NATO · Bukovski during a visit to the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia* on 29 August to...

Transcript of NATO · Bukovski during a visit to the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia* on 29 August to...

InterviewwithMartti Ahtisaaripages 24-25

Military reformin Central andEastern Europepages 30-33

NATONATO’s evolving partnerships

DE

PO

T A

NT

WE

RP

EN

X

NATOreviewnorth atlantic treaty organisation

belgiumcanada

czech republicdenmark

francegermany

greecehungaryiceland

italyluxembourgnetherlands

norwaypoland

portugalspainturkey

united kingdomunited states

AUTUMN 2001

NATO’s evolving partnerships

NATOPublished under the authority of theSecretary General, this magazine isintended to contribute to a constructivediscussion of Atlantic issues. Articles,therefore, do not necessarily representofficial opinion or policy of membergovernments or NATO.

EDITOR : Christopher BennettASSISTANT EDITOR : Vicki NielsenPRODUCTION ASSISTANT: Felicity BreezeLAYOUT : NATO Graphics Studio

Publisher:Director of Information and PressNATO, 1110 Brussels, Belgium

Printed in Belgium by Editions Européennes© NATO

[email protected]@hq.nato.int

Articles may be reproduced, after permission hasbeen obtained from the editor, provided mentionis made of NATO Reviewand signed articles arereproduced with the author’s name.

NATO Review is published periodically in English,as well as in Czech, Danish (NATO Nyt), Dutch(NAVO Kroniek), French (Revue de l’OTAN),German (NATO Brief), Greek (Deltio NATO),Hungarian(NATO Tükor), Italian (Rivista dellaNATO), Norwegian (NATO Nytt), Polish (PrzegladNATO), Portuguese (Noticias da OTAN), Spanish(Revista de la OTAN)and Turkish (NATO Dergisi).One issue a year is published in Icelandic (NATOFréttir) and issues are also published in Russianand Ukrainian on an occasional basis.

NATO Reviewis also published on the NATO website at: www.nato.int/docu/review.htm

Hard copy editions of the magazine may beobtained free of charge by readers in the follow-ing countries from the addresses given below:CANADA :Foreign Policy Communications DivisionDepartment of Foreign Affairs and Int’l Trade125 Sussex DriveOttawa, Ontario K1A 0G2UNITED KINGDOM :Communication Planning UnitMinistry of DefenceRoom 0370 Main BuildingLondon SW1A 2HBUNITED STATES:NATO Review— US Mission to NATOPSC 81 Box 200 — APO AE 09724

Requests from other countries or for other NATO publications should be sent to:NATO Office of Information and Press1110 Brussels, BelgiumFax: (32-2) 707 1252E-mail: [email protected]

Every mention in this publication of the formerYugoslav Republic of Macedonia is marked by anasterisk (*) referring to the following footnote:Turkey recognises the Republic of Macedonia withits constitutional name.

NATO review2 Autumn 2001

contentsNATOreview

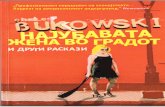

ON THE COVER

Allied and Partner soldiersparading together.

© N

ATO

FOCUS ON NATO4Alliance news in brief

NATO’S EVOLVING PARTNERSHIPS

6Building security through partnershipRobert Weaver analyses the evolution of NATO partnerships.

10Getting Cinderella to the ballRobert E. Hunter examines thepotential of the Euro-AtlanticPartnership Council.

13Promoting regional securityJames Appathurai examines howNATO promotes regional securitycooperation.

16Partnership in practice:Georgia’s experienceIrakli Menagarishvili describesGeorgia’s relationship with NATO.

ESSAY

18Imagining NATO 2011Michael Rühle imagines how theAlliance and the Euro-Atlanticsecurity environment might look inten years.

FEATURES

22Monitoring contamination inKazakhstan

23Easing the transition to CivvyStreet

INTERVIEW

24Martti Ahtisaari:international mediator

Autumn 2001 NATO review 3

fore

wor

d During the production of this issue of NATO Review,the United States suffered a devastating terrorist attack,the effects of which have been felt around the world. Thereaction of America’s Allies to the barbaric attacks of 11September was immediate: total solidarity with the UnitedStates in its time of need. As a profound symbol of thatsolidarity, on 12 September, NATO’s members agreed that,if it were determined that this attack had been directedfrom abroad against the United States, it should be regard-ed as an action covered by Article 5 of the WashingtonTreaty, which states that an attack against one or moreAllies shall be considered an attack against them all. On 2October, the US government confirmed that the attackshad indeed been launched from abroad, by terrorists fromOsama Bin Laden’s al-Qaida organisation.

NATO’s essential foundation – its bedrock – has alwaysbeen Article 5, the commitment to collective defence. Ofcourse, this commitment was first entered into in 1949, invery different circumstances. But it remains equally validand essential today, in the face of this new threat. With thedecision to invoke Article 5, NATO’s members demon-strated, once again, that the Alliance is no simple talkingshop. It is a community of nations, united by its values, andutterly determined to act together to defend them.

On 12 September, it was also demonstrated that theEuro-Atlantic community today is much broader than the19 NATO members. Within hours of NATO’s historicdecision, the 46 member countries of the Euro-AtlanticPartnership Council – from North America, Europe andCentral Asia – issued a statement in which they agreedthat these acts were an attack not only on the UnitedStates, but on our common values. In the EAPC state-ment, the 46 countries also pledged to undertake all effortsneeded to combat the scourge of terrorism.

It is too early to say what role NATO and its members,or the EAPC, will play in the coming international strug-gle against the scourge of terrorism. That struggle will belong and sometimes difficult. It will require all the tools atour disposal, political, economic, diplomatic as well as mil-itary. And it will need the active engagement of the widestpossible coalition of countries, all working towards com-mon goals. The solidarity and determination displayed inBrussels on 12 September, by the North Atlantic Counciland the EAPC, are a vital first step. They show the practi-cal importance of NATO’s partnerships and underline thetimeliness of this issue of NATO Review.

Lord Robertson

Volume 49Autumn 2001

REVIEW

26The new Macedonian questionChristopher Bennett reviews recentliterature on the former YugoslavRepublic of Macedonia.*

SPECIAL

28Educating a new eliteColonel Ralph D. Thiele describeshow the NATO Defense Collegecaters for citizens of Partner countries.

MILITARY MATTERS

30Reform realitiesChris Donnelly examines militaryreform in Central and EasternEurope.

STATISTICS

34Defence expenditure and size ofarmed forces of NATO andPartner countries

NATO Secretary General LordRobertson visited Berlin, Germany,on 20 and 21 September to attend theNATO Review conference, an annualevent to discuss the future of theAlliance, and meet ChancellorGerhard Schröder, Foreign MinisterJoschka Fischer and other politicalleaders.

Armitage briefs

US Deputy Secretary of State RichardArmitage visited NATO on 20September to brief Lord Robertsonand the North Atlantic Council on thestate of investigations into the terror-ist attacks of 11 September.

Follow-on forceOn 19 September, President BorisTrajkovski of the former YugoslavRepublic of Macedonia* askedNATO to deploy a reduced, follow-onforce in his country after the end ofOperation Essential Harvest on 26September.

Between 17 and 22 September, fourNATO members and five Partnersparticipated in CooperativeEngagement 2001, the first maritimeNATO/Partnership-for-Peace exerciseto take place in Slovenia, at Ankarannear Koper.

Seven NATO members and threePartners participated in CooperativePoseidon, the second phase of a sub-marine safety exercise, which tookplace in Bremerhaven, Germany,between 17 and 21 September. Theexercise was also attended byobservers from seven Mediterra-nean Dialogue countries.

Military personnel from nine NATOand 13 Partner countries took part inCooperative Key 2001, an exercise in

peace-support operations, whichtook place in Plovdiv, Bulgaria,between 11 and 21 September.Representatives of the office of theUN High Commissioner for Refugeesand several non-governmental organ-isations also participated.

Between 10 and 21 September, par-ticipants from seven NATO membersand 13 Partner countries took part inCooperative Best Effort 2001 atZeltweg Airbase, Austria, an exercisedesigned to train participants inpeace-support skills.

German General Dieter Stöckmannsucceeded UK General Sir RupertSmith as Deputy Supreme AlliedCommander Europe at a ceremony atSupreme Headquarters, AlliedPowers Europe (SHAPE) in Mons,Belgium, on 17 September.

Lord Robertson visited Skopje, theformer Yugoslav Republic ofMacedonia,* on 14 September toconsult with President BorisTrajkovski and his government andreview progress of OperationEssential Harvest.

Three minutes silenceOn 13 September, NATO staff joinedmillions of people across Europe inobserving three minutes silence forthe victims of the 11 September ter-rorist outrage and their families.

NATO and Russia expressed theirdeepest sympathy with the victims ofthe 11 September terrorist attacks inNew York and Washington DC andtheir families and pledged to intensifycooperation to defeat terrorism at ameeting of the NATO-RussiaPermanent Joint Council on 13September. Similar sentiments wereexpressed at extraordinary meetingsof the NATO-Ukraine Commissionand the Euro-Atlantic PartnershipCouncil.

New UK ambassadorAmbassador Emyr Jones Parry suc-ceeded Ambassador David Manningas the permanent representative ofthe United Kingdom to NATO on 13September. Ambassador Parry, 53, isa career diplomat and was politicaldirector of the Foreign andCommonwealth Office from July1998 until August 2001.

Article 5On 12 September, NATO ambassa-dors agreed that if the 11 Septemberterrorist attack was directed fromabroad, it would be considered as anattack on all NATO Allies, thus invok-ing Article 5 of the WashingtonTreaty, NATO’s founding charter, forthe first time in the Alliance’s history.

On 11 September, Lord Robertsonand the North Atlantic Council con-demned terrorist attacks on innocentcivilians in the United States andexpressed their deepest sympathyand solidarity with the American peo-ple.

On 7 September, Lord Robertsonattended the last day of a three-daysymposium in Oslo, Norway, whichfocused on technological, industrialand scientific aspects of adapting totoday’s transformed security environ-ment. The event was hosted jointly bythe Supreme Allied Commander,Atlantic (SACLANT), the NorwegianDefence Command and the US JointForces Command.

New US ambassador

Ambassador Nicholas Burns suc-ceeded Ambassador AlexanderVershbow as permanent representa-tive of the United States to NATO on4 September. Ambassador Burns, 45,was formerly US ambassador toGreece from 1997 until July 2001.

Between 1995 and 1997, he wasspokesman of the US StateDepartment.

A live-flying exercise to train airforces in tactical air operations,including the suppression of enemyair defences and electronic warfare,took place between 3 and 14September from Main Air Station inØrland, Norway. Air Meet 2001involved air forces from 13 NATOmember countries and was conduct-ed by the headquarters of Allied AirForces North, based at Ramstein,Germany.

Lord Robertson met President BorisTrajkovski, Prime Minister LjubcoGeorgievski, Interior Minister LjubeBoshkovski, Foreign Minister IlinkaMitreva and Defence Minister VladoBukovski during a visit to the formerYugoslav Republic of Macedonia*on 29 August to assess progressmade by NATO troops in collectingweapons from ethnic Albanian rebels.

Disarming rebels

Operation Essential Harvest waslaunched on 22 August, two monthsafter the government of the formerYugoslav Republic of Macedonia*requested NATO assistance to restorepeace and stability in its country. The30-day mission, which effectivelystarted on 27 August, was to disarmethnic Albanian rebels and involvedsome 3,500 troops, with logisticalsupport.

The situation in the former YugoslavRepublic of Macedonia* dominatedthe regular joint meeting of the NorthAtlantic Council and the EuropeanUnion’s Political and SecurityCommittee, held in Brussels,Belgium, on 22 August.

NATO review4 Autumn 2001

FOCUS ON NATO

Indicted war criminal Dragan Jokic, aBosnian Serb implicated in the 1995Srebrenica massacre and attacks onUN observation posts, surrendered toSFOR troops on 15 August.

The headquarters of Task ForceHarvest deployed in the formerYugoslav Republic of Macedonia*on 15 August — two days after thesigning of a political frameworkagreement to provide for internalreforms and allow NATO-led troopsinto the country to disarm ethnicAlbanian rebels — to assess the situ-ation and prepare the launch ofOperation Essential Harvest.

Vidoje Blagojevic, a former BosnianSerb commander indicted for warcrimes, was detained on 10 Augustand transferred to the InternationalWar Crimes Tribunal in The Hague.

Flood preparationsWork on a pilot project to improveflood preparedness and response inthe Tisza river area in Ukraine beganin September. The project is beingdeveloped in the context of the NATO-Ukraine work programme for 2000.

Lord Robertson joined EU HighRepresentative for Common Foreignand Security Policy Javier Solanaand the OSCE Chairman-in-Office,Romanian Foreign Minister MirceaGeoana, in Skopje, the formerYugoslav Republic of Macedonia* on26 July for talks with governmentleaders and political parties to rein-vigorate talks aimed at ending fivemonths of violence.

Lithuanian Prime Minister AlgirdasBrazauskas met Lord Robertson atNATO on 24 July.

On 19 July, the Military Committee,NATO’s highest military authority, and

its chairman, Admiral GuidoVenturoni, visited the regional south-ern command, Allied Forces SouthernEurope (AFSOUTH), which is respon-sible for all NATO-led operations inthe Balkans.

Serbian Deputy Prime MinisterNebosja Covic and Yugoslav ForeignMinister Goran Svilanovic met LordRobertson and addressed the NorthAtlantic Council on 18 July.Discussions focused on develop-ments in southern Serbia andKosovo.

New NATO DeputySecretary General

Ambassador Alessandro MinutoRizzo succeeded Ambassador SergioBalanzino as NATO Deputy SecretaryGeneral on 16 July. AmbassadorRizzo is an Italian career diplomat andwas previously his country’s perma-nent representative to the EuropeanUnion’s Political and SecurityCommittee.

Lord Robertson and the 19 NATOambassadors visited Albania andBosnia and Herzegovina on 12 and13 July for wide-ranging discussionswith government leaders.

Current Euro-Atlantic security issueswere discussed at a five-day meetingorganised by the NATO Parliamen-tary Assembly for young and newly-elected parliamentarians from NATOand Partner countries, held inBrussels, Belgium, between 9 and 13July.

Romanian President Ion Iliescu andForeign Minister Mircea Geoana metLord Robertson on 9 July at NATO todiscuss the situation in the Balkansand Romania’s cooperation withNATO.

On 6 July, the day after a cease-firebetween the government and ethnicAlbanian rebels in the formerYugoslav Republic of Macedonia*was signed, Foreign Minister IlinkaMitreva came to NATO to meet LordRobertson.

Lord Robertson visited Kyiv,Ukraine, on 4 and 5 July, where hemet President Leonid Kuchma,Prime Minister Anatolyi Kinakh,Foreign Minister Anatolyi Zlenkoand Defence Minister OlexandrKuzmuk, as well as other key figures.He also addressed a Partnership forPeace symposium organised bySACLANT.

A ceremony to mark the inaugurationof a project aimed at destroyingAlbania’s stockpile of 1.6 million anti-personnel mines — as requiredunder the Ottawa Convention pro-hibiting the use, stockpiling, produc-tion and transfer of anti-personnelmines — took place at Mjekës, southof the capital Tirana, on 29 June. Thisis the first demilitarisation project tobe implemented under a Partnershipfor Peace Trust Fund set up for thispurpose in 2000.

Essential HarvestOn 29 June, the North AtlanticCouncil approved Essential Harvest,an operation plan drawn up bySHAPE, for the possible deploymentof NATO troops to the formerYugoslav Republic of Macedonia,*at the request of the government, tohelp disarm ethnic Albanian groups.The plan would be implemented oncondition that the parties pursuepolitical dialogue and end hostilities.

Moldovan President Vladimir Voranvisited NATO on 28 June, where hemet Lord Robertson and signed anagreement, which will enable NATOexperts to provide material assis-tance and training to ensure theimplementation of a Partnership forPeace Trust Fund project aimed atthe safe destruction of highly corro-sive rocket fuel, as well as anti-per-

sonnel landmines and surplus muni-tions.

UN Special Representative to KosovoHans Haekkerup briefed NATOambassadors on the situation in theprovince and preparations forupcoming elections there at NATO on26 June.

Polish President AleksanderKwasniewski visited SHAPE in Mons,Belgium, on 21 June, where he metthe Supreme Allied CommanderEurope, US General Joseph W.Ralston.

US visitDuring a trip to the United Statesfrom 19 to 22 June, Lord Robertsongave a speech to the Chicago Councilfor Foreign Relations, before travel-ling to Washington to meet NationalSecurity Advisor Condoleezza Rice,Secretary of State Colin Powell andSecretary of Defense DonaldRumsfeld. He then attended theannual seminar organised bySACLANT in Norfolk, Virginia, whichthis year focused on NATO’s militarycapabilities.

Between 18 and 29 June, 15 NATOcountries took part in Clean Hunter2001, a live-flying exercise overnorthern Europe and northernFrance. This annual event involvesthe headquarters of Allied Air ForcesNorth and its subordinate combinedair operations centres in exercisesaimed at maintaining effectiveness inplanning and conducting coordinatedlive air operations.

Autumn 2001 NATO review 5

For more information, see NATO Update at: www.nato.int/docu/update/index.htm

FOCUS ON NATO

NATO review6 Autumn 2001

In addition to hosting the EAPC, a dynamic, multilateral forum for the discussion and promotion ofsecurity issues, NATO is the focal point of a web of inter-locking security partnerships and programmes. TheAlliance is working via the Partnership for Peace to helpreform militaries and assist the democratic transition inmuch of former Communist Europe. Moreover, specialbilateral relations have been forged with both Russia andUkraine, the two largest countries to emerge out of the dis-integration of the Soviet Union. And a security dialogue isongoing with an ever increasing number of countries in theMediterranean region (see box on page 9).

Today, 27 Partners use this institution to consult regularly with the 19 Allies on issues encompassing allaspects of security and all regions of the Euro-Atlanticarea. In addition, Allied and Partner militaries exercise andinteract together on a regular basis. And some 9,000 sol-

Robert Weaver works on NATO enlargement and EAPCmatters in NATO’s Political Affairs Division.

W hen the 46 ambassadors of the Euro-AtlanticPartnership Council (EAPC) meet, they take itfor granted that they will be able to debate and

discuss the most pressing security issues of the day in anopen and constructive environment. But just a little overten years ago, diplomats from countries that belonged tothe Warsaw Pact – which represent close to half of today’sEAPC members – were unable even to enter NATO head-quarters. If they wished to deliver a message, they wereobliged to leave it at the front gate. This contrast illustratesthe evolution of Euro-Atlantic security in the past decadeand, above all, the way in which an Alliance strategy builtaround partnerships has altered the strategic environmentin the Euro-Atlantic area.

Building security through partnership

Robert Weaver analyses the evolution of NATO’s partnerships ten years after thecreation of the North Atlantic Cooperation Council.

© N

ATO

Historic event: the Soviet Union dissolved during the first meeting of the North Atlantic Cooperation Council in December 1991

diers from Partner countries, including about 4,000Russians, serve alongside their Alliance counterparts in theNATO-led peacekeeping operations in the Balkans.

Anyone predicting in 1991 the kind of evolution ofEuro-Atlantic security that has taken place over the pastdecade would likely have faced ridicule. At the time, withthe end of the Cold War, it was more fashionable for ana-lysts to predict the imminent demise of NATO or, in thewake of the Moscow coup of August 1991, a return to theconfrontational stances, which had characterised Europeanpolitics for the best part of half a century. Moreover, look-ing back, things could have gone horribly wrong. That theydid not is in large part because the Allies offered a “hand offriendship” to their former adversaries and is a tribute tothe partnership-building strategy, which NATO has pur-sued over the past decade.

At the end of the Cold War, NATO’s primary task was totry to overcome lingering misconceptions about what theAlliance stood for and how it operated. Explaining thatNATO was a defensive Alliance was critical. In London, inJuly 1990, NATO leaders decided to reduce the role ofnuclear weapons in the Alliance’s military strategy to thatof “weapons of last resort”. This move signalled NATO’sbenign intentions and was meant to deny the anti-reformforces in Moscow the pretext of an alleged “NATO threat”to crack down on the liberalisation process in central andeastern Europe. Beyond this, NATO needed to considerhow best to establish a genuine security relationship withthese countries, which would allow the Alliance actively toshape security developments. At NATO’s Rome Summit inNovember 1991, the Alliance proposed the creation of theNorth Atlantic Cooperation Council (NACC) as a forumfor a structured dialogue with former Warsaw Pact coun-tries.

The NACC met for the first time in December 1991 with16 Alliance and nine Partner countries in attendance. Suchwas the pace of change in Europe at the time that the meet-ing itself witnessed a historic diplomatic event. As the finalcommuniqué was being agreed, the Soviet ambassadorasked that all references to the Soviet Union be struck fromthe text. The Soviet Union had dissolved during the meet-ing with the result that, in future, he could only representthe Russian Federation. In March 1992, a further ten newlyindependent states from the former Soviet Union joined theNACC. Albania and Georgia became members in June ofthat year.

In the immediate post-Cold War period, NACC consulta-tions focused on residual Cold War security concerns, suchas the withdrawal of Russian troops from the Baltic States.Meanwhile, political cooperation centred on security anddefence-related issues, including defence planning, con-ceptual approaches to arms control, civil-military relations,air-traff ic management and the conversion of defenceindustries, as well as NATO’s so-called “Third Dimension”,

that is the Alliance’s scientific and environmental pro-grammes.

The NACC broke new ground in many ways. However, itfocused on multilateral, political dialogue and lacked thepossibility of each Partner developing individual coopera-tive relations with NATO. The Partnership for Peace,launched in January 1994, was designed to meet this need,offering tailored programmes of cooperation with NATOand a strengthened political relationship. This included theright of any Partner to consult with the Alliance, if it per-ceived a threat to its political independence, security or ter-ritorial integrity. The focus of the Partnership was on thedevelopment of forces that would be interoperable withthose of the Alliance – primarily military forces – andissues such as civil-emergency planning. The Partnershipfor Peace allowed Partners to develop their own bilateralrelationship with NATO at their own pace.

As the political relationship between Allies and Partnersdeepened, the Partnership for Peace also provided themechanisms by which Partners could take part in NATO-led operations if they wished to do so. In practice, this hasmeant participation in NATO actions in the Balkans,where, even before deployment of the first peacekeepingmission, Partners have played a critical role.

During the Bosnian War, several Partner countries helpedthe Alliance enforce an arms embargo against the whole ofthe former Yugoslavia, economic sanctions against Serbiaand Montenegro and a flight ban over Bosnia. Albania, forexample, allowed NATO ships to use its territorial waters toenforce the arms embargo and economic sanctions, andHungary, then a Partner, allowed NATO Airborne EarlyWarning Aircraft to use Hungarian airspace to monitor theBosnian no-fly zone. Moreover, troops from 14 Partnercountries served alongside their Alliance counterparts inthe Implementation Force (IFOR), the f irst NATO-ledpeacekeeping operation, bringing in extra force capabilitiesand added legitimacy for the mission.

As Partners placed their soldiers in the field and theirforces operated under NATO command in a high-risk envi-ronment, they naturally sought greater opportunities to takepart in the decision-making process, which determined theobjectives and operating procedures of the mission. In thebuild-up to IFOR, this had largely been carried out on anad hoc basis, as the mission was a first for the Alliance.With Partners willing to show such commitment to helpingsolve security problems beyond their own borders, a newapproach to partnership was needed.

In the wake of a visionary speech by then US Secretaryof State Warren Christopher in September 1996, whichproposed the creation of a new security forum, NATOundertook a major examination of its partnership strategy.One of the prime aims of this process was to ensure greaterdecision-making opportunities for Partners across the

NATO’S EVOLVING PARTNERSHIPS

Autumn 2001 NATO review 7

entire scope of the Partnership. The other was to seize theopportunity to focus the Partnership ever more closely onoperational issues. The outcome was the creation of theEAPC and an Enhanced and More OperationalPartnership.

On the political-consultation front, it now made sense tomove beyond the NACC and to build a security forum tomatch the increasing sophistication of the relationshipsbeing established through the Partnership for Peace. Ratherthan define its membership by who used to be NATO’sadversaries, a new cooperative body needed to encompassall Euro-Atlantic countries wishing to build a relationshipwith NATO. This new body could include traditionally neu-tral countries, which had proved to be valuable members ofthe Partnership for Peace, such as Austria, Finland andSweden, who were not full members of the NACC.

In moving beyond the NACC, the EAPC represented acommitment on the part of NATO to involve Partners evermore closely in Alliance decision-making processes. Itwould also provide a framework for involving Partnersmore closely in consultations for the planning, executionand political oversight of what are now known as NATO-led PfP Operations. As the multilateral body pulling thethreads of the Partnership together, the EAPC retained theNACC’s focus on practical political and security-relatedconsultations. But it expanded the scope of these consulta-tions to include crisis management, regional issues, arms-control issues, the proliferation of weapons of massdestruction and international terrorism, as well as defenceissues, such as defence planning and budgets, includingdefence policy and strategy. Civil-emergency and disasterpreparedness, armaments cooperation and defence-relatedenvironmental operations made up an impressive list.

In addition to traditional consultations, the EAPC hascarved out a role for itself in helping address major issuesof concern to both NATO members and Partners. It hasachieved this by making the most of the flexibility provid-ed by a minimum of institutional rules to adopt innovativeapproaches to security issues. Use has, for example, beenmade of open-ended working groups, enabling those coun-tries most concerned to take initiatives and prepare workfor the full forum. Consultations on the Caucasus andsoutheastern Europe have, for example, benefited from thisapproach. The EAPC has also encouraged its members tolook at issues from new angles, rather than seeking toresolve long-standing sticking points, an approach that hasproved fruitful where other organisations have the recog-nised lead responsibility.

As for the Enhanced and More Operational Partnership,its new direction built upon experience gained during theearly years of the Partnership for Peace, and on lessonslearned in the NATO-led peacekeeping operations inBosnia. Among steps taken to reinforce and improve thePartnership to make it more operational, three initiatives

NATO’S EVOLVING PARTNERSHIPS

NATO review8 Autumn 2001

stand out. These are the Planning and Review Process(PARP); the Operational Capabilities Concept (OCC); andthe Political-Military Framework for NATO-led PfPOperations.

The PARP lays out interoperability and capabilityrequirements for participants to attain and includes anextensive review process to measure progress. By provid-ing the standards to aim for, it helps Partners develop thecapabilities that will form the backbone of the more opera-tional aspects of Partnership. Over the years, the require-ments have become more complex, demanding and linkedto the capability improvements that Allies have set them-selves in the Defence Capabilities Initiative. Indeed,increasingly, the PARP has come to resemble the Alliance’sown defence-planning process, with ministerial guidancefor defence-planning objectives; Partnership Goals similarto NATO Force Goals; and the PARP Assessment mirroringNATO’s Annual Defence Review.

When considering an actual operation and the use ofthese Partner forces, NATO commanders need to knowwhat forces are available and how capable they are. TheOCC was developed to address these critical issues andaims to provide NATO commanders with reliable informa-tion about potential Partner contributions to allow for therapid deployment of a tailored force. This complements theassessment made under the PARP and should help improvethe military effectiveness of those forces assessed. ForNATO commanders, more militarily effective Partner con-tributions improve the Alliance’s capability to sustain long-term operations.

Putting into place mechanisms to help increase Partnercontributions is, of course, only part of the story. In the firstinstance, Partners have to decide whether they want theirforces to be involved in a particular operation. This is thecritical interface between the practical and the political –brought together by the EAPC.

Through the EAPC, all Partners are involved in consul-tations on developing crises, which might require thedeployment of troops. In order to encourage Partners tocommit forces to complicated and potentially dangerousoperations, NATO has developed a mechanism to ensurethat consultations are no longer conducted on an ad hocbasis, but are institutionalised according to procedures thatrecognise the importance of Partner contributions. This ini-tiative, the third major element of the Enhanced and MoreOperational Partnership, is known as the Political-MilitaryFramework for NATO-led PfP Operations.

When an escalating crisis is under discussion, all EAPCmembers are involved. If NATO believes that troops mayneed to be deployed, the North Atlantic Council, NATO’shighest decision-making body, can recognise Partners whodeclare an intention to contribute to the force. ThesePartners are then able to exchange views with Allies and

associate themselves with the first stage of planning for anoperation. They will also be consulted on the plan for theoperation and be involved in the force-generation process,when the commander draws up the composition of theforce. It is at this stage that the OCC should save time andeffort through the increased predictability about the capa-bility of Partner forces that are available.

Once Partner contributions are accepted, discussions onthe operation can take place between NATO and those con-tributing Partners. Meanwhile, the full EAPC is stillinvolved in general discussions on the particular operationand the political circumstances surrounding it. Whiletroop-contributing Partners are consulted to the maximumdegree possible, final decisions still need to be taken by theAlliance, upon whose assets such operations depend. Thisconsultation process continues for the duration of an oper-

ation, ensuring that Partner voices are heard when impor-tant decisions are taken.

The contribution of Partners to the peacekeeping opera-tions cannot be overestimated. Indeed, it could be arguedthat NATO’s involvement in bringing peace to Kosovowould not have been possible without Partner participation.Not only have Partners provided valuable political support,but also mission-essential assets for NATO’s use, includingthe use of airspace during the air campaign and vital logis-tics bases to sustain lines of communication for KFOR. Asthe relationship between Allies and Partners grows, it isincreasingly possible to speak of a shared community ofvalues underlying these practical undertakings. In the tenyears since the inception of the NACC, Partnership hasevolved to become a fundamental feature of Euro-Atlanticsecurity. ■

NATO’S EVOLVING PARTNERSHIPS

Autumn 2001 NATO review 9

Mediterranean DialogueNATO launched its Mediterranean Dialogue in 1994

in recognition of the fact that European security andstability is closely linked to that in the Mediterranean,writes Alberto Bin.

This programme, which includes Algeria, Egypt,Israel, Jordan, Mauritania, Morocco and Tunisia, aimsto contribute to regional security and stability, toimprove mutual understanding, and to correct misper-ceptions about NATO among Mediterranean countries.

The Dialogue is based primarily on bilateral relationsbetween each participating country and the Alliance.However, it also allows for multilateral meetings on acase-by-case basis. It offers all Dialogue countries thesame basis for discussion and joint activities and com-plements other related but distinct international initia-tives, such as those undertaken by the European Unionand the Organisation for Security and Cooperation inEurope.

The Dialogue provides for political dialogue andpractical cooperation with participating countries. Thepolitical dialogue consists of regular bilateral politicaldiscussions, as well as multilateral conferences atambassadorial level. These provide an opportunity toexchange views on a range of issues relevant to security

Alberto Bin works on the Mediterranean Dialogue inNATO’s Political Affairs Division.

in the Mediterranean, as well as on the future develop-ment of the Dialogue.

Practical cooperation is organised through an annualWork Programme and takes various forms, includinginvitations to officials from Dialogue countries to par-ticipate in courses at NATO schools. Other activitiesinclude seminars designed specifically for Dialoguecountries, particularly in the field of civil-emergencyplanning, as well as visits of opinion leaders, academ-ics, journalists, and parliamentarians from Dialoguecountries to NATO.

The Alliance awards institutional fellowships toscholars from the region. In addition, the Dialogue pro-motes scientif ic cooperation through the NATOScience Programme. In 2000, for instance, 108Dialogue-country scientists participated in NATO-sponsored scientific activities.

The Work Programme also has a military dimensionthat includes invitations to Dialogue countries toobserve exercises, attend seminars and workshops, andvisit NATO military bodies. In 2000, 104 military offi-cers from the seven Dialogue countries participated insuch activities. In addition, NATO’s Standing NavalForces in the Mediterranean visit ports in Dialoguecountries. Otherwise, three Dialogue countries – Egypt,Jordan and Morocco – have contributed peacekeepersto NATO-led operations in Bosnia and Herzegovina.And Jordan and Morocco currently have soldiers in theKosovo Force.

NATO review10 Autumn 2001

“an institutional relationship of consultation and coopera-tion on political and security issues” – those states that hademerged from the wreckage of the Warsaw Pact and theSoviet Union. Later in the decade, however, the NACCseemed a bit of an anachronism: defined more by what itsnon-Allied members had been than about aspirations forthe future. And the NACC did not formally include most ofthe states that emerged from the break-up of Yugoslavia orEurope’s neutral and non-aligned countries.

It made sense to recast the NACC to make a fresh startand enable countries that were neither “ex-communist” nor“ex-Warsaw Pact” to become full members. The initiativecame in a speech by then US Secretary of State WarrenChristopher at Stuttgart, Germany, on 6 September 1996.This date marked the 50th anniversary of an historicaddress by one of his predecessors, James Byrnes, whichwas called the “speech of hope” because of its vision forpost-war Europe and US engagement. SecretaryChristopher chose to speak of a New Atlantic Communityand wanted a headline-grabbing idea, which the State

Robert E. Hunter is a senior adviser at the RANDCorporation and was US ambassador to NATO between1993 and 1998.

W hen created in May 1997, the Euro-AtlanticPartnership Council (EAPC) was NATO’s poorstepchild. It lacked, then and now, the decision-

making power of the North Atlantic Council, which is lim-ited to the 19 NATO Allies. Initially, it had no role in man-aging the practical work of the Partnership for Peace, withwhich it shares almost the same membership. Even itssemi-annual ministerial meetings and occasional summitshave tended to be long on speeches and short on substance.But this Cinderella of an institution has the potential tocontribute to Euro-Atlantic security in a way that no othercan match.

The EAPC was born almost by accident. It was precededby the North Atlantic Cooperation Council (NACC), creat-ed in 1991 to bring within the broader NATO family – in

Getting Cinderella to the ballRobert E. Hunter examines the potential of the Euro-Atlantic PartnershipCouncil and proposes that it play a greater role in Euro-Atlantic security.

© N

ATO

Ministerial meeting: the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council has the potential to contribute to Euro-Atlantic security in a way that no other institution can match

Department hastily provided: namely, to convert the NACCinto something new and to call it the Atlantic PartnershipCouncil. Details were left for later.

As the new institution began to take shape, the prefix“Euro-” was added to the proposed name. Both existingNACC members and other European countries thatbelonged to the Partnership for Peace were invited to join.And views were canvassed within the Alliance about whatthe new EAPC should be and do. The results were agreed atthe EAPC’s formal founding – the NACC’s final meeting –at Sintra, Portugal, on 30 May 1997. The EAPC wouldfocus on issues like crisis management, arms control, inter-national terrorism, defence planning, civil-emergency anddisaster preparedness, armaments cooperation and peace-support operations. And NATO pledged that the EAPCwould “provide the framework to afford Partner countries,to the maximum extent possible, increased decision-mak-ing opportunities relating to activities in which they partic-ipate”. Unclear, then and now, is the meaning of “to themaximum extent possible”.

These were ambitious goals and the newly createdEAPC agreed to institutionalise a wide range of meetingsto see them implemented. These included monthly meet-ings of ambassadors; twice-yearly meetings of foreign anddefence ministers; occasional meetings of heads of stateand government; as well as so-called “16 (now 19)-plus-one” meetings of the Allies and individual Partners. Sincethen, the EAPC has sought to make its mark in a variety ofareas, ranging from identifying ways in which it might con-tribute to the challenge of small arms and light weapons toorganising exercises in civil-emergency planning with theEuro-Atlantic Disaster Response Coordination Centre.

The EAPC could, of course, do much more. However, itstill lacks decision-making authority. This power is jealous-ly guarded by the North Atlantic Council, in large measurebecause the Allies have special obligations and responsibil-ities under the Washington Treaty, NATO’s founding char-ter, and bear the brunt of organising and funding EAPCactivities. Yet, in 1999, the Allies began to engage EAPCmembers in helping to shape the way in which Partnercountries would take part in so-called “non-Article 5 oper-ations”, that is operations not related to collective defence.The aim was to engage Partner countries, within limits, inpolitical consultations and decision-making, in operationalplanning and in command arrangements for future NATO-led operations in which they participate.

Because of the growing importance of the Partnershipfor Peace, this was a natural step. Further developmentsincluded issues affecting Partner countries under NATO’sDefence Capabilities Initiative and the creation of anExpanded and Adapted Planning and Review Process – inpart to improve the interoperability of forces and capabili-ties – and consultations on crises and other political andsecurity-related issues. The EAPC’s Action Plan for 2000-

2002 also covers consultations and cooperation on regionalmatters, including Southeastern Europe and the Caucasus,as well as issues relating to the Stability Pact, the EU-ledinitiative to develop a comprehensive, international frame-work to help build long-term stability in southeasternEurope.

Despite these efforts, the EAPC has yet to reach itspotential. There are two reasons for helping it do so. First,however many countries are invited to join the Alliance atnext year’s Prague Summit, some aspirants will be left out.It is critical that the EAPC give these countries a firm sensethat they belong within the broader NATO family. Second,some EAPC countries, notably in the Caucasus and CentralAsia, are unlikely ever to join NATO. Nevertheless, theEAPC could help them, as well, gain in security and confi-dence.

Giving the EAPC true decision-making powers, beyondthe capacity to help shape decisions of the North AtlanticCouncil, is not currently on the Alliance agenda. However,as Partners demonstrate their capacity to take on additionalresponsibilities, this should be reviewed. Certainly, furtherintegration of the activities of Partners with Allies shouldbe the next immediate goal. Several possibilities stand out:

Crisis management: At present, most crisis consulta-tions at NATO centre on the North Atlantic Council. Evenhere the Alliance is handicapped because it lacks the com-petence of a sovereign government. NATO’s role in helpingto manage crises – like that in the former Yugoslav Republicof Macedonia* – is largely limited to specific tasks thatmember states assign to the Secretary General. In Bosniaand Herzegovina (Bosnia) and Kosovo, for instance, NATOfound itself called upon to act militarily, without havingbeen directly engaged in the preceding diplomacy. TheEAPC cannot be expected to develop a competence thateven the North Atlantic Council does not have, but it isstriking that EAPC members include countries with a gooddeal of experience in, as well as proximity to, areas mostchallenging to NATO, especially in the Balkans. The EAPCshould therefore be developed into a primary forum fordevising viable crisis outcomes, not just a place to brief onthe results of North Atlantic Council deliberations.

The Balkans: The EAPC is already active in Southeast-ern Europe, and in particular much of the formerYugoslavia, which is a special challenge for the interna-tional community. At the Alliance’s 1999 WashingtonSummit, NATO launched its South East Europe Initiative,one pillar of which is an Ad hoc Working Group, under theauspices of the EAPC, which promotes regional coopera-tion. At an EAPC ambassadorial meeting in July 2000,Bulgaria announced the establishment of the South EastEurope Security Cooperation Steering Group (SEE-GROUP), a forum in which all countries of the region areable to meet to exchange information and views on projectsand initiatives designed to stimulate and support practical

NATO’S EVOLVING PARTNERSHIPS

Autumn 2001 NATO review 11

cooperation between members. Since the change of gov-ernment in Zagreb in early 2000, Croatia began to buildbridges with the Alliance. As a first step, the country joinedboth the EAPC and the Partnership for Peace in May of thatyear and is now an active participant in SEEGROUP. As thenew, democratic government in Belgrade opens up toNATO, the EAPC should play a leading role in assisting theFederal Republic of Yugoslavia’s transition and reintegra-tion into the international community.

“Out-of-Area” dispute and conflict management:Many other areas of concern to NATO members eitherinclude or border EAPC member states. So far, the EAPChas had little experience in trying to mediate, ameliorate orresolve tensions and conflict between its members in theCaucasus and Central Asia. But the Alliance – and specifi-cally the EAPC – should not shy away from this possibili-ty, nor accept that, of necessity, ad hoc arrangements orsome other body (like the Organisation for Security andCooperation in Europe) should take precedence.Leadership will be important. So, too,will be the development of a senseamong its members that the EAPC canadd value as a basic European securityinstitution, born of NATO, to whichregional disputes and crises can properlyand productively be brought. This willonly emerge through experience, afterthe EAPC selects one or more such situ-ations and sets a positive precedent forits potential role.

Engaging Russia: In some cases, thedevelopment of such a dispute and con-flict-management role for the EAPC,among its own members, will be more possible and pro-ductive – for example, as a support to or even replacementfor the Minsk Group on Nagorno-Karabakh, a region con-tested between Armenia and Azerbaijan – if Russia can beconvinced to play a greater role. In the run-up to thePrague Summit, with the prospect of invitations to joinNATO being extended to Central European states, theAlliance will, in any case, have to reach out to Moscow todemonstrate that NATO is neither challenging Russia,strategically or politically, nor seeking to isolate it. Russiahas so far chosen to play a relatively passive role in theEAPC and the Partnership for Peace, and it has been reluc-tant to test the limits of the Permanent Joint Council, theforum for NATO-Russia consultation and cooperation.NATO already has an interest in convincing Russia that ithas a valid place within a broader concept of Europeansecurity and that its basic interests in Europe are compati-ble with NATO’s. Indeed, if Russian President VladimirPutin’s musings about Russia’s one-day joining NATO canbe nurtured, not so much for the specific idea but for widerpossibilities, then the EAPC could become a useful vehi-cle for Moscow to work with NATO. This could supple-ment the Permanent Joint Council, while providing

NATO’S EVOLVING PARTNERSHIPS

NATO review12 Autumn 2001

Moscow with more legitimacy than it now has for engag-ing other EAPC countries, without generating fears thatMoscow would gain undue influence over their strategicand political choices. The EAPC could therefore become amechanism for helping to reconcile Russia to NATO’sexpansion to include as members countries close to itsborders.

EAPC, ESDP and EU-NATO Relations: NATO hasbeen building a relationship with the European Union asthat institution develops a European Security and DefencePolicy (ESDP). This process is far from complete and, inmy view, far from harmonious. One way of trying to recon-cile differences is via the alignment of their respective bod-ies, especially through joint meetings of the North AtlanticCouncil and the European Union’s new Political andSecurity Committee (PSC) at ambassadorial and ministeri-al levels. Given that both the European Union and NATOare taking in new members from Central Europe and areotherwise deeply involved there, that both are engaged in

the Balkans, that both have developedspecial relationships with Russia andUkraine, and that both have interests inthe Caucasus and Central Asia, thesejoint meetings should be extended toinclude parallel EAPC-PSC consulta-tions. This could also stimulate theEuropean Union’s companion CommonForeign and Security Policy to be moreoutward-looking. In any event, theEuropean Union and NATO do share abroad agenda, even if they approachmost non-defence issues from differentperspectives. In the effort to eliminatethe artif icial barriers that have for so

long existed between these two institutions, the EAPCcould prove a useful instrument.

Finally, it is important to remember that, as NATO con-tinues to take in new members, both the EAPC and thePartnership for Peace will naturally change in character,and in some regards in purpose. With further NATOenlargement, the relative balance between Partners andAllies in the EAPC will progressively shift towards the lat-ter. The non-Allied membership of the EAPC will increas-ingly be dominated by countries east of Turkey. This is astrong argument for the EAPC to emphasise dispute andconflict resolution, as well as coordination with theEuropean Union and other institutions, to help countries ofthe Caucasus and Central Asia develop their politics andeconomies, as well as reform their militaries.

Looking to the future, the vision of a “Europe whole andfree” can only be realised if “security” is understood in thebroadest sense. The EAPC has much to offer towards thatgoal and could develop into an effective political and secu-rity instrument with a remit that goes far beyond its origi-nal purposes. ■

As NATO continues totake in new members,both the EAPC andthe Partnership forPeace will naturallychange in character andpurpose

Autumn 2001 NATO review 13

ety of documents and policies, each of which applies to aspecific area or issue – but which, when taken together,form an intellectually coherent whole. The Alliance worksto promote regional security cooperation primarily in theBalkans, the Caucasus and the Baltics, as part of NATO’soverall efforts to promote peace and security across theEuro-Atlantic area. NATO takes an individual, targetedapproach to each region, because each faces its own securi-ty challenges in a unique geopolitical context, and becauseeach is of unique security interest to the Alliance.

The Balkans

Southeastern Europe is of enormous geopolitical impor-tance to NATO. Kosovo, for example, sits in a vital strate-gic area for the Alliance: just above two NATO members,below new NATO members in Central Europe, and organi-cally linked to Bosnia and Herzegovina (Bosnia).Instability, conflict and widespread human rights abuses inthis region have posed direct challenges to NATO’s inter-ests over the past decade and the Alliance has been obligedto work to ensure that crises do not destabilise neighbour-ing countries.The highest-profile tools through whichNATO has promoted peace and security in the Balkans arethe NATO-led peacekeeping operations in Bosnia andKosovo. But the Alliance has also engaged in a number ofother military and political efforts to promote stabilityacross southeastern Europe, from preventive diplomacy tothe active promotion of regional cooperation.

Perhaps the most prominent example of such efforts isNATO’s South East Europe Initiative. Launched at theAlliance’s 1999 Washington Summit to promote regionalcooperation and long-term security and stability in theregion, it built on already extensive cooperative relation-

James Appathurai is senior planning officer in the policyplanning section of NATO’s Political Affairs Division.

In the field of Euro-Atlantic security cooperation, cer-tain big-ticket arrangements get almost all the press:NATO and its Partnership for Peace, the European

Union’s developing defence dimension, and theOrganisation for Security and Cooperation (OSCE). Butalongside these large and well-established structures,smaller fledgling regional arrangements are making impor-tant contributions to building security in sensitive areasthroughout the Euro-Atlantic area. These lower-levelefforts at cooperation are an important pillar in the overallsecurity architecture and the Alliance is eager to assist theirdevelopment.

The logic of regional security cooperation is clear. Bypooling resources in the right way, like-minded countriescan enhance their own security more effectively.Economically, cooperation allows for economies of scaleand the acquisition of equipment that would otherwise beunaffordable for individual, especially smaller countries.Militarily, cooperation multiplies the potential of any indi-vidual country’s armed forces. Politically, cooperation inthe security field is the ultimate confidence and security-building measure because it requires transparency, coordi-nation and mutual trust.

NATO stands as vivid testimony to the success of thisapproach. What began, in 1949, as a group of nations divided by very recent history – and, not least, by an ocean– has become the most cohesive and effective political/mil-itary Alliance ever. And the NATO experience demon-strates that regional cooperation is not a substitute for otherendeavours, but a complement to them. Any country canhave multiple security affiliations, without any individualaffiliation suffering as a result. Hence, for example, theNorth American Aerospace Defence cooperation betweenCanada and the United States, or the European Union’ssecurity and defence identity.

It is precisely because the potential of regional and sub-regional cooperation is so clear that the Alliance has lentincreasing support to these efforts, even among countriesthat do not aspire to NATO membership. No single,approved document sets out the rationale behind regionalcooperation and the modalities by which the Alliance willsupport it. Instead, that approach is set out through a vari-

Promoting regional security James Appathurai examines how NATO promotes regional security cooperation

in the Balkans, the Caucasus and the Baltics.

BOSNIAAND

HERZEGOVINA

HUNGARYSLOVENIA

CROATIA

Serbia

Adriatic SeaITALY

ROMANIA

BULGARIA

THE FORMERYUGOSLAV REPUBLIC

OF MACEDONIA*

ALBANIA

Montenegro

Kosovo

Vojvodina

GREECE

ships with Partners through the Euro-Atlantic PartnershipCouncil (EAPC) and the Partnership for Peace. It alsoextended to include countries that did not belong to theseinstitutions and programmes, Bosnia and (at the time)Croatia, and foresaw the extension to the Federal Republicof Yugoslavia. An Ad hoc Working Group on RegionalCooperation, set up under EAPC auspices, promotesregional cooperation to stimulate and support practicalcooperation among countries of Southeastern Europe. Thecountries of the region, for example, established the SouthEast Europe Security Cooperation Steering Group (SEE-GROUP) in September 2000, the chair of which rotatesamong members, to support the various cooperativeprocesses now at work. Activities include demining, effortsto control small arms and light weapons, crisis-manage-ment simulation and air-traffic management.

Together with other international organisations, theAlliance is working to build regional stability in the frame-work of the EU-sponsored Stability Pact for South EasternEurope. In this way, NATO has helped set up programmesto assist discharged officers make the transition from mili-tary to civilian life (see article on page 23) and others toclose military bases and convert them to civilian uses.Other activities require regional leadership. A good exam-ple is the South East Europe Common Assessment Paperon Regional Security Challenges and Opportunities(SEECAP). This was a NATO idea, taken forward by coun-tries of the region, including the Federal Republic ofYugoslavia. The SEECAP sets out common perceptions ofsecurity challenges among signatory nations and should bea vital f irst step in building peaceful relations in theBalkans. It also sets out opportunities for participatingcountries to cooperate in addressing these challenges.

The CaucasusThe scenario is different in the Caucasus, where NATO

is also promoting regional cooperation. Although there areequally intractable problems in this region, the onlyAlliance member directly to feel the effects is Turkey.Moreover, there is certainly a perception that NATO as anorganisation has limited influence in the region and thatNATO members can more usefully contribute to peace andsecurity there through bilateral measures, or by workingthrough other organisations such as the OSCE or theUnited Nations.

For all these reasons, NATO takes a more low-keyapproach in the Caucasus. Even at this lower level, however, the Alliance still actively supports security coop-eration in the region as a way to promote transparency andconfidence-building. The central vehicle for these NATOefforts is the EAPC Ad hoc Working Group on Prospectsfor Regional Cooperation in the Caucasus. Priority areasidentified by the Working Group for practical regionalcooperation are defence-economics issues, civil-emer-gency planning, science and environmental cooperation,and information activities.

NATO’S EVOLVING PARTNERSHIPS

NATO review14 Autumn 2001

Under the auspices of the EAPC, a regional cooperationseminar on energy security in the Caucasus took place inAzerbaijan in 2000, which covered the environmental, eco-nomic and civil-emergency aspects of energy security.Seminars have also been held elsewhere in the regionon defence economics, civil-emergency planning, civil-military cooperation, small arms and light weapons, andscientific cooperation. The possibility of further confer-ences is now being discussed on international terrorismand non-proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, aswell as on crisis management and mine action. These areall valuable endeavours because the focus is on issues ofimmediate security interest to the countries of the region.

It must be stressed that when it comes to promotingcooperation in the Caucasus, other regional groupings,such as the OSCE and the GUUAM, an organisation

including Georgia, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan andMoldova, take the lead. But NATO continues to play a role,encouraging the development of common solutions amongcountries facing common challenges.

The BalticsThe third major region in which NATO takes an active

interest in promoting cooperation is the area of the BalticSea. Unlike the Balkans, where the challenges are severeand NATO’s interest immediate, or the Caucasus, where thechallenges are equally intractable but affect the entireAlliance less directly, the Baltics are a region of directgeopolitical importance to the Alliance, but one in whichregional cooperation is already progressing nicely and doesnot require the same level of support from NATO.

This indigenous success should come as no surprise, asthis is an area in which regional cooperation has a long history. Certainly, once Estonia, Latvia and Lithuaniabecame states in the beginning of the 20th century, theynaturally looked to closer forms of cooperation, for clear

Caspian Sea

RUSSIA

BlackSea

GEORGIA

AZERBAIJAN

ARMENIA

TURKEY

IRAN

AZERBAIJAN

geographic, political, economic and military reasons.Today, that cooperation is stronger still – and the reasonsare obvious. From a geographical standpoint, these threecountries still form a natural region. They are all smallstates, with small populations and small economies.Furthermore, their socio-economic evolution since the1920s has been similar and, at present, they have no realdisagreements among themselves.

Perhaps as a result, it is safe to say that nowhere inEurope has subregional cooperation been as profound inthe post-Cold War era as in the Baltic Sea area. TheCouncil of Baltic Sea States (CBSS), which was initiated in1992 by the then Danish and German foreign ministers, isan excellent example of a successful regional grouping,bringing together 12 countries to deepen cooperation on avariety of issues. While traditional security was not initially

on the agenda, the CBSS now promotes subregional coop-eration against organised crime and search and rescue atsea, even including the use of military units.

The CBSS has served as an example for similar endeav-ours in other parts of Europe, in particular the Balkans.Furthermore, the cooperative activities at the state level areunderpinned by a well-developed network of specialisedorganisations, as well as a web of cooperation betweenprovinces, cities and municipalities across the Baltics. Thisis especially the case in the security sector, where all threestates share a desire to consolidate their independence andrebuff any instability from the East. Regular trilateral coop-eration on protection of airspace, for example, has led tothe recent establishment of the regional airspace surveil-lance system (BALTNET) for all three countries.

The three countries also realise that with their limiteddefence resources, it makes sense to work on their develop-ment together. The Baltic Security Assistance Group is aneffective body for international coordination of security assis-

tance to the defence forces of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania.The Baltic Defence College, a military academy primarilyfor officers from the Baltics that operates in English, is alsoa good example of cooperation in defence education.

The three Baltic countries also want to demonstrate thatthey are good European partners, willing to contribute tosecurity. The joint peacekeeping battalion, BALTBAT, andthe Baltic squadron (BALTRON) are obvious examples ofconcrete cooperation in action. The BALTBAT has alreadybeen active in the NATO-led peacekeeping operations inthe Balkans.

NATO’s support for Baltic participation in its peace-keeping operations is one way in which the Alliance and itsmembers are encouraging cooperation among the threeBaltic countries. These operations have demonstrated that,by working together, the Baltics can punch above theirweight and have an influence on Euro-Atlantic events dis-proportionate to their individual size.

NATO is also facilitating such cooperation through theMembership Action Plan and the Partnership for Peace.Both projects aim to improve the military capabilities ofparticipating countries and both focus, in particular, onimproving interoperability for combined operations. Theseare essential standards for increased regional cooperation,which the three Baltic countries are working to meet.

Alliance members are also supporting Baltic regionalcooperation on a national basis. Denmark, for example, hasplayed a leading role, providing assistance to the BalticDefence College and accommodating Baltic peacekeepersin Danish formations in the Balkans. The United States hasalso provided crucial political support. This has manifesteditself, in particular, through the 1998 US Baltic Charter, anagreement that, according to then US President BillClinton, is designed to encourage close cooperation amongthe Baltic states and their neighbours and to demonstrate“America’s commitment to help Estonia, Latvia andLithuania to deepen their integration, and prepare for mem-bership in the European Union and NATO.”

President Clinton’s linking of regional cooperation andmembership in Euro-Atlantic institutions is importantbecause it is in the Baltic region, in particular, that con-cerns are sometimes raised about how successful regionalcooperation might undermine aspirations to join NATO.Far from being a constraint against Alliance membership,successful regional cooperation is a powerful selling pointfor aspiring members. NATO is an organisation withinwhich member states work together, pool resources anddevelop policy through consensus. Successful regionalcooperation not only prepares aspirants for membership, italso demonstrates to existing members that these countriesare willing and able to accept the conditions and workingmethods of the Alliance – while of course building securi-ty for all participants. ■

NATO’S EVOLVING PARTNERSHIPS

Autumn 2001 NATO review 15

Norwegian Sea

NORWAY

BalticSea

SWEDEN

DENMARKLITHUANIA

LATVIA

ESTONIA

POLAND

FINLAND

GERMANY

NorthSea

Kaliningrad

RUSSIA

BELARUS

NATO review16 Autumn 2001

increased its involvement in the Partnership for Peace, bothin quantitative and qualitative terms, and now participates inmore than 100 activities every year.

This summer, Georgia achieved a milestone when it host-ed the first, full-scale Partnership for Peace exercise in theSouthern Caucasus, Cooperative Partner 2001. The exercise,which took place in and around the Black Sea port of Potiand included some 4,000 servicemen from nine NATO andsix Partner countries, aimed to develop combined naval andamphibious interoperability between Alliance and Partnerparticipants in peace-support operations and the provision ofhumanitarian assistance. This was the largest-scale activityin which Georgia has been involved with NATO. It hashelped promote military-to-military cooperation betweenthe Georgian armed forces and those of Alliance members.And it reflects an ever-deepening relationship betweenGeorgia and NATO.

Georgia has also consistently supported NATO’s efforts toend the violence and build stability in the Balkans. Indeed,we have sent an infantry platoon to the NATO-led KosovoForce (KFOR) to demonstrate our commitment to the peaceprocess in that part of Europe. Moreover, we firmly believethat, since no country can insulate itself from instabilityelsewhere, threats to security in one part of the Euro-Atlantic area are threats to the entire Euro-Atlantic area. Inorder to build genuine security in Europe, therefore, everycountry should contribute, according to its own means, toeradicating all hotbeds of instability. Georgia has thereforeconsistently been eager to participate in activities designedto improve security throughout the Euro-Atlantic area andaspires eventually to integration in NATO.

Both Georgia and the wider Caucasus have great poten-tial. Georgia is, for example, at the centre of efforts to buildthe Eurasian Transport Corridor – a key east-west tradeartery between Asia and Europe. It is also a natural transporthub for this revitalised “Silk Road” which has three maincomponents: the Transport Corridor Europe-Caucasus-Asia,a Trans-Caucasian Strategic Energy Corridor (to transportCaspian energy resources to Western markets) and a Trans-Caucasian Telecommunications Network. However, forthese projects – which are being assisted by the EuropeanUnion and other interested countries – to see fruition, it willbe necessary to stabilise the entire region and create tangibleguarantees for peace and sustainable development.

Irakli Menagarishvili is foreign minister of Georgia.

Georgia’s overriding foreign policy aim is to integrateitself into Euro-Atlantic political, economic andsecurity structures to join the European community

of nations and fulfill an historical aspiration of the Georgianpeople. Ever since the disintegration of the Soviet Union, mycountry has attempted to build a modern, democratic socie-ty and forge closer and deeper relations with countries andinstitutions throughout the Euro-Atlantic area. At the sametime, Georgia and the wider Caucasus have experiencedmuch instability and turbulence. Developing a long-termand mutually beneficial relationship with the Alliance hastherefore been a national priority for the past decade, onewhich is evolving to the benefit of both Georgia and NATO.

As NATO opened its arms to former members of theWarsaw Pact and successor states of the Soviet Union in theearly 1990s, Georgia was quick to join all new security insti-tutions and programmes. It became a member of the NorthAtlantic Cooperation Council in 1992; signed thePartnership for Peace Framework Document in 1994; andbecame a founding member of the Euro-Atlantic PartnershipCouncil (EAPC) in 1997. Georgia has progressively

Partnership in practice:Georgia’s experience

Irakli Menagarishvili describes Georgia’s relationship with the Alliance and howit is evolving to the benefit of both Georgia and NATO.

Georgia’s position towards the wider Caucasus is basedon principles presented by President Eduard Shevardnadzein his Initiative on a Peaceful Caucasus of 1996 and joint-ly signed by the presidents of Armenia and Azerbaijan.This initiative, which excludes the use of force in resolv-ing disputes, proposes a political formula that aims attransforming the existing confrontation and crises in theregion into cooperation and general welfare.Implementation of these principles will only be possiblewith the concerted efforts of countries of the region,neighbours and other leading actors on the world stageinterested in a peaceful and stable Caucasus. In this con-text, other initiatives – including the proposed StabilityPact for the Caucasus – deserve serious consideration.

In addition to cultivating closer relations with NATO,Georgia has sought to build bridges with and join otherinternational organisations. It is a member of the Councilof Europe, the Organisation for Security and Cooperationin Europe (OSCE) and the World Trade Organisation, andit signed a Partnership and Cooperation Agreement withthe European Union in 1996. Georgia is also a member ofthe Black Sea Economic Cooperation organisation, whichseeks to promote mutual understanding, an improved polit-ical climate, and economic development in the Black Seaarea. And it is part of the GUUAM – Georgia, Ukraine,Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan and Moldova – a regional organi-sation aiming to build common approaches to political,economic, humanitarian and ecological problems.

The most pressing security issues within Georgia arethe internal disputes with separatists in Abkhazia andTskhinvali (formerly known as South Ossetia).Satisfactory resolution of these disputes is an essentialprecondition for the establishment of stable political,social and economic conditions, and for the return of some300,000 Georgians who were forced to flee ethnic vio-lence in the early 1990s. We aim to consolidate our inde-pendence by making it clear to our neighbours that anindependent, prosperous, stable and unified Georgia is intheir best interests. This applies especially to the RussianFederation, which currently has some 6,000 troops sta-tioned on Georgian soil. Georgia seeks the phased with-drawal of all Russian troops from Georgian territory andthe closure of their military bases. At the OSCE’s IstanbulSummit in 1999, Russia signed an agreement to this effect,including a withdrawal timetable for two of the four bases,only one of which was fully met.

Georgia views the EAPC as a particularly importantinstitution, capable of reviewing and helping solve numer-ous security problems in the Euro-Atlantic area. SincePartners are able to propose the topics of discussions andconsultations in the EAPC, Georgia has used this forum totable a series of issues of special concern. These includeissues related to regional security, conflict resolution andprevention and conventional arms control. Georgia hasalso made the most of the mechanism within the EAPC of

calling meetings between the 19 Allies and individualPartner countries, so-called 19+1 meetings, to consultwith NATO on questions of interest for both Georgia andthe Alliance. The first political consultations betweenGeorgia and NATO took place at NATO in spring 2001 atthe level of assistant secretary general for political affairsand deputy foreign minister. The usefulness of these meet-ings demonstrates the potential of the relationship betweenthe Alliance and a Partner, given a genuine will to fostercooperation and understanding.

In recent years, Georgia has given special importance toimplementation of its Individual Partnership Programmewith NATO and participation in the Planning and ReviewProcess, which we joined in 1999. To date, Georgia hasaccepted and is working towards fulfilling 29 PartnershipGoals. We have also has hosted a significant number ofEAPC activities. This includes a regional course on civil-emergency planning and civil-military cooperation in May1997; the first ever EAPC seminar on practical regionalsecurity cooperation in October 1998; the meeting of LandArmaments Group 9 of NATO and Partner countries inOctober 1998; another EAPC workshop on EconomicAspects of Defence Budgeting in Transition Economies inJune 2000; a NATO Science Programme Advisory Panelon Life Science and Technology in May 2001; and a NATOScience Committee meeting in October 2001.

Regional security cooperation in the Caucasus is an areaof EAPC activity which Georgia has consistently spon-sored and is eager to take forward so that both Georgia andthe wider region realise their potential. Since the EAPCBasic Document sets out the possibility of creating specialregional groups, Georgia proposed the formation of a spe-cialised working group on the Caucasus. The initiative wassupported by both Armenia and Azerbaijan, as well asother members of the EAPC and led to the creation of theEAPC Ad Hoc Working Group on Prospects for RegionalCooperation in the Caucasus. This Working Group metformally in Autumn 1999 to explore possibilities of practi-cal cooperation in the region, building on work alreadyundertaken in informal discussions in 1997. It recom-mended a number of activities falling under the followingidentified priority areas: defence economics, civil-emer-gency planning, security-related science and environmen-tal cooperation, information and public relations. TheWorking Group met again in 2000 to take stock of workundertaken in these areas and to consider other possibili-ties for further cooperation.

In the course of the past ten years, both Georgia andNATO have travelled a long way. Through involvement inthe EAPC and by expanding bilateral relations with keyNATO members, Georgia has been able to move political-ly closer to the Alliance and join the process of Euro-Atlantic integration. Clearly, Georgia’s relationship withNATO has already borne much fruit. Yet there is potentialfor an even more fruitful partnership. ■

NATO’S EVOLVING PARTNERSHIPS

Autumn 2001 NATO review 17

NATO review18 Autumn 2001

This approach appears particularlyappropriate in a security environmentas conducive to shaping as today’spost-Cold War Europe. In this fluidsetting, institutions such as NATOare playing a major role in influenc-ing the direction of Euro-Atlanticsecurity. Put differently, institutionshave become agenda-setters. Notonly do they enable collective actionin a crisis, they also foster new secu-rity relationships and thereby addressquestions of Europe’s wider stabilityand even long-term political order.

This exercise in exploring NATO’spotential to shape the Euro-Atlanticsecurity environment of the nextdecade will proceed in three steps. Itwill outline a benevolent scenario for2011; identify some major condi-tions and variables affecting that sce-nario; and make some suggestions asto what NATO must do now to helpachieve the benevolent scenario.

A benevolent scenario 2011Perhaps the most obvious

characteristic of “NATO 2011”is that it will be larger. Afterseveral waves of enlarge-ment, the Alliance will havegrown to 25 or more mem-bers. It will therefore stillhave more members thanan enlarging EuropeanUnion. Even so, the overlap inmemberships will remain closeenough to enable both organisationsto continue their institutional rap-prochement. Fears that NATO’s deci-sion-making process will be undulycompromised by the growth of

Michael Rühle is head of policy planning and speechwriting in

NATO’s Political Affairs Division.

Alliance membership will have beenput to rest. The unique political andmilitary role of the United Statesin Euro-Atlantic security willremain and will continue tohelp ensure a pre-dispositionamong Allies to seek com-mon solutions.

T h eEuropean Union’sambition to develop aEuropean Security and DefencePolicy (ESDP) will have manifesteditself in an even stronger Europeanmilitary role in the Balkans, as well

In 1984, a famed Norwegianpeace researcher came up with alist of what he considered to be

Europe’s most secure states. Hischoice of Switzerland as the numberone was hardly surprising. By con-trast, his choice of second and thirdseemed peculiar even at the time:Albania and Yugoslavia. His reason-ing was as straightforward as it wasworrying. Since NATO and theWarsaw Pact were undoubtedlygoing to war with one another, thosecountries furthest removed from the“military blocs” would have therosiest future.

It may be tempting to belittle thisunfortunate analysis as a typical“period piece” from the early 1980s.Yet, dire predictions about NATO’sfuture have hardly fared better thanpredictions about the Balkans.Although NATO’s current primacy inEuro-Atlantic security may suggestotherwise, only a decade ago theAlliance’s future seemed bleak.Indeed, in the early 1990s, evenstaunch Atlanticists harboureddoubts about the future of an organi-sation that seemed to have accom-plished its mission. Had it been pre-dicted then that, in 1999, NATOwould admit three former WarsawPact members and conduct a pro-tracted air operation in the Balkans,the likely reaction would have beendisbelief or even derision.

Speculating about the futureremains a hazardous undertaking,but one which is nonetheless useful.Even if not every prediction willcome true, the very exercise of fore-casting helps to concentrate the mindon the key issues. It forces thinkingabout a “preferred future”, the meansnecessary to achieve this outcome,and the variables that could interfere.

Imagining NATO 2011Michael Rühle gazes into his crystal ball and imagines how the Alliance and

the Euro-Atlantic security environment might look in ten years.