Mongolia: Land of Nomads, Shamans and Buddhists for Magazine... · Mongolia: Land of Nomads,...

-

Upload

duonghuong -

Category

Documents

-

view

225 -

download

1

Transcript of Mongolia: Land of Nomads, Shamans and Buddhists for Magazine... · Mongolia: Land of Nomads,...

Mongolia: Land of Nomads, Shamans and Buddhists

Article: Christa Mackinnon Published in: Indie Shaman Magazine, Issue 18, 2013

Mongolia, in which 2.9 million people inhabit a space six times the size of the UK and where about 40% of people still live a nomadic, or semi-nomadic, way of life, is a country that touches the heart, provokes much thought and inspires in its uniqueness. I have been privileged to spend a few weeks there this summer and was enchanted by the land’s vast and wild beauty, the nomadic way of life, the connection between people, land and animals and the tangible spiritual/religious revival of Shamanism and Buddhism. Travelling in Mongolia touched something deep inside me. May be a long buried memory of how life was when we were all still ‘of the earth and of the sky’, when we encompassed the rhythms of nature within our own being, when we still lived simply. This expansive country certainly talks to us about that, which can only be experienced with wonder, with awe and with reverence: the magic of creation. Of course, Mongolia is, like so many other countries, not immune against the positives and negatives of modern development. Ulaan Bataar, the capital, inhabited by about 1.1million people, is one of the most polluted in the world. There is visible poverty and the current economic boom, mainly in form of mineral wealth, has led to economic inequality on a big scale. Nevertheless, 97% of Mongolians are literate, many speak more than one language, and the equality between women and men is striking. In fact, 80% of University students are girls and most of what is visible to the eye seems to be run by rather competent women. Whilst Ulaan Baatar is just another big capital city, the vast nomadic area is the place, where we can almost step back in time and experience a way of life that is fascinating in its simplicity and its inter-connection between humans, animals and the land in all its wild beauty. The Nomadic Way of Life One cannot understand Mongolia, nor its significant shamanic revival and what this might mean for the future, if one doesn’t comprehend the uniqueness of the Mongolian Nomads and their ancient connection to the land and the forces of nature.

The Nomads of Mongolia still live a traditional way of life with their herds. They usually move from summer pastures to winter pastures and some of them move from pasture to pasture a few times in between. Families inhabit transportable Gers, with extended families often living in small groups of 3-5 Gers, within a radius of a few hundred meters. The closest neighbours, depending on the area and the land, can be miles away, and the next village even further. Their herds, depending on grassland and wealth, are comprised of horses, cows, sheep and goats and, in the North of Reindeer and in the Gobi desert area also of Camels. The transportable Ger is a wonderful living space, similar to the one of a Yurd. It consists of a wooden structure, covered by layers of thick felt blankets. Inside, the Gers are decorated with colourful wall hangings and carpets. The beds, cupboards and the beams of the structure are usually beautifully pained in bright colours, with oranges, yellow, reds and greens dominating, and the Ger opening faces traditionally south. In the middle of the Ger is the hearth. It is used for cooking as well as for warmth and is mostly fired with dried dung. The hearth is light (no annoying health and safety regulations), with the chimney reaching out through the hole in the middle of the Ger. It can therefore be moved easily, just by removing the chimney, and families, including the men, often take it outside for cooking in summer. Most food is cooked in one big pot. The meat from the freshly slaughtered animal forms the first layer, then some potatoes, then leaves or some veggies on top. The Ger itself is divided along invisible lines, with the right side being the female side, home to workspaces, cupboards and the bed of the woman. The left side is the male space. It holds the hunting and herding gear and the bed for the man. The back of the Ger consists usually of a Buddhist altar, another bed or two, if the family is larger, and/or more storage spaces as well as the family photos next to the altar, showing the family members in ceremonial clothing. Nomadic families have strong ties. They depend on each other in their working, as well as their social lives. They sit inside or outside the Gers after lunch and in the evenings, chatting away, whilst the children run about, playing and having fun. Quite often neighbours come to visit on horseback, or more rarely on motorbikes, joining into the conversations. Striking is the equality between men and women. This is partly due to the fact that men were often away for days, tending the herds or, in earlier days, being warriors, and the women had to be able to do everything. It is also partly due to the policy of gender equality under the Sowjet influence, which was still seen as a ‘blessing’ by all the women I spoke to.

The nomadic people of Mongolia have a respectful relationship with the land and their animals. The animals are treated well. They are looked after, taken care of, cherished and left to lead relatively natural lives, but they are by no means seen in a sentimental light. They are, after all, the livelihood of the extended family. The animals graze in groups and are often

brought close to the Gers in the evening by the men of the family, with the cows and goats and sheep being herded into small, wooden enclosures by the riders for the daily milking, which is done by the women and children. The exceptional relationship between human and animal is especially tangible when it comes to horses. All Nomads are very skilled riders. If one watches them, the sentence ‘being at one with an animal’ takes on a new dimension. Horses, until they are sold in markets for meat or as racehorses, are used for herding, hunting, shopping, visiting neighbours, racing, games and to transport the Gers. Children, girls and boys alike, are often able to ride before they can walk and the relationship with the land and the herds develops naturally as they are included in all the daily chores as soon as they are old enough to participate. The Revival of Shamanism and Buddhism

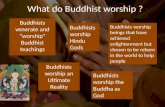

Wherever I went in Mongolia, I was confronted with a remarkable religious / spiritual tolerance. Mongolians look at the world from a Buddhist perspective, which most of them seem to combine easily with Shamanism. This became already obvious during the time of Genghis Khan, who himself was embedded in the shamanic tradition, but allowed the beginnings of Buddhist teachings. Buddhism entered Mongolia extensively during the 13th century and became the dominating religion of the entire country over the next few centuries, with the indigenous Shamanism increasingly incorporating Buddhist’ elements. A split begun to develop in the 18th century between the hunting tribes of the North, who rebelled against the power of the Buddhist rulers, and the infiltration of shamanism by Buddhism. This led to to the founding of ‘black shamanism’, a pure, traditional form, and ‘white and yellow shamanism’, forms more intermingled with Buddhism.

Shamanism and Buddhism were suppressed under the Sowjet regime. Since Mongolia’s democratic revolution and full independence, between 1989 and 1991, Buddhism has again become the main religion, but the revival of Shamanism can be felt everywhere and its popular attraction is, without doubt, increasing. Shamanism in Mongolia, embedded in the nomadic way of life since ancient times, has managed to survive against all odds, because the nomadic way of life hasn’t changed dramatically and also because shamans were individuals, rather than part of an organized spiritual/religious system, who could go underground and disappear during times of repression. The revival of Shamanism in Mongolia is also closely connected with the powerful revival of nationalistic pride, which centers around Genghis Khan, who united the Mongolian tribes and built an empire that stretched from the Caspian Sea to the Sea of Japan. The time of Genghis Kahn’s rule is associated with Mongolian statehood, political unity and power and, as Shamanism was the accepted and implemented spiritual way during Genghis Khan’s time, Mongolians often think of Shamanism as their primeval religion (yazguur šašin). It is seen as the essence of the Nomadic and Mongolian way of thinking, with father sky, mother earth and nature- and ancestor spirits at its core, and as it is more ancient then Buddhism, many people see it as being more indigenous to Mongolia

Traditionally, the Nomads of the vast steppes of Mongolia shared a nature-and spirit vision of the universe, and the world of human experience, and the shaman was the intermediary between the invisible forces of the spirit world and the seen universe. Shamanism was tied to all aspects of nomadic life and played a part on every level of society. The shaman and shamaness worked traditionally within trance states, embodying or utilized helping sprits, nature and ancestral spirits, ceremonial tools and ritualistic means. The shaman was protected against the ‘supernatural forces’ and aided by all the magical properties of his or her trade, starting with the headgear, often created from animals e.g. antlers from reindeers, wings for speed such as eagle feathers or owl feathers to help him see into the dark places, and the staffs, which were often crowned with a horses’ head. Drums made from hides were used for many reasons, from calling spirits to entering trance and one of the hallmarks of

Mongolian shamans in many areas is the metal mirror, originally coming from ancient China and used for divination, seeing, healing and more. Despite the shared nature- and spirit vision, as Mongolia is a vast country, the shamanic traditions were diverse. The recent revival also shows a range of practices, with some of them being still fairly pure, whilst others being re-invented, and many now represent a mixture of different ways and traditions and are also combined with Buddhist teachings, rituals and beliefs. Different forms exist mainly through the ethnic groups they were, and still are, embedded in. Darhads, which are closely related to the famous Tuvan shamans from the North West, are often regarded as the purest surviving form. Especially the shamans of the Tsaatans, one of the poorest ethnic groups, are referred to as the ‘pure Black’, without any Buddhist influence. Yellow and White Shamans are the ones which are influenced by Buddhist teachings and their work is seen often as more beneficial for people, albeit not pure. The well known Buryat shamans are in a territory heavily influenced through people descending from Russia. Again, distinctions seem to be made there between pure forms, such as black, and more mild forms, such as white. Opinions about ‘real shamanism’ seem to vary and, unfortunately, in Mongolia, just as in any other region of the world, one needs to practice discernment when it comes to neo-shamanism. The revival brought forth a number of people calling themselves ‘shamans’ who have little knowledge, experience and no traditional shamanic training or lineage. My stay in Mongolia was too brief to be able to gain full insight into the issue, but I have been told that most of the ‘real, traditional shamans’ can still be found in the North and West, mostly in areas difficult to access by modern transports, which kept the traditions fairly pure. Well known are the northern Mongolian groups, the already mentioned Darhad, Tsaatan, Hotgoit, the northeastern Mongols, the Buryat and Hamnigan and western Mongols, the Urianhai, all maintaining ancient shamanic traditions. Nevertheless, in Ulaan Baatar we can find hundreds, some say thousands, of shamans, and, even if they come from pure lines, the differences between them are getting slowly erased. The Mongolian Shamans’ Association, the Colomt Center for Shamanism, works towards preserving traditional shamanic ways and towards connecting Mongolease shamans with others around the world, but even there it is obvious that the modern world is infiltrating the teachings. When staying for a few days in Ulan Baatar right next to the urban shamanic center, called the ‘Center of Shaman and Eternal Heavenly Sophistication’, consisting of two big Gers, set between other, smaller Gers, at a busy intersection of main roads, surrounded by hotels and businesses, I watched the famous resident shaman practice his own brand of shamanism together with his wife. I wasn’t convinced that the channeling of Genghis Khan’s spirit healed the 20 or so Mongolian participants, but certainly felt something, and was quite taken in by the ritual, performed with high intensity.

Although my stay was too brief to figure out which of the shamans I met was real, traditional, fake, initiated and so on, I experienced first hand the extent to which Shamanism penetrates many aspects of normal Mongolian lives. So many customs are undoubtedly a mixture of the indigenous shamanic traditions and Buddhism, and everybody I spoke to, be it in Ulan Bataar or in nomadic areas knew a shaman, or of a shaman, or had been to see or consult a shaman and many people adhered to such traditional customs in a more or less intense way. Nomads and urban dwellers alike make offerings to the spirits of the lakes, grasslands, mountains and trees in form of milk, vodka, coins or food. Small offerings and rituals are performed often. Most of the nomadic women in the Gers, for instance, offered the traditional salted green milk tea to the spirit of the sky first, then to the Buddhist altar in the Ger and then to visitors. The moment we left a Ger, or a camp, we were blessed with milk, which was sprayed over us. Rituals and ceremonies to attract good weather, bless the arrival of animals or children are plentiful and so are the small, but important modes of behaviours that honour the spirits of elements and places: dumping waste into water offends the water spirits as does swimming when drunk; fire spirits also do not like to be fed with rubbish and they don’t like to look at exposed feet; the inners of a slaughtered animal have to be honoured and are offered to guests on arrivals (not very attractive to a vegetarian of 25 years standing, such as me). Wherever one travels in Mongolia, one is never far from an Ovoo. They are striking shamanic rock piles, sometimes surrounded by wooden slates, and always decorated with mainly blue khadags, silk prayer scarfs symbolizing the sky and the sky spirit, Tengri. They seem to be present everywhere: on mountain and hilltops, in open country and beside lakes and they are even dotted around Ulan Bataar and near Buddhist monasteries. Some of them, like the one near Karakorum, Genghis Khan’s former capital, reach lofty heights, whilst others are just a few feet tall. They are sacred shrines, nature-worshiping sites, asking us to honour the sky, the mountains, the spirits of the place and for a prayer. Animal skulls, mainly from horses, surround some of the Ovoos, intended to offer the spirits of the animals a ‘home’ should they wish for one. Mongolian people quite naturally honour the custom of circling an Ovoo three times in prayer when walking or riding, adding a stone to the pile to increase the power of the spirit of the place, whilst drivers of jeeps or motorbikes hoot three times when they pass one. I fell in love with those structures and the energies of the Ovoo places and must have circled at least 20 – 30 Ovoos during my relatively brief stay. Mongolia is an exciting place for everybody interested in Shamanism. It is a place where a nomadic way of life is supported by the population and the current government. It is a place where people, who are intimately connected to the land, remember and revive their indigenous traditions and where the nomadic population lives in a way that might be able to sustain them for generations to come. As long as these people, as well as the traditional shamans, who know about the forces behind the ‘seen world’, are not too tempted to turn everything, their land as well as their knowledge and wisdom, into saleable commodities, we might have a chance to witness a revival of shamanism like nowhere else, which will contribute to the much needed development of a nature-consciousness. I therefore want to close this brief article with the words of Byambadorj Zaarin, a shaman from the Mongolian Shamans Association:

“At this present time the human race is out of touch with Mother Earth, Father Heaven, and the natural world. By relating to them wrongly, by defacing and polluting nature, it is a great offense to Mother Earth, Father Heaven, and the nature spirits. There is great danger of fire, snowstorms, floods, and earthquakes. For this reason the shamans of

the earth need to work together to bring cleansing and healing to the earth, to do ritual together to restore balance. Because this cleansing and healing has not been done

the present state of the earth is the root cause of many problems and illnesses. This is the great work that shamans are now required to do.”

Copyright: Christa Mackinnon April 2013