equivalence of precursorand problem behavior has not been demon-strated yet within the synthesized FA literature;this is an important area of future research.It is also important to note that authors do

not typically report which individual topogra-phies occurred during the FA (i.e., data are

JESSICA D. SLATON and GREGORY P. HANLEY962

typically expressed as a combined measure ofproblem behavior; cf. Beavers et al., 2013),which means it is unknown whether all topog-raphies that were targeted for reinforcementactually contacted reinforcement, whether asubset of topographies occurred, or whether asingle topography occurred. Alternatively, in anFA designed to evaluate a single topography, itis possible that other topographies could occurwithin close temporal proximity to the one tar-get response, resulting in multiple topographies(including those not targeted for reinforcement)contacting reinforcement. For example, Slatonet al. (2017) reported that precursors were rein-forced during isolated FAs for some participantsbecause they occurred within 2 s of problembehavior, even though precursors were notscheduled for reinforcement. This lack of clar-ity regarding which and how many topogra-phies were reinforced in an FA appearscommon across all types of FAs. Authors whoreport FAs (either synthesized or isolated) maywish to consider reporting exactly which topog-raphies occurred during the FA; this informa-tion would allow future reviews of FA literatureto more clearly evaluate the extent to whichisolated versus synthesized topographies arebeing reinforced in FAs.With regard to the combinations of rein-

forcers evaluated in SCAs, we found nine gen-eral combinations (see Table 3). When viewedthrough the lens of broad reinforcer categoriessuch as attention, escape, and tangibles, thereare a limited number of different combinationsof reinforcers that may be synthesized. How-ever, when examined more closely, qualitativevariations in these general classes of reinforce-ment are evident and the number of differentpossible synthesized contingencies is wide. Asan example, Jessel et al. (2016) reported27 unique contingencies across 30 differentSCAs (see their Table 2). The only repeatedcontingency in that sample was escape fromadult-directed to child-directed activity. We donot know to what extent the specific adult- or

child-directed activities varied across those par-ticipants; it is likely that each application wasunique, even though the general contingencywas the same. It would be inaccurate to charac-terize SCAs as representing a small range ofpossible reinforcer combinations; the qualitativenature of the reinforcers included in SCAs isoften distinct. For instance, different synthe-sized contingencies may include attention, butone may be attention in the form of engagingin child-directed pretend play (e.g., participantAlex in Jessel et al., 2016), and one may beattention in the form of chatting about pre-ferred conversation topics (e.g., participantKaren in Santiago et al., 2016). To say thatproblem behavior for both individuals is main-tained by attention (in combination with otherreinforcers) would be accurate and yet it is pos-sible that such a description would lack thenecessary detail to replicate the analysis ordesign a treatment that incorporates the func-tional reinforcers for problem behavior. Theextent to which providing technologicaldescriptions of synthesized reinforcers based onnuanced and qualitative details (e.g., escapefrom independent academic work to child-directed play with arts and crafts materials) ismore beneficial than providing such detailsbased on generic reinforcer categories(e.g., escape to tangibles) remains an empiricalquestion to be answered.A second important point regarding rein-

forcer combinations is that authors did notreport reinforcer consumption during FAs,which means we do not know to what extentprogrammed and unprogrammed reinforcerswere actually experienced. This is true of syn-thesized FAs and other FAs. Consider, forexample, an SCA that is designed to provideescape, attention, and tangibles. This does notnecessarily mean that all three reinforcers wereconsumed by the participant. It is possible thatescape and attention were the only reinforcersexperienced during the entire analysis (i.e., theparticipant declined to engage with the tangible

963SYNTHESIS REVIEW

items, or chose to continue engaging with thedemand presented). Similarly, consider an iso-lated escape condition in which escape is pro-vided following problem behavior, and theindividual consistently engages in stereotypyduring the escape interval. This could reason-ably be characterized as an escape-to-stereotypycondition; describing it simply as an escapecondition would obscure the fact that we donot know the extent to which problem behav-ior is maintained by escape, access to stereo-typy, or both. Thus, it is possible that aparticipant in an SCA may not experience allreinforcers in the synthesized contingency; like-wise, it is possible that a participant in an iso-lated FA may experience synthesizedreinforcers. Just as authors may wish to beginreporting which topographies actually occurredduring an FA, we suggest that there may alsobe benefits to reporting which reinforcers wereconsumed during an FA. This would allowfuture reviews of FA literature to more accu-rately describe the extent to which synthesizedreinforcers are consumed during FAs.

The Value of Naming SynthesisThere are numerous variations to types of

FAs, as well as their measurement and design.For example, in addition to the FA modelreported by Iwata et al. (1982/1994), authorshave reported brief FAs (e.g., Derby et al.,1992; Northup et al., 1991), latency FAs(e.g., Thomason-Sassi et al., 2011), precursorFAs (e.g. Smith & Churchill, 2002), and trial-based FAs (e.g. Sigafoos & Saggers, 1995).These variations are each named and identifiedseparately because their procedures presumablyvary enough to warrant distinction, andbecause it is easier to name a thing than todescribe it by its features (e.g., it easier to saybrief FA than an FA in which a single session isconducted in each test condition and often a con-tingency reversal is included). If we view all FAsas falling somewhere on the continuum

between isolated and synthesized, a questionthat may arise is whether it is even necessary toidentify SCAs and SEOAs as specific subcate-gories of FAs (given that most FAs likelyinclude some type of synthesis, even if it is asynthesis of topographies only). We argue thatthis distinction is justified because the presenceor absence of synthesis in an FA, and the par-ticular type of synthesis, directly influences theconclusions we may draw about the variablesresponsible for problem behavior; therefore, itis helpful to have a specific name by which torefer to this subset of FAs.Identifying SEOAs as one variation in FA