MoF Issue 11

Transcript of MoF Issue 11

-

8/14/2019 MoF Issue 11

1/24

McKinsey onFinance

High techs coming consolidation 1

Economic pressures to restructure high tech will eventually become

irresistible. More acquisitions loom.

When efficient capital and operations go hand in hand 7

Olli-Pekka Kallasvuo, Nokias head of mobile phones and a formerCFO, discusses strategic organization, performance measurement, athe value of financial transparency.

All P/Es are not created equal 12

High price-to-earnings ratios are about more than just growth.Understanding the ingredients that go into a strong multiple can helexecutives make the most of this strategic tool.

Putting value back in value-based management 16

Value-based management programs focus too much on measuremenand too little on the management activities that create shareholder v

Perspectives on

Corporate Finance

and Strategy

Number 11, Spring

2004

-

8/14/2019 MoF Issue 11

2/24

McKinsey & Company is an international management-consulting firm serving corporate and government

institutions from 85 offices in 47 countries.

Editorial Board: Richard Dobbs, Marc Goedhart, Keiko Honda, Bill Javetski, Timothy Koller,

Robert McNish, Dennis Swinford

Editorial Contact: [email protected]

Editor: Dennis Swinford

External Relations Director: Joan Horrvich

Design and Layout: Kim Bartko

Circulation Manager: Kimberly Davenport

Copyright 2004 McKinsey & Company. All rights reserved.Cover images, left to right: Paul Schulenburg/Stock Illustration Source/Images.com, Corbis, Bonnie Rieser/

Photodisc Green/Getty Images, Timothy Cook/Stock Illustration Source/Images.com

This publication is not intended to be used as the basis for trading in the shares of any company or for undertaking

any other complex or significant financial transaction without consulting appropriate professional advisers.

No part of this publication may be copied or redistributed in any form without the prior written consent of

McKinsey & Company.

McKinsey on Finance is a quarterly publication written by experts and practitioners in McKinsey & Companys

Corporate Finance & Strategy Practice. It offers readers insights into value-creating strategies and the translation of

those strategies into stock market performance. This and archive issues of McKinsey on Finance are available online

at http://www.corporatefinance.mckinsey.com

-

8/14/2019 MoF Issue 11

3/24

For some time, the rules of economics

appeared not to apply to the high-

technology sector. Growth slowed, profits

shrank, and investors eagerly awaited the

billions of dollars in value likely to flow

from mergers, acquisitions, downsizings,

and liquidations. All signs pointed to an

imminent restructuring, yet until recently

little occurred.

Today consolidation pressures are mountingfast, and some segments have already

succumbed. Where operating systems for

PCs, midrange computers, and mainframes

were once numerous, now only a few

remain. Ditto for database software. Niche

players in segments such as vertical-specific

applications may remain fragmented, thanks

in part to the unique nature of the value

propositions they offer.

To develop a sense of how imminent

consolidation really is, and to pinpoint the

segments within and outside high tech that

might encounter challenges or opportunities

in the trend, we investigated the extent to

which the economic forces driving

consolidation were at play in 21 of the

sectors leading industries. The indicator

we looked at included each industrys

fragmentation levels, maturity (as measu

by growth rates), and profitability. We al

considered incentives for consolidation, s

as the need for scale to justify larger cap

expenditures and the importance of scop

to meet the customers changing needs.1

Where and how

We found strong signs of impending

restructuring in 11 of the industries we

analyzed (Exhibit 1). These hot spots

account for more than two-thirds of the

sectors revenuesa fact that speaks

volumes about its ripeness for consolidati

In IT services, for example, professional a

outsourcing services seem to be poised fo

an across-the-board restructuring. Softw

is vulnerable in particular areas, such as

enterprise applications, network and syst

management and security, middleware, an

software for application servers. In

hardware, the targets are PCs and notebo

computers, networking gear, and storage

systems; in semiconductors, they are logic

memory, and semiconductor equipment. research also found many small and mids

companies that are barely profitable, if at

all, with cost structures more appropriate

larger businesses (Exhibit 2).

As economic forces take effect, compani

will jockey for increased scale or scope o

for some combination of both (Exhibit 3

As in any sector, scale-driven mergers,

which aim to streamline fixed costs overgreater volumes and to satisfy the deman

for bigger and more stable suppliers, wil

mostly take place between companies

competing in the same industry. Custom

needs will also influence mergers that are

undertaken to achieve advantages of scop

Indeed, deals of this nature have already

High techs coming

consolidation

Economic pressures to restructure high tech

will eventually become irresistible. More

acquisitions loom.

High techs coming consolidation

Bertil E. Chappuis,

Kevin A. Frick, and

Paul J. Roche

-

8/14/2019 MoF Issue 11

4/24

taken place: in response to financialpressures and to the clamor of capital

markets, companies that manufacture

technology products have been acquiring

service firms. We expect such mergers to

proliferate as companies expand their

breadth of product or service offerings to

position themselves as preferred suppliers

for big customers, to chase new profit

streams, and to hunt for cross-selling and

multichannel synergies.

The semiconductor-equipment industry, for

one, is likely to see both scale and scope

come into play as companies prepare to

serve fewer and bigger semiconductor

manufacturers, only some of which will be

able to finance next-generation research and

fabrication plants. Consolidation hasalready taken place in certain pockets, such

as deposition, diffusion, and lithography,

but the industry as a whole remains

fragmented; only a handful of companies,

including Applied Materials and Tokyo

Electron, have significant positions in more

than one or two areas. The need to

consolidate will therefore inspire scale deal

in the few areas that are still fragmented

(automation, assembly, and packaging),while demand for complete process-module

solutions means that scope deals are likely

across industries. Vendors will thus capture

sales and marketing synergies by selling to

the same customer base. Moreover, an

integrated solution across related areas

(such as deposition and etching) can shorte

2 | McKinsey on Finance | Spring 2004

1Metrics examined include market growth rate, 200207 (industry maturity); HerfindahlHirschman Index (fragmentation levels); number of top 10companies with negative earnings before interest and taxes in 2002 (industry profitability); qualitative assessment of scale, scope, changes in customerbuying behavior (incentives for consolidation).

Source: McKinsey analysis

e x h i b i t 1

Ripe for restructuring

Key IT industries and segments,1 2002, % of revenues

Ripe for restructuring

Network/systemsmanagement, security

Middleware,application server

Enterprise applications

Operating systems

Vertical applications

Database

Desktop applications

Storage

Software ($146 billion)

PCs/notebooks

Networking

Servers

Smart handhelds

Printers

Storage

Hardware ($299 billion)

IT services ($243 billion)

Professional andoutsourcing services

17

35

28

20

Semiconductor equipment

Logic

Microcomponents

Memory

Analog

Discrete

Semiconductors ($174 billion)

-

8/14/2019 MoF Issue 11

5/24

development cycles and ramp-up times. The

enterprise software market will restructure

along similar lines.

Restructuring could also be triggered by

companies that exit an industry altogether.

This is likely to happen in the PC business if

some incumbents decide that the benefits of

merging are questionable in light of theindustrys deteriorating economics. Finally,

where mergers and acquisitions dont make

sense, companies might forge alliances or

transform themselves without resorting to

alliances or M&A.

Shape IT or leave IT

The economic rationale for consolidation

might be similar in all sectors of the

economy, but restructuring unfolds in waysspecific to each of them. In the same vein,

our perspective on how to respond to

high-tech consolidation begins at a general

level (Exhibit 4), then tackles specifics.

Well examine the two classic roles

market leader and challengerbefore

discussing the advantages for M&A of

the long view and the need to prepare fo

more hostile deals.

Leaders and challengers

When industries consolidate, market lead

and challengers can make acquisitions

within their industries to create economi

of scale or across industries to gain

economies of scope. To know what to doand when, companies need to develop a

perspective on restructuring trends and t

way these affect their particular industry

envision the likely endgame, they should

consider shifts in customer behavior and

factors required for success. And as they

make their moves, they must evaluate ho

competitors will probably respond.

Market leaders. In restructuring sectors,market leaders aim to protect their posit

from challengers while seizing opportuni

to extend their dominance; they therefor

make acquisitions to head off those

challengers and to increase their scale. In

the high-tech sector as a whole, market

leaders should defend the customer base

High techs coming consolidation

e x h i b i t 2

Unsustainable

Average EBIT1 margin of public IT companies by revenues,2 2002, %

1Earnings before interest and taxes.2Includes 2,121 companies worldwide in software (913), hardware (562), IT services (266), semiconductors (380).

Source: Bloomberg; Thomson Financial; McKinsey analysis

$5 billion

320

1

2

2

12

11

29

SoftwareRevenues

167

1

1

2

4

3

5

Hardware

29

3

4

5

6

6

6

IT Services

59

Semiconductors

1

9

1

2

4

-

8/14/2019 MoF Issue 11

6/24

4 | McKinsey on Finance | Spring 2004

e x h i b i t 3

Scale, scope, or skedaddle

1 Selling, general, and administrative.

Source: McKinsey analysis

Restructuring activity Drivers Examples

Scale: peer consolidation Improved fixed-cost structures (SG&A,1 R&D,depreciation)

Customer preference for bigger suppliers

Network, platform effects

Logic

Memory

Network/systems management, security Storage hardware

Scope: strategic cross-segment moves

Customer preference for broader-reaching suppliers

Channel, cross-selling synergies

Technological synergies (such as those betweennetworking and storage)

Value migration from hardware to software, services

Maturing core businesses; capital market pressuresfor growth

Database: middleware, application server

Hardware: IT services

Exit Desire to limit losses, free up capital

Refocusing resources on other businesses

Logic

PCs/notebooks

Networking hardware: storagehardware, software

Semiconductor equipment

tightening their control of the value chain

and customer relationships or by creating

scale advantages in R&D and sales. Oracle,

for instance, is pursuing a broader footprint

and new growth in its play for PeopleSoft.

Scale offers efficiencies in large fixed costs

essential in industries requiring massive

up-front capital investment (like memorychips) or expensive R&D (like software). It

also extends control over the value chain.

Customers gain confidence in the vendors

ability to provide long-term support services

and are more likely to choose it as a

preferred supplier. HPs merger with

Compaq, for example, gave HP enhanced

control over its value chain, cost synergies,

and access to additional customers, to which

it could now sell more comprehensivesolutions. These factors should help HP

compete with IBM and Dell.

Scope acquisitions can broaden the

footprint of a leader and increase the

dependence of its customers. Cisco Systems

growth strategy in the 1990s was based on

scope acquisitions, and the company swiftly

used its distribution capabilities to stake ou

strong positions in access solutions and

security. Microsofts purchase of Great

Plains Software and Navision extended its

reach into enterprise applications. EMCs

acquisition of Legato Systems presaged a

move away from the slower-growth and

rapidly commoditizing storage-disk-subsystem market and into the system-

management-software marketa core

control point of an enterprise IT

infrastructure. The companys decision to

buy Documentum shows a similar move

into content management.

For companies in some segments,

such as IT services, scope deals offer

an opportunity to become the primeintegrator for customers needs; IBMs

acquisition of the consulting arm of

PricewaterhouseCoopers is a recent

example. A few words of warning should

be sounded, however: if the acquisition has

a different revenue model (as in the case of

a hardware company acquiring a software

-

8/14/2019 MoF Issue 11

7/24

e x h i b i t 4

The big picture

Type of company Scale

Market leaders Grow bigger;buy or blockchallengers

Exit

Challengers Merge withpeers

Scope

Cross-sell toboost customerdependence

Buy adjacentbusinesses

Small companies Carve out

sustainable niche

Maximize

sale value

Strategy

Source: McKinsey analysis

one), the buyer must avoid compromising

the targets underlying business model.

Challengers. Typically, a challenger in a

restructuring industry confronts industry

leaders by rolling up smaller companies

to achieve scale or by merging with another

challenger, thereby driving radical cost-

structure changes through operational

integration and redesigned business

processes. PeopleSofts acquisition of

J. D. Edwards in enterprise applications

provides a good example of a challenger

buying a peer to reduce operating costs.

The combined company can use its largerscale to become a preferred supplier to

key customers.

Alternatively, a challenger can attempt to

extend its scope by acquiring players in

adjacent industries and combining the

offerings into solutions, with the eventual

aim of changing the basis of competition.

BEA Systems, for example, started with a

transaction-processing product and then, byacquiring companies such as WebLogic,

gained leadership in the application server

and middleware market, where we expect

further consolidation. Second-tier storage

and networking vendors could also benefit

from teaming up in this way, as might

companies in middleware and network

management. In semiconductors, several

companies could combine to form a larg

chip maker focused on consumer

electronics. (Beyond high tech, banks suc

as Morgan Stanley and UBS Warburg hav

used scope combinations to reposition

themselves as financial-services providers

Such deals challenge the acquirer to crea

compelling value proposition and to buil

sales force that can communicate it

forcefully enough to displace incumbents

If confronting the market leader directly

too risky, companies can pair up to carv

out a defendable niche. IT service provid

could take this approach in health care, s

if they found themselves unable to comp

more broadly. Aspiring niche players mu

assess whether they can create sustainabl

entry barriers based on proprietary

technology, innovation, industry knowled

or locked-up customer ties.

Selling out. Finally, the best way to recou

value is sometimes to sell part or all of a

company. In this case, it is often wise to

move sooner rather than later to get thehighest value for shares and to position t

company in the most attractive light, wh

may mean shedding noncore assets. Such

moves sometimes unlock resources that c

be reinvested to make a company stronge

in more strategic segments.

The long view

Market reactions to merger announceme

tend to favor the target; fewer than halfhigh-tech acquirers see their shares rise a

disclosing their plans. No wonder boards

and executives are wary of acquisitions.

the most successful high-tech companies

those averaging more than 39 percent

annual growth in returns to shareholders

from 1989 to 2001were serious deal

High techs coming consolidation

-

8/14/2019 MoF Issue 11

8/24

makers, undertaking almost twice as many

acquisitions as their competitors.2 History

also shows that companies with active

M&A agendas tend to outperform their

peers during and after industry downturns.3

Companies that avoid acquisitions often run

out of steam, whereas enterprising acquirers

renew and refocus themselves.

Companies should be cognizant of, but not

overly concerned with, investors short-term

reactions. Instead, they need to ensure that

the long-term returns from their acquisition

plans maximize shareholder value. Take

Intel, which in recent years has acquired

several suppliers of communications chips.

Not all of the deals have been applauded as

successful by observers (for example, the

acquisition of Level One Communications),

but together they helped Intel establish a

new communications growth platform on

which the company has built a multibillion-

dollar business.

High valuations can sometimes make

alliances more enticing than M&A,

especially if synergies wouldnt justify a fullacquisition. Dells recent alliances with

EMC and Lexmark are examples of how

these arrangements can be used as a low-

risk step to broaden a companys scope into

new segments.

More hostile deals

Most technology mergers have been small,

friendly affairs financed by the acquirers

stock, but we expect that picture to change.Oracles attempt to acquire PeopleSoft is an

early example of what could become the

new reality in high-tech restructuring.

Executives and boards should thus prepare

for hostile takeovers, cash deals, and the

greater involvement of private equity

firmsall common in other sectors.

Furthermore, as companies reach for scale

and scope, they will attempt larger deals.

While a hostile takeover is rarely the

preferred approach, these deals are likely to

become more common, especially when the

targets management has strong incentives

to resist an acquisition that has real

economic logic. For acquirers with deep

pockets, cash offers may be more attractive

in hostile situations, when cash can give

shareholders a low-risk way to take money

out of their investments.

The scale and extent of the coming shifts in

the high-tech sector promise to unlock

tremendous value for companies that

survive the consolidation. However quickly

change comes, those that act wisely can

position themselves as the shapers of high

techs next era.

The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of

Jukka Alanen and Jean-Francois Van Kerckhove,

consultants in McKinseys Silicon Valley office.

Bertil Chappuis ([email protected])

andPaul Roche ([email protected])are

principals in McKinseys Silicon Valley office, where

Kevin Frick([email protected])is an

associate principal. Copyright 2004 McKinsey &

Company. All rights reserved.

1 To measure the strength of each driver, we used qualitativ

and quantitative metrics such as the Herfindahl-Hirschma

Index (a common metric established by the US

Department of Justice and the US Federal Trade

Commission) to assess the current degree of

fragmentation.

2 Kevin A. Frick and Alberto Torres, Learning from high-tec

deals, The McKinsey Quarterly, 2002 Number 1,

pp. 11223.

3 Richard F. Dobbs, Tomas Karakolev, and Francis Malige,

Learning to love recessions, The McKinsey Quarterly,

2002 special edition: Risk and resilience, pp. 69.

MoF

6 | McKinsey on Finance | Spring 2004

-

8/14/2019 MoF Issue 11

9/24

When efficient capital

and operations go hand

in hand

Olli-Pekka Kallasvuo, Nokias head of mobile

phones and a former CFO, discusses strategic

organization, performance measurement, and

the value of financial transparency.

When efficient capital and operations go hand in hand

Nokias transformation from a Finnish

conglomerate with its roots in pulp and

paper to the worlds leading mobile-phone

supplier has earned it a reputation as a

model of innovation, brand building, and

operational efficiency. Even during the

severe downturn in the telecommunications

industry the company maintained strong

margins on its sales of mobile phones.

Today Nokia runs 16 manufacturing

facilities in 9 countries, conducts R&D in11 countries, and has more than 51,000

employees around the world

Nokia is reorganizing itself yet again as it

anticipates increased demand for high-tech

phones and other mobility products.

A base of four business groupsmobile

phones, networks, multimedia, and

enterprise solutionswill exploit scale

advantages across common functions suchas finance, marketing, and operations to

provide maximum flexibility for business

units. The goal: to go after every market

in this industry and take share.

So says Olli-Pekka Kallasvuo, who in

January of this year was named head of the

mobile-phones group after serving as ch

financial officer from 1992 to 1996 and

1999 to 2003. A lawyer by training,

Kallasvuo, 50, sees his move from finan

to the leadership of the business group

responsible for most of Nokias profits a

perfectly natural. In an interview condu

at Nokia headquarters outside Helsinki,

Kallasvuo spoke to Fredrik Lind and

Risto Perttunen of McKinsey about Nok

strategy, communicating with markets, a

the CFOs mind-set when operational an

capital efficiencies go hand in hand.

McKinsey on Finance: What long-term

trends in the handset business do you see,

and how are they affecting Nokias strate

Kallasvuo: The biggest long-term trend i

our customers increasing mobility and, a

result, their demands for ever more

sophisticated handsets. In one sense, its

kind of convergence of businesses into a

new business domain defined by mobility

The result is that well continue to see a

very simplistic entry-level phone, with no

bells and whistles, on one hand, and on other hand well see a multipurpose devi

that has all sorts of capabilities, like mob

gaming or mobile imaging. This is what

need to tackle at Nokia, and hence the

reorganization to align our structure to

different segments of this market.

MoF: How do you think about measurin

performance?

Kallasvuo: The thinking over the years

has definitely changed. Weve learned to

understand that for us, traditional measu

of performance like working capital, for

example, are financial matters, yes, but

more important theyre indicators of how

a company is performing operationally.

Fredrik Lind and

Risto Perttunen

-

8/14/2019 MoF Issue 11

10/24

8 | McKinsey on Finance | Spring 2004

When I look at working capital, I really

see it first as a reflection of efficiency and

then as a reflection of where our capital is

invested, which is the reverse of the usual

way of thinking.

MoF: So how do you track the companys

performance over time?

Kallasvuo: A more capital-intensive

business would probably look much more

closely at its returns on investment, but

ROI just is not as useful a measure for a

company that makes its money by investing

in people, in research and development, andin brand marketing. Measures of efficiency

are much more helpfuloperational

efficiencies, production efficiencies, and yes,

financial efficienciesand they really all go

hand in hand. Production efficiencies and

capital efficiencies are very relevant for

every finance person at Nokia.

And if there were just one single thing to

do to improve performance, it would have

been done already. Improvement is usually

not about making a quantum leap; its

about taking small steps, improving a little

bit every day. Nor is this about pushing

responsibility off to individual departments

and saying, You look at working capital,

or, You look at inventory. These are the

responsibility of everyone at Nokia becaus

efficiency is the core of the business

and then working capital becomes a

reflection of how efficient we are, and

thats why its such an important indicator

that remains very high on our agenda even

if financially its not critically relevant at

the moment.

MoF: Can the corporate team and the CFO

team contribute to and lead the different

divisions and businesses on the working

capital dimension?

Kallasvuo: No; this is exactly the point.

Efficiency is so intricately entwined in the

system that everyone has a stake in it,

everyone is helping out. So if you were tostart some big push for working capital at

Nokia, with a big headline saying, Now w

are going to emphasize working capital, or

announce that suddenly financial concerns

will drive everything, no one would

understand what youre talking about.

Everyone understands that working capital i

everyones jobby taking those little steps

to get logistics working even better. This is

one of our key competitive areas.

MoF: Are there any particular structures

or processes at Nokia to make this

cooperation work?

Kallasvuo: In the end, it really comes down

to a companys business infrastructure and

Olli-Pekka Kallasvuo

Vital statistics Born July 13, 1953, in Lavia, in western Finland

Education Holds a Master of Laws degree from the University of Helsinki

Career highlights Nokia, Inc. (1980 to present)

Assistant vice president of the legal department (1987) Assistant vice president of finance (1988) Senior vice president of finance (1990) Executive vice president and chief financial officer (1992 to 1996) Corporate executive vice president, Nokia Americas (1997 to1998) Chief financial officer (1999 to 2003) Executive vice president and general manager of mobile phones at

Nokia (2004present)

Fast facts Served as chair and board member of Helsinki Stock Exchange from

1991 to 1996 Serves on the boards of:

Sampo, a Finnish full-service financial group Nextrom Holding, a Swiss machine manufacturer F-Secure, a Finnish company specializing in data security solutions

In spare time, enjoys golf, tennis, and reading about political history

-

8/14/2019 MoF Issue 11

11/24

how it operates in general. As we have

grown from a small, flexible player to such

a large company, weve put considerable

effort into combining flexibility and

economies of scale, which has an impact on

how we operate. The emphasis has been on

doing everything we can to take advantage

of economies of scale where we can and

where it makes sense, but not to centralize

anything that is business specific. Weve

drawn that line very carefully. If something

is business specific, it gets maximum

flexibility, empowerment, decentralization.

If its not business specific, then lets take

the economies of scale. The result has been

an increasing platformization, if you will, of

the business infrastructure. And here the

business infrastructure means other than IT,

so its a wider concept.

MoF: What have been the special challenges

of communicating the results of a very fast-

growing company to financial markets?

Kallasvuo: Communicating results is easy.

Giving estimates is more of a challenge,

because in this type of fast-moving businessno one can really know what will happen

over three monthsno one. No system in

this world can make that prediction in a

way that is certain. The best you can do is

communicate your best understanding to

the market at the time, which is actually

pretty simple.

At Nokia, we have been simply communi-

cating our best possible understanding tothe market. We have not been playing

games. I was personally criticized by some

investors for not playing gamesfor not

giving an estimate and then exceeding it by

one penny, which so many companies were

doing. Now, of course, everyone feels this

way. Whatever numbers come out of the

system, in accordance with your account

principles, those are your results.

MoF: What is your view of the emergen

of companies over the past year or so th

are minimizing their financial transparen

to the markets?

Kallasvuo: Of course, I cant speak on

behalf of other companies, but I feel tha

our investor base wants quarterly guidan

Its very much a matter of providing the

markets with the information they want,

rather than telling them what we think t

should want. This isnt brain surgery. If t

markets want information, you give them

information.

The question has to be, how can we bett

understand what our investors want? Th

mind-set really needs to be that we must

listen and communicate in terms of what

expected. This is very relevant coming fr

a small market and growing into one of

most traded shares in the world. We com

from a context where we really didnt ha

the benefit of the doubt when it came toour existence and our ability to deliver o

the long-term. It really was an imperativ

listen to what investors expectedif we

not have that mind-set, we never would

have become one of the most widely held

shares in the United States.

MoF: What is the optimal way to distribu

value back to the shareholdersfor exam

through share buybacks or dividends?

Kallasvuo: I dont think there is a big

difference between dividends and buybac

In the end its a pragmatic choice, very

much driven by tax questions and the

shareholder base. Otherwise theyre both

pretty equal from the financial perspecti

When efficient capital and operations go hand in hand

-

8/14/2019 MoF Issue 11

12/24

10 | McKinsey on Finance | Spring 2004

MoF: How important is it for a company to

be listed in the United States?

Kallasvuo: Its really not possible to

become a major name among US investors

if youre not represented in the US market

in a major way. Being listed supports the

business, and the business supports the

listingwhich Nokias experience in the

1990s illustrates very well. Indeed, I

would claim that without its listing in

New York, Nokia would not have become

the market leader in the United States.

Furthermore, if it had not become a

market leader in the United States, the

share story would have been a lot less well-

known. When we first issued our IPO in

the United States, it wasnt really that we

needed US capital but rather that the listing

would support the business, which is how

it worked out. The result was a positive

spiral, if there is such a thing, each one

supporting the other.

MoF: And how has that transformation

changed your relationship with shareholders

on both sides of the Atlantic?

Kallasvuo: Sometime in 1995 or 1996,

we became the first company in the world

with a major market cap that had the

majority of its market capitalization coming

from outside its home country, as domestic

Finnish share dipped below 50 percent.

That happened very suddenly and

continued at a rapid pace. Other

companies have since found themselves insimilar positions, but not to the same

extent. So we basically said to ourselves,

Now we have to see ourselves as a

US company and we have to do things in

the same way a US company would,

because thats what a majority of our

investors will expect.

That became a real priority. For example,

instead of having our US investor relations

(IR) staff report to an IR executive in

Helsinki, we located the IR head office for

the entire company in the United Statesan

then of course allocated a lot of resources

and everything to make it work. Even the

Helsinki-based IR office reported for many

years to the US office. When it came to

communications, we said to ourselves, we

need to communicate like a US company.

Even today, if some capital-markets-related

legislation or other comes out of the United

States that isnt necessarily applicable to

non-US companies, we comply anyway, eve

if the legislation does not, strictly speaking

apply. There is no other way for us.

Other companies have chosen exactly the

other way: to be domestic first and

foremost, abiding primarily by their own

governments practices and legislation and

domestic shareholders. Which one is wrong

or right I cant say.

MoF: And how comfortable are you with

Nokias current level of transparency?

Kallasvuo: I can say that every time we hav

had a discussion internally about whether

we should go into this more transparent

reporting, and every time we have made a

decision to report instead of holding back,

the decision to report has been the right

decision, eventually. Its what I feel. Not

once have I looked back and thought, Why

did we have to tell this? But here again,I would suggest that theories aside, in our

case its been a necessity. You are foreign.

You are an ADR.1 You dont have the optio

of not listening to what the market wants.

MoF: Is there any risk, as Nokia begins

reporting separately for multimedia

-

8/14/2019 MoF Issue 11

13/24

handsets and enterprise solutions? What if

one unit doesnt achieve very good results?

Kallasvuo: No, definitely not. As I said,

every time weve increased our transparency

it was the right decision, so it must be the

right decision here too. And you have to also

remember that external pressure is good for

you. It makes you run even harder. The

people running those operations have even

more reason to perform if external pressure

is there also. Thats been our experience.

MoF: Has the CFO been a part of the

strategic decision-making process in Nokia,

and do you see that role being strengthened

in the future?

Kallasvuo: I dont really think there is one

and only one role for a CFO. Of course, the

role of a CFO has to be aligned with the way

the company operates, and it also depends

very much on the size of the company. But it

really cant be the same in every company, in

every business situation, and in every type of

business a company is in.

At Nokia, being CFO has meant being

very much a part of the management

team, looking at matters from a financial

perspective but really not taking the role

of a finance guy who primarily becomes

the voice of that department. Instead of

defining the role in one way and taking

that into the management team, the CFO

at Nokia has a responsibility for the same

decisions as everyone else on themanagement team. Yes, of course, you

might look at those decisions from a

certain perspective, but that doesnt have

to mean that you always take the same

sort of role. You have to be more versatile

than that, which makes the role a very

strategic one.

MoF: In many companies, the role of th

CFO has been expanding on the traditio

role in two directions: the first is a more

strategic-architect or strategic-planning t

of role, even to the point of having M&

or strategy divisions; the second is movin

toward a more involved operations role,

enhancing some business-controlling

activities or leading corporate-pricing or

working-capital programs. What are you

thoughts on the evolution of the CFO ro

in general?

Kallasvuo: If you assume a traditional so

of controller role as the starting point, th

yes, those are the two natural directions

the role to evolve. But because it varies

depending on how the company operates

its also possible that both of those roles

might even be combined. The latter role

the more involved operations roleis

particularly apt for the CFO of a major

business unit, which is very much an

operational role in an operational unit.

The former, more strategic role is more a

for a corporate, head-office CFO who

operates, supervises, and oversees severabusiness units. And both are quite releva

at Nokia, too, because of how we opera

and how the roles of the business units o

even business groups have been defined.

And I would also claim that the role of t

CFO must be aligned to the approach of

the CEO. Without alignment, success is

difficult.

Fredrik Lind([email protected])is a

principal in McKinseys Stockholm office, and

Risto Perttunen ([email protected]

is a director in the Helsinki office. Copyright 200

McKinsey & Company. All rights reserved.

1American depository receipt

MoF

When efficient capital and operations go hand in hand

-

8/14/2019 MoF Issue 11

14/24

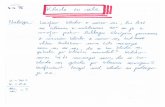

e x h i b i t 1

Companies can have identical P/E multiplesfor dramatically different reasons

1Assuming 10% cost of equity, no debt, and 10 years excessive growthfollowed by 5% growth at historic levels of returns on invested capital.

Source: McKinsey analysis

ExpectedROIC

Expectedgrowth

Implied P/Emultiple1

Growth, Inc 14% 13% 17

Returns, Inc 35% 5% 17

All P/Es are not

created equal

High price-to-earnings ratios are about more

than growth. Understanding the ingredients that

go into a strong multiple can help executives

make the most of this strategic tool.

When it comes to price-to-earnings ratios,

most executives understand that a high

multiple enhances a companys strategic

freedom. Among other benefits, strong

multiples can provide more muscle to

pursue acquisitions or cut the cost of

raising equity capital. Unfortunately, in

their efforts to increase their P/E, many

executives reflexively try to crank up

growth. Too many fail to appreciate the

important role that returns on capitalplay in channeling growth into a high or

low multiple.

Simply put, growth rates and multiples dont

move in lockstep. For instance, the retailer

Williams-Sonoma has a P/E multiple of

about 21, based on earnings growth over

15 percent in the past three to five years

and low returns on capital.1 By contrast,

Coca-Cola has a slightly stronger P/E at 24,despite its lower growth rate.2 Cokes

secret? Returns on capital over 45 percent

relative to a 9 percent weighted average cost

of capital.

Its common sense: growth requires

investment, and if the investment doesnt

yield an adequate return over the cost of

capital, it wont create shareholder value.

That means no boost to share price and no

increase in the P/E multiple. Executives wh

do not pay attention to both growth and

returns on capital run the risk of achieving

their growth objectives but leaving behind

the benefits of a higher P/E and, more

important, not creating value for

shareholders. They may also discover that

they have confused their portfolio and

investment strategies by treating some high

P/E businesses as attractive growth

platforms when they are actually high-

returning mature businesses with few

growth prospects.3 Better understanding of

the way growth and returns on capital

combine to shape each businesss multiple

can produce both better growth and better

investment decisions.

Doing the math on multiples

The relationship between P/E multiples and

growth is basic arithmetic:4 high multiples

can result from high returns on capital in

average or low-growth businesses just as

easily as they can result from high growth.But beware: any amount of growth at low

returns on capital will not lead to a high

P/E, because such growth does not create

shareholder value.

12 | McKinsey on Finance | Spring 2004

Nidhi Chadda,

Robert S. McNish,

and Werner Rehm

-

8/14/2019 MoF Issue 11

15/24

To illustrate, consider two companies with

identical P/E multiples of 17 but with

different mechanisms for creating value.

(Exhibit 1). Growth, Inc., is expected to

grow at an average annual rate of

13 percent over the next ten years, while

generating a 14 percent return on invested

capital (ROIC) which is modestly higher

than its 10 percent cost of capital. To

sustain that level of growth, it must

reinvest 93 cents from each dollar of

income (Exhibit 2). The relatively highreinvestment rate means that Growth, Inc.,

turns only a small amount of earnings

growth into free cash flow growth. Many

companies fit this growth profile, including

some that need to reinvest more than

100 percent of their earnings to support

their growth rate. In contrast,

Returns, Inc., is expected to grow at only

5 percent per year, a rate similar to long-

term nominal GDP growth in the UnitedStates.5 Unlike Growth, Inc., however,

Returns, Inc., invests its capital extremely

efficiently. With a return on capital of 35

percent, it needs to reinvest only 14 cents

of each dollar to sustain its growth. As its

earnings grow, Returns, Inc., methodically

turns them into free cash flow.

Because Growth, Inc., and Returns, Inc.,

take very different routes to the same

P/E multiple, it would make sense for a

savvy executive to pursue different grow

and investment strategies to increase eac

businesss P/E. Obviously, the rare compa

that can combine high growth with high

returns on capital should enjoy extremely

high multiples.

The hard part: Disaggregating

multiples

Not many executives and analysts work

discern how much of a companys curren

value can be attributed to expected grow

or to returns on capital. Those who try

often fail. To see why, consider one wide

used model to break down multiples as i

might be applied to a large consumer go

manufacturer and a fast-growing retailer

with similar P/E ratios (Exhibit 3).

The first step is to estimate the value of

current earnings in perpetuity, assuming

growth.6 The model then attributes the

remaining value to growth. The

interpretation from this simple two-partapproach would be that the market assum

that the consumer goods manufacturer

would have better growth prospects than

the retailer.

But this reading misleads because it doesn

take into account returns on capital.

Discount retailers fight it out primarily on

price, which translates into lower margin

and relatively low returns on capitalsimto Growth, Inc. In contrast, consumer go

companies compete in an environment wh

brand equity can generate higher margins

and returns on capital, making them mor

like Returns, Inc. In fact, the simple two-

model is wrong. The discount retailer is

actually expected to grow faster and to

All P/Es are not created equal

e x h i b i t 2

Sustaining high growth requires considerablymore reinvestment than sustaining high returns

1Assuming 10% cost of equity, no debt, and 10 years excessive growthfollowed by 5% growth at historic levels of return on invested capital.

Source: McKinsey analysis

Growth, Inc1 Returns, Inc1

Operating profit less taxes

Year 1 Year 2 Year 1

Reinvestment rate93%

Reinvestment rate14%

Year 2

100 113 100 105

93 105 14 15

7 8 86 90

Reinvestment

Free cash flow

-

8/14/2019 MoF Issue 11

16/24

e x h i b i t 3

Traditional assessments of enterprise value can lead to a misinterpretation of where valuecomes from

1Return on invested capital.2From 2004 to 2018.

Source: Compustat; Zacks; McKinsey analysis

100% = operating enterprise value

Traditional decomposition

Consumer goods manufacturer, P/E: 20

Fast-growing retailer, P/E: 20

52%48%

50%50%

ROIC1-growth decompositionROIC: 38%Implied growth: 5.1%

ROIC: 12%Implied growth: 9.5%2

21%

2%

29%

50%

50%

48%

Value from currentperformancewith no growth

ROIC premiumValue from currentearnings in perpetuity

Value from futureearnings

Value ofexpected growth

14 | McKinsey on Finance | Spring 2004

create more value from growth than the

consumer goods company, whose high

valuation would be primarily based on high

returns on capital.

An executive relying on the faulty analysis

produced by such a simple model might flirt

with trouble. The CEO of the consumer-

goods company

might increase

investment or

discount prices todrive growth,

potentially

destroying

shareholder value

in the long run. By

digging a little

deeper and

appreciating the

role of returns on

capital, the CEO would more likely focus onprotecting high returns and market share.

Accounting for the ROIC premium

How can we avoid these misinterpretations

and still keep the analysis relatively simple?

In our experience, the best way to

understand the respective roles of returns

on capital and growth in shaping a

companys P/E is to expand the simple

two-part model and draw out a P/E

premium for high returns on invested

capital. This approach effectively

disaggregates value into three easily

understood parts:

Current performance. Current performance

is still estimated in the usual manner, as the

value of current after-tax operating earning

in perpetuity, assuming no growth.Intuitively, this is the value of simply

maintaining the investments the company

has already made.

Return premium. This is the value a

company delivers by earning superior

returns on its growth capital. In order to

assess how a companys return on

growth capital influences its P/E multiple,

we recommend discounting a companyscash flows as if they grew in perpetuity at

some normalized rate, such as nominal

GDP growth.7 Through repeated analyses,

we have found that the result is a good

proxy for the premium a company enjoys

in the capital markets because of its high

returns on future growth capital. In our

The best way to understand

the respective roles of returns

on capital and growth in

shaping a companys P/E is

to expand the simple two-

part model to draw out a

premium for high returns

on invested capital.

-

8/14/2019 MoF Issue 11

17/24

example, the consumer goods manufacturer

would enjoy a large return premium,

consistent with its high historical returns

on capital.

Value from growth. This value represents

how much a company delivers by growing

over and above nominal GDP growth. It can

be calculated as that portion of the

companys current market value that is not

captured in current performance or the

return premium.8 While more sophisticated

and time-consuming analyses are sometimes

appropriate, in our experience executives

can learn a lot about their P/E multiple with

this simple three-

part model.

How might an

executive change

his or her insights

about the consumer

goods company and

the discount retailer

using this three-part

model? The consumer goods company

would be seen to enjoy a large premium forits return on capital. In the consumer goods

sector, preserving that return premium must

be paramount, but anything the company

can do to increase its organic growth rate

while preserving its return premium would

translate directly into shareholder value and

the possibility of a very high multiple.

In contrast, the CEO of the discount retailer

would face a tiny premium for return oncapital, since his or her company derives

most of its value from the rapid growth

prospects. Anything this company could do

to increase its ROIC, possibly even reining

in its growth rate, would add value. By

applying the model to calibrate the trade-off

between growth and return, the CEO could

even determine that a top management

priority is to redirect some attention from

growth to operations improvement.

High P/E multiples can serve as a powerfstrategic tool. Executives who understan

the complex chemistry of growth, return

and P/E multiples will be better position

to make strategic and operating decision

that increase shareholder value.

Nidhi Chadda ([email protected])

and Werner Rehm ([email protected]

are consultants in McKinseys New York office.

Rob McNish ([email protected])is aprincipal in the Washington, DC, office.

Copyright 2004, McKinsey & Company.

All rights reserved.

1Adjusted for operating leases, Williams-Sonomas ROI

has historically averaged about 10 percent, the same

cost of capital.

2 Coke reports earnings around 3 percent over the past

seven years.

3 Likewise, stock market investors can make the same

mistake by thinking they are investing in high P/E grostocks when in fact some of these stocks are high-

returning value investments.

4 For instance, assuming perpetuity growth for a compa

without any financial leverage, P/E = (1 growth/retur

capital)/(cost of capital growth).

5 Real GDP growth over the past 40 years in the United

States was 3.5 percent.

6At no growth, we assume that depreciation is equal to

capital expenditure, and therefore net operating profits

adjusted taxes (NOPLAT) is equal to free cash flow for

business that does not grow. In effect, the first contrib

is calculated as NOPLAT divided by the companys co

capital.

7 This can be achieved without an explicit discounted c

flow model by using, for example, the value driver form

derived by Tom Copeland, Tim Koller, and Jack Murrin

Valuation: Measuring and Managing the Value of

Companies, third edition, New York: John Wiley & Son

2000.

8 For a company that grows more slowly than GDP, this

value will be negative.

MoF

All P/Es are not created equal

While more sophisticated

analyses are sometimes

appropriate, executives can

learn a lot about their P/E

multiple with this simple

three-part model.

-

8/14/2019 MoF Issue 11

18/24

Putting value back

in value-based

management

Value-based management programs focus

too much on measurement and too little on

the management activities that create

shareholder value.

Value-based management (VBM) burst

onto the scene a decade ago with a

revolutionary promise: a company that

traded in traditional management

approaches in favor of VBM could align its

aspirations, mind-set, and management

processes with everyday decisions that truly

add shareholder value. Name the initiative

investing in a new project, say, or spinning

off a subsidiary, or implementing new

customer-service guidelinesandmanagement could not only pinpoint better

projects but also better understand the value

they would create for shareholders. Indeed,

well-implemented VBM programs typically

deliver a 5 to 15 percent increase in

bottom-line results.

Sadly, even as VBM has evolved, most

programs are notable more for their

implementation shortfalls than for theirsuccesses. In our ongoing work and

discussions with executives, we have begun

to identify a few common pitfalls that have

repeatedly plagued underperforming

VBM programs going back years as well as

some newer wrinkles that stanch the benefits

that VBM can deliver. Weve also developed

16 | McKinsey on Finance | Spring 2004

Richard J. Benson-

Armer, Richard F.

Dobbs, and

Paul Todd

an anecdotal view of how the most

successful practitioners push the principles

of VBM to achieve its real promise for

shareholders.

Simply put, ailing VBM programs typically

settle for merely measuring value creation i

business initiatives, while successful

approaches push to link t ightly the

measurement to how the business can be

improved. For example, some companies

mechanically measure historical

performance but then fail to apply what

theyve learned to the strategies from which

value should flow. Most also neglect to

account for future growth and

sustainability. Others make this important

link but then set targets in ways that fail to

mobilize the troops needed to make VBM

pay off. Still others go to great lengths to

implement VBM programs but then relegat

them to the finance department, where they

languish without the commitment of senior

level management.

Troubled VBM programs do not necessarily

manifest all these symptoms at once. In ourexperience, however, the vast majority

suffer from at least one. Moreover, the best

practitioners have learned to overcome them

and can provide guidance about how to

push VBM to better fulfill its potential.

Missing the link between

measurement and value

The original breakthrough of value-based

management was to draw attention to thefailure of traditional accounting measures,

such as net income and earnings per share,

to account for the cost of capital.

Traditional managers focused far more

intently on improving cost and gross

margin and paid little if any attention to

the capital invested in the business. As a

-

8/14/2019 MoF Issue 11

19/24

Putting value back in value-based management

result, it was common to find projects in

which much of the capital deployed in

businesses was wasted.

As managers focused on value creation and

the true economic cost of capital deployed

in the business, VBM proponents

introduced metrics to measure a businesss

or programs value, including return oninvested capital (ROIC), economic profit,

cash flow return on investment (CFROI), or

economic value added (EVA).1 The

advantages of different measures vary

(Exhibit 1), but they all attempt to

recognize the cost of capital in the

benchmarks managers use to gauge the

value their decisions create.

Yet many companies fall into the trap offocusing their measurement too much on

historical returns, which are easily

quantified, and too little on more forward-

looking contributors to value: growth and

sustainability. For instance, one consumer

goods company (Exhibit 2) was able to

demonstrate strong economic returns for

five years as measured by economic prof

But because the company delivered its

growth by increasing prices, it ultimately

damaged its customer franchise and cou

not sustain its growth rate.

Companies that apply VBM at a more

advanced level move beyond measuremen

help the management team focus on thelevers that can be used to improve the

business. The best programs use value tre

to identify underlying drivers of operatin

value. These have long been at the core of

VBM theory, but we find that they are sti

conspicuously missing in many applicatio

Savvy VBM practitioners use these trees

identify areas of improvement, pushing d

into a businesss operating performance comparing it with others to create clear

benchmarks. These benchmarks can also

pegged to the performance of peers outs

the company, or to the performance of

similar internal businesses. One particula

informative and credible internal benchm

comes from analyzing the historical

e x h i b i t 1

Metrics designed to measure value have strengthsand weaknesses

1 EBITDA = earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, amortization; ROS = return on sales; EPS = earnings per share; ROE = return on equity; ROCreturn on capital employed; ROIC = return on invested capital; ROA = return on assets; EVA = economic value added; DCF = discounted cash flow; IRinternal rate of return; CFROI = cash flow return on investment

Source: McKinsey analysis

Traditional P&L and balance sheet approaches

Revenues EBITDA1

Net income

Book value ROS1

EPS1 (diluted or not)

Relevance for management declining, but stillwidely used by companies for communication toinvestors (e.g., EPS)

Economic cost of the capital invested ignored

Growth, long-term performance, and sustainabilitynot taken into account

Value creation: historical metrics

Return ratiosROE1ROCE,1 ROIC1

ROA1 Economic profit or EVA1

Widely used concepts orientatedtowards taking into account theeconomic cost of the capital in thebusiness

Growth, long-term performance, andsustainability not taken into account

Value: forward-looking metrics

DCF1-value Discounted EVA1

IRR1

CFROI1

Required for active management ofcompanys value

Explicit consideration of growth andlong-term impact of decisions

High correlation to market value ofcompany

Much harder to measure accuratelyand so can be gamed

-

8/14/2019 MoF Issue 11

20/24

18 | McKinsey on Finance | Spring 2004

performance of the same business over time.

For example, one processing companys

analysis found that daily performance alone

varied so widely that the management team

didnt need to look for outside benchmarks.

Instead, they could improve the overall

performance of the company enough just by

focusing their efforts on the levers that led

to the most severe underperformance on

bad days.

The error in focusing on targets

rather than how they are setA second common VBM pitfall stems from

the way executives set performance targets

and hand them down to the individuals

responsible for meeting them. These targets

may seem perfectly reasonable to the

managers who set them, but they often

appear arbitrary and unrealistic and convey

little sense of ownership to the teams that

receive them. In our experience, only when

those assigned to meet the targets alsoactively help in setting them is a company

likely to generate the understanding and

commitment needed to deliver outstanding

performance (Exhibit 3). Indeed, we find

the process of setting targets to be the

single biggest factor in delivering superior

VBM performance.

Consider the experience of one global

consumer goods company. When the

corporate technical manager ordered that al

the companys bottling lines should achieve

75 percent operating efficiency, regardless o

their current level, some plant operators

rebelled. Operators at one US plant,

concluding that at 53 percent their plant wa

running as well as it had ever run, worked

only to maintain performance at historical

levels. Yet after the plant launched an

inclusive process to permit the operators to

set their own performance goals, they raised

performance levels above the 75 percent

target over a period of only 14 months.

The most effective VBM programs fine-tun

this dynamic even more. As they set targets

some build in a challenge from peers

running similar businesses. This approach

helps to stretch targets, to highlight

accountability in view of peers, and to

create the sense of commitment and

purpose that comes from collaborating on

tough issues. Because colleagues running

similar businesses will be familiar with all

the opportunities for improvement, theywill be much more effective than line

managers at providing such challenges.

Companies that have excelled at VBM

programs arrange them not only on overall

profitability but also on capital expenditure

growth, pricing, and costsas well as

performance during the year. Others create

formal processes that encourage mutual

support among colleagues to improve the

performance of the business. At one ofCanadas largest privately held companies,

for example, stronger performers are

explicitly assigned to help their colleagues

who are not performing as well.

Or consider how one chemical company

designed a more effective way to review

e x h i b i t 2

Financial measures alone are inadequate

Economic profit went up, to a point . . .Year 1 = 100

. . . but proved unsustainable, as marketshare steadily declined, %

Source: McKinsey analysis

160

120

200

Year Year

80

40

01 3 5 72 4 6

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

1 3 5 72 4 6

Profit growth dueto price increases

-

8/14/2019 MoF Issue 11

21/24

performance. A year after introducing a

VBM approach to make reported data

more transparent, the company had yet to

see the improvements it expected. Worse,

nearly everyone in the organization

recognized that official discussions about

performance were something of a sham.

Some managers misrepresented reportsof their actual performance in order to

create the appearance of meeting targets;

others built enough slack into future

performance targets to make sure they

would easily be met.

The companys response: change the review

process. What had been a one-on-one

review involving the division head and unit

leader became a broader discussion betweenthe division head and all unit leaders

together. And rather than simply reviewing

the data, the meeting focused on the most

important lessons from the previous

reporting period, as well as the greatest

risks and opportunities expected to appear

in the coming reporting period. Emphasis at

the meeting shifted away from individua

successes and failures to a combination o

shared lessons and problem solving on

future risks and opportunities.

Next the company introduced a series of

peer meetings among unit leaders withou

the division heads present. These meetinaimed to review plans and identify risks

opportunities in order to set priorities fo

allocating capital and resources. In the fi

year of operating under the new process

capital outlays dropped 25 percent and

underlying profits, adjusted for the usual

modulations of the business cycle, rose b

10 percent.

Not ingraining VBM in day-to-dbusiness processes

Setting targets and committing to meet th

is one thing. Its another to make sure tha

performance targets are acted upon. This

process happens by making certain that

specific individuals are accountable and

responsible for making decisions and by

Putting value back in value-based management

e x h i b i t 3

Involve managers early in KPI1 definition process to ensure acceptance and accountability

Success factor This Not this

Guided self-discovery Managers discover the key value drivers and KPIs forthemselves

The process, rigor, and insights will be shared between

units

External team (or a staff team) doesthe analysis and develops value driversand KPIs

Strong senior management leadership Management actions and messages emphasize valuecreation and value-based shaping of the management

agenda

Senior managers, publicly or privately,communicate or act in ways that do notreflect the value drivers and KPIs

Inclusive and open communication Relevant staff is involved both in analysis and rollout,

with a clear understanding of the ultimate objective

Staff is told what the new value driversand KPIs are

Fact-based debate and challenge Discussions and decisions are based on facts Discussions and decisions are based onpersonal preferences and past actions

Link to real deliverables KPI framework leads to clear assignment of

accountabilities for targets and actions

KPI work is done separately from thebudget and targeting processes

1 Key performance indicator.

Source: McKinsey analysis

-

8/14/2019 MoF Issue 11

22/24

20 | McKinsey on Finance | Spring 2004

guaranteeing a link between performance

and an individuals evaluation process.

One energy company, for example,

implemented a VBM program that seemed

to have all the right parts. But management

then failed to carry it over from a discrete

program in the finance department to

engage the

entire company.

This result was

despite the fact

that the

companys

finance team

developed a

first-rate

scorecard covering financial performance,

operating drivers, organizational health,

and customer service. Nearly a year later,

there was no discernible impact. Beyond

top-level conversations, few of the

companys managers used the scorecard

some didnt even know what it was. They

had had no involvement in the programs

development, little understanding of why

the new scorecard was necessary, and noincentive to use it. The few that did use it

found that targets regularly were missed.

Some companies overcome this pitfall by

using a formal performance contract to

explicitly link the key performance

indicatorssuch as sales, profit margin,

return on investment, and customer

satisfactionwith roles such as sales

manager, business unit manager, financemanager, and call-center manager

respectively. This link forces an explicit

conversation to take place about whether

roles and decision rights are correctly lined

up. Other companies link their people-

evaluation system to hitting targets, with

explicit rules about dismissals for

individuals who fail to meet their targets

more than once. By tying performance

evaluation and compensation to individual

objectives, performance can also be aligned

with the objectives of the VBM program.

A rule of thumb: until a VBM program is

an integral part of how a company

manages, it will always be simply

something else to do and will inevitably

fail as employees continue to perform as

they always have. Finance department inpu

is essential, for example, but delegating

VBM to the finance department as a

discrete, isolated program is a surefire way

to snuff its potential.

Too few VBM programs have fulfilled their

early promise. But recognizing common

patterns in programs that have gone awry i

a first step in moving VBM closer to its goa

to help line managers deliver better

performance for shareholders.

Richard Benson-Armer (Richard_Benson-

[email protected])is a principal in McKinseys

Toronto office.Richard Dobbs (Richard_Dobbs

@McKinsey.com)is a principal in the London office,

wherePaul Todd([email protected]) is an

associate principal. Copyright 2004 McKinsey &

Company. All rights reserved.

The authors wish to acknowledge the valuable

contributions of Joe Hughes, Tim Koller, and

Carlos Murrieta to the development of this article.

1 EVA is a registered trade mark of Stern, Stewart & Co.,

New York, and is synonymous with the more generic term

economic profit.

2 Tom Copeland, Tim Koller, and Jack Murrin, Valuation:

Measuring and Managing the Value of Companies, third

edition, New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2000.

MoF

Until a VBM program is an

integral part of how a company

manages, it will always be

simply something else to do

and will inevitably fail.

-

8/14/2019 MoF Issue 11

23/24

AMSTERDAANTWER

ATHENATLANT

AUCKLANAUSTI

BANGKOBARCELON

BEIJINBERLI

BOGOTBOSTO

BRUSSELBUDAPES

BUENOS AIRE

CARACACHARLOTTCHICAG

CLEVELANCOLOGN

COPENHAGEDALLA

DELHDETRO

DUBADUBLI

DSSELDORFRANKFUR

GENEVGOTHENBUR

HAMBURHELSINK

HONG KONHOUSTOISTANBUJAKART

JOHANNESBURKUALA LUMPU

LISBOLONDO

LOS ANGELEMADRIMANIL

MELBOURNMEXICO CIT

MIAMMILA

MINNEAPOLMONTERRE

MONTRAMOROCC

MOSCOW

MUMBAMUNIC

NEW JERSENEW YOR

OSLPACIFIC NORTHWES

PARPITTSBURG

PRAGUQATA

RIO DE JANEIRROM

SAN FRANCISCSANTIAG

SO PAULSEOU

SHANGHASILICON VALLE

SINGAPORSTAMFORSTOCKHOLM

STUTTGARSYDNE

TAIPTEL AVI

TOKYTORONT

VERONVIENN

WARSAWWASHINGTON, D

ZAGREZURIC

-

8/14/2019 MoF Issue 11

24/24

Copyright 2004 McKinsey & Company