Memory as a social and discursive practice in monuments · perienced reality.2 Seeing memory as...

Transcript of Memory as a social and discursive practice in monuments · perienced reality.2 Seeing memory as...

29

Nordisk Museologi 2004 • 1, s. 29–42

Memory as a social

and discursive practice

in monuments

A case study of the Tapio Rautavaara Monument.

Tuuli Lähdesmäki

Monuments are protagonists in many historical narratives. They “tell” fascinating storiesof past times and past heroes and “advise” us to commemorate and reminisce. But who isactually doing the telling and to whom? How are the stories formed? In monuments thepast and present, memory and history, meet in a complex way and form a structure ofmeanings reflecting the narratives and values of the so-called imagined community.Discursive and narrative practices play a crucial role in the formation and productionof the meanings of monuments.

understood as a proper sculpture or a goodwork of art. Concepts of good art may vary,but the idea of good art as the bearer of mem-ory in a proper way seems to be common.

Several writers consider remembering as asocially structured practice.1 This aspect of me-mory derives from the late nineteenth and ear-ly twentieth century sociological theories. Ac-cording to this view remembrance and com-memoration are formed in social interaction,in talk and performances. This aspect of theformation of memories is particularly interes-ting in researching monuments, which are cle-ar examples of social and discursive meaning-making processes. The focus lies not only inquestions: who is remembering, why and howdoes the commemoration occur, but also how

Remembrance is the main function of monu-ments. Without the memorial purpose thewhole concept of the monument loses its mean-ing. Monuments also serve many other func-tions, such as ideological, political (nationaland regional) and aesthetic. These other func-tions of monuments are closely connected toremembrance and commemoration. Ideologi-cal and political functions especially are insep-arable from the memorial aspects of monu-ments: remembering is an ideological and po-litical practice. Even the aesthetic is related toremembrance in monuments. To carry thememory well means that the form of the monu-ment must meet one´s concept of good art. Itis easier to link the commemorative functionto the monument if its form is accepted and

30

Tuuli Lähdesmäki

a remembered person or event, a rememberingcommunity and its identity are discursivelyproduced.

In this paper I will examine how memory isbound to monuments as a social and discur-sive practice. I will illuminate this practicethrough a case study of a monument to theFinnish singer, athlete and actor Tapio Rauta-vaara (1915–1979). His monument, calledDream of a Wanderer (fi. Kulkurin uni), wasraised in the year 2000 in the residential areaof Oulunkylä in Helsinki, where Rautavaaralived most of his life. In the monument thepast and present, individual and collective,memory and history, intertwine to form adiscursive texture.

Problematising individual

and collective memory

In projects to erect monuments the generalpublic or a specific community is encouragedto recall a past event or a person. Many news-paper articles are written during such projectsabout the importance of the memory and themeaning of elevating the person or event fromoblivion into the minds of members of thecommunity. In these texts those who are rais-ing the monument urge the public to engagein individual commemoration, to meet themonument with subjective reminiscences andto relate it to their personal memories of theparticular person or event. What does indi-vidual reminiscing mean in terms of monu-ments? If remembering is considered a socialpractice, the idea of the ‘individual memory’and ‘subjective commemoration’ will also havesome sort of social content.

The social understanding of individualmemory was formulated as early as in the socio-logical texts of Emil Durkheim and Maurice

Halbwachs. They saw that humans are alwayssocial beings and they remember and forgetaccording to the memory frames and practicesof the group to which they belong. Theseframes are defined by a culture and contexts ofcultural participation. Individuals are membersof a variety of such contexts which is why theyremember according to several social frames,which emphasise different aspects of the ex-perienced reality.2

Seeing memory as this kind of social prac-tice still allowed some space for the concept ofindividual reminiscence. In fact, for a long timeindividual and collective were kept as separateconcepts in research into memory.3 In manytexts this separation is still maintained.

In recent studies of memory in the field ofcultural psychology many writers have locatedmemory in culture and stressed memory as acultural practice.4 In this cultural understan-ding of memory, the separation of the indivi-dual or personal memory and the collectivememory is seen as unnecessary. Consideringthe manifold layers of the cultural fabric thatweaves together individual, group and society,the idea and category of an isolated and auton-omous individual becomes meaningless, asJens Brockmeier writes.5 Understanding theindividual and collective memory as a wholemeans that the earlier categories of individualand collective, private and public, are now seenin continuous interaction, interplay and mu-tual dependence, fusion and unity. Remembe-ring and forgetting are also understood as inter-dependent features of one solid phenomenon.Seeing forgetting as being closely connected toremembering is not a radically new aspect, butseveral writers in recent years have emphasisedthe importance of forgetting in memory-making. Forgetting and modifying a givenmemory’s intention or implication is as much

31

Memory as a social and discursive practice in monuments

a part of memory-making as is remembering.6

If we reject concepts of the individual andcollective memory, what should we then callthe practise of reminiscence? In texts differentconcepts seem to be used in explaining mem-ory practice. Different concepts are used to de-scribe similar acts but on the other hand, sim-ilar concepts might be given different meaningsaccording to the research aspect. Brockmeier,who emphasises the interplay of the individu-al and the collective in memory-making, usesa concept of cultural memory.7 Another con-cept, which refers to a combiniation of the in-dividual and the collective, is the concept ofsocial memory, as used e.g. by Peter Burke.8

However, the concept of social memory issometimes used in opposition to individualmemory (e.g. in some of Brockmeier’s texts).9

Concepts of historical memory and collectivememory explain memory more clearly as theopposite of individual or personal memory. Theconcept of collective memory was formulatedby Durkheim and as Adrian Forty writes“since Durkheim […] there has been a tenden-cy to confuse the memory of the individualwith the memory of societies“.10 It seems thatthe idea of separate categories of individual andcollective remembering and forgetting existstrongly, especially in historians´ studies ofmemory.11 Concepts of a public memory anda popular memory are more difficult to fit intoa juxtaposition of individual and collective orinto the combining concept of cultural mem-ory. For John Bodnar the public memoryemerges from the intersection of official andvernacular cultural expressions. It is understoodas a body of beliefs and ideas about the pastand as a site of contest between competingvoices, a site that is created in a variety of pub-lic forums, where various parties representingvarious parts of society exchange views about

beliefs, ideas and the past.12 The concept ofpopular memory has been used by oral histori-ans to refer to commonly held representationsfound in the oral accounts people give of pastevents, traditions, customs and social prac-tices.13 These various concepts of memory formdialogical relationships. The formation of theconcepts also has a historical dimension.

In this paper I understand memory as theconcept of cultural memory, referring to thecomplex structure of the memory-making pro-cess. In monuments both aspects of memory,individual and collective, seem to be presentsimultaneously and are intertwined so tightlythat it is difficult to distinguish and separatethem. The concept of cultural memory notonly mixes the traditional categories of mem-ory, it also emphasises a mixture of experienc-es of the past and present. Brockmeier has de-scribed memory as a movement within a cul-tural discourse that continuously combines andfuses the now and then, the here and there.14

Seeing the past and present in a changing in-terplay in the memory-making process is afruitful starting point when observing monu-ments. The meaning-making of monumentscombines: historical and fictive stories (textsor pictures etc.), which have been told about aremembered person or event, stories that com-ment or interpret these historical or fictive sto-ries, memories of people who experienced theevent themselves or met the deceased person-ally, and memories which have been formedfrom the bases of all of these written or oralstories. Memories transform easily into storiesand stories feed memories.

If the memory and remembering is locatedin culture, the observation of this phenomenoncan be carried out by and through other cul-tural practices: narrative and discourse.15 Nar-rative is crucial among memory practices: me-

32

Tuuli Lähdesmäki

mory practices are narrative practices, as Brock-meier emphasises.16 In researching monumentsit is clear that meanings do not just originatefrom the monument as a sculpture: meaningsare produced in texts, in narratives and dis-courses. If the memory is understood as a nar-rative practice, it can be said that texts and dis-courses influence how the past is remembered.David Middleton and Derek Edwards, whohave studied memory as a discursive practice,state that the media and their concomitantmodes of representation and discourse, constrainor shape what can and cannot be thought, said,written and remembered.17

The remembrance, forgetting and narrativeare elements in the creation of power. ‘Wrong’memories or narratives may seem as a threat inthe eyes of committee members, who are rais-ing a monument to exalt the ‘right’ memoriesand interpretations of the past. ‘Wrong’ mem-ories might undermine the importance andvalidity of commemoration.18 It would be idealfor the memory activators, if varying interpre-tations could be drawn within the correctnessof the one ‘big narrative’. As Shawn Rowe, Ja-mes Wertsch and Tatyana Kosyaeva put it: the“linking of one’s life story to some overarchingnarrative of a collective is perhaps the dreamof leaders of collectives who wish to create com-mitted, loyal members of the ‘imagined com-munity’“.19 In the case of the Tapio Rautavaa-ra Monument, the unifying elements of an‘imagined community’20 were Finnish popu-lar traditional music (fi. iskelmä, sw. schlager)and a proud sports tradition.

Remembering a Finnish

“javelin and troubadour hero“

and a “legend of sports

and entertainer“21

The faster Western societies change in late andpost-modern times and traditions, religion andethics lose their influence, the more energyflows into public practices, institutions and theestablishment of artefacts that conjure up cul-tural memories.22 This can also be perceivedin the production of monuments in Finland:new monuments are constantly being raised.Reminiscing and remembering cannot be prop-erly understood without taking into accountthe social functions they fulfil.23 What is thisfunction in the Tapio Rautavaara Monument?Pierre Nora states, that the need for memoryis a need for history.24 Is the need for memoryin the case of the Rautavaara Monument theneed to raise the popular singer and entertai-ner into the category of official and ‘serious’cultural heroes? The Rautavaara Monumentreflects well the so-called memory crisis inWestern cultures.25 In the 1990s many popu-lar heroes, such as well-known athletes, or even‘antiheros’ were given a monument in Finlandor were the subject of discussions about a mo-nument. Getting a monument no longermeans that the deceased has been institutional-ised as a great man, or vice versa; the categoryof so called great men has broken open or haschanged.

The Tapio Rautavaara Monument projectwas started by the Tapio Rautavaara Society,with Rautavaara’s daughter as chair. The So-ciety wanted to honour Rautavaara’s multi-faceted career and life’s work with a figurativesculpture which should be easy to recognise ashim. The Society looked for an artist for a whilebefore deciding on the Finnish artist Veikko

33

Memory as a social and discursive practice in monuments

Myller (b. 1951). His sketch satisfied the So-ciety, and he was commissioned to begin workon the sculpture while the Society concentra-ted on raising money by organising variousevents, seeking donations and later by sellingminiature models of the monument. The fin-ished monument was unveiled on Tapio’sname’s day (18.6.) in a celebration, at whichmany popular singers of iskelmä music per-formed songs recorded by Rautavaara. After thecelebrations at the monument festivities con-tinued in Rautavaara’s favourite restaurant witha karaoke contest with Rautavaara’s songs.

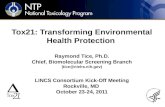

What aspect of Rautavaara does the monu-

ment represent? The monument consists ofthree elements: a figure of Rautavaara wearinga jogging suit jacket and playing the guitar, aswan standing in front of the figure, and a pla-que next to the figure and the swan with somefacts about the sculpture on one side and a shortpresentation of Rautavaara on the other. Ac-cording to this presentation Rautavaara was anathlete, singer, entertainer and movie actor. Hisgreatest sporting achievements are listed, anOlympic gold medal javelin in 1948 and aworld championship team gold medal in arch-ery in 1958. The sculpture combines Rautava-ara as an athlete and a singer. He is wearing

Veikko Myller, Dream of a Wanderer (fi. Kulkurin uni), the Tapio Rautavaara Monument, 2000, in Helsinki.Bronze (the figure 3 m, the swan 1,6 m). Photo TL.

34

Tuuli Lähdesmäki

the popular jogging suit jacket which Finnishathletes used in the London Olympic Gamesin 1948 and which has become for Finns a sortof symbol of Finnish sport and even of Fin-nishness. On the front of the blue and whitejogging suit jacket there is the text Suomi (Fin-land).

The guitar strongly symbolizes Rautavaaraand his music. He was one of the most famoustouring singers in Finland after the war, per-forming in dances and at evening shows withother artists. Rautavaara’s success as a singercoincided with an increase in the popularity ofFinnish traditional dance-floor culture in the1950s. Rautavaara’s role as a singer unifies hisroles as actor and entertainer: his role in films

and evening shows was often to entertainothers by playing the guitar and singing. Mostof the songs Rautavaara performed were shortstories about various human destinies, lives andmemories of past times, or exuberant tales ofthe carefree life. In many songs the free andeasygoing life of a wanderer is seen in a ro-mantic and idealized light. One of Rautavaara’smost popular songs is called A Wanderer and aSwan (fi. Kulkuri ja joutsen), in which the nar-rator, who calls himself a wanderer, sees adream of a swan with whom he gets thechance to fly and wonder at the beauty of thecountryside below. After the dream the nar-rator hopes to see the swan one more time. Inthe Rautavaara Monument this encounter is

Veikko Myller, Dreamof a Wanderer (fi.Kulkurin uni), theTapio RautavaaraMonument, 2000, inHelsinki. Bronze (thefigure 3 m). A close-upof the figure. Photo TL.

35

Memory as a social and discursive practice in monuments

made visible. The narrator who, in the monu-ment, has become one with the real Rautavaa-ra, meets the swan of the dream. Different timeand reality levels fuse: a guitar playing athletewho performed in the 1948 Olympic Games,a popular singer, a narrator of songs and themyth of Rautavaara as a wanderer himself allcome together. The swan, which is the Finnishnational bird (whooper swan, lat. Cygnus cyg-nus), refers not only to Rautavaara’s songs butalso to the Finnish countryside, the fatherlandand Finnishness.

The past is brought to the present in the Rau-tavaara Monument in several ways. This pastis victorious and successful, it boasts sports vic-tories and good music. There is a strong senseof nostalgia in the monument to the popularsinger, whose live audience grows older at thesame time as the whole Finnish traditionaldance-floor culture has changed. In the late1960s other forms of entertainment and mu-sic replaced evening shows and traditionaldancing, and new sensational tabloids dis-mantled old myths of singer heroes.26 The tra-ditional dance-floor culture and iskelmä musicexperienced a revival in the 90s alongside newTV and radio programmes concentrating ontraditional Finnish popular music, the appear-ance of new popular iskelmä singers and thehuge success of the tango singing contest or-ganised annually in Seinäjoki, in Ostroboth-nia. As Walter Benjamin writes, cultural phe-nomena take on a new sense of importance andbeauty when they are coming to an end.27

When the Finnish traditions of the 50s and60s were threatening to fade away, they werekept alive by nostalgia, remembering and revi-talising.

The same phenomenon can be observed inFinnish movies of the late 1990s. The long-suffering Finnish film industry experienced a

huge boom at the end of the 90s. In most ofthe films which were good box-office success-es, events were set in the countryside and inFinland’s recent historical past. Several filmstold the story of a popular Finnish singer frompast decades. In 1999 Timo Koivusalo’s filmThe Swan and the Wanderer (fi. Kulkuri ja jout-sen) was shown in the cinemas. The film tellsthe story of Tapio Rautavaara and other enter-tainers of the 50s and 60s. The atmosphere inthe film is very nostalgic. The Tapio Rautavaa-ra Society’s monument project and Koivusalo’sfilm have interesting parallels: they ‘advertised’each other and supported the common aimsof commemorating and remembering Rauta-vaara at the same time strengthening the mythof Rautavaara as a free and talented wandererhero, who saw the whole spectrum of life inhis journeys. The director, Koivusalo, empha-sised this aspect of Rautavaara in his speech atthe unveiling ceremony.

Remembering seems itself a phenomenonwhich characterises Rautavaara as a person. Inthe film Rautavaara is several times represent-ed recalling past times. As many of his songsdeal with memories and reminiscences fromthe past, the narrator in the songs and Rauta-vaara often become one. Reminiscence is in factrelated inseparably to one genre of Finnish is-kelmä music where the focus is on an indivi-dual who is recalling events and emotions fromthe recent past.28 Is the Rautavaara Monumentactually a picture of memory, a picture, wheredifferent aspects of a cultural memory of theentertainer flash into visibility at the same time?

The pose in the Rautavaara Monument mayawaken memories among those who followedthe 1948 London Olympic Games and laterRautavaara’s career as a singer and entertainer.Rautavaara had a guitar with him in Londonand there are many press and fan photos where

36

Tuuli Lähdesmäki

he is playing the guitar dressed in the Suomijogging suit. The guitar playing Rautavaara is,of course, printed on many tour posters andfan pictures. It is not only nostalgia, but alsofamiliarity that determines interpretations of themonument. It is no wonder that after the un-veiling of the monument, a newspaper wrote:“Now the wanderer has returned home from along tour“.29

The cultural hero has been brought to his

rightful place strengthening the value and ap-preciation of the local community.30

Meanings of the monument are also prod-uced in narratives told in newspapers, magazin-es and books. The hero story of Rautavaara asa poor, sick boy from modest circumstanceswho achieves unexpected success through de-termination, hard work and luck, was alreadyformed in texts after the winning of the goldmedal in 1948.31 In this story the poor and

37

Memory as a social and discursive practice in monuments

modest win, and hard work and a humblecharacter are rewarded in the end. The narra-tive of “a noble athlete“32 and “one of the lastathletes permeated by a pure Olympic ideal“33

was also repeated in newspapers during thediscussion about the monument. Apart fromthe narrative of a sports hero, the discussionsproduce a narrative of a charming “troubadourhero“,34 loved by the whole nation. This nar-rative is more sentimental: the troubadour is a

wanderer, who amuses others, but is himself a“lonely vagabond“,35 In the end a vagabond,who “has an eternal place in the heart of theFinnish nation“,36 is granted official thanks (amonument) and becomes a legend. The vaga-bond has stopped touring and returned home,in the form of a monument. Thus the monu-ment produces a home-coming narrative or anarrative of reunion. The hardness of the tour-ing lifestyle, practice, planning, boredom,

Tapio Rautavaara performing ontour in Varkaus in 1978, a yearbefore he died. The repetitive use ofthis kind of picture constitutes thecommon imagery of Rautavaara as aperforming artist. Photo: HelgeHeinonen, Suomen Urheilumuseo.(right).

Tapio Rautavaara plays the guitarin the London Olympic Games in1948. Similar photos werepublished in newspapers,magazines and fan pictures.Photo: Suomen Urheilumuseo.(left).

38

Tuuli Lähdesmäki

heavy drinking or homesickness are not a partof any of these narratives. Those aspects areforgotten.

The narrative repeats the discourse of free-dom: the wanderer is led by his heart but stilltakes responsibility for himself. “The image ofthe real wanderer does not include being asocial bum“,37 as one magazine wrote. In a way,the role of Rautavaara as an honest, humble,carefree and child loving wanderer, is remi-niscent of the tramp portrayed by CharlieChaplin. These wanderer roles differ stronglyas regards their emphasis on manliness. Theidea of freedom and independence seems tobe part of a masculine discourse of Rautavaa-ra. Other characteristics that are related to thisdiscourse, are notions of Rautavaara’s “deepmanly voice“,38 “roughly tender manliness“,39

his handsomeness, honesty and a combinationof deeds (sport) and emotions (singing). “Alsotender emotions are accepted from a hero“,40

but even “in the role of a poet Rautavaara stayswithin the measures of a man“.41

Forming memories and identities

Brockmeier writes that that which binds indi-viduals together into a cultural community isa world view, rooted in a set of social rules andvalues, as well as in the shared memory of acommonly inhabited and similarly experiencedpast. It forms a cultural sense of belonging,which at the same time binds individuals intoa culture and the culture into the individual’smind.42 This sense of belonging seems to ap-proach the sense of identity. Social rules andvalues and shared memories are essential in theformation of the identity and integrity of acommunity.43 Or as George Iggers writes, col-lective memory and collective identity largelycoincide.44 What kind of community or who-

se identity is the Rautavaara Monument serv-ing?

The national emphasis is clearly visible inthe monument and easily interpreted fromdiscussions about it. One could state that themonument underlines certain Finnish icons, aswan and the Suomi jogging suit, and refers tothe national clichés of iskelmä music and Finnsas a sporting nation, particularly successful injavelin throwing. The figure of Rautavaara be-side a swan refers to the Finnish countryside.The ideal setting for the traditional Finnishdance-floor culture is the countryside. Danc-ing often takes place near a lake with birch trees,in the light of a summer evening. Nature isalso typically present in iskelmä music, wherenature and emotions are intertwined: emotionsare described in terms of different natural phe-nomena.45 In the aims of the Tapio Rautavaa-ra Society and in discussions in the newspapers,the monument is endowed with the meaningthat it praises the national character and for-mulates true Finnishness. The past, which isremembered, is seen as the past shared by allFinns, and they are expected to recognise thefigure in the monument and know Rautavaara’ssongs and sporting achievements. The past,connected to Rautavaara, is seen as a base ofcommon experience, from which the sense ofcultural belonging, the Finnish identity is in-herited. In fact, this past is shared only by acertain segment of the Finnish people. Yet indiscourse it was made the element which uni-fied Finns. Seeing itself as a representative ofthe nation, the Society could write after theunveiling that “at last the Finnish nation hadgot the monument it had been waiting for“.46

According to Hall, positioning is the core ofcultural identities. Identity is not just one singleunifying experience, but is produced within thediscourses of history and culture by taking

39

Memory as a social and discursive practice in monuments

positions.47 In the case of the Rautavaara Mo-nument, the national positioning describedabove combines with a strong local discourse.Placing the monument in Oulunkylä, whereRautavaara lived most of his life, was support-ed by the Helsinki Art Museum, for example,because “Oulunkylä (…) deserves a monumentof its own, that creates a strong local identi-ty“.48 In some newspapers Rautavaara was alsopraised as a “son of our village“.49 His mem-ory was emphasised in many local practices:Rautavaara sightseeing tours and dances wereorganised and a café next to the monumentstarted to serve Rautavaara pastries. The figurein the monument is annually crowned with alarge hat on Tapio’s day, a reference to Rau-tavaara’s popular song Grandfather’s Straw Hat(fi. Isoisän olkihattu). Even though the monu-ment and Rautavaara are used to form localityand a local identity, there is not just one localidentity in a community, but many differentlocal identities.

From reminiscing to making

history

The cultural memory of a community may bedistributed unequally in the minds of its mem-bers, but this distributed memory can bebrought together at moments such as ritualperformances.50 Raising a monument is a rit-ual, which visualizes the cultural memory of acommunity or at least the ‘official’ or domi-nant picture of it. Even more effective in en-suring things are remembered, are periodicalorganised rituals or festivities. Durkheim em-phasised that in order to retain the collectivememory of some great person or event, societymust set aside a time for people to periodicallyassemble and to contemplate the commonthings they cherish and wish to preserve.51 But

the more practices, performances and objectsare used in the remembering, the more the re-membering is transformed into the making ofhistory. Visible, public traces of memory mayeasily become part of written history.

Nora states that with the appearance of thetrace, we leave the realm of true memory andenter that of history.52 For Nora memory andhistory are in many respect conflicting con-cepts. Commemoration is needed to ensurecertain things are remembered, are present inthe community, things that would otherwisedisappear and be forgotten. Nora uses the con-cept of lieu de mémoire to refer to sites, objectsand phenomena which are symbolic elementsof the memorial heritage of a community.53

These lieux de mémoires emerge, when mo-ments in history are plucked out of the flow ofhistory and then returned to it.54 Even thoughit is not clear whether Nora by history meansthe history as past time or history as narration,the idea of the emergence of lieux de mémoiresis fruitful. As in the case of monuments, his-tory as past time has lived in different mem-ories until it is turned in a monument into avisible object and into a history as a narration.Different memories may still be alive, but fromnow on the monument expresses the officialnarration of history dominating the variety ofmemories, not only by hindering other typesof narratives from being heard, but also by in-fluencing the formation of memories.

It would probably be an exaggeration to ap-ply Nora’s concept to the Rautavaara Monu-ment.55 However, the monument was produc-ed discursively as a concrete place of remi-niscence, a “common meeting place for resi-dents of Oulunkylä“,56 where “one can rest ona bench and, say, remember Tapio’s songs lov-ed by many“,57 but also as an abstract spacewhere something very Finnish is crystallised.

40

Tuuli Lähdesmäki

Conclusions

The Tapio Rautavaara Monument can be in-terpreted as an expression of cultural memory.Cultural memory becomes concrete in texts,performances, narratives and interpretations ofthese: that is, in various social and discursivepractises. In the case of the Rautavaara Monu-ment, the cultural memory makes visible a cer-tain segment of the past and the deceased: thispast is defined by Rautavaara’s sporting achie-vements and good traditional Finnish music.Cultural memory emphasises some aspects ofthe past while others are forgotten. Reminis-cing is closely related to producing identities.The Rautavaara Monument repeats several cli-chés of national imagery and makes nostalgicinterpretations easy. Referring to a certain in-terpretation of national identity the monumentalso forms local identity. Even though the pic-ture or idea of the past is a product formed indiscourses, performances and social practises,it would be over-simplifying to think that thereality or true historical events and the pastproduced in social practises are two distinguis-hable things, of which the former is somehowmore genuine and valuable. The past produc-ed in social practices is real and true for thosewho produce it and those who believe it.

Notes and references

1. E.g. Urry, John (1996). How Societies Remem-ber the Past. In: Sharon Macdonald and GordonFyfe (ed.) Theorizing Museums, pp. 45–65.Blackwell Publishers, Oxford. P. 50; Middleton,David & Edwards, Derek (1990a). Introduction.In: David Middleton & Derek Edwards (ed.)Collective remembering, pp. 1–22. Sage, London.P. 1; Brockmeier, Jens (2002a). Introduction:Searching for Cultural Memory. In: Culture &

Psychology Vol. 8(1), pp. 5–14. Sage, London. P.8.

2. Brockmeier, Jens (2002b). Remembering andForgetting: Narrative as Cultural Memory. In:Culture and Psychology Vol 8(1), pp. 15–43. Sage,London. Pp. 23–24.

3. Brockmeier, Jens & Qi Wang (2002). Auto-biographical Remembering as Cultural Practice:Understanding the Interplay between Memory,Self and Culture. In: Culture and Psychology Vol.8(1), pp. 45–64. Sage, London. P. 60.

4. Brockmeier 2002a: 8; Shi-xu (2002). The Dis-course of Cultural Psychology: Transforming theDiscourses of Self, Memory, Narrative and Cul-ture. In: Culture and Psychology Vol 8(1), pp.65–78. Sage, London. Pp 65–66; Rasmussen, Susan(2002). The Uses of Memory. In: Culture andPsychology Vol. 8(1), pp. 113–129. Sage, London.P. 120.

5. Brockmeier 2002a: 9.6. Brockmeier 2002a: 10; Rasmussen 2002: 122;

Urry 1996: 50.7. Brockmeier 2002a: 8.8. Burke, Peter (1989). History as Social Memory.

In Thomas Butler (ed.) Memory. History, Cultureand the Mind. Basil Blackwell, Oxford (pp. 97–113).

9. See e.g. Brockmeier 2002a: 8; Brockmeier2002b: 26.

10. Forty, Adrian (1999). Introduction. In AdrianForty and Susanne Kühler (ed.) The Art of Forget-ting, pp. 1–17. Berg, Oxford. P. 2.

11. See e.g. texts Forty & Kühler 1999; Lowenthal,David (1985). The Past is a Foreign Country.Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp194–197.

12. Bodnar, John (1992). Remaking America. Pub-lic Memory, Commemoration, and Patriotism inthe Twentieth Century. Princeton University Press,Princeton, pp 12–16.

13. Middleton & Edwards 1990a: 3.

41

Memory as a social and discursive practice in monuments

14. Brockmeier 2002b: 21.15. Brockmeier 2002a: 8; Middleton, David (2002).

Succession and Change in the Socio-cultural Useof Memory: Building-in the Past in Communi-cative Action. In: Culture and Psychology Vol.8(1), pp. 79–95. Sage, London. P. 92.

16. Brockmeier 2002b: 26–27.17. Middleton & Edwards1990a: 5.18. The question of ‘wrong’ memories activates in

processes of the destruction of monuments.Good examples of this can be easily found fromRussia and Eastern European countries duringand after the fall of socialistic regimes at the endof 80s and at the beginning of 90s. See alsoGamboni, Dario (1997). The Destruction of Art.Iconoclasm and Vandalism since the French Revolu-tion. Reaktion Books, London.

19. Rowe, Shawn M. & Wertsch, James V. & Kosy-aeva, Tatyana Y. (2002). Linking Little Narrativesto Big Ones: Narrative and Public Memory inHistory Museums. In: Culture and PsychologyVol. 8(1), pp. 96–112. Sage, London. P. 97.

20. Anderson, Benedick (1991). Imagined Commu-nities. Reflections on the Origin and Spread ofNationalism. Verso, London.P. 6.

21. Hannu Hurme, Rautavaara saa näköispatsaan.Kansan Uutiset 14.1.1999. All quotations arefrom Finnish newspaper articles, magazines andbooks. Translations TL.

22. Brockmeier 2002b: 19.23. Ibid. 21.24. Nora, Pierre (1996a). General Introduction:

Between Memory and History. In: Pierre Nora(ed.) Realms of memory. Rethinking the FrenchPast, pp. 1–20. Columbia University Press, NewYork. P. 8.

25. Brockmeier 2002b: 20.26. Aho, Marko (2002). Iskelmäkuninkaan tuho.

Suomi-iskelmän sortuvat tähdet ja myyttinensankaruus. Acta Electronica Universitatis Tampe-rensis 199. http://acta.uta.fi/pdf/951-44-5433-

2.pdf. pp. 174–176.27. Benjamin, Walter (1936/1992). The Storyteller.

Reflections on the work of Nikolai Leskov. In:Walter Benjamin (Hannah Arendt ed.), Illumina-tions, pp.81–107. FontanaPress, London. P. 86.

28. Salmi, Hannu (2003). “Ajan tomu“ ja “unhonkinos“. Muistamisen tuska sodanjälkeisessä suo-malaisessa iskelmässä. http://www.utu.fi/hum/historia/kh/tunteet/muisto.html (7.2.2003).

29. Mikko Karlsson, Reissumies palasi kotiin. RTUL4/2000.

30. The Rautavaara Monument can also be seen inthe light of the ’hometaking’ of objects. Sörlinhas studied how scientists and collectors havetaken home (by collecting, purchasing, conque-ring, stealing) artefacts, specimens and otheritems during past centuries. As Sörlin writes,these ‘hometaken’ objects may become trophiesand signifiers of the achievements of the home-taking person and of the status on the part of thesponsoring institution, be it a state, academy,museum, library or private person. Sörlin, Sver-ker (1994). Om hemförande. In: Nordisk Museo-logi, nr 1, pp. 53–54. This view could be appliedto the purchasing of monuments. In the case ofthe monument, the hometaken “item” is themeaningful person and his memory in the formof a sculpture.

31. Virtapohja, Kalle (1998). Sankareiden salaisuu-det. Journalistinen draama suomalaista urheilusan-karia synnyttämässä. Atena, Jyväskylä, pp. 151–152.

32. Aila Niinimaa-Keppo, Mitä Tapio Rautavaarasuomalaisille merkitsee? Hymy 11/1995, p. 33.

33. Ibid.34. Hannu Hurme, Rautavaara saa näköispatsaan.

Kansan Uutiset 14.1.1999.35. Arja Nieminen, Tapio Rautavaaralle patsas. Ilta-

Sanomat 1.7.1995.36. Aila Niinimaa-Keppo, Millainen patsas Tapio

Rautavaaralle? Hymy 11/1995, p. 34.

42

Tuuli Lähdesmäki

37. Aila Niinimaa-Keppo, Mitä Tapio Rautavaarasuomalaisille merkitsee? Hymy 11/1995, p.33.

38. Ibid.39. Aapeli Vuoristo (ed.), Suuri Toivelaulukirja 4.

Musiikki Fazer, Helsinki, 1981, p.92. The bookin question is a part of a large series of songbooks consisting famous songs in Finnish.

40. Aila Niinimaa-Keppo, Mitä Tapio Rautavaarasuomalaisille merkitsee? Hymy 11/1995, p.33.

41. Ibid.42. Brockmeier 2002b: 18.43. E.g. Middleton & Edwards 1990a: 10.44. Iggers, George G. (1999). The role of professio-

nal historical scholarship in the creation anddistortion of Memory. In Anne Ollila (ed.) His-torical Perspectives on Memory. Finnish Histori-cal Society, Helsinki (pages 49–67) p. 49.

45. Salmi 2003.46. Aila Niinimaa-Keppo, Näin tehtiin Rautavaara-

monumentti. Ralli 1/2001, p.5.47. Hall, Stuart (1990). Cultural Identity and Dias-

pora. In: Jonathan Rutherford (ed.) Identity,Community, Culture, Difference, pp. 222–237.Lawrence & Wishart, London. Pp. 225–226.

48. Archive of the Tapio Rautavaara Society, State-ment of Helsinki Art Museum, 12.10.1999.

49. Laila Pullinen, Rautavaaran muisto elää Oulun-kylässä. Helsingin Sanomat 27.2.1996.

50. Rasmussen 2002: 121.51. Schwartz, Barry (1990). The Reconstruction of

Abraham Lincoln. In: David Middleton & De-rek Edwards (ed.) Collective remembering, pp.81–107. Sage, London. P. 90.

52. Nora 1996a: 29.53. Nora, Pierre (1996b). From Lieux de mémoire to

Realms of Memory. In: Pierre Nora (ed.) Realms ofmemory. Rethinking the French Past, pp. xv–xxiv.Columbia university Press, New York). P. xvii.

54. Nora 1996a: 7.55. Nora uses the concept to describe the phenome-

na and objects, which are institutionalised to theofficial nationalistic narrative.

56. Arvi Vuorisalo, Oulunkylään on syntynyt helmi.Oulunkyläläinen 19.8.2000.

57. Harri Pirhonen, Tapio Rautavaaran muistomerk-ki on valmis – Kulkurin uni paljastetaan sunnun-taina. Lähilehti 14.6.2000.

M.A. Tuuli Lähdesmäki is a doctoral student in Art His-tory at the Department of Arts and Culture Studies at theUniversity of Jyväskylä. She is researching contemporaryFinnish monuments as discursive and narrative pheno-mena.Adr: Taidehistoria PL 35, 40014 Jyväskylän yliopistoFax: +358 14 260 1461E-mail: [email protected]