Museums as Realms of (dis)Enchantment - Chapman University

Transcript of Museums as Realms of (dis)Enchantment - Chapman University

Chapman University Chapman University

Chapman University Digital Commons Chapman University Digital Commons

Art Faculty Articles and Research Art

2020

Museums as Realms of (dis)Enchantment Museums as Realms of (dis)Enchantment

Amy Buono

Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/art_articles

Part of the Latin American History Commons, Latin American Languages and Societies Commons,

Museum Studies Commons, and the Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons

Museums as Realms of (dis)Enchantment Museums as Realms of (dis)Enchantment

Comments Comments This article was originally published in Latin American and Latinx Visual Culture, volume 2, issue 2, in 2020. https://doi.org/10.1525/lavc.2020.220007

Copyright The Regents of the University of California

Museums as Realms of (dis)Enchantment

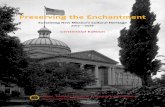

On the night of September , , a blaze swept throughBrazil’s national museum, Museu Nacional, in Rio deJaneiro, destroying not only the colonial building, portionsof which dated to the sixteenth century, but roughly percent of the million objects in its holdings. Thiswas Brazil’s greatest encyclopedic museum, incorporating(among many others) collections of natural history, anthro-pology, archaeology, and art, thus forming the most com-prehensive museum collection in the nation. Along withits many unique and irreplaceable collections, the MuseuNacional was also home to the country’s oldest IndigenousBrazilian and Afro-Brazilian materials (fig. ).

With origins in the nineteenth century, the museum de-veloped from the Portuguese Royal collections and librariesbrought to Rio in , after the court fled the Napoleonicinvasion of Portugal at the end of . Dom João VI do-nated the natural history specimens that constituted thecore collections of the museum when it was formally estab-lished in Rio as the Royal Museum in . The Museu Na-cional, as it was renamed, expanded over the next twocenturies through expeditions, donations, excavations, andstrategic acquisitions and exchanges. Thus, from the time ofits foundation, the Museu Nacional was not only one ofBrazil’s oldest and most venerable institutions but alsoamong the most central public establishments devoted toknowledge production in the biological and social sciences.The museum sits at some distance from the city’s more ex-clusive beach neighborhoods of Ipanema, Copacabana, andLeblon. Located in the northern São Cristóvão neighbor-hood, within the majestic (and now partially abandoned)Quinta da Boa Vista Park, theMuseu Nacional—along withthe park’s Zoological Gardens—has been a destinationpoint and memory marker since the late nineteenth century.Until the fire, schoolchildren and families strolling throughthe park and zoo, together with throngs of tourists fromacross Brazil and the world, visited the museum.

Perhaps less known to those outside Brazil, the MuseuNacional is also a part of the Federal University of Rio deJaneiro (UFRJ), a “museum-campus” that serves as a preem-inent institution for teaching and research. In , during

the Getúlio Vargas regime, the collection and their manage-ment became part of the university system. Budding andseasoned anthropologists, archaeologists, paleontologists,zoologists, botanists, linguists, and other specialists workwith objects and specimens, teaching, studying, researching,documenting, curating, and conserving. Integrated into thepublic university system, it has long served as a space wherestudents, staff and faculty worked on and in the presence ofmummies, meteorites, funerary urns, insects, paintings,sculpture, and featherwork, to name just a few of the muse-um’s myriad objects. The exhibition spaces of the museumwere physically and conceptually attached to offices, class-rooms, research labs, archives, and to Brazil’s oldest researchlibrary. Through its long history, the museum has been aliving point of connection between the historic and con-temporary spaces of Brazil, binding communities withinand well beyond Rio, from Amazonian and quilombola(Afro-descendant) communities to scholars, artists, and in-tellectuals from throughout the country and world.

The world watched in horror as the fire’s progress wasstreamed live on television. The overall list of materials lostis breathtaking. Among those that perished—and this isonly a token list—were innumerable holotype biologicalspecimens, fossils, dinosaur bones, Egyptian and Greco-Roman artifacts, pre-Columbian ceramics and textiles, fres-coes from Pompei, and the oldest human skeleton in theAmericas. The library included one of the largest collectionsof anthropological literature in Latin America. These lossesare appalling not only due to the vast numbers of thingsdestroyed and the uniqueness of so many individual items,which could be the case if any other museum suffered a sim-ilar catastrophe, but also because the destruction includedentire corpuses of material that existed nowhere else in theworld and therefore have vanished entirely.

Although only a small fraction of the millions of arti-facts destroyed in a single night, the loss of Brazil’s Indig-enous material culture is immeasurable, including uniquecollections of Brazilian featherwork, ceramics, and bas-ketry. Current estimates suggest that the fire destroyedover forty thousand artifacts related to Brazil’s Indigenous

Dialogues 79

Latin American and Latinx Visual Culture, Vol. , Number , pp. –. Electronic ISSN: - © by The Regents of the University of California.All rights reserved. Please direct all requests for permission to photocopy or reproduce article content through the University of California Press’s Reprints andPermissions web page, https://www.ucpress.edu/journals/reprints-permissions. DOI: https://doi.org/./lavc..

Dow

nloaded from http://online.ucpress.edu/lalvc/article-pdf/2/2/79/405309/lavc_2_2_079.pdf by guest on 16 July 2020

populations alone.1 In quantity, historical depth, scopeand range, this was a corpus of Brazilian Indigenous ma-terial and intangible heritage unequalled by any collectionsstill extant in the world.

It is also very important to recognize that the losses werenot only of the material objects but also field notes and con-textual materials, such as audio recordings of languages ei-ther no longer spoken or in decline. All of these materialswere of crucial importance for contemporary Indigenousgroups across Brazil, who used them to trace relationshipsto the past and to constitute memory. In a similar manner,theMuseuNacional’s Africana collections, as well as objectsproduced by Afro-descendants in Brazil, were particularly

significant: these were the oldest and best documented col-lections in Brazil, dating from the time of slavery and givingtestimony to everyday life, religious life, and histories of en-slavement and repression on a systemic level. While an un-known amount of related material survives elsewhere, it liespiecemeal in a variety of institutions across the country,some in hard to access police and legal medicine collections,others in more accessible state museums and university col-lections. The fragmentation of the collections makes theirpublic contemplation and scholarly study logistically andpractically problematic, if not impossible, to study.

As the largest and oldest collection of historical andcultural artifacts in Latin America, this extraordinary losshas global consequences for Indigenous rights, the historiesand collective memories of entire populations. It also ren-ders future scholarship that might have been based uponthese collections, including my own, now impossible. Likethe Africana materials, what does survive of the historicaland material record of Indigenous cultures of Brazil fromthe sixteenth through eighteenth centuries now exists onlyin fragmented and scattered form throughout archives,museums, and other institutional collections across the

FIGURE 1. Fire, Museu Nacional/ Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, September , . Photo by FelipeMilanez. Wikimedia Commons, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike . International license,commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fire_-_Museu_Nacional_.jpg (accessed March , ).

Special thanks Tatiana Flores and Harper Montgomery for creating aforum for this discussion, and to Flávia Nogueira de Sá, Roberto Conduru,and Wendy Salmond for valuable conversations on museums in peril.

. For losses, see Ana Lucia Araujo, “The Death of Brazil’s NationalMuseum,” American Historical Review , no. (April ): ; For ahistoric look at the catalogs of anthropological and ethnographic holdings ofthe National Museum, see Crenivaldo Regis Veloso Júnior, “Índice de objetos,índice de histórias: o catálogo geral das coleções de antropologia e etnografia doMuseu Nacional,” Ventilando Acervos, special issue, no. (September ):–.

80 LATIN AMERICAN AND LATINX VISUAL CULTURE

Dow

nloaded from http://online.ucpress.edu/lalvc/article-pdf/2/2/79/405309/lavc_2_2_079.pdf by guest on 16 July 2020

world, mostly in Europe. Long before modern-day museumtragedies, Brazil (like so many other nations in the GlobalSouth) had already been historically dispossessed of itsmaterial and intangible heritage through colonialism. As wehave now seen, what remains in domestic collections,whether in Museu Nacional or in countless other places inthe Global South, exists in perilous states of neglect or dis-repair from severe budget shortages.

TheMuseu Nacional had experienced drastic budget cutsin recent years that made its compliance with proper safetystandards impossible. As detailed in an April report bythe Federal Police in Brazil, an overheated air conditioningsystem was believed to be the cause of the fire.2 Because ofan inactive smoke detector system, malfunctioning sprin-klers, missing water hoses, open fire doors, and faulty secu-rity cameras, the inferno could not be contained. Thus,we know that the disaster was also completely preventable.The financial precariousness of the public sector in Riode Janeiro, with its budget cuts, delayed infrastructural im-provements, poor oversight, and general neglect, was ulti-mately the kindling upon which the blaze was ignited. Infact, although the Museu Nacional fire was certainly themost catastrophic in Brazil, it was by no means the first oronly such disaster. Brazil has witnessed multiple museumfires that signal consistent problems with both infrastructureand staff oversight, resulting in devastating effects for thecultural and scientific sector and its valorization in Brazil.Most notable for readers in the art world, no doubt, is thedevastating fire in Rio de Janeiro’s Museum ofModernArt (MAM), which destroyed percent of the famedmodernist collections. In , a fire broke out in one ofBrazil’s (and Latin America’s) most important biologicaland research centers, the Butantan Institute in São Paulo,destroying laboratories and the institute’s entire collectionof , snake specimens. In , a fire ravaged themuch-beloved Museum of the Portuguese Language, also inSão Paulo. These tragedies point to systemic negligence inthe public sector for the sustaining of scientific and culturalheritage. Private safeguarding of artistic works has proved justas insecure, as was seen in the fire in a private home inRio de Janeiro, where two thousand works by contemporaryBrazilian artist Hélio Oiticica (–) were destroyed.

The same financial and political tinder-by-neglect is re-peated in too many cities across Latin America and theGlobal South to name. The scale and dramatic nature ofthe losses at Museu Nacional highlight the importance ofsafeguarding ethnographic collections, which are not onlyof importance to historians, but also vital for writingabout modern and contemporary visual and material cul-ture in Latin America. As Latin American and LatinxVisual Culture readers, and as writers, art makers, curators,and cultural historians, we might do well to consider thatethnographic, historical, and archaeological collectionshelp give voice to diverse histories and give testimony todiverse artistic practices. As art historian Ruth Philips hasso poignantly stated: “Historical objects are witnesses,things that were there, then. They bear their makers’ marksin their weaves, textures and shapes, and have a compellingagency to cause people living in the present to enunciatetheir relationships to the past.”3

Within the United States, art museums are facing de-mands for reckoning in the wake of the opioid epidemic, the#MeToo movement, and the Trump presidency. Increas-ingly, the ethical stakes of museums and cultural heritagesites are being raised; their powers to display, educate, anddefine history are being challenged; and, in a closely relatedarea, the power of monuments and memorials to endorse orstage violence, as well as to assuage, heal, and embody grief,are being questioned. Museum publics are increasingly ask-ing institutions to face up to their fraught financial donorbase and colonialist legacies, hiring policies, and exhibitionand acquisition practices, the mechanics of which were forso long discreetly and deliberately hidden from view. Thecontext of these dilemmas is both long-standing and intrac-table: the Eurocentric, patrician roots of art history and itsfounding subjects, methods, and practitioners; the gutting ofpublic funding for the arts and humanities across the Amer-icas; and the power of the global contemporary art marketto construct canons. How do museums today begin to rec-oncile these legacies with their new realities—with intersec-tional identities, with social media, with the visual, material,and artistic worlds of local, global, and transnational com-munities? However important these ethical issues related tomuseums and the behavior of their donors and staff are—and I in no way dispute that importance—they are of a fun-damentally different order than the truly existential nature

. Fabio Serapião, “Curto em ar-condicionado causou fogo que destruiuMuseu Nacional, diz perícia” [Short-circuit in the air conditioner caused thefire that destroyed the National Museum, says criminal investigation],Estadão (São Paulo), March , , https://brasil.estadao.com.br/noticias/rio-de-janeiro,curto-em-ar-condicionado-causou-fogo-que-destruiu-museu-nacional-diz-pericia,.

. Ruth B. Phillips, “Re-placing Objects: Historical Practices for theSecond Museum Age,” Canadian Historical Review , no. (March ):.

Dialogues 81

Dow

nloaded from http://online.ucpress.edu/lalvc/article-pdf/2/2/79/405309/lavc_2_2_079.pdf by guest on 16 July 2020

of what has transpired in Brazil. Do not governments, econ-omies, and societies have an obligation to take the necessarysteps to ensure that the objects in these collections continueto exist?

Indeed, the very definition of what a museum is has nowbecome a source of confusion. Prior to the InternationalCouncil of Museums (ICOM) Twenty-fifth General As-sembly in Kyoto this past September , ICOM held that“A museum is a non-profit, permanent institution, . . .which acquires, conserves, researches, communicates and ex-hibits the tangible and intangible heritage of humanity andits environment for the purposes of education, study and en-joyment.” ICOM’s recently drafted new definition beganwith a declaration that museums are “democratizing, inclu-sive and polyphonic spaces for critical dialogue about thepast and future.”4 France was quick to critique the proposal,stating that the definition was too ideological, leading to aprolonged and unresolved debate which itself deserves richstudy. After hours of deliberation, a consensus of non-consensus led to a postponement in formally adoptingthe revised definition, with France winning the support of out of national and regional delegations, and nodate in sight for a revised definition or new vote. What issignificant, in the context of this essay, is that ICOM’s newmuseum definition, despite the jargon, was trying to em-phasize the significance and role of objects and collectionsthat lie in limbo outside dominant cultural patrimonies.This is the disenchanted realm—poorly funded and politi-cally marginalized—in which so many museums and re-search institutions of ethnology and culture in the GlobalSouth find themselves.

In a larger framework, cultural heritage disasters bringeven more questions to the surface in relation to museumsand international spaces of cultural display, because theyopen up the stage for large-scale reckoning about the role ofcultural sites for the modern nation-state. The fire thatripped through Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris in April received extraordinary international attention and ledimmediately to fundraising on a massive scale, no doubtspurred on by the iconic status of Notre-Dame de Paris notonly as a marker of French national identity but also as aninternational tourist site. In a Latin American context, theMuseu Nacional fire resulted in a near-total cultural loss onan almost unimaginable scale, including the archaeological,

ethnological, historical, biological, and artistic works, analo-gous to losing the Smithsonian Institution or the Metropol-itan Museum of Art. In contrast to Notre Dame, however,the Museu Nacional fire elicited a briefer and less impas-sioned international response, and vastly smaller philan-thropic impulses. These losses push the conversation fromone dominated by markets, values, canons, and identitypolitics—the issues swirling around US institutions—intothe terrain of cultural memory, the relevance of the past tothe present, and the construction of identities today. Fur-thermore, these collections help us both understand andquestion the very objects that we study and what we con-sider of cultural relevance. Rather than comparing whathappened in Rio to either Notre Dame or to the currenttravails of the Met, perhaps the proper analogy is to thelooming threat of species extinction writ large, also attribut-able to societal neglect. To push the analogy still further, theextinction of the entirety of the extant material and intangi-ble culture of many Indigenous populations of Brazil in asingle night changes, diminishes, and imperils the larger so-cial and cultural ecosystem. Officials at the Museu Nacionalare predicting that parts of the palace building will be recon-structed and reopened to the public in , in honor of thebicentenary of Brazilian Independence. Until then, portionsof the surviving archives and collections will be exhibited inRio and Brasilia, in part to raise private and public moniesand awareness for Museu Nacional’s future. The museum isalso collecting donations from around the world in its ef-forts to rebuild. Even those of us working and teaching inthe Global North should not be complacent about the dura-bility of our own institutions, or of our government’s role insupporting them. The financial, cultural, and political eco-systems that sustain museums are fragile and need our im-mediate attention.

Amy BuonoChapman University

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Amy Buono is assistant professor of art history at Chap-man University. Her interests include Indigenous and Afro-Brazilian artistic practices, material and intangible heritagestudies, and colonialism and ethnopolitics. She is authoringTupinambá Feathercraft in the Brazilian Atlantic (Universityof Pennsylvania Press), and coediting A Cultural History ofColor in the Renaissance (Bloomsbury Press).

. Vincent Noce, “Vote on Icom’s New Museum Definition Postponed,”Art Newspaper, September , , www.theartnewspaper.com/news/icom-kyoto.

82 LAT IN AMERICAN AND LATINX VISUAL CULTURE

Dow

nloaded from http://online.ucpress.edu/lalvc/article-pdf/2/2/79/405309/lavc_2_2_079.pdf by guest on 16 July 2020