Meeting the Challenge of Institutional Fragmentation in ... · climate change and...

Transcript of Meeting the Challenge of Institutional Fragmentation in ... · climate change and...

stem in large part from the fragmentation of decision making withinand across governmental levels, the mismatch of political bound-aries, and the nature of the options for effectively addressing GCC.The paper suggests a conceptual framework for enabling transporta-tion institutions to more effectively and expeditiously respond to thevarious imperatives of GCC.

This paper assumes that the assumptions and conclusions of aTRB special report on the impacts of climate change on transpor-tation (March 2008) (1) are valid and accurate. This paper does notexamine the technical aspects of GCC forecasting, analysis, data, orrelated issues.

IMPACTS OF CLIMATE CHANGE ON TRANSPORTATION

Scientists and others predict that GCC will have widespread effectsacross the entire planet, ranging from rises in sea levels in coastalareas to shifts in climate zones. These shifts may lead to changes inagricultural production and a greater frequency of extreme weatherevents, such as flooding, freezing, and droughts (1). Scientific researchhas established that the principle cause of GCC is steadily increas-ing the emissions of greenhouse gasses (GHGs), primarily carbondioxide, because of the burning of fossil fuels, such as coal and oil, since the mid-19th century and the beginning of the IndustrialRevolution (2).

The potential impacts of GCC on the nation’s transportation systemwere examined in Special Report 290: Potential Impacts of ClimateChange on U.S. Transportation, which TRB published in March 2008.That report found that “The impacts will vary by mode of transporta-tion and region of the country, but they will be widespread and costlyin both human and economic terms and will require significant changesin the planning, design, construction, operation, and maintenance oftransportation systems” (1).

That report also explained that locally controlled land use plan-ning, which is typical throughout the country, has a perspective toolimited to account for the broadly shared risks of climate change.The nature of GCC is truly multidimensional and multijurisdictional,because GCC’s impacts and causes respect no political or geographicboundaries. However, transportation agencies and institutions, whichhave been designed, managed, and funded over a half century to buildfreeways and facilitate the mobility of people and goods, are not well-suited to address the needs related to the mitigation of and adaptationto GCC in an effective manner.

Meeting the Challenge of InstitutionalFragmentation in Addressing ClimateChange in Transportation Planning and Investment

Peter Plumeau and Stephen Lawe

81

Global climate change (GCC) has emerged in recent years as the highest-profile environmental issue of the early 21st century. Transportationinstitutions at all levels of government face significant challenges ineffectively addressing GCC in terms of both the adaptation of the trans-portation system to the impacts of GCC and the mitigation of trans-portation’s contribution to GCC. These challenges stem in large partfrom the fragmentation of decision making within and across govern-mental levels, the consequent mismatch of political boundaries, and thenature of options for effectively addressing GCC. This paper discussesthese challenges and proposes a conceptual framework for rethinkinghow transportation institutions may more effectively address the con-nection between transportation and GCC. It includes an assessment ofthe current state and metropolitan planning activities related to GCCand the perspectives of various planning practitioners from across theUnited States. It also articulates several of the key institutional elementsnecessary for a GCC-responsive transportation agency, including entre-preneurial leadership, an appropriate geographic jurisdiction, a multi-disciplinary organizational structure, appropriately aligned fundingand planning structures, and adequate planning and implementationauthority. Finally, it also offers several suggestions on potential researchneeds associated with climate change and transportation institutionalchange.

Global climate change (GCC) has emerged in recent years as possi-bly the highest-profile environmental issue of the early 21st century.Although there are those who remain skeptical about the very exis-tence of GCC or the influence of human activities on GCC, there canbe little question that GCC is having a significant impact on discus-sions and decisions in multiple policy arenas, including transportationplanning, management, and operations.

This paper is intended to provide context for how and why currenttransportation institutions at all levels of government face significantchallenges in effectively addressing GCC in terms of both the adap-tation of the transportation system to the impacts of GCC and themitigation of transportation’s contribution to GCC. These challenges

P. Plumeau, Resource Systems Group, Inc., 60 Lake Street, Suite 1E, Burlington,VT 05401. S. Lawe, Resource Systems Group, Inc., 55 Railroad Row, White RiverJunction, VT 05001. Corresponding author: P. Plumeau, [email protected].

Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board,No. 2139, Transportation Research Board of the National Academies, Washington,D.C., 2009, pp. 81–87.DOI: 10.3141/2139-10

SYSTEMIC CHALLENGES FACED BYTRANSPORTATION INSTITUTIONS

Transportation institutions will need to overcome several systemicchallenges to develop and administer effective strategies for com-bating GCC. Some are caused by the complex, cross-jurisdictional,and still uncertain nature of GCC. Others derive from more conven-tional organizational fragmentation. Exacerbating the challengespresented by this fragmentation are the aggressive adaptation andmitigation schedules that some people perceive as being required toaddress the problem while certain trends are still reversible.

The causes and impacts of GCC, not unlike those of other air con-taminants (oxides of nitrogen, volatile organic compounds, particu-late matter, etc.), are multijurisdictional. As shown in Figure 1, thereis often little consistency between specific geographic areas emittingsignificant amounts of carbon dioxide (CO2) and established local,metropolitan, and state boundaries (3).

Previous research has identified a general problem concerningthe jurisdictional structure of governance institutions in spatiallyrelated policies because traditional administrative boundaries cause

82 Transportation Research Record 2139

a discontinuity of decision making (4). Also, certain key issues ofnational interest, such as environmental sustainability and climatechange, transcend state and metropolitan boundaries and can be dealtwith only on the large scale. In May 2008, the Brookings Institutionechoed the findings presented in the TRB special report, finding thatthe fragmentation of federal transportation, housing, energy, andenvironmental policies impedes action in addressing GCC at themetropolitan level (5).

Therefore, to have a real potential to address the mitigation ofand adaptation to GCC in an effective and efficient manner, trans-portation organizations may need to adopt some of the same strate-gies employed in the Clean Air Act, such as regional compacts thatspan strict political jurisdiction boundaries. In general, the goalshould be to move toward geographic purviews that are scaled tothe scope of the problem and that are not constrained by politicalboundaries that have no relevance to the problem. At the same time,because understanding of GCC continues to evolve and change, itis important that institutional arrangements be able to move rela-tively quickly and not be mired in the details of cross-jurisdictionalnegotiation.

FIGURE 1 Geography of carbon dioxide emissions in the continental United States, 2002 (3).

STATE AND METROPOLITAN ACTIONS

As of August 2006, more than half of the U.S. states were activelyinvolved in planning for climate change, with one or more policiesthat promise to significantly reduce their GHG emissions being for-mulated (6). However, there are significant inconsistencies in thepolicies, goals, and action plans used to address the mitigation ofand adaptation to GCC among the states and metropolitan regions.For example, recent research conducted by various entities on behalfof NCHRP found that state goals for reducing GHG emission fromthe transportation sector range dramatically. As shown in Table 1,of 17 state plans examined, the expected proportion of transporta-tion-related GHG reductions that will come from the use of smartgrowth and transit strategies ranges from 64% (Washington) to 6%(Oregon) (7 ).

Similarly, the handful of metropolitan planning organizations(MPOs) that have begun to address GCC in their plans and planningprocesses have used a wide range of approaches. For example,although the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governmentsissued a major, multidimensional draft Climate Change Report forthe entire metropolitan region in July 2008 (8), only about 10 MPOsnationwide attempted to quantify the GHG emissions associatedwith their long-range transportation plans as of April 2008 (9).

Furthermore, among both departments of transportation (DOTs)and MPOs, mitigating responses to climate change are much betterdeveloped than adaptive responses. Although some agencies at boththe state and the MPO levels are developing specific strategies toanalyze and reduce GHG emissions, adaptive responses are typi-cally just acknowledgments of risk or suggestions for research (9).Recent research suggests that even in areas of the country especiallyvulnerable to risks to the infrastructure because of rises in sea lev-els and other climate change-induced impacts, most transportationagencies do not (or have only just recently begun to) consider cli-

Plumeau and Lawe 83

mate change projections in their long-range plans, infrastructuredesign, or siting decisions (10).

It is obvious that absent a clear national policy or goals for address-ing climate change, many subnational jurisdictions have taken itupon themselves to try to develop their own strategies and policies.However, the lack of a national framework or common goals acrossmajor parts of the country has apparently precipitated a situation inwhich fragmentation rather than coherence and consistency is theprincipal theme.

PERSPECTIVES FROM RECENTTRANSPORTATION INSTITUTION DIALOGUES

The professionals charged with analyzing the issues and developingthe options related to GCC for policy makers bring a critical practi-tioner’s perspective to understanding the challenges that transportationagencies face. It is therefore important to consider these perspectivesas approaches to institutional change are explored. Between Marchand October 2008, a series of three peer workshops that engaged seniorofficials of DOTs and MPOs from across the nation, as well asobservers from the federal government and other entities, providedinsight into some of these perspectives.

The workshops, sponsored by FHWA, explored the issues thattransportation agencies face in attempting to integrate GCC into thetransportation planning process (11). The workshop participantsarticulated several key themes:

• Climate change needs to become a national planning priority.• The public and policy makers need to be fully educated about

climate change and transportation’s relationship to it.• Planning for climate change in transportation needs to be per-

formance based.• The relationship of land use patterns to climate change needs

to be clearly articulated.• Continuous communication and information sharing among

planning partners should be facilitated.

Making Climate Change a National Planning Priority

Without clear national goals or priorities regarding climate change,it is difficult for transportation agencies to establish climate change-related planning priorities that are compelling to policy makers andthe public. At the same time, any federal policy actions should allowstate, regional, and local transportation institutions to have flexibil-ity in how they respond to federal goals and priorities to account forlocal conditions.

Educating the Public and Policy Makers about Climate Change and Transportation

Educating the public and policy makers about climate change is amajor challenge because of the difficulty associated with translatingcomplex and sometimes obscure information about climate changeinto tangible, meaningful, and compelling stories. It will be neces-sary to help people understand how their individual behaviors con-tribute to climate change as well as the looming consequences ofclimate change for them as individuals, their communities, and the

TABLE 1 Selected Statewide Climate Change Action Plans andProportion of Transportation-Related GHG Mitigation Attributableto Different Transportation Actions (7 )

Vehicle Low Carbon Smart Growth OtherState Year (%) Fuels (%) and Transit (%) (%)

Wash. 2020 8 23 64 5

Vt. 2028 21 14 49 17

Md. 2025 24 12 45 20

N.C. 2020 35 12 38 15

Calif. 2020 54 6 38 2

R.I. 2020 46 10 31 14

S.C. 2020 14 55 29 1

N.Y. 2020 59 11 27 4

Minn. 2025 15 35 25 25

Ariz. 2020 40 7 25 28

Colo. 2020 40 26 22 13

Me. 2020 53 25 21 1

Pa. 2025 45 36 18 0

N.M. 2020 31 21 16 31

Conn. 2020 51 38 8 2

Mont. 2020 61 24 8 7

Ore. 2025 80 14 6 0

nation. To have an appreciable positive impact on society, this willlikely require concerted and sustained education campaigns overmany years.

Planning for Climate Change in TransportationNeeds to Be Performance Based

In a world with limited resources and growing concern about theimpacts of climate change, the impacts of transportation plans andinvestments must be understood. The application of a performancebasis to the mitigation of and planning for adaptation to climatechange is thus important for ensuring that the actions that are takenare as beneficial as possible. The workshop participants believedthat this will likely require shoring up and improving traditional ana-lytical tools and methods to ensure that transportation planning andpriority setting are credible and effective.

Articulating the Relationship of Land UsePatterns to Climate Change

The workshop participants generally agreed that making fundamen-tal changes in how land use and transportation are planned and inte-grated are essential to both mitigating the effects of and adapting toclimate change. However, because of the great variation in land useplanning and decision making across municipalities and the nation,it may be exceedingly difficult to develop any workable federal laws,policies, or regulations to require more explicit linking of land useand transportation through the mandated planning process. It wassuggested that the federal government should put forth major financialincentives to facilitate more effective land use planning.

Need for Continuous Communication andInformation Sharing Among Planning Partners

Because GCC is a dynamic and complex issue, opportunities to shareinformation across MPOs, state DOTs, localities, and the federalgovernment need to be made as frequent and accessible as possible.Continuous communication and information sharing among peerand partner agencies across the nation are particularly important inlight of the interjurisdictional nature of GCC.

OVERCOMING INSTITUTIONALFRAGMENTATION TO ADDRESS CLIMATE CHANGE IN TRANSPORTATIONPLANNING AND INVESTMENT

Leadership as a Precursor to Effectiveness

Planners are accustomed to dealing with linear projections and lin-ear change. However, nonlinear change, such as that presented bythe dynamic and multidimensional issue of global climate change,is difficult for established institutions to deal with successfully (andmay even be considered a threat to the established order) (1). Over-coming the obstacle of institutional inertia will require a variety ofchanges, including, perhaps most importantly, leadership.

In A Transportation Executive’s Guide to Organizational Improve-ment, AASHTO cited “leadership” at the chief executive officer levelas a major factor in the success of transportation agencies (in this case,

84 Transportation Research Record 2139

state DOTs) that proactively pursue organizational excellence. Amongthe qualities of the leaders cited were that they are willing to try newthings and show commitment to creating positive change and leavingan organization that would continue to be successful over time (12).Similarly, research on the success of MPOs across the nation in meet-ing regional transportation needs has shown that effective leadershipis an element critical to that success. In 2002, a congressional studynoted that the most successful MPOs appear to have leaders withthe ability to achieve progressive collaboration and build consensusbetween individuals with diverse interests and to fashion regionalsolutions to common problems (13). Furthermore, in 2005, the feder-ally sponsored Colloquy on the Coming Transformation of Travel,which considered the expertise and opinions of an expert panel drawnfrom universities, consulting firms, governmental agencies, and else-where, found that “visionary leadership” would be a necessary ele-ment of transportation planning entities in the future. By nurturingsuch leadership, transportation agencies can allow short-term localdecisions to be consistent with long-term strategic goals (14).

Aligning Approaches with Challenges to Facilitate Transportation Institution Effectiveness

Effective leadership would therefore seem to be an important pre-cursor to or at least a necessary element of reengineering transporta-tion institutions to become effective parts of the solution to theclimate change challenge. However, the climate change issue bearsmany of the hallmarks of a “wicked problem.” Wicked problemscannot be solved in a traditional linear fashion, because the problemdefinition evolves as new possible solutions are considered or imple-mented. Wicked problems always occur in a social context: thewickedness of the problem reflects the diversity among its stake-holders. It is the social complexity and not the technical complexityof these problems that overwhelms most current problem-solvingand project management approaches (15).

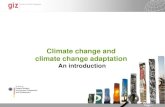

The complexity of the GCC problem requires radically new insti-tutional arrangements and structures. As shown in Figure 2, institu-tional approaches, which are currently geographically and topicallyfragmented, need to become much more adequately aligned withthe multijurisdictional and multidisciplinary nature of the climatechange problem. In other words, addressing climate change-relatedchallenges requires multidimensional actions and multidimensionalinstitutions or institutional arrangements.

Leadership will be critical to promoting the actions that facilitate thetransformation of these institutions into climate change-responsiveentities. Reengineering the following four elements of transportationinstitutions will enable more expeditious and effective responses tothe challenges of climate change.

Appropriate Geographic Jurisdiction

GCC’s causes and impacts are multijurisdictional. Therefore, tohave a real potential to address the mitigation of and adaptation toGCC in an effective and efficient manner, transportation organiza-tions need to move toward geographic purviews that are scaled tothe scope of the problem and not be constrained by political bound-aries that have no relevance to the problem. There is also ample pre-cedent in American federalism for states to work cooperatively oncommon concerns and even formalize regional approaches involv-ing two or more mutually significant issues. Some regional strate-

gies take a permanent structure, such as interstate compacts, whichinvolve a formal agreement ratified by participating states and ulti-mately the U.S. Congress. These have been used extensively amongstates that share responsibility for an ecosystem or common bound-ary. Other strategies may entail the establishment of multistate orga-nizations or commissions to address particular issues, commonlywith some degree of active federal support (6).

As state climate change-related policies proliferate and diffuse,certain clusters of states may become, in practice, regions even inthe absence of formal agreements or any constructive engagementfrom federal authorities. One such example is the Regional Green-house Gas Initiative (RGGI), which is a cooperative effort by ninenortheast and mid-Atlantic states to discuss the design of a regionalcap-and-trade program initially covering carbon dioxide emissionsfrom power plants in the region. Initiated by New York State in2003, RGGI is considering the inclusion of other sources of GHGemissions and GHGs other than CO2 (16). Similarly, the WesternClimate Initiative (WCI), launched in February 2007, is a collabo-ration of seven U.S. governors and four Canadian provincial pre-miers. The five original member states created WCI to identify,evaluate, and implement collective and cooperative ways to reduceGHGs in the region, focusing on a market-based cap-and-trade sys-tem. WCI currently plans to include transportation-generated GHGsin its cap-and-trade program (17 ).

Multidisciplinary Organizational Structure

As highlighted throughout this paper, GCC is a highly complexissue. Although the transportation sector cannot and should not be

Plumeau and Lawe 85

the primary respondent to the GCC challenge, it is important toensure that any actions taken by transportation agencies are notundermined by a lack of coordination and collaboration across dis-ciplines, both within the transportation realm (planning, funding,design, operations, maintenance) and between transportation andkey related realms (land use, urban design, economic development,etc.). For example, transportation agencies at various levels willneed to partner to determine the vulnerabilities of their transporta-tion systems to rising sea levels, storm surges, more severe storms,higher temperatures, and, in some areas, drought. Such determina-tions will require the use of a variety of technical and policy toolsthat speak to different institutions’ expertise and interests. Similarly,many of the state climate change action plans assume aggressiveland use and transportation strategies, including significant reduc-tions in growth in the number of vehicle miles traveled (VMT) or, inat least one case, significant reductions in per capita VMT. Achiev-ing these goals will require substantial rethinking of whether andhow states, MPOs, other regional bodies, and localities can workcooperatively on the traditionally thorny issue of land use controland decision making. It is therefore important that transportationagencies move to establish effective and enforceable pacts withother key agencies within and across jurisdictional levels to maxi-mize the effectiveness of actions related to GCC and minimize therisk of implementation of counterproductive plans and initiatives.

Alignment of Funding and Planning Structures

GCC presents an opportunity for grantor agencies and entities thatauthorize transportation funding to seek accountability from grantees

TODAY

Multi-jurisdictional

Local

Fragmented Integrated

POSSIBLE APPROACHESGeography & Disciplines

Simple

COMPLEXITYOF PROBLEM

Multi-disciplinary

Less Effe

ctive

More E

ffectiv

e

SCALE OFPROBLEM

OptimumAlignment

forAddressing

GCC

FIGURE 2 Framework for aligning institutional approaches with challenges of GCC.

related to effective adaptation to and mitigation of GCC. In addition,funding may be an important avenue by which grantors and autho-rizers could incentivize the more widespread and effective integra-tion of transportation, land use, and urban form. For example, afterthe adoption of targets (whether they are self-established or pro-mulgated under some future federal action), states could earmarkand distribute at least a portion of transportation and other relatedinfrastructure funds on the basis of local performance in meetingGHG and VMT reduction targets (18).

Another option that could be considered at the substate and met-ropolitan levels is tying federal funding eligibility to a land use con-formity process that helps ensure that official local land use plansand regional and metropolitan transportation plans are mutually sup-portive and facilitate reductions in GHG emissions. Another direc-tion might be to allow or expand the use of public funds throughcompetitive grants to encourage private developers and landownersto design communities that help achieve GHG reduction goals.

Adequate Planning and Implementation Authority

Although it may be one of the most challenging issues to resolve, it isapparent that the authority to implement or enforce transportationplans must be better matched with their responsibilities for puttingforth plans. This ability is a critical element of making the strongerconnections between transportation and land use development that arehighlighted in many state GCC-related action plans. Several entitiesthat could be conceptual models for bridging planning and implemen-tation roles currently exist. These include the Regional TransportationCommission of Southern Nevada, which is the MPO and transit, free-way, and arterial operator for the Las Vegas, Nevada, region and theTransnet program under the San Diego (California) Association ofGovernments, which is authorized to collect sales taxes to fund andoperate freeways, transit, and local roadways.

It may also be instructive to consider examples of cross-jurisdic-tional transportation planning and operating entities from othercountries as potential models for the United States to consider. Forexample, in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, the South CoastBritish Columbia Transportation Authority, known as TransLink,has jurisdiction over the planning, funding (including taxing author-ity), construction, and operations of transit; ferries; and 12,000 miof regional, urban, and suburban roads. Since 2007, TransLink hasalso had the authority to generate revenue by controlling the devel-opment of land near and around transit stations, including overridingmunicipal land use planning, thus facilitating a level of coordinatedtransportation–land use development much greater than that whichis typical in the United States (19).

SUGGESTED RESEARCH NEEDS

This paper has suggested a variety of potential policy and institu-tional changes that could be made to improve transportation institu-tions’ effectiveness in addressing climate change. In several of theareas discussed, there is a need for continued or more in-depthresearch in certain topics, including the following:

• How can transportation planning and design processes bereengineered to be conducted within a multidisciplinary set of per-spectives, particularly perspectives not traditionally well-engagedin the front end of the transportation planning process (e.g., housing,natural resources, and community development)?

86 Transportation Research Record 2139

• What is the appropriate geographic scale that planning agen-cies should cover to follow travel and settlement patterns more log-ically, maximizing their ability to facilitate positive change? Canagencies and governments move past the limiting nature of tradi-tional political boundaries? How should this issue be addressed innonmetropolitan regions?

• What are the appropriate transportation performance measuresrelated to the mitigation of and adaptation to climate change? At whatgeographic scale should performance be measured and assessed?

• Do options for using public funds to incentivize more inte-grated transportation and land use planning and implementation in both the public and the private sectors exist? Do their potentialclimate change-related benefits justify their costs?

• What are appropriate models for use in the design of agencieswith integrated planning, funding, and operating authority at the met-ropolitan or regional level? What are the barriers to this integration,and how might they be overcome?

• What are the most effective ways to educate the public and pol-icy makers about the transportation–climate change connection?What tools and techniques are available or needed to help achieve ageneral national understanding of the problem?

CONCLUSION

Nobody—no matter who we are or what position and power we hold—can choose the future. It will be forged by the individual and collec-tive decisions and actions of thousands of organizations and millionsof engaged citizens around the world. Yet the wiser our choices,informed by thoughtful appreciation of the drivers of change and thenew challenges and opportunities that may await us, the better. (20)

The wicked problem that is the fragmentation of the nation’s trans-portation planning, decision-making, and operating institutionshas the potential to make the mitigation of and adaptation to globalclimate change difficult or even more complex. Without highlycoordinated and intelligently sequenced policies, plans, and actions,climate change will likely continue to be addressed through a grow-ing patchwork of regional, state, and local initiatives. Because thecauses and impacts of climate change respect no artificial politi-cal boundaries, an uncoordinated approach is highly inefficientand unlikely to help the nation meet any national goals for GHGreductions that are put forth in the near future as different localesseek to use different strategies and targets. Furthermore, in an eraof increasingly constrained funding and resources for needed trans-portation improvements (operational and infrastructural improve-ments), it is in the best interests of the transportation communityand the nation to begin the critical process of rethinking trans-portation institutions so that they may address climate change andthereby facilitate the nation’s mobility and economic vitality wellinto the future.

REFERENCES

1. Special Report 290: Potential Impacts of Climate Change on U.S.Transportation. Transportation Research Board of the National Acade-mies, Washington, D.C., 2008.

2. Pew Center on Global Climate Change. Climate Change 101: The Sci-ence and Impacts. www.pewclimate.org/global-warming-basics/climate_change_101. Accessed June 15, 2008.

3. Project Vulcan Website. Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences,Purdue University. www.purdue.edu/eas/carbon/vulcan/plots.html.Accessed June 15, 2009.

4. Macario, R. Restructuring, Regulation and Institutional Design: A FitnessProblem. In Competition and Ownership in Land Passenger Transport:Selected Papers from the 9th International Conference (Thredbo 9), Lis-bon, Portugal, Sept. 2005. Elsevier Ltd., Oxford, United Kingdom, 2007.

5. Brown, M., F. Southworth, and A. Sarzynski. Shrinking the CarbonFootprint of Metropolitan America. Brookings Institution, Washington,D.C., May 2008, p. 1.

6. Rabe, B. Second Generation Climate Policies in the American States:Proliferation, Diffusion, and Regionalization. Brookings Institution,Washington, D.C., Aug. 2006, pp. 5–8.

7. NCHRP 20-24(59): Strategies for Reducing the Impacts of SurfaceTransportation on Global Climate Change. Preliminary Data. ParsonsBrinckerhoff, Washington, D.C., June 2008.

8. National Capital Region Climate Change Report. Review Draft. Metro-politan Washington Council of Governments, Washington, D.C., July2008.

9. ICF International. Integrating Climate Change into the TransportationPlanning Process, Draft Final Report. FHWA, U.S. Department ofTransportation, June 2008, pp. 14–20.

10. Potter, J. R., V. R. Burkett, and M. J. Savonis (eds.). Executive Summary.In Impacts of Climate Change and Variability on Transportation Systemsand Infrastructure: Gulf Coast Study, Phase I. A Report by the U.S. Cli-mate Change Science Program and the Subcommittee on Global ChangeResearch. U.S. Department of Transportation, 2008.

11. Resource Systems Group, Inc. Summary Report: MPO Peer Workshopon Planning for Climate Change. FHWA, U.S. Department of Trans-portation, March 2008, pp. 12–16.

Plumeau and Lawe 87

12. A Transportation Executive’s Guide to Organizational Improvement.AASHTO, Washington, D.C., 2007, pp. 11–13.

13. Goetz, A., P. S. Dempsey, and C. Larson. Metropolitan Planning Orga-nizations: Findings and Recommendations for Improving Transporta-tion Planning. Publius: The Journal of Federalism, Vol. 32, No. 1, 2002,pp. 87–105.

14. Colloquy on the Coming Transformation of Travel. New York StateMetropolitan Planning Organization Association, Volpe NationalTransportation Systems Center, U.S. Department of Transportation,2006, pp. 8–9.

15. Wicked Problems. CogNexus Institute. www.cognexus.org/id42.htm.Accessed Oct. 12, 2008.

16. Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative. www.rggi.org/about.htm. AccessedJuly 8, 2008.

17. Western Climate Initiative. www.westernclimateinitiative.org. AccessedJuly 8, 2008.

18. Ewing, R., K. Bartholomew, S. Winkelman, J. Walters, and D. Chen.Growing Cooler: The Evidence on Urban Development and ClimateChange. Urban Land Institute, Washington, D.C., 2008, p. 1316.

19. Major TransLink Overhaul Going Ahead. CBC British Columbia,March 7, 2007. www.cbc.ca/canada/british-columbia/story/2007/03/08/bc-translink.html. Accessed June 20, 2008.

20. Kelly, E. Powerful Times: Rising to the Challenge of Our UncertainWorld. Wharton School Publishing, Philadelphia, Pa., 2006, p. 245.

The Strategic Management Committee sponsored publication of this paper.