MCN 2 Wulfstan's Voyage in IJNA 39, 2010

Click here to load reader

-

Upload

anton-englert -

Category

Documents

-

view

152 -

download

1

Transcript of MCN 2 Wulfstan's Voyage in IJNA 39, 2010

Kibbutz Ginosar, where it underwent conservationand is currently on display. Addressed more to ageneral audience than to the professional archaeolo-gist, it is a ‘whodunit’ work for which the archaeologyof the boat, Biblical gospels, and other historicalsources, including Mark Twain’s writings of hisvoyages on the Sea of Galilee, provide an engagingcontext. Wachsmann argues that the Sea of GalileeBoat was of the same type mentioned in the Gospelsand employed by the disciples of Jesus, as well as thesame type of boat used by the Jews to fight the Romansduring the battle of Migdal. While there is no archaeo-logical evidence to support this assertion, Wachsmannmakes the point that the Gospels are records of theexceptional and on the whole omit the mundane.Wachsmann also asserts that the Sea of Galilee Boat,a type of vessel commonly used in fishing activities onthe Sea of Galilee, was probably the largest type ofsuch boat found on the lake at that time.

The book lays out the exceptional series of eventsengendered by the boat’s discovery, with machine-guns,military helicopters, and political/religious conflictall making an appearance. For example, Wachsmanndetails how he and his team arrived on site one day tofind people from the agricultural group Moshav Migdalguarding the site with loaded guns, believing that thesite was political gold. They obviously underestimatedthe delicate nature of excavation and conservationrequired before the boat could be put on display. Wach-smann uses the engrossing technique of alternatingchapters between discussions of the archaeologicalactivities taking place around the boat, and detailingthe historical context from which the boat sprang. Inthis way he brings the reader in and out of the past,showing how the past both contextualizes and informscurrent activities and regional social/political dynamics.Throughout the book, Wachsmann’s thoughtful styleof writing propels the reader forward, while his use ofwordplay adds to the work’s humour.

Wachsmann makes the point that much ofarchaeology—rescue archaeology in particular—isimprovisational, and the Sea of Galilee Boat excava-tions certainly demonstrate this. Probably the mosthumorous example of such improvisation relatesan instance when the conservation tank became abreeding-pond for some mosquito larvae. After con-sidering the use of several different types of pesticides,and fearing that these might have adverse affects onthe conservation process, Moshe came up with theecologically-correct answer by stocking the pool withgoldfish, which ‘merrily gobbled’ every last squirminglarva.

On more of a technical note, the book is exception-ally comprehensive, including a discussion of the 12different types of wood used in the boat’s construction,the anchors it may have carried, the size of its crew (atleast five— four oarsman and a captain), and the typeof sail used to propel the boat (a single square-sail on amast supported by fore-and-aft stays). It also contains

a glossary for those who are not familiar with nauticalterms. The publication is well served with black-and-white line drawings helpfully illustrating events andconcepts in the text. It is error-free, with the exceptionof what seems to be a printing mistake—a sentenceleft out between pages 279 and 280. Additionally, thepaperback binding is of rather poor quality. Pagesbegan to fall out of the book half-way through readingit.

The book’s moral seems to be that archaeology is notabout finding gold, which many of the locals believedthe boat to have carried, but rather that a really ‘oldboat’ can be a treasure to many—to archaeologists,to researchers and to political and religious groups,depending on how the site is treated and interpreted.In this respect Wachsmann should be applauded forexploring the many avenues of interpretation that couldbe applied to the Sea of Galilee Boat. His book hasbrought its archaeology to the people in a fun andwell-informed way.

CLAIRE P. DAPPERTWashington DC

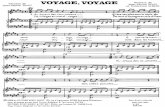

Wulfstan’s Voyage: the Baltic Sea regionin the Early Viking Age as seenfrom shipboard(Maritime Culture of the North 2)

ANTON ENGLERT and ATHENA TRAKADAS(eds)

347 pp., c.150 illustrations with many coloured maps,10 tables

Viking Ship Museum, Roskilde, DK-4000, availablevia Oxbow Books, 10 Hythe Bridge Street, OxfordOX1 2EW, UK, 2009, £53 (hbk), ISBN 978–8785180568

This is the eagerly-awaited companion volume toOhthere’s Voyages (2007) (reviewed in 37.1 (2008),194–5), and as such the second book in the RoskildeViking Ship Museum’s new monograph series ‘Mari-time Culture of the North’. It is a collection of essaysdiscussing matters arising from the second part of apassage added to the geographical section of the OldEnglish translation of Orosius’s Historiae, the firstpart of which is the subject of the previous volume.Although the text on Wulfstan is much shorter thanthat on Ohthere, it has nonetheless produced an essaycollection almost twice as long (though fortunately nottwice as expensive).

While the extreme parts of Ohthere’s and Wulfstan’svoyages are far apart, the accounts overlap in Danishwaters, and especially in Hedeby, the finishing point ofOhthere’s voyages and the starting point of Wulfstan’s.Consequently, some of what is said in the new volumeis also of interest to students of the Ohthere text, most

REVIEWS

© 2010 The Authors. Journal Compilation © 2010 The Nautical Archaeology Society 203

notably a long and detailed discussion of 9th-centuryHedeby itself. With this in mind, it is tempting toregard these two volumes as parts of the same workin much the same way that the Old English voyageaccounts are ultimately part of the same text. They canbe enjoyed separately, but are best read together.

The volume starts with a close look at the OldEnglish text itself. Fortunately, although the insertioninto Orosius (both Ohthere’s and Wulfstan’s reports)was already edited in full in the previous volume, thepassage concerning Wulfstan’s voyage is here repeated,first in facsimile, then in both edited Old Englishand translation, along with some relevant extractsfrom Ohthere’s report and with commentary on somenames. This is followed by a discussion of the languageof the Wulfstan passage in particular (by the text’seditor, J. Bately), of Wulfstan’s identity (by J. Jesch)and of the text’s place in contemporary geographyand travel literature (in two essays by R. Simek andP. Urbanczyk).

The second section (also the longest) is concernedwith the geography and political make-up of the south-ern Baltic Sea in the 9th century. The section beginswith discussions of the ethnogenesis and socio-politicalstructures of the peoples inhabiting the region, Baltic,Slavic and Scandinavian (by C. Lübke with a note byP. Urbanczyk, and by W. Duczko, respectively). Afterthis, S. M. Sindbæk discusses the nature of long-distance traffic and the reasons why some places arementioned in the account while others, despite beingwell-known archaeologically, are not. The next sevenessays provide in-depth treatment of the harbours andtrading places along Wulfstan’s route. In recognitionof the recurring argument that Wulfstan’s report maynot be the account of a single voyage, many places arediscussed which the Old English text only mentionsin passing, if at all. The discussions start at Hedeby(V. Hilberg) and go east from there, taking in theDanish archipelago and Skåne (two essays by J.Callmer and J. Ulriksen), Bornholm (A. Nørgård Jør-gensen), the mainland coast of modern-day Germany(H. Jöns), the destination port of Truso on the Vistula(M. F. Jagodzinski), and finally the Baltic areas, forwhich Truso provided the gateway (V. Žulkus andM. Bartašius, in German).

The third section is dedicated to seafaring. It openswith an exposition on transport zones, their signifi-cance for shipping routes and vessel types, placingWulfstan’s journey in the context of this theoreticalapproach (C. Westerdahl). This is followed by a paperintroducing the Cosmography of Aethicus Isther, an8th-century Latin text, which appears to contain anec-dotal information on the Baltic Sea area, but is rarelystudied in this context. It is particularly interestingin its reference to ship-types, using a number of Latinwords not known from classical and Mediterraneantexts. With a view to identifying the kind of vesselWulfstan may have used, O. Crumlin-Pedersen goes onto discuss the boats in use in the region at the time (and

also slightly later). He begins by giving an overview ofarchaeological finds in turn from Denmark, SouthernSweden and Norway, from the Slavic coast, and fromfurther east as well as Central Sweden, going on tocompare and contrast this with the evidence from theNorth Sea catchment, before asking whether shipsmight have been brought east from the North Sea. A.Englert (one of the editors of this volume) and W.Ossowski then present the results of a 2004 trial voyagefrom Hedeby to Gdansk using the replica of the 11th-century trading vessel Skuldelev 1, analysing the crew’sobservations as well as openly discussing the reasonsand implications of using a much later ship. Naviga-tion and seamanship are the subject of two furtheressays. The first draws attention to our lack of knowl-edge of the potentially quite different geography ofparts of the Baltic Sea coast at the time and its impli-cations for studying methods of terrestrial navigation(S. McGrail). The second, much longer, one uses awide range of ethnographic, experimental and theoreti-cal material to show how much can be deduced aboutancient navigation all the same (G. Indruszewski andJ. Godal, with M. Vinner).

A shorter final section discusses voyaging in thesouthern Baltic Sea at Wulfstan’s time, its purposesand dangers. It starts out with an essay about tradein the Baltic Sea area, concentrating on coinage,exchange values and their implications for the develop-ment of trading places (H. Steuer). This is followedby a pair of essays discussing the Christian missions.The first of these deals with south-east Scandinavia(J. Staecker), opening with the Vita Anskarii, whichcontains the other contemporary report of a voyagein the region; the second goes on to show evidencefrom the Slavic coast (F. Biermann). J. Bill wraps up thesection with a discussion of piracy and maritime safety,the extent of the risk and the measures taken to avoid it.The volume closes with a summary by M. Müller-Wille.

The result of these efforts is a thorough interdisci-plinary study of the southern Baltic Sea in Wulfstan’stime, reaching far beyond the limitations of the shortOld English texts. It is also an impressive exercise ininternational co-operation, with the participation ofscholars from all the modern countries touched uponby Wulfstan’s account, and others from as far afield asEngland (his probable home) and Lithuania (withinreach of his destination).

Like the Ohthere volume, and indeed as usual withVSM publications, the book is beautifully producedand richly illustrated (partly in colour), and it retainsthe tried-and-tested layout with two columns of textplus an inner margin for notes and captions. The maindifference is the decision to retain each article’s sepa-rate bibliography, rather than integrating them into asingle bibliography at the end; a feature which hadseemed quite useful in Ohthere’s Voyages. The indexhas added a useful category on ship terms (besidesnames and general information), but again is rathershort. These, however, are minor points which may

NAUTICAL ARCHAEOLOGY, 39.1

204 © 2010 The Authors. Journal Compilation © 2010 The Nautical Archaeology Society

well fall within the realm of personal preference. Theyare far outweighed by the value of the content forscholars of the Baltic Sea region in the Early VikingAge, in any discipline.

KATRIN THIEROxford, England

Sutton Hoo and its LandscapeTOM WILLIAMSON

154 pp., 69 illustrations and maps, some colour

Windgather Press, 10 Hythe Bridge Street, OxfordOX1 2EW, UK, 2008, £20 (sbk), ISBN 948–1905119257

Within a mere 144 pages of text the author, Professorof English Landscape History at the University ofEast Anglia, has included a most useful synthesis ofresearch on Suffolk’s famous Anglo-Saxon ship-burialsite. In recent years Sutton Hoo has attracted aplethora of publications, and Tom Williamson deftlyextracts the key themes and hypotheses for us. Heis particularly keen to counter phenomenologicalapproaches which ‘if adopted uncritically, can easilybecome no more than exercises in misinformed specu-lation’. He hopes that the central section of his bookwill at least represent an exercise in partially-informedspeculation. Having counselled caution throughout, hesets aside one chapter in which he allows himself topropound some theories of his own, demolishing a fewothers in the process.

Elucidated by a series of coloured maps, the meat ofthe text is a careful study of the area surroundingSutton Hoo covered in a field-walking survey. Thewoodland today is much more extensive than in thepast. Having demonstrated that the enclosures, settle-ments and tree-cover were largely influenced by thepoor soils of much of the Sandlings peninsula,Williamson sets out to answer the question why theburial mounds were located there. This task takes himbeyond the immediate vicinity to map the countrywidedistribution of significant artefacts and place-names.He first defines the extent of Anglian settlement and,secondly, provides possible reasons for a power-base tohave been located here at its south-eastern tip.

For readers of this Journal the relevance of thebook does not lie in Williamson’s observations on theship buried beneath the largest mound—he describesit as having had a ‘steering paddle’ rather than thequarter-rudder evinced by the shape of its 24thrib—but by his study of the eastern bank of the RiverDeben on which the site lies. Nowhere is the termused, but clearly a maritime cultural landscape isbeing defined de novo by a land-based scholar, ‘trav-elling by land along the coastline these great inter-ruptions in an otherwise topographically uneventfulcountryside thus make a profound moving impact on

the observer: and it is hard to believe they would notalways have done so.’

Lacking the concept, the author has bisected themaritime cultural landscape of the Deben: the westbank is ignored. As a result two places, candidates forimportant contemporary settlement and which possessfertile soils, rising ground and now filled-in creeks, arenot discussed. These are Melton, which lies oppositethe burial-site and produced a sadly unprovenanced6th-7th-century gold-and-garnet mount, and thestrand of Woodbridge slightly downstream of it. Thisomission leads Williamson solely to conclude from hiscareful consideration of restricted distant visibility that‘the view of the Sutton Hoo cemetery from the riverwas thus less important than the view of the river fromthe cemetery’. Despite its limitations from a maritimearchaeologist’s viewpoint, the book can be recom-mended as a succinct context for the ships buried atSutton Hoo.

VALERIE FENWICKBlaxhall, Suffolk, England

The ‘Old Ships’ of the ‘New Gate’, vol. 1Yenikapı’nın Eski Gemileri, Cilt I(parallel English/Turkish texts)

UFUK KOCABAS (ed.) with nine Contributors

323 pp., 232 colour illustrations, 15 line drawings, 35tables, 4 maps

Ege Yayinlari/Zero Books Ltd, Abdullah Sokak 17,Taksum, 34433 Istanbul, for Istanbul UniversityYenikapı Shipwrecks Project, 2008, €70 (hbk), ISBN978–9758072163

In this first volume of a planned series dedicated topresenting the Byzantine-era shipwrecks of Yenikapı,editor Ufuk Kocabas co-ordinates an introduction tothree years of archaeological excavation at a complexsite in the heart of ancient Constantinople and modernIstanbul. As noted in presentations at the recent 12thInternational Symposium for Boat and Ship Archaeol-ogy (ISBSA) nearby, 34 shipwrecks survived in deepsilt that gradually choked the ancient harbour built bythe emperor Theodosius (c.379–395 AD). The oldestsite in Istanbul (6th millennium BC), early city walls(4th century AD), limestone quays, and wooden piersalso emerged from the dark, rich soil at the site, now akilometre from the sea.

Istanbul Archaeological Museums has responsibil-ity for excavations within the city, and when a massiveinfrastructure-building project to bring rail and metrotransportation began, the archaeological componentplayed a critical role. Four stations will be linked byrail laid under the ancient city and more than 50 mbelow the Bosporus in a plan to connect the city’sEuropean and Asian sectors. The Turkish Ministry ofTransportation and the Metropolitan Municipality of

REVIEWS

© 2010 The Authors. Journal Compilation © 2010 The Nautical Archaeology Society 205