What's on 'dubai's hottest restaurants' wheeler's coverage feb 2013

Meyerhold's

description

Transcript of Meyerhold's

-

The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Drama Review: TDR.

http://www.jstor.org

Meyerhold's "D. E." Author(s): Llewellyn H. Hedgbeth Source: The Drama Review: TDR, Vol. 19, No. 2, Political Theatre Issue (Jun., 1975), pp. 23-36Published by: The MIT PressStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1144943Accessed: 10-03-2015 17:19 UTC

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

This content downloaded from 160.80.178.241 on Tue, 10 Mar 2015 17:19:50 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

This content downloaded from 160.80.178.241 on Tue, 10 Mar 2015 17:19:50 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

LLEWELLEN H. HEDGBETH LLEWELLEN H. HEDGBETH LLEWELLEN H. HEDGBETH

Theatre. Based primarily on Ilya Ehrenburg's novel, Trust D.E., it also drew heavily on Bernard Kellermann's The Tunnels and touched upon novels by Pierre Hamp and Upton Sinclair.

A 1927 program offers a synopsis of the play, as well as the order of the episodes. Two world powers, the falling bourgeoisie and the rising proletariat, are juxtaposed in short theatrical sketches. Three American millionaires-Jubs, Twist, and Hardayle, who are in search of new markets-accept a proposal by Jens Boot, an international adven- turer, to form "D.E.," an organization whose aim is to destroy Europe, without boy- cotting American products or disseminating Socialistic ideas. Their ultimate goal is to claim Europe as an American colony. When this plot is discovered, the Soviet Comintern creates Radio Trust U.S.S.R. and calls on the proletariat of the Soviet Union and the displaced Westerners fleeing their fallen countries to work together. Secretly, they arrange to build a transatlantic tunnel, joining Leningrad with New York. It is through this tunnel that the International Red Army is to travel to America. While the work continues, D.E. destroys Germany, Austria, Hungary, and Scandinavia, changes France into a desert, and brings the English to cannibalism, but it cannot subdue the Soviet Union. The Russian workers are too strong to allow D.E. to conquer. The organizers of D.E. are forced to abandon their attempt to conquer the Soviet Union through eco- nomic means and annex it as a colony. Once the tunnel is completed, the American proletariat stages a spontaneous uprising, which is aided by the International Red Army, and captures D.E. The International Proletariat is victorious.

The novels merged for this play had varying literary styles and were difficult to piece together. Students of the Higher Military Pedagogical Institute made suggestions to Mikhail Podgaretsky, who compiled the original text. Then, Meyerhold's National Theatrical Workshop made comments and reworked the scenario. Throughout its run, the play was often revised because of the reaction and suggestions of spectators.

Ehrenburg, from the beginning, was not pleased with Meyerhold's notion of adapting Trust D.E. into a stage play. But Meyerhold had clear ideas about the pro- duction and was determined that he alone could do it justice. In his memoirs, Ehrenburg detailed their argument:

In the summer of 1923, I was living in Berlin. Meyerhold arrived, and we met. He suggested that I should adapt my Novel Trust D.E. for his theatre, saying that the play should be a mixture of a circus and a propaganda pageant. I did not feel like adapting the novel; I was beginning to lose my enthusiasm both for the circus and for Constructivism; had a passion for Dickens just then; and was writing a sentimental novel with a com- plicated plot, The Love of Jeanne Ney. I knew, however, that it was difficult to oppose Meyerhold and said that I would think about it. Shortly after that an article appeared in a theatrical journal published by Meyerhold's supporters. This article, which took the form of a fantasy tale, described how I had been 'stolen' by Tairov, for whom I had undertaken to turn my novel into a counter-revolutionary play. (Many times in his life Meyerhold suspected Tairov, that kindest and purest of men, of a desire to destroy him by no matter what means. It was part of that suspiciousness that I have already mentioned. Tairov never had the slightest intention of putting on Trust D.E.) Returning to the Soviet Union I read that Meyerhold was preparing to stage a play called Trust D.E. adapted by a certain Podgaretsky 'from

Theatre. Based primarily on Ilya Ehrenburg's novel, Trust D.E., it also drew heavily on Bernard Kellermann's The Tunnels and touched upon novels by Pierre Hamp and Upton Sinclair.

A 1927 program offers a synopsis of the play, as well as the order of the episodes. Two world powers, the falling bourgeoisie and the rising proletariat, are juxtaposed in short theatrical sketches. Three American millionaires-Jubs, Twist, and Hardayle, who are in search of new markets-accept a proposal by Jens Boot, an international adven- turer, to form "D.E.," an organization whose aim is to destroy Europe, without boy- cotting American products or disseminating Socialistic ideas. Their ultimate goal is to claim Europe as an American colony. When this plot is discovered, the Soviet Comintern creates Radio Trust U.S.S.R. and calls on the proletariat of the Soviet Union and the displaced Westerners fleeing their fallen countries to work together. Secretly, they arrange to build a transatlantic tunnel, joining Leningrad with New York. It is through this tunnel that the International Red Army is to travel to America. While the work continues, D.E. destroys Germany, Austria, Hungary, and Scandinavia, changes France into a desert, and brings the English to cannibalism, but it cannot subdue the Soviet Union. The Russian workers are too strong to allow D.E. to conquer. The organizers of D.E. are forced to abandon their attempt to conquer the Soviet Union through eco- nomic means and annex it as a colony. Once the tunnel is completed, the American proletariat stages a spontaneous uprising, which is aided by the International Red Army, and captures D.E. The International Proletariat is victorious.

The novels merged for this play had varying literary styles and were difficult to piece together. Students of the Higher Military Pedagogical Institute made suggestions to Mikhail Podgaretsky, who compiled the original text. Then, Meyerhold's National Theatrical Workshop made comments and reworked the scenario. Throughout its run, the play was often revised because of the reaction and suggestions of spectators.

Ehrenburg, from the beginning, was not pleased with Meyerhold's notion of adapting Trust D.E. into a stage play. But Meyerhold had clear ideas about the pro- duction and was determined that he alone could do it justice. In his memoirs, Ehrenburg detailed their argument:

In the summer of 1923, I was living in Berlin. Meyerhold arrived, and we met. He suggested that I should adapt my Novel Trust D.E. for his theatre, saying that the play should be a mixture of a circus and a propaganda pageant. I did not feel like adapting the novel; I was beginning to lose my enthusiasm both for the circus and for Constructivism; had a passion for Dickens just then; and was writing a sentimental novel with a com- plicated plot, The Love of Jeanne Ney. I knew, however, that it was difficult to oppose Meyerhold and said that I would think about it. Shortly after that an article appeared in a theatrical journal published by Meyerhold's supporters. This article, which took the form of a fantasy tale, described how I had been 'stolen' by Tairov, for whom I had undertaken to turn my novel into a counter-revolutionary play. (Many times in his life Meyerhold suspected Tairov, that kindest and purest of men, of a desire to destroy him by no matter what means. It was part of that suspiciousness that I have already mentioned. Tairov never had the slightest intention of putting on Trust D.E.) Returning to the Soviet Union I read that Meyerhold was preparing to stage a play called Trust D.E. adapted by a certain Podgaretsky 'from

Theatre. Based primarily on Ilya Ehrenburg's novel, Trust D.E., it also drew heavily on Bernard Kellermann's The Tunnels and touched upon novels by Pierre Hamp and Upton Sinclair.

A 1927 program offers a synopsis of the play, as well as the order of the episodes. Two world powers, the falling bourgeoisie and the rising proletariat, are juxtaposed in short theatrical sketches. Three American millionaires-Jubs, Twist, and Hardayle, who are in search of new markets-accept a proposal by Jens Boot, an international adven- turer, to form "D.E.," an organization whose aim is to destroy Europe, without boy- cotting American products or disseminating Socialistic ideas. Their ultimate goal is to claim Europe as an American colony. When this plot is discovered, the Soviet Comintern creates Radio Trust U.S.S.R. and calls on the proletariat of the Soviet Union and the displaced Westerners fleeing their fallen countries to work together. Secretly, they arrange to build a transatlantic tunnel, joining Leningrad with New York. It is through this tunnel that the International Red Army is to travel to America. While the work continues, D.E. destroys Germany, Austria, Hungary, and Scandinavia, changes France into a desert, and brings the English to cannibalism, but it cannot subdue the Soviet Union. The Russian workers are too strong to allow D.E. to conquer. The organizers of D.E. are forced to abandon their attempt to conquer the Soviet Union through eco- nomic means and annex it as a colony. Once the tunnel is completed, the American proletariat stages a spontaneous uprising, which is aided by the International Red Army, and captures D.E. The International Proletariat is victorious.

The novels merged for this play had varying literary styles and were difficult to piece together. Students of the Higher Military Pedagogical Institute made suggestions to Mikhail Podgaretsky, who compiled the original text. Then, Meyerhold's National Theatrical Workshop made comments and reworked the scenario. Throughout its run, the play was often revised because of the reaction and suggestions of spectators.

Ehrenburg, from the beginning, was not pleased with Meyerhold's notion of adapting Trust D.E. into a stage play. But Meyerhold had clear ideas about the pro- duction and was determined that he alone could do it justice. In his memoirs, Ehrenburg detailed their argument:

In the summer of 1923, I was living in Berlin. Meyerhold arrived, and we met. He suggested that I should adapt my Novel Trust D.E. for his theatre, saying that the play should be a mixture of a circus and a propaganda pageant. I did not feel like adapting the novel; I was beginning to lose my enthusiasm both for the circus and for Constructivism; had a passion for Dickens just then; and was writing a sentimental novel with a com- plicated plot, The Love of Jeanne Ney. I knew, however, that it was difficult to oppose Meyerhold and said that I would think about it. Shortly after that an article appeared in a theatrical journal published by Meyerhold's supporters. This article, which took the form of a fantasy tale, described how I had been 'stolen' by Tairov, for whom I had undertaken to turn my novel into a counter-revolutionary play. (Many times in his life Meyerhold suspected Tairov, that kindest and purest of men, of a desire to destroy him by no matter what means. It was part of that suspiciousness that I have already mentioned. Tairov never had the slightest intention of putting on Trust D.E.) Returning to the Soviet Union I read that Meyerhold was preparing to stage a play called Trust D.E. adapted by a certain Podgaretsky 'from

24 24 24

This content downloaded from 160.80.178.241 on Tue, 10 Mar 2015 17:19:50 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

MEYERHOLD'S D.E. MEYERHOLD'S D.E. MEYERHOLD'S D.E.

novels by Ehrenburg and Kellermann, I realized that the only argument which might stop Meyerhold would be for me to say that I wanted to adapt the novel myself for the theatre or the cinema. In March 1924, I wrote him a letter beginning 'Dear Vsevolod Emilyevich' and ending 'with heartfelt greetings': 'Our meeting last summer, and in particular our talks about the possibility of my adapting Trust D.E., allow me to believe that your attitude to my work is one of friendship and esteem. I therefore venture, first of all, to ask you-if the newspaper report is correct-to give up the idea of this production. After all, I am not a classic but a living man.' The reply was terrifying-it contained all the frenzy of which Meyerhold was capable-I should never mention it if I did not love the man with all his extremes. 'Citizen I. Ehrenburg! I fail to understand on what grounds you address a request to me to 'give up the idea' of producing Comrade Podgaretsky's play. Is it on the grounds of our talk in Berlin? Surely that talk made it clear enough that even if you were to undertake an adapta- tion of your novel, you would turn it into a play that could well be staged in any of the cities of the Entente.... in my theatre, which serves and will continue to serve the cause of the Revolution, we need tenden- tious plays, plays with one aim only: to serve the cause of the Revolu- tion. '

There is some discrepancy about whether or not Ehrenburg ever saw the produc- tion. Yelagin stated that Ehrenburg forced a change of costumes and make-up several times before the show opened, but Ehrenburg claimed never to have seen the play.

I did not go to see the play; according to friends' reports and articles by critics who supported Meyerhold, Podgaretsky made a poor job of it. The production was interesting. Europe perished amidst a great deal of noise, the panels of the set were hustled off the stage, the actors changed their make-up in a hurry, and a jazz band played deafeningly. To my surprise Mayakovsky stood up for me: at a debate on the production of Trust D.E. he said of the adaptation: 'The play D.E. is an absolute zero ... Only a man who stands on a higher level than the authors-in this case Ehrenburg and Kellermann-can adapt a work of fiction for the stage.' However, the production enjoyed some success, and the Java tobacco factory issued a brand of cigarettes called D.E. But as a result of this silly business I did not meet Meyerhold again for seven years.

SCENIC ELEMENTS

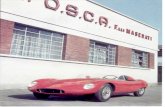

The set is probably the single most important element in this production. Meyer- hold had been thinking for some time in terms of outdoor performances, and Craig's 1909 experiments with screens may well have influenced him to adopt the use of moving walls. In use were eight to ten flat wooden screens twelve feet long and nine feet high, as well as several screens of smaller dimensions, moved on small wheels by stage- hands behind each one. These walls were made of a special wood used for freight cars and were painted a dark red brick color. Ilya Shlepyanov executed the walls, whose position could be changed rapidly to totally alter the background. A lecture hall was

novels by Ehrenburg and Kellermann, I realized that the only argument which might stop Meyerhold would be for me to say that I wanted to adapt the novel myself for the theatre or the cinema. In March 1924, I wrote him a letter beginning 'Dear Vsevolod Emilyevich' and ending 'with heartfelt greetings': 'Our meeting last summer, and in particular our talks about the possibility of my adapting Trust D.E., allow me to believe that your attitude to my work is one of friendship and esteem. I therefore venture, first of all, to ask you-if the newspaper report is correct-to give up the idea of this production. After all, I am not a classic but a living man.' The reply was terrifying-it contained all the frenzy of which Meyerhold was capable-I should never mention it if I did not love the man with all his extremes. 'Citizen I. Ehrenburg! I fail to understand on what grounds you address a request to me to 'give up the idea' of producing Comrade Podgaretsky's play. Is it on the grounds of our talk in Berlin? Surely that talk made it clear enough that even if you were to undertake an adapta- tion of your novel, you would turn it into a play that could well be staged in any of the cities of the Entente.... in my theatre, which serves and will continue to serve the cause of the Revolution, we need tenden- tious plays, plays with one aim only: to serve the cause of the Revolu- tion. '

There is some discrepancy about whether or not Ehrenburg ever saw the produc- tion. Yelagin stated that Ehrenburg forced a change of costumes and make-up several times before the show opened, but Ehrenburg claimed never to have seen the play.

I did not go to see the play; according to friends' reports and articles by critics who supported Meyerhold, Podgaretsky made a poor job of it. The production was interesting. Europe perished amidst a great deal of noise, the panels of the set were hustled off the stage, the actors changed their make-up in a hurry, and a jazz band played deafeningly. To my surprise Mayakovsky stood up for me: at a debate on the production of Trust D.E. he said of the adaptation: 'The play D.E. is an absolute zero ... Only a man who stands on a higher level than the authors-in this case Ehrenburg and Kellermann-can adapt a work of fiction for the stage.' However, the production enjoyed some success, and the Java tobacco factory issued a brand of cigarettes called D.E. But as a result of this silly business I did not meet Meyerhold again for seven years.

SCENIC ELEMENTS

The set is probably the single most important element in this production. Meyer- hold had been thinking for some time in terms of outdoor performances, and Craig's 1909 experiments with screens may well have influenced him to adopt the use of moving walls. In use were eight to ten flat wooden screens twelve feet long and nine feet high, as well as several screens of smaller dimensions, moved on small wheels by stage- hands behind each one. These walls were made of a special wood used for freight cars and were painted a dark red brick color. Ilya Shlepyanov executed the walls, whose position could be changed rapidly to totally alter the background. A lecture hall was

novels by Ehrenburg and Kellermann, I realized that the only argument which might stop Meyerhold would be for me to say that I wanted to adapt the novel myself for the theatre or the cinema. In March 1924, I wrote him a letter beginning 'Dear Vsevolod Emilyevich' and ending 'with heartfelt greetings': 'Our meeting last summer, and in particular our talks about the possibility of my adapting Trust D.E., allow me to believe that your attitude to my work is one of friendship and esteem. I therefore venture, first of all, to ask you-if the newspaper report is correct-to give up the idea of this production. After all, I am not a classic but a living man.' The reply was terrifying-it contained all the frenzy of which Meyerhold was capable-I should never mention it if I did not love the man with all his extremes. 'Citizen I. Ehrenburg! I fail to understand on what grounds you address a request to me to 'give up the idea' of producing Comrade Podgaretsky's play. Is it on the grounds of our talk in Berlin? Surely that talk made it clear enough that even if you were to undertake an adapta- tion of your novel, you would turn it into a play that could well be staged in any of the cities of the Entente.... in my theatre, which serves and will continue to serve the cause of the Revolution, we need tenden- tious plays, plays with one aim only: to serve the cause of the Revolu- tion. '

There is some discrepancy about whether or not Ehrenburg ever saw the produc- tion. Yelagin stated that Ehrenburg forced a change of costumes and make-up several times before the show opened, but Ehrenburg claimed never to have seen the play.

I did not go to see the play; according to friends' reports and articles by critics who supported Meyerhold, Podgaretsky made a poor job of it. The production was interesting. Europe perished amidst a great deal of noise, the panels of the set were hustled off the stage, the actors changed their make-up in a hurry, and a jazz band played deafeningly. To my surprise Mayakovsky stood up for me: at a debate on the production of Trust D.E. he said of the adaptation: 'The play D.E. is an absolute zero ... Only a man who stands on a higher level than the authors-in this case Ehrenburg and Kellermann-can adapt a work of fiction for the stage.' However, the production enjoyed some success, and the Java tobacco factory issued a brand of cigarettes called D.E. But as a result of this silly business I did not meet Meyerhold again for seven years.

SCENIC ELEMENTS

The set is probably the single most important element in this production. Meyer- hold had been thinking for some time in terms of outdoor performances, and Craig's 1909 experiments with screens may well have influenced him to adopt the use of moving walls. In use were eight to ten flat wooden screens twelve feet long and nine feet high, as well as several screens of smaller dimensions, moved on small wheels by stage- hands behind each one. These walls were made of a special wood used for freight cars and were painted a dark red brick color. Ilya Shlepyanov executed the walls, whose position could be changed rapidly to totally alter the background. A lecture hall was

25 25 25

This content downloaded from 160.80.178.241 on Tue, 10 Mar 2015 17:19:50 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

The moveable walls for D.E., 1924. The moveable walls for D.E., 1924. The moveable walls for D.E., 1924.

quickly transformed into a street with an endless fence, the street became a chamber of Parliament, the Parliament hall changed within a few seconds into a stadium. These changes were often effected by the addition of some simple object, like a lantern, or a poster, as well as by the actual change in configuration.

In addition to the moveable walls, Meyerhold used a series of screens. A standing screen was used for projections during some scenes, but Meyerhold employed three screens-one large center screen and two smaller side screens flown in and out of the flies-for most of the episodes. The titles of the episodes, the location and characters involved in each episode, and the attitudes of the director toward the onstage action were projected on the large center screen. The side screens were used to communicate information about the two opposing forces, such as the political appeals of the "Asso- ciation for Chemical Defense," catchwords of Communist propaganda, portraits of party leaders, and quotations from Lenin's and Zinoviev's speeches and writings. The propaganda was straightforward: "Hands Off China!," "White Immigrants!," appearing after pictures had been projected of the enemy forces and maps of faltering Europe.

General stage lighting was accomplished by instruments hung at the rear of the auditorium and special lighting came from projectorsthung both at the rear of the auditorium and at the side of the stage. Rather than being used to create specific colors or moods, the lighting became a more functional part of the show. At times, flickering lights and weaving beams of light produced an intense dynamism of action as movement changed from one part of the stage to another, or from episode to episode. Many characters were dressed in an' exaggerated manner-fright wigs, large shoes, floppy bow tie, pork-pie hat-more reminiscent of clowns than of actors. With other characters, entire scenes were built about bright colorful costumes that gave attention to fine details. Only the stagehands were in the traditional Meyerhold costumes of blue-flared pants and blue shirts made from a light material.

ACTING STYLES Each episode had some connection with the central theme of the play. However,

only two or three scenes were tied together by the same heroes. Each episode had its own acting style. The result of this was a jerkiness established as each scene broke off

quickly transformed into a street with an endless fence, the street became a chamber of Parliament, the Parliament hall changed within a few seconds into a stadium. These changes were often effected by the addition of some simple object, like a lantern, or a poster, as well as by the actual change in configuration.

In addition to the moveable walls, Meyerhold used a series of screens. A standing screen was used for projections during some scenes, but Meyerhold employed three screens-one large center screen and two smaller side screens flown in and out of the flies-for most of the episodes. The titles of the episodes, the location and characters involved in each episode, and the attitudes of the director toward the onstage action were projected on the large center screen. The side screens were used to communicate information about the two opposing forces, such as the political appeals of the "Asso- ciation for Chemical Defense," catchwords of Communist propaganda, portraits of party leaders, and quotations from Lenin's and Zinoviev's speeches and writings. The propaganda was straightforward: "Hands Off China!," "White Immigrants!," appearing after pictures had been projected of the enemy forces and maps of faltering Europe.

General stage lighting was accomplished by instruments hung at the rear of the auditorium and special lighting came from projectorsthung both at the rear of the auditorium and at the side of the stage. Rather than being used to create specific colors or moods, the lighting became a more functional part of the show. At times, flickering lights and weaving beams of light produced an intense dynamism of action as movement changed from one part of the stage to another, or from episode to episode. Many characters were dressed in an' exaggerated manner-fright wigs, large shoes, floppy bow tie, pork-pie hat-more reminiscent of clowns than of actors. With other characters, entire scenes were built about bright colorful costumes that gave attention to fine details. Only the stagehands were in the traditional Meyerhold costumes of blue-flared pants and blue shirts made from a light material.

ACTING STYLES Each episode had some connection with the central theme of the play. However,

only two or three scenes were tied together by the same heroes. Each episode had its own acting style. The result of this was a jerkiness established as each scene broke off

quickly transformed into a street with an endless fence, the street became a chamber of Parliament, the Parliament hall changed within a few seconds into a stadium. These changes were often effected by the addition of some simple object, like a lantern, or a poster, as well as by the actual change in configuration.

In addition to the moveable walls, Meyerhold used a series of screens. A standing screen was used for projections during some scenes, but Meyerhold employed three screens-one large center screen and two smaller side screens flown in and out of the flies-for most of the episodes. The titles of the episodes, the location and characters involved in each episode, and the attitudes of the director toward the onstage action were projected on the large center screen. The side screens were used to communicate information about the two opposing forces, such as the political appeals of the "Asso- ciation for Chemical Defense," catchwords of Communist propaganda, portraits of party leaders, and quotations from Lenin's and Zinoviev's speeches and writings. The propaganda was straightforward: "Hands Off China!," "White Immigrants!," appearing after pictures had been projected of the enemy forces and maps of faltering Europe.

General stage lighting was accomplished by instruments hung at the rear of the auditorium and special lighting came from projectorsthung both at the rear of the auditorium and at the side of the stage. Rather than being used to create specific colors or moods, the lighting became a more functional part of the show. At times, flickering lights and weaving beams of light produced an intense dynamism of action as movement changed from one part of the stage to another, or from episode to episode. Many characters were dressed in an' exaggerated manner-fright wigs, large shoes, floppy bow tie, pork-pie hat-more reminiscent of clowns than of actors. With other characters, entire scenes were built about bright colorful costumes that gave attention to fine details. Only the stagehands were in the traditional Meyerhold costumes of blue-flared pants and blue shirts made from a light material.

ACTING STYLES Each episode had some connection with the central theme of the play. However,

only two or three scenes were tied together by the same heroes. Each episode had its own acting style. The result of this was a jerkiness established as each scene broke off

This content downloaded from 160.80.178.241 on Tue, 10 Mar 2015 17:19:50 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

MEYERHOLD'S D.E. MEYERHOLD'S D.E. MEYERHOLD'S D.E.

and was transformed into a new place with new people. Parades of actual Soviet mari- ners and athletes were contrasted with the scenes of moral dissolution in Europe. Meyerhold portrayed the European scene in a satirical and sometimes farcical manner, but the audiences obviously enjoyed the dancing girls and the beautifully dressed ladies from the West.

Whether or not he was successful, Meyerhold hoped that, when shown enter- tainments copied from popular Western theatre as only a small part of the agit-prop spectacle, the audience would acknowledge the superiority of Soviet theatre. This theatre could match the achievements of the West and add its own theatricalism as well. Difference of tempo was essential to this comparison. While the decadent bourgeois representatives danced indolently in the nightclub, the Russians, the hope of the future, did brisk biomechanical exercises. Boris Alpers claimed that "those belonging to the bourgeois world were treated in the manner of sharp social grotesque-the theatre of masks; the Soviet personages-people of the Socialist world-were played simply and naturally, strictly according to real life."

In D.E. there were ninety-five roles for forty-five performers. Meyerhold's major production problem was the transformiation of the actor. One actor playing many roles had been often used to hide the fact that there were too few actors, but Meyerhold used it on a large scale here, declaring it on the posters that announced the play's opening. He hoped the audience would be able to look at the artistic talent of the actor and to recognize the irony involved in the same men playing roles involved with two opposing forces. Tovaritch Bogooshevski suggested that the episodic transformations be presented as dreams. This suggestion was adopted. Several actors ran behind the walls to change into new costumes and reappeared at once as quite different characters.

Detailed pantomime also came to the fore in this production, even more than in Meyerhold's earlier efforts. There were several episodes that lasted ten to fifteen minutes and contained an insignificant amount of speech but a lot of pantomime.

There was an actor's chase in D.E. in which a fugitive fled, was hemmed in by moving walls, disappeared behind one of them, and was spirited offstage. As the actor began to run, the spotlights rushed about, and all the walls began to move in different directions, creating a dynamic picture.

Garin, Zakhava, and Okhlopkov were three of the most notable actors involved in the review. Erast Garin was the Great Transformer who, within one fifteen-minute scene, performed seven different roles. At one point, Meyerhold had a peephole made in one of the walls and, as old-time vaudeville music was played, the audience watched Garin's changes and viewed his character ironically, as an artifically created person.

Boris Zakhava, now the head of the Vakhtangov Theatre School, played an English lord and a French parliamentarian in D.E. When he first read the play, he did not like it and told Meyerhold so. Meyerhold released him from one part, but he still played a large role as the Chairman of the French Parliament. Zakhava felt confident in this role, and the gestures came to him easily. In this role, he rang a large bell for the Fascist deputies and a small bell for the Communist deputies. They expressed the feelings of the chair- man toward the political groups. But Zakhava was uncomfortable using them. He felt the bells were actors playing his part. In his view, the actor hardly seemed necessary. (Zakhava later wrote: "I am capable of expressing satirical theatre more brightly and fully than the very best marionette with ten bells." When he was certain that the audience accepted him, he decided on an experiment. In one performance, when Meyer- hold was not present, Zakhava hid the large bell behind the podium and worked with only one bell. The audience accepted this innovation. When Meyerhold saw it, he accepted it, too.)

and was transformed into a new place with new people. Parades of actual Soviet mari- ners and athletes were contrasted with the scenes of moral dissolution in Europe. Meyerhold portrayed the European scene in a satirical and sometimes farcical manner, but the audiences obviously enjoyed the dancing girls and the beautifully dressed ladies from the West.

Whether or not he was successful, Meyerhold hoped that, when shown enter- tainments copied from popular Western theatre as only a small part of the agit-prop spectacle, the audience would acknowledge the superiority of Soviet theatre. This theatre could match the achievements of the West and add its own theatricalism as well. Difference of tempo was essential to this comparison. While the decadent bourgeois representatives danced indolently in the nightclub, the Russians, the hope of the future, did brisk biomechanical exercises. Boris Alpers claimed that "those belonging to the bourgeois world were treated in the manner of sharp social grotesque-the theatre of masks; the Soviet personages-people of the Socialist world-were played simply and naturally, strictly according to real life."

In D.E. there were ninety-five roles for forty-five performers. Meyerhold's major production problem was the transformiation of the actor. One actor playing many roles had been often used to hide the fact that there were too few actors, but Meyerhold used it on a large scale here, declaring it on the posters that announced the play's opening. He hoped the audience would be able to look at the artistic talent of the actor and to recognize the irony involved in the same men playing roles involved with two opposing forces. Tovaritch Bogooshevski suggested that the episodic transformations be presented as dreams. This suggestion was adopted. Several actors ran behind the walls to change into new costumes and reappeared at once as quite different characters.

Detailed pantomime also came to the fore in this production, even more than in Meyerhold's earlier efforts. There were several episodes that lasted ten to fifteen minutes and contained an insignificant amount of speech but a lot of pantomime.

There was an actor's chase in D.E. in which a fugitive fled, was hemmed in by moving walls, disappeared behind one of them, and was spirited offstage. As the actor began to run, the spotlights rushed about, and all the walls began to move in different directions, creating a dynamic picture.

Garin, Zakhava, and Okhlopkov were three of the most notable actors involved in the review. Erast Garin was the Great Transformer who, within one fifteen-minute scene, performed seven different roles. At one point, Meyerhold had a peephole made in one of the walls and, as old-time vaudeville music was played, the audience watched Garin's changes and viewed his character ironically, as an artifically created person.

Boris Zakhava, now the head of the Vakhtangov Theatre School, played an English lord and a French parliamentarian in D.E. When he first read the play, he did not like it and told Meyerhold so. Meyerhold released him from one part, but he still played a large role as the Chairman of the French Parliament. Zakhava felt confident in this role, and the gestures came to him easily. In this role, he rang a large bell for the Fascist deputies and a small bell for the Communist deputies. They expressed the feelings of the chair- man toward the political groups. But Zakhava was uncomfortable using them. He felt the bells were actors playing his part. In his view, the actor hardly seemed necessary. (Zakhava later wrote: "I am capable of expressing satirical theatre more brightly and fully than the very best marionette with ten bells." When he was certain that the audience accepted him, he decided on an experiment. In one performance, when Meyer- hold was not present, Zakhava hid the large bell behind the podium and worked with only one bell. The audience accepted this innovation. When Meyerhold saw it, he accepted it, too.)

and was transformed into a new place with new people. Parades of actual Soviet mari- ners and athletes were contrasted with the scenes of moral dissolution in Europe. Meyerhold portrayed the European scene in a satirical and sometimes farcical manner, but the audiences obviously enjoyed the dancing girls and the beautifully dressed ladies from the West.

Whether or not he was successful, Meyerhold hoped that, when shown enter- tainments copied from popular Western theatre as only a small part of the agit-prop spectacle, the audience would acknowledge the superiority of Soviet theatre. This theatre could match the achievements of the West and add its own theatricalism as well. Difference of tempo was essential to this comparison. While the decadent bourgeois representatives danced indolently in the nightclub, the Russians, the hope of the future, did brisk biomechanical exercises. Boris Alpers claimed that "those belonging to the bourgeois world were treated in the manner of sharp social grotesque-the theatre of masks; the Soviet personages-people of the Socialist world-were played simply and naturally, strictly according to real life."

In D.E. there were ninety-five roles for forty-five performers. Meyerhold's major production problem was the transformiation of the actor. One actor playing many roles had been often used to hide the fact that there were too few actors, but Meyerhold used it on a large scale here, declaring it on the posters that announced the play's opening. He hoped the audience would be able to look at the artistic talent of the actor and to recognize the irony involved in the same men playing roles involved with two opposing forces. Tovaritch Bogooshevski suggested that the episodic transformations be presented as dreams. This suggestion was adopted. Several actors ran behind the walls to change into new costumes and reappeared at once as quite different characters.

Detailed pantomime also came to the fore in this production, even more than in Meyerhold's earlier efforts. There were several episodes that lasted ten to fifteen minutes and contained an insignificant amount of speech but a lot of pantomime.

There was an actor's chase in D.E. in which a fugitive fled, was hemmed in by moving walls, disappeared behind one of them, and was spirited offstage. As the actor began to run, the spotlights rushed about, and all the walls began to move in different directions, creating a dynamic picture.

Garin, Zakhava, and Okhlopkov were three of the most notable actors involved in the review. Erast Garin was the Great Transformer who, within one fifteen-minute scene, performed seven different roles. At one point, Meyerhold had a peephole made in one of the walls and, as old-time vaudeville music was played, the audience watched Garin's changes and viewed his character ironically, as an artifically created person.

Boris Zakhava, now the head of the Vakhtangov Theatre School, played an English lord and a French parliamentarian in D.E. When he first read the play, he did not like it and told Meyerhold so. Meyerhold released him from one part, but he still played a large role as the Chairman of the French Parliament. Zakhava felt confident in this role, and the gestures came to him easily. In this role, he rang a large bell for the Fascist deputies and a small bell for the Communist deputies. They expressed the feelings of the chair- man toward the political groups. But Zakhava was uncomfortable using them. He felt the bells were actors playing his part. In his view, the actor hardly seemed necessary. (Zakhava later wrote: "I am capable of expressing satirical theatre more brightly and fully than the very best marionette with ten bells." When he was certain that the audience accepted him, he decided on an experiment. In one performance, when Meyer- hold was not present, Zakhava hid the large bell behind the podium and worked with only one bell. The audience accepted this innovation. When Meyerhold saw it, he accepted it, too.)

27 27 27

This content downloaded from 160.80.178.241 on Tue, 10 Mar 2015 17:19:50 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

LLEWELLYN H. HEDGBETH LLEWELLYN H. HEDGBETH LLEWELLYN H. HEDGBETH

The differing tempos set up in comparing the two political enemies in D.E. were carried out effectively in Okhlopkov's tempo acting. He emphasized varying rhythms within his own body, allowing his face, hands, legs, back, etc., to act independently. He talked very slowly, for example, as his foot tapped a quick rhythm. Slowing motion down, or speeding it up according to actual counted beats for each part of an action allowed him to make clear separations.

MUSIC AND DANCE The music in D.E. was illustrative and closely tied to the dramatic rhythm of the

piece. For instance, the music of a Western foxtrot was quickly contrasted with a march of the proletariat. An orchestra at times played bits and pieces of traditional sympho- nies or well-known songs such as "Boldly, Comrades" and the "Internationale," but a jazz band with saxophones, xylophones, pianos, violins, contra basses, bass and snare drums was the major attraction. The songs were popular hits-"My Baby," "Rose," "For I Love You Happy," "Clap Hands," "California," "Suez," "Chong," "Sandman," "For Me and My Gal," "Sphinks," [sic] "Monte-Carlo," "Sunflower," and "Indian Flower."

Everything European in the performance was parodied in time to jazz, new dance steps, or Capitalists madly conversing as they rocked in bentwood rockers. Europe was seen as a merry, magnificent farce, while the Soviet Union was depicted as a well- ordered land assured of final victory. Various tempos and rhythms, earlier explored in Biomechanics, led Meyerhold to the use of tempo acting, musical timing, etc., as he presented an ironical utopian sketch in which the lavish West enjoyed a languid life as destruction knocked at its door.

Meyerhold asked Sofia Parnok to organize the Soviet Union's first jazz band for the performance. Once the news of Parnok's leadership became known, good musicians were attracted to the band and Gabrilovitch and Kostomolotsky, men well known in the music field, sat among the players. The party critics objected to Parnok, who had just returned from Paris, and to his "degenerate" music, but the audiences loved it.

When Sidney Bechet and his jazz quintet visited the Soviet Union in 1925, he gave two concerts a day for several months to capacity houses. This was Moscow's first taste of genuine American jazz. The audiences went wild. They stamped their feet, shouted, and applauded in a frenzy. Meyerhold asked Bechet and his group to perform in D.E., and for some time the visitors to the Meyerhold Theatre were thrilled by the group's artistry. The passionate interest of Soviet citizens in jazz began here.

Ihe choreography was created by Kasyan Goleizovsky, Sofia Parnok, and Kos- tomolotsky. In the first episode, Parnok choreographed and performed while Kosto- molotsky directed the dance of "the floors of hieroglyphics" and the dance of the "giraffe-like stiff person." Goleizovsky, a member of FEKS, the Factory of the Eccen- tric Actor, choreographed the Biomechanical etudes and the acrobatic polka of episode six. In the seventh episode, he brought to the Soviet stage the foxtrot, tap dancing, the tango, and the shimmy. Kostomolotsky produced and performed his own eccentric dance in the same episode.

EPISODES The titles of the episodes were taken from the 1927 program. There was relatively

little description of the action within the episodes. Working from existing photographs and from written accounts, it has sometimes been possible to reconstruct a skeleton outline of the episode. More often, only a phrase, an important character or action, helps to identify the scene.

The differing tempos set up in comparing the two political enemies in D.E. were carried out effectively in Okhlopkov's tempo acting. He emphasized varying rhythms within his own body, allowing his face, hands, legs, back, etc., to act independently. He talked very slowly, for example, as his foot tapped a quick rhythm. Slowing motion down, or speeding it up according to actual counted beats for each part of an action allowed him to make clear separations.

MUSIC AND DANCE The music in D.E. was illustrative and closely tied to the dramatic rhythm of the

piece. For instance, the music of a Western foxtrot was quickly contrasted with a march of the proletariat. An orchestra at times played bits and pieces of traditional sympho- nies or well-known songs such as "Boldly, Comrades" and the "Internationale," but a jazz band with saxophones, xylophones, pianos, violins, contra basses, bass and snare drums was the major attraction. The songs were popular hits-"My Baby," "Rose," "For I Love You Happy," "Clap Hands," "California," "Suez," "Chong," "Sandman," "For Me and My Gal," "Sphinks," [sic] "Monte-Carlo," "Sunflower," and "Indian Flower."

Everything European in the performance was parodied in time to jazz, new dance steps, or Capitalists madly conversing as they rocked in bentwood rockers. Europe was seen as a merry, magnificent farce, while the Soviet Union was depicted as a well- ordered land assured of final victory. Various tempos and rhythms, earlier explored in Biomechanics, led Meyerhold to the use of tempo acting, musical timing, etc., as he presented an ironical utopian sketch in which the lavish West enjoyed a languid life as destruction knocked at its door.

Meyerhold asked Sofia Parnok to organize the Soviet Union's first jazz band for the performance. Once the news of Parnok's leadership became known, good musicians were attracted to the band and Gabrilovitch and Kostomolotsky, men well known in the music field, sat among the players. The party critics objected to Parnok, who had just returned from Paris, and to his "degenerate" music, but the audiences loved it.

When Sidney Bechet and his jazz quintet visited the Soviet Union in 1925, he gave two concerts a day for several months to capacity houses. This was Moscow's first taste of genuine American jazz. The audiences went wild. They stamped their feet, shouted, and applauded in a frenzy. Meyerhold asked Bechet and his group to perform in D.E., and for some time the visitors to the Meyerhold Theatre were thrilled by the group's artistry. The passionate interest of Soviet citizens in jazz began here.

Ihe choreography was created by Kasyan Goleizovsky, Sofia Parnok, and Kos- tomolotsky. In the first episode, Parnok choreographed and performed while Kosto- molotsky directed the dance of "the floors of hieroglyphics" and the dance of the "giraffe-like stiff person." Goleizovsky, a member of FEKS, the Factory of the Eccen- tric Actor, choreographed the Biomechanical etudes and the acrobatic polka of episode six. In the seventh episode, he brought to the Soviet stage the foxtrot, tap dancing, the tango, and the shimmy. Kostomolotsky produced and performed his own eccentric dance in the same episode.

EPISODES The titles of the episodes were taken from the 1927 program. There was relatively

little description of the action within the episodes. Working from existing photographs and from written accounts, it has sometimes been possible to reconstruct a skeleton outline of the episode. More often, only a phrase, an important character or action, helps to identify the scene.

The differing tempos set up in comparing the two political enemies in D.E. were carried out effectively in Okhlopkov's tempo acting. He emphasized varying rhythms within his own body, allowing his face, hands, legs, back, etc., to act independently. He talked very slowly, for example, as his foot tapped a quick rhythm. Slowing motion down, or speeding it up according to actual counted beats for each part of an action allowed him to make clear separations.

MUSIC AND DANCE The music in D.E. was illustrative and closely tied to the dramatic rhythm of the

piece. For instance, the music of a Western foxtrot was quickly contrasted with a march of the proletariat. An orchestra at times played bits and pieces of traditional sympho- nies or well-known songs such as "Boldly, Comrades" and the "Internationale," but a jazz band with saxophones, xylophones, pianos, violins, contra basses, bass and snare drums was the major attraction. The songs were popular hits-"My Baby," "Rose," "For I Love You Happy," "Clap Hands," "California," "Suez," "Chong," "Sandman," "For Me and My Gal," "Sphinks," [sic] "Monte-Carlo," "Sunflower," and "Indian Flower."

Everything European in the performance was parodied in time to jazz, new dance steps, or Capitalists madly conversing as they rocked in bentwood rockers. Europe was seen as a merry, magnificent farce, while the Soviet Union was depicted as a well- ordered land assured of final victory. Various tempos and rhythms, earlier explored in Biomechanics, led Meyerhold to the use of tempo acting, musical timing, etc., as he presented an ironical utopian sketch in which the lavish West enjoyed a languid life as destruction knocked at its door.

Meyerhold asked Sofia Parnok to organize the Soviet Union's first jazz band for the performance. Once the news of Parnok's leadership became known, good musicians were attracted to the band and Gabrilovitch and Kostomolotsky, men well known in the music field, sat among the players. The party critics objected to Parnok, who had just returned from Paris, and to his "degenerate" music, but the audiences loved it.

When Sidney Bechet and his jazz quintet visited the Soviet Union in 1925, he gave two concerts a day for several months to capacity houses. This was Moscow's first taste of genuine American jazz. The audiences went wild. They stamped their feet, shouted, and applauded in a frenzy. Meyerhold asked Bechet and his group to perform in D.E., and for some time the visitors to the Meyerhold Theatre were thrilled by the group's artistry. The passionate interest of Soviet citizens in jazz began here.

Ihe choreography was created by Kasyan Goleizovsky, Sofia Parnok, and Kos- tomolotsky. In the first episode, Parnok choreographed and performed while Kosto- molotsky directed the dance of "the floors of hieroglyphics" and the dance of the "giraffe-like stiff person." Goleizovsky, a member of FEKS, the Factory of the Eccen- tric Actor, choreographed the Biomechanical etudes and the acrobatic polka of episode six. In the seventh episode, he brought to the Soviet stage the foxtrot, tap dancing, the tango, and the shimmy. Kostomolotsky produced and performed his own eccentric dance in the same episode.

EPISODES The titles of the episodes were taken from the 1927 program. There was relatively

little description of the action within the episodes. Working from existing photographs and from written accounts, it has sometimes been possible to reconstruct a skeleton outline of the episode. More often, only a phrase, an important character or action, helps to identify the scene.

28 28 28

This content downloaded from 160.80.178.241 on Tue, 10 Mar 2015 17:19:50 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

MEYERHOLD'S D.E. MEYERHOLD'S D.E. MEYERHOLD'S D.E.

Act I-Episode l-"The Project of the Grandiose Ruination" This episode took the form of a lecture hall scene. In it, Garin played the roles of

seven different inventors. Though not identified as such, this scene may well be depicted by the picture of a circus-like fat man atop a circular platform backed by a comic caricature appearing on a standing screen. He held one statue and, with a pointer,

Act I-Episode l-"The Project of the Grandiose Ruination" This episode took the form of a lecture hall scene. In it, Garin played the roles of

seven different inventors. Though not identified as such, this scene may well be depicted by the picture of a circus-like fat man atop a circular platform backed by a comic caricature appearing on a standing screen. He held one statue and, with a pointer,

Act I-Episode l-"The Project of the Grandiose Ruination" This episode took the form of a lecture hall scene. In it, Garin played the roles of

seven different inventors. Though not identified as such, this scene may well be depicted by the picture of a circus-like fat man atop a circular platform backed by a comic caricature appearing on a standing screen. He held one statue and, with a pointer,

pointed to a second placed on a large circular podium beside him. A Charlie Chaplin figure, illustrative of Meyerhold's interest in mime and physical training, sat at the fat man's left, staring at a female statue.

With a hoarse, screaming voice, Garin plays the fifth inventor whose crippled leg-a character on to itself-inadvertently, kicks the millionaire interviewer. Eventually a kick lands the millionaire on the floor as his secretary writes in a slate, "No. 5, a scrapper."

Episode 2-"Multiply Wisely"

pointed to a second placed on a large circular podium beside him. A Charlie Chaplin figure, illustrative of Meyerhold's interest in mime and physical training, sat at the fat man's left, staring at a female statue.

With a hoarse, screaming voice, Garin plays the fifth inventor whose crippled leg-a character on to itself-inadvertently, kicks the millionaire interviewer. Eventually a kick lands the millionaire on the floor as his secretary writes in a slate, "No. 5, a scrapper."

Episode 2-"Multiply Wisely"

pointed to a second placed on a large circular podium beside him. A Charlie Chaplin figure, illustrative of Meyerhold's interest in mime and physical training, sat at the fat man's left, staring at a female statue.

With a hoarse, screaming voice, Garin plays the fifth inventor whose crippled leg-a character on to itself-inadvertently, kicks the millionaire interviewer. Eventually a kick lands the millionaire on the floor as his secretary writes in a slate, "No. 5, a scrapper."

Episode 2-"Multiply Wisely"

29 29 29

This content downloaded from 160.80.178.241 on Tue, 10 Mar 2015 17:19:50 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

LLEWELLYN H. HEDGBETH LLEWELLYN H. HEDGBETH LLEWELLYN H. HEDGBETH

Episode 3-"The Project of the Grandiose Construction" This episode, which was concerned with electricity being used for the first time in

the Soviet Union, was represented by a Moscow street scene. Four walls placed on their sides end-to-end created a straight diagonal across the stage and represented the street's fence. A swinging lamp was dropped in from the flies and was met by a post moved in from one side, thus creating a lamppost. A kiosk ten feet tall and about three feet in diameter came out from one of the wings. It was covered with signs and posters.

Episode 3-"The Project of the Grandiose Construction" This episode, which was concerned with electricity being used for the first time in

the Soviet Union, was represented by a Moscow street scene. Four walls placed on their sides end-to-end created a straight diagonal across the stage and represented the street's fence. A swinging lamp was dropped in from the flies and was met by a post moved in from one side, thus creating a lamppost. A kiosk ten feet tall and about three feet in diameter came out from one of the wings. It was covered with signs and posters.

Episode 3-"The Project of the Grandiose Construction" This episode, which was concerned with electricity being used for the first time in

the Soviet Union, was represented by a Moscow street scene. Four walls placed on their sides end-to-end created a straight diagonal across the stage and represented the street's fence. A swinging lamp was dropped in from the flies and was met by a post moved in from one side, thus creating a lamppost. A kiosk ten feet tall and about three feet in diameter came out from one of the wings. It was covered with signs and posters.

Episode 4-"Enough of Peace"

The French Parliament hall episode divided the deputies of Parliament into the place of the left and the place of the right. Eight large screens and one small one were used for this scene. Two walls stood on end next to each other and were furthest upstage; on either side of them were placed, a little further downstage, two walls on their sides. Another wall on its side led back from the vertical walls at about a 145? angle. In front of the two sets of walls on their sides were two smaller walls, both with side returns. The smallest of these created the chairman's podium. On the far sides of the stage were large lettered signs, indicating the places of the left and right. Presiding over the Parliament was its chairman, who stood at the center podium. When the Communist deputies on the right made a noise, he smiled nicely and rang his bell, but when a noise was made by the left-hand Fascist deputies, he rang the bell and looked at them very severely.

Episode 4-"Enough of Peace"

The French Parliament hall episode divided the deputies of Parliament into the place of the left and the place of the right. Eight large screens and one small one were used for this scene. Two walls stood on end next to each other and were furthest upstage; on either side of them were placed, a little further downstage, two walls on their sides. Another wall on its side led back from the vertical walls at about a 145? angle. In front of the two sets of walls on their sides were two smaller walls, both with side returns. The smallest of these created the chairman's podium. On the far sides of the stage were large lettered signs, indicating the places of the left and right. Presiding over the Parliament was its chairman, who stood at the center podium. When the Communist deputies on the right made a noise, he smiled nicely and rang his bell, but when a noise was made by the left-hand Fascist deputies, he rang the bell and looked at them very severely.

Episode 4-"Enough of Peace"

The French Parliament hall episode divided the deputies of Parliament into the place of the left and the place of the right. Eight large screens and one small one were used for this scene. Two walls stood on end next to each other and were furthest upstage; on either side of them were placed, a little further downstage, two walls on their sides. Another wall on its side led back from the vertical walls at about a 145? angle. In front of the two sets of walls on their sides were two smaller walls, both with side returns. The smallest of these created the chairman's podium. On the far sides of the stage were large lettered signs, indicating the places of the left and right. Presiding over the Parliament was its chairman, who stood at the center podium. When the Communist deputies on the right made a noise, he smiled nicely and rang his bell, but when a noise was made by the left-hand Fascist deputies, he rang the bell and looked at them very severely.

30 30 30

This content downloaded from 160.80.178.241 on Tue, 10 Mar 2015 17:19:50 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

MEYERHOLD'S D.E. 31

Episode 5-"The Lackey of French Capital" This episode involved a festive evening at the Polish President's palace that ended in

a drunken brawl and a bombing. Mikhail Zharov played Pan Tsheteshevsky in this episode, where he sang a song and danced a mazurka with Jenya Bengis. She was short and he tall, and that difference made their dance a very comic one.

MEYERHOLD'S D.E. 31

Episode 5-"The Lackey of French Capital" This episode involved a festive evening at the Polish President's palace that ended in

a drunken brawl and a bombing. Mikhail Zharov played Pan Tsheteshevsky in this episode, where he sang a song and danced a mazurka with Jenya Bengis. She was short and he tall, and that difference made their dance a very comic one.

MEYERHOLD'S D.E. 31

Episode 5-"The Lackey of French Capital" This episode involved a festive evening at the Polish President's palace that ended in

a drunken brawl and a bombing. Mikhail Zharov played Pan Tsheteshevsky in this episode, where he sang a song and danced a mazurka with Jenya Bengis. She was short and he tall, and that difference made their dance a very comic one.

This content downloaded from 160.80.178.241 on Tue, 10 Mar 2015 17:19:50 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

LLEWELLYN H. HEDGBETH LLEWELLYN H. HEDGBETH LLEWELLYN H. HEDGBETH

Episode 6-"D.E." A Soviet stadium was created by the use of a fence set across the front of the stage;

a sign in an arch in the center of the fence read "Navy Men." In front of the fence, sat a man, well-lit by a lamp from the side wall, who played the accordion as the men behind him sang and marched. The Bolsheviks triumphed in this scene, which included Bio- mechanical routines and energetic sports exercises performed by Meyerhold's students, actual sailors from the war fleets, and komsomols. They engaged in a real soccer game and danced an acrobatic polka. In this propaganda finale to the first act, the Red Army appeared tunneling its way through to America to free the world from D.E.

Episode 6-"D.E." A Soviet stadium was created by the use of a fence set across the front of the stage;

a sign in an arch in the center of the fence read "Navy Men." In front of the fence, sat a man, well-lit by a lamp from the side wall, who played the accordion as the men behind him sang and marched. The Bolsheviks triumphed in this scene, which included Bio- mechanical routines and energetic sports exercises performed by Meyerhold's students, actual sailors from the war fleets, and komsomols. They engaged in a real soccer game and danced an acrobatic polka. In this propaganda finale to the first act, the Red Army appeared tunneling its way through to America to free the world from D.E.

Episode 6-"D.E." A Soviet stadium was created by the use of a fence set across the front of the stage;

a sign in an arch in the center of the fence read "Navy Men." In front of the fence, sat a man, well-lit by a lamp from the side wall, who played the accordion as the men behind him sang and marched. The Bolsheviks triumphed in this scene, which included Bio- mechanical routines and energetic sports exercises performed by Meyerhold's students, actual sailors from the war fleets, and komsomols. They engaged in a real soccer game and danced an acrobatic polka. In this propaganda finale to the first act, the Red Army appeared tunneling its way through to America to free the world from D.E.

Act II-Episode 7-"The Fox-Trotting Europe"

Berlin was attacked by the French, but the celebrants at the Cafe Rome were untouched by the violence. The scene took place at the side of the stage, the night club's name strung between the stage wall and one of three upright screens on the right of the stage. Two screens on their sides angled toward the rear wall, and a vertical screen with a low window attached to it was at the rear of the actual playing space.

Men dressed in tuxedoes and officers and captains of the Imperial Navy sat at the cabaret tables with beautiful girls dressed ir the latest Paris fashion: knee-length back- less dresses. They all sipped cocktails through straws and looked at the stage where girls in long stockings and embroidered panties did tap dancing and the Charleston. Mikhail Zharov played the master of ceremonies and introduced the stage acts as the decadent

Act II-Episode 7-"The Fox-Trotting Europe"

Berlin was attacked by the French, but the celebrants at the Cafe Rome were untouched by the violence. The scene took place at the side of the stage, the night club's name strung between the stage wall and one of three upright screens on the right of the stage. Two screens on their sides angled toward the rear wall, and a vertical screen with a low window attached to it was at the rear of the actual playing space.

Men dressed in tuxedoes and officers and captains of the Imperial Navy sat at the cabaret tables with beautiful girls dressed ir the latest Paris fashion: knee-length back- less dresses. They all sipped cocktails through straws and looked at the stage where girls in long stockings and embroidered panties did tap dancing and the Charleston. Mikhail Zharov played the master of ceremonies and introduced the stage acts as the decadent

Act II-Episode 7-"The Fox-Trotting Europe"

Berlin was attacked by the French, but the celebrants at the Cafe Rome were untouched by the violence. The scene took place at the side of the stage, the night club's name strung between the stage wall and one of three upright screens on the right of the stage. Two screens on their sides angled toward the rear wall, and a vertical screen with a low window attached to it was at the rear of the actual playing space.

Men dressed in tuxedoes and officers and captains of the Imperial Navy sat at the cabaret tables with beautiful girls dressed ir the latest Paris fashion: knee-length back- less dresses. They all sipped cocktails through straws and looked at the stage where girls in long stockings and embroidered panties did tap dancing and the Charleston. Mikhail Zharov played the master of ceremonies and introduced the stage acts as the decadent

32 32 32

This content downloaded from 160.80.178.241 on Tue, 10 Mar 2015 17:19:50 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

Westerners danced the shimmy and the popular fox-trot. (The fox-trot was viewed in the Soviet Union as an evil to the world proletariat.) When Zharov found himself bored by his role, he recited foreign movie titles with no special meaning as asides to the audience. He also enjoyed the chance to improvise daily with fresh topicalities.

Westerners danced the shimmy and the popular fox-trot. (The fox-trot was viewed in the Soviet Union as an evil to the world proletariat.) When Zharov found himself bored by his role, he recited foreign movie titles with no special meaning as asides to the audience. He also enjoyed the chance to improvise daily with fresh topicalities.

Westerners danced the shimmy and the popular fox-trot. (The fox-trot was viewed in the Soviet Union as an evil to the world proletariat.) When Zharov found himself bored by his role, he recited foreign movie titles with no special meaning as asides to the audience. He also enjoyed the chance to improvise daily with fresh topicalities.

Courtesy ot Harvard Theatre Collection. Courtesy ot Harvard Theatre Collection. Courtesy ot Harvard Theatre Collection.

Episode 8-"Comintern" Having been thwarted in his attempts to take over the Soviet Union, Jens Boot fled

the country.

Episode 9-"The Dollar and Dynamite Is Understood Everywhere"

Episode 8-"Comintern" Having been thwarted in his attempts to take over the Soviet Union, Jens Boot fled

the country.

Episode 9-"The Dollar and Dynamite Is Understood Everywhere"

Episode 8-"Comintern" Having been thwarted in his attempts to take over the Soviet Union, Jens Boot fled

the country.

Episode 9-"The Dollar and Dynamite Is Understood Everywhere"

This content downloaded from 160.80.178.241 on Tue, 10 Mar 2015 17:19:50 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

LLEWELLYN H. HEDGBETH LLEWELLYN H. HEDGBETH LLEWELLYN H. HEDGBETH

Episode 10-"The Dinner of the Lords" A table covered by a white tablecloth and laden with food was at center stage atop

a Persian carpet. Behind it was a man dressed in white. Around him four bourgeois English gentlemen sat, smoked, conversed, and rocked in bentwood rockers. Each lord devoured another until the last died of repletion.

Episode 1 1-"Revolution in Ethnography" Five lords, led by the President of a geographic organization, raced about the stage

as the Scottish Lord Hagg rested on his walking stick.

Episode 10-"The Dinner of the Lords" A table covered by a white tablecloth and laden with food was at center stage atop

a Persian carpet. Behind it was a man dressed in white. Around him four bourgeois English gentlemen sat, smoked, conversed, and rocked in bentwood rockers. Each lord devoured another until the last died of repletion.

Episode 1 1-"Revolution in Ethnography" Five lords, led by the President of a geographic organization, raced about the stage

as the Scottish Lord Hagg rested on his walking stick.

Episode 10-"The Dinner of the Lords" A table covered by a white tablecloth and laden with food was at center stage atop

a Persian carpet. Behind it was a man dressed in white. Around him four bourgeois English gentlemen sat, smoked, conversed, and rocked in bentwood rockers. Each lord devoured another until the last died of repletion.

Episode 1 1-"Revolution in Ethnography" Five lords, led by the President of a geographic organization, raced about the stage

as the Scottish Lord Hagg rested on his walking stick.

Act Ill-Episode 12-"This Is What Has Remained From France" Cybil, played by Zinaida Raikh, Meyerhold's wife, fell in love with Hardayle.

Episode 13-"The Steel Hand" A New York Communist newspaper was attacked in the name of law and order.

Episode 14-"De Jure and De Facto"

Episode 15-"An Unexpected Dividend" Workmen went out on strike at the American Twist factory.

Act Ill-Episode 12-"This Is What Has Remained From France" Cybil, played by Zinaida Raikh, Meyerhold's wife, fell in love with Hardayle.

Episode 13-"The Steel Hand" A New York Communist newspaper was attacked in the name of law and order.

Episode 14-"De Jure and De Facto"

Episode 15-"An Unexpected Dividend" Workmen went out on strike at the American Twist factory.

Act Ill-Episode 12-"This Is What Has Remained From France" Cybil, played by Zinaida Raikh, Meyerhold's wife, fell in love with Hardayle.

Episode 13-"The Steel Hand" A New York Communist newspaper was attacked in the name of law and order.

Episode 14-"De Jure and De Facto"

Episode 15-"An Unexpected Dividend" Workmen went out on strike at the American Twist factory.

34 34 34

This content downloaded from 160.80.178.241 on Tue, 10 Mar 2015 17:19:50 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

MEYERHOLD'S D.E. MEYERHOLD'S D.E. MEYERHOLD'S D.E.

CRITICISM Despite the antipathy of some of the stricter party critics and their warnings about

the ills of risque dances and loud music, D.E. was an undeniable success with the general public. There were problems for Meyerhold, though, when audiences found the depic- tion of the Communist world deadly boring in its opposition to the glittering, sinful pleasures of the West. Throughout the Soviet scenes, the audience yawned and coughed as huge sailors in tee shirts did gymnastics and commisars gave boring speeches. Their eyes lit up, however, as they watched the temptations of the Capitalist world. The press, though interested in the critical combination of revolutionary content and new theatri- cal form, was disappointed by Meyerhold's skepticism. They felt the pictorial descrip- tions of the achievements of the October Revolution had disappeared and were instead expressed in this picture of a Communist world that was unpleasant because of its grayness and sameness. Meyerhold was accused by many of "urbanism," and of being fascinated with life in a bourgeois city, or of "infantile leftism," a dangerous misunder- standing of the world situation that could certainly encourage complacency.

On the other hand, Boris Gusman, in one of his reviews, praised this new type of political spectacle that united sharp agitation, content, and theatrical form. For him, there were three new elements in the production that made it outstanding. First, there was the simplicity of the exterior make-up, the set. Instead of old-fashioned painted sets that had been changed to cubes and later to constructions, Meyerhold used moveable walls that took part in the stage action and were well within the reach of worker's theatrical clubs. Secondly, Meyerhold used agitational posters to a great extent. Actual political slogans, citations, and portraits were introduced without slowing down the action. Again, this was a method already being used in the worker's clubs. Thirdly, the traditional theatrical platform had been overcome. Meyerhold had proven that theatre could employ almost a cinematic tempo with its rapid change of scenes.

Mologin, the man instrumental in revising D.E. in 1930, argued that Meyerhold in D.E. applied "a new method of treating the text. The text is almost like that of a newspaper, by no means theatrical; however, with the aid of a great variety of theatrical forms and by putting tremendous dynamics into the action, this text becomes light and convincing."

Other critics praised Meyerhold's contemporaneity and his didactic abilities. Werner called Meyerhold's work in D.E. "the synthesis and the ruin of 'theatre,' in the best meaning of the words, and characteristic of the present Russian situation and its future possibilities." Kvasman was amazed at the agitation strength of the play. "More workers should see it. We have to propagandize it. Here every actor is both an agitator and a propagandist of world revolution .... Thank you, comrades."

Gusman, writing again in "On the Threshhold," an article in Theatrical October, defined D.E. as a deepened agitation play of the period moving through NEP towards Socialism. The form, as well as the content, advanced the cause. "The artistic event can only be harmonious and impress the viewer when the content is organically undivided, melted in with the form, when this is like an organic whole. It is understood that any composition of art can be as strong a weapon of class struggle as our others, but it is necessary to understand that the form of this composition bound together with the content agitates in the same way as the content." Gusman explained that Meyerhold did not build on thin air in creating a newly acclaimed proletariat theatre. Instead, he worked through a provisionary period, borrowing from the richness of bourgeois cul- ture, from the sources of ancient and modem theatre.

CRITICISM Despite the antipathy of some of the stricter party critics and their warnings about

the ills of risque dances and loud music, D.E. was an undeniable success with the general public. There were problems for Meyerhold, though, when audiences found the depic- tion of the Communist world deadly boring in its opposition to the glittering, sinful pleasures of the West. Throughout the Soviet scenes, the audience yawned and coughed as huge sailors in tee shirts did gymnastics and commisars gave boring speeches. Their eyes lit up, however, as they watched the temptations of the Capitalist world. The press, though interested in the critical combination of revolutionary content and new theatri- cal form, was disappointed by Meyerhold's skepticism. They felt the pictorial descrip- tions of the achievements of the October Revolution had disappeared and were instead expressed in this picture of a Communist world that was unpleasant because of its grayness and sameness. Meyerhold was accused by many of "urbanism," and of being fascinated with life in a bourgeois city, or of "infantile leftism," a dangerous misunder- standing of the world situation that could certainly encourage complacency.

On the other hand, Boris Gusman, in one of his reviews, praised this new type of political spectacle that united sharp agitation, content, and theatrical form. For him, there were three new elements in the production that made it outstanding. First, there was the simplicity of the exterior make-up, the set. Instead of old-fashioned painted sets that had been changed to cubes and later to constructions, Meyerhold used moveable walls that took part in the stage action and were well within the reach of worker's theatrical clubs. Secondly, Meyerhold used agitational posters to a great extent. Actual political slogans, citations, and portraits were introduced without slowing down the action. Again, this was a method already being used in the worker's clubs. Thirdly, the traditional theatrical platform had been overcome. Meyerhold had proven that theatre could employ almost a cinematic tempo with its rapid change of scenes.

Mologin, the man instrumental in revising D.E. in 1930, argued that Meyerhold in D.E. applied "a new method of treating the text. The text is almost like that of a newspaper, by no means theatrical; however, with the aid of a great variety of theatrical forms and by putting tremendous dynamics into the action, this text becomes light and convincing."

Other critics praised Meyerhold's contemporaneity and his didactic abilities. Werner called Meyerhold's work in D.E. "the synthesis and the ruin of 'theatre,' in the best meaning of the words, and characteristic of the present Russian situation and its future possibilities." Kvasman was amazed at the agitation strength of the play. "More workers should see it. We have to propagandize it. Here every actor is both an agitator and a propagandist of world revolution .... Thank you, comrades."