Stoyanov (2009)_Trade Policy of a Free Trade Agreement in the Presence of Foreign Lobbying

Mukherjee and Suetrong (2012)_Trade Cost Reduction and Foreign Direct Investment

-

Upload

tan-jiunn-woei -

Category

Documents

-

view

213 -

download

1

Transcript of Mukherjee and Suetrong (2012)_Trade Cost Reduction and Foreign Direct Investment

-

Economic Modelling 29 (2012) 19381945

Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect

Economic Modelling

j ourna l homepage: www.e lsev ie r .com/ locate /ecmod

Trade cost reduction and foreign direct investment

Arijit Mukherjee a,b,, Kullapat Suetrong c

a University of York, UKb CESifo, Germanyc Department of Business Development, Ministry of Commerce, Thailand

We thank three anonymous referees, Wilfred J. EthMarjit, James R. Markusen and the participants at the Gthe University of Nottingham, UK, for helpful commenpresented here are solely of the authors and not necesusual disclaimer applies. Corresponding author at: Department of Economics

of York, Heslington, York, YO10 5DD, UK. Fax: +44 1904E-mail address: [email protected] (A. Muk1 See Markusen (2002) for an overview of the th

corporations.

0264-9993/$ see front matter 2012 Elsevier B.V. Alldoi:10.1016/j.econmod.2012.06.008

a b s t r a c t

a r t i c l e i n f oArticle history:Accepted 4 June 2012

JEL Classifications:F12F21F23L13L24

Keywords:ExportFDITrade cost

While the proximity-concentration theory suggests a positive relationship between trade cost and foreigndirect investment (FDI), there is ample evidence showing a negative relationship between them. We showthat the possibility of exporting back to the home country from a host country, which is often referred ashome-country export platform FDI, may generate a negative relationship between trade cost and FDI.Market demand and product market competition may play important roles in this respect.

2012 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

An important development in recent years is the growth of foreigndirect investment (FDI) (UNCTAD, 2006), which has created a largeliterature explaining the nature, causes and consequences of FDI.1

An important rationale for undertaking FDI is provided by the so-called proximity-concentration theory suggesting that trade costreduction reduces the incentive for FDI (see, Brainard, 1997).

Although trade costs are reduced in recent years, they remainprominent. In a survey, Anderson and Wincoop (2004) mentionthat Trade costs are large, even aside from trade-policy barriersand even between apparently highly integrated economies.Arough estimate of the tax equivalent of representative trade costsfor industrialized countries is 170 percent. This number breaksdown as follows: 21 percent transportation costs, 44 percentborder-related trade barriers, and 55 percent retail and wholesaledistribution costs The 44-percent border-related barrier is a

ier, Elhanan Helpman, SugataEP Trade costs conference atts and suggestions. The viewssarily of their institutions. The

and Related Studies, University323 759.herjee).eory of FDI and multinational

rights reserved.

combination of direct observation and inferred costs. Total interna-tional trade costs are then about 74 percent. The well-known grav-ity equation is used for a long time to show the effects of trade costson trade flows. However, it has been acknowledged in recent yearsthat, while focusing on trade between regions i and j, the gravityequation will look not only at the trade costs between these regionsbut also at the trade costs between regions i and j relative to thoseof the rest of the world and the economic size of the rest of theworld. Eaton and Kortum (2002), Anderson and Wincoop (2003),Feenstra (2004) and Baier and Bergstrand (2009) consider differentapproaches to estimate unbiased gravity equations showing the ef-fects of multilateral resistance for trade.

The prediction of the proximity-concentration hypothesis is intu-itive, yet empirical findings in the 1990s often counter this prediction.The worldwide boom in FDI during the 1990s coincides with dramaticfall in both technological and policy-induced trade costs. For example,on the one hand, UNCTAD (2004) reports Trade reforms in develop-ing countries over the past 10-to-15 years are reflected in the generaldecline in protection in these countries, often under World Bank/IMFprograms. Chinese import tariffs, for example, dropped from 34.8% to12.4% in year 1992 to 2001; Indian tariffs fell from 70.5% to 28.0% inyear 1990 to 2001. On the other hand, UNCTAD (2002) shows thatFDI inflows to China and India have increased respectively by almostdouble and four times between 1990 (annual average between 1990and 1995) and 2001.

Feinberg et al. (1998) found a negative relationship between tariffreduction and FDI by looking at the effects of USACanada tariff

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2012.06.008mailto:[email protected]://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2012.06.008http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/journal/02649993 -

1939A. Mukherjee, K. Suetrong / Economic Modelling 29 (2012) 19381945

reduction on the behaviour of the multinationals and their affiliates.In this respect, idiosyncratic firm characteristics such as technologiesplay important roles.

We use simple theoretical models to explain that, in contrast tothe proximity-concentration hypothesis, trade cost reduction may in-crease horizontal FDI. We consider that a foreign firm serves its homecountry and a host country either from its home plant or from a host-country plant. The diseconomies created by the plant-specific fixedcost2 may prevent the foreign firm from operating plants in bothcountries, thus creating the necessity for exporting back to thehome country if the foreign firm serves the markets from its hostcountry plant.3 Considering a monopolist producer, we show inSection 2 that lower trade cost may increase the foreign firm's incen-tive for FDI if the host-country market is larger than the home-country market and the host-country demand is more elastic thanthe home-country demand.4 However, demand asymmetry is notnecessary for explaining the negative relationship between tradecost and FDI. Assuming the same market size in the home and thehost countries, we show in Section 3 that a lower trade cost mayincrease the incentive for FDI in the presence of product marketcompetition, where the host country firm is very cost inefficientthan the foreign firm. Hence, market demand and relative cost effi-ciency of the foreign investor, which are often considered to be therelevant factors for FDI, may play important roles in determiningthe relation between trade cost and FDI. The possibility of exportingback to the home country of the foreign firm is the crucial factor forour result.

It has been argued that the host-country policies are facilitatinginvestments from abroad by reducing the costs of undertaking FDIs(Markusen and Venables, 1998). On the one hand, a lower tradecost tends to reduce FDI, and, on the other hand, a lower cost of un-dertaking FDI tends to increase FDI. On the balance, the incentivefor FDI may increase following the reduction in trade cost and thecost of undertaking FDI.5 Although host-country policies createmore congenial environment for investment, thus reducing thecosts of FDI, significant costs of FDI remain. These costs may arise sim-ply because the foreign firms need to set up their plants and distribu-tion channels in the host countries. There may also be significantamount of transaction costs related to FDI, which may arise due topoor infrastructural facilities and administrative barriers such ascorruption and policy discrepancy (Bhuiyan, 2003; Hines, 1995). Weshow that even if the cost of undertaking FDI is not affected, a lowertrade cost may increase the incentive for FDI in the presence ofhome-country export platform FDI.

There are few theoretical works showing that trade cost reductionbetween the home and the host countries can increase FDI. Smith(1987) shows that scale economies, which affect the entry decisionof a host-country firm, may be a reason for this type of relationship.6

Lommerud et al. (2003) highlight the role of the unionized labourmarket. While the former paper may be suitable for an infant host-country industry where intense competition from the foreign firmsprevents entry of the host-country firms, the latter paper shows the

2 See Horstmann and Markusen (1987) for an earlier work showing the effects offirm-specific and plant-specific fixed costs.

3 Exporting back to the home country from a host country plant is often referred ashome-country export platform FDI (Ekholm et al., 2007). As documented in Ekholmet al. (2007), in 2003, 60% of total sales of foreign affiliates of the USA multinationalswere sold domestically, while 40% were exported. Out of the latter figure, about a thirdwas exported back to the USA and about two thirds were exported to third countries.

4 We thank an anonymous referee for pointing out this aspect of the problem to us.5 There is a related literature which shows how investment liberalization policy,

which decides whether or not cross-border merger will be allowed, affects welfare(Norback and Persson, 2007).

6 Focusing on a specific market demand function, Motta (1992) extends this line ofresearch by introducing a cost of information acquisition by the multinational firm.

implication of input market imperfection. In contrast, we show theimplications of a new factor, viz., exporting back to the home countryof the foreign firm. In order to do so, we consider a given marketstructure and perfectly competitive input markets, thus assumingaway the factors responsible for the results in Smith (1987) andLommerud et al. (2003).7

Ethier and Markusen (1996) show that a non-monotonic relationbetween trade cost and FDI may occur if FDI reduces value of the mul-tinational firm's knowledge following defection by the host-countryfirms. On the one hand, higher trade cost makes FDI profitable, but,on the other hand, defection by the host-country firm reduces the in-centive for FDI. In contrast, there is no loss of the multinational firm'sknowledge in our analysis. Hence, defection by the host-country firm,which is the reason for creating the ambiguous effect of a trade costreduction on FDI in Ethier and Markusen (1996), is absent in ouranalysis.

In contrast to our paper, which shows the effects of a trade cost re-duction on horizontal FDI, Grossman and Helpman (1996) use amodel with political lobbying, where higher tariff encourages largerdonations from the domestic manufacturers, to show how FDI affectstariff. They consider that FDI decisions are taken before the tariff isimposed to maximize the host-government's political objectivefunction, which is the weighted sum of total campaign gifts andaverage welfare. They show that whether more foreign directinvestments may either increase or reduce the tariff depending onthe relation between the tariff rate and the ratio of the marginalcosts in the home and the foreign country. Unlike our paper,considering the effects of a trade cost reduction on FDI, the causalitybetween FDI and tariff is opposite in their paper.

In a NorthSouth framework, Ekholm et al. (2007) considerexporting back from a host country, and show the implications of afree trade area between the Northern country and the Southern coun-try. However, free trade area in their work eliminates tariff and thecost of FDI between the countries in the free trade area. Moreover,no Southern demand and no Southern producer in their analysis ig-nore the effects of demand and cost asymmetries, thus making theiranalysis significantly different from ours.

The effects of trade costs on international trade can be found froma related literature (see, Laussel and Riezman, 2006; Melitz, 2003, forrecent works). However, these papers do not consider the effects oftrade costs on FDIs. Although the effects of a trade cost reduction onFDI can be found in Helpman et al. (2004), which extends Melitz(2003) with FDI, it conforms to the proximity-concentrationhypothesis.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2shows the implications of market size. Section 3 shows the effects ofcompetition in the product market. Section 4 concludes. The proofsare relegated to Appendix A.

7 There is a related literature which considers the effect of trade cost reduction be-tween the host countries on a multinational firm's incentive for undertaking FDI inone or more host countries (Motta and Norman, 1996; Neary, 2002, 2008; Normanand Motta, 1993). In contrast, we show the effects of trade cost reduction betweenthe home and the host countries on the incentive for FDI. Neary (2008) also providesa sketch similar to our argument under monopoly, yet it is not explicit in terms ofthe demand conditions which create the negative relationship between trade costand FDI. Further, that work does not show the implications of competition, which is an-other important aspect of our paper. In contrast to our paper, which considers horizon-tal FDI where the multinational firm does not fragment production geographically, Carret al. (2001) and Pontes (2007) show that trade cost reduction may increase verticalFDI where the multinational firm fragments production geographically. Theknowledge-capital model of Markusen (2002) shows that higher trade cost increaseshorizontal FDI but it reduces vertical FDI. Hence, unlike our paper, the knowledge-capital model of Markusen is in line with the proximity-concentration hypothesis.Davis (2005) shows that if a foreign firm can fragment its production, thus focusingon vertical FDI, FDI may occur in the absence of trade cost and factor price difference.

-

1940 A. Mukherjee, K. Suetrong / Economic Modelling 29 (2012) 19381945

2. The implications of market size8

Assume that there are two countries: country 1 and country 2.There is a firm in country 1, called firm 1, which has already establishedits business in that country and wants to sell its product to both coun-tries 1 and 2. Firm 1 has two production strategies available: (i) it canproduce in country 1 (the home country) and sell to both markets,9 or(ii) it can relocate its plant to country 2 (the host country) and sell toboth markets from country 2. We call the former strategy as exportand the latter strategy as FDI. As already mentioned, this type of FDIis often called as home-country export platform FDI (Ekholm et al.,2007). Since firm 1 operates only one plant under FDI to serve boththe home and the host countries, we consider full FDI according tothe terminology of Lommerud et al. (2003).

We assume that export to and from country 2 involves the sameand a constant per-unit trade cost, t. Further, the constant marginalcost of production of firm 1 is c1, which is assumed to be zero, forsimplicity.10 It is needless to say that our qualitative results do notdepend on this simplifying assumption of zero marginal cost.

A comment about the type of FDI considered in this paper de-serves attention. Firms often face different types of fixed costs suchas firm-specific and plant-specific fixed costs. As nicely summarizedin Dunn and Mutti (2004), a firm's R&D which generates ideas appli-cable in all locations is a fixed cost specific to the firm as a whole,while the fixed cost of building a factory and installing machinery isspecific to a plant. The existence of high firm-specific fixed costs in-creases the firm's incentive for serving several markets to exploit itsunique knowledge, while high plant-specific costs encourage thefirms to use fewer plants for its total production. For simplicity, wenormalize the firm-specific fixed cost to zero. We also normalize theplant-specific fixed cost to zero if firm 1 sets up one plant. However,an additional plant by firm 1 requires an extra investment of G>0.Appealing to Barros and Cabral (2000), Fumagalli (2003), Bjorvatnand Eckel (2006), Neary (2008) and many others, we assume thatdiseconomies related to plant-specific fixed costs are such that firm1's gain from the extra plant is lower than the extra investment G, im-plying that firm 1 sets up its plant either in country 1 or in country 2.Hence, firm 1 requires exporting back to its home country under FDI.

It must be easy to understand that if the diseconomies created byplantspecific fixed costs are not very high in our analysis, firm 1 setsup one plant in each country to serve the respective market. Hence,the need for exporting back to the home country from the host coun-try plant does not arise, and firm 1 does FDI to serve only the host-country. It is trivial in this situation that the relationship betweenFDI and trade cost follows the prediction of the proximity-concentration theory. Therefore, sufficient diseconomies related toplant-specific fixed cost, which create the need for exporting backto the home country, are important for our analysis.

Assume that the markets are segmented, and the inverse marketdemand functions in countries 1 and 2 are respectively

P1 a1b1q1 1

P2 a2b2q2; 2

where a1>0, a2>0 and Pi and qi show price and output in country i,i=1,2. These demand functions can be generated from the

8 We are grateful to an anonymous referee for pointing out this aspect of the prob-lem to us.

9 In principle, firm 1's export to the host country can be re-exported back to its homecountry. However, since firm 1 is producing in its home country, it does not have theincentive to export to the host country and then re-exported back to the home country,due to the positive trade cost. If firm 1 produces in the home country, it will serve thatcountry from its home plant.10 Our assumption of constant marginal costs of production implicitly assumes thatthe factor prices are given in our analysis. In other words, the input supply curvesare perfectly elastic in both the countries.

representative utility functions Ui aiqi biqi2

2 , i=1,2, in coun-tries 1 and 2, where is the numeraire good, which is traded at acompetitive world price. Therefore, aibi, which shows the value of qiat which the utilities are maximized (or the marginal utilities arezero), can be thought of as a measure of the market size in the ithcountry, i=1, 2.

The game is as follows. At stage 1, firm 1 decides whether to un-dertake FDI or not. At stage 2, firm 1 produces and the profits arerealised. We solve the game through backward induction.

2.1. Selling to both markets from the home country

First consider the situation where firm 1 produces in country 1and sells the product to both countries 1 and 2. In this situation,firm 1's total profit is

11 a1b1q1 q1 a2b2q2t q2: 3

The equilibrium outputs are

q1 a12b1

and q2 a2t2b2

: 4

The second order conditions for profit maximization are satisfied.The outputs of firm 1 are positive in both markets if a2> t, which is as-sumed to hold.

The total equilibrium profit of firm 1, if it produces in country 1, is

11 a1

2

4b1 a2t

2

4b2: 5

2.2. Selling to both markets from the host-country

Now consider the situation where firm 1 produces in country 2,i.e., undertakes FDI, and sells the product to both countries 1 and 2.In this situation, firm 1's total profit is

12 a1b1q1t q1 a2b2q2 q2F: 6

The equilibrium outputs are

q1 a1t2b1

and q2 a22b2

: 7

The secondorder conditions for profit maximization are satisfied.The outputs of firm 1 are positive in both markets if a1> t, which isassumed to hold.

The total equilibrium profit of firm 1 under FDI is

12 a1t 24b1

a22

4b2F: 8

2.3. FDI by firm 1

Firm 1 undertakes FDI if 21>11 or

F bt 2 b1a2b2a1 t b2b1

4b1b2 F : 9

F shows the maximum gain from FDI. Therefore, given F>0, FDIoccurs only if F > 0. It is immediate from (9) that FDI does notoccur for t=0, since, in this situation, F 0. If there is no tradecost, it is trivial that there is no incentive for FDI.

-

1941A. Mukherjee, K. Suetrong / Economic Modelling 29 (2012) 19381945

Proposition 1. Suppose, t>0.

(i) If b1=b2, FDI can occur (i.e., F > 0) if a1ba2.(ii) If b1>b2, FDI can occur only if a2b2 >

a1b1.

(iii) If b1bb2, FDI can occur only if a1ba2.

Proof. See Appendix A.

Now consider the effect of a change in the trade cost on the incen-tive for FDI.

Proposition 2. Assume that FDI can be the equilibrium outcome (i.e.,

F > 0). A lower trade cost increases the incentive for FDI, i.e., Ft b0, if

b1>b2, a1>a2, a2b2 >a1b1

and t2 btba2 ba1 . Otherwise, a lower trade costreduces the incentive for FDI, i.e., Ft > 0.

Proof. See Appendix B.

Proposition 2 shows that a lower trade cost increases the incentivefor FDI if the host-country market is larger than the home-countrymarket (i.e., a2b2 >

a1b1), the host-country demand is more elastic than

the home-country demand (since a1>a2 and b1>b2),11 and thetrade cost is sufficiently high (i.e., t > t2).

The reason for the above result is as follows. A trade cost reductionhas two opposing effects on the incentive for FDI. On the one hand, alower trade cost increases the profit from export to the host country,and, on the other hand, a lower trade cost increases the profit fromexport to the home country. The former effect tends to reduce the in-centive for FDI, while the latter effect tends to increase the incentivefor FDI. Due to the envelope theorem, the effect of trade cost reduc-tion on firm 1's profits depends on its output. Whether firm 1's outputunder export to the host country (which is q2 a2t2b2 ) is greater thanits output under export to the home country (which is q1 a1t2b1 ) de-pends on ai, bi and t, where i=1, 2, thus creating the importance ofthe market size, price elasticity of demand and the trade cost.

If the price intercept of the host-country demand, which is a2, islower than the price intercept of the home-country demand, whichis a1, and the market size is higher in the host country than in thehome country, i.e., a2b2 >

a1b1, two demand curves intersect at the price

b1a2b2a1b1b2 , which is nothing but

t2. Therefore, if tb

t2, the output of firm

1 is higher under export to the host country than under export tothe home country. In this situation, a lower trade cost increases firm1's profit more under export to the host country than under exportto the home country, thus reducing the incentive for FDI. On theother hand, if t > t2, firm 1' profit gain due to a lower trade cost ishigher under export to the home country than under export to thehost country, thus increasing the incentive for FDI.

12 Product patent implies that no other firm except the original innovator can pro-duce similar products through imitation, thus ensuring monopoly to the original inno-vator. Though process patent allows non-infringing imitation, the novelty requirementfor the imitated product or large patent breadth helps to reduce the threat of imitation.13 We have assumed that financial or institutional factors may prevent firm 2 fromexporting. There are works which show that often firms self-sort into being exportersor not. For example, Melitz (2003) shows that the distinction between exporters andnon-exporters can be made by the exogenous productivity difference which is the out-come of a random draw. Davidson et al. (2008) show that the self-selection into beingexporters or not can be the outcome of endogenous heterogeneity across firms. Sinceour focus is not in determining exporters and non-exporters, we assume that noexporting by firm 2 is due to exogenous factors. Even if the choice of exporting is en-dogenous, our qualitative results hold if no exporting is the optimal choice of the host

3. The implications of competition in the product market

The purpose of this section is to show that even if the demandfunctions are the same in the home and the host countries, a negativerelation between trade cost and FDI occurs in the presence of compe-tition in the home country.

Wemodify the model of Section 2 by considering a firm in the hostcountry, called firm 2, which competes with firm 1 in the host countrylike a Cournot duopolist with a homogeneous product. We assumethat firm 2's constant marginal cost of production is c2>0. We as-sume that the demand functions in both markets are the same, andare given by P=aq.

11 It is shown in Nieswiadomy (1986) that a demand curve is more elastic than theother if the price intercept of the former is lower than the latter, irrespective of theslope of the demand function.

There could be several justifications for our assumption of no ex-port by firm 2 to the home country of firm 1. As pointed out byGreaney (2003) and the evidences therein, a buyerseller networkmay be important for both international trade and investment, andasymmetric network effects may generate different production strat-egies for the firms. In our framework, a higher network cost for firm 2may prevent it from selling the product to the home country of firm 1.Alternatively, transportation technologies available to the firms maybe different, and may create prohibitive trade cost for firm 2, thusrestricting firm 2 from selling to the home country of firm 1. As an-other justification, financial constraint may prevent firm 2 fromselling the product to the home country of firm 1. Different patentsystems in these countries may also justify why firm 2 is not sellingthe product to the home country of firm 1. Assuming firm 1 as the in-novator of the product, product patent (or a strong process patent) inthe home country of firm 1 can ensure firm 1's monopoly in thatcountry, while the lack of product patent12 (or a weak process pat-ent) in the host country can create the threat of competition in thatcountry.13 However, we show the implications of export by firm 2in Appendix D.

We consider the following game in this section. At stage 1, firm 1decides whether to undertake FDI or not. As in Section 2, firm 1 sets aplant either in country 1 or in country 2 and serves both countries.14

At stage 2, the firms produce simultaneously and the profits arerealised. We solve the game through backward induction.

3.1. Selling to both markets from the home country

First consider the profit of firm 1 when it decides to produce in thehome country and serves the host country through export. In this sit-uation, firm 1's profit is

11 aq11

q11 aq21q2t

q21; 10

where q11 and q12 denote the outputs of firm 1 in the home and thehost countries respectively, and q2 is the output of firm 2.

If firm 1 produces in its home country, the profit of firm 2 is

12 aq21q2c2

q2: 11

The equilibrium outputs are

q11 a2; q21

a2t c23

and q2 a2c2 t

3: 12

The secondorder conditions for profit maximisation are satisfied.The equilibrium output of firm 2 is positive for a non-negative tradecost if c2b a2, and the equilibrium output of firm 1 under export isalways positive if tb a2. We assume that these conditions hold.

country firm.14 As in footnote 9, if firm 1 produces in the home country, it will serve that countryfrom its home-country plant, since it does not have the incentive to export to the hostcountry and then re-exported back to the home country, due to the positive trade cost.

-

1942 A. Mukherjee, K. Suetrong / Economic Modelling 29 (2012) 19381945

If all the outputs in (12) are positive, the respective equilibriumprofits of firms 1 and 2 are

11 a2

2 a2t c2

3

213

12 a2c2 t

3

2: 14

3.2. Selling to both markets from the host country

Firm 1 has an alternative strategy of investing in the host countryand selling the product to both countries from the host country. If itinvests and sells from the host country, the presence of the tradecost reduces its profit in the home country compared to the situationwhere it produces in the home country. However, by investing in thehost country, and therefore, by saving the trade cost of exporting tothe host country from the home country, firm 1 can extract highermarket share and profit in the host country compared to the situationwhere it exports from the home country. If the latter effect dominatesthe former, firm 1 finds it profitable to invest in the host country. Thefollowing analysis shows that the marginal cost difference betweenthe firms plays an important role in this respect.

If firm 1 undertakes FDI and sells the product to both marketsfrom the host country, its profit is

21 aq11t

q11F aq21q2

q21: 15

If firm 1 undertakes FDI, the profit of firm 2 is

22 aq21q2c2

q2: 16

The equilibrium outputs are

q11 at2

; q21 a c2

3and q2

a2c23

: 17

The secondorder conditions for profit maximisation are satisfied.Given our assumptions of c2b a2 and tb

a2, the equilibrium outputs of

both firms are positive under FDI by firm 1.If all the outputs in (17) are positive, the respective equilibrium

profits of firms 1 and 2 are

21 at2

2 a c2

3

2F 18

22 a2c2

3

2: 19

3.3. FDI by firm 1

Comparison of (13) and (18) shows that 11b

21 if

a2

2

a2t c23

2b

at2

2 a c2

3

2F, or

Fb

t 2a7t 16c2 36

F: 20

F* shows firm 1's maximum gain from FDI. We find that F*>0 pro-vided tb 2 8c2a 7 t . However, t > 0 if c2 > a8c2 , and tb a2 if c2b 11a32 c2 .

Hence, the following result is immediate.

Proposition 3. Assume that c2 0; a2

and t 0; a2

. Firm 1 undertakesFDI if the marginal cost of firm 2 is sufficiently high (i.e., c2 c2 ; a2

),

trade cost is sufficiently low (i.e., t 0; t

), and firm 1's maximumgain from FDI is greater than the fixed cost of FDI (i.e., FbF*).

Proposition 3 shows that FDI occurs only if c2 is sufficiently highand t is sufficiently low so that F*>0. Otherwise, firm 1 has no incen-tive for undertaking FDI.

The above result can be explained in the following way. Imagine asituation with no host country firm. Hence, firm 1 is a monopolistunder both export and FDI. In this situation, firm 1 never prefers FDIsince its gross profit from undertaking FDI and exporting back to thehome country is equal to its gross profit from serving both marketsfrom the home country. However, the incentive for FDI may ariseunder competition in the host country. On the one hand, FDI helpsfirm 1 to steal market share from firm 2 compared to export from thehome country. This benefit from FDI increases with the higher cost ofthe host country firm. On the other hand, FDI creates a negative effecton firm 1's profit by reducing its profit in the home country due to thepresence of the trade cost. The fixed cost of FDI creates further negativeimpact on firm 1's profit under FDI. These negative effects of FDI reducewith a lower trade cost and a lower fixed cost of FDI. If firm 2's margin-al cost is high and both the trade cost and the fixed cost of FDI are low,the positive effect of FDI dominates its negative effects, and makes FDIprofitable for firm 1 compared to export.

Now we see the relation between trade cost and the incentive forFDI. It follows from (20) that if c2 a8c2 , we get F*b0 for any t>0.Hence, FDI is not an equilibrium for c2 a8. Thus, to show the effectsof a trade cost reduction on the incentive for FDI, we restrict our at-tention to c2 > c2 .

Proposition 4. Assume t 0; a2

and c2 c2 ; a2

. A lower trade cost in-

creases the incentive for FDI, i.e., F

t b0, if t >8c2a

7 t . Otherwise, alower trade cost reduces the incentive for FDI, i.e., F

t > 0.

Proof. See Appendix C.

The reason for Proposition 4 is as follows. If the trade cost reduces,it increases firm 1's profit from export to and from the host country.The effect of a trade cost reduction on firm 1's profit under exportto the host country depends on its output under export to the hostcountry and the strategic effect of the trade cost reduction on firm2's output. We get that the trade cost reduction increase firm 1's prof-

it under export to the host country by q21 Pqq2t 1

4 a2tc2 9 . On

the other hand, the effect of a trade cost reduction on firm 1's profitunder export to the home country depends on its output under ex-port to the home country, which is given by q11 at2 . Hence, givena, the net effect depends on c2 and t. The comparison of these effectsshows that a trade cost reduction increases the incentive for FDI if thelatter effect dominates the former (i.e., increase in firm 1's profitunder export to the home country is more than its profit rise under

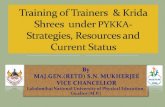

export to the host country), and this happens if t > 8c2a7 t .Fig. 1, which shows the relationship between t and F*, for a given

c2, is a graphical representation of Proposition 4.

We plot five curves (A, B, C, D and E) in Fig. 1. As c2 increases, wemove upward between the curves. Curves A and B correspond to thesituations where c2 > 11a32 (i.e., t >

a2) and c2 11a32 (i.e., t a2). Therefore,

these curves represent the situations where F*>0 for t 0; a2

. Curves

D and E correspond to the situations where c2 a8 (i.e., t 0) and c2b a8(i.e., tb0). Hence, these situations represent the cases of F*b0 fort 0; a2

. Curve C corresponds to the situation where c2 a8 ; 11a32

.

Hence, this situation represents the case where F*>0 for tb 2 8c2a 7 tbut F*b0 for t > t .

Fig. 1 provides the following information. First, it shows that if c2 issmall (which refers to curves D and E), FDI never occurs, since F*b0 in

-

Fig. 1. The relationship between trade cost and the incentive for FDI.

1943A. Mukherjee, K. Suetrong / Economic Modelling 29 (2012) 19381945

these situations. Second, considering FDI as the equilibrium outcome(which occurs if c2 is high and is shown by curves A, B and C), a lowertrade cost increases (reduces) the incentive for FDI for tb > t .15 For ex-ample, curve A shows that a lower trade cost increases the incentive forFDI if t > ta . Lastly, Fig. 1 shows that as c2 increases, the possibility ofhigher FDI following a trade cost reduction falls. This is representedby a rightward move of the maximum points of the curves. For agiven trade cost, as the cost of firm 2 increases, it increases firm 1'scompetitive advantage against firm 2, thus reducing firm 1's incentivefor FDI for getting a higher competitive advantage in the host countrymarket. Hence, as c2 increases, it increases the range of the trade costsover which a lower trade cost reduces the incentive for FDI.

So far, we have assumed that firm 2 serves only the host countrymarket. However, if firm 2 can export to the home country of firm 1and faces the trade cost t, we get that (see Appendix D) FDI occursonly for those higher trade costs where firm 2 does not find export to thehome country profitable. However, a trade cost reduction may either in-crease or decrease the incentive for FDI in the presence of export by firm 2.

4. Conclusion

While the wellestablished proximity-concentration theory sug-gests that, ceteris paribus, a lower trade cost reduces FDI, there isample evidence showing a negative relation between trade cost andFDI. We use simple models to show that the possibility of exportingback to the home country from a host country may be a reason forcreating the negative relation between trade cost and FDI. We high-light the roles of market demand and competition in the product mar-ket. Thus, our paper complements previous works explaining anegative relation between trade cost and FDI in the presence of eitherinput market imperfection or scale economies.

We have shown that the conclusion of the proximity-concentrationhypothesis may not hold in the presence of a home-country exportplatform-FDI. A natural extension of our paper is to consider how com-petition between the foreign firms affects our result. In this respect, themarginal cost difference between the home-country and the host-country firms as well as between the home-country firms may playimportant roles.16

15 Even if curves D and E show negative relationship between t and F*, FDI never oc-curs in these cases. Hence, there is no meaning for considering the effects of trade coston the incentive for FDI in these situations.16 See Yomogida (2008) for a recent work on oligopolistic competition in internation-al trade when the countries have different technologies.

Secondly, it would also be interesting to see how our results areaffected in the presence of a home-country export-platform FDItogether with a third-country export-platform FDI, where a foreignfirm determines its plant location among the host countries.This will allow us to show the effects of regional trade agreementon FDI.17

Finally, the effects of a trade cost reduction on FDI in the presenceof both horizontal and vertical FDIs are also worth considering. In thisrespect, not only trade in products but also trade in services deserveattention.18

Appendix A

Proof of Proposition 1. It follows from (9) that F > 0 if

2 b1a2b2a1 t b2b1 > 0: A1

(i) If b1=b2, (A1) holds if a1ba2.

(ii) If b1>b2, (A1) holds if tbt 2 b1a2b2a1 b1b2 . Since t>0, the condi-tion tbt satisfies only if t > 0 or a2b2 >

a1b1.

(iii) If b1bb2, (A1) holds if t > t . Since the requirements for positiveoutputs imply ai> t, i=1, 2, the conditions t > t and ai> tsatisfy together only if a1ba2.

Appendix B

Proof of Proposition 2. We get that Ftb 0 if

b1a2b2a1 t b2b1 b0: B1

If b1=b2, we know from Proposition 1 that FDI can occur provided

a1ba2. Hence, Ft > 0 for b1=b2.If b1>b2, (B1) shows that

Ft

b 0 for t

>

t2. However, we know from

Proposition 1 that if b1>b2, FDI can occur provided a2b2 >a1b1, which en-

surest > 0, thus creating the possibility of tb t2. Since the requirementsfor positive outputs imply that t must be less than ai, i=1,2, we canalso have the possibility of t > t2 provided

t2bmin a1; a2f g, which hap-

pens if a1>a2. Hence, if b1>b2, a1>a2 and a2b2 >a1b1, we get Ft > 0 for

0btb t2 andFt b0 for

t2 btba2 ba1 .

If b1bb2, (B1) shows that Ft

b 0 if t

bt2. However, we know from

Proposition 1 that, if b1bb2, FDI can occur for t > t . Hence, if b1bb2and FDI can be the equilibrium outcome, t cannot be less than t2, and

we get Ft > 0 for b1bb2.The above discussion shows that, if FDI can be the equilibrium out-

come, a lower trade cost increases the incentive for FDI (i.e., Ft b0) if

b1>b2, a1>a2, a2b2 >a1b1

and t2 btba2 ba1 . Otherwise, the relation be-tween trade cost and FDI is positive, i.e., Ft > 0.

Appendix C

Proof of Proposition 4. Differentiating F* with respect to t, we find

that F

tb 0 if 16c27t2a 7t b 0 or t > 8c2a7 t , where 0btb a2 for

c2 c2 ; a2

. Hence, a lower trade cost increases the incentive for FDI,

i.e., F

t b0, if t > t but it reduces the incentive for FDI, i.e.,Ft > 0, for

tbt .

17 See MacDermott (2007) for a recent work on regional trade agreement and FDI.18 See Henry (2005), Kikuchi and Iwasa (2010) and Long et al. (2005) for recentworks on trade in services.

-

1944 A. Mukherjee, K. Suetrong / Economic Modelling 29 (2012) 19381945

Appendix D

D The implications of export by firm 2 on the relation betweentrade cost and FDI: Assume that firm 2 faces the trade cost t and canexport to the home country of firm 1. We also assume that c2b a2 andtb a2, which ensure positive outputs by firm 1 in both markets and pos-itive output by firm 2 in the host-country market. However, these as-sumptions may not ensure that firm 2 always exports to the homecountry of firm 1.

It may worth noting that we restrict firm 2 from investing in thehome country. Since the possibility of FDI by firm 2 will have furtherstrategic effect on the investment decision of firm 1, we restrict firm 2from investing in the home country of firm 1. This assumption maybe justified by considering firm 2 as a capital constrained firm (see,e.g., Norman and Motta, 1993, for similar assumption in a differentcontext).

If firm 1 exports, the profits of firms 1 and 2 are respectively

11 aq11q12

q11 aq21q22t

q21 D1

and

12 aq11q12c2t

q12 aq21q22c2

q22; D2

where q11 and q12 (respectively q21 and q22) denote the outputs of firm 1(respectively firm 2) in the home and the host countries respectively.

The equilibrium outputs areq11 ac2t3 , q21 a2tc23 , q12 a2c22t3and q22 a2c2t3 .

Firm 2 exports to the home country of firm 1 if and only if tb a2c22 .The profits of firms 1 and 2 are respectively

11 a c2 t

3

2 a2t c2

3

2; for t a2c2, the profits of firms 1 and 2 are respectively given by(18) and (19) in the text.

The following three intervals need to be considered to deter-

mine the investment decision of firm 1: (i) t 0; a2c22

, (ii) ta2c2

2 ; a2c2

, and (iii) t a2c2; a2

. The interval a2c2; a2

is

non-empty if c2 > a4.

If t 0; a2c22

, firm 2 exports irrespective of firm 1's decision on

export and FDI. Hence, we need to compare (D3) and (D7) to deter-mine firm 1's decision on FDI. The comparison of these expressionsshows that firm 1 prefers export than FDI.

If t a2c22 ; a2c2

, firm 2 exports if firm 1 undertakes FDI, but

firm 2 does not export if firm 1 produces in the home country (i.e., ex-ports). Hence, (13) and (D7) are the relevant expressions to be com-pared in order to determine firm 1's decision on FDI. The comparisonshows that firm 1 prefers export to FDI.

Lastly, consider the situation where t a2c2; a2

. Recall that thissituation can occur provided c2 > a4. In this situation, firm 2 does notexport, irrespective of firm 1's FDI decision, and the analysis is similarto subsection 3.3, where export by firm 2 is not allowed. Here, firm 1

undertakes FDI if F b t 2a7t16c2 36 F, where F*>0 provided

tb 2 8c2a 7 t . Since we have c2 > a4, it implies that t > 0. However, t >a2c2 if c2 > 3a10 and tb a2 if c2b 11a32 c2 . We consider the cases of0btba2c2 and a2c2 b t separately.

If a4bc2b3a10, we get 0btba2c2. Since we consider t a2c2; a2

, it

implies F*b0 and firm 1 exports in this situation. Here, a trade cost re-duction satisfying t a2c2; a2

has no impact on firm 1's FDI decision.

If c2 > 3a10, we get t > a2c2, and firm 1 undertakes FDI fort a2c2; t

and FbF*. We get that F

t

b 0 if t

>

8c2a7 , where

8c2a7

b a2c2 for c2 b 4a11. Hence, a lower trade cost increases the incen-

tive for FDI if either c2 3a10 ; 4a11

or c2 4a11 ; a2

and t > 8c2a7 . However, if

c2 4a11 ; a2

and tb 8c2a7 , a lower trade cost reduces the incentive for FDI.The above discussion shows that a lower trade cost may either

increase or decrease the incentive for FDI in the presence of exportby firm 2.

References

Anderson, J.E., Wincoop, E.V., 2003. Gravity with gravitas: a solution to the borderpuzzle. American Economic Review 93, 170192.

Anderson, J.E., Wincoop, E.V., 2004. Trade costs. Journal of Economic Literature XLII,691751.

Baier, S.L., Bergstrand, J.H., 2009. Bonus vetus OLS: a simple method for approximatinginternational trade-cost effects using the gravity equation. Journal of InternationalEconomics 77, 7785.

Barros, P.P., Cabral, L., 2000. Competing for foreign direct investment. Review of Inter-national Economics 8, 360371.

Bhuiyan, W., 2003. A foreign investor's experience in with administrative barriers inSouth Asia. Keynote address in South Asia FDI Roundtable, Maldives 9-1 April.

Bjorvatn, K., Eckel, C., 2006. Policy competition for foreign direct investment betweenasymmetric countries. European Economic Review 50, 18911907.

Brainard, S.L., 1997. An empirical assessment of the proximity-concentration tradeoffbetween multinational sales and trade. American Economic Review 87, 520544.

Carr, D.L., Markusen, J.R., Maskus, K.E., 2001. Estimating the knowledge-capital modelof the multinational enterprise. American Economic Review 91, 693708.

Davidson, C., Matusz, S.J., Shevchenko, A., 2008. Globalization and firm level adjust-ment with imperfect labor markets. Journal of International Economics 75,295309.

Davis, R.B., 2005. Fragmentation of headquarter services and FDI. North AmericanJournal of Economics and Finance 16, 6179.

Dunn Jr., R.M., Mutti, J.H., 2004. International Economics, 6th edition. Routledge,London.

Eaton, J., Kortum, S., 2002. Technology, geography, and trade. Econometrica 70,17411779.

Ekholm, K., Forslid, R., Markusen, J.R., 2007. Export-platform foreign direct investment.Journal of the European Economic Association 5, 776795.

Ethier, W.J., Markusen, J.R., 1996. Multinational firms, technology diffusion and trade.Journal of International Economics 41, 128.

Feenstra, R.C., 2004. Advanced International Trade: Theory and Evidence. PrincetonUniversity Press, Princeton, NJ.

Feinberg, S.E., Keane, M.P., Bognanno,M.F., 1998. Trade liberalization and delocalisation:newevidence fromfirm-level panel data. Canadian Journal of Economics 31, 749777.

-

1945A. Mukherjee, K. Suetrong / Economic Modelling 29 (2012) 19381945

Fumagalli, C., 2003. On the welfare effects of competition for foreign direct invest-ments. European Economic Review 47, 963983.

Greaney, T.M., 2003. Reverse importing and asymmetric trade and FDI: a networkexplanation. Journal of International Economics 61, 453465.

Grossman, G.M., Helpman, E., 1996. Foreign investment with endogenous protection.In: Feenstra, R., Grossman, G.M., Irwin, D. (Eds.), The Political Economy of TradePolicy. The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Helpman, E., Melitz, M.J., Yeaple, S.R., 2004. Export versus FDI with heterogeneousfirms. American Economic Review 94, 300316.

Henry Jr., W., 2005. Fragmented trade and manufacturing servicesexamples for anon-convex general equilibrium. International Review of Economics and Finance14, 273295.

Hines Jr., J.R., 1995. Forbidden payments: foreign bribery and American business after1977. NBER working papers, 5266.

Horstmann, I.J., Markusen, J.R., 1987. Strategic investments and the development ofmultinationals. International Economic Review 28, 109121.

Kikuchi, T., Iwasa, K., 2010. A simple model of service trade with time zone differences.International Review of Economics and Finance 19, 7580.

Laussel, D., Riezman, R., 2006. Transportation costs and NorthSouth trade. Asia-PacificJournal of Accounting and Economics 13, 111122.

Lommerud, K.E., Meland, F., Srgard, L., 2003. Unionised oligopoly, trade liberalizationand location choice. The Economic Journal 113, 782800.

Long, N.V., Riezman, R., Soubeyran, A., 2005. Fragmentation and services. NorthAmerican Journal of Economics and Finance 16, 137152.

MacDermott, R., 2007. Regional trade agreement and foreign direct investment. NorthAmerican Journal of Economics and Finance 18, 107116.

Markusen, J.R., 2002. Multinational firms and the theory of international trade. MITPress, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Markusen, J.R., Venables, A.J., 1998. Multinational firms and the new trade theory. Jour-nal of International Economics 46, 183203.

Melitz, M., 2003. The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregateindustry performance. Econometrica 71, 16951726.

Motta, M., 1992. Multinational firms and the tariff-jumping argument. EuropeanEconomic Review 36, 15571571.

Motta, M., Norman, G., 1996. Does economic integration cause foreign direct invest-ment? International Economic Review 37, 757783.

Neary, J.P., 2002. Foreign direct investment and the single market. The ManchesterSchool 70, 291314.

Neary, J.P., 2008. Trade costs and foreign direct investment. International Review ofEconomics and Finance 18, 207218.

Nieswiadomy, M., 1986. A note on comparing the elasticities of demand curves. TheJournal of Economic Education 17, 125128.

Norback, P.-J., Persson, L., 2007. Investment liberalizationwhy a restrictive cross-border merger policy can be counterproductive. Journal of International Economics72, 366380.

Norman, G., Motta, M., 1993. Eastern European economic integration and foreign directinvestment'. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy 2, 483508.

Pontes, J.P., 2007. A non-monotonic relationship between FDI and trade. EconomicsLetters 95, 369373.

Smith, A., 1987. Strategic investment, multinational corporations and trade policy.European Economic Review 31, 8996.

UNCTAD, 2002. World investment report: transnational corporations and exportcompetitiveness. United Nations, New York and Geneva.

UNCTAD, 2006.World Investment Report: FDI FromDeveloping and Transition Economies:Implications for Development. United Nations, New York and Geneva.

UNCTAD Handbook of Statistics, 2004. China Set to Stay Growth Course. UNCTAD,Switzerland.

Yomogida, M., 2008. Competition, technology, and trade in oligopolistic industries.International Review of Economics and Finance 17, 127137.

Trade cost reduction and foreign direct investment1. Introduction2. The implications of market size88We are grateful to an anonymous referee for pointing out this aspect of the problem to us.2.1. Selling to both markets from the home country2.2. Selling to both markets from the host-country2.3. FDI by firm 13. The implications of competition in the product market3.1. Selling to both markets from the home country3.2. Selling to both markets from the host country3.3. FDI by firm 14. ConclusionAppendix AAppendix BAppendix CAppendix DReferences