Music of Sound and Light

Transcript of Music of Sound and Light

5/14/2018 Music of Sound and Light - slidepdf.com

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/music-of-sound-and-light 1/12

Leonardo

Music of Sound and Light: Xenakis's PolytopesAuthor(s): Maria Anna HarleySource: Leonardo, Vol. 31, No. 1 (1998), pp. 55-65Published by: The MIT PressStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1576549 .

Accessed: 27/10/2011 02:51

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range o

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new form

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

The MIT Press and Leonardo are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Leonardo.

5/14/2018 Music of Sound and Light - slidepdf.com

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/music-of-sound-and-light 2/12

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

M u s i c o f S o u n d a n d L i g h t :

Xenakis's Polytopes

Maria Anna Harley

IN A MUSICAL UNIVERSE

And whenI lookedup at theinfinite sky,theuniversecontem-

platedmefromits emptyand bottomlessrbit .. theuniverse's

edifice garnished with a thousand suns, like a cavern en-

sconced n eternallight, where uns shine likeminer's anterns

and milkywayslike silverveins.

Jean-Paul Richter [1]

These words introduced the spectacle of LeDiatope 1979), an

audiovisualwork by Iannis Xenakis that incorporated an archi-tectural shell, electroacoustic music and a mobile-light display.Similar evocations of cosmic phenomena are not uncommon

in the writingsof this Greek composer and architect, who once

described the process of composing music as analogous to

navigating a "cosmicvessel sailing in the space of sound, across

sonic constellations and galaxies"and explained human intel-

ligence in the language of astrophysics [2]. Xenakis the archi-

tect believed that the evolution of humanity had reached a cos-

mic stage requiring new forms of dwellings, such as his "cosmic

city,"an unrealized project intended to "bringthe populationin contact with the vast spaces of the skyand of the stars"[3].

Xenakis the composer marked the beginning of this new

"planetaryand cosmic era"in human development by invent-

ing a new form of multimedia art that he called the "polytope"

[4], from the Greek polys (many, numerous) and topos (place,

space, territory, location). The polytope is based on the idea of

a great space consisting of many smaller elements, a domain of

spatial complexity that may be articulated by sound and lightin movement. According to Xenakis, the polytope "experi-ments with novel waysof using sound and light. It's an attemptto develop a new form of art with light and sound" [5].

Xenakis explains that in creating this art form he was "at-

tracted by the idea of repeating on a lower level what Nature

carries out on a grand scale. The notion of Nature covers not

only the earth but also the universe"[6].

THE PHILIPS PAVILION

AND LE GESTEELECTRONIQUE

Xenakis's first personal encounter with multimedia extrava-

ganzas took place during work on the Philips Pavilion at the

1958 World Exposition in Brussels-the site of Edgar Var&se's

and Le Corbusier's Poeme lectroniqueFig. 1) [7]. This unique

spectacle consisted of two independently created layers: an

Maria Anna Harley (musicologist), Polish Music Reference Center, School of Music,

University of Southern California, 840 West 34th Street, Los Angeles, CA 90089-0851,

U.S.A.

E-mail: <[email protected]>.

electroacoustic composition byVarese and a visual display by Le

Corbusier. The prophetic lan-

guage and technical novelties of

Poeme ontinued the tradition of

Universal Expositions (alsoknown as World Expositions or

EXPOs), which were designed as

celebrations of human domi-

nance over nature. The Exposi-tions' spirit of ascendancy over

natural powers has been appar-ent in their presentations of the

most recent scientific inventions

ABSTRACT

Thisarticlexploresheadiovisualnstallationsf Greek

composernd rchitectanniXenakis,ocusingn heworkhecalls"polytopes."heerm

polytopeaptureshecompleofthespatial esigns ndmul

tiple paces ftheseunusua

light-and-soundorks, hichoften sed housandsf ightsandhundredsf oudspeakeXenakis'solytopesre xamin heir estheticnd ulturatext;hediscussionf thisorignal orm favant-gardert n-cludes

surveyf ts

orms,functionsnd eception.

and architectural projects of their times, including such land-

marks as the Crystal Palace in London (1851) and the Tour

d'Eiffel in Paris (1889). In Brussels in 1958, the immense

Atomium (a model of the atom) symbolized the newly discov-

ered power of nuclear energy. For EXPO '58, Xenakis-then

working as an architect for Le Corbusier-was given the job

of designing a pavilion to display the technological achieve-

ments of the Philips Corporation from 1956 to 1958 [8]. The

young artist was also asked to compose a brief piece of

musiqueconcreteo

providean introduction to the electronic

poem by Varese and Le Corbusier. The result was the elec-

troacoustic miniature ConcretPH, which filled the curved

spaces of the Pavilion with the "organic life and chemical

flavour" of the sounds of burning charcoal [9]. The title of

this piece refers to key elements of the Pavilion's architec-

ture: the material of reinforced concrete and the basic shapesof hyperbolic paraboloids. In Musique.Architecture,Xenakis

described the Pavilion as "a dawn"of a new architecture that

was to be based on the bending rather than the shifting of

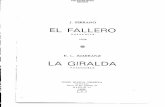

Fig. 1. Xenakis's sketch of the external shell of the Philips Pavil-

ion (Brussels, 1958). Notice the bending of the surfaces and two

tops towering above the structure.

LEONARDO, Vol. 31, No. 1, pp. 55-65, 1998 55? 1998 ISAST

5/14/2018 Music of Sound and Light - slidepdf.com

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/music-of-sound-and-light 3/12

surfaces [10]. Indeed, the use of sur-

faces of variable curvature, such as pa-raboloids and conoids, became his artis-

tic signature: the surfaces sculpted the

sounds in the orchestral work Metastasis

(1953-1955) and provided the architec-

tural framework for the Polytope de

Montreal (1967).

At the Brussels exposition, the peaked

pavilion with smooth walls of reinforced

concrete covered with tiles (Fig. 1)

housed a spectacle of sound and images.Varese's musical composition (music for

tape projected from more than 400

loudspeakers) and Le Corbusier's visual

display (slides and light show) were per-formed simultaneously, but had been

created independently of each other. Le

Corbusier had originally intended to

read fragments of his poems praising

technological progress and the conquestof "the mathematical universe" as a partof the Poeme electronique [11]. Because of

difficulties coordinating this textual

layer with the music, however, instead

he included the poetry excerpts in the

program book. Rather than adding the

spoken word to the spectacle, he used

visual means to narrate a tale of human

frailties and triumphs at the beginningof what he called "a new civilization, a

new world" [12] made possible by the

progress of science. Such was the gen-esis of "lesjeux electroniques"-a new

form of electronic art envisioned by Le

Corbusier as incorporating elements of

"light, colour, rhythm, motion and

sound" [13]. This definition, included

in the program book of the Poeme

electronique, id not specify any details.

In any case, Xenakis was dissatisfied

with the narrative form and mimetic

content of Le Corbusier's spectacle, with

its realist imagery of Aztec sculptures,

portraits of children and people at work,and photographs of skulls, rockets and

heavy machinery. He also considered the

absence of cooperation between the two

authors-Le Corbusier and Varese-and

the fact of its double authorship to be

the work's essential weakness. He

thought that this form of art should have

a single creator who would unite dispar-ate elements by his or her coherent artis-

tic vision. In 1958, Xenakis described

this concept in an article that became

the blueprint for the polytope [14]. This

technological art form was to bring to-

gether the concept of abstract paintingwith the techniques of cinema, combin-

ing colored mobile backgrounds, shift-

ing spatial configurations and patterns, a

play of colors and forms, and abstract

music. According to Xenakis, the pro-cess of musical "abstraction" onsists of a

shift towardatonality; t also relies on the

appropriation of concrete sounds and

the creation of electronic sonorities and

their organization into vast sonic ges-tures [15]. In the geste electronique total,

spatial locations as well as pitches, dura-

tions, timbres and dynamic levels are in-

herent to the structure. The architec-tural shell of the performance spaceshould assume a new, irregular form al-

lowing for multiple images to be dis-

played at the same time in different geo-metric transformations, criss-crossingand permeating each other. Xenakis

wanted the visual display to sever all con-

nections with the mimetic realism im-

plied by flat screens that resemble the

two-dimensional canvas of the tradi-

tional painting. Instead, the whole vol-

ume of the performance space was to be

filled with sounds and images.Xenakis's emphasis on the composi-

tional use of the spatial properties of

sound has a precedent in the writings of

Pierre Schaeffer, the pioneer of musiqueconcretewho, in the early 1950s, intro-

duced the idea of the movement of

sound along trajectoires onores (sonic tra-

jectories) [16]. This term referred to

imaginary paths traced by mobile sound

images that emanate from static loud-

speakers and travel around a perfor-mance space. Schaeffer utilized two

types of spatial sound projection with

multiple loudspeaker systems-static re-

lief and kinematic relief, the latter of which

involved mobile sound sources whose

movement was controlled by hand ges-tures of the performers. This wayof cre-

ating "spatialrelief' in music was heard

for the first time during a concert ofSchaeffer and Pierre Henry on 6 July1951 in Paris, when Symphonie pour un

homme seul and Orphee 51 were per-formed [17]. Xenakis reformulated

these concepts as stereophonie statique

(sound emanating from numerous

points dispersed in space) and

stereophonie cinematique (sound whose

sources were both multiple and mobile).

Here, Xenakis imagined that by the pre-cise definition of sound source loca-

tions, geometric shapes and surfaces

might be projected into the area of per-formance. These geometric sound enti-ties would arise from the succession and

simultaneity of sound images playedback from loudspeakers located in the

auditorium. If, for instance, the same

sonority was performed in succession

and with a slight overlap from several

loudspeakers, it would create a triangu-lar sound pattern. If many short im-

pulses were heard, they could-depend-

ing on their placement in time and

space-create a sonic surface. One can

multiply these examples to demonstrate

how an auditory space could be struc-

tured by means of abstract morphologi-cal principles. Xenakis's use of the lan-

guage of geometry-points, lines and

surfaces-to discuss aural phenomenahas parallels in contemporaneous litera-

ture of the musical avant-garde [18] and

precedents in theoretical manifestos of

abstract painting such as Kandinsky'sPoint and Line to Plane (1913) [19].

Fig. 2. Xenakis's

sketch of the loca-

tion of his Polytopede Montreal n theinterior of the

French Pavilion at

EXPO 67 in

Montreal.

POLYTOPE EMONTREAL,1967In 1966, Xenakis

finallyhad a chance to

realize his dreams of this new form of

electronic art. He received a commission

to prepare a sound-and-light perfor-mance in the French Pavilion at EXPO

67 in Montreal [20]. The general theme

of this exposition, Terredes Hommes (Manand his World), which was borrowed

from a book by Antoine de Saint-

Exupery, encompassed a number of sub-

jects, all celebrating human achieve-

ments in controlling and transforming

56 Harley,Music of Sound and Light: Xenakis's Polytopes

5/14/2018 Music of Sound and Light - slidepdf.com

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/music-of-sound-and-light 4/12

the Earth [21]. The documents of the

Canadian EXPO Commission (pub-lished in the EXPO program book) lo-

cated science at the center of human ac-

tivity, with an awareness of its victories

(e.g. conquest of space) and dangers

(e.g. threats of global disasters and total

annihilation in atomic war). The orga-nizers hoped that, in addition to reveal-

ing a tremendous faith in progress, the

exhibition would also express human

solidarityon Earth- "thisone tiny speckfixed in the vastness of the universe," in

the words of Quebecois writer Gabrielle

Roy [22]. The theme of solidarity was

obvious in the emblem of the EXPO: a

circle of human figures with arms ex-

tended to the sky,symbolizing the unityand cooperation of all people on Earth.

In accordance with its glorification of

technology, the EXPO transformed the

landscape of Montreal: the construction

work used 22 million tons of rocks to

enlarge one island (St. Helene) and cre-

ate another (Notre Dame) that was,with

an area of 400 hectares, twice as big asthe city of Brussels. Set in a park amidst

newly built canals, fountains and lakes,the pavilions housed exhibits from indi-

vidual countries and large international

organizations. They also featured special

displays, such as an international collec-

tion of fine artscelebrating the theme of

human creativity.Given the exhibition's emphasis on

progress and the conquest of the uni-

verse, the choice of Xenakis to create an

audiovisual installation in the French

Pavilion was notsurprising.

The build-

ing, designed by Jean Faugeron (andawarded the Grand Prix de Rome), con-

tained exhibits on the theme of "Tradi-

tion and Invention" thatjuxtaposed clas-

sic and modern works of art with recent

discoveries made in the fields of science,medicine and technology, among them

the color television. The pavilion in-

cluded several floors of display rooms,all opening onto the central plaza-asuitable location for Xenakis's audiovi-

sual project. Instead of a slide show that

would cast images of crystals into space

to a musical accompaniment (as sug-gested by the commission), the com-

poser designed his first polytope. He

planned five nets of steel cables that out-

lined intersecting shapes of conoids and

hyperboloids in the interior of the pavil-ion (Fig. 2). The linearity of this designreflected the geometry of the building's

characteristic "Venetian-blind"patterns.In Xenakis's project, however, the archi-

tecture was transparent, serving as a

framework for the display of an abstract

composition of moving points of light.The nets of cables supported 1,200

lights, 800 of them white and 100 each

of red, blue, green and yellow. The light

patterns changed every quarter second

and evoked, due to the persistence of

the image on the retina, various configu-rations in motion: arabesques, spirals,

layered patches, nebulae, cascades, gal-axies, explosions, streams and constella-

tions of the stars. The colored lights

were distributed over the five surfacesand gradually emerged from the orga-nized chaos of white light patterns [23].

Xenakis wrote in the program for this

spectacle that his "totalexperience with

musical composition was used here to

serve light composition: probability,

logical structures, group structures, etc."

[24]. The multitude of lights outlined

complex surfaces, created fixed fields or

clouds and moved along the trajectoriesof spirals, circles or complicated curves

in three dimensions. The rhythms of

these movements were constructed with

the help of simple logical operations(sums, differences). Indeed, one might

saythat if the whole EXPO 67 wasmeant

to present, in the words of Gabrielle

Roy, "a thousand pictures, a thousand

sounds whereby we catch a glimpse, a

reflection of the infinity which is our

universe," then Xenakis's polytope

brought this infinity under the roof of

one pavilion.The composed spectacle of automa-

tized patterns of light in movement was

accompanied by continuous music com-

posedof

slowly shifting glissandi.This

composition remains in Xenakis'scatalogunder the title of Polytopede Montreal;t

wasscored for four identical orchestrasof

11 musicians each, with the orchestras

placed at the four cardinal points of the

concert area. (The recording of this com-

position used in the numerous Montreal

performances was prepared in Paris bythe Ars Nova ensemble under Marius

Constant.) During the EXPO perfor-mances, the tape resounded from four

groups of loudspeakers placed at the bot-

tom of the central plaza, below the sus-

pended nets of cables and lights. The uni-formityof the timbre of the four identical

groups of instruments and the symmetryin spatial location was meant to contrast

with the pointillistic light show. The con-

trast was further increased by the conti-

nuity of the music's vast glissandi, which

stretched across the ranges of all the in-

struments.Because the show ran continu-

ously and was visible from all the displayrooms on the various floors of the pavil-ion, members of the public had a chance

to experience it from a number of differ-

ent perspectives during their visits to the

French Pavilion.According to Maryvonne

Kendergi, the audiences included many

young composers from Quebec who were

greatly impressed with this work [25].Micheline Coulombe-Saint Marcoux, for

instance, considered the "perfect symbio-sis of architectural space and musical

structures" as the polytope's most note-

worthyaspect [26].

The automation of the Polytope deMontreal posed many technical prob-lems. The spectacle was controlled bymeans of an ingenious device: indi-

vidual lights switched on after rays of a

continually shining light filtered

through holes in a perforated control

tape and activated signals from a board

of photosensitive cells. For the 6-minute

spectacle, Xenakis calculated 19,000 suc-

cessive light events in order to "create a

luminous flow analogous to that of mu-

sic issuing from a sonic source" [27].This procedure was rather cumbersome

and instilled in the composer a cravingfor complete automation, so that

a newand rich workof visualart couldarise,whose evolutionwould be ruled

by huge computers,a totalaudiovisualmanifestationuled n itscompositionalintelligence bymachinesservingothermachines,whichare, thanks o the sci-entificarts,directedbyman [28].

The yearning for "machines servingother machines" in the creation of a spa-tial music of light seems to have resulted

from the tedious experience of calculat-

ing "byhand" the multitude of

light pat-terns for the Polytopede Montreal. This

dream eventually found its realization in

the Polytope de Cluny of 1972-1974,which is discussed later in this article.

FROMMONTREALTO

PERSEPOLIS

From EXPO 67, Xenakis gained a repu-tation as a creator of enormous audiovi-

sual spectacles. These projects were

partly displays of the newest technologyand partly artistic extravaganzas; they

brought him, in turn, to Iran (1969), toJapan (1970) and to Iran once again(1971). All three projects were con-

nected to the cultural ambitions of the

Emperor of Iran, Shah Mohammed

Reza Pahlavi.

The first of these projects joined mod-ern technology with the archaic gran-

deur of the ruins of Persepolis. The

Shah decided to restore the splendor of

the Iranian dynasty to its former glory.He portrayed himself as the successor to

Harley,Music of Sound and Light: Xenakis's Polytopes 57

5/14/2018 Music of Sound and Light - slidepdf.com

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/music-of-sound-and-light 5/12

the ancient Persian rulers and the

leader of a "WhiteRevolution,"bringingto Iran speedy modernization and social

reforms [29]. The revival of non-Islamic

Persian culture was an important ele-

ment in the Shah's agenda, which in-

cluded such bold steps as changing the

calendar to mark the putative foundingof the first Iranian kingdom. To stimu-

late the interest of the international ar-

tistic community in ancient Persian cul-

ture, the Shah and the Empress FarahPahlavi selected the site of Persepolis for

the annual Shiraz Festival (Shiraz is the

oasis closest to the site of the ancient ru-

ins of Persepolis, located amidst the

desert sands).The remains of the buildings in this

secluded fortress contained symbols of

the Persian dynasty'sabsolute power: re-

liefs of tribute-bearers and inscriptions

praising the king's greatness adorned

the walls [30]. In 331 B.C., Alexander

the Great conquered the Persian Em-

pire and destroyed the palace. The site

was deserted for the next 2,000 years.The first festival was initiated by the

Empress; it took place in 1969 and in-

cluded the premiere of Xenakis's

Persephassa [31]. The Empress envi-

sioned the festival as "ameeting place of

East and West"bringing together tradi-

tional performances with classical the-

ater and avant-garde arts. The audi-

ences, consisting of Iranian peasants,intellectuals and representatives of the

international press, were treated to ex-

perimental theater productions by play-

wrights such as Peter Brook andJerzyGrotowski and modern music byKarlheinz Stockhausen and Xenakis.

Following the success of Persephassa,he

chose Xenakis to design an audiovisual

installation for the Iranian Pavilion at

EXPO 70 in Osaka,Japan, and to create

and direct a gigantic sound-and-light

performance for the opening night of

the 1971 Shiraz Festival,which was held

once again in the ruins of the palace of

the ancient Persian kings at Persepolison 26 August 1971.

At EXPO 70, the "futuristic"architec-

ture was even more inventive than it had

been in Montreal. There were three

enormous geodesic domes and an arrayof pavilions housing audiovisual spec-tacles by avant-garde composers.Stockhausen's series of "intuitivemusic"

performances drew crowds to the Ger-

man Pavilion; many visitors were also at-

tracted to a display of moving laser

beams accompanying the electroacous-

tic music of Toru Takemitsu.

?\ -.:-.r.. ';?0\o . ,'-.'? '* -:`\\\ O

Fig. 3. Fragment of the blueprint for Persepoliswith Xenakis's handwritten annotations

specifying the positions of the loudspeakers, the control area, the audience and the em-

press. The blueprint was annotated during the composer's sojourn in Aspen, Colorado.

Lasers were also featured prominentlyin the Japanese pavilion, for which

Xenakis composed Hibikihanama(1970).The spatial projection of this electroa-

coustic work (made from instrumental

sonorities, including Japanese instru-

ments) used 800 loudspeakers in 250

groupings surrounding the audience. On

display in the building, which was deco-

rated by Joan Mir6, were mobile film-

and-laser works byJapanese artist KeijiUsami, who strictly coordinated the mo-

tions of visual patterns with the three-di-

mensional movement of sound images.The laser displays captured the attention

of many viewers, particularlyof Xenakis,who was ever eager to experiment with

new equipment. Consequently, he went

on to use two laser beams in the Polytope

of Persepolis the work's original title) in

Iran (1971) and made lasers the instru-

ments of choice in both the Polytopede

Clunyand LeDiatope 1978).The 1971 festival belonged a series of

events marking the 2,500th anniversaryof the Persian monarchy-an extrava-

gant celebration replete with fireworks,

military parades, re-enactments of

scenes from the palace reliefs and luxu-

riousparties

for an internationalarrayof royal guests. The opulence of these

festivities caused widespread criticism,

especially among the Moslem clergy,and increased the resentment of the Ira-

nian people against their rulers [32].The people rejected the "occidentosis"

of their monarchs-the admiration and

imitation of Europe that underlay the

introduction of Western-stylefestivals of

the arts to their country [33].

At the historic site, the distinguished

public (including nine kings, five queensand 16 presidents [34]) was located in

the great courtyard (Fig. 3) between the

tombs of Darius and Artaxerxes. The

dignitaries were surrounded by loud-

speakers emitting the continuous,

strange sonorities of Persepolis-an hour-

long electroacoustic piece for 8-track

tape [35]. In a diagram that delineates

the relationships among his composi-tions up to 1974, Xenakis includes

Persepolis n a group of pieces for tape

(along with Hibiki hanama, Polytopede

Montreal nd Polytope eCluny).These are

connectedby

Xenakis to Bohor(1962),an electroacoustic composition charac-

terized by two main traits: "microstruc-

tures" and "spatialization"[36]. Bohor s

textural, with minute transformations

within its dense sonorous masses that are

often made up of brief, overlapping seg-ments of sound material. In Persepolis,the sounds were also "spatialized" bymeans of their projection from numer-

ous loudspeakers dispersed among the

ancient ruins. The blueprint for the

spectacle (Fig. 3) indicates the locations

of 91 circuits for lighting effects scat-

teredthroughout

the ruins of thepalace,as well as eight loudspeakers (markedA-

H) arranged in an irregular semicircular

pattern around the public. The listeningarea was located outside the palace walls

and, judging from the placement of the

sound and lighting equipment, the audi-

ence was expected to look toward the

palace. Xenakis indicated the location of

59 loudspeakers (plus 10 backups), the

control center (postede commande)and

58 Harley, Music of Sound and Light: Xenakis's Polytopes

5/14/2018 Music of Sound and Light - slidepdf.com

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/music-of-sound-and-light 6/12

the privileged central position of the

Empress (Reine)within the palace's col-

onnades and courtyards.The loudspeak-ers, divided into sets of 8 and 16, en-

closed three adjacent audience areas;

here, the spectators were surrounded by

sound.The music accompanied a spectacle

of luminous patterns evoking the Zoro-

astrian symbolism of light as eternal life

[37]. Diffuse light shone on the two

tombs while two laser beams and many

spotlights brightened the night sky.Two

immense fires burned on the hilltops;hundreds of children carried torches to

create moving light trajectories in space.The torch lights formed geometricaland irregular patterns on the mountain

slopes as the children walked in proces-sion to reach the summit of the hill,

then descended and dispersed. At theend of the performance, two groups of

children converged near the tombs and

waved their torches in the air to write a

shiny inscription: "wecarry the light of

the earth." Xenakis coined this phrasein Farsiin an allusion to the Zoroastrian

religion, an ancient Iranian belief sys-tem. This was the spectacle's only con-

crete, programmatic moment; the rest

was a sequence of abstract events that

followed a structural logic unrelated to

historical narrative.

It is still not clear whether

Persepoliscould be called a polytope in the true

sense of the word-that is, a complexand machine-assisted audiovisual spec-tacle that might be performed repeat-

edly (thanks to sound-recording technol-

ogy and the automation of visual

display). The importance of live per-formers for the creation of massive light

patterns in Xenakis's Iranian project and

the uniqueness of its single performance

Fig. 4. A sketch byXenakis for Polytopede Cluny hows the

location of pointsand rays of light in

the ruins of the an-cient Roman baths

at the Cluny Mu-

seum in Paris.

at the great anniversary celebration of

the emperor indicate a need for creatinga separate category to describe Persepolis.Maurice Fleuret groups it with the Greek

project of 1978 Polytopede Mycenesas a

"mass celebration" [38]. However, the

position of the Iranian spectacle inXenakis's oeuvre-between the poly-

topes of Montreal and Mycenes-justi-fies this label, which wasalso used by the

artist during the work's creation. The

title PolytopedePersepolis ppears, for in-

stance, on the blueprint for the

performer's location within the ancient

ruins of Persepolis. The composer drew

from the Persepolis experience when de-

signing the spectacles for the ruins andmonuments of Mycenes; he also in-

cluded dramatic images of the fires

burning at Persepolis in the program

book of LeDiatope,another 1978 work.

POLYTOPEDE CLUNY,1972-1974The polytopes realized in Montreal in

1967 and at the Cluny Museum in Paris

in 1972 were separated by the social un-rest of 1968. In 1968, Xenakis, the most

radically "modern" composer living in

France at the time [39], became one of

the symbols of French students' strugglefor change. One of the slogans of the stu-

dent demonstrations ofMay

1968 de-

manded "Xenakis not Gounod" [40]. In

October 1968 Xenakis's music was fea-tured at Les Journees de musique

contemporaineeParis(along with workbyVarese,Luciano Berio and Pierre Henry)[41]. All concerts were sold out and

many listeners found their way into the

concert halls by defying security guards[42]. Most of these listeners were youngstudents from the generation revolting

against the repressive society of their

forebears [43]. Fleuret explains the sud-

den popularity of contemporary music

with such student audiences as resultingfrom their revolutionary fervor: tired of

the established conventions and rules of

life, the young people chose spontaneity,

informality and novelty. They sought

"spirit, fight, passion" [44] and chosemusic that transcended the limits of tra-

dition and nationalism by posing issues

common to the entire planet. They re-

jected the ritual of concert going with its

formal apparel and conventions of be-

havior [45]; they sat on the floor, sur-

rounded by strange sonorities and sub-

jecting themselves to perceptual and

aesthetic experimentation. They had

ample opportunities for that in Xenakis's

largest audiovisualproject, the Polytope e

Cluny-again, a part of LesJournees de

musique ontemporaineeParis (SIMP).The automated work for light and

sound opened on 13 October 1972 for

16 months of performances that re-

peated four times each day, attractingcrowds of Parisiansand tourists. Accord-

ing to Fleuret, more than 90,000 peoplevisited the Polytopede Clunyduring the

initial period of its exposition [46]; after

the spectacle was redesigned (1973) and

revived (1974), the total audience

reached over 200,000 participants. The

Cluny Museum, whose T-shaped vaults

once housed Roman baths, is located in

the Latin Quarter, ust off Boulevard St.

Germain, in the heart of the city's uni-

versity district [47]. This is the oldest

monument in Paris,and its ancient stone

walls had to be protected during the in-

stallation; Xenakis had a scaffoldingbuilt for the sound and light equipment.The informal performance environment

of this experimental work allowed visi-

tors to sit or lie on the floor in the un-

usual space and admire the technologi-cal innovations. The lasers-then

associated with revolutionary tools and

dangerous weapons rather than ubiqui-tous household appliances-kindled a

particular fascination. Xenakis used

three laser rays (red of krypton, greenand blue of

argon)and 600 xenon flash-

bulbs. The directions of the lasers were

controlled remotely and their rays re-

flected in 400 mirrors to form complex

configurations in space; the mirrorswere

able to change their orientation to dif-

ferent planes, and all the light patternswere automated and controlled by com-

puters. Here, the composer finally real-

ized his dream of harnessing "machines

serving other machines" to create novel

Harley, Music of Sound and Light: Xenakis's Polytopes 59

( t

^r

.T*E

'

. , . . . . .- 3 : tZ ? -I ?

?-..:?~ .-~ :.'.- ...... ,..' .. " ?* *...

-.* * .. ... -..: .

m ^^'-:L{'^ ^^

"

q,X BtSt v .*." -.':. . - .- . - . . .. -*' . * * *-'. .- _'' .-.

^'- ''...:..

:'. .. L/..;-:--' ~._ .,,:- l.

~,. :; : -: . ,.. . . . . . . . . . .. . .;. ., -- -. . . *, .. . . ..-G

K- *

^I-.'"

:

"

'

.

-i.;....: ,

~L^+ :.- ... ._-, : .--...--.:---;

' x

5/14/2018 Music of Sound and Light - slidepdf.com

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/music-of-sound-and-light 7/12

art. The computational prowess of the

IBM and Ampex machines used for the

work was impressive for the time: the 26-

minute spectacle required 43,200,000 bi-

nary commands to control the state of

the lights, the lengths of the laser beams

and the positions of the mirrors. The

commands were encoded on the eighthtrack of the magnetic tape, which con-

tained seven tracks of music. Thus, the

movements of light could be coordi-

nated with the flow of sound. There areseveral important differences between

the projects of Montreal, Cluny and the

later Diatope (1978). Xenakis describes

them in the following words: "In

Montreal I used 600 floodlights, in Clunyas many flashlights, and in the Diatopeas

many as 1,600. The most important dif-

ference is that in Montreal I achieved

the visual effect through film, while in

ClunyI used digital magnetic tape" [48].In Montreal, Xenakis had created a

contrast between the aural and visuallay-ers of his work byjuxtaposing the linear

continuity of the sound with the discrete,

pointillistic effects of the lighting; at

Cluny,however,both the visual and aural

strata included continuous and discrete

events. Numerous combinations of recti-

linear images were precisely controlled:

groups of multi-colored raysshone along

parallel and intersecting paths, forming

triangles and stars in continuous trans-

formation. These images were created

from multiple reflections of laser beams

that combined to produce a series of

mobile light arcs. The points moved in

synchronic and asynchronic rhythms (as

in the Polytopede Montreal), creating liq-uid streams of light, shifting clouds and

rotating columns, aggregates of lines,circles and ellipses (Fig. 4). This mayseem like a visuallesson in Euclidean ge-

ometry, but some patternswere intended

to distantly resemble various natural

phenomena such as the lotus or

anemone-at least that is what Xenakiscalled them in his sketches (Fig. 5).Other pointillistic images evoked the ex-

pansion and collapse of galaxies, the aus-

tere beauty of the cosmos. Interestingly,the initial title of the whole project, La

Riviere, s a testimony to this inspirationfrom the beauty of nature-filtered, as it

often was in Xenakis'swork, through the

language of mathematics.

At Cluny, the music remained simple,its varying pulses and modulating tim-

bres providing a counterpoint to the

density of the lights [49]. The palette of

sounds includes sonorities of non-West-ern provenance, such as recordings of

African drums, juxtaposed with timbral

extremities of the modern orchestra and

computer-generated synthetic sounds

calculated at Centre d'Etudes de

Math6matiqueet Automatique Musicales

(CEMAMu), ounded byXenakis in 1965

[50]. In 1972, digital sound synthesiswas

still so much of a novelty that the sounds

themselves were supposed to be of the

Fig. 5. Xenakis's sketches for the "anemone" light pattern in Polytopede Cluny.The patternis created by laser beams reflecting off mirrors placed on the scaffolding in the perfor-mance space. As the position of these mirrors shifted, so did the shapes of the anemones.

t I

?I I

I \\ I.-

0 I

. - I4 /

ANeMONE I

-t

A NE MONE I1

unheard-of kind; the days of samplingand digital simulacra of acoustic instru-

ments still lay ahead. The "strangeness"of Xenakis's electroacoustic pieces often

surprised listeners; after the perfor-mances of Bohorat the 1968 Festival in

Paris [51], the critics described this work

as a "sonic cataclysm" [52] or as an ex-

ample of Xenakis's supreme ability to

transform known sounds into something

entirely unrecognizable [53]. In the

Polytope de Cluny, he was again reachingbeyond the ordinary. Drawing from his

experience with spatialized compositionssuch as Terretetorh1965-1966) and No-

mos Gamma 1967-1968), Xenakis used

multiple loudspeakers interspersed

throughout the audience for the spatial

projection of the seven layers of sound

[54]. The geometry of the performance

space did not allow for the creation of

circular patterns, but limited them to

variations of Ts and squares. Nonethe-

less, it impressed Pascal Dusapin to such

a degree that he recallshis experience of

attending the Polytopede Clunyas the "de-cisive shock" that inspired him to be-

come a composer [55].Xenakis continued to dream on a cos-

mic scale: he planned to celebrate the

American bicentennial with a gigantic

sound-and-light display connecting the

continents, then he envisioned a North-

ern Lights spectacle illuminating the

Earth's atmosphere above Europe and

North America [56]. in the latter

project, it was feared the planned use of

electromagnetic beams would harm the

ozonelayer

[57]. Thesegrandioseschemes were abandoned; another un-

usual idea to "illuminatethe dark side of

the new moon" with beams of light con-

centrated like a laser met the same fate

[58]. Xenakis's project for the openingof the Georges Pompidou Center for the

Arts in Paris (1978) was similarly ambi-

tious: it was to be a monumental laser

show accompanied by the music of in-

dustrial sirens. The whole population of

the citywould be subjected to the artistic

extravaganza,with no freedom of choice

for those not interested in the vagariesof

modern art. In the end, the artwork andthe public found a much more modest

site: a vinyl tent-pavilion temporarilyerected on the Beaubourg Plaza.

Xenakis called the multimedia installa-

tion he created there LeDiatope 59].

LEDIATOPE, 978

The change of prefix from "poly-" to

"dia-" across, through) indicated a shift

in emphasis from the coexistence of a

60 Harley, Music of Sound and Light: Xenakis's Polytopes

5/14/2018 Music of Sound and Light - slidepdf.com

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/music-of-sound-and-light 8/12

multitude of different spaces/objects/

phenomena to the homogeneous, envel-

oping spatialityof three media permeat-

ing each other: static architecture, mo-

bile sounds and equally mobile lights[60]. Xenakis, who designed both the

audiovisual spectacle and the soft vinyl

pavilion housing it, unified the elements

of light, music and spatial geometry in

this work (Fig. 6). In the dark interior of

the pavilion, a network of steel cables

supported 1,680 strobe lights. Four laserbeams were split by enormous prismsand reflected in 400 mirrors, shining off

the glass columns and floor. The con-

figurations of lights had a greater com-

plexity and refinement of movement

than in the previous projects, but the

basic geometric elements of points and

lines remained the same.

Nonetheless, the spectacle featured a

new element: an array of literary texts

suggesting the existence of a narrative.

In the program book, Xenakis included

quotations from five texts: (1) the "Leg-end of Er" from Plato's Republic, (2) a

segment of a creation myth from her-

metic writings attributed to the legend-

ary alchemist Hermes Trismegistus, (3)a reflection on infinity from Blaise

Pascal's Thoughts,(4) an apocalyptic vi-

sion from a novel byJean-Paul Richter

and (5) a popular description of the su-

pernova by astrophysicist Robert P.

Kirschner [61]. Stating that "it is diffi-

cult and not necessary to explicate a

spectacle of music at all levels,"the com-

poser chose texts that formed "multipleresonances" with each other and ex-

tended thematic threads from ancient

Greek culture to modern astronomy and

philosophy [62].All the texts contain cosmic-and at

times apocalyptic-imagery, with manyreferences to astounding patterns of

light. In the quotation from Plato, the

Greek soldier Er, killed in battle, sees

souls ascending a luminous pillar that

shines "like a bright rainbow."This is the

axis of the universe, binding togetherthe wheels of the cosmos. After listeningto the music of the spheres and forget-

tingabout their

past,the souls "like

shooting starswere all swept suddenly upand away to be born." In the excerptfrom Hermes Trismegistus, a medieval

alchemist dreams about a visit "from a

Being of vast and boundless magnitude"

basking in a "serene and joyous light."This is the mind of the Deity,which cre-

ates Life and Light and the Word of God,"the voice of the light." The alchemist

perceives divine secrets and understands

that through their twofold nature-mor-

Fig. 6. Xenakis,sketch of the pavil-ion constructed for

the performance of

LeDiatope, pub-lished in the pro- ~~

gram book for the -

installation (1978).

tal in body, immortal in mind-human

beings share in the perfection of the di-

vine mind. Pascal contemplates "the

sun's blazing light set like an eternal

lamp" in a universe that, by its sheer

scope, reduces human beings to total in-

significance. In Richter's apocalypticscene, the universe is empty: the

Godhead cannot be found in the Milky

Way,amidst a billion suns. The awe-in-

spiring grandeur of the universe incites a

feeling of terror in people observingthemselves suspended "between the two

abyssesof infinity and nothingness" (Pas-

cal) [63]. The tragic awareness of hu-

man solitude underlies the final excerptfor LeDiatope,a factual description of the

eruption of a supernova with a bright-ness "a billion times the luminosity of

the sun" [64]. The expanding starwould

engulf the whole solar system, destroyinghumankind in the process.

We can interpret the program of Le

Diatopeas a

testimonyto Xenakis's athe-

ism and his vision of human destiny as a

tragic solitude in the enormous, hostile

and empty universe. According to this

reading, ours is a world of chaos and vio-

lence that should be bemoaned and

feared. The texts lead the reader from

ancient beliefs in after-deathpunishmentand rewardthrough the revelation of an

androcentric, rationalisticuniverse to the

rejection of faith and abandonment of all

hope in salvation. The final descriptionof the supernova would then imply that

the infinity and destiny of the universe

may be,in the

end,understood and

pre-dicted only by science-the ultimate

source of human knowledge. This sce-

nario replaces religion with scientism and

faith in the revelatoryfunction of art.

The glorification of technology is evi-

dent in the composer's description of

the arrayof technical means used to cre-

ate the mobile configurations of pointsand lines [65]. The light patterns cre-

ated by the laser beams and flashes rap-

idly shifted and evolved. As in the

\) ,tq7i-7- r

Polytopede Cluny,the laser beams were

reflected in 400 special mirrors

equipped with optic filters and prisms.Mathematical functions-operations on

complex numbers and the calculus of

probabilities-controlled their continu-

ous and discontinuous motion. The use

of the rudimentary visual material of

points and lines of light invites compari-son with basic elements of the physicaluniverse: grains of matter and lines of

photon rays.In an analogy with the black

void of the empty Universe in which par-ticles of matter and light are scattered,the interior of the pavilion provided a

black background for the luminous con-

figurations. The pavilion itself was struc-

tured from several intersecting concave

and convex surfaces that Xenakis com-

bined to maximize the empty space and

minimize the covering surface.

Thus, with the assistance of powerful

technology, Xenakis created a new form

of audiovisual art, an abstractspectacleof "visualmusic" that portrayed, on a re-

duced scale, "the galaxies, the stars and

their transformation with the help of

concepts and procedures stemmingfrom musical composition." The most

important mathematical function in Le

Diatopewas,according to Xenakis, the lo-

gisticdistribution e applied to create the

musical form, rhythmic transformations,

complex timbres and the variable

streams of pitch-and-intensity patternshe called tressesrhythmiques rhythmicstrands) [66]. The same distributional

function was used in the creation of the

light patterns, evoking trajectories of

galaxies, violent storms, volcanic erup-tions, the aurora borealis, rotating or

dispersing spirals, and other mobile

configurations.Xenakis's creative power of imagina-

tion benefited from advanced technol-

ogy: all the events of the spectacle were

computer-controlled, requiring 140.5

million orders (binary commands) for

the 46 minutes of LeDiatope.As with the

Harley,Music of Sound and Light: Xenakis's Polytopes 61

5/14/2018 Music of Sound and Light - slidepdf.com

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/music-of-sound-and-light 9/12

Polytope eCluny, he control signalswere

registered on a multitrack magnetic

tape (realized at CEMAMu) also con-

taining the seven audio tracks of the

electroacoustic part of the spectacle en-

titled, after Plato's text, La LegendedEer

(realized in 1977 at CEMAMuand the

Elektronische Musikstudio of the

Westdeutscher Rundfunk in Cologne).In the legend, Plato described the fa-

mous music of the spheres as sung by si-

rens who were located on different or-bits of rotation. Each siren performedone pitch continuously and together

they sung the whole eight-note scale.

The cosmic revolutions described in this

legend are reflected in Xenakis's music

by the gradual transformation of super-

imposed layers of sound, the rotation of

sound masses [67] in audible circles and

spirals and the continuous modulation

of unusual timbres. The texts chosen bythe composer for the program book viv-

idly suggest the apocalyptic soundscapesof his music: "eternity resting on chaos

... the dissonances [that] gnashed with

even more violence . . . [before the

sound of] the interminable hammer of

bells" (Richter) or "adownward spiral-

ling darkness, terrible and grim, like a

serpent . . . making an indescribable

sound of lamentation ... an inarticulate

cry" (Trismegistus). Xenakis's appropri-

ately chaotic and dissonant music in-

cludes three families of sonorities: (1)instrumental sound (mostly from non-

European instruments), (2) pre-re-corded non-instrumental sound mate-

rial and (3) synthetic sound (realizedwith probability functions). The expres-sive power and vast dimensions of this

electroacoustic work surpassed all of

Xenakis's previous attempts to portray

huge volumes and masses of sound in

motion (such as his 1962 electroacoustic

composition Bohor). At the site of Le

Diatope, La Legended'Eerwas projectedfrom 11 loudspeaker systems surround-

ing the audience; other versions of the

music (a four-tracktape for concert per-formances [1977] and a stereo version

recorded on CD [1995]) allow for per-

formances at different venues.Nouritza Matossian expresses her ad-

miration of the technological marvels of

LeDiatope n her book Xenakis 68]. She

emphasizes the fierce beauty of this

spectacle, which evoked the power of

the physical world filtered through the

lens of mathematics. Jose Maceda, how-

ever, a Filipino ethnomusicologist and

composer, did not share her enthusi-

asm. Writing for a volume of studies de-

voted to Xenakis, Maceda offers a word

of caution, stating that Xenakis, by usingthe equipment of advanced technology,

justified a "technological and machin-

istic wayof life" [69]. It is not difficult to

see the roots of his argument in the eco-

nomic contrast between the First and

the Third World.

The Polytope eMycenes,imilarin many

ways to Persepolis but different in

sociopolitical context, was marked by a

peculiar coexistence of the archaic (an-

cient Greek culture) with the modern(new technologies). Xenakis designedthis work-or rather,festival-for the ru-

ins of the ancient Acropolis of Mycenae,

attempting to capture the pagan atmo-

sphere of the historic site in a monumen-

tal celebration [70]. Flashes of 12 anti-

aircraft searchlights and colorful

fireworks illuminated the whole regionwhile processions of children with

torches, herds of goats bearing lights and

bells, fires on the hilltops and other ef-

fects, such as projections of images of the

funeral masksof the Achaean kings onto

the stone wallsof the palace, contributedto the visual strata of this polytope. The

sound included recitations from Homer

and from recently discovered Myceneanfuneral inscriptions. The music included

performances of a series of Xenakis's

"Greek"compositions (A Helene,Oedipusa Colonne,Psappha,Persephassa,Oresteia)linked with seven electronic interludes.

These consisted of repetitions of a brief

piece, MycenaeAlpha,which was the first

composition realized entirely on the

UPIC, a computer system created at

CEMAMu hatsynthesizes

sounds on the

basis of designs drawn onto an electro-

magnetic table (Fig. 7).When he returned to the homeland

he had been forced to leave more than

30 years earlier, Xenakis took a pilgrim-

age to the ruins of what has been called

the cradle of Western civilization. There

the composer honored his cultural heri-

tage by presenting a series of musical

works inspired by such classic play-

wrights as Sophocles, Euripides and

Aeschylus. The scenes from the Oresteia,a trilogy on the curse-ridden dynasty of

the Achaean kings that inspired the fi-nal segment of the polytope, were par-

ticularly poignant near the tomb of

Agamemnon. Their expressive powerwas augmented by the outdoor acous-

tics. According to Christine Prost, one of

the choral conductors at the Polytopede

MycMnes,his music needed to be sungwith "guttural, closed and solid voices,voices of wind and sun" [71]-simple,

rough vocal timbres that would carrywell in the nocturnal darkness. Such a

performance required much greater ef-

fort from the professional singers in the

chorus than it did from the untrained

Greek women and children of Argoliswho also participated in the musical fes-

tivities. The latter group formed a sepa-rate choir, chanting archaic invocations

while descending in a slow processionfrom the mountains [72].

This site-specific polytope featured

abundant allusions to ancient Greek cul-

ture, but it excluded the thousands ofyears of Christiantradition in Greece. In

a leap back in time, Xenakis exploredthe dark and even sinister moments of

the archaic collective psyche as portrayedin the tragedies of Oedipus, Agamem-non, Helen of Troy and the curse of the

Atrides. But while these storiesdepict the

cruelty of fate and the omnipresence of

death, the atmosphere at the perfor-mances was not woeful. The spectaclewas, simultaneously, "a vast retrospectiveof Xenakis's music" and "agrand popu-lar celebration of democracy and free-

dom" [73] that gathered together over10,000 listeners for its five nightly perfor-mances (1-5 September 1978). The audi-

ence included tourists and international

music critics, but the majority of the

spectators came from the neighboring

valleys and villages. Conducted as a cel-

ebration of community spirit and na-

tional pride, the Polytopede Myceneswas

also attended by various state officials.

The music, though difficult for the unini-

tiated, was greeted with awe and admira-

tion. Xenakis's harsh sonorities were per-ceived as

appropriatefor austere rituals

and ancient subject matter [74].The coordination of the various

events, which were dispersed on several

hilltops around Mycenae, was not an

easy task, and Xenakis conducted the

proceedings with a walkie-talkiein hand

[75]. He gave cues for the setting of

fires, the commencement of marching

processions, the beginning of each

piece of music, the movement of the

shifting searchlights and the various

other elements of the spectacle [76].Three anti-aircraft searchlights located

at a distance of 10 kilometers fromMycenae were positioned so that their

bright beams formed a pyramid above

the ancient ruins. Other lights searched

the darkened sky,and there were distant

patterns of light descending from the

hilltops, creating the impression that

new stellar constellations had moved

down to Earth [77]. But these appar-

ently cosmic lights were actually carried

by a procession of schoolchildren and

goats. The enormous scope of this work

62 Harley,Music of Sound and Light: Xenakis's Polytopes

5/14/2018 Music of Sound and Light - slidepdf.com

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/music-of-sound-and-light 10/12

Alpha. The horizontal axis is time; the vertical axis is pitch. The hand-written score was de-

signed on the UPIC, a sound-design and synthesis unit created at CEMAMu. The aural re-

sult is one of the noise of shifting bandwidth and register.

} = __

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~3lr

sult is one of the noise of shifting bandwidth and register.

and its close connection to the land-

scape of the historic site led one critic,Dominic Gill from the Financial Times

[78], to call the polytope a new form of

art: "artg6ographique."Ten years later, Xenakis attempted to

repeat the success of PolytopedeMycenesand to reach out to the traditions of thearchaic culture of Crete in another

sound-and-light spectacle that pre-miered on 13 July 1987 at the ancient

Roman amphitheater in Aries. This ex-

travagantevent was entitled Taurimachie,

the title refers to the spectacle's main

protagonists: live bulls and horses. The

spectacle received bad press reviews [79]and may be described as Xenakis's singledramatic failure. Its lack of success seems

to have resulted from Xenakis's inabilityto take into account the reality of animal

life. He imagined stochastic patterns of

animals running wildlyaround the arena

amidst complex light patterns created by

rotating spotlights. The sonorous layerof this performance consisted of works

for percussion (Psappha and Pleiades),and a new piece for electroacoustic tapeand live computer-generated sounds

based on transformed samples of sounds

of actual bulls: Tauriphanie, hich was re-

alized on the UPIC. Not surprisingly, he

animals were frightened by the noise

and the blinding lights. Most of the time,instead of running around with excite-

ment, presenting livingicons of

primalsavagery, the bulls and horses huddled

together in dark corners near the

arena's walls, sheltering themselves from

unknown dangers.

CONCLUSION

Vast audiovisual spectacles have a long

history that ranges from Handel's royalfireworks to Scriabin's Prometheusand

the lasers of the popular rock group

Pink Floyd. But while this genre is

hardlya novelty, the work of Xenakis dif-

fers from that of his predecessors and

contemporaries by placing an emphasison the use of the most advanced tech-

nology to create abstract imagery for a

new form of modernist art. Nonetheless,

the dismantling of the Philips Pavilion,the Polytopede Montreal, the Polytopede

Cluny and Le Diatope highlights the

ephemeral nature of such large-scale

avant-garde artistic projects. One could

say that their continuous display is sim-

ply too costly, but their disappearance is

due to other reasons as well. Because

these projects explore the aesthetic po-tential of new technologies, their new-

ness is one of their main attractions. An

artistic object placed at the cutting edgeof time cannot simultaneously be a time-

less masterpiece: transient in essence, it

exists to dazzle with technological po-tential and then give way to more tech-

nically advanced art.

Xenakis's gigantic projects, which

Michel Ragon has called "spatial uto-

pias" [80], require the mobilization of

vast financial, human and material re-

sources. Such reserves are readily avail-

able in few places-among them, huge

corporations, rich governmental agen-cies and totalitarianmilitary institutions.

Xenakis was an early believer in the

"peace dividend," dreaming about the

artistic benefits ofconverting militaryequipment to peaceful purposes. As he

observed in Musique.Architecture,f the

use of armed forces were replaced with

non-repressive policies it would free the

resources and "l'art pourra survoler la

planete et s'elancer dans le cosmos"

[81]. He successfully initiated this con-

version with the polytopes, some of

which required military assistance (e.g.

searchlights, troops, transportation) and

depended on the resources and the cen-

tralized power of an essentially war-ori-

ented institution.

Xenakis's biographer, Matossian, at-

tributes the main inspiration for the

polytopes to Xenakis's war-time experi-ences [82]. She writes, "during his last

days as a partisan he watched from a

rooftop of the city as the R.A.F bombed

a German airport, fascinated and aghastat the superb light and sound show tragi-

cally using Athens for its stage."This text

is illustrated with an official war photo,issued by the BritishMinistryof Informa-

tion and depicting a Grecian night skywith trajectories of moving searchlightsand explosions of artilleryfire (lines and

points). The photograph, taken in May1941, comes from the collection of the

Imperial War Museum [83].The polytopes embody the artistic

praxis of Xenakis's favorite new science,

general morphology, which searches for

invariants and transformations of basic

forms and patterns [84]. These are

found primarilyin the inorganic natural

world as studied by astronomers, geolo-

gists and physicists, but they have also

been consciously used by creative artists-

scientists. For Xenakis, the work of the

artist is technical, experimental, ratio-

nal, inferential, intuitive, founded in in-

dividual talent and revelatory in nature

[85]. With its unique mode of knowing

through "immediate revelation," art cre-

ates a rich and vast synthesis that can

support and guide other sciences, ac-

cording to Xenakis.

The vast scale of the polytopes calls

for substantialsociopolitical support:they require funds and resources from

various organizations and need the pub-lic to visit them and care about them so

that the governments or other institu-

tions feel that their expenditures arejus-tified. As MargaretAtwood writes, there

are two factors in the production of a

"greatart"-the artist and the audience:

Takeaway he artist and the audiencecan never achieveself-knowledge....But take awaythe audience, and theartisthas partof himself cut off. He isblocked, he is like a man shouting tono one [86].

The Polytope de Mycenes providedXenakis with a nurturing audience. At

the revered site, amidst cyclopic walls

and monumental tombs, Xenakis

reached back to ancient Greek historyand created a festival of his own home-

coming. At Persepolis, he designed a

very similar spectacle drawing from the

cultural heritage of another ancient cul-

ture. Yet, the reception of this work was

Harley,Music of Sound and Light: Xenakis's Polytopes 63

5/14/2018 Music of Sound and Light - slidepdf.com

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/music-of-sound-and-light 11/12

different because of the political con-

text: there, Xenakis participated in cel-

ebrating the 2,500th anniversary of the

founding of the Persian empire, which

was destined to fall just 8 years later.

Persepolis, a grand work of Western ex-

perimental art based on themes relatingto Zoroastrianism and non-Islamic Per-

sian culture, did not have a proper pub-lic in the impoverished Iran. The con-

trast in the reception of two analogous

polytopes highlights the limitations ofmodern art's claims to universality. In

the 1960s, Xenakis's project for a cosmic

city articulated his belief in the utopia of

a borderless State of the Earth, replacingall the national states with a global politi-cal organization. With the polytopes,new art seemed to have become a trulyinternational enterprise: new inventions

and aesthetic trends were dispersed to

the ends of the world; citizens of all

countries had a chance to participate in

this art for all. Cultural differences

seemed to have become less important

than ubiquitous technology, inventionand progress. Perhaps it has returned

with the cult of the Internet, which intro-

duces a new image of the globe as cov-

ered by nets and webs. This is much dif-

ferent from the vision presented byXenakis's polytopes, which reached out

toward galaxies and interstellar voids.

Nonetheless, it carries on the promise of

a global multimedia art form.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to lannis Xenakis and Radu Stan

(Editions Salabert, Paris) for

making

available to

me the archival material held at Xenakis's studio:sketches and notes for Xenakis's polytopes (includ-

ing maps, diagrams on graph paper, transparencies,etc.) and for the Philips Pavilion, and programbooks of the Diatope, Shiraz festivals, Persepolis. Ithank Radu Stan for providing me with copies ofXenakis's scores and promotional recordings of his

music, including the Polytope de Montreal, Persepolis,

Polytope eClunyand other works.Bengt Hanmbraeusof McGill University was also helpful by providingaccess to sources such as the Program Book of thePoemeelectroniquef 1958, as well as early issues ofGravesaner Blitter.

References and Notes

1. Excerpt from Jean-Paul Richter's Siebenkas,

quoted in Xenakis's program for LeDiatope(Paris:

Centre Georges Pompidou, 1979); translated byJames Harley for the program of "ConcertXenakis"

(Montreal: McGill Univ., 15 April 1993).

2. lannis Xenakis, Formalized Music: Thought and

Mathematics in Composition (Bloomington, IN, and

London: Indiana Univ. Press, 1971) p. 144; for ref-erences to human intelligence see Xenakis,"Variete," Musique. Architecture (Tournai, Belgium:

Casterman, 1971; Rev.Ed., 1976), reprinted in Wil-liam B. Christ and Richard P. Delone, eds., TheArt

of Music: Tradition and Change (Bloomington, IN:

Indiana Univ. Press, 1973) and included (revisedversion) in the preliminary statement to Xenakis,Art-Sciences: Alloys, Sharon Kanach, trans. (New

York:Pendragon Press, 1985) p. 2. Originally pub-lished as Arts/Sciences. Alliages (Paris: Casterman,

1979).

3. This expression is quoted from Xenakis, "Laville

cosmique," in Musique. Architecture [2] p. 159.

4. For the origin of the term "polytope,"see PieterHendrik Schotte, Mehrdimensionale Geometrie,Vol. 2:

Die Polytope(Leipzig: G. J. G6schen, 1902-1905),which discusses hyperspace and concepts of linearand nonlinear space. For studies of the polytopes,see Olivier Revault d'Allonnes, ed., Xenakis/Les

Polytopes Paris: Balland, 1975). See also Maurice

Fleuret, "II teatro di Xenakis," in Enzo Restagno,ed., Xenakis (Torino, Italy: Edizioni di Torino,

1988) pp. 159ff, and a paper by Philipp Oswalt,"Polytope von Jannis Xenakis," 107Arch+(March1991) pp. 50-54.

5. Balint Andras Varga, Conversations with Iannis

Xenakis(London: Faber and Faber, 1996) p. 112.

(Originally published in Hungarian in 1980 and

1989.)

6. Varga [5] p. 112.

7. The history of the Philips Pavilion is well de-scribed in secondary literature about both Vareseand Xenakis. See Michel Ragon, "Xenakis

architecte," in Maurice Fleuret, ed., Regardssurlannis Xenakis (Paris: Stock, 1981) pp. 30-36;Nouritza Matossian, Xenakis(Paris: Fayard, 1981),also available in an English translation (London:Kahn & Averill, 1986); Ann Stimson, "The Scriptfor Poeme electronique: Traces from a Pioneer" Pro-

ceedings of the International Computer Music Conference

(Montreal: ICMA, 1991) pp. 308-310. Xenakis'stexts on the topic include "Le Pavilion Philips a

l'aube d'une architecture," Gravesaner litterNo. 9

(1957), reprinted in Musique. Architecture [2] pp.

123-142, and in Formalized Music [2].

8. Although Le Corbusier was the author of the

project, including its title, Xenakis designed thePavilion. However, the senior artist initially did not

give him credit for this work and claimed to haveauthored both the architecture and the display.Xenakis wrote about designing the structure of the

pavilion in Le Corbusier, Le Poeme electronique Le

Corbusier, ean Petit, ed., program book (Paris:Editions de Minuit, 1958) and in GravesanerBldtter

[7]. The battle for the authorship of the architec-ture of the Pavilion is described in Matossian [7].

9. Fleuret [4] pp. 174.

10. Xenakis, Musique. Architecture [2] pp. 123-126.

11. Stimson [7] pp. 308-310.

12. Quoted from Le Corbusier's mosaic of poetic-philosophical statements, included in the programbook [8].

13. Le Corbusier [12].

14. Xenakis, "Reflektioner 6ver Geste Elec-

tronique," Nutida Musik (Stockholm: March 1958)(in Swedish translation). Also published as "Notessur un 'geste electronique,"' in Revue musicaleNo.

244 (Paris, 1959) pp. 25-30 and reprinted in

Musique. Architecture [2] pp. 142-150. Notice that

Xenakis's term closely resembles Le Corbusier's

"jeuxelectroniques."

15. Xenakis, Musique. Architecture [2] p. 146.

16. Pierre Schaeffer, A la recherche d'une musiqueconcrete Paris: Editions du Seuil, 1952). See alsoCarlos Palombini, "Machine Songs V: PierreSchaeffer-From Research into Noises to Experi-mental Music," Computer MusicJournal 17, No. 3,14-19 (Fall 1993); and Jacques Poullin, "MusiqueConcrete," in Fritz Winckel, ed., KlangstrukturderMusik. Neue Erkentnisse Musik-elektronischerForschung,

(Berlin:Verlagfur Radio-Foto-KinotechnikGMBH)

pp. 109-132.

17. Annette Vande Gorne, "Espace/Temps:Historique,"in L'Espace u SonII, FrancisDhomont,

ed., special issue of Lien. Revue d'Esthetique Musicale

(1988) pp. 8-15; see also Carlos Palombini, "Ma-chine Songs V: Pierre Schaeffer-From Researchinto Noises to Experimental Music,"ComputerMusic

Journal17, No. 3, 14-19 (1993).

18. See Gyorgy Ligeti, "Metamorphoses of Musical

Form," and Mauricio Kagel, "Translation-Rota-

tion," in DieReihe,No. 7 (1960 [German Ed.], 1965

[English Ed.]). See also George Rochberg, "TheNew Image of Music," Perspectives of New Music 2,

No. 1, 1-10 (1963); and Karlheinz Stockhausen,"Musik m Raum,"Die Reihe,No. 5 (1959 [German

Ed.], 1961 [English Ed.]). Also published in

Stockhausen, Textezur Elektronische und Instrumental

Musik, Bd. 1 1952-1962 (Cologne: Verlag M.DuMont Schanberg, 1963).

19. Wassily Kandinsky, Point and Line to Plane

(1913); included in WassilyKandinsky, Kandinsky:Complete Writings on Art, Kenneth C. Lindsay and

Peter Vergo, eds. (Boston, MA: G.K.Hall, 1982).

20. EXPO 67 lasted from 28 April until 27 October1967. When it was over, the French Pavilion-oneof the few buildings spared demolition-became acenter for Franco-Quebecois culture. It continuedto house various exhibitions (most notably as a Mu-seum of Civilization) and to display Xenakis's

polytope until its conversion into a casino in 1994.

21. Terre des hommes/Man and His World, EXPO 67

program (Ottawa: Canadian Corporation for the1967 World Exposition, 1967).

22. Gabrielle Roy, "The Theme Unfolded byGabrielle Roy," in Terre des hommes/Man and His

World21] p. 21.

23. According to Xenakis's notes for this project,preserved in his studio and reproduced byd'Allonnes in Xenakis/Les Polytopes [4] pp. 65-69. See

also Xenakis, Musique. Architecture [2] pp. 171-173;

Matossian [7] pp. 214-216; and Varga [5] p. 114.

24. Xenakis quoted in d'Allones [4] p. 63.

25. Maryvonne Kendergi, "Xenakis et les

Quebecois," in Fleuret, ed. [7] p. 301-314.

26. Micheline Coulombe-Saint Marcoux, inter-viewed in Kendergi [25] p. 304.

27. Fleuret [4] pp. 159-187.

28. Xenakis, Formalized Music [2] p. 179.

29. Under the autocratic rule of Shah MohammedReza Pahlavi, Iran set off on a path towardmodern-ization and Westernization. From the time of hisexile in 1963, Ayatollah Khomeini denounced theShah's financial extravagance and his suppressionof both Islamic traditions and political dissent. The

Persepolis celebrations, during which the Shahswore faithfulness to the values of pre-Islamic Iran,were the Ayatollah's prime target. See MohammedReza Pahlavi, The White Revolution of Iran (Teheran:

Imperial Pahlavi Library, 1967) and Said Amir

Arjomand, The Turban for the Crown: The Islamic

Revolution in Iran (New York and Oxford: Oxford

Univ. Press, 1988).

30. Chester G. Starr, A History of the Ancient World,4th Ed. (New Yorkand Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press,

1991) pp. 277-281.

31. The Shiraz festivities have been described inmany books on Iran's recent history. Positive ac-

counts can be found in Pahlavi [29] and in Minou

Reeves, Behind the Peacock Throne (London: Sidgwickand Jackson, 1986). Criticism appears in Marvin

Zonis, Majestic Failure: The Fall of the Shah (Chicago,

IL,and London: Univ. of ChicagoPress,1991) and inAmir Taheri, The Unknown Life of the Shah (Londonand Sydney:Hutchinson, 1991). According to the lat-

ter, the Shah identified himself as a "newCyrusdes-

tined to revive Iran's ancient grandeur," and this

grandeurwas the focus at Persepolis (p. 193).

32. Marvin Zonis, Majestic Failure: The Fall of the Shah

(Chicago, IL: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1991); Minou

64 Harley,Music of Sound and Light: Xenakis's Polytopes

5/14/2018 Music of Sound and Light - slidepdf.com

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/music-of-sound-and-light 12/12

Reeves, Behind he PeacockThrone London: SidgwickandJackson, 1986).

33. Jalal Al-i Ahmad, Occidentosis:A Plague rom the

West,R. Campbell, trans. (Berkeley, CA: Mizan

Press, 1984; first publication in 1964). An"occidentotic" person is someone who has studiedin the West and been uprooted from his or her cul-

ture; one of the symptoms of occidentosis is "themelancholia of glorying in the nation's remote

past" (p. 134).

34. Zonis [32].

35. For the realization of Persepolis,Xenakis had athis disposal all the technical resources of IranianTelevision.

Accordingto Maurice

Fleuret,the same

institution was later one of the sponsors of the to-

tally automated Polytope eCluny.See Fleuret, "Une

Musique a voir," L'Arc,special issue on Xenakis

(Paris: 1972) pp. 32-36.

36. Undated diagram preserved in Xenakis's ar-chives among source materials for the compositionEchange 1989).

37. Xenakis's notes forPolytopedePersepolisrom hisarchives. See also Fleuret [4] p. 177; Matossian [7]

pp. 217-218; Revault d'Allonnes [4].

38. Fleuret [4] p. 182.

39. This is the account given by Fleuret in Maurice

Fleuret, "Bilan et lecon des journees de musiquecontemporaine," La RevueMusicale,Nos. 265/266

(1969) pp. 7-13. This special double issue is de-

voted to Varese, Xenakis, Berio and Pierre Henry,four composers who were featured at the Days of

Contemporary Music, Paris, 25-31 October 1968.

40. Olivier Revault d'Allonnes, "Xenakis et la

modernite," L'Arc(1972) p. 26. Charles Gounod

(1818-1893) was a nineteenth-century conservativeFrench composer, author of numerous operas, in-

cluding Faust.About Gounod, TheNewDictionaryofMusic and Musicians states, "Because of his greatpopularity and stylistic influence on the next gen-eration of composers, he is perhaps the central fig-ure in French Music in the third quarter of the19th century."See Stanley Sadie, ed., TheNewDictio-

nary of Music and Musicians, Vol. 7 (London:Macmillan).

41. Varese-Xenakis-Berio-Pierre Henry. Oeuvres-

Etudes-Perspectives, special issue of La RevueMusi-cale

[39].42. Fleuret [39] p. 7.

43. For a positive account about the students' ac-

tions, see Barbara Ehrenreich and JohnEhrenreich, Long March, ShortSpring:The Student

Uprisingat Home and Abroad (New York and Lon-don: Monthly Review Press, 1969). Criticisms ap-pear, for instance, in Stephen Spender, "Notes onthe Sorbonne Revolution," in TheYearof the YoungRebels New York, Random, 1968-1969) pp. 37-38;Lewis S. Feuer, TheConflictof Generations:The Char-acterand Significance fStudentMovementsNew Yorkand London: Basic Books, 1969).

44. Fleuret [39] p. 10.

45. Fleuret [39] p. 9.

46. Fleuret [4] p. 178.

47. This description of the Polytope eCluny s basedon accounts given in d'Allones [4]; Fleuret andXenakis [37]; Matossian [7] pp. 218-222; andFleuret [4] p. 175.

48. Varga [5] pp. 115-116.

49. The account of the music is based on listeningto a promotional copy (cassette tape) provided byEditions Salabert, Paris (Xenakis's publisher).

50. Iannis Xenakis, CatalogueGeneral des Oeuvres,Radu Stan, ed. (Paris:Editions Salabert, 1992). List

of works with a biographical note, list of awards,

bibliography, discography, filmography.

51. Fleuret [39].

52. La Tribunede Lausanne, reprinted in La RevueMusicale[39] p. 167