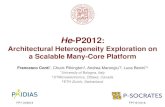

memory

-

Upload

sahilprabhakar -

Category

Documents

-

view

4 -

download

1

description

Transcript of memory

-

MemoryMemorymemory is an organism's ability to store, retain, and recall information and experiences.It is a process which brings the past experiences into a state of consciousness and makes it living

-

MemoryProcess by which information is:AcquiredEncodingStored in the brainStorageLater retrievedRetrievalEventually (possibly) forgotten

-

Definitions of MemoryMemory consists in remembering what has been previously learned Woodworth and Marquis

-

Factors of MemoryLearningMemorising/rememberingRetentionRecallRecognition

-

Favourable conditions of memory/characteristics of good memoryAccurate and quick learningAccurate and durable retentionAccurate and quick recallAccurate and quick recognitionServiceablenessForgetting irrelevant things

-

Types of memoryThree types of memorySensory memoryShort-term memory (STM)Long-term memory (LTM)Can hold vast quantities of information for many years

-

Information-Processing Model of MemoryShort-termmemoryStimulusSensorymemoryLong-termmemoryAttentionEncodingRetrievalForgettingForgettingForgetting

-

Sensory Memory/Immediate memoryStores all the stimuli that register on the sensesLasts up to three secondsTwo typesIconic memoryVisualUsually lasts about 0.3 secondsEchoic memorySensory memory for auditory input that lasts only 2 to 3 seconds

-

Momentary in natureRetentive time is only in secondsEngrams are overwritten by other stimulusEg. Remembering seat no. in cinema hall

-

MemoryShort term memoryactivated memory that holds a few items brieflylook up a phone number, then quickly dial before the information is forgottenLong term memorythe relatively permanent and limitless storehouse of the memory system

-

Short-term MemoryLimited capacityCan hold 7 2 items for about 20 secondsMaintenance rehearsalThe use of repetition to keep info in short-term memory

-

Long-term Memory Working orShort-termMemorySensory

InputSensory MemoryAttentionLong-termmemoryRetrievalOnce information passes from sensory to short-term memory, it can be encoded into long-term memory Encoding

-

Permanent memoryInput is very slowDuration unlimitedCapacity unlimitedRetrieval depends on representation and organizationWe don't have to discard old items to remember new items

-

It is of two typesExplicit memory-long term memory that involves deliberate or conscious recallImplicit memory-knowledge that we are not conscious of recalling , but influences behavior or thought without our awareness

-

Long-term memoryProcedural (Implicit)Memories of behaviors, skills, etc.Demonstrated through behaviorDeclarative (Explicit)Memories of factsEpisodic personal experiences tied to places & timeSemantic general knowledgeSemantic network

-

Factors influencing memoryMeaningfulness and purposefulness of the subject matterAmount of material to be memorizedWill and determination to rememberInterest and attentionRepetition and practiceProvision for change and proper restAssociationGroupingRhythm

-

Part 4Improving Memory

-

Knowledge of Results: Feedback allowing you to check your progress

Recitation: Summarizing aloud while you are learning

Rehearsal: Reviewing information mentally (silently)

Selection: Selecting most important concepts to memorize

Organization: Organizing difficult items into chunks; a type of reorderingSome Ways to Improve Memory

-

Whole Learning: Studying an entire package of information at once, like a poem

Part Learning: Studying subparts of a larger body of information (like text chapters)

Progressive Part Learning: Breaking learning task into a series of short sections

Serial Position Effect: Making most errors while remembering the middle of the list

Overlearning: Studying is continued beyond bare masteryMore Ways to Improve Memory

-

Spaced Practice: Alternating study sessions with brief rest periods

Massed Practice: Studying for long periods without rest periods Lack of sleep decreases retention; sleep aids consolidation Hunger decreases retention

Yet More Ways to Improve Memory

-

Mnemonics: Memory tricks; any kind of memory system or aid Using mental pictures Making things meaningful Making information familiar Forming bizarre, unusual or exaggerated mental associationsA Last Method to Help Memory

*Our memory is the process by which information is retained for later use. The basic process by which information is processed follows this format: information is acquired and encoded, which leads to storage in the brain, which leads to the possibility of later retrieval (though as you know at test time, is not a guarantee), and the possibility of eventually forgetting the information.

Today, cognitive psychologists like to compare the human mind to a computer and memory to an information-processing system. I think you can appreciate the analogy. Your PC acquires (or receives) input from a keyboard or a mouse; it converts the symbols into a special numeric code; it saves the information on a hard drive, CD, or disk; it then retrieves the data from the disk to be displayed on a screen or sends it to a printer. If the computer crashes, if theres not enough space on the disk, if the file was deleted, or if you enter the wrong retrieval command, the information becomes inaccessible, or forgotten.*Using the computer as a model, memory researchers seek to trace the flow of information as it is mentall processed. In this information-processing model, a stimulus that registers on our senses can be remembered only if it 1. Draws attention, which brings it into consciousness; 2. Is encoded, or transferred to storage sites in the brain, and 3. Is retrieved for use at a later time.

Within this information-processing memory approach, three types of memory have been distinguished: sensory, short-term and long-term. Sensory memory stores all stimuli that register on the senses, holding literal copies for a brief moment ranging from a fraction of a second to three seconds. Sensations that do not draw attention tend to vanish, but those we notice are transferred to short-term memory , another temporary storage system that can hold seven or so items of information for about 20 seconds. Although STM fades quickly, information can be held for a longer period of time through repetition and rehearsal. When people talk about attention span, they are referring to short-term memory.

Finally, long-term memory is a somewhat permanent storage system that can hold vast quantities of information for many years. Science writer Isaac Asimov once estimated that LTM takes in a quadrillion separate bits of information in the course of a lifetime. Mathematician John Griffith estimated that, from birth to death, the average person stores five hundred times more information than the Encyclopedia Britannica. When people talk about memory, long-term memory is typically what they have in mind.

Well talk about each of these in a little more detail later on.*Many events register in sensory memory. Those that are noticed are briefly stored in short-term memory; those that are encoded are transferred to a more permanent facility. As shown forgetting may be caused by failures of attention, encoding, or retrieval.

Note, however, that this is only a model and does NOT mean that the brain has three separate storage bins. This is only one view of how memory works. There is a radically different view. Most computers process instructions in fixed sequence, one linear step at a time. In contrast, the human brain performs multiple operations simultaneously, in parallel. Thus, some cognitive psychologists have rejected the information-processing model in favor of parallel-processing models in which knowledge is represented in a web-like network of connections among thousands of interacting processing units all active at once.

The two main questions well be asking ourselves throughout this chapter are: How are memories stored? And to what extend are our memories of the past faithful to reality?*Take a flashlight into a dark room, turn it on, shine it on a wall, and wave it quickly in a circular motion. What do you see? If you twirl it fast enough, the light will appear to leave a glowing trail, and youll see a continuous circle. The reason: Even though the light illuminates only one point in the circle at a time, your visual system stores a snapshot of watch point as you watch the next point. The visual image is called an icon, and the snapshot it stores is called iconic memory.

People typically dont realize that a fleeting mental trace lingers after a stimulus is removed from view. Nor did cognitive psychologists realize it until George Sperlings ingenious series of experiments.*Its important to note that to the extent that one stimulus captures our attention, others may be ignored sometimes with startling effects on memory. For example, research on eyewitness testimony shows that when a criminal displays a weapon, witnesses are less able to identify the culprit than if no weapon is present. Why? One reason is that the witnesss eyes fixate on the weapon, particularly when it comes as a surprise, thereby drawing attention away from the face. To demonstrate, researchers showed subjects slides of a customer who walked up to a bank teller and pulled out either a gun or a checkbook. By recording eye movements, these researchers found that subjects spent more time looking at the gun than at the checkbook. The result: impairment in their ability to identify the criminal in a lineup.

Limited by attentional resources, short-term memory can hold a small number of items. How small an number? The average person can store seven or so items regardless of whether they are numbers, letters, words, or names.

Okay, so short-term memory can accommodate only seven items, and that number may be smaller, but heres the hitch: Although an item may consist of one letter or digit, these items can be grouped into chunks of words, sentences, and large numbers thus enabling us to use our storage capacity more efficiently. The activity we did at the start of this section demonstrates the effects of chunking you were better able to remember more numbers when they were chunked into significant years than when they appeared to be random numbers.

Chunking enables us to improve our short-term memory span by using our capacity more efficiently. You may be limited to seven or so chunks, but you can learn to increase the size of those chunks. Without rehearsal, some researchers find that people can only remember about 4 plus or minus 2 chunks. With rehearsal, were back to the magic seven plus or minus two. But with serious training, people can increase the size of the chunks so that you are remembering large quantities of material. To demonstrate, a group of researchers trained two male university students, both long-distance runners and of average intelligence, for several months. For an hour a day, three or four days a week, these students were asked to recall random strings of numbers. If they recalled a sequence correctly, another digit was added to the next sequence and the task was repeated. If they made a mistake, the number of digits in the next sequence was reduced by one. Before practicing, their memory span was four to seven digits. After six months, they were up to eighty items. In one session, for example, the experimenter read the following numbers in order:

After two minutes of concentration, the subject repeated all seventy-three digits, in groups of three and four. How did he do it? Given no special instructions, the subject developed his own elaborate strategy: he converted the random numbers into ages, dates, and racing times. Thus, 893 became 89.3 (a very old person); 1944 became 1944 (near the end of the second world war); and 3492 became 3 minutes and 49.2 seconds (nearly a worlds record for the mile).*It seems that we have more than one type of long-term memory. Researchers now commonly distinguish two types of memory. One is procedural memory, a know how memory that consists of our stored knowledge of well-learned habits and skills such as how to drive, swim, type, ride a bike, and the tie shoelaces.

The second type is declarative memory, which consists of both semantic memories for facts about the world such as who Michael Jordan is, what a dollar is worth, what you need to access the World Wide Web, and what the word gravity means and episodic memories that we have about ourselves such as who our parents are, where we went to school, and what our favorite movie is. The distinction is important because people with amnesia are often unable to recall declarative memories of facts and events, yet they still retain many of the skills they had learned and committed to procedural memory.

With all thats stored in long-term memory habits, skills, verbal information and knowledge of the words, names, dates, faces, pictures, personal experiences, and the like its amazing that anything can ever be retrieved from this vast warehouse. Surely our knowledge must be organized in memory, perhaps the way books are filed in a library. One popular view is that memories are stored in a complex web of associations, or semantic networks. According to proponents of this view, items in memory are linked together by semantic relationships. When one item is brought to mind, the pathways leading to meaningfully related items are primed thus increasing the likelihood that they too will be retrieved.

A good deal of research supports the notion that memories are stored in semantic networks. When subjects are given a list of sixty words that fall into four categories (animals, professions, names, and fruits) even if the words are presented in a mixed order subjects later tend to recall them in clusters. In other words, retreiving tiger is more likely to trigger ones memory for baboon than for dentist, Jason, or banana.

![[XLS] · Web view005B PC Memory - 4MB 005C PC Memory - 6MB 005D PC Memory - 8MB 005E PC Memory - 10MB 005F PC Memory - 12MB 005G PC Memory - 14MB 005H PC Memory - 16MB 005I PC Memory](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/5ab13df97f8b9ac66c8c4031/xls-view005b-pc-memory-4mb-005c-pc-memory-6mb-005d-pc-memory-8mb-005e-pc.jpg)