Mesopotamian Art

description

Transcript of Mesopotamian Art

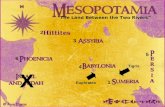

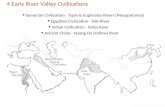

The Peoples of Mesopotamia

The SumeriansThe AkkadiansThe BaybloniansThe AssyriansThe Neo- Babylonians

See the site for detailed information:http://www.eyeconart.net/history/ancient/mesopotamian.htm

21st - 17th c BCE Mesopotamian Babylonian Sculpture

The cuneiform script underwent considerable changes over a period of more than two millennia. The image below shows the development of the sign SAG "head" (Borger nr. 184, U+12295)

Stage 1 shows the pictogram as it was drawn around 3000 BC. Stage 2 shows the rotated pictogram as written around 2800 BC. Stage 3 shows the abstracted glyph in archaic monumental inscriptions, from ca. 2600 BC, and stage 4 is the sign as written in clay, contemporary to stage 3. Stage 5 represents the late 3rd millennium, and stage 6 represents Old Assyrian ductus of the early 2nd millennium, as adopted into Hittite. Stage 7 is the simplified sign as written by Assyrian scribes in the early 1st millennium, and until the script's extinction.

The Epic of GilgameshThe Epic of Gilgamesh is, perhaps, the oldest written story on Earth. It

comes to us from Ancient Sumeria, and was originally written on 12 clay tablets in cunieform script. It is about the adventures of the historical King

of Uruk (somewhere between 2750 and 2500 BCE).

Art of the ancient civilizations that grew up in the area around the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, now in Iraq. Mesopotamian art was largely used to glorify

powerful dynasties, and often reflected the belief that kingship and the divine were closely interlocked.

Sumerian (3500–2300 BC) The first of the powerful Mesopotamian civilizations, Sumer was concentrated in the cities of Ur, Eridu, and Uruk in

southern Mesopotamia. The Sumerians built temples on top of vast ziggurats (stepped towers) and also vast, elaborately decorated palaces. Sculptures

include erect, stylized figures carved in marble and characterized by clasped hands and huge eyes; those found in the Abu Temple, Tell Asmar, date from

2700 BC. Earlier sculptures in alabaster, such as the Female Head (3000 BC; Iraq Museum, Baghdad), show a greater naturalism and sensitivity. Inlay work is seen in the Standard of Ur (2500 BC), a box decorated with pictures in lapis lazuli, shell, and red sandstone. The Sumerians, who are thought to have invented writing about 3000 BC, produced many small, finely carved

cylindrical seals made of marble, alabaster, carnelian, lapis lazuli, and stone. The Sumerians, like the ancient Egyptians who were more or less their contemporaries, believed in an afterlife, and so their tombs were well

furnished with art, furniture, and other items to prepare them for the next world.

Faces are dominated by very large eyes; but, for reasons we might take for granted, artists of many cultures have placed emphasis on eyes.

The statues found at the Abu Temple in Tell Asmar from c. 2700 BCE

Helmet of King Meskalamdug, c. 2400 BCE

Akkadian (2300–2150 BC) The Akkadian invaders quickly assimilated Sumerian styles. The stele (decorated upright slab) Victory of Naram-Sin (2200 BC; Louvre, Paris), carved in relief, depicts a military campaign of the warlike Akkadians. The technical and artistic sophistication of bronze sculpture is illustrated by the Head of an Akkadian King (2200 BC; Iraq Museum, Baghdad).

Assyrian (1400–600 BC) The characteristic Assyrian art form was narrative relief sculpture. Unlike the other southern Mesopotamian peoples, the Assyrians had access to large quantities of stone, and their many carved reliefs have consequently survived well. These shallow carvings were used to decorate palaces, for example, the Palace of Ashurbanipal (7th century BC). Its finely carved reliefs include dramatic scenes of a lion hunt, now in the British Museum, London. Winged bulls with human faces, carved partially in the round, stood as sentinels at the royal gateways (Louvre, Paris).

Mesopotamia, Nimrud, Head of a Woman, late 8th century BCE, ivory plaque, originally part of furniture. This piece is listed on the Oriental

Institute's database of treasures that have been lost or stolen from Iraq.

Babylonian (625–538 BC) Babylon came to artistic prominence in the 6th century BC, when it flourished under King Nebuchadnezzar II. He built the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, a series of terraced gardens. The Babylonians practised all the Mesopotamian arts and excelled in brightly coloured glazed tiles, used to create relief sculptures. An example is the Ishtar Gate (about 575 BC) from the Temple of Bel, the biblical Tower of Babel (Pergamon Museum, Berlin, and Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York).

© Research Machines plc 2007. All rights reserved. Helicon Publishing is a division of Research Machines plc.

A Babylonian relief sculpture of a bull made of brightly glazed tiles on the restored Ishtar Gate. The original sculpture dates from around 575 BC and stood on the gate of the Temple of Bel, the biblical Tower of Babel in Babylon.

Persia, The Hanging Gardens of Babylon, sixth century BCE. Accounts indicate that the garden was built by King Nebuchadnezzar II, who ruled the city for 43 years starting in 605 BCE, and that he built them to cheer up his homesick wife, Amyitis. Medes, the land she came from was green, rugged and mountainous, and she found the flat, sun-baked terrain of Mesopotamia depressing, so the king decided to recreate her homeland by building an artificial mountain with rooftop gardens. The Hanging Gardens weren't actually "hanging", but instead were "overhanging" as in the case of a terrace or balcony.