Mapping State Cultural Policy: The State of Washington State Cultural Policy: The State of...

-

Upload

nguyennhan -

Category

Documents

-

view

215 -

download

1

Transcript of Mapping State Cultural Policy: The State of Washington State Cultural Policy: The State of...

Mapping State Cultural Policy:The State of Washington

J. Mark Schuster, editor

J. Mark Schuster, David Karraker, Susan Bonaiuto, Colleen Grogan, Lawrence Rothfield, and Steven Rathgeb Smith

Cultural Policy CenterThe Irving B. Harris Graduate School of Public Policy Studies

The University of Chicago

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Mapping state cultural policy : the state of Washington / J. Mark Schuster, editor.p. cm.

ISBN 0-9747047-0-91. Washington (State)—Cultural policy. I. Schuster, J. Mark

Davidson, 1950-F895.M375 2003306'.09797—dc22

2003024054

Photography and art credits. Front cover: “Seattle Public Art,” photograph by TimothyD. Lace, 1993, used with the permission of the photographer. Featured in the frontcover photograph is “Hammering Man,” a sculpture by Jonathan Borofsky, 1988, usedwith permission of the artist.

Back cover photographs, top to bottom: “Orcas Island Vista,” photograph by TimothyD. Lace, 1993, used with the permission of the photographer; “Chuba Cabra,” mask byRoger Robert Wheeler, 2000, used with permission of the artist; “Lisa Apple: In theMiddle, somewhat elevated,” photograph by Angela Sterling, 2001, used with permission ofthe photographer; “An Artist in His Element,” photograph of metal artist, ChrisHembree, by Darcy Van Patten, 2003, used with permission of the photographer;“Lewis and Clark Map 1803,” image by Nicholas King, public domain image providedby Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress; “Ezelle,” sculpture by Bruce andShannon Andersen, 2003, used with permission of the artists; “Seattle,” quilt by IvyTuttle, 1997, used with permission of the artist.

Printed in the United States.

© 2003 The University of Chicago, Cultural Policy Center

For more information or for copies of this book contact:Cultural Policy Center at The University of ChicagoThe Irving B. Harris Graduate School of Public Policy Studies1155 East 60th Street, #157Chicago, IL 60637-2745

Phone: 773-702-4407Fax: 773-702-0926Cultural Policy Center website: culturalpolicy.uchicago.eduHarris School website: Harrisschool.uchicago.edu

The Cultural Policy Center at The University of Chicago fosters research to informpublic dialogue about the practical workings of culture in our lives.

The Cultural Policy Center is housed in and funded in part by The Irving B. HarrisGraduate School of Public Policy Studies.

This project was supported through a grant from The Pew Charitable Trusts. The opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views ofThe Pew Charitable Trusts.

Graphic Design: Catherine Lange Communicationsii

Foreword

iii

to study and map the many and diversepublic agencies and public policies thatinteract with the arts and culture, and tounderstand their intersections andinteractions.

Mapping State Cultural Policy: The State ofWashington is the result of the trusts’partnership with Professor Schuster, hisco-authors and the Cultural Policy Centerat the Irving B. Harris Graduate School ofPublic Policy Studies, The University ofChicago. It was made possible, as well, bymany willing and generous participants in the State of Washington. By puttinglanguage and form to the full extent ofWashington’s cultural policy system, thisreport helps us to understand the rich and complex mix of agencies and non-government organizations engaged incultural policy at the state level. To allthose who care about the great variety ofcultural resources and activities in Washing-ton, we believe it offers new informationand insights that will be useful instrengthening culturally relevant statepolicies and assuring effective culturalsupport. We also believe that this reportprovides a powerful and easily adaptablemethodology for cultural policymakersoutside Washington who wish to engagein a similar process of state-level analysis.

The report itself can be a catalyst for allthose involved or interested in culture torevisit and expand their thinking aboutthe impact of government policies on the cultural activity in their own states.Where are there untapped opportunitiesfor alliances and collaborations among

In 1999, The Pew Charitable Trustslaunched an initiative to foster broaderpublic appreciation of and support fornonprofit arts and culture and their rolein American society. This initiative,Optimizing America’s Cultural Resources, waspremised on the idea that the develop-ment of beneficial cultural policiesdepended in part upon providing moreand better information on arts and cultureto policymakers. Because even the mostbasic information about cultural organiza-tions and activities was fragmented,incomplete, and difficult to find or use,we invested in an array of projects togather, analyze, and make available dataon American arts and culture.

Similarly, the many public policies influ-encing cultural activity, with the exceptionof those related to the establishment andfunding of preservation agencies andgrantmaking agencies such as arts andhumanities councils, have also been frag-mented and little understood. The trusts’initiative also focused, in part, on analyz-ing and disseminating information aboutpolicies that either explicitly or implicitlyinfluenced cultural activity, with a specificemphasis on state-level policies. We werefortunate in having J. Mark Schuster,professor of urban cultural policy at theMassachusetts Institute of Technology, asa partner in this work. Indeed, it wasProfessor Schuster who first pointed outto us the advantages of looking at states.Whereas most cultural advocacy hasfocused either on the federal culturalagencies or at the municipal level, statesoffer a hitherto unexploited opportunity

Map

ping

Sta

te C

ultu

ral P

olic

y: Th

e St

ate

of W

ashi

ngto

n

iv

agencies? How can cultural leadersenhance their “policy IQ” and help poli-cymakers improve their “culture IQ”?And, at a time when all states are feeling afinancial pinch, how can new insightsabout how cultural policies are developedand implemented assist states in increas-ing the efficiency and the effectiveness oftheir cultural commitments? In otherstates, as in Washington, policymakersmay not have a complete view of themany components of the cultural policylandscape. Therefore, it is imperative that cultural practitioners and supportersinvest the time and energy it takes tounderstand what their particular statesystem looks like. Only then will culture’sadvocates be able to engage in fullyinformed and productive dialogue withpolicymakers.

Marian A. GodfreyDirector, Culture ProgramThe Pew Charitable Trusts

Prelude

v

To understand more fully the attributes ofstate level cultural policy and with an eyeto providing a service to individual stateswishing to consider and reflect upon thefull range of their cultural programs andpolicies as a unified whole, the CulturalPolicy Center at The University of Chicagoand The Pew Charitable Trusts teamedtogether for a pilot project: “MappingState Cultural Policy.” This project wasinspired by the very successful precedentof the Council of Europe’s Program ofReviews of National Cultural Policies,which has provided the opportunity forsome eighteen European countries toarticulate and receive comment on theirnational cultural policies. This report isthe result of our attempt to apply a simi-lar model to the State of Washington.

J. Mark Schuster, project director,with David Karraker, Susan Bonaiuto,Colleen Grogan, Lawrence Rothfield,and Steven Rathgeb Smith

Cultural Policy Center at The Universityof ChicagoThe Irving B. Harris Graduate School ofPublic Policy Studies

In my work as a state arts agency director, I found that most legislators and governmentofficials thought of culture as something separatefrom everyday life and everyday policy. It wasdifficult to find vehicles and language to articulatethe cultural policies implicit in, for instance, poli-cies and programs for tourism, transportation,education, economic development and social services.It was even more difficult to shape an overallvision that could guide the specifics of the culturalimpacts of policy decisions related to projects suchas highways, tourism positioning, public education,or construction of state facilities. This project willprovide a framework to help define that culturalvision and help everyone involved in policy makingto understand that there are ways to shape lawsand programs that will benefit the public’s cultural prosperity.

Susan Bonaiuto, former director, New Hampshire State Council on the Arts

State level support for the arts, humanities,heritage, and allied forms of culture has,for some time, been an important sourceof direct government support to theseendeavors in the United States. Moreover,it is now widely recognized that not onlylegislation, but also the projects, programs,and policies of a broad set of state-levelagencies have an important impact on thecultural life of a state. State cultural agencies,and their grant-making programs in par-ticular, provide the most visible supportfor culture, but the combination of policiesand programs across state government isa much better indicator of a state’s culturalvitality and its commitment to developingthe cultural life of its citizens.

Table of ContentsM

apping State Cultural Policy: The State of Washington

vii

Chapter I: Mapping State Cultural Policy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1J. Mark Schuster

What is State Cultural Policy?What Do We Mean by “Mapping”?Why is State Cultural Policy of Interest?Conceptualizing State Cultural PolicyWhy Washington?How is Washington Different?On MethodologyOn MoneyA Guide for the ReaderA Research Agenda

Chapter II: Main Findings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21J. Mark Schuster

The Ecology of State Cultural PolicyStorylines

Chapter III: The Arts and State Cultural Policy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 39J. Mark Schuster, David Karraker, and Susan Bonaiuto

The Washington State Arts CommissionBuilding for the Arts, Office of Community DevelopmentThe Arts in EducationOther Offices and Programs in the Arts PortfolioObservations and Conclusions

Chapter IV: The Humanities and State Cultural Policy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 85Lawrence Rothfield and David Karraker

Humanities WashingtonThe Washington State Historical SocietyOther Offices and Programs in the Humanities PortfolioObservations and Conclusions

Chapter V: The Heritage and State Cultural Policy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 109David Karraker and J. Mark Schuster

The Office of Archaeology and Historic PreservationThe Heritage Corridors Program, Washington State Department of TransportationThe Washington State Historical SocietyCapital Projects Fund for Washington’s HeritageThe Eastern Washington State Historical Society/The Northwest Museum of Arts and CultureHumanities WashingtonThe Heritage CaucusState Heritage Policy from a Local Point of ViewObservations and Conclusions

Map

ping

Sta

te C

ultu

ral P

olic

y: Th

e St

ate

of W

ashi

ngto

n

viii

Chapter VI: The Land-Based Agencies and State Cultural Policy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 149Susan Bonaiuto

Cultural Policy Themes in the Land-Based AgenciesPolicies and Programs of the Land-Based AgenciesObservations and Conclusions

Chapter VII: Native American Tribes and State Cultural Policy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 173Colleen Grogan

Introduction and BackgroundAreas of Significant Tribal Influence on State Cultural PolicyState Policy that Promotes the Creation of Tribal Art and/or the Interpretation of Tribal CultureObservations and Conclusions

Chapter VIII: Behind the Scenes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 189J. Mark Schuster and Steven Rathgeb Smith

The Washington State Department of RevenueNonprofit Facilities Program, Washington State Housing Finance CommissionCorporate Council for the Arts/ArtsFund

Chapter IX: Observations and Theory — The Future of State Cultural Policy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 209Steven Rathgeb Smith

The Enduring Influence of Federal PolicyThe Politics of State Cultural Policy and its ImplicationsLessons Learned for National and State Cultural Policy

Postlude . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 219

Appendices . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 221InterviewsDocuments Consulted/CitedProject StaffProject Advisory Board

Mapping State Cultural PolicyJ. Mark Schuster

Chapter I

1

The second factor that has providedresistance to the articulation of culturalpolicy is that there has been a generalreticence to be more explicit about policyin a field in which it has been popular tosay that that policy is reactive rather thanproactive—as in, “We follow the fieldrather than lead it. We respond to theneeds of the cultural sector and its manyconstituent cultural organizations. Wehave no policy, we are reactive.” But thisstance is problematic in two differentways. On the one hand, it can be seen as a policy in its own right; on the other, ithardly provides a normative reason forpublic sector intervention through policy.

It is possible that all of state culturalpolicy is simply the result of lobbyingpressure put on the state by the variousinterests in the cultural field, but we arenot quite ready to accept this explanationas to why it might seem plausible that astate “has no policy.”

Our view is different. If policy is theintentionality—or, more precisely, the set of intentionalities—of programs thatseek to achieve particular sets of out-comes in a field of government activity,can it be useful to identify those inten-tions and make them explicit? To somedegree, of course, those intentions aremade explicit—in legislation, in policydocuments, in strategic plans, and inmission statements—but other suchintentions are less clearly spelled out.Thus, we believe that it is also necessaryto identify the implicit cultural policy ofany agency or program of government byinferring intentionality from actual practice.The actions that a state and its manyoperational entities take that affect thecultural life of its citizens, whether directlyor indirectly, whether intentionally or

What is State Cultural Policy?It would likely be impossible to find adocument entitled, Our State’s CulturalPolicy, on the shelf of any governor, anystate legislature, or any state agency in theUnited States. This is attributable to twoprimary factors. The first is the difficultyof drawing a boundary around what isconsidered “cultural.” Does one wish totake an anthropological view in which allof the activities of humankind—sharedtraditions, beliefs, and ways of life—areconsidered cultural? Or does one wish totake what seems to be the more traditionalAmerican view in which “culture” is usedmore as a synonym for “the arts” and“the-arts-and-culture” becomes oneword? It is all too easy to be drawn into adebate over the definition of the word“culture.”

But it seems to us that there is a usefuland reasonable middle ground. We propose to take advantage of what we claim is ageneral societal consensus around a moretightly delineated area of cultural activitiesand interventions, which ought to beconsidered as a whole. Put one way, weare interested in all the ways that the stateassists, supports, or even hinders thecultural life of its citizens. Put another,a state’s cultural policy can be usefullythought of as the sum of its activitieswith respect to the arts (including the for-profit cultural industries), the humani-ties, and the heritage. Thus, state policywith respect to the arts, state policy withrespect to the humanities, and state policy with respect to the heritage makeup the primary components of statecultural policy.

Map

ping

Sta

te C

ultu

ral P

olic

y: Th

e St

ate

of W

ashi

ngto

n

2

David Nicandri, director of the WashingtonState Historical Society, has captured thispoint nicely in his correspondence withus, and it is worth quoting his discussionof the metaphor at some length:

[M]apping is not value neutral. Mapping—creating names, typologies, characteristics, andidentities—though nominally scientific can have aset of concurrent values….[T]o take Lewis andClark as examples, there were multiple purposesto be found in their narratives and maps. Somewere explicit, conventional, and therefore obviousto the explorers themselves. Others werenot….[T]he creation of a map is still ultimately a matter of crafting perspective. The journals andmaps of Lewis and Clark say as much aboutthemselves as they do about the various objects oftheir observation, whether land, river, or people.Not knowing, perhaps any more than the Indianswho encountered Lewis and Clark did, what thefuture may contain as a consequence of thismapping study, I wanted to stipulate thisobservation in the project record.

This point is well taken, so let us begin bynoting our beliefs for the project record:

We see our work more as policy analysisthan as policy description, though framinga policy through description is certainlycritical to its analysis. We recognizethat the process of framing shapeswhat one ultimately sees.

We believe that there is value inmaking explicit what is often implicit.This facilitates and improves policydiscussion and debate.

We believe that choices are often made today simply because similarones were made yesterday and thatthere is value in stopping to askwhether other options have beenadequately considered.

We believe that particular attentionshould be paid to communication andcollaboration in policy making, but we do not believe that that necessarilyextends to a preference for centralizedbureaucratic control. It is important,we believe, not to confuse the two.And we believe that one must recognizethat communication and collaborationare not costless, particularly for smallagencies with few resources.

unintentionally, together constitute theeffective cultural policy of that state.Underlying these actions is a terrain ofintentions, some explicit and some implicit,and our goal here is to provide a descrip-tion and discussion of that terrain. This iswhy “mapping” is an appropriatemetaphor.

What Do We Mean by “Mapping”?While our goal has been, in part, todocument and to catalogue the elementsof the cultural policy of the State ofWashington, we have also endeavored todo something more. We have undertakento provide interpretations of that policyoffered by participants in the policyprocess, as well as to provide our owninterpretations of that policy. We haveraised questions; we have tried to pointout opportunities and pitfalls. We havehighlighted choices that have been madeand choices that consequently were notmade; we have tried to identify optionsthat were not recognized as choices andtherefore not considered. We have donethis not because we believe that the optionsnot chosen would have been preferable,but because we believe that informedchoice ought to be considered a valuablepart of ongoing policy inquiry and debate.

We chose the metaphor of “mapping”to capture the spirit of this intent. In anymapping exercise, the cartographer makeschoices: What should be included, andwhat should be left out? What should beemphasized, and how should that empha-sis be rendered? And, perhaps mostimportantly, whose map is it to be, andwhose map is it not to be? We understandthat we ourselves have made choices—choices as to what to emphasize andchoices as to what to pay somewhat lessattention to. As with any mapping exer-cise, if others had undertaken this exer-cise, they would have collected differentdata, and even if they had considered thesame data as we considered, they wouldhave drawn different maps. Indeed, it isthis attribute that makes mapmakingstimulating.

3

Chapter I: Mapping State Cultural Policy

but they also are home to a variety ofextra-curricular institutions that providepublic programming. We have chosen toinclude the latter, featuring a few exam-ples; we have also included the easilyseparable arts programs of the Office ofthe Superintendent of Public Instruction(elementary and secondary education),but we have not looked at the arts andhumanities curricula of the state collegesand universities. We have not expandedour inquiry to sports, even though manywould argue that sports are cultural (andeven though many countries have seen fit to include sports in their cultural min-istries, e.g., the Department for Culture,Media and Sport in the United Kingdom).

But part of our methodology was also tolisten during our interviews for cues as tohow Washington State might perceive theterrain of its own cultural policy. As aresult, we have ensured that our boundaryincludes the trustee agencies that arepublic-private hybrids (the WashingtonState historical societies), as well as organ-izations that operate at the state level and,arguably, have a statewide policy influ-ence, even though they are not state agen-cies per se (e.g., Humanities Washington).The cultural policies of the land-basedstate agencies also turned out to beimportant and distinctive—a componentof cultural policy that we had not quiteexpected at the outset; because of theirimportance, these agencies are consideredseparately in Chapter VI. Similarly, Washing-ton’s Native American tribes, functioningas sovereign governments, also needed tobe considered in relation to state-levelpolicy; they are addressed in Chapter VII.

Another component of mapping is thatcategories have to be constructed. Thishad led us to draw a basic distinctionbetween arts policy, humanities policy, andheritage policy. But these categories, whileuseful for organizing the chapters of areport, are somewhat crude and arbitrary.Many of the agencies we have studiedbelong in more than one of these cate-gories; occasionally we have split ourdiscussion of the agency where it seemedthat that split would help clarify the

We believe that public agencies that clearly articulate the goals andobjectives of their programs andcarefully monitor progress towardthose goals and objectives will have,and should have, an advantage in mak-ing their claim on public resources. Yethere, too, there are costs associatedwith articulation, monitoring, and eval-uation, and trade-offs are inevitable.

We believe that there is considerablebenefit embodied in the American sys-tem of public policy, which delegatesimportant components of publicpolicy implementation to quasi-autonomous agencies and to nonprofitorganizations, but we also believe thatone can learn important lessons fromother ways of organizing the ecologyof public policy.

And, finally, we believe that a map ofone state’s cultural policy can be bestunderstood once one has an atlas ofsuch maps. The fact that the currentstudy comprises the first such mapmust be kept in mind when consider-ing its implications. Ideally, we wouldbe able to compare and contrast cul-tural policy maps of five or six (ormore) states, states with different con-ceptions of, and structures for, theircultural policy. Only then would themost valuable conversation be possi-ble, one that would draw on multipleexperiences in varying circumstances.But one has to begin somewhere.

As with any map, boundaries have to bedrawn. In this report we have includedthe visual and performing arts; we haveincluded the cultural industries to theextent that state cultural policy inWashington touches upon them; we haveincluded the heritage (not only the builtheritage but also the movable heritage aswell as the musical, oral, and written tradi-tions of the state); and we have includedthe humanities as they are funded andpracticed in public by and for the publicrather than for students or researchers.Education poses something of a bound-ary problem. The state universities havearts and humanities programs and curricula,

Map

ping

Sta

te C

ultu

ral P

olic

y: Th

e St

ate

of W

ashi

ngto

n

4

For fiscal year 2003, state legislaturesappropriated $353.9 million for the statearts agencies, which also received an addi-tional $23.5 million from other stategovernment sources (e.g., transfer fundsand public art money from state capitalbudgets).2 The appropriations for theNational Endowment for the Arts, on theother hand, were $116.5 million, of which$95.8 million was dedicated to grant mak-ing. Of this amount, $33.3 million waspassed through to the states.3 Thus, evenin a year in which state money declinedsubstantially, state support for the artsthrough state arts councils was still morethan 3.2 times direct federal support forthe arts through NEA. Taking transfersfrom NEA to the states into account,state influence over direct arts expenditurewas even higher. We argue elsewhere inthis report that drawing an analyticboundary narrowly around arts agenciesin this way can be misleading, but herethis simplified example makes the pointdramatically.

By contrast all of the state humanitiescouncils are private, nonprofit organiza-tions rather than state agencies. Whilethey receive support from the federalgovernment, they do not necessarilyreceive support from their respective statelegislatures. By 2002 the total income forstate humanities councils had grown to$59.9 million; federal money accountedfor $32.4 million (54 percent) of thisamount, while state funding accounted for$11.5 million (19 percent). In fiscal year2002, the appropriations for the NationalEndowment for the Humanities were$124.5 million—$18.4 million for agencyadministration and $106.1 million forgrants and programs. Of this amount,$31.8 million was passed directly throughto state humanities councils and regionalhumanities centers.4 But the combinedrevenue sources of the state humanitiescouncils are only part of the picture; forexample, all states make substantial contri-butions to the humanities throughhumanities programs at state colleges anduniversities, an expenditure that has nofederal equivalent.

agency’s activities. At other times, we have settled for discussing the agency inthe context of one of these categorieswhile recognizing that it also touchesupon other fields of cultural policy.

Why is State CulturalPolicy of Interest?The conceptualization of “cultural policy”as a separate field of public policy is arelatively recent phenomenon, particularlyin the United States where there has tradi-tionally been a fear of uttering this phrasewith all of its dirigiste implications.1 Todate, the limited cultural policy inquirythat has been undertaken in the UnitedStates has focused either on the nationallevel, which is a natural entry point forresearchers and policy analysts movinginto a field for the first time, or on thevery local level, which lends itself to fine-grained case studies of particular institu-tions or places.

Internationally there is no shortage ofstudies of national cultural policy. By com-parison, much less attention has been paidto the policies of intermediate levels ofgovernment—e.g., state policy in theUnited States and Australia, provincialpolicy in Canada, Länder policy inGermany and Austria, canton policy inSwitzerland, the policy of the comunidadesautónomas in Spain, or policy as it playedout through the regional arts boards inEngland. But there are good reasons tobegin to turn more analytical attentiontoward government cultural policy, andparticularly toward the cultural policies ofintermediate levels of government:

Direct support for the arts at thestate level is now—and has beenfor some time—a more importantsource of direct government aidto the arts in the United Statesthan is direct support at thefederal level. This may also betrue for the humanities and theheritage, but definitive data areharder to come by.

1 This section of this report isbased on J. Mark Schuster,“Sub-National CulturalPolicy—Where the Action is?Mapping State Cultural Policyin the United States.”International Journal of CulturalPolicy, Vol. 8, No. 2, 2002,181-196.

2 These figures include thebudgets of arts councils in special jurisdictions(American Samoa, PuertoRico, Guam, the VirginIslands, the NorthernMarianas, and Washington,D. C.).

3 The National Endowmentfor the Arts is currentlyobliged to pass along 40 per-cent of its program budget tothe state arts agencies.

4 The discrepancy between thefigures of $32.4 million and$31.8 million may be due toincome from other federalsources or to errors inbudget estimation.

Increasingly, cultural programsand projects are being adopted topursue a wide variety of societalaims (economic development,cultural tourism, interventionwith youth at risk, etc.), aims thatare more likely to be pursued atthe state and local levels becauseof their closer relationship to theconstituencies that are mostlikely to be affected.

These demands for improved and increasedcultural services and opportunities aremuch more likely to be expressed at thestate and local levels than at the nationallevel (except in the service of internationalrelations and diplomacy). Moreover, thepossible benefits from instrumentalizingculture are more likely to be articulatedlocally—e.g., heritage as a lure to culturaltourism. Thus, some elements of culturalpolicy may have been accorded a higherpriority in the states’ policy agendas thanhas previously been the case.

Government’s cultural agenciesand programs are increasinglybeing expected to exhibit greaterlevels of accountability andgreater levels of effectiveness.

In comparison to other fields of publicpolicy, government cultural policy has nottypically been subjected to the same levelof policy analysis and evaluation. Somewould say that the sector has been pro-tected from such inquiries because incultural policy goals and objectives aredifficult to measure, thereby frustratinganalysis and evaluation. But others wouldsay that the lack of insistence on analysisand evaluation has been more the resultof the relative size of the sector: it wastoo small (in policy terms) to pay muchattention to.

Recently this has begun to change.Criticisms of government cultural policy,particularly government arts funding, haveseemed to feature disagreement over pub-lic values, but they have also contained astrong measure of questioning about theeffectiveness of government’s involve-ment in the arts and culture. The phrase

Direct expenditure on the heritage andhistoric preservation, on the other hand,may well be less significant at the statelevel than at the federal level, though here,too, large-scale investment in heritage facili-ties, preservation, and history museumsmay tip the balance in favor of the states.

Finally, it is important to realize thatmuch of the direct support at the statelevel—particularly in the arts and historicpreservation—is required by the federalgovernment as a match to federal fundsthat are distributed to the individualstates. Some states only barely meet theminimum matching requirement (andsome do not even achieve that level), butothers appropriate amounts that exceedthe minimum matching requirement. Inrecent years there has been considerable(and successful) pressure to increase theproportion of federal funds that is passedthrough these state agencies, resulting in afurther increase in the amount of moneyavailable to be distributed at the state levelaccompanied by a higher expectation forstate-level matches.

The move toward delegation,devolution, and decentralizationin government policy makingand implementation has made itmore important to understandhow policy actually plays out atlower levels of government.

It is clear that the federal government isendeavoring to move many of the activitieshaving to do with cultural policy to thestate and local levels. Pass-through require-ments for the National Endowment forthe Arts provide increased resources tothe state arts agencies, and the Departmentof the Interior uses its system of statehistoric preservation officers to providean important portion of the work in thenomination of properties to the NationalRegister of Historic Places and in theadministration of various grant programsand rehabilitation certification programs.

5

Chapter I: Mapping State Cultural Policy

Map

ping

Sta

te C

ultu

ral P

olic

y: Th

e St

ate

of W

ashi

ngto

n

6

Federal Mandates,Regulations, Grants

Fund

ing

Grants,Lobbying

Lobb

ying

Lobb

ying

Directives Lobbying,Inform

ation Le

gislatio

n

Lobbyin

g,Inform

ation

Influence

Lobbyin

g, Informatio

n

Lobbying,Information

Funding,Legislation

Mim

ic

Avai

labl

e To

ols (

Ince

ntive

s, R

egul

atio

n, In

form

atio

n, P

rope

rty R

ight

s, P

ublic

Ope

ratio

n)

Avai

labl

e Ins

titut

iona

l Arra

ngem

ents

(Pol

icy S

urro

gate

s, Go

vern

men

t Age

ncy,

QUAN

GOS,

Par

tner

ship

s,etc

.)Al

tern

ative

Inst

itutio

nal A

rrang

emen

ts (A

genc

y Its

elf,

Othe

r Non

prof

its, e

tc.)

Avai

labl

e Re

sour

ces (

Cash

, Per

sonn

el, C

apita

l)

Avai

labl

e To

ols (

Nonp

rofit

Ope

ratio

n, In

cent

ives)

Availability of all threeelements shaped by

State Legislature andState Courts

Inte

nded

Targ

ets

Inte

nded

Out

com

esAc

tual

Out

com

es

Inte

nded

Targ

ets

Inte

nded

Out

com

esAc

tual

Out

com

es

Inte

nded

Targ

ets

Inte

nded

Out

com

esAc

tual

Out

com

es

Inte

nded

Targ

ets

Inte

nded

Out

com

esAc

tual

Out

com

es

Prog

ram

APr

ogra

m B

Prog

ram

CPr

ogra

m D

Fede

ral a

nd R

egio

nal A

genc

ies

Non-

gove

rnm

enta

l Co

nstit

uenc

ies

Gove

rnor

’s Of

fice

Stat

e Le

gisla

ture

Stat

e Ag

enci

esSi

ster

Agen

cies

Nonp

rofit

Age

ncie

sFu

nctio

ning

as P

olic

y Age

ncie

s

Figu

re I.

1: A

Con

cept

ual D

iagr

am o

f the

Eco

logy

of S

tate

Cul

tura

l Pol

icy

Internal Policy Influences

External Policy Influences

PolicyChoices

7

Chapter I: Mapping State Cultural Policy

7

directed—because they will benefit fromhaving access to an increasingly transpar-ent and effective system of culturalsupport and from knowing what opportu-nities are available at the state level inwhichever agency they happen to reside.

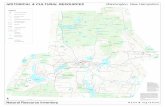

Conceptualizing State Cultural PolicyBefore proceeding into the field to mapstate cultural policy in Washington, weneeded a set of common reference pointsfor that inquiry. Most important to ourearly thinking was a conceptual diagramof the ecology of actors involved incultural policy at the state level (FigureI.1). Equipped with this diagram and arelatively standard model of public policyimplementation, we would document thepolicy linkages, policy influences, and pol-icy choices in Washington State.

In summary form, the story suggested by this diagram and the model of publicpolicy making that is embedded in it is the following:

Policy is the intentionality behind thecollection of programs that areintended to achieve a particular set of outcomes.

Policies may be explicit—in which case they should be able to beobserved through existing docu-ments—or implicit—in which case they should be able to be inferredfrom the statements and actions ofthe agency.

Policies may be espoused or de facto. The difference should be able to be detected with carefulinterviewing.

A number of influences are brought tobear on policy, e.g., funding, directives,legislation, regulations, political influ-ence, lobbying, the behavior of sisteragencies, and federal rules.

Policy is implemented through anecology of policy actors, includingagencies, programs, and a wide

“value for money” has become an impor-tant touchstone for reconsiderations ofgovernment’s cultural programs. This is atrend that the field can hardly afford toignore. If a claim is being made on thepublic purse—as it is in most manifesta-tions of public policy—then the rationalefor that claim has to be made clear.

Taken together, these factors suggest that,whether or not it has been articulated as“state cultural policy,” this type of policyhas become an increasingly importantlocus of interest for those who are con-cerned with the health and stability of thearts, culture, and humanities in the UnitedStates, as well as with the overall qualityof American life. It has also been anincreasing locus of attention for thosewho would have us focus on the effective-ness of public policy. Yet this rise in theimportance of, and attention to, policiesrelated to culture at the state level has notgenerally been accompanied by a similarlyevolving understanding of the culturalpolicy system that has developed withineach state. In effect, cultural policy at thestate level has been the sum total of themore or less independent, uncoordinatedactivities of a variety of state agencies and allied organizations and institutions.The extent to which these entities pursuecomplementary aims or collaborate is notwidely understood, nor is there a clearsense of what types of state policysystems enable or foreclose variouscultural initiatives.

What seems to us to be clear is thatinformed public policy, with a sense ofcurrent initiatives, available and potentialresources, identified opportunities, visible gaps,and nodes of conspicuous effectiveness is anincreasingly important goal to pursue. It is important to the front line culturalagencies because the pressure is on themto be more and more focused on theeffective allocation of public resourcesand more and more creative about ways inwhich to take advantage of cross-agencycollaborative opportunities. And it isimportant for the “targets” of culturalpolicy—those at whom cultural policy is

Map

ping

Sta

te C

ultu

ral P

olic

y: Th

e St

ate

of W

ashi

ngto

n

8

Four PremisesThough we tried to begin our fieldworkwith a tabula rasa, it is fair to say that fourimportant premises informed ourapproach from the beginning, and, thus,they deserve to be made explicit:

Many more agencies than thosethat are commonly understood to be the “cultural agencies”are involved in cultural policy.

All states have an arts council, a humani-ties council (though these are all privatenonprofit organizations), a state historicpreservation officer, and one or morehistorical societies. But it is also typicalfor state cultural policy to be delegated to state agencies beyond this core groupand/or to outside organizations and insti-tutions, each with related but distinctlydifferent notions of its role and its aims.Moreover, it is also increasingly commonfor other state agencies to create culturalprograms linked directly to their day-to-day operations.

Thus, we expected to find evidence ofcultural policy in many different agencies,departments, offices, and programs scat-tered throughout the state’s bureaucracy(in the event we were to discover that the land-based agencies in particular, suchas the Washington State Parks andRecreation Commission, the Departmentof Natural Resources, the Department ofAgriculture, and even the Department ofTransportation, among others, wereinvolved in activities that could bedescribed as cultural policy). In addition,we expected to find examples of policybeing delegated to independent or semi-independent entities whose actions weresimilar to and complemented statecultural policy but who were not solelywithin the orbit of state government.(Humanities Washington and theWashington State historical societiesturned out to be cases in point.)

variety of other public, semi-public, and private organizations.

Policies are translated into actionthrough programs.

Programs are composed of threeprimary elements:

They make use of the generic toolsof action that are available to thegovernment: government owner-ship and operation; incentives;regulation; information; and thedefinition, invention, and enforce-ment of property rights.

They draw upon available resources,e.g., cash, personnel, capital, andinformation.

They are designed with a particularinstitutional arrangement, e.g., directoperation by a state agency, use ofan external organization as a policysurrogate (through contracting or grant-making), or the establish-ment of a quasi-autonomous non-governmental organization(QUANGO), a government author-ity, or some other type of arm’slength agency.

The tools, resources, and institutionalarrangements that are available topolicy actors are, themselves, subjectto policy. Any particular policy actormay have access to a restricted set ofelements because of policy constraintson their actions.

Programs have intended targets (individu-als, groups, or organizations whosebehavior is intended to change as aresult of the intervention) and intendedoutcomes, e.g., increased participation,improved financial stability. Actual out-comes are often different from intendedoutcomes.

The importance of Figure I.1 wastwofold: it gave us a framework aroundwhich to construct our field interviewsand research, but it also revealed thecomplexity that we were likely to find inthe field.

an important impact on cultural policywell beyond the boundaries of what one would normally consider to be statecultural agencies and far beyond theboundaries of the traditional grant-making programs of state arts agencies.

Why Washington?Many have asked us why Washington waschosen as our pilot state.

Is it a model for state cultural policy thatwe hope to see replicated elsewhere? Hasit made mistakes that other states oughtto avoid? Does it have interesting attrib-utes that suggest it as the first state tostudy in this way? Does it fit into a broaderset of case studies that would comprise acomparative study?

We had no reason to believe that wewould—or would not—find a modelpolicy system in the State of Washington.Nor did we have any prior indication ofsuccesses or mistakes. We believed thatany state would have interesting attributesthat would make its cultural policy worthstudying, so that did not make Washing-ton unique. But, of course, we werehopeful that Washington would be thefirst step in a more broadly comparativestudy in which we could look at states of different types (e.g., states with a cen-tralized office of cultural commissionerversus states such as Washington with nosuch central bureaucratic coordination).

In truth, the answer is a bit more prosaic.In searching for a state in which to con-duct the first such mapping exercise, werealized that we had to find a state whoseagencies would be interested in receivingand reflecting upon the results of such astudy and whose agency heads wouldopen up their agencies to us, encouragingtheir staffs to participate. We would needto avoid, at least in the first instance,states in which cultural policy had becomeso politicized that there would be very lit-tle interest in introspection and reflection.As we discussed the choice of state withour project advisory board and others,the State of Washington began to bementioned more and more often. It was

In such a policy context, it is notcommon to think of the aggre-gate of these agencies, institu-tions, actions, and policies asconstituting a conceptual whole.

Reliance on multiple agencies andmultiple programs stacks the deck againsta coordinated policy. It makes policydifficult to articulate and makes it difficultfor policy agencies to move in the samedirection. Yet, each component of thesystem can be understood to be imple-menting its own form of cultural policy,and together they constitute the effectivecultural policy of the state.

Much of state cultural policy isimplicit rather than explicit,being the result of actions anddecisions taken withoutexpressed policy intention.

We expected that few of the agencies weinterviewed would have adopted explicitpolicy documents to guide and informtheir work. Instead, we would have toconsider their programs and actions in an attempt to infer their policy fromthose activities.

Much of state cultural policy isindirect rather than direct, beingthe result of a wide variety ofinterventions beyond direct oper-ation or direct financial support.

We expected that we would find culturalpolicies well outside of the culturalagencies. We had good reason to believe,for example, that a large component ofcultural policy would be embedded in var-ious components of tax law, particularlyin the form of tax exemptions.

Taken together these premises led to a net that had to be widely cast. We expectedstate cultural policy to be complex, goingwell beyond the boundaries of state artsagencies to include state humanitiescouncils, historical societies, historicpreservation agencies, community devel-opment initiatives, parks and recreationcommissions, and many other agenciesand programs. Legislation, funding,projects, and programs would each have 9

Chapter I: Mapping State Cultural Policy

Map

ping

Sta

te C

ultu

ral P

olic

y: Th

e St

ate

of W

ashi

ngto

n

10

Washington. For them, the key questionsare: What can be learned from such amapping exercise? What might it highlightabout current policy practice? What doesit suggest might be done differently?

But to interpret it well, this report mustbe understood as an attempt to documentand understand the cultural policy of oneplace at one point in time. The impor-tance of timing is clear. As we conductedour interviews the policy framework keptshifting, particularly as the cultural policysystem adjusted to changes in the state’sbudget. (Two rounds of budget cuts wereannounced during the course of ourwork, the first a relatively minor adjust-ment to the second year of the 2001-2003biennial budget when it became clear thatstate revenues were declining and thesecond a much more major decline in theproposed 2003-2005 biennial budget.)Thus, large portions of what we havedocumented in this report may soon fallvictim to budget cuts (if they have notalready done so). If we had looked at adifferent two-year period, what we wouldhave seen would have differed, perhaps inunknowable ways.

Timing has another importance as well.Even though the policy terrain was shift-ing as we did our research, what is pre-sented here is essentially a snapshot ofWashington’s cultural policy at onemoment in time. For the most part, wehave not documented trends.

Finally, the importance of characteristicsunique to the selected state should not beunderestimated. This is, of course,immediately apparent when one thinksabout the extent to which one might beable to generalize about state culturalpolicy from the case of one state.Consider, for example, the differencesthat one might observe if one were tocompare a state that implements itscultural policy through a variety of semi-independent cultural agencies (e.g., Wash-ington and many others) with a state thatgathers these diverse cultural activitiestogether in a single agency, perhaps with acabinet-level cultural commissioner (e.g.,Iowa, Louisiana, New Hampshire, New

widely felt that the key agency headswould be receptive and encouraging, andthat has indeed been the case.

In November 2001 Kris Tucker, theexecutive director of the WashingtonState Arts Commission, convened ameeting at her offices at which we wereinvited to pitch this project to representa-tives of ten or so state agencies. No onein that room (least of all ourselves) knewwhat a “Map of State Cultural Policy”was and certainly none of them came tothat meeting with the view that they needed“one of those.” But a generous spirit andopenness to inquiry permeated the meet-ing. We were challenged to launch an evenbroader and deeper inquiry than we hadenvisioned, and we were promised opendoors and collaborative support, both ofwhich we have received in great measure.

That initial meeting at which the projectwas proposed was a harbinger of what wewould find in the field; some of the par-ticipants in that meeting remarked that itwas the first time in their experience thatsuch a group of agency representativeshad ever met in the same room togetheraround their common interest in andcommitment to “cultural policy.” If thatphrase was surprising to some of thosewho gathered that day, the notion thatthey were involved in the same businessturned out to be less so. We would like tothink that this project, even from its earli-est days, has provided an impetus for thecultural agencies and programs of thestate to work more collaboratively, to havea better sense of how to integrate theirpolicy activities across domains, and tohave an opportunity to engage in a policyconversation that could occur outside ofthe boundaries of their own agencies. Butit was pointed out to us from the verybeginning that collaboration entails choices,particularly choices about the allocation ofscarce agency resources, and it needs tobe adequately demonstrated that such aninvestment of agency resources will ulti-mately be rewarded.

We expect that the primary beneficiariesof this report will be those who areengaged in cultural policy in the State of

starkly with the much more sparsely pop-ulated rural and agricultural counties, par-ticularly to the east of the Cascades; theyrange from only 3.4 to 51 people per sq.mile. Spokane County, which serves as thehome of the “inland empire” and is theregional hub for nearly all of the agricul-ture, livestock-raising, and mining activi-ties in the state, is the eastern exceptionwith 237 people per sq. mile.

Early settlers came largely from theMidwest along the Oregon Trail, and itwas not until the first quarter of thetwentieth century that foreign immigra-tion produced substantial populationgrowth; large numbers of Scandinaviansand Canadians migrated until strict quotaswere imposed in the 1920s. At this point,Washington had a population of approxi-mately 1.4 million. Tremendous growthtook place after World War II with theexpansion of international trade (and theemergence of Boeing and the aerospaceindustry), and then again in the 1970s and1980s. By 2001, the state had reached apopulation of just under 6 million people.That number reflects a 21 percent increasejust between 1990 and 2000. At the turnof the twenty-first century, 1.27 millionpeople (just 22 percent of the population)resided east of the Cascades. Growththroughout the state has slowed substan-tially during the past five years, and aslower growth rate is projected for thenext several years. Most of the populationgrowth remains concentrated in the west,with the large Puget Sound counties andClark County accounting for 72 percentof the state’s population increase in the last decade. This trend is predicted to continue.

Well over half the population of Washing-ton now lives in the Puget Sound area(primarily in King, Pierce, and Snohomishcounties). With the highest per capitaincome in the Northwest, this prosperousregion ranks twenty-fifth when comparedwith the rest of the nation’s regions witha per capita personal income that is more than 50 percent higher than the nationalaverage. Over the past few decades,this region has developed a substantial

Mexico, Nevada, and West Virginia,among others).5 But this is also true whensimply attempting to understand what ishappening in a single place and why it ishappening. Each state is rather different,and in order to understand the culturalpolicy of that state it is important tounderstand those differences.

How is WashingtonDifferent?There are many ways in which one statediffers from another, and we certainlyhave not attempted to identify all of thosecharacteristics for the State of Washington.What is most important, for our purpos-es, however, is how those characteristicsare likely to impact cultural policy. As wehave discussed the results of our field-work and have debated how best tointerpret those results, we have foundourselves making repeated reference toseveral characteristics that seem particu-larly important.

To set the stage, a brief overview of thedemographics of Washington is helpful.

The physical terrain and climate do muchto define what is distinctive aboutWashington, and these are among themost important factors that have attractedpeople to live and work there. Washingtonhas two very distinct geographical regionsseparated by the Cascade Range. To thewest is lush forest and gentle terrain slop-ing to the Pacific—a region with heavyrainfall where lumber and fisheries oncedominated. To the east of the Cascades isthe large, flat and semi-arid ColumbiaBasin that is primarily agricultural, thanksto an elaborate and carefully plannedirrigation and waterway infrastructure.

The majority of the state’s population isurban and is clustered in a densely peo-pled swath running along a north-southline through Puget Sound, including KingCounty with 817 people per sq. mile;Pierce County 418; Clark County 549,and Snohomish County 289. It is also inthese few counties that one finds, notsurprisingly, the greatest commercialdevelopment in the state. This contrasts 11

Chapter I: Mapping State Cultural Policy

5 See, for example, Lisa Wax,1994 State Arts Agency Profile(Washington, D.C.: NationalAssembly of State ArtsAgencies, January 1995).

Map

ping

Sta

te C

ultu

ral P

olic

y: Th

e St

ate

of W

ashi

ngto

n

12

couple more had median householdincomes that were just slightly lower),reflecting what many perceive as a funda-mental economic difference between theeastern and the western parts of the state.But these numbers can also be under-stood in another way: rural counties inboth sections of the state lag considerablybehind urban counties, indicating that theunderlying economic disparity may bemore rural v. urban than east v. west.

Racial minorities comprise just under one-fifth (18.2 percent) of the population,up from 13 percent in 1990.7 A relativelylarge percentage of Washington’s popula-tion is of Asian descent: 5.5 percent ascompared to a national average of 3.6percent. At the middle of the nineteenthcentury Washington was home to around100,000 Native Americans belonging tomore than 100 separate tribes; todayNative Americans comprise 1.6 percent ofthe state’s population (just under twice thenational average of 0.9 percent). Hispanicresidents make up 7.5 percent ofWashington’s population, a percentagethat is lower than the national average of12.5 percent. Similarly, Blacks or AfricanAmericans comprise only 3.2 percent ofthe population, as compared to a nationalaverage of 12.3 percent.

Beyond these demographic factors, thereare a number of other characteristics ofWashington that may well influence theprofile of state cultural policy:

Washington is a young state, andthe state is still growing, result-ing in an emphasis on capitaldevelopment.

In other, older states the cultural infra-structure may be more highly developed.To the extent that this is true, one wouldexpect to see more investment in culturalinfrastructure in Washington than else-where. Atypically among states, Washing-ton has capital grants programs in boththe arts and heritage, and a considerableinvestment has recently been made in newmuseums, particularly in Tacoma.

technology sector (with Microsoft and themany smaller companies it has spawned),and it continues to diversify into areas likebiotechnology and information technology.This is in addition to aerospace andaircraft, long established areas of strengthin the Washington economy.

The rest of the state is, by contrast, muchmore sparsely settled and much less eco-nomically prosperous. In the past twenty-five years, the timber industry—long amainstay of the Washington economy—has been radically downsized. This is dueto the dwindling supply of old growthforest, competition from other parts ofthe world with cheaper labor, and thegradual imposition of strict environmen-tal regulations on the timber industry.Taken together, these factors have had aprofound impact on Washington’s econo-my, drastically reducing the number ofpeople who work in the timber industryand effectively removing both jobs and away of life that generations of Washing-ton residents considered part of theiridentity. Similar upheavals have takenplace among those who fished for a liv-ing, but advances in that industry havedulled the impact somewhat.

In 1999, Washington’s median householdincome was $45,776 as compared to anational median of $41,994.6 One out of ten residents (10.6 percent) lived belowthe poverty line, as compared to a nation-al average of 12.4 percent. But disparitiesin income across the thirty-nine countiesin Washington are substantial and reflect aconsiderable divide in wealth. Overall percapita income in the state in 1999 was$22,793 (as compared to a national aver-age of $21,587), but per capita income inWashington ranged from a low of$13,534 in Adams County to a high of$30,603 in San Juan County. The countyfigures suggest two patterns of disparity.Only one of the twenty counties to theeast of the Cascades had a median house-hold income that was higher than theoverall median for the state, but five ofthe nineteen counties to the west of theCascades had median household incomeshigher than the state median (and a

6 The analysis in this para-graph is based on data avail-able at two websites:http://factfinder.census.gov/bf/_lang=en_vt_name=DEC_2000_SF3_U_GCTP14_ST2_geo_id=04000US53.html

http://factfinder.census.gov/bf/_lang=en_vt_name=DEC_2000_SF3_U_GCTP14_US9_geo_id=01000US.html

7 If individuals who indicatedthat they were “Hispanic”and “white” are included in the definition ofminority, this percentage rises slightly to 21.2 percent.These calculations are basedupon data available at:http://www.ofm.wa.gov/census2000/sf1/tables/ctable19.htm.

State revenue raising is limited by Initia-tive 601, a citizen referendum passed in1993 that limited the amount that stategovernment can spend from the generalfund and imposed a supermajority votingrequirement on increases in state taxes—two-thirds of the members of bothhouses must approve any measure thatincreases state revenues or results in arevenue-neutral tax shift, and if anyadditional revenues will exceed theformula-based limit put in place by theinitiative, it has to be approved by amajority of the voters.

The combined effect of these factors is to limit the revenues that are available topursue policy of any type. For the artsand culture, this effect is magnified by thedesign and administration of tax exemp-tions. Nonprofit organizations are eligiblefor a narrower range of tax exemptions inthe State of Washington than would likelybe the case elsewhere. Because there is noincome tax, there is no incentive providedby an exemption from income tax, butsuch an exemption is not automaticallybuilt into the sales tax or the business andoccupation tax. Moreover, nonprofitorganizations in Washington (unlike thoseelsewhere) are not automatically eligiblefor certain state tax exemptions or incen-tives by virtue of their federal 501(c)(3)status; rather, they have to apply annuallyfor certain exemptions. The upshot is thatthe benefit of tax exemption is much lesssystematic in Washington than elsewhereand, consequently, it may also be lower.8But, at the same time, the cultural sectorhas been given access to several dedicatedstate taxes and fees, and these work to theadvantage of the sector.

It has been suggested thatbecause the value of being a nonprofit in Washington is lower than elsewhere, the nonprofit sector is less welldeveloped.

Some commentators have posited that the lower value of tax exemptions inWashington has hindered the developmentof nonprofit organizations. Of course, itis hard to know in what direction the

The economy of the state is quiteparticular. It has gone throughcycles of boom and bust becauseof the importance of cyclicalindustries such as naturalresource extraction, aerospace,and information technology.

These cycles have possibly led to a moreuneven development of private supportfor the arts and culture than has been thecase in other places with more stableeconomies. In any event, the ebb andflow of private support is an importantfactor that intersects with state culturalpolicy, particularly in the American frame-work, which relies so heavily on privateinitiative in this sector.

In Washington the governorshipis relatively weak as compared toother states.

The constitution of the State ofWashington was crafted during the pop-ulist movement of the late 1800s, and itwas designed to limit the governor’spower by fragmenting control and placingresponsibility for many state functionssuch as transportation and parks withindependent commissions and panels thatare not under the direct control of thegovernor. Because the governor is consti-tutionally weak relative to other states, heor she plays a weaker role in determiningthe direction of cultural policy.

The tax structure of the state isquite unusual.

Washington is one of seven states that donot have a household income tax and oneof only four states that have no form ofincome tax. Thus, no other state relies soheavily on sales taxes as does Washington.It also levies a gross receipts tax—thebusiness and occupation tax—on busi-nesses and a state property tax in additionto local property taxes. The ratio of statetaxes to local taxes is much higher inWashington than in many states because itfinances a greater proportion of govern-mental services, particularly education (K-12, vocational training, communitycolleges, and state colleges and universi-ties), at the state level. 13

Chapter I: Mapping State Cultural Policy

8 These issues are discussed indetail in Chapter VIII of thisreport.

Map

ping

Sta

te C

ultu

ral P

olic

y: Th

e St

ate

of W

ashi

ngto

n

14

national average of 8.7; but it is in themiddle of this group of comparablestates: Massachusetts has a higher numberof organizations per capita—indeed, avery high number that is nearly twice thenational average—while organizations per capita are approximately 25 percentlower in Indiana and Missouri, and nearly 50 percent lower in Tennessee.

Washington is also higher than the nationalaverage with respect to organizationaldensity by area: 9.2 such organizations per 1,000 square miles as compared to anational average of 6.9; but once again itis in the middle of this group of compa-rable states, higher than Missouri (6.1) orTennessee (7.8) but lower than Indiana(12.9). Massachusetts occupies the longright hand tail of this distribution all byitself with 127.6 arts and cultural organi-zations per 1,000 square miles (even NewYork has only 55.6).

Of course, both the presence and successof nonprofit organizations interact withthe philanthropic habits of the popula-tion. With respect to charitable giving,Washington lags behind other states. In1999 Washington had the sixth highestlevel of adjusted gross income perincome tax return filed, $52,735, but withrespect to average charitable contributionsdeducted per income tax return filed,Washington was fourteenth with an

absence of a tax coupled with the absenceof the corresponding exemption works. Itis true that nonprofit organizations inWashington are not offered a blanketexemption from either the sales and usetax or the business and occupation tax,and it is not clear to what extent nonprof-it organizations actually understand—and therefore take advantage of—theparticular tax exemptions for which theydo qualify. (These issues are discussed fur-ther in Chapter VIII.)

While we were unable to conduct acomplete analysis of the development of nonprofit organizations in Washingtonas compared to elsewhere, we were ableto look at some limited data. IRS Form990 must be filed by many nonprofitorganizations, and nonprofit arts andcultural organizations can be separatedout of the data that these forms generate.What do these data tell us about whetherWashington is more or less endowed withnonprofit arts and cultural organizationsthan other states?

Table I.1 summarizes these data forWashington, for four other states withsimilar populations, and for the UnitedStates as a whole for 1999. Washington ishigher than the national average withrespect to organizational density by popu-lation: 10.4 arts and cultural organizationsper 100,000 residents as compared to a

Table I.1: Density of Arts and Cultural Organizations — Washington Compared to Other States of Similar Size

Arts and Arts andArts and Cultural Cultural

Area Cultural Organizations Organizations Population (square Organizations per 100,000 per 1,000

(2000) miles) (1999) population square miles

Indiana 6,080,485 35,870.18 462 7.6 12.9

Massachusetts 6,349,097 7,837.98 1,000 15.8 127.6

Missouri 5,595,211 68,898.01 418 7.5 6.1

Tennessee 5,689,283 41,219.52 322 5.7 7.8

Washington 5,894,121 66,581.95 614 10.4 9.2

United States 281,421,906 3,536,341.73 24,575 8.7 6.9

Note: This table includes only “reporting public charities” that filed IRS Form 990 and were required to do so. Thefollowing were excluded: foreign organizations, government-associated organizations, and organizations withoutstate identifiers. Organizations not required to report include religious congregations and organizations with lessthan $25,000 in gross receipts.

Source: National Center for Charitable Statistics, State Profiles, http://nccs.urban.org/states.htm.

9 National Center forCharitable Statistics, “Profilesof Individual CharitableContributions by State,1999,” Appendix A(Washington, D.C.: TheUrban Institute, 2001).

10 We are grateful to DonTaylor, revenue analysismanager, Research Division,Washington StateDepartment of Revenue,for this insight. E-mailcorrespondence with theauthors, July 29, 2003.

11 Kelly Barsdate of theNational Assembly of StateArts Agencies characterizesthis situation in WashingtonState as “the exceptionrather than the rule amongstate arts agencies:

“A handful of states arelegally prohibited from giv-ing grant awards to individ-ual artists (Washington,New York Missouri, Texas,and Oklahoma)…. [M]ostof those states have foundother mechanisms—includ-ing regranting or other part-nership mechanisms—tofacilitate the delivery ofartist support. Oklahomaand Missouri are on the listof ‘non-general-operating-support’ states, as well. Soit’s possible that there arealso some legal parameters

Continued on page 16

factor in providing incentives to thecreation of nonprofit organizations.

The referendum process inWashington makes it moredifficult to pursue long-termpolicy initiatives.

Citizen referenda, particularly tax limitreferenda, have a further influence onpolicy. Not only do they limit theresources that are available, they alsoincrease the uncertainty attached to policyplanning for the future. Our intervieweessuggested that in the 1980s there was agood deal more flexibility in state govern-ment. Now the State of Washington ismore tied up because of the effects ofvarious referenda that have been passedby the voters and the threat of new ones.This is seen as reflecting a more generalanti-government attitude, an attitude thatalso would seek to limit the boundaries of state policy.

State agencies can only contractfor services or products; theycannot provide unrestrictedgrants or general operatingsupport.

Article VIII, Section V of the WashingtonState constitution says, “The credit of thestate shall not, in any manner be given orloaned to, or in aid of, any individual,association, company or corporation.”The way in which the Washington StateSupreme Court has interpreted this clausehas led to a set of practices that differsfrom many other states.11 State moneycannot be used for unrestricted grants orfor general operating support. Thus, forexample, the Washington State ArtsCommission cannot give a grant. It has to write contracts for services to be paidon a reimbursement basis. Expenses have to be incurred before they can bereimbursed. This also has the effect ofprohibiting the use of state money forfellowships to individual artists to supporttheir careers; federal money has been usedfor this purpose (and continues to be inthe Folk Arts Program), but state moneycannot be used in this way. WSAC avoidsthis complication by channeling much of

average of $1,024. With respect to thepercentage of gross income devoted todeductible charitable contributions, Wash-ington was in the third lowest quartile ofstates—an average of 1.9 percent ofadjusted gross income was devoted todeductible charitable contributions (wellbelow the national average of 2.1 percent).9

But an important (partial) explanation ofthis difference may lie in the intersectionof American tax reform and the unusualstructure of taxation in WashingtonState.10 The federal Tax Reform Act of1986 had a rather particular effect inWashington. As part of this effort at tax reform, Congress disallowed thededuction of retail sales taxes for house-holds that itemize their federal income tax deductions, while continuing to allowthe itemization of state personal incometaxes. Because Washington relies veryheavily on the sales tax—the highestdegree of reliance in the country—andbecause Washington has no income tax,the result of this change in the TaxReform Act was that many fewer upperincome households in Washington foundit advantageous to itemize their deduc-tions on their federal income tax forms;they now simply take the standard deduc-tion. Since charitable contributions arealso one of the expenditures that qualifyfor itemization, the federal incentive for asignificant proportion of Washington resi-dents to make such (deductible) contribu-tions simply disappeared.

A fuller inquiry into the relative supply ofnonprofit organizations and their supportwould have to consider a number ofother factors not directly linked to thepresence or generosity of tax incentives:the fact that smaller organizations do notshow up in the Form 990 data, the factthat there are other organizations that wewould consider to be “cultural” that arenot categorized in the Form 990 data as“arts and culture,” the fact that nonprofitorganizations are likely to be older, onaverage, in eastern states than in westernstates and have therefore had greateropportunity to develop, and the fact thatdirect government aid may also be a 15

Chapter I: Mapping State Cultural Policy

Map

ping

Sta

te C

ultu

ral P

olic

y: Th

e St

ate

of W

ashi

ngto

n

16

Republicans were the cultural progressivesand the Democrats were the culturalconservatives. This is less true today. Butthe result is that it is not only difficult topredict the Legislature’s commitment tocultural policy, it is also difficult to predictan individual legislator’s commitment byhis or her political affiliation. In the endthis commitment among Washington’slegislators has more to do with personalexperience than with partisan politics.Generally it has been easier to gain sup-port for heritage policy than for artspolicy or humanities policy as legislatorsfind showcasing the history of the statean attractive thing to support. Yet, manyof the individuals whom we interviewedexpressed the concern that the number of legislators committed to cultural policyis dwindling.

On MethodologyThough extensive, our methodology has not been particularly complicated.Nevertheless, a few remarks are in order.Our data come from four sources: inter-views, legislation, policy and programdocuments, and budgets.

We conducted approximately one hundredand seventy interviews in two phases. (Alist of the interviews that we conducted iscontained in the Appendices.) The firstphase focused on individuals who wereparticularly knowledgeable about statecultural policy. Most of these were staffof state agencies, but we also interviewedjournalists who cover the arts and culture,state legislators, and other individualswhom we had reason to believe wereparticularly knowledgeable about one oranother aspect of state cultural policy.The second phase was to have been focusedon targets of state cultural policy—offices, organizations, and individualswhose behavior was to be shaped bycultural policy in one way or another—and we were able to interview many suchindividuals, but as our inquiries led tomore and more pockets of cultural policyin state agencies we found that we had toexpand our first round of interviews toinclude these as well.

its direct support to artists through ArtistTrust, an independent, private, nonprofitorganization.

Whether this is a good or bad thingdepends upon with whom you speak.On the one hand, there is greateraccountability in the support system—taxpayer money is less likely to find itsway into dark holes—and recipientorganizations know that they have to haveother sources of income in order tomanage their cash flow. To some thisseems appropriate, providing a test ofbroader support, but to others this seemsunnecessarily bureaucratic, ignoring thefact that many cultural organizations aresmall and without the substantialresources that would allow them to paytheir bills up front while waiting forreimbursement.

There is one way in which WashingtonState may be more typical of manyAmerican states, but this attribute mayhave unforeseen implications for cultural policy:

Politically, the state is quitepolarized. Both the House andthe Senate are basically splitalong party lines, making it diffi-cult to move in any particularpolicy direction.

Many American states have split legislativecontrol, often with a relatively even splitacross both houses between Democratsand Republicans, and many have a gover-nor who is of a different party than themajority of its legislators. In such a cir-cumstance, the Legislature tends not toprovide a strong or clear policy direction.Legislators may tend to be risk adverseand unwilling to go out on a limb.

In Washington, this balance is, to a largedegree, reflective of geography: Republi-cans tend to come from the eastern partof the state and Democrats from thewest, with Republican legislators now also being elected from the suburbs in the west. Interestingly, within the memoryof most adults, particularly during theadministration of Governor Daniel Evans(1965-1977), Washington’s moderate

Continued from page 15

shaping their decisions about both kinds of grantfunding…. New Mexico isconstitutionally prohibited fromusing the term general operat-ing support, but they have been resourceful and found amechanism that essentiallyaccomplishes the same thingunder a different name…. Butagain, this is rare. There areonly a few states…that don’taward operating support ofsome form or another. Thosechoices are not necessarilyabout state legal restrictions,but…about how the agencydecides its thin resources canbe used most strategically.Depending on your state’sneeds and environment, generaloperating support may or maynot be part of the answer tothe question, Where can ourdollars have the greatest impactand critical mass? Maine is theclassic example here…. And afinal wrinkle… some otherstates may have legal restric-tions pertaining to theirexpenditure of state funds toindividuals (artists). There maybe states that are happily com-plying with those mandates by using federal funding (orsome other financial source) to support their artists andoperating awards.”

E-mail correspondence withthe authors, October 7, 2002.

There are two aspects of our interviews,however, that need to be kept in mind.We have wondered from time to time ifwe were getting mostly positive spin inour interviews. At least one intervieweedrew this distinction explicitly, telling usthat she would tell us only what she couldsay. It is only natural that intervieweeswish to put their (and their agency’s) bestfoot forward. Where possible we tried totriangulate on what we were hearing, ask-ing the same or related questions to avariety of individuals. Often, we receivedrather candid responses. We would like tothink that our status as “outsiders” withno local political agenda allowed ourinterviewees to interact with us moreopenly. When we completed a full draft ofthis report, we sent it to twenty of the keyindividuals whom we had interviewed aswell as to our project advisory board,and the comments we received and therevisions we made provided anotherround of such triangulation.