Mathews, Knowledge, Power:Ignorance

-

Upload

cara-kerven -

Category

Documents

-

view

233 -

download

0

Transcript of Mathews, Knowledge, Power:Ignorance

-

8/3/2019 Mathews, Knowledge, Power:Ignorance

1/27

Power/Knowledge, Power/Ignorance: Forest Fires and the State in MexicoAuthor(s): Andrew S. MathewsSource: Human Ecology, Vol. 33, No. 6 (Dec., 2005), pp. 795-820Published by: SpringerStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4603602

Accessed: 11/11/2010 07:19

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available athttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless

you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you

may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at

http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=springer.

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed

page of such transmission.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

Springeris collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access toHuman Ecology.

http://www.jstor.org

http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=springerhttp://www.jstor.org/stable/4603602?origin=JSTOR-pdfhttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=springerhttp://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=springerhttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/stable/4603602?origin=JSTOR-pdfhttp://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=springer -

8/3/2019 Mathews, Knowledge, Power:Ignorance

2/27

Human Ecology, Vol. 33, No. 6, December 2005 (? 2005)DOI: 10.1007/s10745-005-8211-x

Power/Knowledge, Power/Ignorance: Forest Firesand the State in MexicoAndrew S. Mathews'

For over a century the Mexican state has justified its control of forests byclaiming that ruralpeople are ignorant and destructive ire setters, in thefaceof abundant evidence to the contrary.Academic and popular stereotypes ofthe state have tended to assume that official power and knowledge go handin hand. In an institutionalethnography of the Mexican environmentagency,SEMARNAP, I show how official ignorance is deployed both within andoutside stateforestry institutions,and how ignorance and complicity may beas importantas knowledge in assertingstatepower. Ratherthan internalizingofficial fire discourse, ruralpeople in Mexico learn to mouth polite fictionsin their encounters with officials. I argue that the scholarship on governmen-tality derived from Foucault has uncritically internalized the link betweenpower and knowledge. A closer attention to the production and translationof knowledge within state institutions leads to a more nuanced understand-ing of various forms of obscurity and ignorance which accompany officialknowledge claims.KEY WORDS: forestry;fire management; local knowledge; Mexico.

'If the law supposes that,' said Mr. Bumble, squeezing his hat emphatically in bothhands, 'the law is a ass-a idiot. If that's the eye of the law, the law is a bachelor;andthe worest I wish the law is, that his eye may be opened by experience-by experience.'Oliver Twist (Dickens, 2001:558)INTRODUCTION2

Throughout the twentieth century the Mexican state has asserted itsright to control forests using a variety of justifications, from climate control,1Department of Sociology & Anthropology, Florida International University, Miami, FL.2Thispaper is drawn from my fieldwork and archival research in Mexico in the summer of 1998and between April 2000 and August 2001.

7950300-7839/05/1200-0795/0 ? 2005 Springer Science+Business Media, Inc.

-

8/3/2019 Mathews, Knowledge, Power:Ignorance

3/27

796 Mathewsto industrial logging, from flood control, to forest fire suppression. As otherpolicies have come and gone, fire control has remained central to officialrhetoric. Government officials have vilified traditional agropastoral usesof fire, and have sought to convert rural Mexicans into willing firefight-ers. According to these officials, fire is uniformly destructive, and agricul-tural uses of fire must be severely regulated and controlled. In 2003, thehead of the national forest commission, Alberto Cardenas, made a typi-cal restatement of official fire discourse, declaring that many forest fireswere caused by the careless, indiscriminate, and inappropriate use of 'slash-and-burn agriculture' (tumba roza y quema),3 which he claimed was notonly "non-functional, but unnecessary"4 (Gomez Mena, 2003). Accordingto Cardenas, fire and the irrational peasant farmers who burned their landwere among the chief causes of deforestation and forest destruction. Thisofficial fire discourse flies in the face of voluminous evidence that manyfires are not destructive, and that they are set for deliberate purposes andcontrolled.

States have often deployed negative stereotypes of particular groupsin order to justify their power (e.g., Dove, 1983; Said, 1979). In Mexico,the state has justified its efforts to control forests and modernize agricul-ture by stereotyping agricultural and pastoral fire users as irrational andignorant. Mexico is by no means unique in this; as Pyne (1993) points out,with its ability to transform landscapes and jump boundaries, fire is partic-ularly problematic for modern states which seek to stabilize nature and so-ciety. In the United States, the historic experience of forest fire suppressionhas been increasingly recognized as ecologically problematic (Crutzen andGoldammer, 1993; Pyne, 1998), and the United States' experience of firesuppression has been a powerful influence on the Mexican forest service.5In this article I examine the ways in which stereotypes of fire useare produced and maintained in order to question our understandings ofthe modern state and of the role of knowledge in asserting state power. I ar-gue that the case of firefightingand fire management in Mexico can yield thecounterintuitive lesson that state power may depend upon a managementof ignorance and of knowledge by officials and their clients. Further, thatvarious forms of ignorance may be a feature of modern state institutions ingeneral rather than only of relatively weak and poorly funded conservation3Tumba roza y quema (cut, slash and burn) is the derogatory term used by the Mexican state todescribe a wide variety of long fallow agricultural systems which make use of forest biomassfor fertilizer. For the remainder of this article I will use the term 'swidden.'4All translations from Spanish are my own.5Since the first modern forest law of 1926, Mexican forestry institutions have been marked byinstability and frequent transfersbetween ministries. I use the term 'forest service' to indicatethe federal institutions responsible for forest management and protection. Between 1994 and2001, this was the Secretariat of Environment and Natural Resources, SEMARNAP.

-

8/3/2019 Mathews, Knowledge, Power:Ignorance

4/27

Power/Knowledge, Power/Ignorance: Forest Fires and the State in Mexico 797

institutions such as the Mexican forest service. The Mexican forest servicedoes not ignore fires because it is irrational or insufficiently modern butbecause strategies of ignorance and of knowledge production are central tothe assertion of bureaucratic power and rationality. The illusion of the mod-ern state which collects, orders, and manages information has clouded ourunderstanding of the state as a set of institutions where officials and theirclients manage categories of transparency and obscurity.I show here how Mexican officials and their clients stabilize official firediscourse by colluding in various forms of knowledge and ignorance pro-duction. First, official forestry discourse blames the past failures of the for-est service upon corruption, obscuring the systemic political and economicfactors that have undermined the success of forest policies. Second, officialsare materially ignorant of the number, location, and causes of agriculturalfires as a direct result of unenforceable fire control regulations that leadrural people to conceal their burning practices from official notice. Third,government officials are influenced by official fire discourse to misrecog-nize agricultural fires as being irrational, uncontrolled, and uniformly de-structive. Finally, intrusive fire control regulations provide symbolic capitalwhich allows officials to exercise their arbitrary power to turn a blind eyeand 'officially ignore' local fire use practices.

STATE MAKING AND OFFICIAL KNOWLEDGEIn recent years, poststructural theorists have forcefully critiqued theidea of the unitary state; in a seminal and oft-cited article Philip Abramsargued that the idea of a powerful and unitary state was an illusion whichconcealed the real lack of state integration, and that the idea of unity was

manipulated by powerful interest groups in order to achieve domination(Abrams, 1988). Foucault famously refrained from a theory of the statebecause it was an 'indigestible meal' (Gordon, 1991, p. 4), preferring toconcentrate on the "techniques of power/knowledge, designed to monitor,shape, and control the behavior of individuals situated within a range of so-cial and economic institutions such as the school, the factory and the prison"(Gordon, 1991, p. 3). Following these thinkers, a slew of scholars have an-alyzed various aspects of state fetishism (Coronil, 1997), and imaginings ofthe state (Tsing, 1993).This disaggregation of the state has, however, not been paralleled bya systematic rethinking of the relationship between power and knowledgeoutlined by Max Weber, who described how modern states expanded theirpower through increased control of the means of rational public administra-tion (Gerth and Mills, 1958; Weber, 1978). Although he rejected Weber's

-

8/3/2019 Mathews, Knowledge, Power:Ignorance

5/27

798 Mathewsemphasis upon state institutions and state rationality, Foucault implicitlyaccepted that state power was built upon state knowledge and disregardedboth internal conflicts within bureaucracies, and the ways in which stateknowledge might be a rhetorical claim in which officials themselves hadlittle belief (Foucault, 1991b, p. 133). My argument here is in direct dis-agreement with Foucault and Weber. The various forms of official igno-rance, misrecognition, collusion and complicity, and acts of official ignoringcarried out by Mexican forestry officials and their clients imply a muchmore complex relationship between power and knowledge than is sug-gested by Foucauldian studies of power/knowledge. In addition, the hier-archical structure and culture of the Mexican forest service, with high levelofficials based in Mexico City asserting control over the creation and in-terpretation of regulations, cannot be successfully understood by entirelyignoring the structures of the state. Although the state is not monolithic,neither is it completely diffuse; as Sivaramakrishnanpoints out, the state isa more or less loosely linked set of institutions of varying unity and strength(Sivaramakrishnan, 1994), which are notably patchy spatially (Craib, 2002;Winichakul, 1994) and discontinuous in time (Anderson, 1991). These insti-tutions generate forms of knowledge and ignorance that are not uniformlyspread out as 'official knowledge' accepted by all officials. In some casesstate power is premised directly upon an official ignorance which mustbe carefully maintained in order to allow state officials to make claims toknowledge, and to affirm their status as representatives of a state whichknows, manages, and makes use of information. These knowledge claimsare symbolic capital which with which officials assert their authority in rou-tine, unofficial encounters with their clients, and in encounters betweenhigher and lower level officials.Foucault himself largely accepted the power of diverse institutions tocontrol the subjects of rule, most importantly by seeking to effect a 'conductof conduct,' (Foucault, 1991a), whereby a particular combination of powerand knowledges ('savoirs') was deployed upon people who came to be dis-posed to act according to official definitions of right and wrong. A broadswath of scholarship on governmentality has followed Foucault in accept-ing that various institutions succeed in altering subjectivities through partic-ular forms of rationality and calculation (Rose, 1999b); scholars have dulytraced the workings of governmentality in a wide range of locations fromtransnational government institutions (Ferguson and Gupta, 2002) to immi-gration institutions (Morris, 1998). Paradoxically, this scholarship has paidgreat attention to official projects, and has largely failed to carry out thekind of micropolitical studies which Foucault himself might have advocated.This has led scholars of governmentality to largely miss the private encoun-ters and public complicities where projects of governmentality are modified

-

8/3/2019 Mathews, Knowledge, Power:Ignorance

6/27

Power/Knowledge, Power/Ignorance: Forest Fires and the State in Mexico 799

or evaded entirely, whether within the bureaucracies which claim to en-force them, or in meetings between bureaucrats and their clients.6 Watts(2001, p. 286), points out the first generation of poststructuralist studies ofdevelopment institutions lacked empirical detail and assumed that these in-stitutions were much more powerful than they really were (Escobar, 1991;Ferguson, 1994). In the realm of environmental anthropology, Fairhead andLeach (2000b) described how an official discourse of environmental degra-dation was used to justify the power of colonial and postcolonial states,but they gave relatively little attention to the interactions between forestryofficials and their clients where official environmental discourse remainedlargely unchallenged and the regulations it inspired largely unenforced. Be-yond the realm of governmentality studies, James Scott's Seeing Like a State(1998) paid great attention to authoritarianprojects of legibility and controland lauded the practical knowledge of small farmers, but paid little atten-tion to the ways in which these two forms of knowledge might be kept sepa-rate by acts of practical ignoring. Similarly, Scott did not discuss what mightbe called the 'private environmental transcripts' where peasants mouthedofficial discourse in order to avert trouble. All of these studies share a simi-lar preoccupation with the production of authoritative knowledge, but havepaid little attention to the various forms of official ignorance and the normsof discourse which demanded that official statements remain unchallengedin public.A recent generation of ethnographies of conservation and devel-opment which focus on policy implementation rather than upon officialrhetoric alone have shown how governmentality is rarely achieved or evenbelieved in by the officials who propound it (Li, 1999). As Tania Li suggests,scholars of governmentality have too easily accepted that governmental-ity is achieved. Rather it is what state officials would like to do, what theyclaim to do when they seek to justify their actions to higher authority, butseldom what they can do in practice. Li describes the collusion by whichdevelopment officials and their clients avoid confronting the failures of de-velopment policies; this points to the existence of powerful norms wherebypublicly unquestioned official discourse is used to support the authority ofofficials. In other words, official knowledge may not publicly contradicted,but this does not mean that it is accepted or internalized by its clients or bythe officials who pronounce it. As Moore (2001) points out in the case of de-centralization initiatives in West Africa, officials and their clients alike con-sider international development discourse to be a 'public secret' in which6Foucault had relatively little to say on governmentality and was rather inconsistent upon thesubject (see (Rose, 1999a: p. 23). The subsequent explosion of 'governmentality studies' mayitself be an indication of the way in which the idea of the knowing state has been internalizedby scholars of the state.

-

8/3/2019 Mathews, Knowledge, Power:Ignorance

7/27

800 Mathewsno one believes, but which they will not publicly challenge. Fairhead andLeach, (2000a), in a reassessment of their earlier work point out that offi-cial environmental discourse is rarely challenged in public, but that this doesnot prevent local people from subverting or ignoring forestry regulations.For our present purposes, the chief weakness of the older governmentalityliterature has been that it is too hasty in accepting the power of official dis-course to mould people's behavior, and that in discarding the unitary stateit has focused too much on decentered power and 'authorless strategies,'and paid insufficient attention to the actual structures and policies of stateinstitutions. These institutions are not monolithic, but they do have somecontinuity in time and in space, and have internal hierarchies and politics ofknowledge and ignorance.

VERNACULAR UNDERSTANDINGS OF FIREIn 2000-2001 I carried out ethnographic research on the Mexican

forest service in Oaxaca and Mexico City, and in the forest community ofIxtlan in the Sierra Juarez of Oaxaca in Southern Mexico.7 Initially, I foundalmost universal agreement among foresters, government officials, andcommunity members that fire was solely destructive, and that right-mindedpeople should come together to fight fires. However, I began to realize thatbehind this apparent unanimity lay an evasion of government ideology, anda set of fugitive practices where rural people made use of fire in agriculturewhile mouthing prophylactic official fire control language. In a meetingbetween forest service officials and forest community leaders in the cityof Oaxaca in 2001, speaker after speaker extolled the communities' com-mitment to firefighting, and denounced the destructive effects of wildfire,comparing other peoples' 'carelessness' with their own virtue. In private,many of these same community members were much more ambivalentabout fire, telling me that fire could assist forest regeneration and be usedin agriculture. In communities where the forestry and logging factions hadgained control of community institutions, fire control had been adoptedas a political and environmental project, but in many communities, firecontinues to be an integral part of agriculture and pastoralism.

7Research in Mexico City consisted of archival research and 17 interviews with present orformer senior forestry and environment officials; research in the city of Oaxaca consisted ofarchival research and 45 interviews with foresters and forestry officials;research in the SierraJuarez consisted of 40 interviews with community members, together with archival researchand participantobservation of forestry operations and meetings between forestry officials andcommunity members.

-

8/3/2019 Mathews, Knowledge, Power:Ignorance

8/27

Power/Knowledge, Power/Ignorance: Forest Fires and the State in Mexico 801In the forest community of Ixtlan, traditional knowledge of agricul-tural uses fire formed the basis for a critique of the dominant fire controldiscourse, as one elder told me:

These people [i.e. the foresters] who run things now, they look for people to planttrees, but they don't know that with burning the seeds fall and the plants grow upby themselves. And they pay people to plant trees.As I got know people in the community better, a very different accountof fire began to emerge. According to community elders, fire had formerlybeen a valued tool in agriculturalpractices; fire was destructive in the con-text of forest management, but they did not think of agricultural fires asirrational, destructive, or immoral, concentrating their disapproval on firesset incompetently or carelessly. They described techniques for controllingand using fire, and while they admitted that fires could escape cultivation,they described fire as a pragmatic tool rather than as the voracious and uni-formly destructive force imagined by government officials.8Elders in Ixtlan agreed that fire had formerly been an integral part ofthe agricultural cycle,9 and that it could usually be controlled by cutting asmall firebreak with a hoe, and then burning carefully from the downhilledge of the field. Farmers had strong pragmatic reasons for controlling fire;if it went into a neighbor's land it could cause recriminations or conflicts,or even fines if the community decided that it had been set carelessly orinappropriately. In addition they had to judge when to burn safely, ac-cording to time of day, wind speed, and the dryness of the vegetation. Ifthe fire burned too cold it would not remove the vegetation, making cul-tivation difficult and reducing the fertilizing effect of the ash; if it burnedtoo hot it could escape or damage the soil. While they did not deny thatagricultural fires occasionally escaped from cultivated fields into surround-ing forests, people were at pains to make clear how and why fire could becontrolled.Peasant farmers in Ixtlan and other parts of Mexico often pay onlylip service to official fire regulations. Fire continues to be integral to agri-culture all over Mexico.10 Far from being reckless users of fire, Mexican

8For a full discussion of the shifting meanings of fire in Ixtlan see (Mathews, 2003). The benignuses of fire have been marginalized within the community of Ixtldn due to the creation ofcommunity forestry institutions.9The use of fire in agriculture in the Sierra Juarez has declined with the rise of industrialforestry so discussions of fire use refer to former practices (see Mathews, 2003). For a goodrecent ethnography of agriculturein the Sierra Juarez see Gonzalez, 2001.?0Evenaccording to the suspect official figures there were over 8000 recorded forest fires in2000, averaging 2.8 ha. in size (Galindo et al., 2003). Total area of agricultural fires has beenestimated at 3-4 million hectares per year (Catterson et al., 2004, p. 28).

-

8/3/2019 Mathews, Knowledge, Power:Ignorance

9/27

802 Mathews

farmersil use fire carefully as a part of the milpa system of swidden cultiva-tion in which forest or scrub is cut, the residue is stacked, dried, and thenburned; after this the field is cultivated for several years, when it is aban-doned to return to scrub or forest. There are a myriad variations on thisform of agriculture across Mexico, from complex polycultures with long pe-riods of fallow in tropical moist ecosystems (Alcorn, 1984; Mathews, 2003;Xolocotzi, 1959 (1987)), to relatively short fallow periods and less complexcrop mixtures in temperate ecosystems (Nigh, 1975; Tyrtania, 1992). In allof these agroecological systems, farmers take great care to control fire, ashas been repeatedly pointed out by Mexican agronomists as far back as 1916(Calvino 1916 (op.cit.Toro, 1981 (1945))). Farmers have to judge carefullywhen a successful burn is most likely to achieve an even coating of fertiliz-ing ashes and to prevent the fire from escaping: as Efrain Xolocotzi pointsout for the milpa farmers of Yucatain,"When to burn, whether to burn orto delay the burn, is the annual problem which is most difficult to resolve"(Xolocotzi, 1959 (1987), p. 397).

Farmers across Mexico continue to discreetly make use of fire whileavoiding official fire control regulations, which they deeply resent (Haenn,2005, pp. 199-203). These controlled agricultural uses of fire are rarelybrought to the attention of the authorities, who continue to see agricul-tural users of fire as irrational, drunken, or ignorant. The separation of of-ficial and vernacular spheres is so complete that it is only on relatively rareoccasions that peasants confront state officials and complain about officialfire control regulations. One such case occurred in the state of Campechein 2002, when peasant farmers protested at the Ministry of Agriculture(SAGARPA), claiming that many of them had suffered from legal sanc-tions against swidden agriculture,which was practiced by "90%"of the agri-culturalists of Campeche (Perez U., 2002).

OFFICIAL DISCOURSE AND PRIVATE KNOWLEDGE:MAINTAINING SYMBOLIC CAPITAL IN ANUNCERTAIN WORLD

Mexican forest service officials were often privately ambivalent aboutthe regulations they were publicly committed to enforcing. They told meof the tension between their public role as representatives of the state,and their private role as the often skeptical subjects of state power who

11Pastoralists also make use of fire to encourage the re-growth of fresh grasses; this use of fireis not well studied in Mexico, but it is probable that pastoralists are as careful as farmers, andthat pastoralists' use of fire has been similarly obfuscated and ignored by the Mexican state.

-

8/3/2019 Mathews, Knowledge, Power:Ignorance

10/27

Power/Knowledge, Power/Ignorance: Forest Fires and the State in Mexico 803

recognized that these regulations could be impossible to apply. As one se-nior official told me:

The thing is that we are used to acting on the margin of the law in our daily life, yousee [the law] as a hazard of life, as a pain in the ass ... but in the moment of writingwe try to create a perfect law. And either we don't think about how the law will beapplied, or we think that it will be applied and obeyed.This statement pointed to the separation between the world of the officialswho designed these regulations and that of those who had to enforce them.In practice the forestry officials who are supposed to apply regulations areforced to modify or ignore many of them; this autonomy is seldom officiallyrecognized or recorded, so that official power comes to be premised uponthe ignorance of the high level officials who design the regulations.Historically, the Mexican forest service has been a weak institu-tion with inadequate budgets and subject to frequent radical reorganiza-tions (Klooster, 2003; Mathews, 2004). This institutional fragility contrastsmarkedly with the striking stability of the forest service's ideologies ofnatural resource control. Over the past century the forest service has re-mained committed to preventing forest fires, to controlling or preventinggrazing in forests, to strictly demarcating agriculture from forestry, to ap-plying forestry to the 'disordered' forests and to regulating access to foreststhrough an elaborate system of documents and regulations.

From the first modern forest law of 1926 (Gutierrez, 1930a, 1930b;Mares, 1932;Pesca, 1930,1932) to the most recent fire regulation (SEMAR-NAP, 1997b), deliberately set fires have been in theory severely regulatedand controlled. In practice, the forest service has never had the manpowerto enforce these regulations; fire is integral both to agricultureand pastoral-ism in large parts of Mexico, and a strict policy of fire control would havebrought cultivation to a halt in many areas. Indeed, had any of these fireregulations been uniformly enforced they would have imposed a crushingburden of paperwork upon the forest service.According to the 1930 fire control regulation, landowners were sup-posed to apply for written permission from the forest service in advance,with details of the proposed burn. The 1997 fire regulation similarlyrequirefarmers to apply for permission, stating such information as reason for burn,time, date, etc. Although the 1997 regulation is much more detailed thebroad outlines remain the same. The fact that an unworkable regulation hasbeen restated after over 70 years of apparent failure (during which multiplesimilarly unenforceable regulations were issued) suggests that the meaningof these regulations lies outside of their applicability. These regulations de-fined an enormous field of behavior as criminal, and asserted officials' rightto punish such behavior in selected cases if they chose to do so. Rather than

-

8/3/2019 Mathews, Knowledge, Power:Ignorance

11/27

804 Mathewsbeing a 'failure' the regulations created symbolic capital and discretionarypower for officials, compelling people who chose to burn to do so eitherdiscretely or in total secrecy. The effect of official strategies of regulationand legibility was to inspire many people to create zones of illegibility andignorance; official knowledge resulted in official ignorance as to the loca-tion and extent of burning.'2 Notice that this form of ignorance is defined interms of official definitions of knowledge-to this day forestry officials arethe first to admit that they have little knowledge of the location and size offires.

Official ideology about the degrading effects of fire is continually gen-erated and restated in forest service offices in Mexico City, and then en-coded in successive fire control regulations. This fire discourse is rigorouslyprotected from challenge by field level foresters or rural people; workingforesters are allowed to negotiate the tension between official ideology andlocal practice by allowing exceptions or turning a blind eye, but these lo-cal exceptions are rarely documented and do not challenge the status ofnational regulations and official pronouncements. Following Bowker andStar's analysis of the zones of obscurity created by particular forms of clas-sification (Bowker and Star, 1999, pp. 278-282), we can see that the sys-tem of fire classification designed by the Mexican state has made manyfires obscure-the many small and controlled 'illegal' fires become offi-cially invisible. In seeking to control the micro-details of fire managementthrough detailed regulations, the designers of the regulations actually madeit impossible to follow even the broad outlines of rural fire managementpractices.This raises the question of whether high-level officials cynically deployfire control discourse in order to maintain state power, or whether it is main-tained constant through a more subtle process of inculcation, where highlevel officials are simply unaware of what is going on in the field. I sug-gest that both these processes take place: high level officials may be awarethat official policies are futile or incorrect, but they also come to partiallyor completely accept the premises of these policies, through the kinds ofinculcation described by Bourdieu (1994) and Douglas (1986)."12Regulations aimed at controlling firewood cutting and illegal logging resulted in similar offi-cial ignorance of firewood use and logging.I31t is of course impossible to find out people's private beliefs and personal uncertainties inthe course of the kind of one or two hour interview I carried out during my research. Never-theless, forestry officials were usually remarkably frank and critical of their own institution,whilst the change of administrations in 2000-2001 gave me a chance to interview a number offormer officials who were more than willing to criticize new forest policies. The fact that thesepresent and former officials who were otherwise critical of the forest service largely neglectedto criticize the unreality of official regulations over fires and firewood all strongly suggest thatthese officials were either unaware or uninterested in problems of implementation.

-

8/3/2019 Mathews, Knowledge, Power:Ignorance

12/27

Power/Knowledge, Power/Ignorance: Forest Fires and the State in Mexico 805

THE CULTURE OF STATE FORESTRY INSTITUTIONS14In 1994 responsibility for forest management and protection wasmoved from the secretariats of agriculture (SAG), hydraulic resources(SARH) and social development (SEDESOL) to the new Secretariat of

Environment, Natural Resources and Fisheries (SEMARNAP), under thebiologist Julia Carabias Lilo. In 2000-2001 SEMARNAP was a formidablylarge organization, with a total of 37,000 employees in the whole of Mexico,for all aspects of environmental management. The majority of these em-ployees were lower level administrative 'base' employees (de base), orworked in other fields, so only around 200-300 of this number wereforesters.15 The total number of employees was far outweighed by theirenormous responsibilities: in the state of Oaxaca in 2000, around 40 pro-fessional and 200 administrative 'base' employees were responsible forall aspects of environmental management, including 5.1 million hectaresof forest.16 At a national level, responsibility for forestry was spreadover nine general directorates, including Wildlife, Environmental Impact,Forestry, and Renewable Resources (SEMARNAP, 2001; SEMARNAT,2001), other directorates were responsible for such areas as fisheries andindustrial pollution. Most of the functions to do with forestry were concen-trated in a complex of two story buildings in the Viveros de Coyoacan inMexico City.The political power of the presidency of Ernesto Zedillo (1994-2000)directly affected the stability of natural resource management institu-tions; the six year presidential term, or 'sexenio,' was also the lifetime ofSEMARNAP as an institution.17In the first years of each sexenio, the newpresidential administration attempts to represent itself as completely dif-ferent from the old (supposedly corrupt) regime (Morris, 1991). The as-sertion that the previous administration was corrupt creates a conceptualboundary which defines the new institution in time, obscures the conti-nuity of the past with the present, and ensures that past forest policiesare not systematically analyzed. In addition, by blaming past failures on

14For a history of forestry and conservation in Mexico see (Klooster, 2003; Simonian, 1995).15Other specialists were biologists, agricultural engineers, lawyers, etc. who were far outnum-bered by a large cadre of less specialized administrative 'base' staff.Because Oaxaca has little industry, the majority of these employees dealt with forest man-agement or conservation.17In 2001 responsibility for fisheries was transferred to the Secretariat of Agriculture, resultingin the change of SEMARNAP's name to SEMARNAT (Secretariat of Environment andNatural Resources), while forestry subsidy programs were moved to a new national forestrycommission CONAFOR.

-

8/3/2019 Mathews, Knowledge, Power:Ignorance

13/27

806 Mathewspersonal corruption rather than on systemic political or economic factors,the corruption accusation actually bolsters the legitimacy of the incumbentadministration. Individuals may be well aware that past administrationswere not in fact uniformly corrupt, and they are often familiar with the de-tails of past policies and legislation, but this knowledge is marginalized byofficial discourse of past corruption which renders their personal knowledgeirrelevant or politically inconvenient.The overwhelming power of the presidency, and the need for offi-cials to scramble for office at the end of each sexenio means that theyhave to be acutely aware of political currents at higher levels and to main-tain patron-client relations with higher level officials in order to secureemployment (Grindle, 1977; Lomnitz, 1982; Lomnitz et al., 1983). Theserelationships are not necessarily permanent but they do provide an essen-tial resource for aspiring functionaries as they attempt to build careers.As well as building upward links, officials need to build relationships withlower level officials, both in order to provide themselves with a cadre ofpossible assistants and to increase their chances of being offered a jobby a colleague or former employee if they lose their position. In an at-mosphere of uncertainty about the future, senior figures seek to protectthemselves by choosing competent assistants with whom they are person-ally acquainted, and who they can trust not to embarrass or compromisethem. These are the empleados de confianza, the well-named "employeesof trust," the team upon whom an official will rely during his tenure ofoffice.Each successive administration distinguishes itself from its predecessorby dismissing most of the empleados de confianza. Nevertheless, valuableand highly trained officials can often secure a position with the incoming ad-ministration, sometimes after an interval of a few months which preservesthe official fiction of a new administration. On the other hand, young andrelatively inexperienced individuals may be appointed to high positions be-cause they can plausibly be represented as untainted by associations withthe previous regime.18 High office carries its risks: the higher the position,the more certain it will be lost in a change of administrations. For those whodo not have the political connections to aspire to high office, the objectiveis to avoid rising too high or sinking too low.

18With the declining legitimacy of the PRI state from the early 1980s onwards, the Mexicangovernment increasingly recruited prominent critics of its policies into senior administrativepositions in order to gain some credibility. Julia Carabias was one example of this patternof recruitment; a number of officials in her administration had had careers as NGO activistsopposed to the state.

-

8/3/2019 Mathews, Knowledge, Power:Ignorance

14/27

Power/Knowledge, Power/Ignorance: Forest Fires and the State in Mexico 807FORMAL CONTROL AND INFORMAL AUTONOMY:

INFORMATION FLOWS BETWEEN CENTER AND PERIPHERYHigh level officials based in Mexico City have a great degree of formalpower, but are continually troubled by a sense of weakness-as one officialtold me:They tell you "yes we are going to do it," but then they don't ... their job is to pre-tend that the machine works as you tell it to. They say that the person who controlsan office is the head of the organization, when in reality he doesn't even know if [hissubordinates] do their jobs or not, when they don't want to accept what the chiefsays.

This comment illustrates senior officials' fear that although they havecontrol of the forms of power, they must constantly struggle to maintain itsreality because their subordinates will keep information from them. In 2001,Julia Carabias told me that her best means of finding out what was goingon was by relentlessly touring the states and reading the petitions and pleaspresented to her on these trips. Although these tours were carefully or-chestrated by state delegations of SEMARNAP, who attempted to presentthe appearance of things working smoothly, there is a strong tradition ofpeople bypassing local officials by taking petitions directly to the head ofthe bureaucracy. Thus, such tours emphasize the personal power of theSecretary.Another reason that high level officials fear that they may be out oftouch is that there are strong norms against sending bad news to higher lev-els, at least in written form. It is so risky for subordinates to express strongopinions that policy suggestions from below are often made in the form ofanonymous memos (notas informativas), which are edited and altered asthey travel through the system, further emphasizing how written informa-tion is compelled to conform to official norms and policies. Written infor-mation asserts the power of high level officials because it must conform toofficial categories and represent official realities; thus, the continued send-ing of reports from the provinces is more important than the actual contentof the reports (which senior officials profess not to believe in any case)."9Although SEMARNAP made a significant effort to decentralizedecision-making in 1994-2001, control over finances remained highly cen-tralized and budgetary and staffing decisions continued to be made inMexico City. This meant that the central offices retained a large degreeof control over level SEMARNAP offices. Information about spending19As Dove and Kammen point out, "when continual communication is necessary for govern-ment, its purpose is meta-communication and control, not the conveyance of any particularmessage or promotion of dialogue" (2001).

-

8/3/2019 Mathews, Knowledge, Power:Ignorance

15/27

808 Mathewshad to flow to central offices, and state level officials faced the onerousaudit procedures faced by all upper level functionaries.20 Senior officialsalso had a great degree of control over the formal definition of officialprograms and policies. However, state SEMARNAP officials had a con-siderable degree of autonomy in deciding how or whether to implementprograms or enforce regulations, partly because regulations were so am-bitious and voluminous that they necessarily had to choose among them,and partly because programs aimed at encouraging reforestation or forestmanagement could only reach a fraction of the possible recipients, so thatthey had a great deal of freedom in determining how to allocate resourceslocally.

The strong norms against putting bad news in writing ensure that for-mal regulations define the kinds of written information that the state leveloffices will send to the center. A good example of this was the most re-cent regulations for controlling the agropastoral uses of fire (SEMAR-NAP, 1997b) and the collection of firewood (SEMARNAP, 1996). Statelevel SEMARNAP officials-in-oaxaca told me that they had decided notto pay much attention to the new fire control regulation because theylacked the resources to implement it and trying to do so would havedamaged their relationship with the community fire brigades who carryout the bulk of fire control. Rather than tell the center that it was un-enforceable, the state level officials in Oaxaca sent a copy of the newfire regulation to all the municipal authorities in the state. This de factolocal autonomy was accompanied by tactful silence on the part of localofficials and community leaders; the officials were careful to avoid writ-ten or public criticism of the fire control regulations; community leaderswere similarly careful to avoid bringing the topic up in regional forest fo-rums where forest policies were discussed, preferring to concentrate onthe more pressing matter of industrial logging and government subsidies.On the other hand, private conversations are an acceptable context forcriticizing official policies. This makes personal contacts all the more im-portant, both for officials who wish to find out what is "really" going on,and for people who are soliciting official action. State level officials travelto Mexico City to talk to their superiors because personal contact is all-important for finding out which policies really need attention and for re-assuring higher level officials that their subordinates are indeed carryingout their work, as well as maintaining relationships critical for future careeradvancement.20Over the last twenty years, there has been a proliferation of complex administrative controlsover public expenditures: these audits are time consuming and exhaustive but it is not clearthat they have reduced corruption.

-

8/3/2019 Mathews, Knowledge, Power:Ignorance

16/27

Power/Knowledge, Power/Ignorance: Forest Fires and the State in Mexico 809

REGULATIONS: THE GENERATION OF DISCURSIVEPOWER AT THE CENTERRegulations and official rhetoric are both controlled by senior officialsand are rarely publicly criticized by subordinates, who at best avoid men-tioning them (as in the cases of firewood collection or fire control). Thusthe process by which new regulations are continually generated in Mexico

City serves to emphasize the formal and symbolic power of high levelofficials.Environmental regulations2l are developed according to a complexprocess of political consultation and administrative revision, most of whichtakes place in Mexico City. The highest law is the Mexican constitution,which justifies each subsequent environmental law, which must in turn be

clarified by a corresponding reglamiento (regulation) issued a year or twoafter the law, and largely drafted by the relevant bureaucracy.For example,SEMARNAP was responsible for drafting and issuing the reglamiento forthe 1997 forestry law.22Below this level lie the detailed Normas OficialesMexicanas-environmental control regulations ranging from fire control(SEMARNAP, 1997b), to the transport of forest products, to the exploita-tion of firewood (SEMARNAP, 1996). The process of developing new for-est regulations is highly centralized, and the actual process of writing aregulation requires extensive interministerial consultation and negotiation.This means that it is senior officials who negotiate the content of regu-lations, which inevitably come to reflect the knowledge of these officialsrather than the NGO and community representatives who are supposedlyconsulted. Riles (1998) has described how United Nations conference doc-uments are prepared in negotiations between states and NGO represen-tatives. The meaning of the conference text came to be defined by theconcrete practices of drafting new versions before and during the confer-ence, so that the relationship between the final text and its possible applica-tion in practice came to appear unimportant. A similar process appears tooccur in the generation of new environmental regulations in Mexico City,where the creation of regulations has a kind of autonomy from their possi-ble application. On one occasion, I asked a senior forestry official who wasresponsible for drafting three new norms how they were to be applied: heindicated that my question was misplaced because his office was responsi-ble for drafting norms, which were to be applied at state level. His answershows the degree to which the people who design regulations are insulated21Theprocess for developing regulations is similar in other fields.22Arce and Long describe a similar form of reciprocal ignorance between bureaucrats andpeasants in western Mexico (1993).

-

8/3/2019 Mathews, Knowledge, Power:Ignorance

17/27

810 Mathewsfrom the people who apply them (and from evidence that a regulation ismisguided or inappropriate).23A further reason for the generation of new regulations was given me byanother senior official, who stated that even unenforceable norms provideda means for federal bureaucracies to involve local officials and other actors,as the regulations provided a permanent reservoir of authority upon whichofficials could draw. A more cynical interpretation of the causes of over-regulation was given to me by a businessman friend in Mexico City, whosuggested that politicians deliberately created cumbersome regulations thateveryone had to evade or ignore to some extent, thereby rendering them-selves vulnerable to politically motivated prosecutions at a later date. Un-enforced regulations create an oppressive sense of guilt among those whoare not powerful enough to ignore regulations at will. In practice, most peo-ple lack the resources or skills to find out what the latest regulations are, andthe fear that government officials may suddenly invoke a hitherto unknownregulation dictates that people approach officials with considerable trepida-tion and dissimulation. This means that the discursive and practical powerof officials elicits corresponding tactics of evasion and silence from theirclients. For our present purposes what is of interest is the mutual ignorancethese strategies of evasion and dissimulation generate between officials andtheir clients.24

The fire control policies and conceptual categories of the forest ser-vice have been incorporated into popular practices in a few model forestcommunities where commercial forest management has displaced agricul-ture (Mathews, 2003), but in most cases they receive only lip service, asdemonstrated by the widespread use of fire and firewood by rural peopleacross Mexico. Most rural communities (those with commercially unattrac-tive forests) know little of the forest service and forest regulations beyonda general fear that a forestry official may fine them for cutting firewood orburning.

ILLEGAL FUELWOOD CUTTINGFirewood and charcoal production in Mexico is known to be at leastcomparable in quantity to all other industrial uses put together but thisuse of the forests is almost completely uncontrolled by the state, with onlyaround 1% of fuelwood consumption legally sanctioned and notified (Diaz

23Arce and Long describe a similar form of reciprocal ignorance between bureaucrats andpeasants in western Mexico (Arce and Long, 1993).24j am indebted for the term 'public secret' to Sally Falk Moore's description of internationaldevelopment discourse in West Africa (Moore, 2001).

-

8/3/2019 Mathews, Knowledge, Power:Ignorance

18/27

Power/Knowledge, Power/Ignorance: Forest Fires and the State in Mexico 811

Jimenez, 2000; SEMARNAP, 1997a). According to the official regulation,domestic fuelwood cutting may be carried out with no permit as long as noliving trees are cut (SEMARNAP, 1996). This regulation codifies an officialfiction allowing firewood cutters to argue that they are cutting only deadwood and forest service officials to concentrate on more rewarding areas ofwork.In Oaxaca in 2000, forest service officials continued to repeat the lowand incredible official figures for firewood production in public meetingswith leaders of forest communities, although these officials readily admit-ted to me in private that firewood consumption was many times greaterthan the official figures. The community leaders who attended these meet-ings similarlyknew that illicit firewood cutting was widely practiced, but re-mained tactfully silent, avoiding the embarrassment and potential troublewhich questioning official pronouncements would produce. Thus, the in-correct and low official firewood production figures were stated as a publictruth which was paralleled by a 'public secret' that they were incredible andincorrect;25 he tension between truth and secret was reconciled by normswhich prevented the low official figures from being challenged in public.

INSTITUTIONALIZING OFFICIAL IGNORANCEABOUT FOREST FIRES

The distance between public truth and public secret is much greaterin the case of fire than in the case of fuelwood. Officials and colludeto tactfully ignore traditional uses of fire, and forestry officials and ur-ban Mexicans are genuinely ignorant of the real reasons why rural peo-ple might use fire are (Rodriguez Trejo, 2003). Officials sympathetic to ru-ral people believed fires were due to poverty and ignorance, but no-one Italked with mentioned the prevalence or even the existence of controlledburning. At present, a small group of Mexican researchers (RodriguezTrejo, 2003) and allies from such international institutions as the NatureConservancy (Nature Conservancy, 2004), are well aware of the importanceof prescribed fire to maintain or restore protected areas in Mexico. How-ever, this is a very marginalised group which has been criticized by Mexicanand international conservationists for threatening to "mix the message"of fire suppression (Catterson et al., 2004). Conservation institutions and25The argument that the value of traditional knowledge about fire has been devalued by ac-culturation may be ubiquitous in bureaucratic representations of traditional uses of fire. Forexample in Northern Australia park managers stated that "... aboriginalculture has changedand is therefore inappropriate for Park management goals in habitat burning" (Lewis, 1989,p. 951).

-

8/3/2019 Mathews, Knowledge, Power:Ignorance

19/27

812 Mathewsforesters continue to need an "unmixed message" of fire suppression inorder attract funding for fire fighting and conservation policies. This meansthat those who would like to move away from strict protection and firesuppression must do so discretely. Even these fire researchers have yet topoint out the already existing widespread use of controlled fires by ruralpeople. Populist and anthropological support for traditional agricultural useof fire has made some headway within the forest service, but this has onlyserved to conceptually confine responsible uses of fire to the past, beforemodernization corrupted traditional indigenous knowledge, and formerlysustainable fire management practices are contrasted with present day ig-norance and recklessness (e.g., INDUFOR, 2000, p. 134).26The official discourse of fire as destructive has hampered all officialefforts to gather information about the size or impact of fires. Overdetailedregulations render most fire use 'illegal' and official figures about the areasof forest affected by fire report only fires which come to the attention of theforest service. In Oaxaca in 2000-2001 fires were recorded only if they wereclose enough to the city of Oaxaca to allow the forest service fire brigadesto intervene rapidly. More distant fires attracted official attention only ifthey were large and lasted long enough for fire brigades to arrive. The largenumber of agropastoral fires which were deliberately set and kept undercontrol were not recorded because the forest service had not been involved.Thus, the forest service is unable to gather or interpret information whichmight help it to distinguish between destructive and non-destructive fires.The forest service's policy of fire suppression is one of its main pro-grams and is a source of its legitimacy in the eyes of the urban Mexicanswho are by far its most influential political constituency. The forest ser-vice represents itself as the source of order and stability and depicts fire asthe source of the disorder it is supposed to prevent. The official discoursesurrounding fire suppression has been represented so consistently in offi-cial statements and newspaper accounts that urban Mexicans have largelyaccepted that fire is solely destructive and that it results from rural igno-rance. The real impact of the fire control regulations is not in direct fireprevention or punishment of burning. Rather, these regulations are part ofthe official discourse which justifies the forest service's authority by repre-senting the forests of Mexico as being at the mercy of destructive peasantfarmers.The view that fire is uniformly destructive is a political myth whichmid-level and field level foresters may disagree with, but which they cannotopenly challenge. Some Mexican foresters have long been well aware of26A new law is not enforced until it has an accompanying reglamiento (regulation) and thenecessary institutional changes are made. When there is a very rapid sequence of laws, stateand municipal level officials may decide to move slowly, on the grounds that by the time theyhave learned the content of a law, another will probably come to supercede it.

-

8/3/2019 Mathews, Knowledge, Power:Ignorance

20/27

Power/Knowledge, Power/Ignorance: Forest Fires and the State in Mexico 813

the negative ecological impacts of fire suppression in the United States, butthey feel that they cannot publicly question the official policy that all firesare destructive. As a young forestry researcher told me:

We foresters, know quite a bit about fire, but the people of the city, the politicians,criticize the use of fire a lot, so foresters have to do it in secret.

Foresters' technical knowledge of fire as a potentially benign force whichcould assist the regeneration of pine species coexists uncomfortably with anofficial fire discourse which depicts fire as totally destructive. For example,in a recent issue of the journal Forestal, the 2003 fire fighting program wasannounced, with a total budget of 350 million pesos and over 10,000 fire-fighters in federal, state, and military fire-brigades (Anonymous, 2003b).In the same number, an article discussed the decline of southern yellowpines in the United States as being the result of fire suppression policies(Anonymous, 2003a), and another article gingerly and discreetly referredto incipient programs of prescribed burns (Anonymous, 2003c).The conflict between official fire discourse and the practical knowledgeof field foresters gives rise to similar contradictions; for example, a forestryofficial in Oaxaca told me that most forest fires were superficial and did nodamage; later in the same interview he told me that forest fires were the"greatest threat to the forest." On the face of it this was a flagrant self-contradiction. How could most forest fires be superficial and do little dam-age and at the same time be such a threat? Part of the answer was that thefire scars left by light fires can provide access to disease causing organismsand reduce the commercial value of the tree. Light fires can also becomecrown fires and escape control. However, I suggest that this contradictionwas due to the tension between official fire discourse which could be ex-pressed publicly and 'local knowledge' of the biophysical impacts of forestfires, which could only be expressed privately. The simplification requiredby the political meaning of fire prevented the nuanced practical knowledgeof field foresters from percolating upwards through the forest service to af-fect official policies.This raises the question of whether a degree of practical ignorance isimposed upon officials as they progress up through the ranks of the forestservice. Certainly, some senior figures were well aware that not all fires aredestructive, but as we have seen, prescribed burning is a very marginalizedactivity. However, pronouncements in favor of fire control are pervasiveand budgets and manpower dedicated to fighting fires are incomparablygreater than those dedicated to controlled burning by forestry officials,whilst there is no budget at all for studying the actual burning practicesof ruralpeople.

-

8/3/2019 Mathews, Knowledge, Power:Ignorance

21/27

814 Mathews

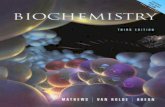

r __..~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~n

i ... .. .~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~.o - N ''4''a -a i*04 :s

Fig.1.SEMARNAPanti-fire oster.Caption eads"Andhowmanymorebirth-days do you want to celebrate? Take care of us, we want to live more. AvoidForestFires!

Senior officials are responsible for representing the forest service as aninstitutionwhichcan designand implementa systemof rules with whichnature is to be regulated; because they are unlikely to receive official evi-dence that rulesarebeing ignored,theycome to believe thatthe rulesareusefulandmeaningful, ven wheretheyknowof evidenceto the contrary.

-

8/3/2019 Mathews, Knowledge, Power:Ignorance

22/27

Power/Knowledge, Power/Ignorance: Forest Fires and the State in Mexico 815The practices by which they create new regulations and represent the for-est service in public events make the natural and social worlds envisionedby regulations much more immediate to them than the reality of firewoodcutting and widespread burning. Illegal firewood use is known as a fact pro-duced from an occasional report. However, there is no set of institutionsresponsible for controlling firewood use, no reports of firewood produc-tion are generated, and no public discussions of firewood production takeplace. This makes knowledge of firewood use rather distant and theoreti-cal, whilst knowledge of timber production is much more immediate andconcrete: voluminous reports cross the desk of officials responsible for in-dustrial timber production, management plans must be analyzed and ap-proved, officials must declare annual production figures and hope to in-crease them. Only the field foresters, who actually work in the forests,physically confront the evidence of widespread evasion of official firewoodcontrols.

CONCLUSIONI have argued that Foucauldian analyses of governmentality haveoveremphasized the ability of the state to produce new understandings ofself, and that by concentrating on official projects and official knowledge,they have reinscribed the concept of the state as a set of institutions whichbase their power upon forms of knowledge and calculation, and that theyhave paid too little attention to the real structures and cultures of state in-stitutions. In the case of Mexican forestry, the calculations and techniqueswhich are supposed to produce official power/knowledge have been sub-verted both by the internal culture of the forest service, and by the exis-tence of long-standing traditions of fire use which low level officials andruralpeople have simply concealed from official notice.As Nuitjens (2004) points out, critics of governmentality have concen-trated their attention upon the continuing power of preexisting traditionsand understandings of the state among the subjects of rule. The continuedrural fire use I have described in this paper further confirms these criti-cisms, and reaffirms the importance of mapping out institutional structuresand cultures. Far from producing new subjectivities and making rural peo-ple aware of themselves as ignorant and drunken fire users, official firecontrol efforts have bolstered the legitimacy of the forest service with urban

supporters, created symbolic capital for forestry officials, and taught ruralpeople how to represent themselves as morally upright firefighters in en-counters with the state. State power imposes the ways in which things mustbe done, but it often has little effect upon popular beliefs, and is ultimately

-

8/3/2019 Mathews, Knowledge, Power:Ignorance

23/27

816 Mathews

backed up by coercion (Sayer, 1994). Officials and their clients colludein the creation of 'public secrets' (see Moore, 2001), which both partiesbelieve to be untrue, but which must be asserted. The Oaxacan comuneroswho affirmed their allegiance to firefighting in meetings with the forest ser-vice were concerned with receiving subsidies from a government forestryproject, and made sure that continuing fire use was tactfully ignored. Thispoints to the importance of concrete institutions in producing new subjec-tivities; a free floating discourse of fire control alone is insufficient.A less commented upon weakness of governmentality studies has beenthe lack of attention they pay to the official acts of ignoring and collusionwhich maintain public secrets and official ignorance, both tactical and ma-terial. These ideas of secrecy, collusion and obscurity, and the movementbetween public secrets and private revelations are central to the ways inwhich state power is asserted by the fragmented (but conceptually unified)Mexican state. It is the daily practices of the Mexican forest service whichhave produced official knowledge and ignorance about the present activi-ties of foresters within the forest service, about the activities of ruralpeople,and about the past of the forest service itself.Ecological anthropologists have long sought to prove that natural re-source dependent peoples are not ecologically ignorant degraders of nature,but this kind of knowledge is not usable by hierarchical institutions wherehigh level officials seek to retain control of formal and discursive power.For example, the Mexican state is unlikely to be able to act upon improvedknowledge of fire management by peasant farmers and indigenous people;this knowledge has been repeatedly produced over the last century (Alcorn,1984; Nigh, 1975; Xolocotzi, 1959 (1987)) and just as frequently 'forgotten'because Mexican farmers hide their use of fire from the officials who wouldseek to control it. One part of the answer could be administrative decen-tralization, which would give local level officials the autonomy to act uponwhat they know; in fact, administrative decentralization is one of the centraltopics of contemporary Mexican political debate (Rodriguez, 1999; Wardand Rodriguez, 1999). Decentralization has, however, been more rhetori-cal than practical to date; the federal government has retained control ofalmost all significant revenue collection and distribution functions and re-sponsibility for the environment continues to be a federal responsibility.This has limited the power of state and local governments to alter forestservice policies and strongly suggests that official ignorance about naturewill continue to be generated in Mexico City.I do not think that official ignorance about fires and firewood useis because Mexico is corrupt or the forest service particularly weak ordysfunctional. On the contrary, given its limited resources SEMARNAP

-

8/3/2019 Mathews, Knowledge, Power:Ignorance

24/27

Power/Knowledge, Power/Ignorance: Forest Fires and the State in Mexico 817works quite well and has asserted some degree of control over the forestsof Mexico; it is simply that SEMARNAP functions rather differently fromthe rational/legal bureaucracy it claims to be, or the discursively powerfulinstitutions described by post-structuralist critics of development, wholargely miss the importance of bureaucratic structures and their internaldynamics. I suggest that the variety of forms of ignorance and knowledgeI describe may be present in other bureaucracies, in the first and the thirdworld, including international conservation and development institutions.Outside the environmental field, the same kind of investigation could bemade of almost any arena of state interest and activity. The conception ofthe state which claims authoritative knowledge is itself a cultural category.

Official power and official knowledge are often linked in academic un-derstandings of the state, so much so that power and knowledge appearinextricably linked. This is strange, because popular and vernacular un-derstandings of the state are much more ambiguous. Much of the schol-arship of the state seems to have accepted rather unreflectively that officialpower springs from official knowledge. This may be in part because mostacademics do not have to carry out the routine evasions of state power inwhich the very powerful and the very weak engage. Or perhaps academicsare culturally and socially closer to the government officials who design reg-ulations than they are to the people who evade them, so that they are takenover by the categories of the state and misrecognize the official ignorancewhich parallels official knowledge (Bourdieu, 1994, p. 35). I suggest that inreiterating the apparently obvious linkage between power and knowledge,poststructuralist scholars have misrecognized the official ignorance and theevasions and complicities which are characteristic of state power. As Mr.Bumble suggests, we should be suspicious of the idea that the state has eyesor that it learns through experience, and we should pay more attention tothe power struggles where officials and their clients navigate official knowl-edge and official ignorance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTSThis research was funded by the Tropical Resource Institute of theYale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, by an Enders Grantfrom the Yale Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, by the Yale Center forInternational and Area Studies, by a Switzer Fellowship from the Switzer

Foundation, by a Fulbright/Garcia/Robles fellowship, and by a DissertationResearch Grant from the NSF Program in Science and Technology Studies.My thanks to Professor Michael R. Dove for patiently reading an earlydraft, and also for being a principal investigator for this project, and toAmita Baviskar for her thoughtful comments on a short version of this

-

8/3/2019 Mathews, Knowledge, Power:Ignorance

25/27

818 Mathewsmaterial. I thank also my collaborators in Mexico, the communeros andauthorities of Ixtlan de Juarez and INIFAP and SEMARNAP officials inOaxaca and Mexico City (most of whom remain anonymous). I thank threeanonymous reviewers for their careful reading and insightful criticisms.

REFERENCESAlcorn, J. B. (1984). Huastec Maya Ethnobotany, Texas University Press, Austin.Anderson, B. R. (1991). Imagined Communities:Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Na-

tionalism. Verso, New York.Anonymous. (2003a). Breves, Forestal XXI (Enero-Febrero): 30.Anonymous. (2003b). En marcha la campaonfa nacional de protecci6n contra incendios fore-stales 2003. Forestal XXI (Enero-Febrero): 30.Anonymous. (2003c). Situaci6n actual de la investigaci6n: Incendios forestales en M6xico.Forestal XXI (Enero-Febrero): 36-38.Arce, A., and Long, N. (1993). Bridging two worlds: An Ethnography of Bureaucrat-PeasantRelations in Western Mexico. In Hobart, M. (ed.), An Anthropological Critique of Devel-opment: The Growth of Ignorance, Routledge, London and New York, pp. 177-208.Bourdieu, P. (1994). Rethinking the State: Genesis and Structure of the Bureaucratic Field.Stanford University Press, Stanford.Bowker, G. C., and Star, S. L. (1999). Sorting Things Out. Classification and Its Consequences.Massachussetts, Cambridge, MIT Press. 377 p.Calvino, M. (1916 (op.cit. Toro, 1981 (1945))). Boletin No. 4 del Departamento de Agriculturade Yucatan.Castillo Roman, A. (1996) Se atienden todas las demandas por ilicitos que daiian los recursos.El Nacional July, 16.Catterson, T. M., Cedeno Sanchez, O., and Lenzo, S. (2004). Assessment and Diagnostic Re-view of Fire Training and Management Activities Funded by USAID/Mexico from 1998-2003. USAID.Coronil, F. (1997). The Magical State,Nature, Money and Modernity in Venezuela, Universityof Chicago Press, Chicago and London.Craib, R. B. (2002). A Nationalist Metaphysics: State Fixations, National Maps, and theGeo-Historical Imagination in Nineteenth-Century Mexico. Hispanic American Histor-ical Review 82(1): 33-68.Crutzen, P. J., and Goldammer, J. G. (Ed.) (1993). Fire in the Environment: The Ecological, At-

mospheric and Climatic Importance of VegetationFires. Chichester, England: John Wileyand Sons.Diaz Jimenez, R. (2000). Consumo de lefia en el sector residencial de Mexico: Evoluci6nhist6rica de emisiones de C02 [M.S.]. Universidad Nacional Aut6noma de M6xico,M6xico.Dickens, C. (2001). Oliver Twist.ElecBook, London.Douglas, M. (1986). How Institutions Think. Syracuse University Press, Syracuse, New York.Dove, M. (1983). Theories of Swidden Agriculture and the Political Economy of Ignorance.Agroforestry Systems 1(1): 85-99.Dove, M. R., and Kammen, D. M. (2001). Vernacular Models of Development: An Analysisof Indonesia Under the "New Order." World Development 29(4): 619-639.Escobar, A. (1991). Anthropology and the Development Encounter: The Making and Market-ing of Development Anthropology. American Ethnologist 18(4): 658-682.Fairhead, J., and Leach, M. (2000a). Fashioned Forest Pasts, Occluded Histories? Interna-tional Environmental Analysis in West African Locales. Development and Change 31: 35-39.Fairhead, J., and Leach, M. (2000b). Misreading the African landscape: Society and ecology ina forest-savanna mosaic. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

-

8/3/2019 Mathews, Knowledge, Power:Ignorance

26/27

Power/Knowledge, Power/Ignorance: Forest Fires and the State in Mexico 819

Ferguson, J. (1994). The Antipolitics Machine. "Development," Depoliticization and Bureau-cratic Power in Lesotho. University of Minnesota Press.Ferguson, J., and Gupta, A. (2002). Spatializing States: Toward an Ethnography of NeoliberalGovernmentality. American Ethnologist 29(4): 981-1002.Foucault, M. (1991a). Governmentality. In, Burchell, G., Gordon, C., and Miller, P. (Ed.) TheFoucault Effect:Studies in Governmentality,University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp. 87-104.Foucault, M. (1991b). Truth and Power. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviewsand OtherWrit-ings. 1980 [1972]. Harvester Press.Galindo, P. L6pez-Perez, P., and Evangelista-Salazar, M. (2003). Real-Time AVHRR ForestFire Detection in Mexico (1998-2000). InternationalJournal of Remote Sensing 24(1): 9-22.Gerth, H. H., and Mills, C. W. (1958). From Max Weber:Essays in Sociology. Oxford Univer-sity Press, New York.G6mez Mena, C. (2003). 3/27/2003. Solicit6 a la Sagarpa que "decrete algun tipo de figurajuridica": Plantea la Conafor quitar subsidios a agricultores que quemen terrenos. LaJornada.Gonzalez, R. J. (2001). Zapotec Science. Austin, University of Texas Press, Texas.Gordon, C. (1991). Government Rationality. In, Burchell, G., Gordon, C., Miller P. (ed.). TheFoucault Effect:Studies in Governmentality,University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp. 1-51.Grindle, M. S. (1977). Bureaucrats,Politicians and Peasants in Mexico: A Case Study in PublicPolicy. University of California Press, Berkeley.Gutierrez, J. L. (1930a). Para prevenir y combatir los incendios de montes en la Repuiblicaesta Direcci6n ha estado organizando el mayor nuimeroposible de Corporaciones de De-

fensa Contra Incendios de Montes. AGEO: Asuntos Agrarios, Serie V Problemas porBosques.Gutifrez, J. L. (1930b). Se remite ejemplar del reglamento para constituir corporacion de de-fensa contra incendios. AGEO: Asuntos Agrarios, Serie V Problemas por Bosques.Haenn, N. (2004). Fields of Power, Forests of Discontent: Culture, Conservation and The statein Mexico, University of Arizona Press.INDUFOR. (2000). SEMARNAP: Plan estrategico forestal para Mexico 2020Helsinki,INDUFOR.Klooster, D. (2003). Campesinos and Mexican Forest Policy During the Twentieth century.Latin American Research Review 38(2): 94-126.Lewis, H. T. (1989). Ecological and Technological Knowledge of Fire: Aborigine versus ParkRangers in Northern Australia. American Anthropologist 91(4): 940-961.Li, T. (1999). Compromising Power: Development, Culture and Rule in Indonesia. CulturalAnthropology 14(3): 295-322.Lomnitz, L. (1982). Horizontal and Vertical Relations and the Social Structure of Urban Mex-ico. Latin American Research Review 17(2): 51-74.Lomnitz, L,. Mayer, L., and Rees, M. W. (1983). Recruiting Technical Elites: Mexico's veteri-narians. Human Organization 42(1): 2-29.Mares J. (1932). Se remite plan generalpara la Campana centra incendios de montes. AGEO:Asuntos Agrarios, Serie V Problemas por Bosques. p 6.Mathews, A. S. (2003). Suppressing Fire and Memory: Environmental Degradation and Polit-ical Restoration in the Sierra Juarez of Oaxaca 1887-2001. Environmental History 8(1):77-108.Mathews, A. S. (2004). Forestry Culture: Knowledge, Institutions and Power in MexicanForestry, 1926-2001. Ph. D. Thesis. Yale University, New Haven.Moore, S. F. (2001). The International Production of Authoritative Knowledge: The Case ofDrought Stricken West Africa. Ethnography 2(2): 161-189.Morris, L. (1998). Governing at a Distance: The Elaboration of Controls in British Immigra-tion. InternationalMigration Review 32(4): 949-973.Nature Conservancy. (2004). The Latin American and Caribbean Fire Learning Network.http://tnc-ecomanagement.org/IntlFire/.

-

8/3/2019 Mathews, Knowledge, Power:Ignorance

27/27

820 MathewsNigh, R. B. (1975). Evolutionary Ecology of Maya Agriculture in Highland Chiapas, Ph.D.Dissertation, Anthropology, Stanford University.Nuitjens, M. (2004). Between Fear and Fantasy: Governmentality and the Working of Powerin Mexico. Critiqueof Anthropology 24(2): 209-230.P6rez U. M. (2002). 1/18/2002. Productores de Campeche se movilizan ante oficinas deSagarpa, Semarnat y. Sedesol: Campesinos exigen cumplimiento de acuerdos y masapoyo. La Jornada.Pyne, S. J. (1993). Keeper of the Flame: A Survey of Anthropogenic Fire. In: Crutzen, P. J.,Goldammer., and J. G. (eds.) Fire in the Environment:Its Ecological, Climatic, and Atmo-spheric Chemical Importance. Chichester, England: John Wiley. pp. 245-266.Pyne S. J. (1998). Forged in Fire: History, Land and Anthropogenic Fire. In, Bale, W., (ed.)Advances in historical ecology, Columbia University Press, New York, pp. 64-103.Rodriguez Trejo, D. A. (2003). Fire Management Conflict Among Urban and Rural Popula-tions and Five Related Ecosystems in the Mexico City Forests. 3rd International WildlandFire Conference and Exhibition, Sydney, Australia.Rodriguez, V. E. (1999). La decentralizaci6n en Mexico: de la reforma municipal a Solidaridady el nuevo federalismo. Suarez, E.L. translator.Mexico City: Fondo de CulturaEcononica.Rose, N. (1999a). Powers of Freedom: Reframing Political Thought. Cambridge UniversityPress.Said, E. W. (1979). Orientalism. Random House.Sayer, D. (1994). Everyday Forms of State Formation: Some Dissident Remarks on "Hege-mony." In, Joseph, G. M., and Nugent, D. (eds.) Everyday Forms of StateFormation: Rev-olution and the Negotiation of Rule in Modern Mexico, Duke University Press, Durham,pp. 367-377.Scott, J. C. (1998). Seeing Like a State: How CertainSchemes to Improve the Human Condition

Have Failed. Yale University Press, New Haven and London.SEMARNAP. (1996). NORMA Oficial Mexicana NOM-012-RECNAT-1996, Que establecelos procedimientos, criterios y especificaciones para realizar el aprovechamiento de leiiapara uso domestico.: SEMARNAT.SEMARNAP. (1997a). Anuario estadistico de la producci6n forestal. M6xico D.F.: SEMAR-NAP. 120 p.SEMARNAP. (1997b). NORMA Oficial Mexicana NOM-015-SEMARNAP/SAGAR-1997Que regula el uso del fuego en terrenos forestales y agropecuarios, y que establee lasespecificaciones, criterios y procedimientos para ordenar la participaci6n social y de gob-ierno en la detecci6n y el combate de los incendios forestales.SEMARNAP. (2000). Evite Incendios Forestales: Y cudntos mas quieres CUMPLIR?Cuidanos! Oaxaca, Mexico: SEMARNAP, SEDAF.SEMARNAP. (2001). Estructura organica de SEMARNAP.SEMARNAT. (2001). Estructura organica de SEMARNAT.Simonian, L. (1995). Defending the Land of theJaguar. University of Texas Press, Austin.Sivaramakrishnan,K. (1994). Modern forests: Statemakingand environmental change in Colo-nial Eastern India. Stanford University Press.Tsing, A. L. (1993). In the Realm of the Diamond Queen: Marginality in an Out-of-the-Way-Place. Princeton University Press.Tyrtania, L. (1992). Yagavila: un ensayo en ecologia cultural. Mexico, D.F.: Universi-dad Aut6noma Metropolitana, Unidad Iztapalapa, Divisi6n de Ciencias Sociales yHumanidades.Ward, P. M., and RodrIguez, V.E. (1999). New Federalism, Intra-governmental Relations andCogovernance in Mexico. Journal of Latin American Studies 31(3): 673-710.Watts, M. (2001). Development Ethnographies. Ethnography 2(2): 283-300.Weber, M. (1978). Economy and Society. Berkeley and London: University of California Press.Winichakul, T. (1994). Siam Mapped: A History of the Geo Body of a Nation. Honolulu:University of Hawaii Press.Xolocotzi, E. H. (1959 (1987)). La Agricultura en la Peninsula de Yucatan. In, Beltran E. (ed.),Xolocotzia: Obras de Efrain Herndndez Xolocotzi, Universidad Aut6noma de Chapingo,Texcoco, Mexico, pp. 371-408.