Narrating Resilience: Transforming Urban Systems Through...

Transcript of Narrating Resilience: Transforming Urban Systems Through...

Narrating Resilience: Transforming UrbanSystems Through Collaborative Storytelling

Bruce Evan Goldstein, Anne Taufen Wessells, Raul Lejano and William Butler

[Paper first received, October 2011; in final form, September 2012]

Abstract

How can communities enhance social-ecological resilience within complex urbansystems? Drawing on a new urbanist proposal in Orange County, California, it issuggested that planning that ignores diverse ways of knowing undermines the experi-ence and shared meaning of those living in a city. The paper then describes how nar-ratives lay at the core of efforts to reintegrate the Los Angeles River into the life ofthe city and the US Fire Learning Network’s efforts to address the nation’s wildfirecrisis. In both cases, participants develop partially shared stories about alternativefutures that foster critical learning and facilitate co-ordination without imposingone set of interests on everyone. It is suggested that narratives are a way to expressthe subjective and symbolic meaning of resilience, enhancing our ability to engagemultiple voices and enable self-organising processes to decide what should be maderesilient and for whose benefit.

Keywords: collaboration, governance, narratives, networks, new urbanism,resilience, sustainability

Introduction

Social ecological resilience, conceived inresponse to the challenges of naturalresource scarcity and degradation, has

migrated to the city to help individuals,communities and organisations to cope withchallenges such as mitigating and adapting

Bruce Evan Goldstein is in the Environmental Design and Environmental Studies Programs,University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, CO 80309-0397, USA. Email: [email protected].

Anne Taufen Wessells is in the Urban Studies Program, University of Washington, Tacoma, 1900Commerce Street, Tacoma, Washington, WA 98402-3100, USA. Email: [email protected].

Raul Lejano is at the University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, S.A.R; as of January 2014, in theEnvironmental Conservation Education Program, New York University, New York, NY 10003, USA.Email: [email protected].

William Butler is in the Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Florida State University,Tallahassee, Florida, USA. Email: [email protected].

Special issue article: Governing for urban resilience52(7) 1285–1303, May 2015

0042-0980 Print/1360-063X Online� 2013 Urban Studies Journal Limited

DOI: 10.1177/0042098013505653

to climate change (Pelling and Manuel-Navarrete, 2011), disaster planning, man-agement and recovery (Goldstein, 2008),energy and environmental security (Coaffee,2008), water management (Pahl-Wastl,2007), integrated land use and transportplanning (Newman et al., 2009), and urbandesign (Colding, 2007). Resilience can serveas a conceptual framework for exploring andenabling new urban possibilities, movingbeyond the goals of recovery or persistencethat characterise much of sustainabilitythinking. Resilience thinking highlights thefutility of predictive forecasts based onassumptions of order, certainty and equili-brium, an ‘engineering’ mode of operationthat is still deeply embedded in planningmethod and practice (Folke et al., 2003).Instead, resilience thinking offers plannerslanguage, ideas and methods that accountfor the non-linearity, uncertainty and intrin-sically dynamic character of complex sys-tems. Yet there is an unresolved tensionbetween resilience as an expression of scien-tific and managerial expertise and the needto engage multiple voices and enable self-organising processes to achieve resilience.

In this paper, we propose a way to resolvethis tension by pursuing resilience throughinclusive planning approaches that enablepeople to tell stories of what change meansto them and how they need to change. Weprovide examples of communities thatdefine system parameters and relationshipson their own terms and act on this knowl-edge to realise their preference among manypossible resilient futures. In previous scho-larship on urban transformation, authorshave emphasised the existence of emancipa-tory practices amid social conflict (Bollens,1999; Friedmann, 1987; Harrison et al.,2008). We extend this area of inquiry to con-sider the potential of collaborative practices.

We begin by defining social-ecologicalresilience as a useful transdisciplinary analy-tical framework for research, while noting

how it is less useful as a guide for commu-nities that seek to enhance resilience. Wealso describe how cities can be understoodas part of dynamic social-ecological systems,rather than as bounded and stable entities.Next, we outline how communities canengage in collaborative construction ofshared narratives that bridge different waysof knowing and bind people together withina shared understanding of their social andnatural world. We consider three cases,beginning with a cautionary tale of anattempt to promote a new urbanist vision inthe Santa Ana neighbourhood, OrangeCounty, USA. This plan was thought to betransformative and hopeful by its propo-nents, yet was perceived as alien and threa-tening by many long-time residents. Ourtwo subsequent cases show how inclusivenarratives enable people to creatively con-struct their own resilient possibilities. Wedescribe how a multicultural communitywas mobilised to reintegrate the Los AngelesRiver into city life; and we describe howecologists, conservationists and land man-agers re-envisioned wildfire managementacross the US by creating a learning net-work. We conclude with ideas about howplanners can engage communities in inclu-sive collective storytelling that can promoteresilience through urban transformation.

Social-ecological Resilience

As a transdisciplinary field, social-ecologi-cal resilience thinking offers an alternativeto Cartesian scientific modernism—theidea that the world is like a clockwork thatcan be ordered, predicted and controlled.Social-ecological systems are complex, dis-continuous, non-linear and unpredictable,integrating human and natural phenomenaacross multiple spatial scales and time-frames. Social-ecological resilience scienceis a transdisciplinary alliance of fields that

1286 BRUCE EVAN GOLDSTEIN ET AL.

at UNIV OF COLORADO LIBRARIES on March 30, 2015usj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

share concepts and concerns that resonatewith a contemporary sense of uncertaintyand insecurity in an era of globalisation,social unrest and ecological limits.Resilience thinking provides a way ofunderstanding how seemingly stable condi-tions that we see around us in nature andsociety can alter, reconfigure and becomesomething new, with profoundly differentcharacteristics (Folke, 2006; Kinzig et al.,2006).

Grounded in this indeterminate world-view, resilience is defined as the capacity torespond to perturbations in ways that main-tain some, but not all, aspects of systemstructure and function (Walker and Salt,2006). The essence of resilience is an abilityto change as circumstances change, to adaptand, crucially, to transform rather than con-tinuing to do the same thing faster andbetter. Social-ecological systems occupy oneof many possible alternative system statesrather than maintaining a single equilibriumwith their surrounding conditions (Folke,2006). The idea that there is a normal systemstate is rejected—if a system transforms afterdisturbance, this is not a failure in resilienceterms, but an inherent possibility withinthat system, one that may help to avoidsystem collapse altogether.

The dynamics of change in social-ecological systems are described as anongoing process of renewal and regenera-tion, using a concept derived from study ofecological succession called the ‘adaptivecycle’. Gunderson and Holling (2002)introduced the term ‘panarchy’ to capturethe idea that adaptive cycles are partiallynested within one another and interactunpredictably across space and time.Panarchy, in deliberate contrast with ‘hier-archy’, suggests that while slow-changing,large-area processes influence nested sub-systems, they do not exercise control overthem—localised actors and processes canself-organise and aggregate to express

emergent, higher-order properties.Panarchy and the adaptive cycle have beenused to critique governance arrangementsthat try to keep conditions stable in orderto maximise output efficiency.

Resilience scholars have taken on thequestion of how communities can plan andmanage amidst ongoing dynamic changewithout the presumption of stability andpredictability (Folke et al., 2010). Theyfocus on how networked and polycentricgovernance can preserve overall systemintegrity by enhancing capacity to adapt inresponse to changing conditions, both interms of generating novel alternatives andmobilising the resources and will requiredto reorganise and transform. Adaptivecapacity is enhanced through collaborativeproblem-solving, social learning and enga-ging a diversity of stakeholders and knowl-edge practices (Armitage et al., 2007; Folkeet al., 2005). In turn, adaptive capacity isgrounded in qualities that include a strongconnection to place, ample social capital,dense social networks and a positive out-look (Goldstein, 2008).

From Cities to Urban Systems

Theorising social-ecological resilience forurban settings requires conceptual displace-ment of the city as a contained and objec-tively knowable space. Urban scholars haveclearly experienced their ‘cultural turn’ andhave long since unsettled the presumptionof incontrovertibly measuring, mappingand otherwise representing the city as a sin-gular object of positivist social scientificstudy. However, willingness to simultane-ously embrace a constructivist ‘scalar turn’has occurred more recently. Leading thecharge have been urban political geogra-phers who, working to theorise the ways inwhich spatial relations are shaped througha politics of scale, recognise the active

NARRATING RESILIENCE 1287

at UNIV OF COLORADO LIBRARIES on March 30, 2015usj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

political construction of and dynamicinterplay between various scales of govern-ance, from the local and regional to thenation-state and global (Jones, 1998;Swyngedouw, 2000).

Conceptualising urban social-ecologicalresilience requires just such a scalar refram-ing, since it is not simply a question of ade-quately capturing the myriad human–natureinteractions that take place within a discretejurisdiction. Urban systems extend farbeyond the physical boundaries of the cen-tral city, which is less reliably central, denseand unitary than ever before. In the US, thegrowing majority of urban residents live indensely populated, suburban-style develop-ments located throughout sprawling, poly-centric metropolitan areas (Knox, 2008),dramatically disrupting early paradigms inhuman ecology and urban ecology such asconcentric rings and linear urban-to-ruralgradients (Alberti, 2005). From a social-ecological systems perspective, distinctionsbetween city, suburb, countryside and wild-erness run the risk of becoming entrenchedaesthetic habits as often as valid empiricalassessments—and, as a result, residents ofurban regions often fail to acknowledge,steward and engage the nature in their midst(Light, 2003), the natural resource systemsthat enable their existence (Cronon, 1991)and the vast appropriative footprint of theirconsumption (Rees and Wackernagel, 1996).

Thus, it is essential that resilience thin-kers move beyond traditional cities towider urban systems as the focus of theori-sation, recognising that these systems oper-ate at various scales that can be functionallynested. Urban scholars have begun toexplore how cities exhibit the cross-scalepatterns and processes associated with com-plex adaptive systems and have proposed arainbow of urban systems neologisms todescribe them, including dissipative cities,synergetic cities, fractal cities, agent-basedcities, cellular automata cities, sandpile

cities and network cities (Portugali, 2010).However, it is also crucial to recognise thaturban scales are socially constructed, cultu-rally maintained and politically contested(Bulkeley, 2005; Jones, 1998; Swyngedouw,2000). Cities are relational accomplish-ments, which matters profoundly to thetheorisation of resilience for urban city-regions.

Resilience Thinking and Worldsof Meaning

The idea that scale is an interactionalachievement resulting from intentions andchoices has not been well developed withinresilience thinking. Instead, resilience ana-lysts have focused on developing analyticaltools to help managers understand social-ecological dynamics and guide systemstoward desirable trajectories by identifyingpossible leverage points for interventionassociated with disturbance regimes, thresh-olds and regime shifts (Walker and Salt,2006). These tools selectively combine thenatural sciences with quantitative, positivistsocial sciences such as economics and insti-tutional analysis to model the complexitiesof human–environment relations. Thechoice of social science approach in suchtools tends further to reify social dynamicsas a natural fact, downgrading the potentialagency of human beings to interpret, learnand change. These efforts are orientedtoward government planners and managerswho need to make decisions about adapta-tion goals without assuming that fixity andcontrol are possible.

However, resilience analysis does notengage with the material, social and sym-bolic landscape that constitutes the livedexperience of the communities whose resili-ence is being sought (Adger et al., 2009;Crane, 2010). Inhabitants of multiethnic,multiracial and multicultural places know

1288 BRUCE EVAN GOLDSTEIN ET AL.

at UNIV OF COLORADO LIBRARIES on March 30, 2015usj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

their cities by experiential, contemplativeand artistic knowledge in addition toscience—what urban planning scholarLeonie Sandercock (2003a) calls an ‘episte-mology of multiplicity’. Resilience analysiscannot capture how resilience is experi-enced through these richly varied ways ofknowing and worlds of meaning (Feldmanet al., 2006; Goldstein, 2010; Lejano andIngram, 2009).

Practical efforts to bridge this divide andassist communities have struggled to makethe concept of resilience meaningful anduseful. For one thing, the ideas are often ascomplex as the phenomena they describe,even for people familiar with the managerialsciences. Implementing one resilience assess-ment, Wilkinson et al. (2010) relates how agroup of environmental planners repeatedlyasked her to translate the basic principles ofresilience into terms they could understand,with one commenting that

The language is opaque. It is actually quite

dreadful . I will be looking at ways to try and

simplify some of the language and make it

more digestible (Wilkinson et al., 2010, p. 37).

More fundamentally, separating assessmentfrom community engagement accepts thepresumption that social-ecological systemsjust exist naturally, ignoring the influenceof epistemic and cultural diversity, normal-ising system dynamics as if they are inevita-ble, obscuring how systems are socially andecologically constructed, and depoliticisingthe value choices that motivate and guidehuman agency (Porter and Divoudi, 2012).Communities need to engage with the sub-jective and symbolic meaning of resiliencein order to be able to decide the specifics ofwhat should be made resilient to which dis-turbances, what are the desired outcomesand whose resilience should have priority,since resilience for some people may lead toloss of resilience for others (Jasanoff, 2008).

Without this awareness, elite and manage-rial preferences for stability and continuitymay remain unexamined, despite being asnormatively inflected and politically andculturally situated as any other configura-tion of resilience (STEPS Centre, 2008).

Resilience and Narrative

The quest for resilience, as with planning,invariably entails envisioning healthy,vibrant communities. However, resilience isnot simply the capacity for change, but anability to adapt without losing the culture,community ties and local traditions thatmake a place home. It is envisioning a kindof change that nurtures communities hereand now without tearing them apart. Thistype of visioning process comes to lifethrough narrative. For our purposes, we canunderstand narrative as simply ‘‘a languageact by which a succession of events havinghuman interest are integrated into the unityof this same act’’ (Bremond, 1973, p. 186).

There is considerable literature in the fieldof planning that has underscored that plan-ning is, as Throgmorton (2003) describes it,persuasive storytelling. Sandercock (2003b)reminds us that not only is an effective plana coherent narrative, but also it is throughthe crafting of the narrative that diverse play-ers find common threads that bind them toa shared vision or that opposing partiesbegin to work out catharsis and healing.Conversely, she points out that factors thatalienate and divide can be traced to flaws ina community’s foundational narrative. If weare to understand the problems that belea-guer a place and identify potential resolu-tions, we have to study emplotment—theway that diverse characters and events aretied into a coherent logical or temporalthread that makes sense to those who arealso part of the story (Lejano et al., 2013).Elements of emplotment include: who tells

NARRATING RESILIENCE 1289

at UNIV OF COLORADO LIBRARIES on March 30, 2015usj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

the story and what is its plot, the centralcharacters in the story, moral themes andlessons, and coherence of its central logic. Acommunity’s foundational narrative, even inits simplest form, is then codified and reco-dified in a stream of planning reports, circu-lars, ordinances and even institutionaldesigns.

Change the story, and you change thecity. As Sandercock (2003b, p. 18) pointsout, stories can be used ‘‘in the service ofchange, as shapers of a new imagination ofalternatives’’. This, too, is a central messageof Finnegan (1998), who provides compel-ling evidence that people act out the storiesthey tell about the city and, indeed, fashionthe city upon these stories. While planningcan be seen as an act of storytelling(Forester, 1999), the stories themselves caninvoke an imagined future, ‘‘not just to talkabout what is, but also what ought to be’’(Schon and Rein, 1975; quoted in vanHulst, 2012, p. 300).

Resilient cities need a coherent founda-tional narrative (Sandercock, 2003b) thatenvelops concerns of those affected andweaves these concerns into a credible storythat resolves issues and ties people together.However, in this essay, we explore the possi-bility that these stories need not be all-encompassing metanarratives (Schon andRein, 1995). Good narratives capture andrepresent many different voices and areamenable to being told by each in theirunique way (Bruner, 1990). These plurivo-cal narratives are partially shared, allowingfor differences in perspective, storyline andfocal point and enabling different sectors ofa community to tell in their own voice howthey belong to the city ( Lejano et al., 2013).Planning can engage multiple resilient alter-natives when those who experience the citycan co-construct their own stories (vanHulst, 2012). Planning is then less aboutauthoritative guidance and more of a meansfor communities to take turns creating and

retelling partially shared stories and weavingtogether a collective life out of their authen-tic lived experience (Lejano and Wessells,2006).

Three Cases

We now present three cases that illustratehow narration can define and even help toachieve resilience. These cases each emergedfrom the authors’ own engagements withvarious communities and each case drama-tises particular aspects of our understandingof resilience narratives. The first case, inSanta Ana, California, is a cautionary tale ofhow even the most carefully crafted plan-ning narrative can disenchant when it isgiven and not shared. The second case, theLos Angeles River (LAR) restoration initia-tive, illustrates how informal social net-works can emplot a plurivocal narrative thatbinds together widely disparate interests.The third case, the Fire Learning Network(FLN), illustrates how a networked colla-borative process enabled creation of narra-tives that were both situated in the localcontext and coherent enough to bind thefire community to a larger shared purpose.

Barrio Santa Ana

Santa Ana, California’s recent ‘RenaissancePlan’ is an example of state-of-the-artdowntown redevelopment and a pivotpoint from which we consider departuresfrom normal planning practice. The projecttook a New Urbanist approach to refa-shioning an older downtown area seen tobe economically stagnant (City of SantaAna, 2007). The Renaissance plan envi-sioned a utopian ideal of walkable streets,mixed uses, higher-end establishments anda picturesque New Urbanist architecturaltemplate. This is a visionary counterpointto what Santa Ana has been, an older neigh-bourhood of Orange County, California,

1290 BRUCE EVAN GOLDSTEIN ET AL.

at UNIV OF COLORADO LIBRARIES on March 30, 2015usj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

home to a traditionally majority-Latinocommunity (78 per cent Hispanic: USCensus Bureau, 2010). Adjacent to higher-end municipalities like Irvine and NewportBeach, Santa Ana remains primarily alower-income working-class communitywith a per capita income of $16,613 and thenation’s ninth-highest population density(US Census Bureau, 2010).

There is language in the Renaissance Planthat evokes resilience thinking

Cities are dynamic and ever-changing places

that experience many cycles of growth over

time. Cities with long and distinguished his-

tories, such as Santa Ana, often find them-

selves needing to guide this change so that

existing strengths can be reinforced and

appropriate change can be realized (City of

Santa Ana, 2007, p. 1:1).

The goals of the Renaissance Plan werebroadly appealing—improve employmentand income prospects for both current andincoming residents and attract a variety ofbusinesses that would be resilient againstglobal economic downturns. The plan’s

vision of walkable streets, mixed uses andlow-intensity forms is codified in a regulat-ing plan and detailed set of form-basedcodes that specify rather determine archi-tectural and geometric templates. As arguedin the text of the plan

This plan works in every way to recognize and

enable traditional neighborhood develop-

ment of varying intensities, including transit-

oriented and commercial districts, through a

tailored vision, policies and regulations. This

plan is based on a set of integrated principles

that have produced the best places and cities

throughout the world (City of Santa Ana,

2007, p. 1:7).

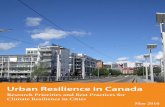

Previous analysis (Gonzalez and Lejano,2009) critiqued the strong universalist NewUrbanist template that is being applied todiverse neighbourhoods throughout thecountry. The same analysis found that thenature, look and culture of the presentneighbourhood, such as the culturallyimportant La Cuatro district (see streetscene in Figure 1), were hardly representedin the new plan. In the terms we have laid

Figure 1. La Cuatro distict, Santa Ana, California.Photo: reproduced with permission from Erualdo Gonzalez.

NARRATING RESILIENCE 1291

at UNIV OF COLORADO LIBRARIES on March 30, 2015usj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

out in this article, the plan did not exhibitplurivocity.

In one of the few mentions of SantaAna’s predominantly Latino community,the Renaissance Plan states

Downtown Santa Ana is a thriving commercial

district located in one of the wealthiest coun-

ties in the United States and offers a broad

range of goods and services focused primarily

towards the Hispanic community. The down-

town’s few but influential ‘one-way’ streets and

limited left turns restrict local accessibility and

likely frustrate potential shoppers. The north-

east quadrant of the plan area has direct fron-

tage to I-5 and the Santa Ana interchange that

would be attractive to regional and national

retailers but not necessarily the same that

would be attracted to downtown. Santa Ana is

surrounded by a wide range of demographics,

including many high income households (City

of Santa Ana, 2007, p. 1:2).

The plot of the narrative, then, rests on thenotion of a stagnant present condition andan unfulfilled promise that stems from theuntapped reservoir of consumer demandfrom interests not presently found in SantaAna. The plan then spells out a vision forclaiming a higher position in OrangeCounty and, in the plan’s language, becom-ing a transit-oriented district that couldbecome ‘Orange County’s downtown’.

While the Renaissance Plan formallyinvolved a design charette and more than ahundred public sessions, it incurred resent-ment from some community residents,businesses and advocates. Anti-redevelop-ment sentiment was easily found—in onecase, residents wore pins that said ‘‘StopEthnic Cleansing!’’ (Gonzalez et al., 2012).One local writer, pondering over the archi-tectural styles encoded into the plan, wrote

Notice a pattern? With the exception of the

last one (which is the preferred style for

overpriced lofts nationwide), each had its

heyday before World War II—which, in

SanTana history, was a time when everything

was wonderful and the darkies and brownies

couldn’t enter certain restaurants, had to live

in certain neighborhoods, and got to go to

the balcony to see movies (Arellano, 2010).

These statements are indicative of a sense ofalienation. Gonzalez and Lejano express it inthese terms

The term ‘Renaissance’ invokes not just

rebirth but, consistent with new urbanist

tenets, a reclamation of glories of the past.

. references to the past in narrative, form,

and image refer largely to history preceding

World War II before the transition of Santa

Ana to a largely Spanish-speaking, immi-

grant, and working-class city (Gonzalez and

Lejano, 2009, p. 2956).

The appeal to the myth of a golden age orparadise lost is often found in policy narra-tives, especially those of renaissance.However, as de Neufville and Bartonpointed out, myths can also

provide rationalizations that turn attention

away from theory and intractable issues,

uncomfortable realities, and discrepancies

between public values and actual conditions

(de Neufville and Barton, 1987, p. 184).

Not that the downtown redevelopment plandid not have strong advocates in the com-munity (discussed in Rojas, 2011). Some feltthat early changes, such as the artists’ village,were positive (Nasser, 2005). Yet the plan,its language and narrative, did not reflectthe diverse voices and lived experiences ofits residents. It is not evident how designcharettes and public hearings in Santa Anaallowed community any significant voiceover the design (Gonzalez and Lejano,2009). Researchers question the absence of

1292 BRUCE EVAN GOLDSTEIN ET AL.

at UNIV OF COLORADO LIBRARIES on March 30, 2015usj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

measures specific to the needs of the existingworking class or the preservation of cher-ished elements of the barrio (Gonzalez andGuadiana, 2012). This absence leads us tothe ask what practices might enable com-munity members to place themselves withina preferred resilient future and then act tobring this future into being, questions whichwe consider next.

Los Angeles River Restoration

In a case that is perhaps emblematic ofsocial and ecological tensions faced by the21st-century coastal city-region, the LosAngeles River serves to illuminate the waysthat scales of governance essential to urbanresilience are understood and enactedthrough narratives. The recent movementto renew the river’s role as a life-giving ele-ment in the social and ecological systems ofthe urban region (Wessells, 2010) is occur-ring through a shift in the scales at whichthe river is known, experienced and gov-erned. One way to understand this shift isby considering the river narratives thatemplot individuals and communities withinparticular relationships.

The move to engineer, channelise andencase the river in concrete was accompa-nied in the second half of the 20th centuryby the construction of a foundational nar-rative (Sandercock, 2003b) that paints thewatercourse as capricious, threatening anddestructive to the interests of human resi-dents throughout the region. A flood-pronestream in the midst of a rapidly urbanisingregion, the river frightened citizens andruined them financially when its ragingwaters destroyed infrastructure and prop-erty in the early 1900s. A longtime residentrecalls that his parents ‘‘went down to theLA River, and counted houses, floatingdown the river during the floods’’ (KCET,2012). Residents were shocked by the ‘‘deep

rushing water that seemed almost to threa-ten our feet’’ (Bartlebaugh, 2011) and calledfor its taming and control. This unifyingnarrative maps onto and reinforces a gov-ernance scale at the level of the region andthe nation-state. The river’s devastatingecological force is a basin-wide phenom-enon, socially constructed as a national eco-nomic threat warranting the intervention ofthe US Army Corps of Engineers in the1930s (see Gumprecht, 1999). Through thisfoundational narrative, local citizens ‘scaledup’ responsibility for and relationship withthe river and assented to the external con-trol, if not outright erasure, of the river as aliving element in the social ecology of theregion.

Cracks in the foundational narrativeemerged half a century later, when artistsand non-profit activists started a movementin the mid 1980s to reclaim the river, pled-ging to ‘‘speak for it in the human realm’’(MacAdams, 1995)—implicitly pointing tothe collective narrative function underlyingurban natural resource management. Theriver movement in Los Angeles has sincegrown into a robust network of individualand organisational actors, including gov-ernment, non-profit, business, activist andneighbourhood groups. This growth hasbeen accompanied by narratives that recon-struct the local governance scale as signifi-cant and meaningful, and emplot multiplecitizen voices into relationship with theriver.

Deconstructing the foundational narra-tive is itself a storytelling move, acknowled-ging the abnegation of social-ecologicalresponsibility that takes place by pushingthe scale of river governance off to federalflood control engineers: the city had ‘turnedits back on the river’ (see for example,Golding, 1998). Such a turning-away actionsignifies a broken relationship with thework, uses and livelihoods that the riveronce supported, as well as with the

NARRATING RESILIENCE 1293

at UNIV OF COLORADO LIBRARIES on March 30, 2015usj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

sustaining health and vitality of the riversystem and natural environment. Thisrhetorical move indicts and thus engages abroad network of urban interests and actors.It is a call to action common to the riverrevitalisation movement around the world;the implied next step in the narrative arc isa turning toward the river, a righting ofwrongs, a facing, re-engagement andtransformation.

New narratives, guiding the turning ofcitizens towards the river, are still underconstruction (Wessells, 2007). This recon-struction is broadly signalled by the forma-tion and implementation of the Los AngelesRiver Revitalization Master Plan, a processwhich began in 2005 with the official riverbooster imperative to turn from back-to-front, and ‘‘transform our river from aneglected backyard to a beautiful and wel-coming front yard’’ (Reyes, 2004; see Figure 2for a possible river future from this plan).The yard metaphor promises plurivocity, asopposed to the imposition of a singular,manicured interpretation.

This is evident in a recent collaborationbetween the Los Angeles River RevitalizationCorporation, founded to support the imple-mentation of the 2007 Master Plan, with the

local public television station, KCET.Through a series of events, programmes andonline spaces, KCET has helped to collect,curate and present the stories of dozensof urban citizens seeking to define andemplot themselves into the river’s emergingnarrative.1 In so doing, they are reconstruct-ing the scale of governance where the river isunderstood and managed, and restoring notits native ecology—not yet—but rather thehuman relationships with the river at theregion’s centre. In these narratives, urbancitizens recognise and celebrate a river that isreal to them, at the immediate, local scale.According to one local activist, workingwith each of these communities is essentialto the Revitalization Master Plan’s success

You got developers, you got architects . but

the river touches so many communities .Get each community to give its own flavor,

its own touch, that really gets people to feel

like, this is ours (Rodriguez, 2011).

As more citizens of the urban region articu-late a story of their relationship to the river,and the scale of governance where the riveris managed is reconstructed to becomeincreasingly local and variegated, the new

Figure 2. Alternative future of the urban flood control channel.Source: Los Angeles River Revitalization Master Plan (2007); Mia Lehrer + Associates, WenkAssociates, Inc. and Civitas, Inc.

1294 BRUCE EVAN GOLDSTEIN ET AL.

at UNIV OF COLORADO LIBRARIES on March 30, 2015usj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

narratives reflect a sense of urban nature asless external and distant and more familiarand knowable. As a Los Angeles UrbanRanger puts it, while the natural world is fre-quently treated by urban citizens as some-thing ‘‘out there, like Yosemite’’, cominginto contact with the river builds a ‘‘sense ofwonder and discovery, of your everydaylandscape’’ (KCET, 2012). The river seemsto reframe various individuals’ expectationsof urban natural resources and, as a result,their sense of connectedness to a wider eco-logical web: a participant on an eveningfieldwalk noted, ‘‘My impression of the LARiver has always been a bad one . but I’venoticed the wildlife, and the goodness of it’’(KCET, 2012); and a resident reflecting on aplay staged in the river pointed out

We didn’t really think too much about the

environment—that’s someone’s else’s job,

that’s not ours, we live in the city—and then

realizing, we all need to be part of this

(Dominguez, 2011).

The emerging plurivocal narrative does notnecessarily replace the foundational story ofthe river’s extraordinary regional floodpotential—if anything, ongoing urbanisa-tion and more frequent extreme weatherevents have increased this danger—butrather, unsettles and complements this uni-tary narrative, with its external locus ofcontrol and responsibility, with a moreporous and experiential scale of recognitionand relationship. Thus, the local networksof river governance are reconstructed asmeaningful to the thousands of citizenswho must ultimately enact the region’s resi-lience, or lack thereof.

Fire Learning Network

While the Los Angeles River case studydemonstrates the potential of emergent andplurivocal narratives to unify and direct

collective action without explicit planningco-ordination, our next case illustrates amore purposeful effort to create a sharednarrative in order to mobilise a communityto action within a broader matrix of institu-tional deadlock. The case shows how plan-ners can design collaborative settings wherenarrative construction can take place, aswell as facilitate interaction within andbetween communities who are co-ordi-nated for a common purpose, despite theabsence of direct social interaction or geo-graphical proximity. While this narrativeformation is more structured than the stor-ies of the LA River basin, the emplotmentof characters, places and actions throughtime gave rise to plans that were coherentwith a co-ordinated logic about restorationwhile remaining plurivocal and animatedby local conditions and values.

The case examines the US Fire LearningNetwork (FLN), an effort led by the USForest Service (USFS) and The NatureConservancy (TNC) to reorient fire man-agement toward ecological restoration andcommunity protection (Butler andGoldstein, 2010; Goldstein and Butler,2009, 2010a, 2010b). The FLN focuses onwildlands and the human settlements attheir borders or scattered within. These set-tlements have a tense relationship to adja-cent wildlands not only because they mightalso be burned, but also because they relyon forest products, direct employment,housing and recreational opportunities,and ecosystem services such as watersupply. As with flooding of the Los AngelesRiver, burning is a fundamental processthat highlights the interconnection andmutual interdependence of social-ecologi-cal systems.

The FLN began after a series of destruc-tive wildfires in the early 2000s, whichincreased federal funding and willingness totry new approaches to restoring fire-adapted ecosystems. FLN’s co-ordinators

NARRATING RESILIENCE 1295

at UNIV OF COLORADO LIBRARIES on March 30, 2015usj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

organised hundreds of fire managersaround the nation into landscape-scalelearning co-operatives that spanned any-where from tens of thousands to millions ofacres (see Figure 3), across jurisdictions andownerships. For example, the Onslow Bightlandscape in North Carolina covers morethan 1.3 million acres and includes landsmanaged by the Department of Defense,USFS, TNC, North Carolina State Parks,North Carolina Department of WildlifeResources and the US Fish and WildlifeService, and encompasses towns and cities,including Wilmington, Jacksonville andNew Bern.

Using structured planning exercises, FLNco-ordinators guided participants in eachlandscape through emplotment, construct-ing narratives that situated partners withinan arc of conflict, crisis and resolution(Goldstein and Butler, 2010b). Participantswere encouraged to draw on the best avail-able science as well as practical managerial

knowledge to develop these restorationplans. Each landscape’s narrative was pat-terned on a ‘golden age lost’ archetype thatbegan before European colonisation, whenboth aboriginal and naturally ignited firesmaintained healthy forests. Fire exclusionthroughout the 20th century then broughton decline, changing the composition andstructure of ecosystems and raising the riskof catastrophic fire. Battalions of firefighterson the front lines of wildfire fall from gracewhen viewed through this ecological lens.In the present, ecosystems were portrayedas altered beyond their capacity to recoverwithout help. Positioning themselves at thislow point in the narrative arc, fire managersdeveloped two alternative futures. One sus-tained the status quo of fire suppression,increasing risk of fire and further degradingecological health. The other restored natu-ral fire regimes.

The moral tension of these fire stories layin choosing between complicity through

Figure 3. Active US FLN landscapes and regions in 2012.Source: courtesy of FLN Director.

1296 BRUCE EVAN GOLDSTEIN ET AL.

at UNIV OF COLORADO LIBRARIES on March 30, 2015usj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

inaction versus righting past wrongs byundoing a century of fire suppression.Planning documents developed by eachlandscape collaborative described institu-tional barriers to fire restoration as principalobstacles on the path to improved ecologicalconditions, and fire managers were cast askey agents of change. Protagonists of theirown story, fire managers developed strate-gies to remove administrative barriers sothat they could judiciously apply fire to pro-tect communities and heal landscapes.Implementation of their plans would com-plete the narrative archetype of ‘golden agerestored’, as fire managers reclaimed theheroic identity denied to them within thedeclensionist narrative of fire suppressionand forest decline.

As managers redefined the meaning ofprofessional practice, they regained a senseof common purpose and orientation foraction. Storytelling helped to forge acommon purpose, develop a shared reper-toire of knowledge and skills, and lay thegroundwork for collaboration by requiringmanagers to work together across jurisdic-tions (Goldstein and Butler, 2009, 2010b).FLN’s co-ordinators reinforced these con-nections by publicising exemplary effortsand providing shared tools for spatial anal-ysis and display. Common tools and analy-tical frameworks helped FLN landscapes tounderstand one another’s stories and thisfamiliarity gave participants a sense thatthey were part of a national community,despite not knowing all the members of thefar-flung network (Goldstein and Butler,2009).

The FLN fostered resilience by buildingsolidarity around a new professional iden-tity, developing skills and knowledge to sup-port that identity and creating relationshipsthat increased collective capacity. The FLN’s‘golden age restored’ narratives were pluri-vocal across landscapes, while coherent witha co-ordinated effort to develop plans to

renew ecosystem functions. The learningnetwork began to alter the deeply engrainedinstitutional culture built around fire sup-pression by enhancing each landscape’s abil-ity to understand the often subtle and deeplyrooted obstacles to pursuing alternativesand begin reconfiguring responsibility andaccountability so that change could occur.

Resilience Narratives

Considered together, our three cases showthat a crucial part of collaborative storytell-ing is determining what to make resilient,what are desired outcomes and what areobstacles to achieving these preferences.Collaborative planning stories are bothdescriptive and normative, making sense ofthe world while providing guidance forchange amidst turbulence and uncertainty(van Hulst, 2012). A plurivocal storytellingframework allows people to tell an inclusivestory that takes into account distinct cir-cumstances and situated knowledge whilefacilitating connection among diverse parti-cipants operating in different places.

Taken simply as a long collection ofspecifications, the Santa Ana new urbanistRenaissance Plan posed few problems. Yetit was a different matter when we peeredinto the foreboding meanings that thesespecifications for gentrification had forsome residents. Part of its threat lay in itsunivocality—by not allowing counter-nar-ration, the Renaissance Plan only allowedresidents to defend a status quo that theymay wish to change, given an opportunityto imagine alternatives. The case illustrateshow generalised templates for enhancingresilience through transformative changecan undermine the experience and sharedmeaning of those living in a city. Displacingthe focus from political ‘what to do’ ques-tions to technical ‘how to’ questions, thesestories erase differences while reinforcing

NARRATING RESILIENCE 1297

at UNIV OF COLORADO LIBRARIES on March 30, 2015usj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

mutually beneficial relationships betweenplanners and the powerful. Resilience maybe diminished through the myopia of plan-ners following the latest utopian ideal in afield whose history has been defined bysuch idealism.

Our two subsequent cases illustrate thatknowledge required for resilience is bothparticular to a community and is expressedand reshaped collectively. The stories of amisguided past and envisioned transforma-tion in the future that emerge from theFLN and LA River cases were more than ameans to pursue system guidance throughdata gathering, analysis and selection of anoptimal alternative. Participants relied on aplurivocal narrative framework to engageone another and identify shared goals. Asthey explored possibilities for change, theydeveloped a better understanding of theconstraints and dependencies that shapedtheir conception of what was possible toachieve. The temporal and spatial contextand positioning of their stories enabledeach community to develop new relation-ships and revise assumptions underlyinginstitutional norms, rules and practices.Their narratives enhanced possibilities forresilience by providing a framework forreshaping both knowledge and knowers.

In LA, a river had become an eyesorethat exacerbated flash floods within its con-crete channels and swept rainwater out tosea in a region renowned for water scarcity.However, these crises and concerns couldnot bring stakeholders together to promotechange until they began to talk about howthey would ‘turn toward’ the river.Stakeholders began to rethink the river’smeaning and use in terms that made senseto themselves as flood control engineers,economic development officials, neigh-bourhood leaders, recreation advocates andsocial justice activists. An essential featurewas this story’s open and undefined charac-ter, which could engage a multitude of

perspectives from a variety of settings. Thesuccess of river advocates in shaping a plur-ivocal narrative underscores the power ofstory to promote resilience across the scalesof a ‘panarchy’, engaging different levelswithout attempting to compel centralisedco-ordination.

Differences within and between thelandscapes of the Fire Learning Networkalso had stymied efforts to reorient firemanagement toward ecological fire restora-tion, despite recognition that fire suppres-sion often increases fire incidence andmagnitude, ecological harm and commu-nity vulnerability. Forging ‘golden age lostand restored’ narratives in each landscapeenabled complementarity across widely dis-persed landscapes. Fire managers were con-scripted in their landscape’s particularnarrative of decline and redemption whileconnecting them to a greater whole as theyidentified with the roles, values and knowl-edge of ecological restoration. Coherencewas not a product of an integrated plan,but rather an emergent quality of a nation-wide collection of plurivocal narratives.Joint storytelling disrupted old assumptionsand engendered new routines, laying thegroundwork for institutional change byenabling fire managers to speak autono-mously with a unified voice.

These cases show that resilience as situ-ated in community action is better under-stood as a process or relationship ratherthan a property—one that can be framed topermit alignments and divergences betweendifferent perspectives. Urban communitiesenhance resilience by making sense of theirpresent conditions and possible futures,combining collaborative problem-solvingcoupled with reflective analysis-in-action(Lewin, 1946) to accommodate diverseknowledges and align on a shared futurewithout eliding essential differences.Plurivocal narratives are partially shared,allowing for differences in standpoint,

1298 BRUCE EVAN GOLDSTEIN ET AL.

at UNIV OF COLORADO LIBRARIES on March 30, 2015usj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

characters and plot. As they tell their stor-ies, participants reconfigure individual andcollective identity by revising their relation-ships with each other and reshaping theirknowledge and assumptions.

Roles for Planners

Considered together, the LA and FLN casesunderscore that planners can help commu-nities to create resilience narratives thatguide efforts to recombine existing struc-tures and processes and promote systemrenewal and emergence of new trajectories.The skills that planners have developed tofacilitate stakeholder-based collaborationcan also help to enhance resilience throughcollaborative storytelling, since good facili-tation can promote trust and empathy, anunderstanding of interdependencies andcapacity for individual and social learning(Kaufman, 2011). In addition, new networkfacilitation skills are needed to promotecommon narratives across space and time,tying together disparate sites, organisationsand jurisdictions. Both cases provide exam-ples of this kind of network leadership. Thenon-governmental organisation Friends ofthe Los Angeles River (FoLAR) helped tolink seemingly disparate river activities bysimultaneously engaging in the languageand work of activism, technical researchand governmental action. The FLN was amore actively facilitated effort at promotinga common narrative. Rather than imposinguniformity by prescribing interactionamong participants, FLN co-ordinatorsengaged in what one called ‘‘netweaving’’,travelling across the network to providetechnical assistance and enhance cross-siteconsistency and communication.

In addition to providing facilitationskills, organisers often need to help commu-nities operate effectively in the politicalmargins, using techniques that are less

state-oriented and managerial and moreakin to the struggles of social movements.As the resistance of old-guard fire managersand the early years of river activism in LosAngeles attest, even weakened institutionscan blunt efforts to pursue social-ecologicalresilience when changes threaten the pero-gatives of the powerful (Allison and Hobbs,2004). In addition to challenging elite pre-ferences for stability and continuity thatmay be embedded in the status quo, plan-ners can help communities to engage withdifferent kinds of resilience and identifywhose resilience should have priority. Whatis needed in Santa Ana may be a visioningeffort that can challenge the powerful visionof New Urbanist renewal with a counternar-rative of community resilience and rebirththat enables residents to tell partially sharedstories and weave together their experiencesinto a collective life.

Conclusion

Social-ecological resilience informs plan-ning at the dynamic interface of persistence,adaptation and transformation. This flexibleresponse to uncertainty and discontinuitycan help to chip away at the assumptionsabout equilibrium, forecasting, predictabil-ity and control that stubbornly hang on inplanning theory and practice. Resiliencethinking also enables us to highlight thecritical impact and dependence of cities onecosystem processes. Lack of attention tothese linkages between urban needs andecological functions such as soil, climate,freshwater supply and biodiversity has ledto degradation so extreme that many pastcities were abandoned altogether (Grimmet al., 2000). Concerns are now emerging ata different scale as we push the planet out ofits current stable state, the Holocene periodthat began with the first permanent settle-ments 10,000 years ago. As we move into

NARRATING RESILIENCE 1299

at UNIV OF COLORADO LIBRARIES on March 30, 2015usj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

the Anthropocene, cities will be where mostdecisions and actions occur that impactclimatic, geophysical, atmospheric andecological processes that define critical‘hard-wired’ thresholds in the Earth’senvironment outside which existing socialand ecological systems cannot function(Rockstrom et al., 2009).

We argue that narrative is an essential ele-ment in the formulation and maintenanceof urban systems. Narratives help to definethe scale at which socio-natural relations areexperienced, understood, enacted and sus-tained, as in the Los Angeles case; and theycan transcend and move across scales in away that enables dramatic shifts in the ratio-nales and practice of natural resource man-agement, as in the Fire Learning Networkcase. Urban resilience signals a capacity toself-organise at various scales and to adjustbehaviour in order to adapt to and trans-form emergent conditions—including thescale of appropriate action. Stories are car-riers of our interpretations and rationales,and help us to account for how our urbanworlds are arranged as well as how theymight be deliberately adjusted and trans-formed (Lejano et al., 2013). Narrativesenable human actors to do this across vari-ous ways of knowing and existing patternsof action, making them particularly power-ful and accessible (Lejano et al., 2013).Moreover, narratives can articulate a collec-tive identity that transcends spatial and tem-poral limits, shaping a community ofotherwise disparate voices into a coherentand plurivocal vision of the future(Goldstein and Butler, 2009).

While this article has underscored thelimits of analytical resilience thinking as ameans to engage communities, we do notdo this in order to detract from the funda-mental spirit of the enterprise. On thecontrary—we are arguing that interpretiveplanning research is a necessary addition toresilience as a transdisciplinary field if

resilience scholars and practitioners want tounderstand urban systems and informtransformative change, an objective that isirreducibly political and conflictual. Systemsanalysts provide useful diagnostic tools inthis setting, working with communities tohelp describe adaptive cycles and regimeshifts, to identify memory in the system thatcan help restart cycles and to enumeratedrivers of change and disturbance events.However, communities need to tell theirown stories in order to identify systemproperties that are meaningful and compel-ling and enhance their personal and collec-tive agency. They need to decide what willbe made resilient, what are desired out-comes, whose resilience should have priorityand who plays what role in transformingthings for the better.

Funding

This research was made possible in part throughfunding by the Northern Research Station of theUS Forest Service and The Nature Conservancy.

Note

1. See for example, a city-wide competition,‘‘Songs of the LA River’’; http://lariversonger.posterous.com.

References

Adger, W. N., Dessai, S., Goulden, M.,Hulme, M. et al. (2009) Are there sociallimits to adaptation to climate change? Cli-matic Change, 93, pp. 335–354.

Alberti, M. (2005) The effects of urban patternson ecosystem function, International RegionalScience Review, 28(2), pp. 168–192.

Allison, H. E. and Hobbs, R. J. (2004) Resilience,adaptive capacity, and the ‘lock-in trap’ of theWestern Australian agricultural region, Ecol-ogy and Society, 9(1), art. 3.

Arellano, G. (2010) Santa Ana’s re-renaissanceplan wants to Marty McFly us back to thepast!, OC Weekly, 24 March.

1300 BRUCE EVAN GOLDSTEIN ET AL.

at UNIV OF COLORADO LIBRARIES on March 30, 2015usj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Armitage, D., Berkes, F. and Doubleday, N.(2007) Introduction: moving beyondco-management, in: D. Armitage, F. Berkesand N. Doubleday (Eds) Adaptive Co-management, pp. 1–15. Vancouver, BC:University of British Columbia Press.

Bartlebaugh, Y. (2011) Before it was carpetedwith cement, KCET, 4 April (www.kcet.org/socal/departures/community/before-it-was-carpeted-with-cement.html; accessed 28 May2012).

Bollens, S. A. (1999) Urban Peace-building inDivided Societies: Belfast and Johannesburg.Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Bremond, C. (1973) Logique du Recit. Paris: Seuil.Bruner, J. S. (1990) Acts of Meaning. Cambridge,

MA: Harvard University Press.Bulkeley, H. (2005) Reconfiguring environmen-

tal governance: towards a politics of scalesand networks, Political Geography, 24(8), pp.875–902.

Butler, W. H. and Goldstein, B. E. (2010) The USFire Learning Network: springing a rigiditytrap through multi-scalar collaborative net-works, Ecology and Society, 15(3), art. 21.

City of Santa Ana (2007) Santa Ana renaissancespecific plan. Moule & Polyzoides Architectsand Urbanists, Santa Ana, CA.

Coaffee, J. (2008) Risk, resilience, and environ-mentally sustainable cities, Energy Policy,36(12), pp. 4633–4638.

Colding, J. (2007) Ecological land-use ‘comple-mentation’ for building resilience in urbanecosystems, Landscape and Urban Planning,81, pp. 46–55.

Crane, T. A. (2010) Of models and meanings:cultural resilience in social-ecological sys-tems, Ecology and Society, 15(4), art. 19.

Cronon, W. (1991) Nature’s Metropolis: Chicagoand the Great West. New York: WW Norton.

Dominguez, C. (2011) The great river, KCET,30 April (www.kcet.org/socal/departures/community/neighborhoods/la-river/the-great-river-by-cecilia-dominguez.html; accessed 26May 2012).

Feldman, M. S., Khademian, A. M., Ingram, H.and Schneider, A. S. (2006) Ways of knowingand inclusive management practices, PublicAdministration Review, 66(6s), pp. 89–99.

Finnegan, R. (1998) Tales of the City: A Study ofNarrative and Urban Life. Cambridge: Cam-bridge University Press.

Folke, C. (2006) Resilience: the emergence of aperspective for social-ecological systems anal-yses, Global Environmental Change, 16(3), pp.253–267.

Folke, C., Carpenter, S. R. and Walker, B. (2010)Resilience thinking: integrating resilience,adaptability and transformability, Ecology andSociety, 15(4), art. 20.

Folke, C., Colding, J. and Berkes, F. (2003) Synth-esis: building resilience and adaptive capacityin social-ecological systems, in: F. Berkes, J.Colding and C. Folke (Eds) Navigating Social-ecological Systems: Building Resilience for Com-plexity and Change, pp. 352–387. Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.

Folke, C., Hahn, T., Olsson, P. and Norberg, J.(2005) Adaptive governance of social-ecolo-gical systems, Annual Review of Environmentand Resources, 30, pp. 441–473.

Forester, J. (1999) The Deliberative PlanningPractitioner: Encouraging Participatory Plan-ning Processes. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Friedmann, J. (1987) Planning in the Public Domain.Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Golding, A. (1998) The Los Angeles River: reshap-ing the urban landscape. Los Angeles Riverconnection (www.laep.org/target/units/river/riverweb.html).

Goldstein, B. E. (2008) Skunkworks in theembers of the Cedar fire: enhancing resili-ence in the aftermath of disaster, HumanEcology, 36(1), pp. 15–28.

Goldstein, B. E. (2010) Epistemic mediation:aligning expertise across boundaries withinan endangered species habitat conservationplan, Planning Theory and Practice, 11(4),pp. 523–547.

Goldstein, B. E. and Butler, W. H. (2009) Thenetwork imaginary: coherence and creativitywithin a multiscalar collaborative effort toreform U.S. fire management, Journal of Envi-ronmental Planning and Management, 52(8),pp. 1013–1033.

Goldstein, B. E. and Butler, W. H. (2010a)Expanding the scope and impact of colla-borative planning, Journal of the AmericanPlanning Association, 76(2), pp. 238–249.

Goldstein, B. E. and Butler, W. H. (2010b) TheU.S. Fire Learning Network: providing a nar-rative framework for restoring ecosystems,professions, and institutions, Society and Nat-ural Resources, 23(10), pp. 935–951.

NARRATING RESILIENCE 1301

at UNIV OF COLORADO LIBRARIES on March 30, 2015usj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Gonzalez, E. and Guadiana, L. (2012) Culturallyoriented downtown revitalization or creative gen-trification? Unpublished working manuscript.

Gonzalez, E. and Lejano, R. (2009) New urban-ism and the barrio, Environment and PlanningA, 41(12), pp. 2946–2963.

Gonzalez, E., Sarmiento, C. and Luevano, S.(2012) The grassroots and new urbanism: acase from a southern California Latino com-munity. Unpublished working manuscript.

Grimm, N., Grove, J. and Pickett, S. (2000) Inte-grated approaches to long-term studies ofurban ecological systems, BioScience, 50(7),pp. 571–584.

Gumprecht, B. (1999) The Los Angeles River: ItsLife, Death, and Possible Rebirth. Baltimore,MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Gunderson, L. H. and Holling, C. S. (Eds) (2002)Panarchy: Understanding Transformations inHuman and Natural Systems. Washington,DC: Island Press.

Harrison, P., Todes, A. and Watson, V. (2008)Planning and Transformation: Learning from thePost-apartheid Experience. London: Routledge.

Hulst, M. van (2012) Storytelling, a model of anda model for planning, Planning Theory, 11(2),pp. 299–318.

Jasanoff, S. (2008) Survival of the fittest, inre-framing resilience: a symposium report.Paper presented at the Re-framing ResilienceSymposium, Brighton.

Jones, K. T. (1998) Scale as epistemology, Politi-cal Geography, 17(1), pp. 25–28.

Kaufman, S. (2011) Complex systems, anticipa-tion, and collaborative planning for resilience,in B. E. Goldstein (Ed.) Collaborative Resili-ence: Moving through Crisis to Opportunity,pp. 61–98. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

KCET (2012) LA river ramble: entering the back-country of Los Angeles, 26 January (www.kcet.org/socal/departures/landofsunshine/production-notes/la-river-ramble.html; accessed 26 May2012).

Kinzig, A. P., Ryan, P. A., Etienne, M., Allison, H.E. et al. (2006) Resilience and regime shifts:assessing cascading effects, Ecology and Soci-ety, 11(1), art. 45.

Knox, P. L. (2008) Metroburbia USA. New Bruns-wick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Lejano, R. and Ingram, H. (2009) Collaborativenetworks and new ways of knowing, Environ-mental Science and Policy, 12(6), pp. 653–662.

Lejano, R. P. and Wessells, A. T. (2006)Community and economic development:seeking common ground in discourse and inpractice, Urban Studies, 43(9), pp. 1469–1489.

Lejano, R., Ingram, M., and Ingram, H. (2013)The Power of Narrative in EnvironmentalNetworks. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Lewin, K. (1946) Action research and minorityproblems, Journal of Social Issues, 2(4), pp.34–46.

Light, A. (2003) Urban ecological citizen-ship, Journal of Social Philosophy, 34(1),pp. 44–63.

MacAdams, L. (1995) Restoring the Los AngelesRiver: a forty-year art project, Whole EarthReview, 85.

Nasser, E. H. (2005) ‘New Urbanism’ embracesLatinos, USA Today, 5 February.

Neufville, J. I. de and Barton, S. E. (1987) Mythsand the definition of policy problems: anexploration of home ownership and public–private partnerships, Policy Sciences, 20(3),pp. 181–206.

Newman, P., Beatley, T. and Boyer, H. (2009)Resilient Cities: Responding to Peak Oil andClimate Change. Washington, DC: IslandPress.

Pahl-Wastl, C. (2007) Transitions towards adap-tive management of water facing climate andglobal change, Water Resources Management,21(1), pp. 49–62.

Pelling, M. and Manuel-Navarrete, D. (2011)From resilience to transformation: the adap-tive cycle in two Mexican urban centers,Ecology and Society, 16(2), art. 11.

Porter, L. and Divoudi, S. (2012) The politics ofresilience for planning: a cautionary note,Planning Theory and Practice, 12(2), pp.329–333.

Portugali, J. (2010) Statis is data: toward a com-plexity theory of resilient cities. Paper presentedat the Resilient Cities, AESOP ComplexityWorking Group.

Rees, W. and Wackernagel, M. (1996) Urbanecological footprints: why cities cannot besustainable—and why they are a key to sus-tainability, Environmental Impact AssessmentReview, 16(4–6), pp. 223–248.

Reyes, E. P. (2004) Public letter seeking supportfor the L.A. River revitalization plan. City ofLos Angeles.

1302 BRUCE EVAN GOLDSTEIN ET AL.

at UNIV OF COLORADO LIBRARIES on March 30, 2015usj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Rockstrom, J., Steffen, W. and Noone, K. (2009)A safe operating space for humanity, Nature,461(7263), pp. 472–475.

Rodriguez, L. (2011) LA River field guide: voiceson recreation (www.kcet.org/socal/departures/fieldguides/lariver/; accessed 13 April 2012).

Rojas, J. B. (2011) Will Latino-led redevelopmentin Santa Ana ultimately rob it of its Latino-ness?, 29 March (http://www.scpr.org/blogs/multiamerican.scpr.org/2011/03/will-latino-led-redevelopment-in-santa-ana-ultimately-rob-it-of-its-latino-ness/).

Sandercock, L. (2003a) Cosmopolis 2: MongrelCities. New York: Continuum.

Sandercock, L. (2003b) Out of the closet: theimportance of stories and story-telling inplanning practice, Planning Theory and Prac-tice, 4(1), pp. 11–28.

Schon, D. A. and Rein, M. (1995) Frame Reflec-tion: Toward the Resolution of IntractablePolicy Controversies. New York: Basic Books.

STEPS (Social, Technological and Environmen-tal Pathways to Sustainability) Centre (2008)Reframing resilience: transdisciplinarity, reflex-ivity and progressive sustainability. STEPSCentre Symposium, Brighton, January.

Swyngedouw, E. (2000) Authoritarian govern-ance, power, and the politics of rescaling,

Environment and Planning D, 18(1), pp.63–76.

Throgmorton, J. A. (2003) Planning as persua-sive storytelling in a global-scale web of rela-tionships, Planning Theory, 2(2), pp. 125–151.

US Census Bureau (2010) State and countyquickfacts: Santa Ana. Washington, DC: USGovernment Printing Office (http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/06/0669000.html;accessed 16 December 2012).

Walker, B. H. and Salt, D. (2006) ResilienceThinking: Sustaining Ecosystems and People ina Changing World. Washington, DC: IslandPress.

Wessells, A. T. (2007) Constructing watershedparks: actor-networks and collaborative gov-ernance in four U.S. metropolitain areas. Uni-versity of California, Irvine, CA.

Wessells, A. T. (2010) Place-based conservationand urban waterways: watershed activism inthe bottom of the basin, Natural ResourcesJournal, 50(2), pp. 539–557.

Wilkinson, C., Porter, L. and Colding, J. (2010)Metropolitan planning and resilience think-ing: A practitioner’s perspective, CriticalPlanning (Summer), pp. 25–44.

NARRATING RESILIENCE 1303

at UNIV OF COLORADO LIBRARIES on March 30, 2015usj.sagepub.comDownloaded from