Meta-analysis of the association between body mass index and health-related quality of life among...

Transcript of Meta-analysis of the association between body mass index and health-related quality of life among...

Meta-Analysis of the Association BetweenBody Mass Index and Health-RelatedQuality of Life Among Adults, Assessed bythe SF-36Zia Ul-Haq1,2, Daniel F. Mackay1, Elisabeth Fenwick1 and Jill P. Pell1

Objective: Obesity is associated with impaired overall health-related quality of life but individual studies

suggest the relationship may differ for mental and physical quality of life. A systematic review using

Medline, Embase, PsycINFO and ISI Web of Knowledge, and random effects meta-analysis was

undertaken.

Design and Methods: Studies were included in the meta-analysis if they were conducted on adults

(defined as age >16 years), reported an overall physical and mental component score of the SF-36, and,

or both. Heterogeneity was assessed using I2 statistics and publication and small study biases using

funnel plots and Egger’s test. Between-study heterogeneity was explored using meta-regression.

Results: Eight eligible studies provided 42 estimates of effect size, based on 43,086 study participants.

Adults with higher than normal body mass index had significantly reduced physical quality of life with a

clear dose-response relationship across all categories. Among class III obese adults, the score was

reduced by 9.72 points (95% Confidence Interval 7.24, 12.20, P < 0.001). Mental quality of life was also

significantly reduced among class III obese (�1.75, 95% confidence interval �3.33, �0.16, P ¼ 0.031),

but was not significantly different among obese (class I and class II) individuals, and was significantly

increased among overweight adults (0.42, 95% confidence interval 0.17, 0.67, P ¼ 0.001), compared to

normal weight individuals. Heterogeneity was high in some categories, but there was no significant

publication or small study bias.

Conclusions: Different patterns were observed for physical and mental HRQoL, but both were impaired

in obese individuals. This meta-analysis provides further evidence on the impact of obesity on both

aspects of health-related quality of life.

Obesity (2013) 21, E322-E327. doi:10.1002/oby.20107

IntroductionSince 1980, obesity has more than doubled worldwide and, in 2008,

1.5 billion adults aged �20 years were overweight (1). The increas-

ing prevalence of overweight and obese adults in most parts of the

world is of public health concern (2,3). It is widely accepted that

obesity causes, or aggravates, a number of medical conditions, such

as cardiovascular and musculoskeletal diseases (4,5). Obesity is also

associated with reduced life-expectancy (6-8). Previous studies sug-

gest a complex relationship between body mass index (BMI) and

health-related quality of life (HRQoL) (9,10). Overall HRQoL of

life is reduced among obese individuals, but increased among those

who are overweight (11-13). HRQoL is comprised of different com-

ponents, such as mental and physical HRQoL. A number of studies

have examined the relationship between BMI and these separate

components. Some suggest that the relationship may be different for

physical and mental HRQoL but some results are inconsistent, espe-

cially in relation to the latter. Several studies reported significant

negative associations between increased BMI and reduced mental

HRQoL (14), but others provided no relationship (15). There have

been two systematic reviews of published studies but, as yet, no

meta-analysis (9,10). These have suggested that obesity is associated

with reduced physical HRQoL but were inconclusive in relation to

the association with mental HRQoL. We undertook a meta-analysis

of the published literature to determine the separate relationships

between BMI and mental and physical HRQoL.

1 Public Health, Institute of Health and Wellbeing, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8RZ, UK 2 Institute of Public Health and Social Sciences, KhyberMedical University, Peshawar, Pakistan. Correspondence: Jill P. Pell ([email protected])

Disclosure: The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Funding agencies: Ul-Haq is sponsored by the Higher Education Commission, Pakistan (project ‘‘Development of Khyber Medical University, Peshawar’’). The authors

declare no conflicts of interest.

Received: 2 April 2012 Accepted: 31 August 2012 Published online 18 October 2012. doi:10.1002/oby.20107

E322 Obesity | VOLUME 21 | NUMBER 3 | MARCH 2013 www.obesityjournal.org

Original ArticleEPIDEMIOLOGY/GENETICS

Obesity

Materials and MethodsSystematic reviewWe conducted a systematic review of published studies in accordance

with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-

Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (http://www.prisma-statement.org/).

The following search terms were applied to the Medline, Embase,

PsycINFO and ISI Web of Knowledge databases: (obes* OR over-

weight OR BMI OR body mass index) AND (quality of life OR QoL

OR HRQoL). The search was limited to studies conducted on humans

and published in, or translated into, English. The last search was

undertaken on July 31, 2011. The resultant manuscripts were

reviewed manually, and their reference lists checked for additional

relevant studies. Studies were included in the meta-analysis if they

were conducted on adults (defined as age >16 years). SF-36 was the

most commonly used index of quality of life. Therefore, inclusion

was restricted to studies that used SF-36, and reported the overall

physical component score, overall mental component score or

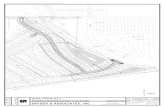

both (Figure 1). Information was extracted on the study design, size

and country, year of publication, representativeness, populations, age

FIGURE 1 PRISMA flowchart.

Original Article ObesityEPIDEMIOLOGY/GENETICS

www.obesityjournal.org Obesity | VOLUME 21 | NUMBER 3 | MARCH 2013 E323

and sex of participants, as well as the mean SF-36 scores by BMI cat-

egory and their standard deviations. Overweight was defined as a

BMI of 25.0-29.9 Kg/m2, obese as 30.0-39.9 Kg/m2 and class III obese

as �40 Kg/m2. Obese was further subdivided into class I, defined as

30.0-34.9 Kg/m2 and class II, defined as 35.0-39.9 Kg/m2.

Meta-analysisA random effects meta-analysis was undertaken to take account for

the differences in study design and location. We analyzed the

weighted mean differences in SF-36 score between individual BMI

categories and the normal weight category. I2 statistics were calcu-

lated to determine the degree of heterogeneity (16). Possible publi-

cation and small study biases were assessed visually using funnel

plots of the weighted mean differences against their standard errors,

and then tested formally using Egger’s test (17). Possible causes of

between-study heterogeneity were examined using univariate and

multivariate meta-regression models (18). To reduce the risk of type

I errors, the Monte Carlo simulation multiplicity adjustment method

was applied using 20,000 permutations. Cumulative meta-analyses

were used to explore changes over time in the pooled estimates of

effect size (19). Graphs of meta-influence were produced to examine

the influence of individual studies. All statistical analyses were per-

formed using Stata version 11.2 (Stata Corporation, College Station,

TX).

ResultsThe electronic search identified 968 publications. We used four dif-

ferent databases and when these were combined 396 duplicates were

found and excluded. An additional 32 publications were identified

from the reference lists. The abstracts of the 540 articles were

reviewed, 466 articles were found not to fulfill the inclusion criteria

and were excluded. Seventy four were deemed relevant, and the full

manuscripts were reviewed. Of these, 53 were excluded because

they did not fulfill the inclusion criteria. Among the remaining 21

publications that have used the SF-36 index, only eight studies

reported the physical and mental summary scores and thus were

included in the meta-analyses (11,15,20-25). The eight studies were

all cross-sectional (Table 1). They were published between 2000 and

2011 inclusive. Four (50%) of the studies were conducted in Europe

(15,21-23), three (38%), in North America (11,24,25), and one

(12%) in Australia (20). One study was conducted on only male par-

ticipants (24); the remainder included both sexes. The number of

participants ranged from 640 (15) to 9,771 (20), with a total of

43,086 participants. Overall 23,097 (54%) participants were either

overweight or obese. The eight studies all reported results for both

the physical and mental health components of SF-36, and they pro-

vided a total of 42 estimates of effect size for each of these

components.

Mental health-related quality of lifeOf the 42 individual estimates of the effect of BMI on mental

HRQoL, only six achieved statistical significance (Figure 2). Of

these, two suggested a higher score among overweight individuals

(22,23), and one a reduced score among class III obese individuals

(25). Among obese individuals, two suggested a reduced score

(21,22) and one an increased score (23). On meta-analysis, over-

weight individuals had a significantly higher mental health score

compared with normal weight individuals, and class III obese indi-

viduals had a significantly lower mental health score (Table 2).

Between-study heterogeneity was low for the overweight category

and moderate for the obese category. The funnel plots appeared rea-

sonably symmetrical. Egger’s test was statistically non significant (P> 0.05) for all BMI categories except for class III obese (P ¼0.018). The cumulative meta-analyses did not suggest any signifi-

cant changes in the pooled effect sizes over time. Similarly, no indi-

vidual study had a disproportionate effect on the pooled estimates in

the meta-influence plots. In the univariate and multivariate meta-

regression analyses, location, year, and participant sex were not sig-

nificantly associated with effect size.

Physical health-related quality of lifeOf the 42 individual estimates of the effect of BMI on physical

HRQoL, 33 achieved statistical significance with all of these sug-

gesting reduced scores among individuals with higher than normal

BMI (Figure 3). On meta-analysis, compared with normal weight

individuals, physical health scores were significantly lower in all

raised BMI categories (Table 2). Furthermore, there was evidence of

a dose-response relationship across the categories from normal

weight to class III obese. Between studies heterogeneity was moder-

ate in the overweight category and high in the other categories

(Table 2). The funnel plots appeared reasonably symmetrical.

TABLE 1 Characteristics of studies examining the association between body mass index and SF-36 physical and mentalhealth scores

Author Year Country N Sex Age, y Mean BMI Overweight or obese, %

Bentley (11) 2011 USA 3,710 M&F 35–89 27.6 (28.1 M, 27.0 F) 68.9

Renzaho (20) 2010 Australia 9,771 M&F �21 26.8 (27.1 M, 26.4 F) 65.9 M, 52.3 F

De ZM (15) 2009 Germany 640 M&F �21 37.3 73.9

Johanthan (23) 2009 Germany 4,181 M&F 18–65 26.3 (26.7 M, 25.9 F) 65.5 M, 48.3 F

Hopman (25) 2007 Canada 9,094 M&F �25 26.8 (26.9 M, 26.6 F) 69.0 M, 60.4 F

Larsson (21) 2002 Sweden 5,633 M&F 16–64 23.6 (24.1 M, 23.0 F) 31.6 M, 23.1 F

Yancy (24) 2002 USA 1,168 M 48–60 – 79

Doll (22) 2000 England 8,889 M&F 18–64 24.9 44

N: number; BMI body mass index: USA United States of America; M: male; F: female.

Obesity BMI and Health-Related Quality of Life Ul-Haq et al.

E324 Obesity | VOLUME 21 | NUMBER 3 | MARCH 2013 www.obesityjournal.org

Egger’s test was statistically non significant (P > 0.05) for all BMI

categories, suggesting that publication and small study bias were

unlikely. The cumulative meta-analyses did not suggest any signifi-

cant changes in the pooled effect estimates over time. Similarly, no

individual study had a disproportionate effect on the pooled esti-

mates in the meta-influence plots. On univariate and multivariate

meta-regression analysis, location, year and participant sex were not

significantly associated with effect size.

DiscussionMain finding of this studyDifferent patterns were observed for physical and mental HRQoL.

Compared with normal weight adults, those with higher BMI had

significantly reduced physical HRQoL with clear evidence of a dose

relationship across all the BMI categories. Mental HRQoL was also

significantly reduced among class III obese adults, but was not sig-

nificantly different among obese individuals and was significantly

increased among overweight adults, compared to normal weight

adults.

What is already known on this topicThere have been two previous systematic reviews, published in 1995

and 2001, of studies examining the association between BMI and

physical and mental HRQoL (10,26) but, to our knowledge, this is

the first meta-analysis of their results. Most of the published litera-

ture has reported a significant association between obesity and

impairment in the physical domain of HRQoL but a comprehensive

FIGURE 2 Forest plots of the mental health scores. (a) Overweight. (b) Obese (class I & II). (c) Class I Obese. (d) Class II Obese. (e) Class III Obese.

TABLE 2 Pooled estimates of the weighted mean difference in SF-36 physical and mental health scores by body mass indexcategory referent to normal weight

Mental health Physical health

Pooled estimate Heterogeneity Pooled estimate Heterogeneity

WMD (95% CI) P value I2 (%) P value WMD (95% CI) P value I2 (%) P value

Overweight 0.42 (0.17, 0.67) 0.001 3.1 0.416 �1.40 (�1.82, �0.98) <0.001 64.3 0.001

Obese �0.98 (�1.98, 0.03) 0.058 28.2 0.233 �3.73 (�5.54, �1.92) <0.001 83.6 <0.001

Class I 0.03 (�0.78, 0.83) 0.951 66.5 0.004 �2.54 (�3.93, �1.16) <0.001 89.9 <0.001

Class II �0.04 (�1.06, 0.99) 0.945 51.3 0.045 �3.91 (�5.10, �2.72) <0.001 68.6 0.002

Class III obese �1.75 (�3.33, �0.16) 0.031 59.6 0.016 �9.72 (�12.20, �7.24) <0.001 87.3 <0.001

WMD: weighted mean difference; CI: confidence interval.

Original Article ObesityEPIDEMIOLOGY/GENETICS

www.obesityjournal.org Obesity | VOLUME 21 | NUMBER 3 | MARCH 2013 E325

quantitative analysis is lacking. In particular, the results of published

studies have not been consistent in relation to the association

between the mental component of HRQoL and BMI. Some have

reported a significant dose-response relationship between increasing

BMI and decline in mental health (10,27,28), while others have

reported very weak or no association (15,25,29). Our study was con-

ducted in accordance with PRISMA guidelines and we searched four

databases to ensure that we identified all relevant studies. Our

pooled estimates were derived from eight studies that comprised a

total of 43,086 participants. Random effects meta-analyses were

used to take account for heterogeneity in study design and popula-

tions and provide more conservative estimates of pooled effect sizes.

What this study addsIt has been shown that obese adults are at increased risk of a num-

ber of conditions, such as cardiovascular disease (30-32), have

shorter life expectancy (33), and have reduced overall HRQoL

(34-36). There is now sufficient evidence to demonstrate that while

physical HRQoL was reduced in both overweight and obese adults,

mental HRQoL was only reduced among the class III obese. A

between-groups difference of five points in individual SF-36

domains (37), or two to three points in the overall physical and

mental component is generally considered clinically significant

(38). Therefore, the reduction in physical HRQoL demonstrated for

all above normal weight categories was clinically significant, as

well as statistically significant. The reduction in mental HRQoL

was only clinically and statistically significant in the class III

obese. There is some evidence that BMI may be more negatively

associated with mental HRQoL among women than men (11).

However, in our study, sex was not significantly associated with

effect size in either the univariate or multivariate meta-regression

analyses.

Previous studies have suggested that overweight individuals have

increased overall HRQoL (11,13,39). Our meta-analysis suggests

that this is driven by an increase in the mental HRQoL component.

Our finding that mental HRQoL was higher in overweight than nor-

mal-weight individuals is consistent with some previous studies. The

underlying reason is not yet clearly understood (40). Therefore we

can only speculate. One possible reason is that generic measures of

HRQoL might not be sensitive to the type of impairment in the

mental HRQoL which is likely to be associated with overweight

(23). In some cultures overweight is still accepted as a symbol of a

happy life (36). Also as the prevalence of overweight increases, per-

ceptions may be changing such that being overweight is perceived

as normal. Overeating may console some individuals, especially

those who are socioeconomically deprived (41).

However, their physical HRQoL is reduced. This result is consistent

with the increased risk of many conditions, such as cardiovascular

disease, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, gallstones, osteoarthritis,

and musculoskeletal disease, demonstrated in overweight individuals

(42-44).

Limitations of this studyOf the 21 selected studies, only eight reported the physical and men-

tal summary scores and were thus included in the quantitative analy-

sis. Because we did not have access to individual level data we

could not adjust for potential confounders at this level. The extent

to which individual studies measured and adjusted for potential con-

founders varied. Many studies reported only unadjusted results. This

might be a potential source of heterogeneity. Only published studies

reporting SF-36 scores were included but there was no evidence of

significant publication bias as assessed by both funnel plots and

Egger’s test. SF-36 has been translated into and validated in more

than 50 countries (http://www.sf 36.org/tools/sf36.shtml) and was

FIGURE 3 Forest plots of the physical health scores. (a) Overweight. (b) Obese (class I & II). (c) Class I Obese. (d) Class II Obese. (e) Class III Obese.

Obesity BMI and Health-Related Quality of Life Ul-Haq et al.

E326 Obesity | VOLUME 21 | NUMBER 3 | MARCH 2013 www.obesityjournal.org

the most commonly used measure. Because all of the studies were

cross-sectional, it was not possible to determine the temporal rela-

tionship and therefore exclude the possibility of reverse causation.

ConclusionsBoth physical and mental HRQoL was impaired in class III obese

individuals. There was a significant positive association between

overweight and mental HRQoL. Physical HRQoL was impaired

among overweight and obese, whereas mental HRQoL was only

affected once individuals were classified as class III obese. We have

previously shown that the relationship between BMI and overall

HRQoL varies depending on whether obesity is present in isolation

(termed ‘‘healthy’’ obesity) or is associated with comorbid condi-

tions such as hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidaemia (13). Fur-

ther research is required to determine whether these differences hold

true for both physical and mental HRQoL. This meta-analysis pro-

vides further evidence to support the injurious effects of obesity on

all aspects of health and supports the need to take action to reverse

the increasing prevalence of obesity.

VC 2012 The Obesity Society

References1. World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight. Available at: http://

www.who.int/mediacentre /factsheets/fs311/en/. Accessed 3rd August, 2012.

2. James PT, Leach R, Kalamara E, et al. The worldwide obesity epidemic. Obes Res2001;9:228-233.

3. Gulliford MC, Rona RJ, Chinn S. Trends in body mass index in young adults inEngland and Scotland from 1973 to 1988. J Epidemiol Commun Health 1992;46:187-190.

4. Colditz GA. Economic costs of obesity. Am J Clin Nutr 1992;55:503-507.

5. Must A, Spadano J, Coakley EH, et al. The disease burden associated with over-weight and obesity. JAMA 1999;282:1523-1529.

6. Olshansky SJ, Passaro DJ, Hershow RC, et al. A potential decline in life expectancyin the United States in the 21st century. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1138-1145.

7. Orpana HM, Berthelot JM, Kaplan MS, et al. BMI and mortality: results from anational longitudinal study of Canadian adults. Obesity 2010;18:214-218.

8. Flegal KM, Graubard BI, Williamson DF, et al. Excess deaths associated withunderweight, overweight, and obesity. JAMA 2005;293:1861-1867.

9. Fontaine KR, Barofsky I. Obesity and health-related quality of life. Obes Rev 2001;2:173-182.

10. Friedman MA, Brownell KD. Psychological correlates of obesity: moving to thenext research generation. Psychol Bull 1995;117:3-20.

11. Bentley TG, Palta M, Paulsen AJ, et al. Race and gender associations between obe-sity and nine health-related quality-of-life measures. Qual Life Res 2011;20:665-674.

12. Lopez-Garcia E, Banegas Banegas JR, Gutierrez-Fisac JL, et al. Relation betweenbody weight and health-related quality of life among the elderly in Spain. Int JObes Relat Metab Disord 2003;27:701-709.

13. Ul-Haq Z, Mackay D, Fenwick E, et al. Impact of comorbidity on the associationbetween body mass index and health-related quality of life: a Scotland-wide cross-sectional study of 5,608 participants. BMC Public Health 2012;12:143.

14. Scott KM, Bruffaerts R, Simon GE, et al. Obesity and mental disorders in the gen-eral population: results from the world mental health surveys. Int J Obes 2008;32:192-200.

15. de ZM, Petersen I, Kaerber M, et al. Obesity and quality of life: a controlled studyof normal-weight and obese individuals. Psychosomatics 2009;50:474-482.

16. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analy-ses. Br Med J 2003;327:557-560.

17. Sterne JAC. Meta-analysis in stata: tests for publication bias in meta-analysis.Texas: Stata Press; 2009, p 151.

18. Sterne JAC. Meta-analysis in stata: systematic reviews in health care. London: BrMed J Publication Group; 2001, p 364.

19. Sterne JAC. Meta-analysis in stata: cumulative meta-analysis. Texas: Stata Press;2009, p 55.

20. Renzaho A, Wooden M, Houng B. Associations between body mass index andhealth-related quality of life among Australian adults. Qual Life Res 2010;19:515-520.

21. Larsson U, Karlsson J, Sullivan M. Impact of overweight and obesity on health-related quality of life—a Swedish population study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord2002;26:417-424.

22. Doll HA, Petersen SE, Stewart-Brown SL. Obesity and physical and emotionalwell-being: associations between body mass index, chronic illness, and the physicaland mental components of the SF-36 questionnaire. Obes Res 2000;8:160-170.

23. Mond JM, Baune BT. Overweight, medical comorbidity and health-related qualityof life in a community sample of women and men. Obesity 2009;17:1627-1634.

24. Yancy WS, Olsen MK, Westman EC, et al. Relationship between obesity andhealth-related quality of life in men. Obes Res 2002;10:1057-1064.

25. Hopman WM, Berger C, Joseph L, et al. The association between body mass indexand health-related quality of life: data from CaMos, a stratified population study.Qual Life Res 2007;16:1595-1603.

26. Fontaine KR, Barofsky I. Obesity and health-related quality of life. Obes Rev 2001;2:173-182.

27. Kim JY, Oh DJ, Yoon TY, et al. The impacts of obesity on psychological well-being: a cross-sectional study about depressive mood and quality of life. J PrevMed Public Health 2007;40:191-195.

28. Sullivan MB, Sullivan LG, Kral JG. Quality of life assessment in obesity: physical,psychological, and social function. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 1987;16:433-442.

29. Le PC, Levy E, Loos F, et al. ‘‘Specific’’ scale compared with ‘‘generic’’ scale: adouble measurement of the quality of life in a French community sample of obesesubjects. J Epidemiol Commun Health 1998;52:445-450.

30. Bray GA. Pathophysiology of obesity. Am J Clin Nutr 1992;55:488-494.

31. Visscher TL, Seidell JC. The public health impact of obesity. Ann Rev PublicHealth 2001;22:355-375.

32. Trakas K, Lawrence K, Shear NH. Utilization of health care resources by obeseCanadians. CMAJ 1999;160:1457-1462.

33. Peeters A, Barendregt JJ, Willekens F, et al. Obesity in adulthood and its conse-quences for life expectancy: a life-table analysis. Ann Intern Med 2003;138:24-32.

34. Brown WJ, Mishra G, Kenardy J, et al. Relationships between body mass index andwell-being in young Australian women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2000;24:1360-1368.

35. Ford ES, Moriarty DG, Zack MM, et al. Self-reported body mass index and health-related quality of life: findings from the behavioral risk factor surveillance system.Obes Res 2001;9:21-31.

36. Huang IC, Frangakis C, Wu AW. The relationship of excess body weight andhealth-related quality of life: evidence from a population study in Taiwan. Int JObes 2006;30:1250-1259.

37. Ware JE. SF-36 health survey manual and interpretation guide. Boston: The HealthInstitute, New England Medical Centre; 1993.

38. Ware JE. SF-36 physical and mental health summary scales: a user’s manual. TheHealth Institute: New England Medical Centre; 1994.

39. Vasiljevic N, Ralevic S, Marinkovic J, et al. The assessment of health-related qual-ity of life in relation to the body mass index value in the urban population of Bel-grade. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2008;6:106.

40. Carpenter KM, Hasin DS, Allison DB, et al. Relationships between obesity andDSM-IV major depressive disorder, suicide ideation, and suicide attempts: resultsfrom a general population study. Am J Public Health 2000;90:251-257.

41. Crisp AH, McGuiness B. Jolly fat: relation between obesity and psychoneurosis ingeneral population. Br Med J 1976;1:7-9.

42. Manson JE, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ, et al. Body weight and mortality amongwomen. N Engl J Med 1995;333:677-685.

43. Field AE, Coakley EH, Must A, et al. Impact of overweight on the risk of develop-ing common chronic diseases during a 10-year period. Arch Intern Med 2001;161:1581-1586.

44. Wyatt SB, Winters KP, Dubbert PM. Overweight and obesity: prevalence, conse-quences, and causes of a growing public health problem. Am J Med Sci 2006;331:166-174.

Original Article ObesityEPIDEMIOLOGY/GENETICS

www.obesityjournal.org Obesity | VOLUME 21 | NUMBER 3 | MARCH 2013 E327