Monitoring Your Wetland - Dragonflies and Damselflies,...

Transcript of Monitoring Your Wetland - Dragonflies and Damselflies,...

a primer to site-level monitoring activities for volunteer coordinators

This publication is part of a Monitoring Your Wetland series available online in pdf format at:wetlandmonitoring.uwex.edu

yourMonitoring

Wetland

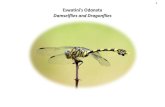

When at rest, the dragonfly keeps its

wings open and more perpen dicular to its body,

whereas the damselfly folds its wings behind its back or holds them at about a 45-degree angle to its body.

“

”

(Odonata)

. . . . . . . . . .

Dragonflies & Damselflies

If while walking through a wetland on a warm summer day, you notice only two insects besides the mosquito, there’s a good chance

one will be a butterfly and the other an odonate. Both are large, easy to recognize and often display eye-catching colors and patterns. While amateur entomologists often fall under the spell of soft-winged, nectar-feeding butterflies, some find the

ethereal beauty and nature of the odonate even more enchanting. With their long translucent wings, Odonata can hover, quickly accelerate in any direction and maneuver precisely to capture prey. And an odonate’s large compound eyes and grapple of slender legs allow it to deftly snatch moving prey from the air.

In Wisconsin, there are approximately 160 species of Odonata, including large conspicuous species such as the nearly four-inch-long blue-eyed swamp darner and tiny inconspicuous species such as the elfin skimmer, which measures just 0.8 inches long. The Odonata are divided into two very similar looking, but easily distinguished, suborders – dragonflies and damselflies. Damsel-flies tend to be more slender than dragonflies, but the two sub orders are probably

most easily distinguished from each other by their wings. When at rest, the dragonfly keeps its wings open and more perpendicular to its body, whereas the damselfly folds its wings behind its back or holds them at about a 45-degree angle to its body.

A great deal remains unknown about the distribution of and critical habitats for Odonata species in Wisconsin and there are few Odonata experts available to survey the state’s 72 counties. Volunteer monitors can help experts fill informational gaps and engage in a rewarding monitoring activity. Odonata readily capture the imagination of monitoring volunteers and many volunteers develop a hobby of photo graphing them.

familiar bluet damselflies

blue dasher dragonfly

EXPERTIS

E

RES

OURCES

HIGHHIGH

LOWLOW

About Dragonfly & Damselfly Surveys

Survey Participants

Odonata have a three-stage life cycle – an egg stage, larval stage and adult stage.

The presence of Odonata species in a wetland can be determined by identifying specimens in the larval or adult stages. Presence can also be detected by collecting and identifying exuviae – the larval exoskeletons Odonata leave behind when they become adults. Identifying adult Odonata is the easiest and most common method used for surveying. Even in the adult stage, identifying Odonata is difficult and volunteers who want to con tribute to a thorough wetland inventory of Odonata species or to state Odonata distribution data will need to make an ambitious effort to become familiar with species.

The most accessible volunteer wetland Odonata monitoring activity is the creation of an inventory of Odonata species. An Odonata species inventory can help monitoring

volunteers better characterize your wetland. Also, when inventory data collection is done well, the data can be submitted to state Odonata experts to help them under stand the distribution of species and their habitats throughout the state. Finally, you never know when a volunteer may discover something entirely new. Every two years or so, a volunteer

or naturalist will discover a species not yet documented in Wisconsin.

The information in the supplies and equipment, participant and methods sections of this publication is designed to help volunteers maximize detection and

accurate identification. This will ensure volunteer-collected data results in as complete an inventory as possible. It will also increase the likelihood that collected data will help Odonata experts better under stand Wisconsin Odonata species distribution.

Capturing, photographing and preparing samples is relatively easy, but identifying

Odonata down to species or even genus is difficult. In order to gather useful data, monitor-ing group members should be able to identify at least the most common species of Odonata likely to be present in your wetland. At the very least, the team leader should have at least one year’s experience in identifying Odonata and using the Wisconsin Odonata Survey database.

With more than 160 species of Odonata to identify, becoming competent in Odonata

identification will take time and effort. But volunteers can have a lot of fun observing and photographing Odonata, without knowing many species. When volunteers begin to get familiar with common Odonata species, they are reaching the point where they can contribute useful information. A really inspired Odonata monitoring volunteer might expand their con-tribution to Odonata research by cultivating a relationship with Wisconsin Odonata Survey experts, who sometimes recruit ambitious volun-teers to participate in their research projects.

Every two years or so, a volunteer or naturalist will discover a species not yet documented in Wisconsin.”

“

Monitoring Your Wetland – Dragonflies & Damselflies

2

There is no minimum or maximum num-ber of volunteers needed to conduct Odonata surveys in a wetland. The more eyes there are looking for Odonata in your wetland, the more

likely you are to detect the full spectrum of Odonata species using it. But even just one dedicated volunteer can gather valuable and useful data.

Volunteers can get by with

minimal supplies when monitoring

Odonata. Absolutely necessary

Odonata monitoring supplies

could probably be pared down

to a field guide, pencil and

notebook.

However, the addition

of a few basic pieces of equip ment

and supplies can greatly enhance

volunteers’ ability to detect and

identify a represen tative sample

of the species present within your

wetland. These might include

equipment and supplies that

enable volunteers to get a closer

look at specimens, such as an

insect net and waders for

capturing and a 10X loupe

magnifying glass for

inspecting captured Odonata.

Volunteers can capture Odonata

using an insect net with a hoop

measuring anywhere from

10 to 15 inches wide. Smaller

hooped nets are lighter, but

require more skill.

Then there are supplies for

identifying and documenting

specimens. In addition to a field

guide, pencil and notebook,

volunteers might want supplies

and equipment that allow them to

recruit the help of Odonata

experts in identifying specimens.

For novices just beginning to

learn to identify species the best

tool for this is a digital camera.

With a digital camera, volunteers

can send pictures to experts

for identification assistance.

Most popular point-and-shoot

digital cameras have macro

features sufficient for taking the

close-up pictures needed for

identification.

Volunteers with more advanced

identification skills might also

want supplies for preserving

specimens they recognize as

unusual, but cannot identify.

For specimen preservation,

volunteers will need, at a min-

imum, acetone for preservation

and envelopes in which to keep

preserved specimens. Glassine

envelopes, like the kind used

for stamps, are generally

preferred. You may also want a

laboratory pen designed to

resist solvents including

acetone. Writing identification

notes to include with your

specimen using solvent-resistant

ink will ensure that your notes

remain readable.

Supplies and Equipment

Common Whitetail

DRAGONFLIES

Four-spotted skimmer Dot-tailed whiteface (juvenile) Yellow-legged meadowhawk

Monitoring Your Wetland – Dragonflies & Damselflies

3

Surveying – When & Where

Capturing & Observing

The odonate spends only a small fraction of its life as a winged adult. An odonate might

live for as long as two years, but only spend four to six weeks of its life span as an adult. The season for surveying adult Odonata generally begins in late May and lasts until September. The greatest number of Odonata can be found in June and July, on sunny days when the

Volunteers can do two things to improve their ability to capture Odonata – get into

the water and learn to wield a net with great stealth. In wetlands where there is standing water, volunteers can come within reach of more Odonata if they pull on a pair of waders and slip into the water where Odonata cling to and hover around emer-gent vegetation.

Additionally, successful capture will require cunning maneuvers on the part of volunteers.

weather is warm or hot, and the winds are low.Although there are more Odonata in flight

in mid-summer, surveys conducted during other parts of the season are also important since the species currently in flight will change from month to month.

Even just one survey conducted at a site by a volunteer with strong identification skills can provide Odonata experts with useful information. But more frequent surveys are more likely to detect one of the unusual species that interest experts most, and to provide a more complete species inventory. The most complete surveys are conducted in the same area once every ten days to two weeks.

Volunteers will capture Odonata more easily if they approach perched Odonata slowly, conceal themselves behind vegetation and target Odonata that are facing away from them.

Once an odonate is captured, it can be removed from the net by hand. If a captured odonate is not needed as a sample and is handled carefully, it may be released back into the wetland after it has been identified or photographed.

More frequent surveys are more likely to detect one of the unusual species that experts are most interested in and to provide a more complete species inventory. ”

“

Ebony jewelwing damselfly

USF

WS

Monitoring Your Wetland – Dragonflies & Damselflies

4

Sampling

Once volunteers have developed relatively strong identification skills, they may begin

to recognize when they have captured some-thing unusual and worth sending as specimen sample to experts for identification.

When a captured odonate specimen is kept as a sample, the odonate should be immediately placed alive in a small glassine envelope. Odonata stored in jars can die with their wings tweaked in awkward angles. After the volunteer has finished their field work, they will want to properly preserve any

collected specimens with acetone. Acetone preserves specimen colors, prevents decom-position and is the preservative of choice. Specimens should be soaked in acetone for eight hours and then air dried before they are replaced in envelopes and sent to an expert for identification.

More detailed information on proper specimen preservation can be found by visiting the Wisconsin Odonata Survey Web site (see informational resources on the back page).

Identification

With a basic knowledge of species, volunteers should be able to identify

some adult Odonata observed in the field without capture, but most will be difficult to identify without closer examination. Even if you have an experienced Odonatist on hand they will likely only be able to identify about 50 percent of the species they see without capturing them. With capture, however, skilled volunteers may be able to identify 70 to 80 percent of the Odonata species encountered.

When a volunteer captures an odonate they are unable to identify, they can solicit the help of professionals through the Wisconsin Odonata Survey Web site. To solicit expert help, volunteers will either need a photograph or a specimen sample of the odonate in question. Photographs can be submitted through the online survey database. When taking photographs for identification purposes, the best angle from which to take a picture will depend on the species. When you submit a photo to Wisconsin Odonata Survey experts

for identification, they may reply back request-ing a photo from a different angle. To cover all of your bases, take clear shots from multiple angles including a photograph of the odonate’s face, a side view of its thorax, top and side of its tail and a general top view of its body.

In some cases volunteers may send experts a specimen rather than a picture. This practice

Wisconsin Odonata Survey Web sitehttp://wiatri.net/inventory/odonata

continued on page 6

Monitoring Your Wetland – Dragonflies & Damselflies

5

Data Collection and Recordkeeping

Whether they are keeping a captured odonate as a specimen sample, docu-

menting it with photographs or just taking down a written record of its presence, volunteers should always document the date and location where the specimen or photo was taken or obser-vation made. No specimen, photo or observation is worth anything to state Odonata experts without this basic infor-mation. If a volunteer would like to enhance collected data, they may want to include several other pieces of infor mation including air and water temperatures, weather conditions, what the odonate was doing or whether there were lots of them or just one.

To contribute to our greater understating of Wisconsin Odonata, volunteers can submit

collected data to the Wisconsin Odonata Survey database. Contributing data that can be used by the Wisconsin Odonata Survey is a gradual process. Generally, data base managers are

looking for data submitted by volunteer monitors who have demonstrated a high level of interest.

Although data submit-ted by beginners might not be included in the database, it can help the volunteers

establish a relationship with professional Odonatists who can help them cultivate their skills by providing volunteers with feedback on identifications. Once a monitoring volunteer has developed skills to identify common species in their area, they will begin to be able to contribute useful data that can be entered into the survey database.

is discouraged except among volunteers with relatively strong identification skills who know when they may have found something that merits sampling. Sending a specimen rather than a photograph is useful when capturing something that is unusual, since experts can

more easily identify species with a specimen than a photograph. When collecting specimens that cannot be identified in the field, a volunteer may want to try to collect two to three samples of the unidentified odonate.

Identification – continued from page 5

No specimen, photo or observation is worth anything to state Odonata experts without this basic information.”

“

Monitoring Your Wetland – Dragonflies & Damselflies

6

a primer to site-level monitoring activities for volunteer coordinatorsyourMonitoring

Wetland

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Dragonflies & Damselflies

INFORMATIONAL RESOURCE

Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources Odonata Survey This state Odonata survey Web site and database were developed to recruit volunteer support in helping DNR biologists learn more about Wisconsin’s Odonata species. The Web site provides many useful resources including tips on surveying Odonata, an online identification key and contact information for relevant DNR biologists. http://wiatri.net/inventory/odonata

(Odonata)

The Monitoring Your Wetland series includes 9 sections:

•IntroductiontoWetland Monitoring

•Birds

•SmallMammals

Dragonflies & Damselflies (Odonata)

•FrogsandToads(Anurans)

•Butterflies(Lepidoptera)

•InvasivePlants

•WaterQuality

•Macroinvertebrates

Available online in pdf format at:

wetlandmonitoring.uwex.edu

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .March 2011

Project coordination by the Rock River Coalition and Suzanne Wade, UW-Extension Basin Education Initiative.

Researched and written by Patrice Kohl

With editorial contributions from Bob DuBois, Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources biologist. Editorial assistance by Marie Martinelle and graphic design by Jeffrey J. Strobel, UW-Extension Environmental Resources Center. Photography by Jeffrey J. Strobel except where otherwise noted.

Project funded through a DNR Citizen-Based Monitoring Partnership Program Grant with support from University of Wisconsin-Extension.

University of Wisconsin, U.S. Department of Agriculture and Wisconsin counties cooperating. An EEO/AA employer, University of Wisconsin Extension provides equal opportunities in employment and programming, including Title IX and American with Disabilities (ADA) requirements.