MINKISI FIGURES -...

-

Upload

doankhuong -

Category

Documents

-

view

219 -

download

1

Transcript of MINKISI FIGURES -...

MINKISI FIGURES

OF THE CONGO

CHRISTOPHER MP CHUHNA

Theory and Method Material Culture Study

Dr. McCleary

Spring 2016

Chuhna 1

Introduction

Spiritual power in the Western world had a divide between the good and the bad, the

black and white views of spiritual power. For the KiKongo language of the BaKongo people

there was no word that easily translated into religion, instead they practiced witchcraft and

magic. In BaKongo spiritual power structure there was no definitive separation between good

and bad magic and witchcraft. The spiritual powers were neutral, but the practitioners

manipulated the powers to be good or bad depending on their usage of the power. A

practitioner using their spiritual powers for the good of the community was on the righteous

side of the spectrum, even if their actions were harming another person. A practitioner that

started using their spiritual powers for personal gains that inflicted harm on another person and

not to help the community, whether it was for good intentions or bad intentions, would have

fallen on the bad side of the spectrum. The power came from the land of the dead, and the land

of the dead was a mirror of the living world. For the Kongolese there was not any distinction

between the land of the dead and the land of the living. Rivers and bodies of water were how a

spiritual practitioner could communicate with the land of the dead. The word power in

KiKongo translated to kindoki, and kindoki was the center of the Nganga’s spiritual powers.

Kindoki was important for the chiefs, because if they had a large amount of kindoki they

would be an effective leader and have success at his ventures.

The power that resided in the land of the dead was harness able through the minkisi

(sing. Nkisi) figure of the Congo. The minkisi came in various shapes, sizes, and physical

appearance, and they each varied in the amount of power they contained. The figures were

normally male figures, and in some cases the figures were female. The male figures were

Chuhna 2

stronger and the female figures were less powerful. The figures had human form and were

wooden carvings and in some cases bodies would have a covering. These coverings were to

help strengthen the minkisi and to help aid in their desired tasks. The figures would also get

infused with the three domains of nature come together. Minerals, vegetables, and animal

matter are the three domains of nature, and these items helped strengthen the figure and the

residing spirit’s power. Once the infusing of the three domains of nature was complete they

would get a covering of some kind of resin. Then covered with a mirror, which strengthened

the minkisi access to the spirit world. The figure would then go through a ceremony that

activated it, and after the activation ceremony the figure was ready for its intended task. With

an nkisi ready for use it would enter into the society ready to interact with the community

members. The minkisi had great influence in Congolese world, and they had active roles in the

societies. What was the role of the Minkisi figures in the Congolese world and then how were

they viewed in the Western world during the 20th century?

Historiography Section

Many of the scholar works dealing with the minkisi figures were from an art historian

view and examine them from a stylist view point. Most of the secondary sources about the

minkisi were from non-African writers such as Reverend J.H. Maw, who was a missionary

sometime before 1935. Reverend Maw commissioned different objects from the Congo and

wrote about the objects’ purpose in the society. There were a few primary sources written from

the African voice, one such source was the K.E. Laman manuscripts, written by the BaKongo

people and collected by Laman. There were writings dealing with the creation and uses of the

minkisi figures. American museums have a large collection of minkisi figures in their African

Chuhna 3

history collections, which allow scholarly writers to examine the minkisi in person and through

high resolution photographs.

Much of the scholarly work done dealt with the making and purpose of the minkisi.

Scholars like Zdenka Volavkova, in her article Nkisi Figures of the Lower Congo1, discussed

the several reasons of creating the minkisi figures and how the completed design of the figure

was not always an effect of the artesian. Other than the carving of the figure the artesian did

not have much say in the figure’s appearance. The artesian often would not know the usage of

the nkisi. After the carving of the nkisi the influence of the design was up to the Nganga. The

figure took on different characterizes that the Nganga felt were necessary so that the nkisi

could carry out its intended purpose. Volavkova also discusses the nkisi nkondi, she explains

the activation process of the nkondi figures. Volavkova also examines the morphological

features of the nkondi, which would be the pose and gestures of the figures that have

traditional symbolic meaning. Volavkova ends that article discussing the influences of the

Europeans and how it did affect some of the Kongolese art. Despite the European influences,

the minkisi did not go through any fundamental changes, remaining an African influenced

object.

Explores and missionaries examined the minkisi figures for more than three hundred

years. Westerners collected minkisi figures for hundreds of years, and the collecting was for

both personal and museum collections. Betty Gubert examines minkisi figures in her

article Three Songye and Kongo Figures2, these figures that Gubert examined were from a

collection at the Schomburg Center for research Libraries of the New York Public Library.

1 Zdenka Volavkova, “Nkisi Figures of the Lower Congo”, African Arts 5, 2 (1972): 52-84.

2 Betty Gubert, “Three Songye and Kongo Figures”, African Arts 15, 1 (1981): 46–88.

Chuhna 4

Gubert wrote about some of the differences that the minkisi figures can have, and how there

were different types of minkisi figures. She also observes that the Ngangas needed knowledge

of botany, psychology and theatrical arts, so to endow the figure with the power to give the

desired results. She gives details about the three realms of nature that going into the stomach

hole of the nkisi figure. The first of these elements was clay from a river bed where the sprints

resided. The other elements are herbs and roots (that can either kill or cure) and animal parts

(parts that help the animal survive or communicate strength or power). If the nkisi is not

having the desired effect it means that either the nkisi is in need of a renewal ritual or it could

mean that there is a stronger nkisi that is overpowering it.

Scholars examining the minkisi figures have looked at the stylist and visual aspects of

the figure, but few have examined deeper into their roles in the societies. Wyatt MacGaffey has

peered past the aesthetic of the minkisi figures and examined the purposes of the minkisi in the

Kongolese societies. MacGaffey did not only examine the minkisi figures, he also uses the

K.E. Lamam manuscripts to assist his arguments. In Fetishism revisited: Kongo “nkisi” in

Sociological Perspective3 MacGaffey examined the relationship between the figures, spirits

and practitioners. He used the Lamam manuscripts to understand the sociological perspective

of the minkisi figures on the Kongolese society. MacGaffey discusses the medicines that went

into the stomach area of the nkisi, and he explains how each nkisi had its own medicine recipe.

Making each nkisi figure was for different reasons and practitioners, so the recipes would be

different. MacGaffey discusses that the power of the minkisi came from the spirit world, but

there were living people as well that had considerable amounts of power (kindoki). The living

that had power were the either living elders or chiefs. MacGaffey examines the fundamental

3 Wyatt MacGaffey, “Fetishism revisited: Kongo “nkisi” in Sociological Perspective”, Africa: Journal of the International African Institute 47, 2 (1977): 172-184

Chuhna 5

concepts between the figure and the spirits that inhabit them. The figures were the visible

containers that the spirits could enter into social interactions. In The Personhood of Ritual

Objects: Kongo “Minkisi”4 MacGaffey explains how minkisi figures acquired a sense of

personhood within the communities it resided in. MacGaffey explained that the idea of an

inanimate object having a sense of personhood was not just a Kongolese idea. He drew

parallels to Medieval European relics of the saints, and how these objects took on a living

persona of its own. MacGaffey uses the beginning of his work to explain what the nkondi’s

roles and purposes. He describes the different ways that the Kongolese endowed their nkisi

with a persona, and he uses the Lamam manuscripts to demonstrate how the Kongolese viewed

the nkisi figure as a person. The nkisi nkondi was a vessel for the spirit that resided within it,

and by driving an iron spike into the body it angered the spirit. This action caused the enraged

spirit to seek vengeance against the wrongdoer. MacGaffey concluded that the personhood of

the Minkisi in the Congo was not an exclusively Congolese phenomenon but also occurred in

European culture. The personification method of the minkisi was an exclusively Congolese

phenomenon.

The Congolese world of magic and witchcraft deals with spiritual objects that contained

large amounts of power and social influence. An artesian created each nkisi, and the owner

would buy and take the figure to an Nganga. The Nganga performed a ritual ceremony and

endowed the nkisi figure with a spirit. Once the spirit was inside the figure the figure became a

vessel for the spirit, and the visible vessel for the spirit’s social interactions. The minkisi

figures were a popular topic for African art historians, who studied the aesthetic traits of the

4 Wyatt MacGaffey, “The personhood of Ritual Objects: Kongo “minkisi””, Etnofoor 3, 1 (1990): 45-61.

Chuhna 6

figures. The creation of the minkisi figures and their different visual attributes were a topic of

examination by African art historians.

This paper will examine two different kinds of minkisi and elaborate on what their roles

were within the Congolese communities they resided in. It will also discuss how the westerns

in the 20th century viewed the minkisi during the Harlem Renaissance. This paper will do this

by using both written and physical primary sources. The written primary sources are the K.E.

Lamam manuscripts and the descriptions Reverend J.H. Maw collected during his six years in

the Congo. The physical primary sources are two nkisi figures, one of which is in the

collections of the Carlos Museum at Emory University and the other is in the collection at the

Brooklyn Museum in New York.

The Primary Sources: What their Roles and Uses in the Congo

Chuhna 7

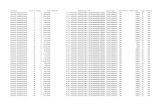

Figure 1 is of an nkisi nkondi figure from the Congo region. The figure is a male statue

that was stuck with 47 pieces of metal (nails and knives). The pieces of metal are of various

sizes and dimensions, but they are all rusty. Three of the pieces of metal have things attached

to them, the objects vary from white to black to red (see Figure 3). There is a mirror in the

navel/stomach area that is dirty and no longer shiny. The arms run out along the body and the

hands are connected to the figures hips. The head has headdress that four flat parts that stick

above the head, and the mouth is open with teeth and tongue showing. There are bracelets

around each bicep. The figure also seems like it was

painted or stained white on most of its body. The

figure’s

measurem

ents are 33 7/8” x 13 ¾” x 11”. The figure is from the

19th century, and joined the museum collection in 1922.

This

nkondi

figure is

located at

the Brooklyn Museum and is a part of the African

Art collection.

Figure 1 Nkisi Nkondi, 18th-19th century, Brooklyn Museum

Chuhna 8

Nkondi meant “a hunter who leaves to hunt in secret”5, the nkondi’s purpose was to

track down unidentified wrongdoers. The nkondi figures often had menacing facial expression

and way stance of the body also was a sign of authority and aggression. Not all the nkondi

figures looked the same, but there were some stylistic traits that were common among many of

the figures. “The figure is often that of a human being, signifying aggressive intent by its

uplifted spear, hands on the hips, or bared teeth.”6 Image one shows to aggressive traits, the

hands on the hips and the teeth showing. The statue’s overall design was did not just signify

aggression, but these “particular statue[s] has a

frightful aspect, people will respect it and think that if

it attacks it will change [the victim] to be like itself . . .”7 Even though the Kongolese would

fear and respect the figures, the figures were just ordinary objects. The figures were ordinary

objects until the infusion of the three domains of nature and the completion of the activation

ritual. The figures gained its power from the spirit that inhabited the figure, and that power the

spirit brought was where most of the fear originated.

Using the nkondi figure meant that the practitioner had to drive pieces of iron into the

figures body while telling it a target. In some case the practitioner did not know who the target

was and so the practitioner would tie something that either belonged to the suspect or was from

the scene of the crime. The practice of driving the nails was called “koma nloko, 'to nail a

curse.'”8 This nkondi was not used as much as some from the Congo, as seen in Figure 3.

5 Volavkova, “Nkisi Figures of the Lower Congo”, 54. 6 MacGaffey, Kongo Political Culture: The Conceptual Challenge of the Particular, 101. 7 Konda, from Kinkenge, Cahier 120, as in Wyatt MacGaffey, “Complexity, Astonishment and Power.

The Visual Vocabulary of Kongo Minkisi”, 199. 8 MacGaffey, “The personhood of Ritual Objects: Kongo “minkisi””, 54.

Figure 2 Nkondi, showing material attached to metal

Chuhna 9

Figure 3 Nkisi Nkondi, 18th-19th Century, Yale University Museum

Figure 4 Ekishi Omoi, 18th - 19th century, Emory University

“In the body of the nkisi iron spikes are driven so that

Nkondi may be angry on account of its wounds and work

vigorously in the body of its victim, who is the occasion for

the spikes to be driven; the nkisi attacks the wrongdoer, so

that the spike may come out.” 9 When the piece of iron was

driven into the nkondi’s body it wanted revenge, and so the

nkondi would go forth and attack the wrongdoer.

The nkondi had three main purposes in the social

sphere of the Congo; the first was to pursue unknown

wrongdoer, the second was when parties entered into a

contract, and the last was when someone was seeking protection for themselves. The nkondi

were so effective, because the Kongolese did not want it to come after their lives. “‘Nkondi

Mukwanga had pursed me here, surely I will die in the same fashion.’ Not long after he will

feel a burden on his back, a pain in the blood, blood will gush from his nose, and he will die of

his affliction.”10 The nkondi were powerful minkisi that helped dispense justice in their local

communities.

Figure 4 is of a healing nkisi figure, named Ekishi

Omoi, from the Congo region. Ekishi Omoi is a standing

wooden figure with its arms at its side. The figure has a

woven raffia cloth covering, and a reed peel holds it on.

9 Demvo in Kingoyi, Cahier 27, Nkisi Nkondi, as in Wyatt MacGaffey, “The personhood of Ritual

Objects: Kongo “minkisi””, 54. 10 MacGaffey, Kongo Political Culture: The Conceptual Challenge of the Particular, 103.

Chuhna 10

Figure 5 Ekishi Omoi, close up of the face. Can see cracked mirror, month area, and ear holes

The figure has glued on black hair, looks like real hair but unsure, the hair is falling off in

some areas. There are mirrors in the eye sockets, and it looks like there is stuff behind the

mirrors. The right eye mirror has a crack, and both mirrors are degrading (see figure5). There

is a hole where a mouth should be, and it looks like there something there. After looking at the

accession file I know that there was a cowery shell there when they got it, but it fell out. The

ears a hollowed out on the side of the head. There is a necklace with small beads on it, and the

beads are red and yellow with one white bead. The head appears painted at one time, but it has

faded, there are still visible signs of red and white pigments. The figure’s measurements are

13” x 5 ¼”. The figure is from the late 19th century or early 20th century. It was a gift to the

Emory University Museum of Art and Archeology in 1935 by Reverend J.H. Maw, along with

descriptions of the uses of nkisi Omoi.

A healing nkisi “is the thing we use to help a

person when that person is sick and from which we

obtain health … to protect the human soul and guard

it against illness for whoever is sick and wishes to

be healed. Thus an nkisi is also something which

hunts down illness and chases it away from the

body.” 11 The power of a healing nkisi would

normally come from the “below” spiritual domain.

The spiritual domain had two sections of power,

11 Robert Farris Thompson, Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy, New

York: Random House 1983, 117.

Chuhna 11

“the above (ku zulu) and the below (ku nsi).”12 The above was the sky and celestial waters and

were masculine and violent in nature. As the below was the earth and terrestrial waters and

were feminine and benevolent. The healing nkisi’s power was from the “below”, they were not

aggressive nor were they meant to seek justice. Their purpose was help better the community

or the owner.

This type of minkisi figure was a part of the everyday occurrences of the community it

resided. The healing minkisi used to help with anything from helping replenish life into

someone’s crops to helping someone live a long life. In some cases help prevent someone

getting poisoned.

“If a person has enemies and fears that he will be poisoned by them he will

go to the witch doctor and tell him. The witch doctor will tell Omoi and she

will tell the man that he must pay the 15.00 francs or the equivalent. The

man will pay the 15.00 francs and the witch doctor will give him some

bitter food as an example of food that has been poisoned. The man will eat

it and thus know that if he is ever given food that has that bitter taste that he

must not eat it. However, if he is ever given any food that has poison in it

that isn’t bitter he will vomit it up and not die because he has made the gift

of 15.00 francs to Omoi.”13

This description is from the accession file that was with nkisi Omoi. For this kind of nkisi to

work the practitioner had to make some kind of sacrifice to it, such in this case money, but

12 MacGaffey, “The personhood of Ritual Objects: Kongo “minkisi””, 50. 13 J.H. Maw, Power of the Ekishi Omoi, Doll Idol (Ekishi Omoi) accession file, 1935, Emory University

Museum of Art and Archaeology.

Chuhna 12

other times it would be killing an animal or even food. These sacrifices were from the person

that was asking the witch doctor to perform the ritual. The minkisi figures had power and

influence on all level of the Congolese societies, and they were “used to ensure personal

protection, healing, or good fortune…”14 The use of the minkisi figures was a part of everyday

life, they were an integral part of the Congolese society. The healing nkisi were viewed as a

chief figure in the community.

20th Century Western views of Minkisi

In the western world has viewed the artifacts and objects of Africa as valueless and

garage. Early European traders “in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries deemed the … African

societies to be founded on the valuing of trifles and trash.”15 The early European traders would

normally see no value in the artifacts of the African world, but as time went on and they saw

more of the African societies they started to find their “art” to be interesting and “exotic”.

When dealing with African artifacts the Western world called art even when they have other

purposes. Such as the minkisi figures they called art and displayed in art museums all around

the western world. Many of the Congo spiritual items are visually appealing and have a many

levels of visual effects happening in one item. When these items on display in museums the

exhibits are normally “constructed with great care in order to produce a visual effect…”16

Items like the minkisi figures are not pieces of art in their native setting, they are powerful

spiritual objects that contain living souls. Although many museums do include that they are

spiritual items on their display tag, but they often do not have any type of background

14 Young, Rituals of Resistance: African Atlantic Religion in Kongo and the Lowcountry South in the Era of Slavery, 111.

15 Wyatt MacGaffey, “African Objects and the Idea of Fetish”, RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, no. 25 (1994), 127.

16 MacGaffey, “Complexity, Astonishment and Power. The Visual Vocabulary of Kongo Minkisi”, 189.

Chuhna 13

information on their display card. For most patrons of art museums they do not know what

these items are and only view them as “art”. Some museums have large collections of African

artifacts that they display, and in some cases the museums have sent people to Africa to collect

these items for display.

In the western world non-European art got classified as exotic art and the stranger and

less western it looks the more exotic it becomes. These items will get display at museums and

will be the focal point of a people’s whole culture. Europeans have not always been the best at

trying to understand what is different to them. Frequently the displayed artifacts will have

“details on the peoples and cultures that artifacts are said to represent. Notions of function,

context original culture, and authenticity shroud the legitimacy of such objects”17 Museums

will give only a brief description of a non-European object, and not always full information.

Art galleries though do not really look at the context of the artifact, instead they will classify

objects based on the objects visual appearance. Some exhibits do focus on both the visual

appearance and the cultural contexts, but they question and blur art and ethnography in their

displays.18 The collectors of these collections had interests of their own when going to Africa

and collecting these objects. Arnold Ridyard was a collector for the Liverpool Museum, and

“he had a taste for wooden masks and figurative sculptures.”19 Ridyard’s focus on figure

collection explains why there are so many idol figures and Minkisi in museum collections. Just

about any African exhibit will have figures in them, and often if the exhibit has Congo artifacts

there will be an nkisi among them. With the large number of African artifact, especially in

17Louise Tythacott, “The African Collection at Liverpool Museum”, African Arts 31, 3 (1998):, 18.

18 Tythacott, “The African Collection at Liverpool Museum”, 21. 19 Tythacott, “The African Collection at Liverpool Museum”, 22.

Chuhna 14

figures, how did it influence the African American art movements, such as the Harlem

Renascence, or did it?

The Harlem Renaissance, which a blossoming of black artists, was a movement by

African Americans to revitalize their African roots in the arts. The movement was not just the

visual arts but also literary arts and theatrical arts. Among this movement there was a growing

Pan-Africanism among the African American artist, of all the arts. Artist Meta Vaux Warrick

Fuller was sculptor, saw her works as being “truly Pan-Africanism works of art.”20 The ideas

of getting back to their African roots was a wide spread idea, and they were also using it help

build their own section of the art community. The African American artists were wanting to

use their ancestral roots for their inspiration of their arts. But how did they see African art and

what kind of art were they viewing?

For the African Americans during the Harlem Renaissance many of them did not go to

Africa to view the arts themselves, instead they viewed the arts in museum collections. The

African art “was beginning to enter American museums and was accessible through the

collections of prominent avant-garde art dealers.”21 These collections allowed the upcoming

African American artists to see what their “ancestral heritage” was and allowed them “to return

to the ancestral arts of Africa for inspiration.”22 They were viewing only selected pieces of art

that were visually appealing and meant to get people’s attention. The collectors were not

always concerned with what the object’s purpose was, but there were some collectors, like J.H.

Maw, who did collect the objects and the stories that belonged with the object. The minkisi

20 David C. Driskell, et. all, Harlem Renaissance: Art of Black America, 108. 21 David C. Driskell, David L. Lewis, and Deborah Willis, Harlem Renaissance: Art of Black America,

New York: Studio Museum in Harlem, 1987, 105. 22 David C. Driskell, et. all, Harlem Renaissance: Art of Black America, 106.

Chuhna 15

figures though did not have an impact on the Harlem Renaissance (that I was able to find), but

objects such as masks, headdresses, jewelry, and paintings had more of an impact on the

Harlem Renaissance. Even though the African Americans were attempting to return to their

roots in the arts, much of their art still had western influences mixed in, and unlike the art of

the Harlem Renaissance “the nkisi figures themselves, however, remained African.”23 The

minkisi figures were a fascination for Westerns, and viewed as exotic and fetishes. But the

minkisi figures did not really ever influence American art to any significant degree.

Conclusion

The Minkisi figures were an integral part of the Congolese societies, and they had great

power. There were four categories of minkisi in the Congo, two of them were the healing

classification and the Nkondi. The nkisi nkondi had a spirit from the power of the above,

which meant that the spirit was masculine and had violent tendencies. As the healing nkisi

(Ekishi Omoi) had a spirit from the power of the below, which meant that the spirit was a

feminine and non-violent. The two different figures had their purposes in the communities: the

nkondi’s purpose was to help seek justice against wrongdoers and the Ekishi Omni’s purpose

was to help heal the living. The nkondi would help find an unknown suspect, be a part of treaty

signings, and help with person al protection. Ekishi Omoi would help heal the living, and that

meant helping to heal humans, help protect against poison, and even help revitalize a farmer’s

crops. The minkisi figures were a part of the community they resided in and viewed as a living

object. The figures themselves did not have power before the spirit entered into the figure’s

body, but the figure themselves did become a fascination of the Western world and pieces of

art.

23 Volavkova, “nkisi Figures of the Lower Congo”, 59.

Chuhna 16

The early European explores first saw the Minkisi figures and other African figures as

glorified garage, but around the late nineteenth century museums and collectors started

wanting them. Westerns called the Minkisi exotic and fetishes, these objects viewed from an

aesthesis view and not a cultural context. The Museums might have some information about

the object on a display tag, but the information was minimal and did not have much in

background information. The other African arts, such as masks, headdresses, jewelry, and

paintings, were collected, too. These objects helped influence Western arts to some ends, but

when it came to African American art movements, such as the Harlem Renaissance, they were

more heavily influenced by the African objects that were in the Museum collections. However

the Minkisi figures were not a part of the influential base for the Harlem Renaissance, instead

they used more of the African paintings, masks, and jewelry in their arts. But did the Harlem

Renaissance really help African Americans get back to their ancestral roots of art? Getting

back to the African ancestral roots of arts was difficult, because many of the people that were

collecting the objects for the museums would have their own likes and dislikes. So this would

limit the samples that the African Americans could view. Many of the African American works

had influences from the African art, but they still had Western influences ingrained in the

works. The minkisi figures unfortunately were not drawn upon by African American artists

during the Harlem Renaissance. The figures themselves remained an African stylized object

that the western world has turned into an exotic fetishism for museums.

Chuhna 17

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Doll Idol (Ekiski Omoi). Gift of Reverend J.H. Maw, 1935.1.20. Emory University Museum of Art and Archelogy.

Male Figure (Nkondi). Yale University Art Gallery, Charles B. Benenson, B.A. 1933, Collection, (2006.51.246).

Maw, J.H. Power of the Ekishi Omoi. Doll Idol (Ekishi Omoi) accession file,1935. Emory University Museum of Art and Archaeology.

Power Figure(nkisi nkondi). Museum Expedition 1992. Robert B. Woodward Momorial Fund, 22.1421. Brooklyn, New York.

Secondary Sources

Driskell, David C., David L. Lewis, and Deborah Willis. Harlem Renaissance: Art of Black America. New York: Studio Museum in Harlem, 1987.

Gubert, Betty. “Three Songye and Kongo Figures”. African Arts 15, 1 (1981): 46–88.

MacGaffey, Wyatt. “Fetishism revisited: Kongo “nkisi” in Sociological Perspective”. Africa: Journal of the International African Institute 47, 2 (1977): 172-184.

______________. “Complexity, Astonishment and Power. The Visual Vocabulary of Kongo Minkisi”. Journal of Southern African Studies 14, 2 (1988): 188-203.

______________. “The personhood of Ritual Objects: Kongo “minkisi””. Etnofoor 3, 1 (1990): 45-61.

Chuhna 18

_______________. “African Objects and the Idea of Fetish”. RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, no. 25 (1994): 123–31.

______________. Kongo Political Culture: The Conceptual Challenge of the Particular. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000.

Thompson, Robert Farris. Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy. New York: Random House, 1983.

Tythacott, Louise. “The African Collection at Liverpool Museum”. African Arts 31, 3 (1998): 18–94.

Volavkova, Zdenka. “Nkisi Figures of the Lower Congo”. African Arts 5, 2 (1972): 52-84.

Young, Jason R. Rituals of Resistance: African Atlantic Religion in Kongo and the Lowcountry South in the Era of Slavery. Louisiana State University Press, 2007.