Modern Journal of Studies in English Language Teaching and ... · 4/1/2020 · specific frameworks...

Transcript of Modern Journal of Studies in English Language Teaching and ... · 4/1/2020 · specific frameworks...

VOLUME 2 ISSUE 1 APRIL 2020

Modern Journal of Studies in English Language Teaching and Literatue Vol. 2 Issue 1. April 2020.

Modern Journal of Studies in English Language Teaching and Literature

Volume 2 Issue 1 April 2020

Chief Editor

Leah Gustilo, Ph.D.

Co-Chief Editor

Rouhollah Askaribigdeli

Modern Journal of Studies in English Language Teaching and Literatue Vol. 2 Issue 1. April 2020.

Table of Contents

A Genre-based Rubric for Peer Feedback

Farhad Jafari Basmenj 1

Differences in Teaching Styles and Oral Language Proficiency of

Non-native English Speaker Teachers: As Perceived by the Iranian EFL Students

Mohammad Javadi 10

The morphology and semantics of conjuncts: The case of MA theses

in the Philippine setting

Jennifier T. Diamante 31

Rhetorical Structure of Research Acknowledgment Sections

in Master’s Thesis Manuscripts

Elizabeth B. Alibangbang, MALT

Donnie M. Tulud, Ph.D. 51

Characterizing the language features and rhetorical moves of argumentative essays

written by Filipino ESL senior high school writers

Marites B. Querol

Marilu Rañosa Madrunio, Ph.D. 62

Modern Journal of Studies in English Language Teaching and Literature Vol. 2 Issue 1. April 2020

1

A Genre-based Rubric for Peer Feedback

Farhad Jafari Basmenj University of British Columbia

Abstract

Peer feedback in writing is considered an important stage of pedagogy. Peer feedback in L2 writing has been investigated through different lenses. Although a genre-based rubric for writing assessment is offered in the literature of feedback, a well-defined, principled and expert-like rubric with genre specifications is missing from peer feedback literature. This study offers a literature review of peer feedback literature, pinpoints the gaps, and provides a new, student-friendly 3x3 rubric for argumentative genre in writing through the amalgamation of frameworks in the literature. The pedagogical implication and application stages of the new genre-based rubric are discussed at the end. Keywords: Genre, rubric, argument writing, peer feedback Feedback: Expert and Peer

Feedback is an important part of teaching which can reinforce the input and help with the prevention of wrong output fossilization. It is that stage of the pedagogy wherein learners negotiate meanings with their experts or their peers, and their learning consolidates. Corrective feedback is defined as “responses to a learner’s nontarget-like L2 production” (Li, 2010, p. 309) and has been empirically shown to have positive impacts on students’ writings (Bitchener & Ferris, 2012; Bruton, 2009; Greenslade & Felix-Brasdefer, 2006; Hyland, 2003). Often treated as ancillary to instructor feedback, peer feedback has also drawn a lot of attention (Hu & Lam 2010; Liu 2012; Yang 2011; Yu & Lee 2014, 2015; Zhu &Mitchell 2012; Zhao 2010, 2014). Peer feedback is “the use of learners as sources of information and interactants for each other in such a way that learners assume roles and responsibilities normally taken on by a formally trained teacher, tutor, or editor in commenting on and critiquing each other’s drafts” (Liu & Hansen, 2002, p.1). In the literature, peer feedback has been studied from different perspectives with diverse methodological approaches in different contexts: comparisons between instructor and peer feedback with mixed findings about their efficacy and superiority (Birjandi &Tamjid, 2012; Chang, 2012; Chen, 2010; Lam 2013; Memari Hanjani, 2013; Ruegg, 2014), its benefits for feedback givers (Berggrenn 2015; Rosalia 2010), computer-mediated peer feedback and L2 earners’ perceptions of it (Ciftci & Kocoglu, 2012; Chang, 2012, Chen, 2012), the role of training on writing quality (Rahimi 2013; Yang & Meng 2013), and students’ level and peer feedback (Chong, 2017).

One problem about the current literature is that it either does not provide a well-defined,

descriptively detailed rubric for peer feedback (Chong, 2017; Diab, 2010; Hu & Lam, 2010; Lam, 2013) or, if it does, it is heavily embedded in the traditional holistic binary of micro-macro features of the text, and is devoid of any genre-based specifications and guidelines for learners (Birjandi & Tamjid, 2012; Vorobel & Kim, 2017). The penury of rubric in literature emanates from a reductionistic view that strips writing of its generic properties. Writing in the

Modern Journal of Studies in English Language Teaching and Literature Vol. 2 Issue 1. April 2020

2

literature of peer feedback is hardly considered as a genre, and the instruction and training for feedback is rarely based on the rigors of genre. One interesting study on feedback is Anson and Anson’s (2017) investigation of a corpus of 50000 peer responses. Their study results confirm that an “expert principled response to writing” is concentrated on audience, organization, focused support, purpose, idea development and coherent structure, features hardly explored in peer feedback rubric and literature. It seems that genre-based pedagogy and SFL (Systemic Functional Linguistics) could bridge this gap in peer feedback by the provision of a framework which is inherently grounded on the rules of a genre. In the rest of this article, a basic definition of genre is provided, and conceptualization of argumentation as a genre is explained. A peer feedback rubric for argument genre is developed through integration of three frameworks in the literature, and a new version of Teaching and Learning Cycle (TLC) pedagogy with the component of peer deconstruction is provided at the end.

Genre and argumentation

Genre is “a term for grouping texts together, representing how writers typically use

language to respond to recurring situations” (Hyland, 2008, p. 544). Writing such texts is a practice based on a series of conventions that communities of practice expect of a writer. The author has a purpose, and the moves that s/he follows should align with the expected conventions. Genre-based writing instruction has many advantages: It is explicit and clear, supportive (in that it scaffolds); systematic (by providing a framework), critical (as it shows resources of discourses, and raises consciousness (Hyland, 2008). And perhaps the biggest advantage of genre is that it is recognizable by the “communities of practice” (Wenger, 1998), and that the writer gains a sense of belonging to the community through following the conventions of the genre (Hyland, 2008). The key principle in teaching through genres (genre-pedagogy) is raising students’ awareness of textual features and grammatical repertoire that the writer uses to achieve a particular purpose. Here, grammar does not signify the rules that exist independent of texts, but the rhetorical features that bind the text together and help the writer communicate his purpose.

The prevalence of argumentation in SLW (second language writing), evidenced by its

appearance in proficiency exams such as IELTS and TOEFL, makes it an important genre to consider in EAP/ESP contexts. As Hirvela (2017) observes, argumentation in the literature is conceptualized as either a form of reasoning (Toulmin, 2001) or inquiry (Kuhn, 2005). In argumentation as a form, the focus is on logic and the reasoning through which the writer renders a persuasive and convincing end product. In inquiry, argumentation is utilized to deepen analytic skills, a vehicle to solve problems. It appears that both concepts of arguments can be useful in EAP/ESP contexts.

Genre-based rubric

Fang and Wang (2009) critique the 6-straits writing Rubric, prevalent in American schools, on the basis that it is neither objective nor exact. Furthermore, according to them, the rubric is insensitive to genre, functions, and register requirements. Although their critique is targeted at rubric for teachers, as the review of above literature on peer feedback demonstrated, lack of genre-specific rubric is an obvious gap in the literature. Thus, it appears that a generic framework (for argumentative genre) for peer feedback can be devised with reference to literature of genre.

The genre-based rubric has been put forward in several studies. Humphrey et al. (2010) offer a 3x3 framework in the hope that it can be used to “inform the development of genre-

Modern Journal of Studies in English Language Teaching and Literature Vol. 2 Issue 1. April 2020

3

specific frameworks for analysing, modelling, and assessing texts in particular disciplines” (p. 186). It is a “principled overview of resources” to “make it explicit the expectations of academic writing” (Humphrey et al., p. 187). It is a 9-square matrix composed of 3 metafunctions of language (ideational, interpersonal and textual) and 3 linguistic strata (social activity, discourse semantics, and grammar and expression). Ideational meaning represents “experience and connect events” (field), interpersonal metafunctions “negotiate attitude and relationships” (tenor), and textual meaning “weave ideational and interpersonal meanings into a coherent whole” (mode) (Humphrey et al., p. 191). As for stratification, social activity refers to the overall purpose and the staged goals of the genre realized though social registers such as field, tenor and mode, often assessed by content lecturers. At discourse semantics strata, students often use the repertoire of linguistic patterns which construe meaning within phases and paragraphs. The grammar and expression strata refer to linguistic resources which link clauses within sentences. They use the 3x3 framework to analyze a report summary genre in biology discipline. However, the framework, as they suggest, can be exploited and adapted to the requirements of other disciplines. Students can also be scaffolded to create their own resources.

Another less elaborate and more practical framework is the one provided by Mahboob

(2015). Drawing on the findings of SLATE project (Mahboob, Humphrey, Webster, Wong and Wong, 2010), Mahboob’s (2015) model proposes the idea of cohesion and coherence in feedback. The project was an online language and literacy program to help students ameliorate literacy skills in core academic units and was founded on Systematic Functional Linguistics (SFL), genre pedagogy (Rose and Martin, 2012) and Teaching Learning Cycle (TLC). According to Mahboob (2015), cohesion refers to the “purpose, audience and organization” of feedback, whereas coherence is achieved “when various instances … on a student’s text work together to scaffold a student into developing a deeper understanding of particular (selected) issues in their writing” (p. 358). He provides a framework and an assessment rubric where three different strata of language are addressed in the provision of cohesive feedback: Purpose and structure of the text (Criteria A), Development of meanings across paragraphs (Criteria B), and Grammar and expression (Criteria C) (p. 359). Findings of SLATE project suggested that Criteria A should be given priority followed by Criteria B and then Criteria C. Coherence, on the other hand, refers to the continuum of explicitness in the feedback and the rationale that the teacher provides. In a feedback, the teacher can provide an overtly explicit remark (such as provision of a correct grammatical form, or another word) or be implicit by just asking question and eliciting a correct form. In doing this, the teacher can also point out to the underlying linguistic reasons why a given form is not allowed in a genre.

Pessoa, Mitchell and Miller (2017) provide a more elaborate framework based on genre

pedagogy and SFL. In their examination of university students’ history argumentative essays, they adapt the 3x3 framework originally proposed by Humphrey et al. (2010). 3x3 is an educational toolkit which allows instructors a better understanding of important features of an academic genre and helps them “consider subtle ways that student writing does and does not meet genre expectations” (Pessoa et al., 2017, p.46). This toolkit utilizes three SFL-based metafunctions of language: ideational (resources to expand the form knowledge of the content), interpersonal (resources to posit an authoritative voice) and textual (resources to organize a clear text). These three metafunctions are studied at 3 levels of text, paragraph and sentence. The ideational meaning is concerned with writing in clear stages in response to the prompt “with accurate, relevant, and sufficient content from the source text(s)” (p. 48). The information should proceed from general to specific logically with quotes from the text. Interpersonal meaning refers to the stance that the writer assumes in defending and reinforcing

Modern Journal of Studies in English Language Teaching and Literature Vol. 2 Issue 1. April 2020

4

an overarching proposition in order to persuade the reader. The linguistic resources such as tentativeness, counterarguments, accepting other perspectives or justifying one’s own view are considered in interpersonal analysis. The textual analysis is concerned with “the organization of the text and its effectiveness in following, predicting, signposting, and scaffolding the writer’s ideas” (p. 48). Although their framework is aligned with a more generalist rubric of the history instructor (based on Argument, Evidence, Clarity, Synthesis and Analysis), it explicitly makes reference to the linguistic requirements for the expectations of a genre.

The following rubric is based on the three frameworks and is intended to use for peer

response purposes. Students can make use of this rubric to comment on each other’s writings.

Whole text Paragraphs sentences/Clauses Ideational Meanings

Ideas are developed to form an analytic framework.

There is a main claim and sub claims to support it.

Noun groups in topic sentences.

The answer to the prompt is consistent.

The information moves from general to specific, point to elaboration, evidence to interpretation, claim to evaluation.

Technical and formal vocabulary Verb tenses are consistent.

Interpersonal Meanings

Answer to the question is convincing and critical. The position is reinforced, justified and defended to persuade the reader.

Authoritative sources are used to support the claim.

• Interpersonal objective metaphors (It is clear instead of I think)

• Subject and verb agreement The language is impersonal and objective. Response to the question is persuasive and shows a critical stance.

Writer’s stance is developed through patterns of evaluation.

• Modality (may, can, might), hedging devices (probably, likely) and booster (clearly, obviously) are used appropriately.

• The transitional markers are used to create a logical flow:

• Add (besides, in addition, etc.) • Compare and concession

(whereas, however, although, conversely)

• Justification (since, because, for the same reason)

• Example (for instance, in this situation, on this occasion)

• Summarize (to sum up, therefore, accordingly)

• Correct use of conjunctions • Justification (because)

Textual Meanings

The text has an introduction, body and conclusion paragraphs.

Topic sentences in sub-claims match the ideas in the introduction.

• Articles are used properly. • Active and passive voice are

used properly The text is cohesive and signposted. Cohesive devices create a logical

flow of information. Information flows from abstract to concrete.

• Pronouns are used properly in referencing.

• Punctuation and spelling are used properly.

Figure 1. Argumentative Genre Peer Feedback Rubric

The rubric in Figure 1 is an amalgamation of three frameworks intended to provide L2

writers with a more student-oriented rubric. Three levels of ideational, interpersonal and textual levels are the prominent features of this framework. The three traditional rhetorical moves of logos, ethos and pathos are included in the interpersonal at both whole text and paragraph levels. Through these moves, the writers first establish an authoritative claim and sets out to persuade the reader though evaluation and engagement. Micro features of the text such as the hedgers, booster and transitional markers are placed at sentence level. Although this adapted framework lacks the elaborateness of original frameworks, it should not be forgotten that it is designed for students who are not expert in either genre or its SFL-based grammar. It is also assumed that students are already familiar with the terminology of genre pedagogy; and in

Modern Journal of Studies in English Language Teaching and Literature Vol. 2 Issue 1. April 2020

5

order to achieve this purpose, adoption of Teaching and Learning Cycle in pedagogy is imperative.

Teaching and Learning Cycles

In order to familiarize students with the grammar of a text, genre-based pedagogy follows Teaching Learning Cycle (TLC) (de Oliveira & Lan, 2014; Feez, 2002; Rose & Martin, 2012). TLC comprises three phases: first, a text is deconstructed with the students; second, a new text is jointly constructed with the teacher scaffolding the students; and third, students are encouraged to construct their own text. The use of the word “construct” instead of “produce”, “create”, or “write” is noteworthy here since it evokes the construction of a building with an architectural plan in which everything is at work in order to achieve the purpose of constructing a building similar to other structures. The teacher presents a model, argumentative genre for example, and analyzes it. During the Deconstruction phase, the focus is on the “genre’s social purpose and typical organizational structure” at a whole text followed by decoding the text at a sentence-level during which the resources that help create the content, meet audience expectations, and present a coherent message are illuminated (Ramos, 2019, p 51). At this stage, the teacher builds metalinguistic awareness through introducing SFL-based terms such as nominalization and processes, strong modality, causal links, conjunctions, synonyms and referents. During the Joint Construction, the teacher scaffolds the students to write a generic text by providing academic language resources. This stage involves collaboration and is another opportunity for a discussion on how the academic and linguistic resources help realize a coherent message. Students write their own genre-based text at the Independent Construction stage since they now have a growing knowledge about textual functions, rhetorical features and linguistic resources of a genre. Ramos (2019) practiced TLC with ELL students from different backgrounds in a secondary school setting. Her experience showed that students managed to master academic resources in argumentative genre, and that their language shifted away from conversational register in their writing to more academically genre-endorsed style.

TLC has slightly different versions, too. For instance, in de Oliveira (2017), the element

of “collaborative construction” has been added to the cycle on the rationale that it is “a bridge between the joint construction and independent construction phases” (p.3). The collaborative construction follows joint construction during which students discuss, negotiate, brainstorm and write together in groups (de Oliveira, 2017). This new phase could be particularly useful in EFL contexts where students’ exposure to language outside classroom is severely constrained and this intermediary stage between joint construction and independent construction can scaffold students with further exposure to genre requirements. In Feez (2002), the process comprises 5 stages: a) building the context, b) modelling and deconstructing the text c) joint construction of the text d) independent construction of the text and e) linking related texts. Different from other TLC formats is the inclusion of the first and last stages. In the first stage, the teacher “designs opportunities for learners to experience and explore the cultural and situational aspects of the social aspect of the target text” (p. 66) through activities such as listening or chatting to others, brainstorming, video, realia and pictures. In fact, before the text, the teacher at this stage activates the schemata and prepares them for the next stage. In linking related texts, students compare texts and discuss their different effectiveness.

Modern Journal of Studies in English Language Teaching and Literature Vol. 2 Issue 1. April 2020

6

Figure 2. Integrated Model

For the purpose of this study, Feez’s (2002) TLC version is integrated with that of de

Oliveira (2017) and a new phase is added. The new integrated model comprises six stages: Building the Context, Deconstruction, Joint construction, Collaborative Construction, Independent Construction, Peer deconstruction (Figure 2). The new model borrows Building the Context from Feez’s (2002) and Collaborative Construction from de Oliveira (2017). The rationale for the integration of Building the Context is that it is “foundation step for second language learners” (p.66). Here, the “teacher designs opportunities for learners to experience and explore the cultural and situational aspects of the social context of the target text” (p. 66). These activities may include brainstorming, reading and discussing relevant material, discussing pictures, guided research and fieldtrips. In order to train L2 learners to use the rubric, it seems scaffolding at every stage of the lesson is indispensable. Scaffolding is realized at every stage of the new model through the instructor at the Building the Context, Deconstruction, Joint Construction, the peer at Collaborative Construction and Peer Deconstruction, and the rubric at all levels (Except Creating the Context). The elements of the new rubric need to be repeated at every stage of a genre pedagogy, and in the new model this is realized in all five stages except for Building the context. In the peer Deconstruction phase, students’ writings are deconstructed by their peers through comments on the text scaffolded by a rubric. In fact, this stage is the mirror phase of Deconstruction where the instructor analyzes different features of the text with students. Here, it is not the teacher but the learner-expert who deconstructs the text written by their peers. This Peer Deconstruction stage has several advantages: the generic features of a student-produced-text will be critically analyzed by students. In this way, the peer feedback offers further opportunities for students to engage with the genre. Since at this stage each learner has access to the rubric, the constant reference back and forth the text and the framework will consolidate the generic features. Furthermore, the students will assume the role of an expert and this expertise is a guarantee of the achievement of learning goals. Finally, students will obtain a sense of agency as the peer feedback in the model not only provides an opportunity to grapple with the generic features but also transpositions them from peripheral to full participation in the practice of text construction.

Modern Journal of Studies in English Language Teaching and Literature Vol. 2 Issue 1. April 2020

7

References Anson, I. G., & Anson, C. M. (2017). Assessing peer and instructor response to writing: A

corpus analysis from an expert survey. Assessing Writing, 33, 12-24. doi:10.1016/j.asw.2017.03.001

Berggren, J. (2015). Learning from giving feedback: A study of secondary-level students. ELT Journal, 69, 58–70.

Birjandi, P., & Hadidi Tamjid, N. (2012). The role of self-, peer and teacher assessment in promoting Iranian EFL learners’ writing performance. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 37 (5), 513–533.

Bitchener, J. & Ferris, D. R. (2012). Written corrective feedback in second language acquisition and writing. New York: Routledge.

Bruton, A. (2009). Improving accuracy is not the only reason for writing, and even if it were. System, 37(4), 600-613. doi:10.1016/j.system.

Chang, C. F. (2012). Peer review via three modes in an EFL writing course. Computers and Composition 29 (1), 63–78.

Chen, C. W. (2010). Graduate students’ self-reported perspectives regarding peer feedback and feedback from writing consultants. Asia Pacific Education Review, 11, 151–158.

Chen, K. T. C. (2012). Blog-based peer reviewing in EFL writing classrooms for Chinese speakers. Computers and Composition 29 (4), 280–291.

Chong, I. (2017). How students' ability levels influence the relevance and accuracy of their feedback to peers: A case study. Assessing Writing, 31, 13-23. doi:10.1016/j.asw.2016.07.002

Ciftci, H. & Z. Kocoglu (2012). Effects of peer e-feedback on Turkish EFL students’ writing performance. Journal of Educational Computing Research 46 (1), 61–84.

de Oliveira, L. C. (2017). A genre-based approach to L2 writing instruction in K-12. TESOL Connections, July 2017. http://newsmanager.commpartners.com/tesolc/ issues/2017-07-01/3.html

de Oliveira, L. C., & Lan, S. W. (2014). Writing science in an upper elementary classroom: A genre-based approach to teaching English language learners. Journal of Second Language Writing, 25(1), 23–39.

Diab, N. M. (2010). Effects of peer- versus self-editing on students’ revision of language errors in revised drafts. System 38, 85–95.

Fang, Z., Wang, Z., & others. (2011). Beyond rubrics: Using functional language analysis to evaluate student writing. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 34(2), 147-165.

Feez, S. (2002). Heritage and innovation in second language education. In A. M. Johns (Ed.), Genre in the classroom: Multiple perspectives (pp. 43–69). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Greenslade, T.A. & Felix-Brasdefer, J.C. (2006). Error correction and learner perceptions in L2 Spanish writing. In: Klee, C.A., Face, T.L. (Eds.), Selected Proceedings of the 7th Conference on the Acquisition of Spanish and Portuguese as First and Second Languages (pp. 185–194) Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Proceedings Project. ,

Hirvela, A. (2017). Argumentation and second language writing: Are we missing the boat? Journal of Second Language Writing, 36, 69–74.

Hu, G. & Lam, S. T. E. (2010). Issues of cultural appropriateness and pedagogical efficacy: Exploring peer review in a second language writing class. Instructional Science, 38, 371–394.

Modern Journal of Studies in English Language Teaching and Literature Vol. 2 Issue 1. April 2020

8

Humphrey, S. Martin, J. R., Dreyfus, S, & Mahboob, A. (2010). The 3x3: setting up a linguistic toolbox for teaching and assessing academic writing. In Mahboob, A & Night, N. (Eds.), Appliable Linguistics, (pp. 185-199). London: Continuum.

Hyland, F. (2003). Focusing on form: student engagement with teacher feedback. System, 31, 217–230.

Hyland, K. (2008). Genre and academic writing in the disciplines. Language Teaching, 41, 543-562 doi:10.1017/S0261444808005235

Johnson, K. G. (2012). Peer and self-review: A holistic examination of EFL learners’ writing and review process. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Arizona.

Kuhn, D. (2005). Education for thinking. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Lam, R. (2013). The relationship between assessment types and text revision. ELT Journal, 1–

13. Li, S. (2010). The effectiveness of corrective feedback in SLA: A meta-analysis. Language

Learning, 60 (2), 309–365. Liu, J. & Hansen, J.G. (2002). Peer response in second language writing classrooms. Ann

Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Liu, J. (2012). Peer response in second language writing. In C. Chapelle (Ed.), The

encyclopedia of applied linguistics. Wiley, Blackwell, 2012. Mahboob, A. (2015). Understanding and Providing “Cohesive” and “Coherent” Feedback on

Writing. Writing & Pedagogy, 7(2/3), 355–376. https://doi-org.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/10.1558/wap.v7i2-3.26461

Memari Hanjani, A. (2013). Peer review, collaborative revision, and genre in L2 writing. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Exeter.

Miller, R. & Pessoa, S. (2016). Where is your thesis statement? Identifying organizational challenges in undergraduate student argumentative writing. TESOL Journal, 7(4), 847-873.

Pessoa, S., Mitchel, T., & Miller, R. (2017). Emergent arguments: A functional approach to analyzing student challenges with the argument genre. Journal of Second Language Writing, 38, 42-55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2017.10.013

Rahimi, M. (2013). Is training students’ reviewers worth its while? A study of how training influences the quality of students’ feedback and writing. Language Teaching Research, 17, 67–89.

Ramos, K. (2019). A genre-based approach to teaching argument writing. In L. C. de Oliveira et al. (Eds.), Teaching the Content Areas to English Language Learners in Secondary Schools, (pp. 49-63). Cham: Springer.

Rosalia, C. (2010). EFL students as peer advisors in an online writing center. Ph.D. dissertation, New York University.

Ruegg, R. (2014). The effect of peer and teacher feedback on changes in EFL students’ writing self-efficacy. The Language Learning Journal. Available at www.tandfonline.com/, 1–18.

Toulmin, S. (2001). Return to reason. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Vorobel, O., & Kim, D. (2017). Adolescent ELLs' collaborative writing practices in face-to-

face and online contexts: From perceptions to action. System, 65, 78-89. doi:10.1016/j.system.2017.01.008

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Yang, Y. F. & W. T. Meng (2013). The effects of online feedback training on students’ text revision. Language Learning &Technology 17 (2), 220–238.

Yang, Y. F. (2011). A reciprocal peer review system to support college students’ writing. British Journal of Educational Technology 42 (4), 687–700.

Modern Journal of Studies in English Language Teaching and Literature Vol. 2 Issue 1. April 2020

9

Yu, S. & I. Lee (2014). An analysis of EFL students’ use of first language in peer feedback ofL2 writing. System 47, 28–38.

Yu, S. & I. Lee (2015). Understanding EFL students’ participation in group peer feedback of L2 writing: A case study from an activity theory perspective. Language Teaching Research 19, 572–593.

Zhao, H. (2010). Investigating learners’ use and understanding of peer and teacher feedback on writing: A comparative study in a Chinese English writing classroom. Assessing Writing 15, 3–17.

Zhao, H. (2014). Investigating teacher-supported peer assessment for EFL writing. ELT Journal 68 (2), 155–168.

Zhu, W. & D. Mitchell (2012). Participation in peer response as activity: An examination of peer response stances from an activity theory perspective. TESOL Quarterly 46 (2), 362–386.

About the Author

Farhad Jafari Basmenj is a graduate student of TESOL at the University of British Columbia, with over ten years of worldwide experience in the field. His areas of interest are genre-based writing, peer feedback, digital literacy, vocabulary learning, and computational assessment of vocabulary.

Modern Journal of Studies in English Language Teaching and Literature Vol. 2 Issue 1. April 2020

10

Differences in Teaching Styles and Oral Language Proficiency of Non-

native English Speaker Teachers: As Perceived by the Iranian EFL

Students

Mohammad Javadi Yasouj University, Iran

Abstract

Non-native English speaker teachers’ (NNESTs) dominant teaching styles and oral language proficiency have recently garnered considerable attention of researchers during the past several years. To determine whether they have been effective teachers from their students’ perspectives, this study intended to scrutinize the possible differences of Iranian senior BA and MA students’ perceptions of their non-native ESTs’ dominant styles of teaching together with oral language proficiency in between and across the universities on the whole. To this end, 103 senior EFL senior BA and MA students participated in the study by the use of multistage cluster sampling procedure from three universities of Isfahan, Shiraz, and Yasouj. For the purpose of data collection, one teaching style questionnaire (TSQ) and one analytic scale for assessing the oral proficiency (ASAOP) were utilized. Through inferential statistics, the results showed that no significant differences for teaching styles and oral proficiency were seen between BA and MA students perhaps due to being exposed to the same university teachers, educational environments, and inter- and intra-communications. Further, the students perceived the dominant teaching styles of their teachers across the three universities quite differently significant, for which history of universities, experience, educational facilities, educational environments, academic ranks of professors, research productivity, and teachers’ marking criteria were influentially involved. Subsequently, as regards the students’ perceptions of their NNESTs’ oral language proficiency, no crucial differences were reflected to occur among the three universities. Presumably, apart from their accent and pronunciation, NNESTs’ interestingness, over-preparedness, qualification, and professionalism have considerably affected their students’ perceptions. Through this study, one can reap benefits from the pedagogical implications of the attained results within the academic settings of the Iran country. Keywords: dominant teaching styles; oral language proficiency; NNES Teachers; students’ perceptions, Iranian universities

Introduction

Considering English as the unsurpassed world language as well as its substantial part as in a juggernaut sounds to be quite commonplace enough to discuss among all language students and teachers throughout the world. Fishman’s claim, “the sun never sets on the English language” (1982, p.18), sheds a great deal of light on the assumption that although English is no longer a guarantee of remaining eternal hegemony due to the emergence of many a common language across the world, it is believed that the language of English is bound to continue to rule almost all the countries for many more periods. Therefore, English use has become indispensible in one’s life and thus having a proficient basis of the English language is now

Modern Journal of Studies in English Language Teaching and Literature Vol. 2 Issue 1. April 2020

11

unavoidable for everybody. This is why, a large number of people, especially in Iran, have gradually been attempting to learn English with an estimated one and a half billion English language apprentices as from 2015 (Gamlo & Noack, 2015). In addition, this difficult enterprise is claimed to be in need of good and skillful English teachers, two important characteristics of whom could be their oral language proficiency and dominant teaching styles.

Needless to say, teaching is deemed one of the most fundamental elements in educational planning which is a crucial factor in conducting educational plans (Bidabadi et al., 2016). In line, “teaching English as a foreign language (TEFL), in expanding circle, is of vital importance” (Noughabi, 2017, p.217). Based on some empirical research projects, effective teaching qualities bring about students’ cognitive outcomes (Muijs, Campbell, Kyriakides, & Robinson, 2005) and to some extent recognize students’ achievement (Darling-Hammond, 2000; Kaplan & Owings, 2002; Goldhaber & Anthony, 2003). Dewar (2002) characterizes a good teacher by what students actually learn in the educational environment through the rundown of organizational objectives and goals. In addition, it is recommended that an English teacher be orally proficient in the language and have some specific teaching styles, contributing to students’ success in learning English. One of the most significant issues of teaching English in an EFL context is the matter of NNE speaker teachers (NNESTs) as being exceeded 80 per cent of the whole English teachers in comparison with NE speaker teachers (NESTs) throughout the world (Canagarajah, 1999).

For well over several decades N and NN English speaking teachers were deemed two

crucially discrepant categories. Albeit the controversial dispute of native ESTs and N-native ES teachers distinction as a hot topic in the world of academia, there are few studies conducted (e.g. Medgyes, 1994) in this area of investigation, reflecting the analyses of differences of these two categories. After all, it is believed that NNESTs are superior to NESTs due to some reasons; for example they are capable of sharing their mother tongue where and when needed for clarity, they can solve their students’ problems more easily with a sense of empathy, and their cultural and educational backgrounds could be of relevance to those of their students which lends itself well to a better path of learning (Llurda, 2005). Thus, students have certain perceptions of their teachers that have to be duty-bound to be looked attentively at for the betterment of their teachers' teaching styles as well as oral language proficiency. The currently startling piece of study has been set out to elicit the Iranian EFL students’ opinions of their N-native ES Teachers’ dominant styles of teaching as well as proficiency of oral language, and determining whether or not senior undergraduate students' perceptions of their NNESTs differ from those of their senior postgraduate counterparts holistically across the three Iranian universities of Shiraz, Isfahan, and Yasouj.

Literature Review

Despite the research projects carried out in such areas as the NNES teachers’ self-perceptions along with NNES teacher’ perceptions of their learners, less attention has been paid to learners’ perceptions of their NNES teachers, especially NNESTs, who come from discrepant language backgrounds (Lasagabaster & Sierra, 2002; Mahboob, 2003; Moussu, 2006). For that matter, Moussu (2002) conducted a quantitative study on four NNESTs from Switzerland, Ecuador, Argentina, and Japan and eighty four ESL students by administering two sets of questionnaires. The findings revealed the positive perceptions of the students towards their NNESTs at the commencement of the academic year. Additionally, teachers gained immense satisfaction from 68% of the students like NSTs, 79% showed respect and admiration for their NNESTs, and lastly 84% of the participants paid attention to the positive aspects of having such a teacher as

Modern Journal of Studies in English Language Teaching and Literature Vol. 2 Issue 1. April 2020

12

a new experience. Nevertheless, Chinese and Korean students expressed dissatisfaction and discontentment with their NNES teachers, holding negative perceptions.

In the same way, Liang (2002) undertook an investigation on twenty ESL students’ standpoints of their six ESL non-NESTs’ accents and speech features with different language backgrounds. Listening to brief audio accounts of teachers tape-recorded before, the students were exposed to a scale of preferences through which they were able to express their opinions regarding their accents and speech features. The results implied that the students reflected positive perceptions of their NNESTs with no attention to their pronunciation and/or accents. Moreover, some experimental studies done in this realm of investigation have led to the conclusion that students hold idiosyncratic perceptions of their NNESTs regarding the same classroom events (Huang, 2006; Block, 1996; Breen, 1991). In a comprehensive study, Mahboob (2003) took both NES and NNES teachers into account which was followed by some yin and yang feedback on the students’ behalf. To put it more cogently, on one hand, NESTs received positive comments regarding their use of vocabulary, oral skills and culture; however, the negative comments reflected their methodology and grammatical structures. On the other hand, NNESTs’ positive comments were concerned with oral and literary skills, grammatical structures, vocabulary, culture, industriousness and question-answering ability; nevertheless, the negative comments yielded evidence for oral skills and culture of the NNESTs.

Barratt and Kontra (2000), in the same vein, considered two groups of learners’

perspectives of their instructors both in China and Hungary, asking them to write down about their experiences freely. Generally, NNESTs were given positive comments in the light of language authenticity, humorous and flexible personalities, the utilization of newfangled methodologies, error correction, and culture knowledge. Nevertheless, NESTs were written about such negative comments as poor teaching styles, culture knowledge, educational values, lack of pedagogical and professional organization and preparation, low understanding of students’ learning difficulties together with different English accents problems.

Taking everything into consideration, the present study addressed the research

questions and hypotheses as follows: 1) Do senior BA students' perceptions of their NNESTs' teaching styles differ from those of

their senior MA counterparts significantly? 2) Do senior BA students' perceptions of their NNESTs' oral proficiency differ from those of

their senior MA counterparts significantly? 3) Do the Iranian senior EFL students' perceptions of their NNESTs' teaching styles vary

among the three universities? 4) Do the Iranian senior EFL students' perceptions of their NNESTs' oral proficiency vary

among the three universities?

As regards the nature of quantitative method design and the above-mentioned research questions, the null hypotheses were constructed as jotted down:

Null Hypothesis 1: No difference exists between the senior BA students' perceptions of their NNESTs' teaching styles and those of their senior MA counterparts significantly. Null Hypothesis 2: No difference exists between the senior BA students' perceptions of their NNESTs' oral proficiency and those of their senior MA counterparts significantly. Null Hypothesis 3: No differences exist between the Iranian senior EFL students' perceptions of their NNESTs' teaching styles among the three universities significantly.

Modern Journal of Studies in English Language Teaching and Literature Vol. 2 Issue 1. April 2020

13

Null Hypothesis 4: No differences exist between the Iranian senior EFL students' perceptions of their NNESTs' teaching styles among the three universities significantly.

Methods In order to examine and detect the underlying elements present in participants’ perceptions of their NNESTs, this research adopts a quantitative method approach combining an analytic scale of oral language proficiency and a teaching styles questionnaire. Besides, on the word of Cohen et al. (2007), whenever different participants are investigated at a single point of time, the study refers to a “cross-sectional” one. Thus, the cornerstone of this study has been laid on a descriptive cross-sectional survey method.

Participants

Through multistage cluster sampling, a total of 103 EFL senior BA (75.7%) and MA (24.3%) students from Isfahan, Shiraz and Yasouj universities of Iran were selected to take part in the survey due to their easiness of accessibility. All participants (65 females [63.1%] and 38 males [36.9%]) were majoring in TEFL whereas they failed to be of the same level of education, English study years (from 5 to at least 13 years), age (from 22 to 32), university (Isfahan [32.0%], Shiraz [36.9%], and Yasouj [31.1%]), and, gender. The reason behind choosing senior students as the participants was their long-term familiarity with their NNES teachers’ seminal issues as in dominant teaching styles and oral language proficiency.

Instruments Teaching Style Questionnaire (TSQ)

To achieve the study objectives, use was made of a Teaching Style Questionnaire (TSQ) developed by Benke and Medgyes’s (1994) with the purpose of eliciting students’ perspectives of their N-native E speaker Ts’ dominant teaching styles. The five-point Likert-type questionnaire comprised 23 items and 2 components. The former component refers to classroom management issues (13 items) and the latter one is concerned with the personal characteristics (10 items). Then, TSQ was first observed by two TEFL PhD holders for the establishment of face and content validity. After they confirmed its validities, TSQ was randomly piloted with 40 senior university TEFL students from Yasouj University similar to the study participants for the purpose of reliability. To this end, TSQ attained the desired reliability level with Cronbach's alpha quantified at the point of 0.88 for 23 items. Furthermore, for the sake of construct validity, an attempt was made to run confirmatory factor analysis to show factors numbers as being measured along with the relationships which exist between the factors. Before that, Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett's Sphericity Test was required for determining data acceptability and appropriateness to determine whether the items are factorable enough in order to run the factor analysis. (See Table 1)

Modern Journal of Studies in English Language Teaching and Literature Vol. 2 Issue 1. April 2020

14

Table 1

KMO and Bartlett's Test for TSQ

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy 0.615 Bartlett's Test of Sphericity Approx. Chi-Square 458.256

Df 521 Sig. 0.000

According to Field (2000), if the value of KMO is 0.5 or more, then the data driven from the sample will be highly likely to become factorable. Table 1 shows the value of sampling adequacy KMO measure is 0.61, being greater than 0.5 value as suggested by Field (2000). As mentioned above, the KMO value revealed that factor analysis could admittedly be run on the pilot sample. Additionally, as can be seen in Table 1, the Bartlett's Sphericity Test (Bartlett, 1954) was statistically reported to be meaningful with the level of confidence more than 99% (p<0.001), designating a significant correlation between the variables. Additionally, Table 2 serves as the illustration for descriptive statistics of the whole items of the questionnaire which were determined mathematically.

Table 2

Descriptive Statistics

Item Mean SD Item Mean SD Q1 4.12 1.042 Q13 4.10 1.081 Q2 3.72 1.339 Q14 3.05 1.449 Q3 4.12 1.113 Q15 2.12 1.399 Q4 4.45 0.904 Q16 3.22 1.476 Q5 4.05 1.153 Q17 2.72 1.568 Q6 4.05 1.084 Q18 3.02 1.510 Q7 3.35 1.387 Q19 3.12 1.453 Q8 3.25 1.171 Q20 3.10 1.428 Q9 3.95 1.153 Q21 3.55 1.338 Q10 3.92 1.248 Q22 3.12 1.435 Q11 4.12 1.136 Q23 3.02 1.510 Q12 4.30 0.882

As shown in Table 2, the highest mean (M4=4.45) refers to Item 4 which is concerned with a lot of homework assigned to the students by NNESTs that is relevant to the classroom management component. On the other hand, the lowest mean (M15=2.12) belongs to Item 15 dealing with personal, albeit teaching-related characteristics of NNESTs, i.e., personal characteristics component. Therefore, it is worth mentioning that Item 4 seems to be greatly significant in the TS questionnaire. Moreover, Table 3 clarifies eigenvalues and total variance explained for each factor retained in the final analysis of factor.

Modern Journal of Studies in English Language Teaching and Literature Vol. 2 Issue 1. April 2020

15

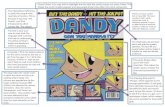

Through Principal Component Analysis (PCA), the number of components was verified. In fact, PCA is a statistical technique to share various resemblances to confirmatory factor analysis and to determine whether different groups of items are set together for making a distinct component (Brown, 1996; Gorsuch, 1990; Stevens, 2009; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013; Wintergerst, DeCapua, & Itzen, 2001). Accordingly, the three criteria, i.e., Kaiser's rule of keeping components together with eigenvalues higher than 1, the scree plot of eigenvalues, and the component solution of the items, as suggested by Tabachnick and Fidell (2007), were considered to specify the component numbers to rotate. To this end, based on Table 3, use was made of an opening examination so as to measure eigenvalues meant for every single component throughout the whole data. Besides, rotation sums of squared loadings revealed that the two components were provided with eigenvalues higher than 1, indicating 68.84 % of the total variance in the participants' responses. In line with the method used, none of the components were detached from the questionnaire. Also, scree plot was defined as one of the procedures used in establishing the factors numbers so as to be maintained in the analysis of factoriality (Cattell, 1966). Thus, the factors’ numbers equal the points’ numbers above the break (See Figure 1).

Figure 1. Scree Plot of the Components The plot of scree demonstrates two big drops above one, which purports to be the

number of components for keeping the rotation to an interpretable solution to be constructed as depicted by Figure 1. The eigenvalues with a value more than 1 refer to the first two components. Between component two and three, there appears to be a big drop in eigenvalue as shown in the figure above. At the cliff base on the scree plot, there does appear component 1 and 2, below which component 3 up until 23 stands out as the scree.

The two determined components of 1 and 2 represent 69% of the total proportion of variance. Therefore, the first two components were selected to be kept. The following rotated

Table 3

Total Variance Explained

Components

Initial Eigenvalues Rotation Sums of Squared Loadings

Total % of Variance

Cumulative % Total % of

Variance Cumulative %

1 9.897 43.032 43.032 8.424 36.628 36.628 2 5.936 25.809 68.841 7.409 32.214 68.841

Modern Journal of Studies in English Language Teaching and Literature Vol. 2 Issue 1. April 2020

16

component matrix table of confirmatory factor analysis pertained to the TSQ illustrates loading of items on each factor below.

Table 4

Factor Analysis of TSQ and Loadings of Each Item on Each Factor

Rotated Component Matrix Factor Factor 1 2

Q 6 0.841 Q 2 0.839 Q 9 0.837 Q 1 0.810 Q 3 0.778 Q 10 0.767 0.354 Q 5 0.751 0.411 Q 4 0.736 Q 13 0.654 Q 12 0.642 Q 11 0.638 Q 8 0.612 Q 7 0.600 Q 22 0.970 Q 18 0.954 Q 23 0.954 Q 14 0.946 Q 20 0.945 Q 16 0.911 Q 19 0.911 Q 21 0.287 0.767 Q 17 0.747 Q 15 0.345 0.617

As is evident from Table 4, each factor loading is illustrated after rotation. According to Kinnear and Gray (1994), the aim of rotating data is to make the data structure simple and understandable. When an actual value of loading is equal or greater than 0.30, that item is loaded on the component (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). Thus, an attempt was made to adjust the same criterion in order to opt for the item loadings on each component. By the same token, no item was deleted as all item loadings were higher than 0.30. Table 4 shows four items were loaded on more than one component, so use was made of choosing the most fitting item according to a criterion established by Rezvani (2010) who maintained that once the difference between cross loaded items is determined as a point higher than 0.15, one must choose the greater item loading in that case. In Table 4, it is clear that thirteen items were loaded and listed under the first component (i.e., items of 6, 2, 9, 1, 3, 10, 5, 4, 13, 12, 11, 8, and 7). As items 5 and 10 were loaded on the two components, Rezvani (2010) suggested that one should take the greatest loading value into account. As such, considering the considerable differences between the loading values on the two components for items 5 and 10, the higher loading values, namely, 0.411 and 0.354 respectively, being under the first component, were taken as the real loading values. For that matter, while items 5 and 10 were listed under the first and second components at the same time and because their difference was greater than 0.15, they were

Modern Journal of Studies in English Language Teaching and Literature Vol. 2 Issue 1. April 2020

17

retained under the first component in which they were loaded more strongly. Therefore, all the above-mentioned items were loaded only under one component, namely, component one whose item loading values were higher than 0.30. As a result, there was no item deletion in this component. On the other hand, one can see that the rest of items, i.e., 22, 18, 23, 14, 20, 16, 19, 21, 17, and 15 were loaded under the second component. In addition, items 21 and 15 which should be merely loaded under the second component are listed under component one as well. It is worthy of note that their loading values, i.e., 0.767 and 0.617, are considered as the highest values under the second component in comparison with the first component, so they were placed under component two. It should be noted that their contents were in line with the second component. Consequently, all items were put in order successively in light of their real loading values on each component and the final draft of the TSQ with 23 items, enjoying an acceptable value of Cronbach's alpha reliability (0.88) was established.

Analytic Scale for Assessing Oral Proficiency (ASAOP)

The Analytic Scale for Assessing Oral Proficiency (ASAOP) was employed to elicit the students' perceptions of their NNESTs' level of oral language proficiency (www.nclrc.org, 2015). This four-point Likert-type scale fell into four components of ‘pronunciation’, ‘fluency’, ‘grammar/language use’, and "vocabulary". As for its face and content validity, ASAOP was given to two TEFL PhD holders. When face and content validities of the ASAOP were confirmed, an attempt was made to re-validate it since being used in a new context. Therefore, the ASAOP was piloted with a sample of 15 subjects from Yasouj University with comparable features of the main participants, after which the test-retest reliability method was applied with a three week interval.

Table 5

Test–retest Reliability for ASAOP 1 and ASAOP 2

A 3-week interval Pearson Correlation SD Mean N Sig.

ASAOP 1 (test) .704** 0.33 2.96 15 0.003

ASAOP 2 (retest) .704** 0.29 3.10 15 0.003

Note: ** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). As depicted by the fifth table, correlation of test-retest was significant at the alpha value

of 0.003, hence a positive relationship flanked by the two sets of scores obtained from ASAOP 1 and ASAOP 2 at a three week interval among the respondents (r=.704, p<0.01) with an acceptable reliability coefficient.

Data Collection Procedure and Analysis

In order to gather the required date, the instruments were administered to the participants. The TSQ and ASAOP were in English and were sent to the students through Whatsapp, Email, Telegram, LinkedIn, and some were handed in directly. They were given enough time with full explanation of how to fill in the questionnaires. It must be mentioned that before administering the questionnaires to the participants, the researcher had already

Modern Journal of Studies in English Language Teaching and Literature Vol. 2 Issue 1. April 2020

18

obtained their permission for ethical issues of research. All in all, one hundred and twelve students responded to the questionnaires accurately, nine of whom were excluded from the total number of the questionnaires in the aftermath of missing data. As a result, both inferential and descriptive statistics were applied to analyze the collected data by SPPS.

Results

As regards the initial research question on comparing means of the two groups, independent sample t-test was employed to analyze means of the two groups, i.e., the senior B.A. and M.A. students. In this connection, standard deviation, number of participants, and means of the groups were precisely gaged in the following table.

Table 6

Groups' Statistics

Level of Education N Mean Std.

Deviation Std. Error

Mean Teaching

Style B.A. 78 85.74 14.729 1.667 M.A. 25 78.56 20.910 4.182

As it is obvious in Table 6, 78 senior B.A. students and 25 senior M.A. students of the three universities participated in the present study. Accordingly, B.A. students' mean (85.74) was reported to be by far discrepant from the M.A. students’ mean (78.56). By the same token, standard deviation in B.A. group was 14.729 and the standard deviation of M.A. group was estimated to be 20.91 by the use of SPSS. The following table presents the independent sample t-test results.

Table 7

The Result of Independent Samples t-test

Levene's Test for

Equality of Variances

t-test for Equality of Means

F Sig. t df Sig. (2-tailed)

Teaching Styles

Equal variances assumed 2.859 .094 1.905 101 .060 Equal variances not

assumed 1.596 31.988 .120

Table 7 exhibits the non-existence of any difference concerning all B.A. and M.A. students' perceptions of their NNES teachers at the universities in the light of teaching styles in a significant manner. Not to put too fine a point on it, since the significant level of alpha is more than 0.05; therefore, no statistically significant difference (t=1.905, df=101, sig.2-tailed p>0.05) was found to exist between the two groups (sig=0.060). In the same way, the first null hypothesis was confirmed underpinning the first research question.

Modern Journal of Studies in English Language Teaching and Literature Vol. 2 Issue 1. April 2020

19

In like manner, the subsequent question was correspondingly motivated to ascertain the presence of a significant difference concerning all B.A. and M.A. students' perceptions of their NNES teachers' level of oral language proficiency. Consequently, independent sample t-test, mean, and also standard deviation were computed for that matter. (See Table 8)

Table 8

Groups' Statistics

Level of Education N Mean Std.

Deviation Std. Error

Mean

Oral Proficiency

B.A. 78 2.84 0.477 0.054 M.A. 25 2.83 0.524 0.104

The figures in Table 8 indicate that 103 students participated in this research project, 78 of whom were B.A. and the rest were M.A. students of Shiraz, Isfahan, and Yasouj universities. Mean score of the first group was estimated to be 2.83 with standard deviation of 0.477 and mean score of the second group was 2.84 with 0.524 level of standard deviation. In parallel with the procedure used for the previous question, independent sample t-test was utilized and relevant findings were achieved as follows:

Table 9

The Result of Independent Samples t-test

Levene's Test for

Equality of Variances

t-test for Equality of Means

F Sig. t df Sig.

Oral Proficiency

Equal variances assumed 1.170 .282 .030 101 .976 Equal variances not

assumed .028 37.666 .978

Generally speaking, based upon Table 9 above, no meaningful discrepancy was discovered between all B.A. and M.A. learners' perceptions of their university NNES teachers in the light of oral language proficiency. This is owing to the fact that the significant level of alpha was calculated more than 0.05 (p>0.05, t=0.030, df=101, sig=0.976) understandably. Let these above figures suffice to reveal that underpinning research question number 2, the second null hypothesis was supported.

Considering the third question which combed for discerning meaningful differences among the Iranian senior EFL learners' perceptions of their NNESTs' dominant teaching styles across the three universities of Shiraz, Isfahan, and Yasouj, use was made of One Way ANOVA. Furthermore, a posthoc Tukey Test was also performed for additional scrutiny so as

Modern Journal of Studies in English Language Teaching and Literature Vol. 2 Issue 1. April 2020

20

to compare and imply results gained from the three groups of universities. In so doing, Table 10 initially displays the descriptive statistics chosen from each university separately.

Table 10

Descriptive Statistics of ANOVA for TS

Universities N Mean Std. Deviation Std. Error

Shiraz 38 86.52 11.924 1.934 Isfahan 33 87.72 11.096 1.931 Yasouj 32 77.15 23.261 4.112 Total 103 84.00 16.620 1.637

As Table 10 denotes, a small difference was identified across the three groups. All senior B.A. and M.A. students of Shiraz University were 38 alongside the standard deviation of 11.924 as well as the mean score of 86.52. Moreover, 33 students were from Isfahan University accompanied by the mean score of 87.72 in addition to standard deviation of 11.096. And finally, 32 students were from Yasouj University with the mean score of 77.15 and a value of 23.261 for standard deviation. On balance, 103 students possessing the mean score of 84 plus the deviation of standard equal to 16.620 responded to the TSQ. The following table demonstrates the analysis of variances across the three groups.

Table 11

One-Way ANOVA Results for Students' Perceptions of their NNESTs' Teaching Styles across the Three Universities

Teaching Styles Sum of Squares df Mean Square F Sig.

Between Groups 2199.762 2 1099.881 4.234 .017 Within Groups 25976.238 100 259.762

Total 28176 102

As evident in Table 11, the F-observed value is 4.234. Furthermore, the acquired alpha value was appraised lesser than 0.05 (F (2, 100) = 4.234, (p=0.017)). That being the case, because the level of alpha value is meaningful at the point of 0.017 (p<0.05), groups were statistically different in terms of their perceptions of their NNESTs' all-embracing teaching styles. Moreover, a Tukey HSD test was additionally utilized as encapsulated in Table 12.

Modern Journal of Studies in English Language Teaching and Literature Vol. 2 Issue 1. April 2020

21

Table 12

Multiple Comparisons (Tukey HSD)

(I) University

(J) University

Mean Difference (I-J) Std. Error Sig.

Tukey HSD

Shiraz Isfahan -1.200 3.835 .947 Yasouj 9.370* 3.866 .045

Isfahan Shiraz 1.200 3.835 .947 Yasouj 10.571* 3.998 .026

Yasouj Shiraz -9.370* 3.866 .045 Isfahan -10.571* 3.998 .026

*. The mean difference is significant at the 0.05 level. As displayed in Table 12, a slightly significant difference was found between Shiraz

and Yasouj university language learners' viewpoints on their N-native E speaking T’s styles of teaching with the significant value of 0.045 at the level of (p<0.05). In addition, the students of Isfahan and Yasouj universities were also different in terms of their perceptions with the statistically significant value of 0.026 at the level of (p<0.05). Albeit the above-mentioned computations, no meaningful discrepancy was observed among the Isfahan along with Shiraz University students' perceptions (sig=0.947, p>0.05). Furthermore, underpinning question three, the third null hypothesis was refuted as the students of at least two universities did show differences when their perceptions were compared. As such, a graphic plot of means related to the mean differences across the three universities is illustrated below. (See Figure 2)

Figure 2. Means Plots of Three Groups on the Teaching Style Variable

As shown in Figure 2, the mean scores of Shiraz and Isfahan Universities were approximately close to each other (86.52 and 87.72 respectively) whereas one can spot a noticeable gap between the Yasouj University mean score (77.15) and the two other universities.

Similarly, the fourth question sought to investigate the differences between all B.A. and M.A. students' perceptions of their NNES teachers' level of oral language proficiency across the three universities. Thus use was made of One Way ANOVA once again so as to compare the three intended categories in terms of mean marks. Descriptive statistics are shown below (See Table 13).

Modern Journal of Studies in English Language Teaching and Literature Vol. 2 Issue 1. April 2020

22

Table 13

Descriptive Statistics of ANOVA for Oral Proficiency

Universities N Mean Std. Deviation Std. Error

Shiraz 38 2.71 0.469 0.076 Isfahan 33 2.93 0.463 0.807 Yasouj 32 2.85 0.515 0.0911 Total 103 2.83 0.486 0.047

As illustrated in Table 13, the mean score of the senior B.A. and M.A. students of Shiraz University was 2.71 along with deviation of standard as being 0.469 and mean of 2.93 with standard deviation of 0.463 belonged to Isfahan university students. Finally, Yasouj University received a mean score of 2.85 as well as a gained value of 0.515 for deviation of standard. The findings underlying One Way ANOVA F-test are posed in the following chart.

Table 14

One-Way ANOVA Results for Students' Perceptions of their NNESTs' Oral Proficiency across the three Universities

Oral Proficiency Sum of Squares df Mean

Square F Sig.

Between Groups .906 2 .453

1.947 .148 Within Groups 23.267 100 .233 Total 24.174 102

As indicated in table 14, the F value (F (2, 100=1.947)) failed to reach the statistical significance (Sig. =0.148). As the alpha value failed to statistically be meaningful (p>0.05); therefore, no meaningful relationship existed across the three groups of universities. In addition, the fourth null hypothesis was confirmed in the aftermath of detecting not any gap among the three categories.

Discussion

As regards the findings of the first research question, no meaningful gap was pinpointed in a statistical manner as related to two groups of senior BA and MA learners’ perspectives of their N native ES Teachers’ styles of teaching. Perhaps this lies in the assumption that both groups were enjoying the same university teachers, educational environments, and inter- and intra-communications among themselves. Thus, they, to a great extent, shared similar perceptions of their teachers with regard to the styles of teaching. Likewise, this could be justified by a similar study conducted by Zhang and Liu (2007) who explored the students’ preferences for their NNESTs owing to the numerous strategies they opt for teaching which were favorable to their tastes. Other studies purport to be in harmony with the results of this study in a sense that the presence of NNESTs at academic environments was deemed to be an indispensable issue because of apportioning similar cultural milieu together with undifferentiated first language as a result of which their teaching styles could be more helpful, intelligible, and effective, as

Modern Journal of Studies in English Language Teaching and Literature Vol. 2 Issue 1. April 2020

23

perceived by the students (Lasagabaster & Sierra, 2002; Madrid, 2004; Torres, 2004; Mahboob, 2003; Moussu, 2006).

In like manner, the second research question was presented to investigate whether or not there is any statistically significant difference between all B.A. in addition to M.A. learners' attitudes toward their N native ESTs' level of oral proficiency. For that matter, t-test for independent samples got employed for the purpose of verifying the possible dissimilarity. In consequence, no substantial gap was reported to exist among two aforesaid groups on the basis of the statistical figures. Possible reasons for this gap could be congruent with the probable justifications for the previous research question in that B.A and M.A students have the same teachers, educational environments, and intra- and inter-personal communications throughout the universities. Another probable reason for the similarity of perceptions could be due to the cultural bias in which overlooking the cultural differences and preferring one’s culture to the other would occur, affecting minorities on diverse levels of education (Bondy & Peguero, 2011; de Jong & Harper, 2008).

So it is recommended that one take culturally-appropriate environments and possible bias into consideration while deciding on and opting for assessments and deciphering the achieved results. The result obtained by this research question is in line with other studies with different foci, showing no significant difference and connection flanked by learners’ assessing of their professors besides the level of education in that it makes no significant difference whether they are undergraduates or postgraduates (Thomas & Aleamoni, 1980; Rothermel & Divoky, 1988).

The third research question was motivated to delve into the gaps as to students' viewpoints on their non-N English STs' dominant teaching styles across the three universities by means of One Way ANOVA. In this connection, Tukey's Test was also run and significant differences emerged between all three groups in such a way that Isfahan and Shiraz university language learners' attitudes towards their teachers' styles of teaching failed to statistically different; however, Yasouj counterparts’ differed from them significantly. One of the main reasons for this could lie in the assumption that Shiraz and Isfahan Universities were founded in the fourth and fifth decades of the 21th century in that they have a long history in terms of experience, educational facilities, educational environments, and scientific atmospheres. However, Yasouj University has been established since two recent decades; therefore, it enjoys different educational methods accompanied by different teachers with diverse teaching styles, backgrounds and the like. Perhaps it is a critical issue influencing the students' attitudes in this regard. To put it better, the source of this difference could be found in the ranks of NNESTs at the universities which affected learners’ attitudes in that teachers of higher academic rank receive higher student ratings of their teaching styles (Walker, 1969; Gage, 1961). Curious as it may seem, Shiraz and Isfahan university teachers with an enriched background of knowledge and higher academic ranks might have affected their students’ positive perceptions of their teaching styles agreeably rather than those of Yasouj university teachers with lower academic ranks disagreeably.

To put it into perspective, in a study conducted by Aleamoni (1981), students perceived their teachers positively in that they were considered friendly, warm, and humorous in the classroom context; however, once their course objectives along with their stimulation methods exigencies failed to be met properly, teachers were to blame and criticized frankly on the behalf of the students. Last but certainly not least, one of the most probable reasons for the addressed gap could be likely because of the positive correlation between the participants’ ratings of their NNESTs and their true or expected score they gain in a course of instruction from their instructors. Basically, students are usually satisfied with a teacher, from whom they receive good marks (Callahan & Goldberg, 1991; Wilson, 1998; Rodabaugh & Kravitz, 1994). In line with literature, perhaps Yasouj students perceived their NNESTs quite strict about scoring that

Modern Journal of Studies in English Language Teaching and Literature Vol. 2 Issue 1. April 2020

24

is mentioned in the TSQ as well (Item 21: My teachers are too harsh in marking), reflecting their dissatisfaction at any rate (Barratt and Kontra, 2000).

The last research question was motivated to determine the differences between students' perceptions of the three universities toward their NNES teachers' level of oral language proficiency. Using One Way ANOVA, the results were indicative of existing no significant differences among them. Probably, the most salient justification behind the lack of a significant difference in this regard is that the professors in current study are all non-NE speakers; therefore, they share their non-nativeness while pronouncing words, producing lexical phrases and meaningful sentences using a good command of grammatical structures with an effortless, smooth and speedy speech. Although, there may exist some identifiable deviations in NNESTs’ pronunciation with a range of limited phonemic errors, their accents which are in a way marked with occasional mispronunciations fail to necessarily impede understanding.

In agreement with the literature, this finding corroborates the ideas of Liang (2002), who suggested that in spite of the students’ ratings of their ESL teachers’ pronunciation and accent in their speech significantly, such elements failed to have some bearing on the perceptions of the students respecting their former N-native E Speaking Ts in their home countries. Generally, they reflected positive perceptions of their teachers because such personal factors as interestingness, overpreparedness, qualification, and professionalism affected their attitudes more preferably than their accent and pronunciation which were somewhat considered two extraneous features from an initial impression. As stated in the literature, Mahboob (2003) also pinpointed the issue by referring to the NNS teachers’ oral skills as being mostly perceived positively by the participants or perhaps not as important as other elements to be considered.

Conclusion

In summation, the existent study was conducted for determining whether or not Iranian EFL senior undergraduate students’ perspectives of their Non-N English STs’ styles of teaching plus proficiency of oral language are different from those of their senior postgraduate counterparts on the whole and among the three Iranian universities of Shiraz, Isfahan, and Yasouj. In so doing, a teaching style questionnaire (TSQ) developed by Benke and Medgyes (1994) was adopted comprising two major components. Granted that the questionnaire was to be used in a new context, the validation process was an indispensable prerequisite. Thus for the pilot study, it was administered to 40 TEFL students randomly selected from University of Yasouj with similar characteristics of the main sample of the study. Then two TEFL experts confirmed the questionnaire in terms of its content and face validities. To examine its construct validity, use was made of confirmatory factor analysis. After the process of factorial analysis, 13 items were loaded under the initial component and the rest under the subsequent one. Finally, respecting the questionnaire reliability, Cronbach's alpha was calculated through SPSS (0.88) without any item deletion.

An analytic scale for assessing oral proficiency (ASAOP) taken from the George Washington University Website (www.nclrc.org, 2015) was also utilized to measure the NNESTs' level of oral language proficiency. Its face and content validity were established by two experts. It included four items of fluency, grammar, vocabulary, and pronunciation. As for its reliability, use was made of test-retest reliability with a three-week interval. The correlation statistics showed a positive relationship (p<0.05) in a meaningful manner between the two sets of scores (r=0.704, sig=0.003), representing the reliability of ASAOP. The participants were chosen through multistage cluster sampling strategy from three universities of Shiraz, Isfahan, and Yasouj. Then as regards the first and second research questions for determining the possible differences between two groups of B.A. and M.A. students' attitudes towards their Non-N English STs' dominant styles of teaching over and above oral language proficiency, t-tests for independent samples were proceeded. According to the findings, no statistically

Modern Journal of Studies in English Language Teaching and Literature Vol. 2 Issue 1. April 2020

25

meaningful difference for teaching style was seen. On the other hand, as regards the possible difference between perceptions of B.A. and M.A. students' towards their teachers' level of oral proficiency, again, no statistically significant difference was reported to exist. Perhaps that was because of being exposed to the same university teachers, educational environments, and inter- and intra-communications. Moreover, the third research question was designed to measure the possible gaps among the students' perspectives of their teachers' dominant teaching styles across the three universities. For that matter, ANOVA test was utilized in that the alpha-value was smaller than 0.05, hence significant. Then in order to show the differences among the three groups of universities, Tukey's Test was run and the findings disclosed differences among Yasouj university and the other two universities significantly; however, no significant difference was found between Shiraz and Isfahan universities. Possible reasons for this could have been due to history of universities, experience, educational facilities, educational environments, academic ranks of professors, research productivity, and teachers’ grading or marking which affected their students’ ratings. Finally, the last research question sought to ascertain the gaps, if any, of the learners’ perceptions of their NNESTs’ level of oral language proficiency among the three universities, for which no significant differences were found. Possibly, NNESTs’ interestingness, overpreparedness, qualification, and professionalism influenced their perceptions other than their accent and pronunciation.

In the end, N-Native English STs can make the most of the study findings to better apply diverse and helpful teaching styles, to fill in the gaps they think they fail to have, to obtain considerable insights into the use of reflective practices, and finally to improve their language literacy and proficiency in case of any failure. Besides, they can use the results to practice their own teaching styles in the classroom context, enhance awareness of their positive and negative consequences of understanding the effectiveness of their oral proficiency, if at all, and finally have a voice in both EFL and ESL contexts.

References

Aleamoni, L. M. (1981). Student ratings of instruction. In J. Millman (Ed.), Handbook of teacher evaluation (pp.110-145). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Barratt, L., & Kontra, E. (2000). Native English-speaking teachers in cultures other than their own. TESOL Journal, 9(3), 19–23.

Bartlett, M. S. (1954). A note on the multiplying factors for various chi square approximation. Journal of Royal Statistical Society, 16(Series B), 296-8.

Benke, E., & Medgyes, P. (1994). Differences in teaching behavior between native and non-native speaker teachers: As seen by the learners. In E. Llurda (Eds.), Non-native language teachers: Perceptions, challenges and contributions to the profession (pp. 195-215). New York: Springer.

Bidabadi, N. S., Isfahani, A. N., Rouhollahi, A., & Khalili, R. (2016). Effective teaching methods in higher education: requirements and barriers. Effective teaching method in higher education, 4(4), 170-178.