Metropolitan Boston Transportation Authority, Old Colony ... · Old Colony Railroad Rehabilitation...

Transcript of Metropolitan Boston Transportation Authority, Old Colony ... · Old Colony Railroad Rehabilitation...

MASSACHUSETTS BAY TRANSPORTATION AUTHORITY, OLD COLONY LINE GREENBUSH LINE RESTORATION PROJECT AND SECTION 106 HISTORIC REVIEW Paper presented at AREMA 2003 Annual Conference & Exposition, Chicago, IL October 7, 2003 Author: Virginia H. Adams Senior Project Manager PAL, Cultural Resource Management Consultants 210 Lonsdale Avenue Pawtucket, RI 02860 Tel 401.728.8780 Fax 401.728.8784 July 25, 2003

ABSTRACT Cultural resources can be a critical factor in the outcome of planning, design, and construction of commuter rail projects. This paper examines federal regulatory requirements, procedures, and processes for cultural resources on the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority’s (MBTA) Old Colony Line, Greenbush Line Rehabilitation Project. The MBTA completed technical studies and consultation under Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act. A Programmatic Agreement details how effects to cultural resources will be addressed during the design-build phase, including documentation and mitigation requirements to reduce impacts to cultural resources, as well as review by an independent project conservator at specific design stages. This paper explores why the Greenbush Line project is distinctive, how the lead federal agency and community concerns shaped the process, the large-scale scope of identification, consultation, and mitigation, the role of the design-build approach in fulfilling mitigation agreements, and the current status of the project as of July 2003. Key Words: cultural resources, Section 106, commuter rail, public involvement

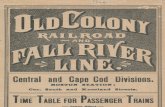

INTRODUCTION Few people today would dispute the benefits of mass transit programs that connect jobs and people, reduce vehicles on roads, and lower traffic and pollution levels. Where impacts to cultural resources are identified, they usually can be satisfactorily resolved with appropriate avoidance or mitigation measures. The Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority’s (MBTA) Old Colony Railroad Rehabilitation Project for the Greenbush Line Corridor, however, is a lesson in exceptions, a review of which may be helpful for guiding future transportation planning projects, particularly those with significant historic and cultural resource issues. Several factors have converged in the Greenbush Line to create a uniquely complex set of challenges for the sponsoring agency and its contractors, review agencies, and communities. These factors include: 1) a dense wealth of cultural resources along the corridor; 2) a highly mobilized community interested in regulatory issues under Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act and Section 4(f) of the National Transportation Act; 3) the emergence of the Army Corps of Engineers, rather than a transportation agency, as the responsible federal agency; 4) a detailed negotiated mitigation agreement with Section 106 agencies; and 5) the decision to proceed to construction as a design-build project. Finally, recent state budget concerns have affected the outcome of the project. This paper will explore these topics and will discuss why the Greenbush Line project is distinctive, how the lead federal agency guided the process, how community concerns and involvement shaped the process, the large-scale scope of identification, consultation, and mitigation for cultural resources, the role of the design-build approach in mitigation agreements and resolution of adverse effects, and the current status of the project as of July 2003. PROJECT HISTORY We begin with a brief review of the Greenbush Line’s project history. The Greenbush Line extends nearly 18 miles through the five coastal communities of Braintree, Weymouth, Hingham, Cohasset, and Scituate, south of Boston (Figure 1). The line is part of the Old Colony Railroad company system that served southeastern Massachusetts and Cape Cod beginning in the mid-nineteenth century. Commuter rail service to Boston and points in between was provided over this system for many years. After World War I, as the automobile became increasingly prevalent and ridership and service began a long decline, lines closed. The opening of the Southeast Expressway in 1959, and the destruction by fire of an important rail bridge in 1960, brought an end to passenger service on the Old Colony system (1). In 1964, the MBTA was created as a state authority. Over the next 20 years, the MBTA supported and upgraded commuter rail service over most of the former commuter rail territory in the Boston metropolitan area. In 1990, the MBTA prepared a Draft Environmental Impact Statement/Report (DEIS/R), based on the recommendations of a 1984 feasibility study, for the restoration of the Main Line and three branch service lines – the Middleborough Line, the Plymouth Line, and the Greenbush Line – of the former Old Colony Railroad. The MBTA

received comments during the DEIS/R public review process from a Citizens Advisory Committee as well as federal, state, and local agencies and officials. As a result of comments, the preferred alternative selected and presented in the Final Environmental Impact Statement/Report in 1992 would provide commuter rail service on the Main Line, the Middleborough Line, and the Plymouth Line (1). Design and construction on these lines proceeded, and all are now operating. Meanwhile, the Greenbush Line was not included in the preferred alternative and was deferred to a supplemental environmental document because of historic impact issues that were not applicable to other segments of the system. Specifically, concerns were raised regarding historic impacts in Hingham Square, where the Lincoln National Register Historic District had recently been expanded to include the rail right-of-way. In response to a directive from the Massachusetts Secretary of Environmental Affairs, the MBTA prepared a Supplemental Draft Environmental Impact Statement/Report (SDEIS/R) in 1995 for the Greenbush corridor that explored other alternatives besides commuter rail services at grade, including improvements to existing bus and commuter boat services. A variation on the commuter rail service proposed a tunnel through Hingham Square (1). Following the SDEIS/R public review process, the MBTA and then Governor William Weld announced that commuter rail restoration at grade on the Greenbush Line right-of-way had been selected as the preferred alternative. The MBTA also announced that it would not seek federal funding for the Greenbush project and that future federal formula funds would be allocated to other transit projects. Consequently, the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) withdrew from the project, and the Army Corps of Engineers (Corps) moved from being a participating agency, because of the need to issue a Section 404 wetlands permit for alterations to 10 acres of wetlands, to being the lead federal agency. The Corps took over the responsibility for coordination with the Massachusetts State Historic Preservation Office (MASHPO), known in Massachusetts as the Massachusetts Historical Commission (MHC). Following a separate review by the Corps of the environmental consequences of project alternatives, the Corps focused on the MBTA’s preferred alternative beginning in 1999. In reaction to the MBTA’s discussion to eliminate federal funding for the Greenbush Line, the Town of Hingham entered a lawsuit against the MBTA. The suit claimed that the MBTA was attempting to skirt tougher federal environmental laws. This legal negotiation occurred simultaneously with the Section 106 consultation process. SECTION 106 REVIEW The first steps in the historic preservation Section 106 process require that the responsible federal agency, in this case the Corps, delineate the project’s Area of Potential Effect or APE, and then identify and evaluate historic properties within the APE. Historic properties, as defined by Section 106, are historical and archaeological cultural resources that are listed in or eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places (National Register), or are National Historic Landmarks. The Corps delegated responsibility for identification of cultural resources to the

MBTA, the applicant. The MBTA undertook an extensive and large-scale survey effort that extended from 1994 to 2000. The 18-mile Greenbush Corridor was a settlement area for Native Americans, especially along the coastal tidal marshes. Beginning in the seventeenth century, the Greenbush area was home to colonists who established the five towns, through which the rail line travels, settlements that developed into the communities existing today. Several thousand years of human occupation have created a large and diverse inventory of cultural resources including archaeological sites, buildings, and historic districts. Numerous historic areas and resources along the Greenbush corridor predate the advent of the railroad. Prominent among them is one of the nation’s oldest mills in Scituate, as well as the Old Ship Meeting House and the General Benjamin Lincoln House, both of which are National Historic Landmarks dating from the seventeenth century, in Hingham’s Lincoln Historic District (Figure 2). The APE for four of the five towns contained historic properties already listed in the National Register before Greenbush project studies began. The Greenbush Line itself played an important role in the development of the adjacent communities. The corridor was used for passenger rail service for more than 100 years, beginning in 1849 with the South Shore Railroad commuter service from Braintree to Cohasset. By 1877 the routes expanded to become part of the Old Colony system linked to Boston. Sixteen stations served the Greenbush communities. Yet, in the late 1950s, because of poor service and increased use of private automobiles, commuter rail ridership declined and was discontinued in 1959. However, the line was not totally abandoned. Freight service continued on the Greenbush line to the Hingham shipyard branch until 1983. CSX operates freight service in the Braintree section of the line to the present day (2). Definition of Area of Potential Effect In developing the APE, the Corps and the MBTA addressed all environmental impacts likely to result from the Greenbush project and considered all impact categories that had the potential to effect cultural resources, including: noise, vibration, visual, traffic, atmospheric, construction, indirect and direct impacts. The APE for aboveground historic resources was drawn to capture all reasonably foreseeable project impacts, and to account for worst-case project impacts, using the most recent engineering data and analyses, FTA standards and guidelines, traffic analyses, noise and vibration projections, and the latest plans for six new station sites and the layover facility. An APE boundary of 400 feet from either side of the centerline of the track was conservatively established, based on projected noise and vibration effects, which were considered to have the most prominent potential for adverse effect to historic properties. This boundary extended 25 feet beyond the maximum recommended screening area for noise and vibration as set by FTA standards. This base APE was then expanded where appropriate based on a variety of factors. One instance included whether visual, traffic, and construction impacts would produce effects beyond the base. A second reflected worst-case impacts such as train hornblowing, even though because of community requests hornblowing will not occur, except in emergencies, per project design. Finally, to account for possible impacts to National Register-listed or eligible historic

districts in instances in which actual impacts might create effects in a portion of such historic districts, the APE was expanded to include the entire district. The APE for belowground archaeological resources covered all areas of proposed ground disruption. This included station sites, the right-of-way, layover sites, street widening at grade crossings, as well as locations for landscape plantings and fences, retaining and noise barrier walls. Traffic intersection improvement locations, staging areas, and wetland replacement areas outside of the MBTA right-of-way were also part of the APE (1, 2). Identification and Evaluation Once the APE was established and agreed to by the agencies, the survey identification and evaluation of historic properties began. The surveys conducted of aboveground historic and architectural resources for the Greenbush Line project identified 2,768 individual resources that were 50 years old or older within the APE. The historic architectural resources included houses, churches, schools, commercial and industrial buildings, parks, village centers, and residential neighborhoods, all dating from the late seventeenth to the mid-twentieth century. All aboveground historic resources were then evaluated using the National Register evaluation criteria. The total number of historic architectural properties that were identified and found to be already listed or eligible for listing in the National Register consisted of two previously listed and 32 eligible historic districts, containing more than 1,886 contributing properties, as well as nine previously listed and 231 eligible individual properties. Some 26 of the individual properties were located outside of historic districts, bringing the grand total of individual historic properties to 1,912. Over the 18-mile corridor, this works out to an average density of 106 historic properties per linear mile (2). Even the potential historical significance of the railroad itself was assessed. The 10 railroad bridges and six railroad-related structures within the APE were, however, evaluated as ineligible for listing in the National Register (2, 3). A series of archaeological surveys were conducted to identify potentially significant belowground resources in all areas where the proposed project would cause ground disturbance. The Greenbush project area had the potential for Native American prehistoric sites and seventeenth- through nineteenth-century historic period sites. Initial reconnaissance and identification surveys completed between 1990 and 1997 determined that some areas were highly disturbed by past activities and therefore unlikely to contain intact archaeological remains. The railroad right-of-way was included in this determination for depths of up to 3 feet as indicated by information on the cut and fill sequences of the original railroad construction. Other areas were found to have moderate or high archaeological sensitivity and were subject to additional investigations. Out of this group, several areas with potentially significant resources were identified, and archaeological evaluations (site examinations) were conducted. In all, only one archaeological site affected by the Greenbush project was found to be significant. The Cohasset Railroad Roundhouse is the remains of the 1849 roundhouse that is eligible for inclusion in the National Register, now under a paved parking lot (Figure 3) (2).

As mitigation such as fencing and landscaping began to be worked into the design even at the concept phase, the potential archaeological sensitivity of each of these locations was also assessed, although no significant sites were found. In the identification and evaluation phase, the results of the aboveground and belowground surveys were summarized in reports for each Greenbush community, a historical overview document, and archaeological reports (3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13). The actual Consensus Determinations of Eligibility are contained in a series of letters for each of the five communities between February and June 2000 from the Corps to the SHPO. In response to comments from the public and consulting parties, the Corps prepared additional letters in June and August 2000 for properties in three communities. The SHPO concurred with all the Corps determinations regarding National Register eligibility. Public Process Successful completion of this type of project planning also requires significant public involvement. Concurrent with the technical studies, the MBTA conducted an extensive community outreach program as an integral part of the Section 106 review process over a 15-month period. The program was sequenced with Section 106 the parties’ consultation as a series of meetings. Community meetings were scheduled to precede Section 106 parties consultation meetings about evaluation and about effects and mitigation so that the views from citizens could be taken into account during the consultation. Meeting notices were sent to local officials and interested parties and were posted in local news media. Transcripts of each Corps meeting’s proceedings were prepared and distributed. In all, public comments were received at 5 community meetings and 20 consultation meetings. In the meantime, two other public procedures were occurring: MBTA’s negotiations with the individual towns and the public participation process required for the state Final Environmental Impact Report (2). The MBTA conducted evening community meetings in each of the five communities to gather input and views from citizens and officials about historic and archaeological resources in their community and about project effects to these resources. Prior to each meeting, the project cultural resource inventory and large-scale mapping was circulated to local officials for their review. The Corps then held up to two consultation meetings with the SHPO, MBTA, and interested parties for each of the five communities to review the MBTA project team’s recommendations and determine the National Register eligibility of Greenbush historic properties. Several communities engaged lawyers and historic preservation consultants who made presentations at the meetings and in some cases submitted additional information about historic properties that resulted in more buildings and districts being found eligible. Public comments included questions that the project team answered, as well as requests for additional mitigation and statements concerning the historic significance of particular properties that were considered. Determination of Effect

We now turn to the Greenbush project impacts to the historic properties. As the identification and evaluation steps concluded in each community, the Section 106 process for the application of the criteria of effect and adverse effect of the undertaking to historic properties began immediately. Several key events set the stage for this phase of the process. First, the Corps requested that the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (Council) join the consultation process. Second, the MBTA was advised by the Corps, based on the Corps consultations with the Council and the SHPO, that the restoration of the Greenbush Line rail right-of-way is an adverse effect to the setting of historic properties and the pass-by of a trainset operating along the Greenbush Line should be considered an adverse effect. This guidance was applied, even though the Greenbush Line was used for train operations since 1848 and is a corridor for which restoration of such services, following their cessation in 1959, has been a long-standing transportation and economic development policy of the Commonwealth. The MBTA respectfully and strongly objected to this position regarding adverse effects. Nevertheless, the MBTA followed the Corps directive for the purposes of presenting information about the project and its potential effects during consultation meetings and in report documents (2). Third, at the same time that these meetings were occurring, the MBTA was holding ongoing mitigation discussions with each community on various topics, including historic resources. Many items requested by the towns were incorporated into the Section 106 review consultations and ultimately into the mitigation program. While the Corps and SHPO had made a finding of adverse effect for the overall project, analyses still needed to be conducted to assess the potential effects and identify possible mitigation at specific locations for all of the historic properties. The analyses had to consider each of the impact categories that had been used to draw the APE boundaries. To achieve this, project impacts and proposed avoidance or mitigation measures were categorized in four levels, paralleling the Council’s criteria of effect. These categories were used to rank the impact level of each category for every National Register eligible or listed historic district, contributing building in the district, and individually listed or eligible historic property. The ranking system took into account impact categories such as noise and vibration, which have detailed technical analyses, and FTA or other federal agency standards for assessing level of impact and mitigation thresholds. For the specific effects categories, the Section 106 impacts were broadly classified into four levels from low to high depending on the impact criteria for that category. The methodology, analytical steps, and results were presented for each community in detailed tables and annotated track plans. The MBTA sent these materials to the consulting agencies prior to each of the Corps’ effects and mitigation consultation meetings. The Corps, SHPO, MBTA, town representatives and town consultants, as well as other interested individuals and parties attended each meeting. The Council staff also was present at most meetings either in person or by remote speakerphone. In conjunction with the consultation meetings the MBTA prepared a Comprehensive Effects and Mitigation Report, February 2001 (CE&M Report) and initiated the development of a Section 106 Agreement. The CE&M Report outlined the methodology used to assess effects,

summarized the identification and evaluation results, presented the criteria of adverse effect and determination of effect, and discussed proposed measures to resolve adverse effects. It included tables and concept design level track drawings on all the historic properties and every proposed mitigation action. Historic Preservation Design Guidelines developed specifically for the Greenbush project were developed and included as an appendix. The MBTA submitted draft chapters for review by the towns and agencies and held public meetings in each community to receive comments on the draft chapters before the full report was consolidated. Programmatic Agreement and Mitigation Having come this far, the final step in concluding the initial Greenbush Line project Section 106 consultations was the completion of an agreement specifying the results and the agreed upon mitigation. The Council and the Corps determined that because of the continuing review that would extend into the design-build phase, a Section 106 Programmatic Agreement, rather than a Memorandum of Agreement, was appropriate to outline the mitigation. Mitigation, spelled out in the 40-page Section 106 Programmatic Agreement with appendices completed in 2001, is based in two areas: project design and construction, and review process and policies (14). Project design and construction incorporate an untold number of special elements and provisions to reduce impacts to historic properties in the areas of noise, vibration, visual, traffic, atmospheric, construction, indirect, and direct impacts. The MBTA had implemented measures to avoid, minimize, or mitigate adverse project impacts to historic properties, as well as other types of resources, throughout the planning process through the concept design that accompanied the Section 106 CE&M Report and the Final Environmental Impact Report. All design elements are to comply with the project’s Historic Preservation Design Guidelines. At the most general level, project-wide planning for the right-of-way, stations, and other project elements uses existing MBTA right-of-way and avoids land and building takings wherever possible. To reduce noise impacts, all grade crossings are designed without horn blowing. Continuously welded rail and resilient fastening devices, and ballasted bridge decks, will minimize noise from train operations. Noise walls will be constructed in a few locations, and homes that meet or exceed the impact threshold will receive soundproofing. Vibration impacts from train passby will be mitigated by the rail and ballast treatments as well as vibration dampening mats at specified locations. Preconstruction condition surveys of all buildings, including historic buildings, that may be affected by vibration during construction are being conducted. The Corps determined that there will be no atmospheric, indirect, or cumulative effects to historic resources from train operations, based on analyses previously completed. Traffic impacts at grade crossings will be minimal. Visual and setting effects are addressed by use of the existing right-of-way wherever possible, by minimizing unnecessary clearing and grubbing and maintaining existing vegetation wherever feasible, by keeping grade crossing medians at a minimum length, by installation of three types of fencing and tree and shrub landscape screening, by the use of materials and dark colors for fences and fixtures that support visual cohesion along the line, and by station designs sensitive to

the historic context of the area. Video and still photography documentation of the vegetation and buildings in all historic areas along the right-of-way is being completed prior to construction. In addition, the MBTA will install historic interpretive signs at stations that will explain the history of the area. A major mitigation item is an underpass in the center of Hingham in the Lincoln Historic District where historic buildings are very close to the right-of-way. The underpass will be 800 feet in length with 1,000-foot long boat sections at either end. It will be constructed using cut and cover method. Although the MBTA has agreed to build an underpass as a mitigation measure for the noise and visual effects of the train, the construction itself involves potential impacts to cultural resources, such as damage of historic buildings by construction vibration, impacts to potential archaeological resources, and the appearance of emergency ventilation stacks and equipment head house structures at grade in the right-of-way, all of which the MBTA is addressing. In Weymouth, mitigation includes construction of a shallow-cut underpass to eliminate the need for a major grade crossing and road relocation in the Weymouth Landing Historic District. This design also allows station elements to be shifted away from, or set at a lower elevation, than historic buildings. In order to achieve these goals through the design-build process, perhaps the most significant aspect of the Programmatic Agreement’s mitigation elements is the extraordinarily detailed historic review process involving federal and state agencies, a project conservator (PC), and five communities that are woven into the already complex and fast-paced design-build process. The PC is an independent review entity, selected and paid for by the MBTA, whose primary responsibility is to monitor and assess compliance of the MBTA with the Programmatic Agreement, specifically the implementation of measures to avoid, minimize, or mitigate adverse effects. The PC essentially acts as the eyes and ears of the Corps and SHPO, and is a resource for the five towns. The PC serves during the design and construction phases and for the first three years of operations. Town Mitigation Agreements Concurrent with the Section 106 PA, as part of the state environmental review process, the MBTA concluded negotiations with each of the five towns resulting in separate agreements that specify a variety of mitigation measures, concerning both historic and non-historic issues. For example, the Hingham agreement establishes a Hingham Greenbush Historic Preservation Trust Fund of $1.35 million. The fund is to be provided by the MBTA and administered by the town in accordance with guidelines for historic preservation projects that mitigate unquantifiable and presently unforeseen impacts that may be caused by the Greenbush project (2). Design-Build Review Process The mechanics of the design review process under the PA consist of review by the PC, Corps, SHPO, and towns of more than 130 design packages at the 60 percent and 90 percent levels, as well as addressing all comments prior to final design. The Project Conservator team, Epsilon

Associates, Inc., includes expertise in historic preservation planning, noise and vibration, structural, landscape architecture, and archaeology. The terms of the PA require that the PC review each design package and provide comments to the Corps, SHPO, and towns. In order to address cultural resource issues within the MBTA group for the project, the design-build team, Cashman Balfour Beatty Joint Venture, has cultural resources specialists within the design firm, STV, Inc. Furthermore, the MBTA’s program management oversight team, DMJM+HARRIS, Inc. includes PAL, cultural resource management consultants. In order to meet the design-build schedule, the MBTA’s program oversight cultural resources consultant meets once or twice a week with the design-build firm’s cultural resources staff to review upcoming design packages at the QA/QC stage. A cultural resources memo, prepared by STV and reviewed by PAL, accompanies each package stating the potentially effected resources, issues, proposed mitigation, any changes since the CE&M Report, and any deviations from the Secretary of the Interior’s Standard’s for Preservation. The PC responds with written comments, typically in less than the allotted 30 days. At that time the package is forwarded to the SHPO and the Corps for review. As design evolves through the 60 and 90 percent stages to the final design, each project element is reviewed for new elements that need Section 106 review. For example, while archaeological studies had covered the horizontal extent of work within the right-of-way, the vertical depth of bridge abutments, retaining structures, and noise walls was not presented until 60 percent design. A project-wide archaeological sensitivity assessment encompassing these design packages has been prepared. In addition to this ongoing process, a number of items had not reached concept level of design at the time the PA was written and so were called out in the PA as requiring further design and review. These included two stations, a layover facility, grade crossing treatments, several intersections, and full-scale archaeological data recovery excavations at the Cohasset Railroad Roundhouse site. These items have generated additional meetings with the Corps. Summary and Current Status In summary, the Greenbush Line project involves restoration of nearly 18 miles of former commuter rail line that operated from 1848 to1959 in five communities and passes through many historic areas. Reactivation of the Old Colony Line system is a long-term economic and transportation policy of the Commonwealth. Because of local opposition to the project and a lawsuit based on historic preservation issues, Greenbush was separated out for completion as a state-funded project, while other Old Colony Line routes proceeded with federal funding under FTA and are now in operation. The Corps is the lead federal agency, because of the need for Section 404 permit for impacts to approximately 10 acres of wetlands. MBTA completed major studies to identify historic and archaeological properties and to assess project effects. The Corps and the MASHPO determined the restoration to be an adverse effect under Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act. The Section 106 process requires public input, and the Corps and MBTA provided extensive information and sponsored numerous community and consultation meetings about cultural resources to receive comments from the towns and other

interested parties. The towns also focused on historic issues in separate negotiations with the MBTA, a parallel and simultaneous process to Section 106 consultation that influenced the Section 106 outcome. Mitigation, spelled out in a 40-page Section 106 Programmatic Agreement with appendices, is based in two areas: project design and construction, and review process and policies. Project design and construction incorporate numerous special elements and provisions to reduce impacts to historic properties. An extraordinarily detailed historic review process involving federal and state agencies, a PC, and five communities is woven into the already complex and fast-paced design-build process. The design-build approach brings new challenges as design elements that were in preliminary concept phase are advanced to more detailed levels and impacts to historic properties are better understood. As of July 2003, design and permitting of the Greenbush Line is proceeding. Governor Mitt Romney is reviewing the project, along with other transportation projects, and will reach a decision in the autumn whether to proceed to construction. Project proponents are cautiously optimistic that commuter rail service on the Greenbush Line will be restored. Whether or not it is ultimately constructed, the process undertaken so far to bring the project to this point in design-build has offered many opportunities for learning new approaches to Section 106 consultation and community negotiations. While valuable, these lessons have not been without their costs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Virginia H. Adams wishes to thank the many individuals whose hard work and dedication brought the Greenbush Line project through the Section 106 process at the MBTA, Jacobs (formerly Sverdrup Civil, Inc.), PAL, the Army Corps of Engineers, the Massachusetts Historical Commission, and in the towns of Braintree, Weymouth, Hingham, Cohasset, and Scituate. For efforts during the current phase, she also thanks staff at DMJM+HARRIS, Inc., Cashman/Balfour Beatty JV, STV Incorporated, and Epsilon Associates, Inc. In particular, she would like to thank Diana Parcon, Eric Fleming, Maureen Cavanaugh, Deborah Cox, and Suzanne Cherau.

REFERENCES

1. Sverdrup Civil, Inc. Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority Old Colony Railroad Rehabilitation Project, Final Environmental Impact Report, Transportation Improvements in the Greenbush Line Corridor, EOEA #5840. May 2001.

2. PAL. Cultural Resources Comprehensive Effects and Mitigation Report, Braintree,

Weymouth, Hingham, Cohasset, and Scituate, Greenbush Line Section 106 Review, Final Environmental Impact Report, Old Colony Railroad Rehabilitation Project. Prepared by PAL. Submitted to JE Sverdrup Inc. and Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority, February 2001.

3. McGinley Hart & Associates. Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority Old Colony

Railroad Rehabilitation Project Historic Bridge Survey. Prepared for Sverdrup Civil, Inc., 1989.

4. McGinley Hart & Associates. Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority Old Colony

Railroad Rehabilitation Project Description of Historic Resources, Hingham. Prepared for Sverdrup Civil, Inc., 1992.

5. PAL and McGinley Hart Associates, Inc. Cultural Resources Survey, Aboveground

Historic Resources, Volume I, Overview, Greenbush Line Final Environmental Impact Report, Old Colony Railroad Rehabilitation Project. Submitted to the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority and Sverdrup Civil, Inc., Boston, Massachusetts, December 1999.

6. PAL and McGinley Hart Associates, Inc. Cultural Resources Survey, Aboveground

Historic Resources, Volume II, Braintree, Greenbush Line Final EIR, Old Colony Railroad Rehabilitation Project. Submitted to the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority and Sverdrup Civil, Inc., Boston, Massachusetts, February 2000.

7. PAL. Archaeological Site Examination, Old Colony Railroad Roundhouse (WHI–HA–2),

Whitman Station Project Area, Old Colony Railroad Rehabilitation Project, Whitman, Massachusetts. The Public Archaeology Laboratory, Inc. Report No. 474-3. Submitted to Sverdrup Civil, Inc., Boston, Massachusetts, 1994.

8. PAL. Intensive Archaeological Survey and Additional Reconnaissance Survey for

Proposed Locations Along the Greenbush Line, Old Colony Railroad Rehabilitation Project, Braintree, Scituate, Hingham, Scituate, and Weymouth, Massachusetts. The Public Archaeology Laboratory, Inc. Report No. 794. Submitted to Sverdrup Civil, Inc., Boston, Massachusetts, 1997.

9. PAL. Cultural Resources Survey, Aboveground Historic Resources, Volume III,

Weymouth, Greenbush Line Final EIR, Old Colony Railroad Rehabilitation Project.

Submitted to the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority and Sverdrup Civil, Inc., Boston, Massachusetts, January 2000, and subsequent supplemental submittals, 2000.

10. PAL. Cultural Resources Survey, Aboveground Historic Resources, Volume IV,

Hingham, Greenbush Line Final EIR, Old Colony Railroad Rehabilitation Project. Submitted to the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority and Sverdrup Civil, Inc., Boston, Massachusetts, February 2000, and subsequent supplemental submittals, 2000.

11. PAL. Cultural Resources Survey, Aboveground Historic Resources, Volume V, Cohasset,

Greenbush Line Final EIR, Old Colony Railroad Rehabilitation Project. Submitted to the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority and Sverdrup Civil, Inc., Boston, Massachusetts, February 2000, and subsequent supplemental submittals, 2000.

12. PAL. Cultural Resources Survey, Aboveground Historic Resources, Volume VI, Scituate,

Greenbush Line Final EIR, Old Colony Railroad Rehabilitation Project. Submitted to the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority and Sverdrup Civil, Inc., Boston, Massachusetts, March 2000, and subsequent supplemental submittals, 2000.

13. PAL. Additional Archaeological Reconnaissance and Intensive Surveys and

Archaeological Site Examinations of the Litchfield Site (HIN-HA-07), Woodside Site (19-NF-416), and Marshview Site (19-PL-823), Greenbush Line Rail Restoration Project, Braintree, Weymouth, Cohasset, Hingham, and Scituate, Massachusetts. PAL Report No. 794. Submitted to the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority and Sverdrup Civil, Inc., Boston, Massachusetts, 2000.

14. Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. Massachusetts Bay Transportation

Authority Greenbush Line Restoration, Towns of Braintree, Cohasset, Hingham, Scituate and Weymouth. Section 106 Consultation Programmatic Agreement. February 2001.

FIGURES

1. Old Railroad Rehabilitation Project, The Old Colony Railroad System (Source: Greenbush Line Final Environmental Impact Report, May 2001, p. P-11).

2. View of Lincoln National Register Historic District, Hingham (Source: Cultural

Resource Section 106 Effects and Mitigation Report, Hingham. Greenbush Line Final Environmental Impact Report, Old Colony Railroad Rehabilitation Project. April 2000).

3. Site Plan of the Cohasset Railroad Roundhouse National Register Archaeological Site

(Source: Comprehensive Effects and Mitigation Report, February 2001, p. 43).

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3