Maurice Ravel Frontispice - Bolero

-

Upload

fred-fredericks -

Category

Documents

-

view

36 -

download

7

description

Transcript of Maurice Ravel Frontispice - Bolero

-

Bolro

Just before departing on his American Tour in 1928, Ravel received a commission fromIda Rubinstein for a ballet, to be called Fandango. His intention was to orchestrate somepieces from Iberia by Albniz, but as he was beginning work on it in July, he discoveredthat the rights to the music were already assigned to the Spanish composer EnriqueArbs. Ravel was initially dismayed and at a loss how to fulfil his commission. Howeverwhile continuing his holiday in Saint-Jean-de-Luz, he developed a Spanish-soundingtheme which had about it "quelque chose d'insistant".

"L'homme de la rue sedonne la satisfaction de

siffler les premiresmesures du Bolro, maisbien peu de musiciens

professionnels sontcapables de reproduirede mmoire, sans une

faute de solfge, laphrase entire qui obit

de sournoises etsavantes coquetteries."

( mile Vuillermoz,[1938], p.88-89).

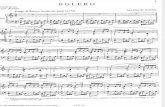

Bolro, as the work was renamed, lasts approximately15 minutes, and repeats each of the theme's two parts9 times in the same key, using different orchestrationsto vary the texture and to create a gradual crescendo.(The pattern is AA BB repeated 4 times, and then asingle repeat of AB, leading to the modulation whichgives the piece its cataclysmic ending.)

Ravel was insistent that the work should be played ata steady and unvarying tempo (as his own recordingdemonstrates). "C'est une danse d'un mouvement trsmodr et constamment uniforme, tant par la mlodieque par l'harmonie et le rythme, ce dernier marqusans cesse par le tambour. Le seul lment dediversit y est apport par le crescendo orchestral."(Ravel, [1938]). After a performance in 1930, hereprimanded Toscanini for taking the work too fast andfor speeding up at the climax. (Coppola, [1944],p.105)

At the first performance of her ballet production,at the Opra in November 1928, Ida Rubinsteindanced the role of a flamenco dancer who istrying out steps on a table in a bar, surroundedby men whose admiration turns to lustfulobsession. Ravel did not entirely approve; hisown conception was an outdoor scene in front ofa factory whose machinery provides the

In concert performances,Bolro became Ravel's most

popular work, and it is reputedto be the world's most

frequently played piece ofclassical music. The royalties

earned by the work up to 2001

http://www.maurice-ravel.net/index.htmhttp://www.maurice-ravel.net/ida.htmhttp://www.maurice-ravel.net/bibliog.htm#vuillermoz%22http://www.maurice-ravel.net/bibliog.htm#ravelhttp://www.maurice-ravel.net/bibliog.htm#coppola

-

www.maurice-ravel.net

inflexible rhythm; the factory workers wouldemerge to dance together, while a story of abullfighter killed by a jealous rival was playedout. ( Chalupt, [1956], p.237). It was performedin this way, with designs by Lon Leyritz, at theOpra on one occasion after Ravel's death.

have been estimated at 40million: an article outlining thestrange history of this moneyappeared in The Guardian on

25 April 2001.

Much has been written about Bolro. One detailed analysis of its structure appears inDeborah Mawer's chapter, "Ballet and the apotheosis of the dance", in The CambridgeCompanion to Ravel, [2000], pp. 155-161. The impact of its repetitive technique (e.g.4037 drum beats) is considered by Serge Gut in "Le phnomne rptitif chez MauriceRavel: de l'obsession l'annihilation incantatoire", in International Review of theAesthetics and Sociology of Music, vol.21(1) [June 1990], pp.29-46. [For those withaccess to JSTOR, an online version of this article is available.]

Claude Lvi-Strauss considers the semiotics of the work in "Bolro de Maurice Ravel", inL'Homme, vol.11(2), [1971], pp. 5-14.

And from a performer's perspective, Jean Douay has written about the role of thetrombone - and how to play it - in "Thoughts to Ponder: What Would Ravel Think?--MoreThoughts on Ravel's 'Bolero'", in ITA Journal, vol.26(2), [Spring 1998], p. 23.

http://www.maurice-ravel.net/index.htmhttp://www.maurice-ravel.net/bibliog.htm#chalupthttp://www.maurice-ravel.net/leyritz.htmhttp://www.guardian.co.uk/g2/story/0,3604,477906,00.htmlhttp://www.maurice-ravel.net/bibliog.htm#mawerhttp://uk.jstor.org/view/03515796/ap030038/03a00020/0?config=jstor&frame=noframe&[email protected]/028258cb3a297fdde1b87ab&dpi=3