Milhaud · 2019. 3. 18. · Darius Milhaud 1892-1974 Chamber Music Suite Op.157b for violin,...

Transcript of Milhaud · 2019. 3. 18. · Darius Milhaud 1892-1974 Chamber Music Suite Op.157b for violin,...

Pierluigi Bernard clarinetMauro Tortorelli violin & viola · Angela Meluso piano

MilhaudCHAMBER MUSIC

Darius Milhaud – Music for Violin, Clarinet and PianoCan music be defined as a means of communication consisting of basic elements that have no absolute meaning? If we accept music to be a non-semantic language, is it nevertheless possible for listeners to share much the same experience and to attribute more or less the same meaning to what they hear?

The question is essential, because an affirmative answer inevitably implies the problem of establishing an agreed system of significance that allows the composer to get his message across. Communication of this sort involves not only the content itself, but also the effect that it will have on the listener.

In his long, fruitful career, Darius Milhaud always had a clear idea of what he wanted to obtain with his work as a composer. Moreover, he also knew how to achieve what he had in mind, manipulating different musical languages, systems and forms with highly effective coherence. Such was the essence of his art.

Although he was a man of the 20th century, when ideologies permeated daily life and conditioned the way values were attributed to artistic creations, including music, Milhaud rejected the role of the artist as a vehicle for social or political convictions. Moreover, he also steered clear of easy solutions and superficiality. As a result, he has probably not enjoyed the critical attention that he certainly deserves.

Some would claim that he actually wrote too much, that the over 450 catalogued works could only speak for a lack of real inspiration. Others have insisted that his style was too simple and varied. In both cases the critics are missing the point: Milhaud stood by his own conviction that his compositions should be intelligible without being obvious, and that to achieve this he could turn his compositional skill and intellectual honesty to address a wide range of different ideas, sources and structures, without foregoing anything in terms of coherence.

Listening to this second collection of chamber works by Milhaud is an opportunity for appreciating their refined qualities, including the clear, rational use of irregular rhythmic elements, the tendency to elude and enrich the connections intrinsic to key by layering harmonic sounds in the construction of chords, and sliding between

Darius Milhaud 1892-1974Chamber Music

Suite Op.157b for violin, clarinet and piano1. Ouverture (Vif et gai) 1’352. Divertissement (Animé) 3’033. Jeu (Vif) 1’304. Introduction et Final

(Moderé-Vif) 5’31

Danses De Jacarémirim Op.256 for violin and piano5. Sambinha 1’356. Tanguinho 2’147. Chorinho 1’24

Sonatina Pastorale Op.383 for violin solo8. Entrée 1’319. Romance 2’2010. Gigue 1’03

11. Elégie Op.251 for viola and piano 3’24

12. Farandoles Op.262 for violin and piano 3’49

13. Caprice Op.335a for clarinet and piano 1’59

Sonatine Op.100 for clarinet and piano14. Très rude 3’2615. Lent 4’0316. Très rude 2’41

17. Duo Concertante Op.351 for clarinet and piano 6’36

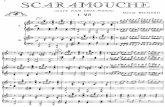

Scaramouche Suite Op.165d for clarinet and piano18. Vif 3’0619. Modéré 4’2020. Brazileira 2’26

Mauro Tortorelli violin, viola · Pierluigi Bernard clarinet · Angela Meluso pianoPierluigi Bernard plays on a Clarinet, Peter Eaton (Élite model, English wide bore)

Mauro Tortorelli plays on a viola, Giuseppe Arrè (2000, Cremona)

different tonal spheres, some of them distant one from another, rather than adopting more or less conventional modulations.

Composed in 1936, Suite Op.157b is one of the most important works for this combination of instruments, the repertoire for which grew considerably during the course of the 20th century, starting with Max Bruch’s suite of eight pieces for violin, clarinet and piano published in 1910. In the first half of the century, composers such as Béla Bartók, Charles Ives and Aram Khachaturian also wrote for this trio of instruments, while Alban Berg and Igor Stravinsky rearranged certain of their existing compositions for it.

The Ouverture that introduces the Suite is extremely lively, with reiterated dactylic rhythmic figurations (long – short – short). The timbres of the violin and clarinet are used together to great effect, creating an evident allusion to the tango and to the sound of the bandoneon squeezebox. The Divertissement - Animé that follows opens with a dialogue between violin and clarinet that heralds the entry of the piano in a paradoxically calm atmosphere, where the only real animation is the dactylic rhythm.

As the title suggests, Jeu, which is the third movement of the Suite, is deliberately ironic and playful. Entirely played by the violin and the clarinet, it also features dactylic rhythm, right from the first bars in the violin. From the structural point of view, each of the three sections develops rhythmic melodies first presented in the previous movements to create a light-hearted musical puzzle in which the heady tango of the initial Ouverture becomes a sort of Bourée, which in its turn gives way to an elegant Gavotte. Milhaud clearly had fun putting his skill in handling his chosen material to such good use.

The Finale starts with a slow movement in which all four instruments largely share the same rhythm. Yet the majestically emphatic nature of the introduction conceals an interesting rhythmical exploit, whereby what comes across as a symmetrical, regular development actually embodies an essentially irregular 5/4 tempo that subverts the original perspective and leads to the 6/8 rhythm of the finale. Here the first section

is a Gigue with a central part that turns into a sort of folk song teasingly interrupted by a glissato on the piano and a double trill on the clarinet and the violin. Milhaud also delights in adding surprise elements to the return of the Gigue, inserting a brief contrasting feature and ending with a chord that layers an F sharp over a G so that the piece finishes in a suspended state.

Jacarèmirim is the word used in Brazil to refer to a small alligator with big eyes and a long snout. Because of its size, it is not considered particularly dangerous. The pieces that make up the unusual suite for violin and piano of the same name are also short. They consist of three dances composed in 1945, although Milhaud’s interest in Brazilian folk music began thirty years earlier, during this first stay in South America, when he went there to work with Paul Claudel. Known as MPB, Brazilian folk music features considerable harmonic and rhythmic complexity. Its elevated compositional quality derives from the fact that it is the fruit of osmosis between western “Salonmusik” (Waltz, Mazurka, Lieder) and the polyrhythmic structures of African music. This must have fascinated Milhaud, who often turned to that musical universe for inspiration, freely reworking the “borrowed” elements to highly individual effect.

The Sonatina Pastorale for solo violin composed in 1959 is also relatively short, though far from simple. As with certain earlier works, including Ravel’s Sonatina, the composition as such and the requirements of performance all reveal a degree of complexity. Divided into three sections, the Sonatina Pastorale opens with a lively introduction followed by a cantabile section. In both cases the violin part is like a small homage to the style of Paganini, whose works Milhaud had studied in depth, transcribing in 1927 the three Capricci in highly original terms, with the evident aim of expanding the range of timbre and harmony. The Gigue that concludes the Sonatina is like a pastorale that terminates in a sudden, rapid episode without any trace of emphasis.

The Élégie for viola and piano was composed in 1945. Several years later, in 1965, Milhaud returned to the genre, composing a second Elegy for viola and percussion.

The seven years spent in the United States following the outbreak of the Second World War had been highly fruitful, as the freedom of the compositional solutions found in this piece clearly reveal. It conjures up an aura of lyrical melancholy, yet never in obvious terms, since Milhaud did not seek to astound audiences with easy effects. Instead he would captivate his listeners with his subtle use of compositional devices, such as the pizzicato in the viola in the central part that make the return to the subject particularly fascinating.

Written in 1946, Farandoleurs is a playful, heartfelt homage to the earliest Provençal dance form. Many composers had turned their hand to it, including Bizet, Tchaikovsky, Gounod and D’Indy, but none with such a deep sense of participation and feeling. While Milhaud was living as an exile in the United States, his Provençal origins meant that he was able to identify more closely with his fellow countrymen and women as they formed a circle to enact the dance of life and death, accompanied by flutes and percussion.

The Caprice for clarinet and piano 335a was composed in 1953, and published the following year. It is also brief, and although its ABA structure is simple enough, Milhaud typically manages to alter the rhythmic and melodic symmetry of the piece without entirely subverting it, so that what appears to be somewhat insignificant thematic material actually turns out to be a source of interest for the listener.

Written in 1927, the Sonatina Op.100 has a slightly misleading title, since the tradition of the Sonatina in France of the early 1900s has little in common with compositions of the same name dating back to the late ‘galant’ and classical periods. From the point of view of performance, this is actually a somewhat tricky work: the layering of harmony and different rhythms that is a feature of the first and last movements, along with the pensive melodiousness of the central section, call for meticulous execution and an ability to handle with nonchalance the spiky dissonance that abounds throughout the score.

The last years of Milhaud’s life were not easy. His arthritis had finally confined him to a wheelchair, yet despite this he continued his activities as a composer,

conductor and teacher. Many of the compositions of the last period, including the Duo concertante for clarinet and piano Op.351 of 1956 (like Olivier Messiaen’s Le Merle Noir, it had been a test piece for the Paris Conservatoire) convey a strong desire to play with sound, revealing Milhaud’s total imperviousness to all late-romantic tendencies.

What comes to the fore in Milhaud’s compositions is rational thought and a precise expressive intent, which prevail over any manifestation of the self. The listener is thus free to experience sensations and feelings, or otherwise. They are never imposed a priori. Thus the Duo concertante opens with an echo of a Provençal folk motif that the composer manipulates with evident glee. This is then followed by a more lyrical and slightly melancholic section, in which the melody is entirely entrusted to the clarinet, while the piano simply acts as an accompaniment. The initial subject returns in the last section, in keeping with the classic ABA structure.

There are various versions of Scaramouche, the first of which was a suite for two pianos composed in 1937 at the behest of Marguerite Long. A second version, this time for saxophone and orchestra, followed in 1939, then the arrangement for clarinet and piano, and finally the one for sax quartet.

The title of the piece does not refer directly to the famous Commedia dell’Arte clown character, but to the fact that at the time Milhaud had recently completed the music for an adaptation of a play by Molière to be performed at the Scaramouche Theatre in Paris. He thus returned to what he had just finished composing to shape two of the three movements of the suite. The central movement, on the other hand, derives from another score written for the stage: “Bolivar”, on texts by the French poet and playwright born in Uruguay, Jules Supervielle.

The composition soon became one of Milhaud’s most famous works, meeting with great success on both sides of the Atlantic. The salient feature of the work is, once more, the use of tonal and polyrhythmic layering, yet this is only a surface impression. Closer attention reveals a curiously intimate ability to involve the listener in a form of rational appreciation, without imposing a particular point of view. Everyone is free

una scontata e banale superficialità, non ha forse avuto l’attenzione e il rispetto che avrebbe certamente meritato.

Troppo prolifico? Oltre 450 opere catalogate hanno reso sospettoso chi ha sempre giudicato in termini positivi i compositori alla ricerca di genuine ispirazioni ma alle prese con il problema della pagina bianca.

Linguaggi troppo facili ed eterogenei? Inconsistente accusa fatta a chi ha sempre creduto nella possibilità di comporre per essere compreso, senza mai essere banale o scontato, utilizzando con abilità e onestà intellettuale suggestioni diverse in strutture coerenti.

L’ascolto di questa seconda raccolte di composizioni cameristiche del musicista provenzale permette una più precisa e puntuale scoperta del loro valore e delle loro raffinate qualità che, fin dagli esordi si sono contraddistinte per un uso chiaro e razionale degli elementi ritmici irregolari, la tendenza ad eludere, arricchendoli, i nessi propri della tonalità, con l’uso di sovrapposizioni dei suoni armonici nella costruzione degli accordi e, infine, slittamenti, più che vere e proprie modulazioni più o meno convenzionali, verso differenti ambiti tonali, anche lontani.

La Suite Op.157b, composta nel 1936, è una dei brani più importanti per questo particolare organico il cui repertorio si è notevolmente arricchito nel corso del sec. XX.

Il primo esempio è la suite di otto brani che Max Bruch scrisse specificatamente per violino, clarinetto e pianoforte nei primi anni del secolo e che pubblicò nel 1910.

Nel corso della prima metà del ‘900, compositori come Béla Bartok, Charles Ives, Aram Khachaturian hanno scritto per questa tipologia di trio. Alban Berg e Igor Stravinsky hanno invece trascritto proprie musiche per questo organico.

La prima parte della Suite (Ouverture) ha un andamento estremamente vivace, caratterizzato dalla reiterazione della figurazione ritmica dattilica (lunga – breve breve), e da una scrittura che sfrutta al meglio la combinazione timbrica tra il violino e il clarinetto: il tutto produce una più che evidente allusione alla forma del tango e al suono del bandoneon.

La seconda parte della Suite (Divertissement – Animè) si apre con un dialogo

to imagine what he or she likes. Had Milhaud ever meant to invest his music with a message, it would have probably been: if freedom consists in the possibility of making a choice, then the listener must take on the responsibility for attributing meaning to what he hears, and the composer for making this possible.Francesco Maschio Translation by Kate Singleton

Musiche per Violino, Viola, Clarinetto e Pianoforte di Darius MilhaudE’ possibile definire la musica come un medium di comunicazione i cui elementi basilari non sono portatori di significati assoluti, dunque asemantici? E che tuttavia consentono all’ascoltatore, attraverso un processo di condivisioni più o meno consapevoli, di attribuire significati a ciò che ascolta?

La risposta a questa domanda è dirimente, nel senso che chi condivide la sua affermazione deve necessariamente porsi il problema di quanto e come un codice di attribuzione di significati possa essere condiviso e quanto possa essere efficace per permettere al compositore di raggiungere i propri obiettivi di comunicazione.

Perché è importante avere chiari nella propria testa gli obiettivi che si vogliono raggiungere prima di comunicare qualcosa, altrimenti si rischia di fallire, di non essere capiti, di essere fraintesi.

Darius Milhaud, nella sua lunga e prolifica carriera, ha sempre dimostrato di avere le idee molto chiare sugli obiettivi del proprio lavoro di compositore e di come raggiungerli, manipolando opportunamente linguaggi, sistemi e forme musicali e in modo coerente ed efficace: ad arte, appunto.

Milhaud ha vissuto nel XX secolo, periodo in cui le ideologie hanno pervaso il vivere quotidiano e hanno condizionato anche i processi di attribuzione di valore alle produzioni artistiche, comprese naturalmente quelle musicali.

Di conseguenza chi, come Milhaud, ha eluso o disatteso il ruolo di messaggero di contenuti politico/sociali dell’artista novecentesco, senza peraltro mai scivolare verso

Le tre danze sono state composte nel 1945 ma l’interesse di Milhaud per la Musica Popolare Brasiliana (MPB) risale a circa un trentennio prima, durante il suo primo periodo trascorso in Sudamerica, come collaboratore di Paul Claudel. La MPB si caratterizza per un livello compositivo molto alto, sia dal punto di vista della complessità armonica che ritmica. E’ il frutto di un processo di osmosi tra la “Salonmusik” occidentale (Valzer, Mazurke, Lieder) e le strutture poliritmiche africane: proprio questo aspetto deve aver affascinato Milhaud, che spesso ha liberamente reinterpretato quel mondo musicale, riproponendone una lettura personalissima e affascinante.

Anche la Sonatina Pastorale per violino solo, composta nel 1959, ha dimensioni ridotte, tuttavia, come alcuni illustri precedenti quali, fra tutti, quello della Sonatina di Ravel, alla brevità e concisione non corrisponde certamente una semplificazione della composizione né, d’altra parte, dell’esecuzione stessa.

Suddivisa in tre sezioni, la Sonatine pastorale si apre con un’introduzione brillante a cui segue una sezione cantabile: in entrambe queste parti la scrittura violinistica è un piccolo omaggio allo stile paganiniano, che Milhaud aveva studiato in modo approfondito, trascrivendo nel 1927 tre capricci in termini estremamente originali con l’evidente intento di amplificarne le risorse timbriche e armoniche. La Giga che chiude la Sonatina ha il carattere tipicamente pastorale e termina con un gesto rapido, improvviso, molto poco enfatico.

L’Elegie per viola e pianoforte fu composta nel 1945: qualche anno dopo, nel 1965, Milhaud tornò a frequentare questo particolare genere musicale componendo una seconda Elegia per viola e percussioni. I sette anni di permanenza negli Stati Uniti a seguito dello scoppio della seconda Guerra Mondiale furono assai fecondi: l’estrema libertà con cui Milhaud poté agire, anche dal punto di vista delle soluzioni compositive, si riverbera anche in questo brano. La liricità malinconica che lo caratterizza è assai misurata: al solito Milhaud non cerca facili effetti ma riesce a spiazzare l’ascoltatore con abilissimi accorgimenti quali, ad esempio, il pizzicato della viola nella parte centrale, che rendono niente affatto banale la riproposizione del tema.

tra il violino e il clarinetto che prelude all’intervento del pianoforte in un clima paradossalmente calmo, assai poco animato se non nell’utilizzo, ancora una volta, del ritmo dattilico,

L’intento ironico e giocoso è totalmente esplicito nella terza parte della Suite (Jeu), affidata interamente al violino e clarinetto: anche qui si ascolta la prevalenza del ritmo dattilico, fin dalle prime battute nella parte del violino.

La struttura di questa terza parte è speculare e ciascuna delle tre sezioni che lo compongono utilizza elementi ritmico melodici presentati nelle precedenti parti della Suite. Si tratta appunto di una specie di giocoso puzzle musicale che trasforma il vertiginoso tango dell’Ouverture iniziale in una sorta di Bourrèe che cede a sua volta il passo ad un’elegante Gavotta: Milhaud gioca e si diverte nello sfruttare sapientemente le sue capacità manipolatorie.

Il finale è introdotto da un movimento lento, dalla prevalente condotta omoritmica di tutti gli strumenti: il carattere maestosamente enfatico di questa introduzione nasconde però un particolare. Per quanto all’ascolto possa essere percepito come un movimento dall’andamento regolare, simmetrico, le battute che lo compongono sono in un tempo tipicamente irregolare (5/4).

Ancora un rovesciamento di prospettiva, dunque, che prelude al vero e proprio finale, in 6/8: la prima sezione è una Giga che, nella parte centrale, si trasforma in una sorta di graziosa chanson popolare improvvisamente e fastidiosamente interrotta da un glissato del pianoforte e un doppio trillo del clarinetto e del violino. Anche nella ripresa della Giga, Milhaud si diverte a mescolare le carte, inserendo un breve elemento di contrasto e chiudendo, in maniera ironica, con un accordo che sovrappone al sol basso un la e un fa diesis, lasciandone dunque sospesa la risoluzione.

Il Jacarèmirim è il nome con cui i brasiliani chiamano un piccolo alligatore dai grandi occhi e dal lungo muso: date le sue dimensioni non è particolarmente pericoloso.

Dunque, così come le dimensioni del rettile, i brani che compongono l’insolita suite di danze per violino e pianoforte sono altrettanto brevi e i loro titoli alludono alla loro durata.

Il suo Ego non emerge mai dalle sue composizioni, frutto invece di un pensiero razionale e di un preciso intento espressivo che lascia all’ascoltatore la libertà e la responsabilità di provare emozioni, senza mai volerle imporre a priori.

Così il Duo concertante si apre con la citazione di un motivo popolare provenzale che Milhaud manipola con grande divertimento, a questa sezione segue una parte più lirica e vagamente malinconica in cui la melodia è totalmente affidata al clarinetto e il piano svolge una semplice funzione di accompagnamento. Il tema iniziale viene riproposto in chiusura, secondo la classica struttura ABA.

Esistono diverse versioni di Scaramouche: la suite fu originalmente composta nel 1937 per due pianoforti, dietro richiesta di Marguerite Long. Una seconda versione fu approntata da Milhaud per sassofono e orchestra nel 1939, seguirono poi la versione per clarinetto e piano e quella per quartetto di sassofoni.

Il titolo non fa riferimento diretto alla celebre maschera della commedia dell’arte ma al fatto che in quel periodo Milhaud aveva scritto da poco delle musiche di scena per un adattamento di una pièce di Molière per il teatro Scaramouche a Parigi.

Partendo da quei materiali, Milhaud costruì due dei tre movimenti della suite; il movimento centrale ha invece origine da un’altra musica di scena scritta per uno spettacolo teatrale, “Bolivar”, del poeta e drammaturgo di origini uruguayane Jules Supervielle.

La composizione è presto diventata una delle più celebri e conosciute di Darius Milhaud, ottenendo un grande successo anche oltre oceano: l’uso delle sovrapposizioni tonali e delle poliritmie sono la caratteristica più evidente di questa suite, come di gran parte della produzione del compositore provenzale, ma è solo l’immagine di superficie, ciò che per prima cosa è possibile percepire.

Andando maggiormente in profondità emerge una caratteristica più peculiare, intima: la capacità di sorprendere piacevolmente e, contemporaneamente, di sollecitare l’approccio cognitivo dell’ascoltatore senza costringerlo a condividere il punto di vista del compositore, lasciandolo libero di immaginare ciò che vuole. Se davvero Milhaud avesse mai voluto inserire messaggi o contenuti politici nella

Risale al 1946 la composizione di Farandoleurs: omaggio divertito e appassionato al più antico e caratteristico ballo provenzale. La danza ha avuto molte reinterpretazioni, da Bizet a Tchaikoskji, da Gounod a D’Indy ma certamente l’omaggio del provenzale Milhaud, in esilio negli Stati Uniti, ai compaesani alle prese con la danza in circolo della vita e della morte, accompagnati dai flautini e dalle percussioni, è quello più sincero e commovente.

Il Caprice per clarinetto e piano 335a risale al 1953 ed è stato pubblicato l’anno successivo: anche questo è un brano di breve durata e dalla semplice struttura (ABA), ma ancora una volta l’arte di Milhaud si esprime con la sua straordinaria abilità a modificare le simmetrie ritmiche e melodiche della composizione spostandole in modo quasi impercettibile: così, e a dispetto dell’apparente banalità dei materiali tematici utilizzati, il risultato finale è quello di suscitare un grande interesse nell’ascoltatore senza spostarlo troppo dalla propria area di confort.

La Sonatina Op.100 risale al 1927: anche in questo caso il titolo può risultare ingannevole, la tradizione delle Sonatine francesi nel primo novecento non è certo paragonabile a quella delle composizioni dell’epoca tardo galante e classica.

Anche dal punto di vista tecnico esecutivo la composizione non si presenta come di facile esecuzione: le sovrapposizioni armoniche e la poliritmia che caratterizzano i due movimenti estremi e la cupa cantabilità del movimento centrale richiedono una grande accuratezza esecutiva e una capacità di giocare con nonchalance con le spigolose dissonanze abbondantemente presenti nella partitura.

Gli ultimi anni della vita di Milhaud non furono agevoli: l’artrite che lo perseguitava lo aveva costretto alla sedia a rotelle ma, ciononostante, la sua attività di compositore, direttore d’orchestra e didatta non fu interrotta.

Molte delle composizione dell’ultimo periodo, tra cui il Duo concertante per clarinetto e piano Op.351 del 1956 (scritto, come Le Merle Noir di Olivier Messiaen come prova per il concorso di ammissione al Conservatorio di Parigi), comunicano un forte e gioioso desiderio di giocare con i suoni: in questo senso è possibile affermare che Milhaud è stato un compositore totalmente impermeabile alle tendenze tardo romantiche.

Pierluigi Bernard received his Master Degree in Music and Clarinet Performance at the G.Verdi Conservatory in his native city of Turin. He later went to the Guildhall School of Music & Drama in London where he studied under the great British master, the late Jack Brymer (O.B.E.). As Brymer’s disciple, Bernard received two of the former LSO Principal’s Boosey & Hawkes 1010 clarinets as a gift. He has also had the privilege of being the pupil of another outstanding clarinet player: Thomas Friedli. Mr. Bernard learned the secrets of chamber music directly from three living legends at the International Chamber Music Academy (founded by the Trio di Trieste in Duino) where he was placed as winner and finalist in various international and national competitions. Pierluigi has been a member of the European Community Youth Orchestra, soloist of the Guildhall Wind

Ensemble, member of the Orchestra del Teatro Regio in Turin, the Turin Philarmonic Orchestra, and Co-Soloist (from 1994-2011) and Soloist (from 2011 onwards) of the Tenerife Symphony Orchestra. He is a co-founding member of the Ensemble Laboratorio in Italy and founding member of the recently formed Tenerife Music Ensemble. He has held teaching positions at the Academy of Orchestral Studies of the Tenerife Symphony Orchestra and at Tenerife’s Music Conservatory. He is regularly invited to perform at various prestigious concert societies and has been member of the jury in different occasions at international and national competitions. As soloist has performed many times with the Tenerife Symphony Orchestra and in duo with

sua musica, questi potrebbero essere riassunti in questo modo: se la libertà consiste essenzialmente nella possibilità di assumersi la responsabilità della scelta, così l’ascoltatore può e deve assumersi la responsabilità di attribuire significato a ciò che ascolta e il compositore deve assumersi la responsabilità di permetterlo.A cura di Francesco Maschio

Mauro Tortorelli is considered by critics to be a virtuoso violinist of rare musical instinct and great interpretative skill. He studied violin with J.J.Kantorow, B.Belkin, F.Gulli and G.Mönch. In 1990, while still very young, he made his debut at the Teatro alla Scala in Milan playing a piece for two violins composed by Luigi Nono alongside his teacher G.Mönch. He works closely with artists of international standing such as F. Maggio Ormezowski, Rohan De Saram, Francois Joel Thioller, Alexandra Gutu, Franco Petracchi, Alfonso Ghedin, Daishin Kashimoto. He held Master Class at the Tchaikovsky Conservatoire in Moscow, at the Aichi University (Japan) and in Dubai Conservatoire. He recorded for Tactus Label, Naxos, Brilliant, Camerata Tokyo, Nuova Era, Stradivarius.www.maurotortorelli.com

the Russian violist Sviatoslav Belonogov and more recently performed the Duetto Concertino with Giorgio Mandolesi. Pierluigi has recorded two CDs: one of Rossini’s Introduction, Theme, and Variations; and another of Piazzolla’s Prelude and Dance. He is currently principal clarinet of the Tenerife Symphony Orchestra. Since 1993 Pierluigi Bernard is a Peter Eaton brand artist, and plays with traditional English Peter Eaton Elite wide bore clarinets.

Angela Meluso began studying piano at age five and she graduated with honours at the Conservatory of Music “A. Vivaldi” of Alessandria under Giacomo Fuga. She won the eleventh edition of the “Premio Ghislieri” coming first in the piano section. She has attended specialization studies at the Accademia in Florence with Lazar Berman, at the Accademia Hipponiana of Reggio Calabria with Vincenzo Balzani and for chamber music with Mauro Tortorelli, Giacomo Fuga, E. Bagnoli, Trio di Trieste and Trio di Parma (DuinoAccademy). She works closely with musicians such as Guido Arbonelli, Loris Antiga (horn

player with the London Symphony Orchestra), and with the lead players of the Teatro San Carlo in Naples and “Santa Cecilia” in Rome. Considered by critics to be a pianist of great character, interpretative sensitivity and communicative skill, she is also the author of Solfeggianimando, a method for teaching music, published in 2008 by Edizioni Zaccara.

We would like to thank:Kike Perdomo for his technical advice

José Ambrosio GonzalesUniversidad de La Laguna – Sala Paraninfo where the CD was recorded

Vicerrectorado de Relaciones con la Sociedad

Recording: 1-2 November 2016, Sala Paraninfo, Universidad de La Laguna, Tenerife, SpainProducer, Musical supervision and Mastering: Giovanni CarusoCover: Mountains in the Provence, by Paul Cezannep & © 2017 Brilliant Classics