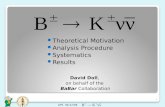

Incorporating Motivation into a Theoretical Framework for ...

MOTIVATION IN THE ELDERLY: A THEORETICAL … · MOTIVATION IN THE ELDERLY: A THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK...

Transcript of MOTIVATION IN THE ELDERLY: A THEORETICAL … · MOTIVATION IN THE ELDERLY: A THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK...

MOTIVATION IN THE ELDERLY: A THEORETICALFRAMEWORK AND SOME PROMISING FINDINGS

ROBERT J. VALLERANDLaboratoire de Psychologie Sociale

Universite du Quebec a Montreal

BRIAN P. O'CONNORLakehead University

ABSTRACTDespite a widespread concern with the well-being of elderly people, very little is knownabout the motivation behind everyday behaviours in old age. In this paper a theoreticalframework that has been found useful in research on young adults is suggested as a promisingdirection for research on the psychology of motivation in the elderly. This framework (Deci& Ryan, 1985a) posits the existence of four types of motivation (intrinsic, self-determinedextrinsic, nonself-determined extrinsic, and amotivation) which are assumed to have anumber of consequences for adaptation and well-being. After presenting the theory, wereview findings from an ongoing research program that has found that the four types ofmotivation can be reliably measured and are related to other important aspects of the livesof elderly people in a theoretically meaningful manner. Suggestions are made for furtherresearch and for potential applications.

One of the most significant changes takingplace in Canadian society is the growing numberof older adults. For example, the population ofCanadian adults over the age of 65 has climbedfrom approximately 4% in 1900 to 9.7% in 1981,and is expected to reach 19.6% by 2021 (Statis-tiques Canada, 1985, Projection #3). In otherwords, soon almost one out of five individuals inCanada will be over 65 years. Similar trends areoccurring in the United States (Allan & Brotman,1981).

Accompanying this demographic trend hasbeen a growing realization among researchersand practitioners of the importance of under-standing the processes involved in aging. In psy-chology, much of the research has focused oncognitive changes, on mental health, on living

This paper was prepared while the first author was sup-ported by research grants from the Social Sciences and Hu-manities Research Council of Canada, le Fonds pour laformation des chercheurs et I'aide a la recherche (FCARQuebec), le Conseil quebecois de la recherche sociale, and theUniversite du Quebec a Montreal. The second author wassupported by a postdoctoral fellowship from la FondationUQAM during his stay at the Laboratoire de PsychologicSociale.

Reprint requests should be addressed to Robert J. Vallerand,Laboratoire de Psychologie Sociale, Universite du Quebec aMontreal, C.P. 8888, Station "A". Montreal, QC, CanadaH3C 3P8.

environments, and on the psychology of deathand dying (see Belsky, 1984; Binstock & Shanas,1985; Bin-en & Schaie, 1985).

While this research has significantly increasedour understanding of the psychology of aging,relatively little is known about motivation in theelderly. Textbooks and handbooks on aging usu-ally do not have chapters on this topic due to alack of research. Those authors who have dis-cussed the topic (e.g., Kleiber & Maehr, 1985;Schaie & Willis, 1986; Veroff & Veroff, 1980;Wigdor, 1980), have been forced to extrapolatefrom research with young subjects, to draw infer-ences from their own clinical experience, or tooffer speculations based on other theoretical in-terests. The relevant empirical research is eithernot very "psychological," or has dealt with moti-vation only tangential ly.

For example, there has been work on changesin biological drives (Eisdorfer & Cohen, 1980;Woodruff, 1975), changes in level of energy andarousal (Thompson & Nowlin, 1973), and onchanges in the central nervous system (Walker &Hertzog, 1975; Wigdor, 1980). These discussionsare sometimes based on dated concepts fromanimal research, and their applicability to elderlyhumans is not always evident.

538 Canadian Psychology / Psychologie Canadienne, 1989, 30:3

Motivation in the Elderly 539

Other research (see Schulz, 1982) has focusedon whether elderly people should find new inter-ests and friends to replace activities from theirworking life (activity theory), or reduce theirnumber of activities and contacts in order to"slow down and enjoy life" (disengagementtheory). Most of this research has been conductedby sociologists, and the motivation of elderlypersons themselves on this issue is rarely men-tioned and deserves closer attention.

One can also find discussions of how the-oretical frameworks developed from research onyoung adults (e.g., on achievement motivation)may apply to the elderly (e.g., Kleiber & Maehr,1985; Maehr & Kleiber, 1981; Reker & Wong,1988; Veroff & Veroff, 1980). However, littleempirical work has been conducted to date (seeDie, Seelbach, & Sherman, 1987; Steinkamp &Kelly, 1985, for exceptions).

Finally, there has been much interest in theconcepts of locus of control (Cicirelli, 1987),perceived control (Bakes & Bakes, 1986; Monty& Perlmuter, 1987; Rodin, 1986, 1987), self-efficacy (Holahan & Holahan, 1987a, b; Wood-ward & Wallston, 1987), and learned help-lessness (Abramson, Seligman, & Teasdale,1978; White & Janson, 1986). In this literature itis often mentioned that a lack of control (or self-efficacy) can reduce motivation. However, theprime concern has been with perceptions andbeliefs about control and self-efficacy and withthe consequences of such beliefs, and not withmotivation per se. Further, much of the work oncontrol has focused on reactions to stressful lifeevents and not on more common, everydaybehaviour. As will be seen below, control may bequite important in the initiation and regulation ofsuch behaviour.

The issue of motivation in the elderly deservescloser attention for a number of reasons. First, itwould help us understand the factors that regulatebehaviour in one of the most prominent agegroups in society. Second, old age is a periodduring which there is physical decline, cognitivechanges, a loss of energy, changing social rolesand interactions, and often a change in livingenvironment. These experiences may involvegrowing perceptions of incompetence or feelingsof reduced self-determination—two factors thatare known to affect motivation (Deci & Ryan,1985a). Understanding the role of motivation inthese changes is necessary for a more completepicture of the psychological processes involved

in aging. Third, motivation research would leadto a better understanding of the factors that influ-ence mental and physical health among the el-derly, because research on young adults hasfound motivation to have a number of conse-quences for adjustment and well-being (Deci &Ryan, 1985a; Maddi & Kobasa, 1982). Finally,understanding the nature of motivation in theelderly would suggest ways of restructuring liv-ing environments to enhance motivation and itsassociated consequences. According to Wigdor,(1980, p. 245), "a better understanding of moti-vational changes with aging would be useful indeveloping programs and environments whichwould result in optimal functioning."

The purposes of this paper are threefold. Oneis to present a theoretical framework for researchon the psychology of motivation in the elderly. Asecond is to review findings from an ongoingresearch program that has used this framework.Finally, we suggest directions for further researchand for potential applications.

Motivation in the Elderly: A TheoreticalFramework

Motivation refers to the forces that initiate,direct, and sustain behaviour (Petri, 1981) andhas been studied from several perspectives. Forexample, some have focused on instinctual drives(e.g., Freud, 1962/1923), whereas others havefocused on environmental contingencies(Skinner, 1953). In this section we outline a morerecent theoretical perspective that has emergedfrom empirical research on young people (Deci,1971, 1975; Deci & Ryan, 1985a). This perspec-tive distinguishes between intrinsic, self-determined extrinsic, nonself-determinedextrinsic, and amotivation. After defining thesefour kinds of motivation, we describe some of theconsequences and determinants of these types ofmotivation, and state how they may apply to thelives of elderly people.

Intrinsic, Extrinsic, and Amotivation

Intrinsically motivated behaviours are en-gaged in for their own sake—for the pleasure andsatisfaction derived from their performance(Deci, 1971). They are voluntarily performed inthe absence of material rewards or constraints(Deci & Ryan, 1985a, 1987). The elderly personwho plays cards for the inherent pleasure derivedfrom doing so is intrinsically motivated toward

540 Canadian Psychology / Psychologie Canadienne, 1989, 30:3

that activity. Intrinsic motivation is thought tostem from the needs to feel competent and self-determined (Deci, 1975; Deci & Ryan, 1985a).Activities that lead the individual to experiencefeelings of competence and/or self-determinationare intrinsically rewarding and are likely to beperformed again.

Extrinsically motivated behaviours are per-formed to receive or avoid something once theactivity is terminated, and are not performed fortheir inherent experiential aspects (Deci, 1975;Kruglanski, 1978). It was originally thought thatextrinsic motivation referred to nonself-deter-mined behaviour—to behaviour that could beprompted only by external contingencies. Morerecently, however, Deci, Ryan and their col-leagues (Connell & Ryan, 1986; Deci & Ryan,1985a; Ryan, Connell, & Deci, 1985; Ryan, Con-nell, & Grolnick, in press) have proposed thatthere are different types of extrinsic motivation,some of which may be self-determined. In thispaper we will distinguish between two broadtypes of extrinsic motivation only: self-deter-mined and nonself-determined.

"Nonself-determined extrinsic motivation"occurs when behaviour is externally regulated(usually through rewards or constraints). For ex-ample, nursing home residents may participate incard games because they feel urged to do so bythe staff. In this case, an activity that can orshould be fun is performed in order to avoidnegative consequences (e.g., criticism from thestaff). The motivation is extrinsic because thereason for participation lies outside the activityitself. Furthermore, the behaviour is not chosenor self-determined.

Nonself-determined extrinsic motivation mayalso be fuelled by a desire for rewards. For exam-ple, a nursing home resident might agree to playcards "because the doctor told me that it wouldbe good for me." In this case the motivation isstill extrinsic and nonself-determined, but theinstigating factor is the desired reward (e.g.,praise from the doctor). Regardless of whetherthe goal of behaviour is to obtain rewards or toavoid sanctions, the individual experiences anobligation to behave in a specific way, and feelscontrolled by the reward or by the constraint(Deci & Ryan, 1985a).

In contrast, "self-determined extrinsic motiva-tion" occurs when a behaviour is valued by theindividual and is perceived as being chosen byoneself. Behaviour is internally regulated. An

example is the elderly person who plays cards"because I feel that it is a good way to keep mymind sharp." The motivation is extrinsic becausethe activity is not performed for itself but as ameans to an end (to keep one's mind sharp).However, the behaviour is nevertheless self-de-termined: the individual has decided that playingcards is beneficial. The person experiences asense of direction and purpose, instead of obliga-tion and pressure, in performing the behaviour.

Apart from intrinsic and extrinsic motivation,Deci & Ryan (1985a) claim that a third construct,"amotivation," must be considered to fullyunderstand human behaviour. Individuals areamotivated when they perceive a lack of contin-gency between their behaviour and outcomes.There is an experience of incompetence and lackof control. Amotivated behaviours are neitherintrinsically nor extrinsically motivated: they arenonmotivated. For example, a nursing home res-ident might say, "I really don't know why I playcards; I don't see what it does for me." There areno rewards (neither intrinsic nor extrinsic) andparticipation in the activity will eventually cease.Learned helplessness (Abramson, Seligman, &Teasdale, 1978) is an eventual consequence ofamotivation. Amotivated behaviours are the leastself-determined because there is no sense of pur-pose, and no expectation of reward or of thepossibility of changing the course of events.

In sum, a distinction has been made betweenfour types of motivation with varying degrees ofself-determination. Intrinsically motivated be-haviours are the most self-determined whereasamotivated behaviours are the least self-determined.

Consequences of Intrinsic, Extrinsic andAmotivation

Given that behaviour can be intrinsically,extrinsically, or amotivated, what are theconsequences of these kinds of motivation foreveryday life and well-being? Because the fourkinds of motivation are supposedly on a contin-uum from high to low self-determination (Deci& Ryan, 1985a), and because self-determinationis associated with enhanced psychological func-tioning (Deci, 1980), one would expect a corre-sponding pattern of consequences. That is, onemight expect intrinsic motivation to have themost positive consequences, followed by self-de-termined extrinsic motivation. One might alsoexpect nonself-determined extrinsic motivation

Motivation in the Elderly 541

and especially amotivation to be associated withnegative consequences.

These predictions have been confirmed in re-cent research on young adults in a variety of lifesettings (e.g., education, sports, the workplace,interpersonal relationships). The more self-deter-mined forms of motivation lead to greater cogni-tive flexibility, enhanced conceptual learning,greater interest, a more positive emotional tone,higher self-esteem, higher levels of marital hap-piness, greater life satisfaction, higher levels ofcreativity, performance and persistence, and havepositive effects on health in stressful situations(Blais, Sabourin, Boucher, & Vallerand, 1988;Boggiano & Barrett, 1985; Deci & Ryan, 1985a,1987; Kobasa, 1979; Maddi & Kobasa, 1982;Vallerand & Bissonnette, 1988; Vallerand, Blais,Briere & Pelletier, in press). It would thereforeseem worthwhile to examine these forms of mo-tivation in the elderly. If similar findings emerge,the implication would be that the physical andmental health of elderly people can be sustained,in part, by enhancing intrinsic and self-deter-mined extrinsic motivation, and by preventingnonself-determined extrinsic motivation andamotivation. The following is a brief review ofsome factors that have been found to affect mo-tivation.

Determinants of Intrinsic, Extrinsic, andAmotivation

Much of the work on the determinants of in-trinsic, extrinsic, and amotivation has been basedon cognitive evaluation theory (Deci, 1975; Deci& Ryan, 1980, 1985a, 1987) according to whichtwo key factors affect motivation: perceivedlocus of causality and perceptions of compe-tence. Changes in motivation occur when thereare changes in either of these processes. Factorsthat lead to an internal perceived locus of causal-ity enhance feelings of self-determination, whichin turn enhance intrinsic motivation. On the otherhand, when individuals perceive situations to becontrolling, the perceived locus of causality be-comes more external, self-determination is di-minished, and intrinsic motivation is decreased.For example, providing nursing home residentswith choice regarding if or when to participate inactivities should produce an internal locus ofcausality which should enhance intrinsic motiva-tion. On the other hand, forcing residents to par-ticipate in activities should lead to an external

locus of causality, which should undermine in-trinsic motivation.

Research on young adults has consistently sup-ported these hypotheses. Enhancing self-determination through choice increases intrinsicmotivation (e.g., Swann & Pittman, 1977;Zuckerman, Porac, Lathin, Smith, & Deci, 1978),whereas experiences that reduce self-determination (e.g., evaluation apprehension,surveillance, deadlines) lead to an external locusof causality and decreased intrinsic motivation(see Deci & Ryan, 1985a, 1987).

Promoting self-determination should also en-hance self-determined extrinsic motivation: theindividual will experience a sense of purpose anddirection in the performance of activities that arenot inherently interesting. On the other hand, adecrease in feelings of self-determination shouldincrease nonself-determined extrinsic motivationand eventually amotivation, because the individ-ual may become dependent upon others to pro-vide direction. For example, encouragingresponsibility for personal self-maintenance ac-tivities among nursing home residents (e.g.,Jameton, 1988) should lead to an internal locusof causality which should augment self-determined extrinsic motivation toward these ac-tivities. On the other hand, if personalself-maintenance activities are regularly per-formed by the staff without encouragement forself-responsibility, there is a risk of inducing anexternal locus of causality which could enhancenonself-determined extrinsic motivation, depen-dence on the staff, and perhaps eventuallyamotivation.

While research has yet to focus explicitly onthe link between self-determination and motiva-tion in the elderly, many studies have found thatproviding elderly people with choices (Moos,1981; Monty & Perlmuter, 1987; Wolk & Telleen,1976), personal responsibility (Langer & Rodin,1976; Rodin & Langer, 1977), or control(Haemmerlie & Montgomery, 1987; Schulz,1976) enhances feelings of self-determinationand has positive effects on adjustment and well-being. While there is considerable debate overhow self-determination exerts its effects (Bakes& Baltes, 1986), one explanation, suggested bythe present motivational approach (Deci & Ryan,1985a), is that providing opportunities for self-determination increases intrinsic motivation andself-determined extrinsic motivation, which inturn produce beneficial outcomes. Self-deter-

542 Canadian Psychology / Psychologie Canadienne, 1989, 30:3

mined elderly people should have higher levelsof intrinsic and self-determined extrinsic motiva-tion towards the activities of daily living and mayengage in such activities more frequently andwith more zest, leading them to derive moresatisfaction and meaning from their performance.

Apart from self-determination, perceptions ofcompetence and self-efficacy (Bandura, 1977)are also important. For example, positive compe-tence feedback (e.g., praise, success) enhancesintrinsic motivation (e.g., Blanck, Reiss, & Jack-son, 1984; Sansone, 1986; Vallerand & Reid,1984, 1988), and the experience of self-efficacyis associated with positive outcomes in the el-derly (Holohan & Holohan, 1987a, b; Woodward& Wallston, 1987). In fact, research on youngadults has revealed a causal sequence in whichpositive competence feedback and self-efficacyexert their effects on adjustment and well-beingthrough their effects on motivation (Blais et al.,1988; Pelletier, Briere, Blais & Vallerand, 1988).However, the competence feedback must begiven in a context of self-determination, other-wise it will be perceived as controlling and non-self-determined extrinsic motivation will beenhanced at the expense of extrinsic motivation(Fisher, 1978; Ryan, 1982). Thus, congratulatingnursing home residents for their initiatives inrestructuring leisure activities should promotefeelings of competence which should increaseintrinsic motivation. On the other hand, continu-ally telling residents that they are doing goodwork because their initiatives serve to reduce thestaff workload could eventually lead to feelingsof being controlled, which would reduce intrinsicmotivation. Eventually, nonself-determined ex-trinsic motivation may increase and residentsmay not engage in such activities unless proddedby the staff. Similarly, negative competence feed-back decreases intrinsic motivation (Vallerand &Reid, 1984) and eventually leads to amotivationand withdrawal (Boggiano & Barrett, 1985;Peterson & Seligman, 1984).

Although, much of the research to date hasfocused on the situational factors that affect mo-tivation, a more recent concern has been withrelatively stable individual differences in motiva-tional styles or orientations (Connell & Ryan,1986; Deci & Ryan, 1985b; 1987; Harter, 1981;Vallerand et al., in press). Emerging findings in-dicate that motivational styles are associated withsimilar consequences (Connell & Ryan, 1986;Deci & Ryan, 1985b; Grolnick & Ryan, 1987;

Vallerand & Bissonnette, 1988; Vallerand et al.,in press). The individual's habitual motivationalstyle is an important factor in the regulation ofbehaviour in life domains as diverse as education(Vallerand et al., in press), interpersonal relation-ships (Blais et al., 1988), and sports (Pelletieret al., 1988). Research on motivational styles hasonly recently begun, and little is known abouttheir stability or sensitivity to situational condi-tions. However, recent research revealed that mo-tivational styles in the education domain showrelatively high test/retest reliability (Vallerandet al., in press) and that motivation towardsschool in September is a strong predictor of drop-out rate in a compulsory course at the end of theterm (Vallerand & Bissonnette, 1988). Thesefindings suggest some stability in motivationalorientations. Broad cross-situational motiva-tional tendencies may be more stable than do-main-specific tendencies. One might also expectthe physical and social environments to havelong-term effects on motivational tendencies.

Findings From An On-Going ResearchProgram on Motivation in the Elderly

The following studies on motivation in theelderly had two purposes. One was to furtherunderstanding of the nature of motivation in theelderly via application of Deci and Ryan's theo-retical framework. The second purpose was toinitiate a research program that should eventuallybe useful in improving the lives of elderly people.For both, a necessary starting point was to de-velop reliable measures of the different kinds ofmotivation in the elderly. A second step was todetermine whether the four kinds of motivationdisplay a pattern of intercorrelations that is con-sistent with the theory. A third step was to see ifthe four kinds of motivation are related to otherimportant aspects of the lives of elderly people(see Vallerand & O'Connor, 1988, for a moredetailed presentation of the scale).

Development of the Motivation in the ElderlyScale (MES)

To develop a measure of broad cross-situa-tional motivational tendencies items from a vari-ety of life domains were required. Therefore, thefirst task was to determine the life domains thatare important to the elderly. A number of domainshave been discussed in the literature (Belsky,1984; Newman & Newman, 1984; Smyer &

Motivation in the Elderly 543

Gatz, 1983), from which a list of 23 domains wascompiled. Then, 130 elderly (94 women and 36men, with a mean age of 76.3 years) from nursinghomes, hospitals, private residences, and fromlow-cost public housing, were asked to rate theimportance of each of the 23 domains. The fol-lowing six domains received mean ratings of atleast seven on a scale of one to nine, and weretherefore used to develop the MES: health, reli-gion, biological needs, interpersonal relations,current events, and recreation. These were the sixmost important domains for both men and women,and for elderly living in different settings.

The next step was to specify importantbehaviours/situations within each domain. Tothis end, 42 elderly and six nursing home staffwere asked to nominate important situationswithin each of the six life domains. A variety ofsituations were identified, and for each domainthe two most commonly nominated situationswere selected for inclusion as questions in theMES (e.g., "Why do you go to church?"). Aswell, a general question for each domain wasadded (e.g., "In general, why do you practise yourreligion?"), for a total of three questions fromeach of the six life domains.

Because the goal was to develop a measure offour different motivational tendencies, eachquestion involved rating the truthfulness of fourpossible answers, corresponding to the four kindsof motivation. For example, the question "Whydo you go to church?" involved rating the truth-fulness of the following statements: 1) "I wouldlike to go to church, but I don't have the motiva-tion to do so" (AM); 2) "Because it gives mecourage for the days ahead" (NSDEM); 3) "Be-cause it brings me closer to God" (SDEM);4) "Because I like to reflect on the sermon" (IM).Conceptually similar statements were designedfor the four kinds of motivation for each of the 18questions—for a total of 72 items.

Two hundred and one French-Canadian el-derly (151 women and 50 men, with a mean ageof 77 years) were then asked to complete theMES. Subjects were randomly chosen from nurs-ing homes (n=101), private residences (n=50),and low-cost public housing (n=50). Subjectswere also asked to complete measures of self-es-teem, depression, life satisfaction, and meaningin life. A total score for each subject on each ofthe four kinds of motivation was computed. Clearand theoretically meaningful patterns or correla-tions emerged among the four types of motiva-

tion as well as between the different kinds ofmotivation and the other variables. However, thereliabilities of the four motivational scales weremoderate at best (the alphas ranged from .54 to .75),and item analyses did not reveal subsets of itemsthat were themselves more reliable or useful.

We therefore decided to modify the MES. Thesame three questions from each of the six lifedomains were retained, but the form of the fourresponses to each question was changed. As itwas, for each kind of motivation subjects ratedthe truthfulness of reasons suggested by the ex-perimenter (e.g., for NSDEM: "Why do you goto church?" "Because it gives me courage for thedays ahead;" "Why do you see members of yourfamily?" "Because they are nice to me"). Perhapsthe reliabilities were low because the particularreasons suggested in the answers were not whatsubjects had in mind; i.e., a subject may havebeen high on a given kind of motivation, but notfor the reason suggested. Therefore, to bypassthis source of variation the same four responses(corresponding to the four kinds of motivation)were used for all 18 questions (as in the Attribu-tional Style Questionnaire of Seligman, Abram-son, Semmel, & von Baeyer, 1979). The fourresponses selected were as follows: 1) "I don'tknow, I don't see what it does for me" (AM);

2) "Because I am supposed to do it" (NSDEM);3) "1 choose to do it for my own good" (SDEM);and 4) "For the pleasure of doing it" (IM). Thesestatements are example-free and may thereforebe more reliable and sensitive measures of thedifferent kinds of motivation .

One hundred seventy six French-Canadiannursing home residents (146 women and 30 men,with a mean age of 81.6 years) were then askedto complete the revised MES. The questionnairewas administered interview-style by trained re-search assistants. The reliabilities for the fourmotivation scales (see Table 1) were consider-ably higher (alphas ranged from .88 to .89), andwere quite high in light of the fact that the ques-tions tapped six life domains. Furthermore, thereliabilities of the four kinds of motivation foreach of the six life domain subscales were alsoquite high, indicating that motivation in theelderly can be examined within each domain.

An examination of the means (see Table 1)revealed that self-determined extrinsic and intrinsic

These are English translations; a copy of the Frenchstatements used or the questionnaire (MES) can be obtainedfrom the first author.

544 Canadian Psychology / Psychologie Canadienne, 1989,30:3

TABLE 1Total Scores and Internal Consistencies of the

Four Motivational Scales

AM NSDEM SDEM IM

Males 30.6Females 23.4Alpha .89

46.839.6.89

93.6102.6.89

77.488.2.88

Note: AM: amotivation; NSDEM: nonself-determinedextrinsic motivation; SDEM: self-determined extrinsicmotivation; IM: intrinsic motivation.

motivation were the most important forms ofmotivation reported by the elderly subjects. Non-self-determined extrinsic motivation and amotiva-tion followed in order. Females reported higherlevels of intrinsic and self-determined extrinsicmotivation, and males reported more nonself-de-termined extrinsic motivation and amotivation.Although these gender differences could stemfrom a variety of factors, they are interestingbecause similar results have been obtained instudies on the motivational styles of high schooland college students both in Canada and theUnited States (Connell & Ryan, 1986; Vallerandet al., in press) as well as in studies on perceivedcontrol in the elderly (Reker, Peacock, & Wong,1987).

The pattern of intercorrelations among the fourkinds of motivation (see Table 2) was generallyconsistent with the predictions of Deci & Ryan(1985a). The correlations indicate a continuumfrom Amotivation, to NonSelf-Determined Ex-trinsic Motivation, to Self-Determined ExtrinsicMotivation, to Intrinsic Motivation. Adjacentscales on this continuum show moderate positiveintercorrelations, whereas scales farther apartshow stronger negative intercorrelations. Thesimplex structure proposed by Deci & Ryan(1985a) is therefore supported.

There was also a significant positive relation-ship between Intrinsic Motivation and self-ratedhealth (M - .21, p < .01), but no relationshipbetween health and the other kinds of motivation.None of the correlations between the four kindsof motivation and age was significant (see Table 2).

Relations Between Motivation andPsychological and Health Variables

The subjects who completed the revised MEShad also been asked to complete one or more of

TABLE 2Correlations Among the Four MotivationScales, and Between the Four Kinds of

Motivation and Age, and Self-Rated Health

NSDEMSDEMIMAgeSelf-RatedHealth

AM

.28C

-.39C

-.57C

-.05

-.08

NSDEM

-.15 a

-.43°-.05

-.11

SDEM

.58C

.01

.04

IM

.03

.21b

Note: AM: amotivation; NSDEM: nonself-determinedextrinsic motivation; SDEM: self-determined extrinsicmotivation; IM: intrinsic motivation, "a" indicatesp < .05; "b" indicates p < .01; "c" indicates p < .001.

the following measures: a French translation ofRosenberg's Self-Esteem scale (Vallerand,1987); a French translation (Bourque & Beau-dette, 1982) of three items from the Beck Depres-sion Inventory that are known to be homoge-neous and valid (Kane & Kane, 1981, p. 117);and a French cross-cultural validation form of theDiener's Satisfaction With Life scale (Blais,Vallerand, Pelletier, & Briere, 1989). Four otherquestions were adapted from Reker and Peacock(1981) to tap Meaning in Life. Subjects were alsoasked to rate their health on a scale ranging fromvery poor to very good. All scales were found todisplay adequate internal consistency (alphasranged from .78 to .87).

Because perceptions of self-determination arehypothesized to affect motivation in the elderly,subjects were also asked to complete two addi-tional relevant measures: 1) Wolk and Telleen's(1976) measure of perceived residential con-straint; and 2) the two central items of the Locusof Desired Control Scale (Reid, Haas, & Hawk-ings, 1977): "How important is it for you to beable to decide on what your everyday behaviorsare going to be?" and "How often can you your-self decide what your everyday behaviors aregoing to be?" The two ratings are multiplied andthe resulting score indicates the extent to whichindividuals can exercise control over everydaybehaviors for which choice is desired.

Finally, the social workers in charge of leisureactivities at each of the nursing homes, who werewell acquainted with the residents, were askedgeneral questions about the mental and physical

Motivation in the Elderly 545

health of the residents. The questions formedthree scales assessing 1) "psychological status"("To what extent has the person been: mentallyalert? autonomous? psychologically stable?");2) the degree of "activeness" in everyday behav-iors; and 3) a general evaluation of health. Thealpha values ranged from .76 to .90.

The correlations between the four kinds ofmotivation and these other variables were ex-pected to correspond to the continuum proposedby Deci & Ryan (1985a). That is, health, locus ofdesired control, life satisfaction, meaning in life,self-esteem, health, psychological status, and ac-tiveness were expected to show the strongestpositive correlations wtih Intrinsic Motivation,and the strongest negative correlations withAmotivation. Depression and perceived residen-tial constraint were expected to show an inversepattern of correlations with the motivation vari-ables.

The partial correlations between the four typesof motivation and the other variables, controlling

for self-rated health, appear in Table 3. The cor-relations were generally in accord with the pre-dictions. Meaning in Life, Life Satisfaction andSelf-Esteem showed the clearest patterns: thestrongest negative correlations were withAmotivation; there were weaker but still negativecorrelations with NonSelf-Determined ExtrinsicMotivation; there were moderately positive cor-relations with Self-Determined Extrinsic Moti-vation; and the strongest positive correlationswere with Intrinsic Motivation. For Depression,the highest positive correlation was withAmotivation (;•= .43, p<.00l), and the highestnegative correlation was with Self DeterminedExtrinsic Motivation (/— - .34, p<.04). The corre-lation between Depression and Intrinsic Motiva-tion was also significant (r= - .3 I ,p< .00I ) , butslightly lower than that of Self-Determined Ex-trinsic Motivation.

The correlations between the motivation vari-ables and Perceived Residential Constraint andLocus of Desired Control indicate that elderly

TABLE 3Correlations Between the Four Kinds of Motivation and the Psychological and Health Variables

Residential* Constraint(n = 143)

Locus of Desired* Control(n = 146)

Self-Esteem*(n= 146)

Depression*(n = 146)

Life Satisfaction*(n= 174)

Meaning in Life*(n = 145)

General Health(n = 80)

Psychological Status(n = 80)

Activeness(n = 80)

AM

.23"

- .42"

- .27"

.43C

- .33 C

- . 45"

- .28"

- .12

-.17

NSDEM

.31C

- .30 c

- .25C

.37C

- .14 a

- .34"

- .41 C

-,36C

- .32"

SDEM

-.51 C

.50c

.39C

-.34C

.16a

.47C

.35C

.35C

.22a

IM

-.42C

.45C

.44C

- . 31 C

.19a

.51C

.38C

.34C

.18

Note: * indicates partial correlations controlling for self-rated health; AM: amotivation; NSDEM: nonself-determinedextrinsic motivation; SDEM: self-determined extrinsic motivation; IM: intrinsic motivation, "a" indicates p < .05; "b"indicates p < .01; "c" indicates p < .001.

546 Canadian Psychology / Psychologie Canadienne, 1989,30:3

who reported having control over desired activi-ties reported less Amotivation (r= -.52, p=.00l)and more Self-Determined Extrinsic Motivation(r= .50, p<.001). Similarly, elderly who per-ceived more residential constraint reported lessSelf-Determined Extrinsic Motivation (r= -.42,p<.001). Intrinsic Motivation was less stronglyrelated to these variables than was Self-Deter-mined Extrinsic Motivation.

Finally, the Pearson correlations between thefour kinds of motivation and the social workers'ratings were also generally in accord with predic-tors (see Table 3). Elderly people higher on In-trinsic and Self-Determined Extrinsic Motivationreceived higher ratings on General Health, Psy-chological Status, and Activeness, whereas el-derly people higher on Amotivation andNonSelf-Determined Extrinsic Motivation re-ceived lower ratings on these variables.

Conclusions

The present findings indicate that four kindsof broad, cross-situational motivational tenden-cies in elderly people can be reliably measured;that the intercorrelations between the four kindsof motivation are in accord with the simplexstructure proposed by Deci & Ryan (1985a); andthat the four kinds of motivation are related toother important aspects of the lives of elderlypeople in a theoretically meaningful manner. Theframework proposed by Deci & Ryan (1985a)based on research with young people thus ap-pears quite applicable to the motivation behindeveryday behaviours in the elderly.

One interesting finding was that locus of de-sired control and perceived residential constraintwere correlated with the motivation variables,which were in turn associated with the psycho-logical and health variables. This provides tenta-tive support for the causal sequence proposed byDeci and Ryan (1985a): perceived self-determi-nation affects motivation, which in turn affects avariety of psychological variables. However, thefindings are merely suggestive because they arecorrelational and because the variables weremeasured at only one point in time. It is alsopossible that changes in health status affect mo-tivation and control. Longitudinal studies em-ploying causal modelling are therefore requiredto determine the correct causal sequence. Itwould also seem important to examine the actualamount of self-determination in living environ-

ments in relation to motivation and other vari-ables.

One unexpected finding was that depression,perceived residential constraint and locus of de-sired control showed stronger correlations withself-determined extrinsic motivation than withintrinsic motivation. This was unexpected be-cause research on younger people has found thatintrinsic motivation is the variable most stronglyassociated with positive consequences. Perhapsself-determined extrinsic motivation is more im-portant among the elderly, or perhaps it is onlymore important among people living in nursinghomes—environments in which self-determina-tion is a key factor. Another possibility is thatsome activities of daily living may not be veryenjoyable or intrinsically motivating, and thatself-determined extrinsic motivation may be themore adaptive form of motivation for these activ-ities. Finally, it is possible that intrinsic motiva-tion is more important for some domains whileself-determined extrinsic motivation is moreadaptive for other domains. A more differentiatedapproach to motivation and its consequenceswithin life domains may be more appropriate(Lachman, 1986 and Rodin, 1987 made similarsuggestions for research on control). Because thefour motivational subscales are reliable withineach of the six life domains, it appears that the MEScould be used in such a differentiated approach.

While the above findings are encouraging,several directions are open for further investiga-tion. First, the findings must be replicated onnon-institutionalized populations. One couldalso examine whether there are normativechanges in the nature of motivation with age, andwhether individual differences in motivation arerelated to differential patterns of aging. Onecould assess how life events (e.g., retirement, thedeath of loved ones, changing social interactions,declining personal competence) and living envi-ronments (e.g., regular community housing, andhigh and low self-determination nursing homes)affect the four kinds of motivation. One couldexamine the consequences of the four kinds ofmotivation for other aspects of the lives of elderlypeople. One could examine the extent to whichmotivational changes mediate the relationshipbetween life events and living environments onthe one hand, and adaptation and well-being onthe other. One could ascertain the impact of mo-tivational changes in one life domain on motiva-tion in other domains. It would also appear

Motivation in the Elderly 547

important to examine the stability of the differentforms of motivation in elderly people. Howquickly does the motivation behind everydaybehaviours change? How quickly do life eventsand living environments exert their effects onmotivational tendencies?

The present framework may also extend pre-vious research on control in the elderly. For ex-ample, Perlmuter, Monty, and Chan (1986)propose that choice increases perceived control,which in turn enhances motivation and perfor-mance. The present findings suggest the useful-ness of examining different forms of motivationwithin this context. Lachman (1986) reports arelationship between locus of control and intel-lectual functioning, and suggests there may be areciprocal causal relationship between the two.However, the individual's motivational orienta-tion may be a mediating variable. Control mayenhance the more self-determined forms of mo-tivation for intellectual activities, the per-formance of which is beneficial to cognitivefunctioning. Conversely, the performance of in-tellectual activities may produce a sense of com-petence and intrinsic reward which in turnenhances motivation and control. Finally, Piperand Langer (1986) report how the physical andsocial environments of elderly people decreasecontrol and encourage mindlessness, which has avariety of negative consequences. One negativeconsequence could be detrimental effects on mo-tivation. Similarly, interventions that enhancemindfulness may be successful if they lead to asense of meaning, competence, and self-determi-nation, which in turn enhance motivation. Onemight also expect the different kinds of motiva-tion to be associated with different kinds of mind-fulness/mindlessness.

A number of practical applications for enhanc-ing the lives of elderly people can be derived fromthe present findings. For example, individualswho work with elderly people should pay closeattention to the factors that affect motivation.Providing opportunities for autonomy and choiceare most strongly recommended. Self-determina-tion is the necessary condition for enhancing themore beneficial forms of motivation. "Self-deter-mination allows one to try out new activities, toexplore new spaces, and to experience gratifica-tion from the exploration" (Deci, 1980, p. 44).Living environments that provide opportunitiesfor choice are more likely to instill feelings ofself-determination among residents (see Moos,

1981; Monty & Perlmuter, 1987; Rodin, 1987;Schulz, 1976; Wolk & Telleen, 1976), whichshould eventually enhance intrinsic and self-de-termined extrinsic motivation. Attempts to in-crease self-determination are most likely to bebeneficial if they are directed at life domains thatare considered important by the elderly (e.g.,Lachman, 1986; Rodin, 1987). Such attemptsshould also address the amount of choice or con-trol desired by particular individuals becausethere is much variation in preferences for controlamong the elderly and too much choice or controlmay be overwhelming and detrimental(Lachman, 1986; Rodin, 1986).

A second suggested application is that elderlypeople should be supportecNn their attempts toengage in potentially enjoyable>qptimally chal-lenging activities of their own choosing. Partici-pation in such activities should enhance morepositive forms of motivation and their associatedconsequences. This suggestion is in accord withGlasser's (1976) positive addiction therapy,which encourages depressed individuals toengage in potentially rewarding everydaybehaviours.

Although many researchers and practitionersmay be aware of the importance of self-determination and participation in everydaybehaviours, the present findings suggest a muchless familiar caution in dealing with the elderly:very close attention should be paid to the natureof any encouragement to participate in the activ-ities of daily life. If elderly people feel compelledby the others to engage in particular activities,their intrinsic or self-determined extrinsic moti-vation towards these activities may actually beimpaired. On the other hand, if the social climateof the residence encourages a sense of self-deter-mination, then these forms of motivation may beenhanced. Clearly, a considerable degree of inter-personal knowledge and skill is required for anyattempt to enhance motivation and well-being.Further research could focus on the developmentof strategies for encouraging participation in theactivities of daily living that instill feelings ofchoice and self-determination.

Finally, some reviewers have remarked thatthe social psychology of aging, as it has beenpractised within the multidisciplinary field ofsocial gerontology, is incomplete and not suffi-ciently "social psychological" (Blank, 1982;Schulz, 1982). Sociologists have been the maincontributors, and theoretical and methodological

548 Canadian Psychology / Psychologie Canadienne, 1989, 30:3

perspectives from experimental social psychol-ogy have not been used (Schulz, 1982, p. 510).The theoretical framework and research direc-tions suggested in this paper represent one step

towards reversing this trend, and should be espe-cially useful because motivation is at the core ofmany social, personality, and biological changes.

RESUME

Meme si de plus en plus d'interet est accorde a la condition des personnes agees, nous savonstres peu de choses en ce qui concerne la motivation de celles-ci face a leurs activites de tousles jours. Dans cet article nous proposons l'adoption d'un modele theorique de la motivationqui a demontre son utilite en recherche avec de jeunes adultes. Ce modele theorique (Deci& Ryan, 1985a) propose l'existence de quatre types de motivation (intrinseque, extrinsequeautodeterminee, extrinseque non-autodeterminee et amotivation). Qui plus est, on proposeque ces types de motivation sont relies de fagon specifique avec des consequences psycho-logiques et physiques. Apres avoir decrit la theorie, nous presentons certains resultats d'unprogamme de recherche sur la motivation chez les personnes agees presentement en cours.On demontre que les quatre types de motivation peuvent etre mesures avec validite et fideliteet qu'ils sont relies avec d'importants aspects de la vie des personnes agees de fa?onconforme avec la theorie. Des suggestions sont faites en ce qui concerne les recherchesfutures ainsi que des applications potentielles.

ReferencesAbramson, L.Y., Seligman, M.E.P., & Teasdale, J.D. (1978).

Learned helplessness in humans: Critique and reformula-tion. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 87,49—74.

Allan, C , & Brotman, H. (1981). Charthook on aging inAmerica. Washington, DC. White House Conference onAging.

Bakes, M.M., & Bakes, P.B. (1986). The psychology ofcontrol and aging. Hi llsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theoryof behavioral change. Psychological Review.84,191-215.

Belsky, J.A. (1984). The psychology of aging: Theory,research, and practice. Monterey, CA: Brooks-Cole.

Binstock, H., & Shanas, H. (Eds.) (1985). Handbook of agingand the social sciences. New York: Van Nostrand.

Birren, J.E., & Schaie, K.W. (Eds.) (1985). Handbook of thepsychology of aging. New York: Van Nostrand.

Blais, M.R., Sabourin, S., Boucher, C , & Vallerand, R.J.(1988). Toward a motivational model of couple happiness.Manuscript submitted for publication.

Blais, M.R., Vallerand, R.J., Pelletier, L.G., & Briere, N.(1989). Validation trans-culturelle de I'Echelle de Sa-tisfaction de Vie. Canadian Journal of Behavioral Sci-ences, 21,210-233.

Blank, T.O. (1982). The incomplete social psychology ofaging: A psychologist's perspective. International Journalof Aging and Human Development, 14,307—317.

Blanck, P.D., Reis, H.T., & Jackson, L. (1984). The effectsof verbal reinforcement on intrinsic motivation for sex-linked tasks. Sex Roles, 70,369-387.

Boggiano, A.K., & Barrett, M. (1985). Performance andmotivational deficits of helplessness: The role of motiva-tional orientations. Journal of Personality and SocialPsychology,49,1753-1761.

Bourque, & Beaudette, D. (1982). Etude psychometrique duquestionnaire de depression de Beck aupres d'un£chantillon d'6tudiants universitaires francophones. RevueCanadienne des Sciences du Contportement, 14,211—218.

Cicirelli, V.G. (1987). Locus of control and patient role

adjustment of the elderly in acute-care hospitals. Psychol-ogy and Aging,2, 138—143.

Connell, J.P., & Ryan, R.M. (1986). Autonomy in the class-room: A theory and assessment of children's self-regula-tory styles in the academic domain. Unpublishedmanuscript. University of Rochester, Rochester, NY.

Deci, E.L. (1971). Effects of externally mediated rewards onintrinsic motivation. Journal of Personality and SocialPsychology, 18, 105-115.

Deci, E.L. (1975). Intrinsic motivation. New York: Plenum.Deci, E.L. (1980). The psychology of self-determination.

Lexington, MASS: DC Heath.Deci, E.L., & Ryan, R.M. (1980). The empirical exploration

of intrinsic motivational processes. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.),Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 13)

(pp. 39-80). New York: Academic Press.Deci, E.L., & Ryan, R.M. (1985a). Intrinsic motivation and

self-determination in human behavior. New York: Ple-num.

Deci, E.L., & Ryan, R.M. (1985b). The General CausalityOrientations Scale: Self-determination in personality.Journal of Research in Personality, 19, 109-134.

Deci, E.L., & Ryan, R.M. (1987). The support of autonomyand the control of behavior. Journal of Personality andSocial Psychology, 53,1024-1037.

Die, A.H., Seelbach, W.C., & Sherman, G.D. (1987).Achievement motivation, achieving styles, and morale inthe elderly. Psychology and Aging, 2,407-408.

Eisdorfer, C , & Cohen, D. (1980). The issue of biological andpsychological benefits. In E.F. Borgatta & N.G. McC-luskey (Eds.), Aging and society: Current research andpolicy perspectives (pp. 49-70). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Fisher, C.F. (1978). The effects of personal control, compe-tence and extrinsic reward systems on intrinsic motivation.Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 21,

273-288.Freud, S. (1962). The ego and the id. New York: Norton

(originally published in 1923).

Motivation in the Elderly 549

Gauthier, H., & Duchesne, L. (1986). Les personnes ageesau Quebec: Statistiques demographiques. Quebec: Lespublications du Quebec.

Glasser, W. (1976). Positive addiction. New York: Harper &Row.

Grolnick, W.S., & Ryan, R.M. (1987). Autonomy inchildren's learning: An experimental and individual differ-ence investigation. Journal of Personality and SocialPsychology, 52,890-898.

Haemmerlie, F.M., & Montgomery, R.L. (1987). Self-percep-tion theory, salience or behavior, and a control-enhancingprogram for the elderly. Journal of Social and ClinicalPsychology, 5,313-329.

Haiter, S. (1981). A new self-report scale of intrinsic versusextrinsic orientation in the classroom: Motivational andinformational components. Developmental Psychology,/ 7,300-312.

Holahan, C.K., & Holahan, C.J. (1987a). Self-efficacy, socialsupport, and depression in aging: A longitudinal analysis.Journal of Gerontology, 42,65-68.

Holahan, C.K., & Holahan, C.J. (1987b). Life stress, hassles,and self-efficacy in aging: A replication and extension.Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 17,574-592.

Jameton, A. (1988). In the borderlands of autonomy: Respon-sibility in long-term facilities. The Gerontologist, 28,18-23.

Kane, R.A., & Kane, R.L. (1981). Assessing the elderly.Toronto: Lexington.

Kleiber, D.A., & Maehr, M.L. (1985) (Eds.), Advances inmotivation and achievement: Motivation and adulthood(Vol. 4). London: JAI Press.

Kobasa, S.C. (1979). Stressful life events, personality andhealth: An inquiry into hardiness. Journal of Personalityand Social Psychology, 37, 1—11.

Kruglanski, A.W. (1978). Endogenous attribution and intrin-sic motivation. In M.R. Lepper & D. Greene (Eds.), Thehidden costs of reward: New perspectives on the psychol-ogy of human motivation (pp. 85—107). Hillsdale, NJ:Erlbaum.

Lachman, M.E. (1986). Personal control in later life: Stability,change, and cognitive correlates. In M.M. Baltes &P.B. Baltes (Eds.), The psychology of control and aging(pp. 207-236). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Langer, E.J., & Rodin, J. (1976). The effects of choice andenhanced personal responsibility for the aged: A fieldexperiment in an institutional setting. Journal of Person-ality and Social Psychology. 34, 191-198.

Maddi, S., & Kobasa, S.C. (1982). Intrinsic motivation andhealth. In H.I. Day (Ed.), Intrinsic motivation, play, andaesthetics (pp. 229-321). New York: Academic Press.

Maehr, M.L., & Kleiber, D.A. (1981). The graying of achieve-ment motivation. American Psychologist, 36,787-793.

Monty, R.A., & Perlmuter, L.C. (1987). Choice, control, andmotivation in the young and aged. In M.L. Maehr &D.A. Kleiber (Eds.), Advances in motivation and achieve-ment: Enhancing motivation (vol. 5) (pp. 99-122). Green-wich, CT: JAI Press.

Moos, R.H. (1981). Environmental choice and control incommunity care settings for older people. Journal ofApplied Social Psychology, 11,23^3.

Newman, B.M., & Newman, P.R. (1984). Developmentthrough life: A psychosocial approach. Homewood, IL:Dorsey Press.

Pelletier, L.G., Briere, N.M., Blais, M.R., & Vallerand, R.J.(1988). Persisting vs dropping out: A test of Deci and

Ryan's theory. Canadian Psychology, 29(2a), 600. (ab-stract).

Perlmuter, L.C, Monty, R.A., & Chan, F. (1986). Choice,control, and cognitive functioning. In M.M. Baltes & P.B.Baltes (Eds.), The psychology of control and aging(pp. 207-236). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Peterson, C , & Seligman, M.E.P. (1984). Causal explana-tions as a risk factor for depression: Theory and evidence.Psychological Review. 94,347—374.

Petri. H.L. (1981). Motivation: Theory and Research. Bel-mont, CA: Wadsworth.

Piper, A.I., & Langer, E.J. (1986). Aging and mindful control.In M.M. Baltes & P.B. Baltes (Eds.), The psychology ofcontrol and aging (pp. 207-236). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Reid, D.W., Haas, G., & Hawkings, D. (1977). Locus ofdesired control and positive self-concept of the elderly.Journal of Gerontology. 32, A4\—450.

Reker, G.T., & Peacock, E.J. (1981). The Life Attitude Pro-file: A multidimensional instrument for assessing attitudestoward life. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 13,264-273.

Reker, G.T., Peacock, E.J., & Wong, P.T.P. (1987). Meaningand purpose in life and well-being: A life-span perspective.Journal of Gerontology, 42,44-49.

Reker, G.T., & Wong, P.T.P. (1988). Aging as an individualprocess: Toward a theory of personal meaning. InJ.E. Birren, & V.L. Bengtson (Eds.), Emergent theories ofaging (pp. 214-246). New York: Springer.

Rodin, J. (1986). Health, control, and aging. In M.M. Baltes,& P.B. Baltes (Eds.), The psychology of control and aging(pp. 139-165). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Rodin, J. (1987). Personal control through the life course. InR.P. Abeles (Ed.), Life-span perspectives and social psy-chology (pp. 103-119). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Rodin, J., & Langer, E.J. (1977). Long-term effects of acontrol-relevant intervention with the institutionalizedaged. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35,897-902.

Ryan, R.M. (1982). Control and information in the intrapersonal sphere: An extension of cognitive evaluation theory.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43, 450-

461.Ryan, R.M., Connell, J.P., & Deci, E.L. (1985). A motiva-

tional analysis of self-determination and self-regulation ineducation. In C. Ames & R.E. Ames (Eds.), Research onmotivation in education: The classroom milieu (pp. 13—51). New York: Academic Press.

Ryan, R.M., Connell, J.P., & Grolnick, W.S. (in press). Whenachievement is not intrinsically motivated: A theory andassessment of self-regulation in school. In A.K. Boggiano& T.S. Pittman (Eds.), Achievement and motivation: Asocial-developmental perspective. Cambridge: CambridgeUniversity Press.

Sansone, C. (1986). A question of competence: The effects ofcompetence and task feedback on intrinsic interest. Jour-nal of Personality and Social Psychology, 5 / , 918—931.

Schaie, K.W., & Willis, S.L. (1986). Adult development andaging. Boston: Little, Brown, & Co.

Schulz, R. (1976). Effects of control and predictability on thephysical and psychological well-being of the institutional-ized aged. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,33,563-573.

Schulz, R. (1982). Aging, health, and theoretical social ger-ontology: Where are we and where should we go? InJ.R. Eiser (Ed.), Social psychology and behavioral medi-

550 Canadian Psychology / Psychologie Canadienne, 1989,30:3

cine (pp. 509-525). New York: John Wiley.Seligman, M.E.P., Abramson, L.Y., Semmel, A., & von

Bayer, (1979). Depressive attributional style. Journal ofAbnormal Psychology, 88,242-247.

Skinner, B.F. (1953). Science and human behavior. NewYork: Macmillan.

Smyer, M.A., & Gatz, M. (Eds.). (1983). Mental health andaging: Programs and evaluations. Beverly Hills, CA:Sage.

Statistiques Canada (1985). La conjoncture demographique:Rapport sur I'etat de la population du Canada 1983. ByJean Dumas, Ottawa, cat. #91-209.

Steinkamp, M.W., & Kelly, J.R. (1985). Relationships amongmotivational orientation, level of leisure activity, and lifesatisfaction in older men and women. The Journal ofPsychology, 119,509-520.

Swann, W.B., & Pittman, T.S. (1977). Initiating play activityof children: The moderating influence of verbal cues onintrinsic motivation. Child Development, 48,1128 1132.

Thompson, L.W., & Nowlin, J.B. (1973). Relation of in-creased attention to central and autonomic nervous systemstates. In L. Jarvik, C. Eisdorfer, & J. Blum (Eds.), Intel-lectual functioning in adults: Psychological and biologicalinfluences (pp. 107-123). New York: Springer.

Vallerand, R.J. (1987). Traduction de I'Echelle d'Estime deSoi de Rosenberg. Echelle d'Estime de Soi and data on thescale, both unpublished, Laboratoire de psychologiesociale, Universite du Quebec a Montreal.

Vallerand, R.J., & Bissonnette, R. (1988). On the predictiveeffects of intrinsic, extrinsic, and amotivational styles onbehavior: A prospective study. Manuscript submitted forpublication.

Vallerand, R.J., Blais, M.R., Briere, N.M., & Pelletier, L.G.(in press). Construction et validation de I'Echelle de Moti-vation en Education (EME). Canadian Journal ofBehavioural Science.

Vallerand, R.J., & O'Connor, B.P. (1988). The developmentof the Motivation in the Elderly Scale. Manuscript submit-ted for publication.

Vallerand, R.J., & Reid, G. (1984). On the causal effects ofperceived competence on intrinsic motivation: A test ofcognitive evaluation theory. Journal of Sport Psychology,6,94-102.

Vallerand, R.J., & Reid, G. (1988). On the relative effects ofpositive and negative verbal feedback on males andfemales' intrinsic motivation. Canadian Journal ofBehavioural Sciences, 20,239-250.

Veroff, J., & Veroff, J.B. (1980). Social incentives: A life-span developmental approach. New York: AcademicPress.

Walker, J., & Hertzog, C. (1975). Aging, brain function, andbehavior. In D.S. Woodruff & J.E. Birren (Eds.), Aging:Scientific perspectives and social issues (pp. 152—178).New York: D. Van Nostrand.

White, C.B., & Janson, P. (1986). Helplessness in institutionalsettings: Adaptation or latrogenic disease? In M.M. Baltes,& P.B. Baltes (Eds.), The psychology of control and aging(pp. 297-313). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Wigdor, B.T. (1980). Drives and motivations with aging. InJ.E. Birren & R.B. Sloane, (Eds.), Handbook and mentalhealth and aging (pp. 245-265). Englewood-Cliffs, NJ:Prentice-Hall.

Wolk, S., & Telleen, S. (1976). Psychological and socialcorrelates of life satisfaction as a function of residentialconstraint. Journal of Gerontology, 31,89—98.

Woodruff, D.S. (1975). A physiological perspective of thepsychology of aging. In D.S. Woodruff & J.E. Birren(Eds.), Aging: Scientific perspectives and social issues(pp. 179-198). New York: D. Van Nostrand.

Woodward, N.J., & Wallston, B.S. (1987). Age and healthcare beliefs: Self-efficacy as a mediator or low desire forcontrol. Psychology and Aging, 2, 3—8.

Zuckerman, M., Porac, J., Lathin, D., Smith, R., & Deci, E.L.(1978). On the importance of self-determination for intrin-sically motivated behavior. Personality and Social Psy-chology Bulletin, 4,443^46.